Brain Changes Associated with Chronic Pain

Pain is the human body’s natural response to injury or illness, and it is often a warning that something is wrong. Once the problem is healed, we generally stop experiencing this painful symptoms, however, what happens when the pain continues long after the cause is gone? Chronic pain is medically defined as persistent pain that lasts 3 to 6 months or more. Chronic pain is certainly a challenging condition to live with, affecting everything from the individual’s activity levels and their ability to work as well as their personal relationships and psychological conditions. But, are you aware that chronic pain may also be affecting the structure and function of your brain? It turns out these brain changes may lead to both cognitive and psychological impairment.

Chronic pain doesn’t just influence a singular region of the mind, as a matter of fact, it can result in changes to numerous essential areas of the brain, most of which are involved in many fundamental processes and functions. Various research studies over the years have found alterations to the hippocampus, along with reduction in grey matter from the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, amygdala, brainstem and right insular cortex, to name a few, associated with chronic pain. A breakdown of a few of the structure of these regions and their related functions might help to put these brain changes into context, for a lot of individuals with chronic pain. The purpose of the following article is to demonstrate as well as discuss the structural and functional brain changes associated with chronic pain, particularly in the case where those reflect probably neither damage nor atrophy.

Structural Brain Changes in Chronic Pain Reflect Probably Neither Damage Nor Atrophy

Abstract

Chronic pain appears to be associated with brain gray matter reduction in areas ascribable to the transmission of pain. The morphological processes underlying these structural changes, probably following functional reorganisation and central plasticity in the brain, remain unclear. The pain in hip osteoarthritis is one of the few chronic pain syndromes which are principally curable. We investigated 20 patients with chronic pain due to unilateral coxarthrosis (mean age 63.25�9.46 (SD) years, 10 female) before hip joint endoprosthetic surgery (pain state) and monitored brain structural changes up to 1 year after surgery: 6�8 weeks, 12�18 weeks and 10�14 month when completely pain free. Patients with chronic pain due to unilateral coxarthrosis had significantly less gray matter compared to controls in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), insular cortex and operculum, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and orbitofrontal cortex. These regions function as multi-integrative structures during the experience and the anticipation of pain. When the patients were pain free after recovery from endoprosthetic surgery, a gray matter increase in nearly the same areas was found. We also found a progressive increase of brain gray matter in the premotor cortex and the supplementary motor area (SMA). We conclude that gray matter abnormalities in chronic pain are not the cause, but secondary to the disease and are at least in part due to changes in motor function and bodily integration.

Introduction

Evidence of functional and structural reorganization in chronic pain patients support the idea that chronic pain should not only be conceptualized as an altered functional state, but also as a consequence of functional and structural brain plasticity [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6]. In the last six years, more than 20 studies were published demonstrating structural brain changes in 14 chronic pain syndromes. A striking feature of all of these studies is the fact that the gray matter changes were not randomly distributed, but occur in defined and functionally highly specific brain areas � namely, involvement in supraspinal nociceptive processing. The most prominent findings were different for each pain syndrome, but overlapped in the cingulate cortex, the orbitofrontal cortex, the insula and dorsal pons [4]. Further structures comprise the thalamus, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, basal ganglia and hippocampal area. These findings are often discussed as cellular atrophy, reinforcing the idea of damage or loss of brain gray matter [7], [8], [9]. In fact, researchers found a correlation between brain gray matter decreases and duration of pain [6], [10]. But the duration of pain is also linked to the patient�s age, and the age dependent global, but also regionally specific decline of gray matter is well documented [11]. On the other hand, these structural changes could also be a decrease in cell size, extracellular fluids, synaptogenesis, angiogenesis or even due to blood volume changes [4], [12], [13]. Whatever the source is, for our interpretation of such findings it is important to see these morphometric findings in the light of a wealth of morphometric studies in exercise dependant plasticity, given that regionally specific structural brain changes have been repeatedly shown following cognitive and physical exercise [14].

It is not understood why only a relatively small proportion of humans develop a chronic pain syndrome, considering that pain is a universal experience. The question arises whether in some humans a structural difference in central pain transmitting systems may act as a diathesis for chronic pain. Gray matter changes in phantom pain due to amputation [15] and spinal cord injury [3] indicate that the morphological changes of the brain are, at least in part, a consequence of chronic pain. However, the pain in hip osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the few chronic pain syndrome which is principally curable, as 88% of these patients are regularly free of pain following total hip replacement (THR) surgery [16]. In a pilot study we have analysed ten patients with hip OA before and shortly after surgery. We found decreases of gray matter in the anterior cingulated cortex (ACC) and insula during chronic pain before THR surgery and found increases of gray matter in the corresponding brain areas in the pain free condition after surgery [17]. Focussing on this result, we now expanded our studies investigating more patients (n?=?20) after successful THR and monitored structural brain changes in four time intervals, up to one year following surgery. To control for gray matter changes due to motor improvement or depression we also administered questionnaires targeting improvement of motor function and mental health.

Materials and Methods

Volunteers

The patients reported here are a subgroup of 20 patients out of 32 patients published recently who were compared to an age- and gender-matched healthy control group [17] but participated in an additional one year follow-up investigation. After surgery 12 patients dropped out because of a second endoprosthetic surgery (n?=?2), severe illness (n?=?2) and withdrawal of consent (n?=?8). This left a group of twenty patients with unilateral primary hip OA (mean age 63.25�9.46 (SD) years, 10 female) who were investigated four times: before surgery (pain state) and again 6�8 and 12�18 weeks and 10�14 months after endoprosthetic surgery, when completely pain free. All patients with primary hip OA had a pain history longer than 12 months, ranging from 1 to 33 years (mean 7.35 years) and a mean pain score of 65.5 (ranging from 40 to 90) on a visual analogue scale (VAS) ranging from 0 (no pain) to 100 (worst imaginable pain). We assessed any occurrence of minor pain events, including tooth-, ear- and headache up to 4 weeks prior to the study. We also randomly selected the data from 20 sex- and age matched healthy controls (mean age 60,95�8,52 (SD) years, 10 female) of the 32 of the above mentioned pilot study [17]. None of the 20 patients or of the 20 sex- and age matched healthy volunteers had any neurological or internal medical history. The study was given ethical approval by the local Ethics committee and written informed consent was obtained from all study participants prior to examination.

Behavioural Data

We collected data on depression, somatization, anxiety, pain and physical and mental health in all patients and all four time points using the following standardized questionnaires: Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [18], Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) [19], Schmerzempfindungs-Skala (SES?=?pain unpleasantness scale) [20] and Health Survey 36-Item Short Form (SF-36) [21] and the Nottingham Health Profile (NHP). We conducted repeated measures ANOVA and paired two-tailed t-Tests to analyse the longitudinal behavioural data using SPSS 13.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), and used Greenhouse Geisser correction if the assumption for sphericity was violated. The significance level was set at p<0.05.

VBM – Data Acquisition

Image acquisition. High-resolution MR scanning was performed on a 3T MRI system (Siemens Trio) with a standard 12-channel head coil. For each of the four time points, scan I (between 1 day and 3 month before endoprosthetic surgery), scan II (6 to 8 weeks after surgery), scan III (12 to 18 weeks after surgery) and scan IV (10�14 months after surgery), a T1 weighted structural MRI was acquired for each patient using a 3D-FLASH sequence (TR 15 ms, TE 4.9 ms, flip angle 25�, 1 mm slices, FOV 256�256, voxel size 1�1�1 mm).

Image Processing and Statistical Analysis

Data pre-processing and analysis were performed with SPM2 (Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London, UK) running under Matlab (Mathworks, Sherborn, MA, USA) and containing a voxel-based morphometry (VBM)-toolbox for longitudinal data, that is based on high resolution structural 3D MR images and allows for applying voxel-wise statistics to detect regional differences in gray matter density or volumes [22], [23]. In summary, pre-processing involved spatial normalization, gray matter segmentation and 10 mm spatial smoothing with a Gaussian kernel. For the pre-processing steps, we used an optimized protocol [22], [23] and a scanner- and study-specific gray matter template [17]. We used SPM2 rather than SPM5 or SPM8 to make this analysis comparable to our pilot study [17]. as it allows an excellent normalisation and segmentation of longitudinal data. However, as a more recent update of VBM (VBM8) became available recently (http://dbm.neuro.uni-jena.de/vbm/), we also used VBM8.

Cross-Sectional Analysis

We used a two-sample t-test in order to detect regional differences in brain gray matter between groups (patients at time point scan I (chronic pain) and healthy controls). We applied a threshold of p<0.001 (uncorrected) across the whole brain because of our strong a priory hypothesis, which is based on 9 independent studies and cohorts showing decreases in gray matter in chronic pain patients [7], [8], [9], [15], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], that gray matter increases will appear in the same (for pain processing relevant) regions as in our pilot study (17). The groups were matched for age and sex with no significant differences between the groups. To investigate whether the differences between groups changed after one year, we also compared patients at time point scan IV (pain free, one year follow-up) to our healthy control group.

Longitudinal Analysis

To detect differences between time points (Scan I�IV) we compared the scans before surgery (pain state) and again 6�8 and 12�18 weeks and 10�14 months after endoprosthetic surgery (pain free) as repeated measure ANOVA. Because any brain changes due to chronic pain may need some time to recede following operation and cessation of pain and because of the post surgery pain the patients reported, we compared in the longitudinal analysis scan I and II with scan III and IV. For detecting changes that are not closely linked to pain, we also looked for progressive changes over all time intervals. We flipped the brains of patients with OA of the left hip (n?=?7) in order to normalize for the side of the pain for both, the group comparison and the longitudinal analysis, but primarily analysed the unflipped data. We used the BDI score as a covariate in the model.

Results

Behavioral Data

All patients reported chronic hip pain before surgery and were pain free (regarding this chronic pain) immediately after surgery, but reported rather acute post-surgery pain on scan II which was different from the pain due to osteoarthritis. The mental health score of the SF-36 (F(1.925/17.322)?=?0.352, p?=?0.7) and the BSI global score GSI (F(1.706/27.302)?=?3.189, p?=?0.064) showed no changes over the time course and no mental co-morbidity. None of the controls reported any acute or chronic pain and none showed any symptoms of depression or physical/mental disability.

Before surgery, some patients showed mild to moderate depressive symptoms in BDI scores that significantly decreased on scan III (t(17)?=?2.317, p?=?0.033) and IV (t(16)?=?2.132, p?=?0.049). Additionally, the SES scores (pain unpleasantness) of all patients improved significantly from scan I (before the surgery) to scan II (t(16)?=?4.676, p<0.001), scan III (t(14)?=?4.760, p<0.001) and scan IV (t(14)?=?4.981, p<0.001, 1 year after surgery) as pain unpleasantness decreased with pain intensity. The pain rating on scan 1 and 2 were positive, the same rating on day 3 and 4 negative. The SES only describes the quality of perceived pain. It was therefore positive on day 1 and 2 (mean 19.6 on day 1 and 13.5 on day 2) and negative (n.a.) on day 3 & 4. However, some patients did not understand this procedure and used the SES as a global �quality of life� measure. This is why all patients were asked on the same day individually and by the same person regarding pain occurrence.

In the short form health survey (SF-36), which consists of the summary measures of a Physical Health Score and a Mental Health Score [29], the patients improved significantly in the Physical Health score from scan I to scan II (t(17)?=??4.266, p?=?0.001), scan III (t(16)?=??8.584, p<0.001) and IV (t(12)?=??7.148, p<0.001), but not in the Mental Health Score. The results of the NHP were similar, in the subscale �pain� (reversed polarity) we observed a significant change from scan I to scan II (t(14)?=??5.674, p<0.001, scan III (t(12)?=??7.040, p<0.001 and scan IV (t(10)?=??3.258, p?=?0.009). We also found a significant increase in the subscale �physical mobility� from scan I to scan III (t(12)?=??3.974, p?=?0.002) and scan IV (t(10)?=??2.511, p?=?0.031). There was no significant change between scan I and scan II (six weeks after surgery).

Structural Data

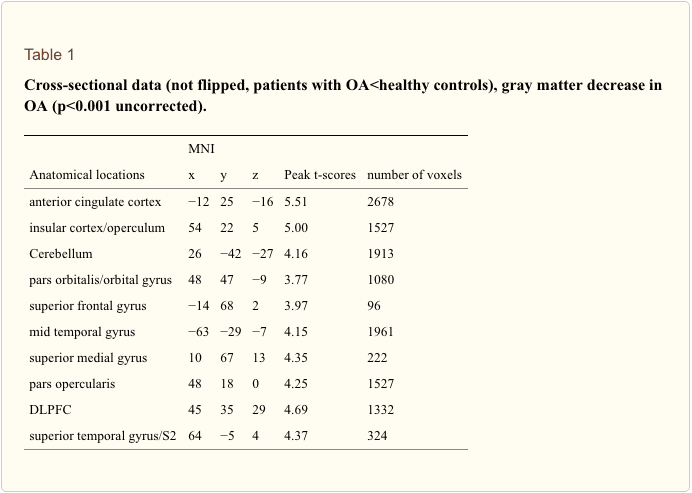

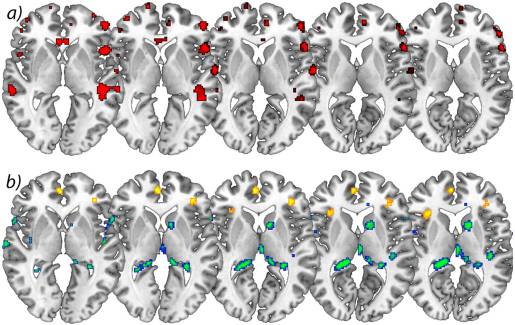

Cross-sectional analysis. We included age as a covariate in the general linear model and found no age confounds. Compared to sex and age matched controls, patients with primary hip OA (n?=?20) showed pre-operatively (Scan I) reduced gray matter in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), the insular cortex, operculum, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), right temporal pole and cerebellum (Table 1 and Figure 1). Except for the right putamen (x?=?31, y?=??14, z?=??1; p<0.001, t?=?3.32) no significant increase in gray matter density was found in patients with OA compared to healthy controls. Comparing patients at time point scan IV with matched controls, the same results were found as in the cross-sectional analysis using scan I compared to controls.

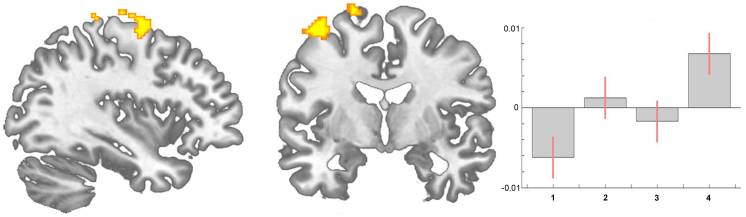

Figure 1: Statistical parametric maps demonstrating the structural differences in gray matter in patients with chronic pain due to primary hip OA compared to controls and longitudinally compared to themselves over time. Significant gray matter changes are shown superimposed in color, cross-sectional data is depicted in red and longitudinal data in yellow. Axial plane: the left side of the picture is the left side of the brain. top: Areas of significant decrease of gray matter between patients with chronic pain due to primary hip OA and unaffected control subjects. p<0.001 uncorrected bottom: Gray matter increase in 20 pain free patients at the third and fourth scanning period after total hip replacement surgery, as compared to the first (preoperative) and second (6�8 weeks post surgery) scan. p<0.001 uncorrected Plots: Contrast estimates and 90% Confidence interval, effects of interest, arbitrary units. x-axis: contrasts for the 4 timepoints, y-axis: contrast estimate at ?3, 50, 2 for ACC and contrast estimate at 36, 39, 3 for insula.

Flipping the data of patients with left hip OA (n?=?7) and comparing them with healthy controls did not change the results significantly, but for a decrease in the thalamus (x?=?10, y?=??20, z?=?3, p<0.001, t?=?3.44) and an increase in the right cerebellum (x?=?25, y?=??37, z?=??50, p<0.001, t?=?5.12) that did not reach significance in the unflipped data of the patients compared to controls.

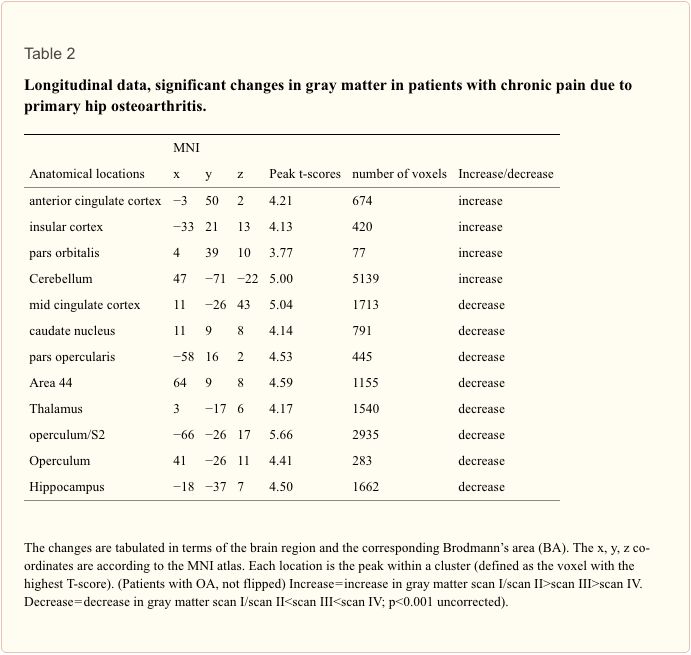

Longitudinal analysis. In the longitudinal analysis, a significant increase (p<.001 uncorrected) of gray matter was detected by comparing the first and second scan (chronic pain/post-surgery pain) with the third and fourth scan (pain free) in the ACC, insular cortex, cerebellum and pars orbitalis in the patients with OA (Table 2 and Figure 1). Gray matter decreased over time (p<.001 whole brain analysis uncorrected) in the secondary somatosensory cortex, hippocampus, midcingulate cortex, thalamus and caudate nucleus in patients with OA (Figure 2).

Figure 2: a) Significant increases in brain gray matter following successful operation. Axial view of significant decrease of gray matter in patients with chronic pain due to primary hip OA compared to control subjects. p<0.001 uncorrected (cross-sectional analysis), b) Longitudinal increase of gray matter over time in yellow comparing scan I&IIscan III>scan IV) in patients with OA. p<0.001 uncorrected (longitudinal analysis). The left side of the picture is the left side of the brain.

Flipping the data of patients with left hip OA (n?=?7) did not change the results significantly, but for a decrease of brain gray matter in the Heschl�s Gyrus (x?=??41, y?=??21, z?=?10, p<0.001, t?=?3.69) and Precuneus (x?=?15, y?=??36, z?=?3, p<0.001, t?=?4.60).

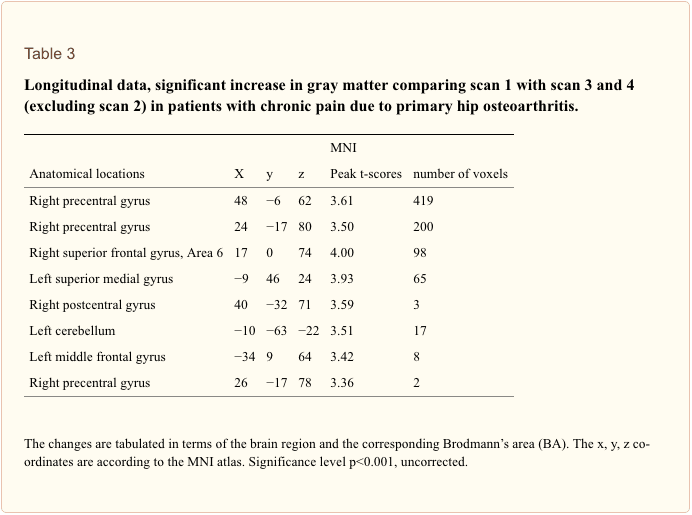

By contrasting the first scan (presurgery) with scans 3+4 (postsurgery), we found an increase of gray matter in the frontal cortex and motor cortex (p<0.001 uncorrected). We note that this contrast is less stringent as we have now less scans per condition (pain vs. non-pain). When we lower the threshold we repeat what we have found using contrast of 1+2 vs. 3+4.

By looking for areas that increase over all time intervals, we found changes of brain gray matter in motor areas (area 6) in patients with coxarthrosis following total hip replacement (scan I<scan II<scan III<scan IV)). Adding the BDI scores as a covariate did not change the results. Using the recently available software tool VBM8 including DARTEL normalisation (http://dbm.neuro.uni-jena.de/vbm/) we could replicate this finding in the anterior and mid-cingulate cortex and both anterior insulae.

We calculated the effect sizes and the cross-sectional analysis (patients vs. controls) yielded a Cohen�s d of 1.78751 in the peak voxel of the ACC (x?=??12, y?=?25, z?=??16). We also calculated Cohen�s d for the longitudinal analysis (contrasting scan 1+2 vs. scan 3+4). This resulted in a Cohen�s d of 1.1158 in the ACC (x?=??3, y?=?50, z?=?2). Regarding the insula (x?=??33, y?=?21, z?=?13) and related to the same contrast, Cohen�s d is 1.0949. Additionally, we calculated the mean of the non-zero voxel values of the Cohen�s d map within the ROI (comprised of the anterior division of the cingulate gyrus and the subcallosal cortex, derived from the Harvard-Oxford Cortical Structural Atlas): 1.251223.

Dr. Alex Jimenez’s Insight

Chronic pain patients can experience a variety of health issues over time, aside from their already debilitating symptoms. For instance, many individuals will experience sleeping problems as a result of their pain, but most importantly, chronic pain can lead to various mental health issues as well, including anxiety and depression. The effects that pain can have on the brain may seem all too overwhelming but growing evidence suggests that these brain changes are not permanent and can be reversed when chronic pain patients receive the proper treatment for their underlying health issues. According to the article, gray matter abnormalities found in chronic pain do not reflect brain damage, but rather, they are a reversible consequence which normalizes when the pain is adequately treated. Fortunately, a variety of treatment approaches are available to help ease chronic pain symptoms and restore the structure and function of the brain.

Discussion

Monitoring whole brain structure over time, we confirm and expand our pilot data published recently [17]. We found changes in brain gray matter in patients with primary hip osteoarthritis in the chronic pain state, which reverse partly when these patients are pain free, following hip joint endoprosthetic surgery. The partial increase in gray matter after surgery is nearly in the same areas where a decrease of gray matter has been seen before surgery. Flipping the data of patients with left hip OA (and therefore normalizing for the side of the pain) had only little impact on the results but additionally showed a decrease of gray matter in the Heschl�s gyrus and Precuneus that we cannot easily explain and, as no a priori hypothesis exists, regard with great caution. However, the difference seen between patients and healthy controls at scan I was still observable in the cross-sectional analysis at scan IV. The relative increase of gray matter over time is therefore subtle, i.e. not sufficiently distinct to have an effect on the cross sectional analysis, a finding that has already been shown in studies investigating experience dependant plasticity [30], [31]. We note that the fact that we show some parts of brain-changes due to chronic pain to be reversible does not exclude that some other parts of these changes are irreversible.

Interestingly, we observed that the gray matter decrease in the ACC in chronic pain patients before surgery seems to continue 6 weeks after surgery (scan II) and only increases towards scan III and IV, possibly due to post-surgery pain, or decrease in motor function. This is in line with the behavioural data of the physical mobility score included in the NHP, which post-operatively did not show any significant change at time point II but significantly increased towards scan III and IV. Of note, our patients reported no pain in the hip after surgery, but experienced post-surgery pain in surrounding muscles and skin which was perceived very differently by patients. However, as patients still reported some pain at scan II, we also contrasted the first scan (pre-surgery) with scans III+IV (post-surgery), revealing an increase of gray matter in the frontal cortex and motor cortex. We note that this contrast is less stringent because of less scans per condition (pain vs. non-pain). When we lowered the threshold we repeat what we have found using contrast of I+II vs. III+IV.

Our data strongly suggest that gray matter alterations in chronic pain patients, which are usually found in areas involved in supraspinal nociceptive processing [4] are neither due to neuronal atrophy nor brain damage. The fact that these changes seen in the chronic pain state do not reverse completely could be explained with the relatively short period of observation (one year after operation versus a mean of seven years of chronic pain before the operation). Neuroplastic brain changes that may have developed over several years (as a consequence of constant nociceptive input) need probably more time to reverse completely. Another possibility why the increase of gray matter can only be detected in the longitudinal data but not in the cross-sectional data (i.e. between cohorts at time point IV) is that the number of patients (n?=?20) is too small. It needs to be pointed out that the variance between brains of several individuals is quite large and that longitudinal data have the advantage that the variance is relatively small as the same brains are scanned several times. Consequently, subtle changes will only be detectable in longitudinal data [30], [31], [32]. Of course we cannot exclude that these changes are at least partly irreversible although that is unlikely, given the findings of exercise specific structural plasticity and reorganisation [4], [12], [30], [33], [34]. To answer this question, future studies need to investigate patients repeatedly over longer time frames, possibly years.

We note that we can only make limited conclusions regarding the dynamics of morphological brain changes over time. The reason is that when we designed this study in 2007 and scanned in 2008 and 2009, it was not known whether structural changes would occur at all and for reasons of feasibility we chose the scan dates and time frames as described here. One could argue that the gray matter changes in time, which we describe for the patient group, might have happened in the control group as well (time effect). However, any changes due to aging, if at all, would be expected to be a decrease in volume. Given our a priori hypothesis, based on 9 independent studies and cohorts showing decreases in gray matter in chronic pain patients [7], [8], [9], [15], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], we focussed on regional increases over time and therefore believe our finding not to be a simple time effect. Of note, we cannot rule out that the gray matter decrease over time that we found in our patient group could be due to a time effect, as we have not scanned our control group in the same time frame. Given the findings, future studies should aim at more and shorter time intervals, given that exercise dependant morphometric brain changes may occur as fast as after 1 week [32], [33].

In addition to the impact of the nociceptive aspect of pain on brain gray matter [17], [34] we observed that changes in motor function probably also contribute to the structural changes. We found motor and premotor areas (area 6) to increase over all time intervals (Figure 3). Intuitively this may be due to improvement of motor function over time as the patients were no more restricted in living a normal life. Notably we did not focus on motor function but an improvement in pain experience, given our original quest to investigate whether the well-known reduction in brain gray matter in chronic pain patients is in principle reversible. Consequently, we did not use specific instruments to investigate motor function. Nevertheless, (functional) motor cortex reorganization in patients with pain syndromes is well documented [35], [36], [37], [38]. Moreover, the motor cortex is one target in therapeutic approaches in medically intractable chronic pain patients using direct brain stimulation [39], [40], transcranial direct current stimulation [41], and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation [42], [43]. The exact mechanisms of such modulation (facilitation vs. inhibition, or simply interference in the pain-related networks) are not yet elucidated [40]. A recent study demonstrated that a specific motor experience can alter the structure of the brain [13]. Synaptogenesis, reorganisation of movement representations and angiogenesis in motor cortex may occur with special demands of a motor task. Tsao et al. showed reorganisation in the motor cortex of patients with chronic low back pain that seem to be back pain-specific [44] and Puri et al. observed a reduction in left supplemental motor area gray matter in fibromyalgia sufferers [45]. Our study was not designed to disentangle the different factors that may change the brain in chronic pain but we interpret our data concerning the gray matter changes that they do not exclusively mirror the consequences of constant nociceptive input. In fact, a recent study in neuropathic pain patients pointed out abnormalities in brain regions that encompass emotional, autonomic, and pain perception, implying that they play a critical role in the global clinical picture of chronic pain [28].

Figure 3: Statistical parametric maps demonstrating a significant increase of brain gray matter in motor areas (area 6) in patients with coxarthrosis before compared to after THR (longitudinal analysis, scan I<scan II<scan III<scan IV). Contrast estimates at x?=?19, y?=??12, z?=?70.

Two recent pilot studies focussed on hip replacement therapy in osteoarthritis patients, the only chronic pain syndrome which is principally curable with total hip replacement [17], [46] and these data are flanked by a very recent study in chronic low back pain patients [47]. These studies need to be seen in the light of several longitudinal studies investigating experience-dependent neuronal plasticity in humans on a structural level [30], [31] and a recent study on structural brain changes in healthy volunteers experiencing repeated painful stimulation [34]. The key message of all these studies is that the main difference in the brain structure between pain patients and controls may recede when the pain is cured. However, it must be taken into account that it is simply not clear whether the changes in chronic pain patients are solely due to nociceptive input or due to the consequences of pain or both. It is more than likely that behavioural changes, such as deprivation or enhancement of social contacts, agility, physical training and life style changes are sufficient to shape the brain [6], [12], [28], [48]. Particularly depression as a co-morbidity or consequence of pain is a key candidate to explain the differences between patients and controls. A small group of our patients with OA showed mild to moderate depressive symptoms that changed with time. We did not find the structural alterations to covary significantly with the BDI-score but the question arises how many other behavioural changes due to the absence of pain and motor improvement may contribute to the results and to what extent they do. These behavioural changes can possibly influence a gray matter decrease in chronic pain as well as a gray matter increase when pain is gone.

Another important factor which may bias our interpretation of the results is the fact that nearly all patients with chronic pain took medications against pain, which they stopped when they were pain free. One could argue that NSAIDs such as diclofenac or ibuprofen have some effects on neural systems and the same holds true for opioids, antiepileptics and antidepressants, medications which are frequently used in chronic pain therapy. The impact of pain killers and other medications on morphometric findings may well be important (48). No study so far has shown effects of pain medication on brain morphology but several papers found that changes in brain structure in chronic pain patients are neither solely explained by pain related inactivity [15], nor by pain medication [7], [9], [49]. However, specific studies are lacking. Further research should focus the experience-dependent changes in cortical plasticity, which may have vast clinical implications for the treatment of chronic pain.

We also found decreases of gray matter in the longitudinal analysis, possibly due to reorganisation processes that accompany changes in motor function and pain perception. There is little information available about longitudinal changes in brain gray matter in pain conditions, for this reason we have no hypothesis for a gray matter decrease in these areas after the operation. Teutsch et al. [25] found an increase of brain gray matter in the somatosensory and midcingulate cortex in healthy volunteers that experienced painful stimulation in a daily protocol for eight consecutive days. The finding of gray matter increase following experimental nociceptive input overlapped anatomically to some degree with the decrease of brain gray matter in this study in patients that were cured of long-lasting chronic pain. This implies that nociceptive input in healthy volunteers leads to exercise dependant structural changes, as it possibly does in patients with chronic pain, and that these changes reverse in healthy volunteers when nociceptive input stops. Consequently, the decrease of gray matter in these areas seen in patients with OA could be interpreted to follow the same fundamental process: exercise dependant changes brain changes [50]. As a non-invasive procedure, MR Morphometry is the ideal tool for the quest to find the morphological substrates of diseases, deepening our understanding of the relationship between brain structure and function, and even to monitor therapeutic interventions. One of the great challenges in the future is to adapt this powerful tool for multicentre and therapeutic trials of chronic pain.

Limitations of this Study

Although this study is an extension of our previous study expanding the follow-up data to 12 months and investigating more patients, our principle finding that morphometric brain changes in chronic pain are reversible is rather subtle. The effect sizes are small (see above) and the effects are partly driven by a further reduction of regional brain gray matter volume at the time-point of scan 2. When we exclude the data from scan 2 (directly after the operation) only significant increases in brain gray matter for motor cortex and frontal cortex survive a threshold of p<0.001 uncorrected (Table 3).

Conclusion

It is not possible to distinguish to what extent the structural alterations we observed are due to changes in nociceptive input, changes in motor function or medication consumption or changes in well-being as such. Masking the group contrasts of the first and last scan with each other revealed much less differences than expected. Presumably, brain alterations due to chronic pain with all consequences are developing over quite a long time course and may also need some time to revert. Nevertheless, these results reveal processes of reorganisation, strongly suggesting that chronic nociceptive input and motor impairment in these patients leads to altered processing in cortical regions and consequently structural brain changes which are in principle reversible.

Acknowledgments

We thank all volunteers for the participation in this study and the Physics and Methods group at NeuroImage Nord in Hamburg. The study was given ethical approval by the local Ethics committee and written informed consent was obtained from all study participants prior to examination.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by grants from the DFG (German Research Foundation) (MA 1862/2-3) and BMBF (The Federal Ministry of Education and Research) (371 57 01 and NeuroImage Nord). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

The Endocannabinoid System: The Essential System You�ve Never Heard Of

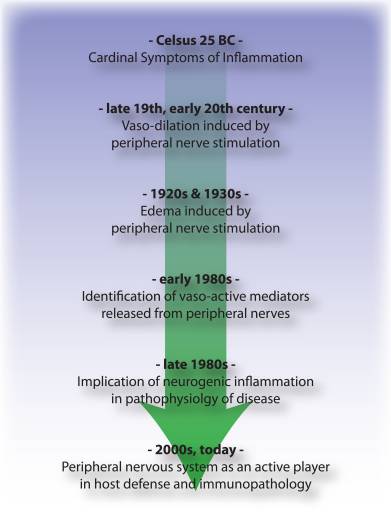

In case you haven’t heard of the endocannabinoid system, or ECS, there’s no need to feel embarrassed. Back in the 1960’s, the investigators that became interested in the bioactivity of Cannabis eventually isolated many of its active chemicals. It took another 30 years, however, for researchers studying animal models to find a receptor for these ECS chemicals in the brains of rodents, a discovery which opened a whole world of inquiry into the ECS receptors existence and what their physiological purpose is.

We now know that most animals, from fish to birds to mammals, possess an endocannabinoid, and we know that humans not only make their own cannabinoids that interact with this particular system, but we also produce other compounds that interact with the ECS, those of which are observed in many different plants and foods, well beyond the Cannabis species.

As a system of the human body, the ECS isn’t an isolated structural platform like the nervous system or cardiovascular system. Instead, the ECS is a set of receptors widely distributed throughout the body which are activated through a set of ligands we collectively know as endocannabinoids, or endogenous cannabinoids. Both verified receptors are just called CB1 and CB2, although there are others which were proposed. PPAR and TRP channels also mediate some functions. Likewise, you will find just two well-documented endocannabinoids: anadamide and 2-arachidonoyl glycerol, or 2-AG.

Moreover, fundamental to the endocannabinoid system are the enzymes that synthesize and break down the endocannabinoids. Endocannabinoids are believed to be synthesized in an as-needed foundation. The primary enzymes involved are diacylglycerol lipase and N-acyl-phosphatidylethanolamine-phospholipase D, which respectively synthesize 2-AG and anandamide. The two main degrading enzymes are fatty acid amide hydrolase, or FAAH, which breaks down anandamide, and monoacylglycerol lipase, or MAGL, which breaks down 2-AG. The regulation of these two enzymes may increase or decrease the modulation of the ECS.

What is the Function of the ECS?

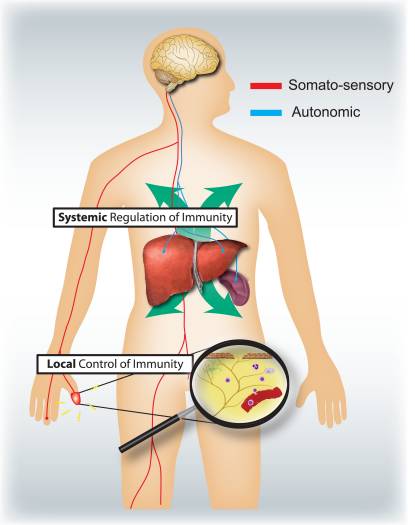

The ECS is the principal homeostatic regulatory system of the body. It may readily be viewed as the body’s internal adaptogenic system, always working to maintain the balance of a variety of function. Endocannabinoids broadly work as neuromodulators and, as such, they regulate a broad range of bodily processes, from fertility to pain. Some of those better-known functions from the ECS are as follows:

Nervous System

From the central nervous system, or the CNS, general stimulation of the CB1 receptors will inhibit the release of glutamate and GABA. In the CNS, the ECS plays a role in memory formation and learning, promotes neurogenesis in the hippocampus, also regulates neuronal excitability. The ECS also plays a part in the way the brain will react to injury and inflammation. From the spinal cord, the ECS modulates pain signaling and boosts natural analgesia. In the peripheral nervous system, in which CB2 receptors control, the ECS acts primarily in the sympathetic nervous system to regulate functions of the intestinal, urinary, and reproductive tracts.

Stress and Mood

The ECS has multiple impacts on stress reactions and emotional regulation, such as initiation of this bodily response to acute stress and adaptation over time to more long-term emotions, such as fear and anxiety. A healthy working endocannabinoid system is critical to how humans modulate between a satisfying degree of arousal compared to a level that is excessive and unpleasant. The ECS also plays a role in memory formation and possibly especially in the way in which the brain imprints memories from stress or injury. Because the ECS modulates the release of dopamine, noradrenaline, serotonin, and cortisol, it can also widely influence emotional response and behaviors.

Digestive System

The digestive tract is populated with both CB1 and CB2 receptors that regulate several important aspects of GI health. It’s thought that the ECS might be the “missing link” in describing the gut-brain-immune link that plays a significant role in the functional health of the digestive tract. The ECS is a regulator of gut immunity, perhaps by limiting the immune system from destroying healthy flora, and also through the modulation of cytokine signaling. The ECS modulates the natural inflammatory response in the digestive tract, which has important implications for a wide range of health issues. Gastric and general GI motility also appears to be partially governed by the ECS.

Appetite and Metabolism

The ECS, particularly the CB1 receptors, plays a part in appetite, metabolism, and regulation of body fat. Stimulation of the CB1 receptors raises food-seeking behaviour, enhances awareness of smell, also regulates energy balance. Both animals and humans that are overweight have ECS dysregulation that may lead this system to become hyperactive, which contributes to both overeating and reduced energy expenditure. Circulating levels of anandamide and 2-AG have been shown to be elevated in obesity, which might be in part due to decreased production of the FAAH degrading enzyme.

Immune Health and Inflammatory Response

The cells and organs of the immune system are rich with endocannabinoid receptors. Cannabinoid receptors are expressed in the thymus gland, spleen, tonsils, and bone marrow, as well as on T- and B-lymphocytes, macrophages, mast cells, neutrophils, and natural killer cells. The ECS is regarded as the primary driver of immune system balance and homeostasis. Though not all the functions of the ECS from the immune system are understood, the ECS appears to regulate cytokine production and also to have a role in preventing overactivity in the immune system. Inflammation is a natural part of the immune response, and it plays a very normal role in acute insults to the body, including injury and disease ; nonetheless, when it isn’t kept in check it can become chronic and contribute to a cascade of adverse health problems, such as chronic pain. By keeping the immune response in check, the ECS helps to maintain a more balanced inflammatory response through the body.

Other areas of health regulated by the ECS:

- Bone health

- Fertility

- Skin health

- Arterial and respiratory health

- Sleep and circadian rhythm

How to best support a healthy ECS is a question many researchers are now trying to answer. Stay tuned for more information on this emerging topic.

In conclusion,�chronic pain has been associated with brain changes, including the reduction of gray matter. However, the article above demonstrated that chronic pain can alter the overall structure and function of the brain. Although chronic pain may lead to these, among other health issues, the proper treatment of the patient’s underlying symptoms can reverse brain changes and regulate gray matter. Furthermore, more and more research studies have emerged behind the importance of the endocannabinoid system and it’s function in controlling as well as managing chronic pain and other health issues. Information referenced from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).�The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic as well as to spinal injuries and conditions. To discuss the subject matter, please feel free to ask Dr. Jimenez or contact us at�915-850-0900�.

Curated by Dr. Alex Jimenez

Additional Topics: Back Pain

Back pain is one of the most prevalent causes for disability and missed days at work worldwide. As a matter of fact, back pain has been attributed as the second most common reason for doctor office visits, outnumbered only by upper-respiratory infections. Approximately 80 percent of the population will experience some type of back pain at least once throughout their life. The spine is a complex structure made up of bones, joints, ligaments and muscles, among other soft tissues. Because of this, injuries and/or aggravated conditions, such as herniated discs, can eventually lead to symptoms of back pain. Sports injuries or automobile accident injuries are often the most frequent cause of back pain, however, sometimes the simplest of movements can have painful results. Fortunately, alternative treatment options, such as chiropractic care, can help ease back pain through the use of spinal adjustments and manual manipulations, ultimately improving pain relief.

EXTRA IMPORTANT TOPIC: Low Back Pain Management

MORE TOPICS: EXTRA EXTRA:�Chronic Pain & Treatments

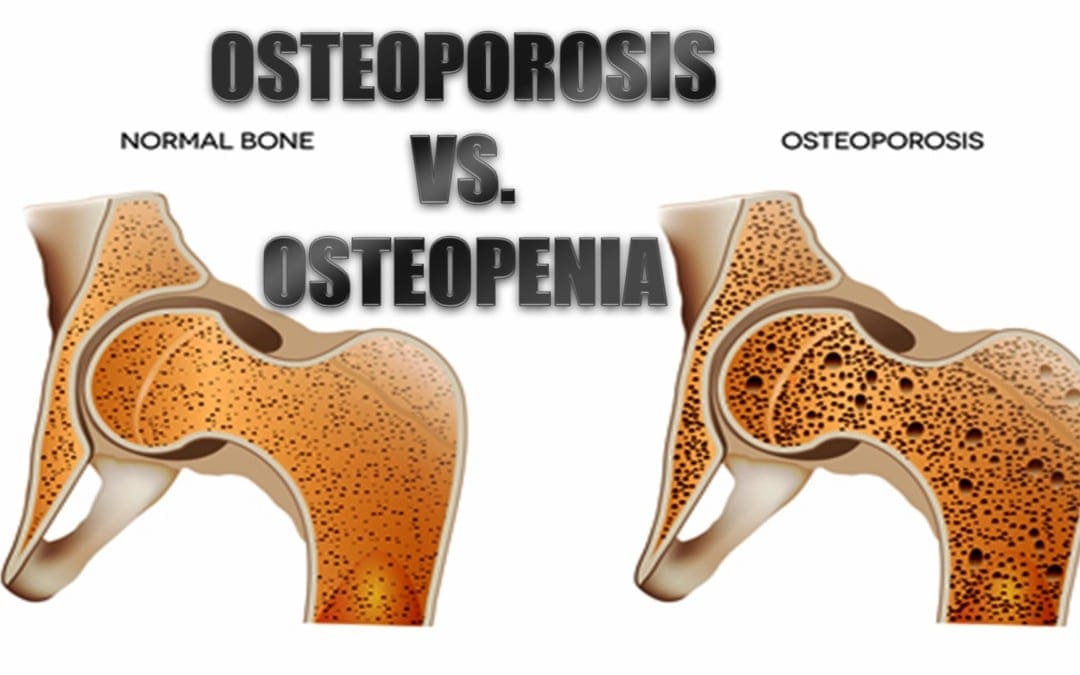

What Is Osteoporosis?

What Is Osteoporosis?

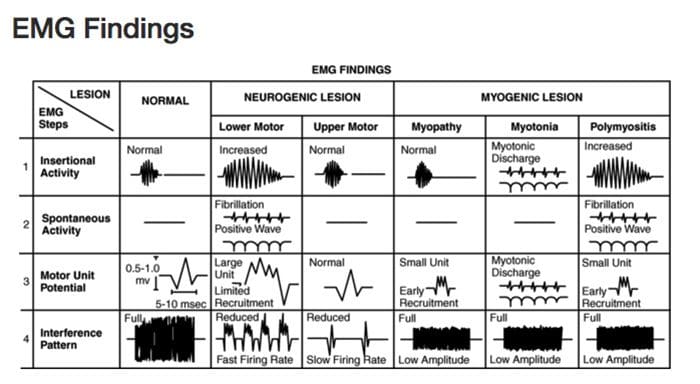

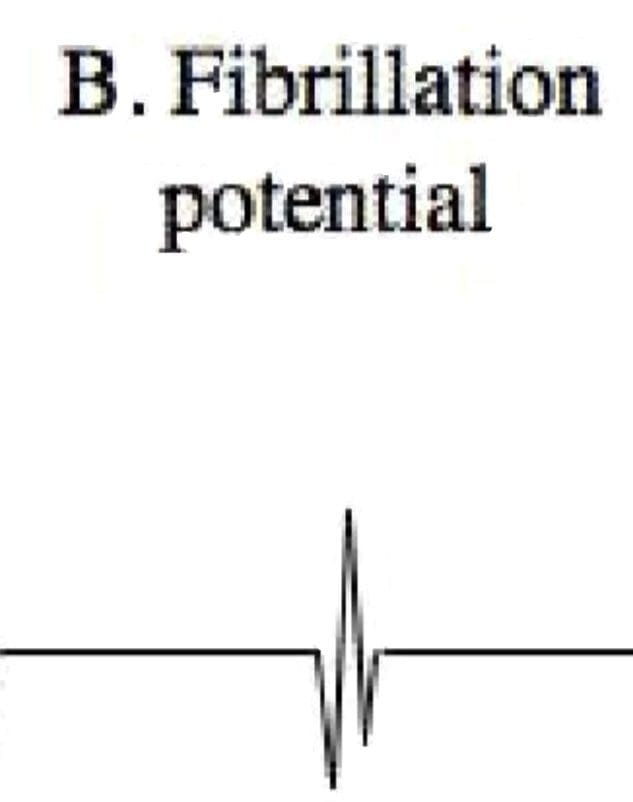

Diagnostic Needle EMG

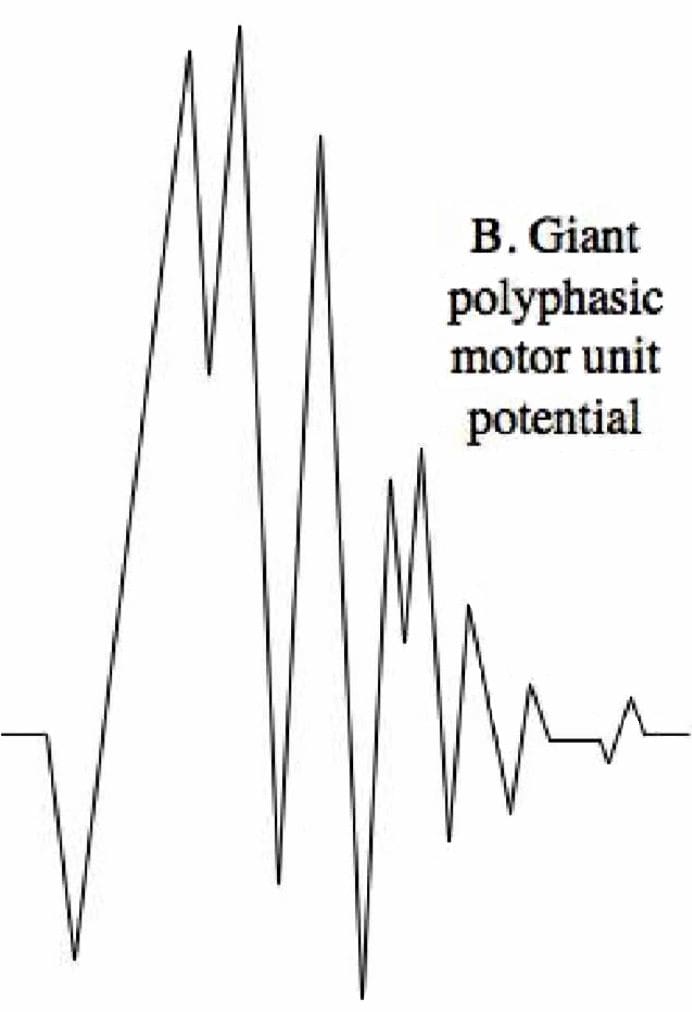

Diagnostic Needle EMG Polyphasic MUPS

Polyphasic MUPS Complete Potential Blocks

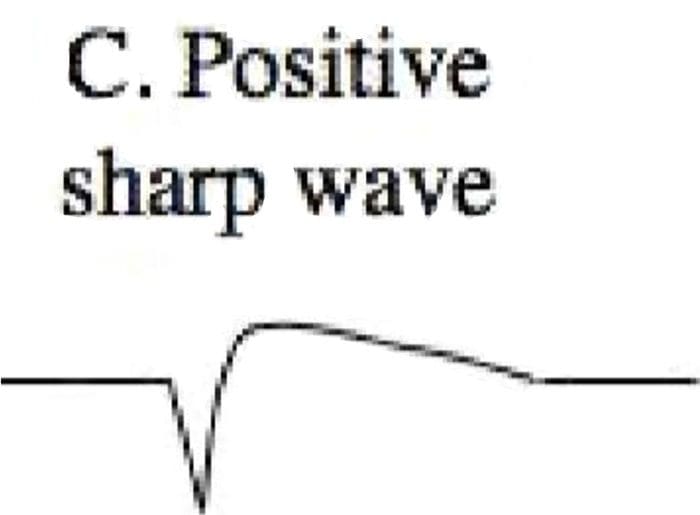

Complete Potential Blocks Positive Sharp Waves

Positive Sharp Waves Abnormal Findings

Abnormal Findings

Why Does My Shoulder Hurt? A Review Of The Neuroanatomical & Biochemical Basis Of Shoulder Pain

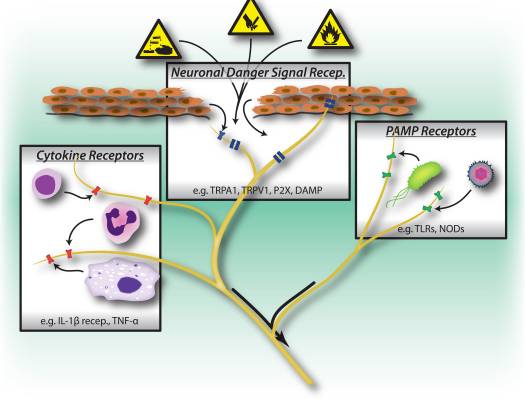

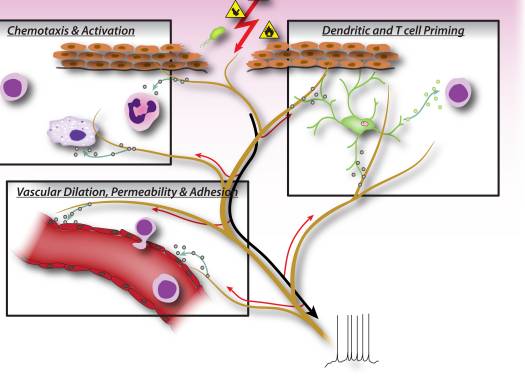

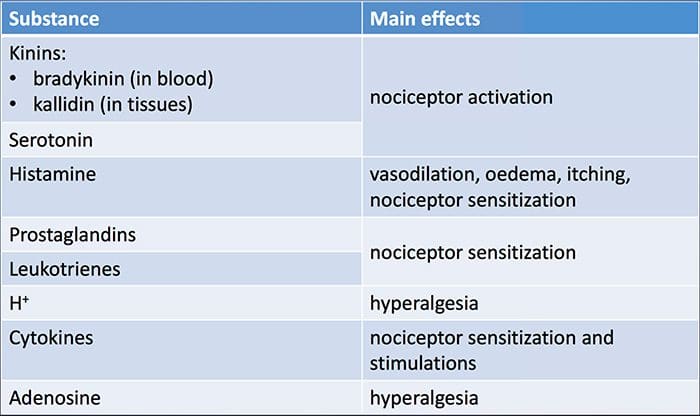

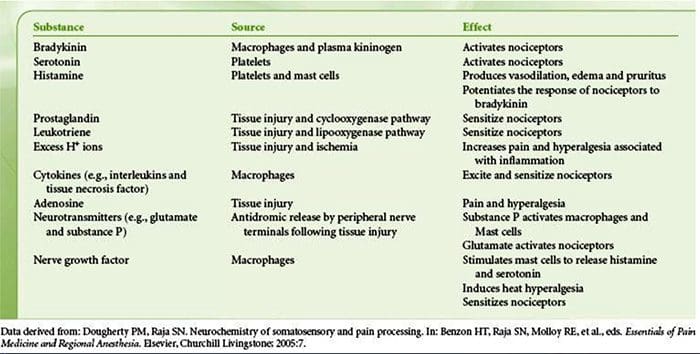

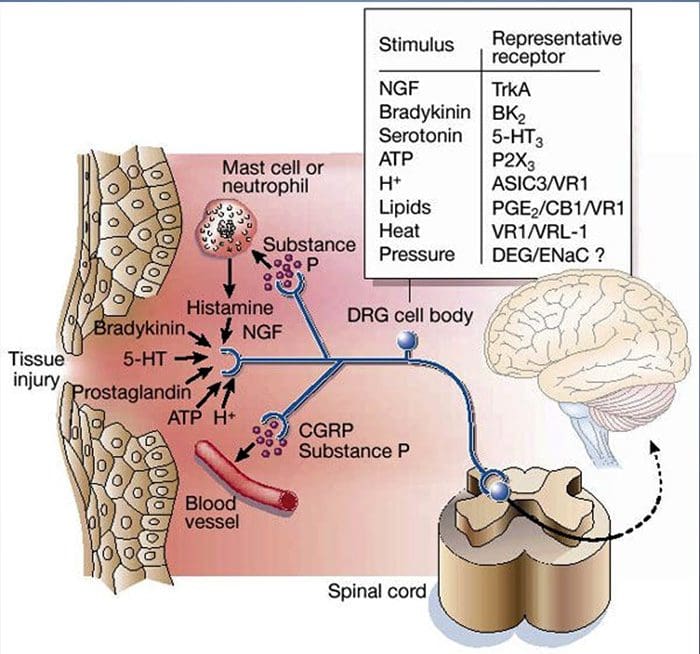

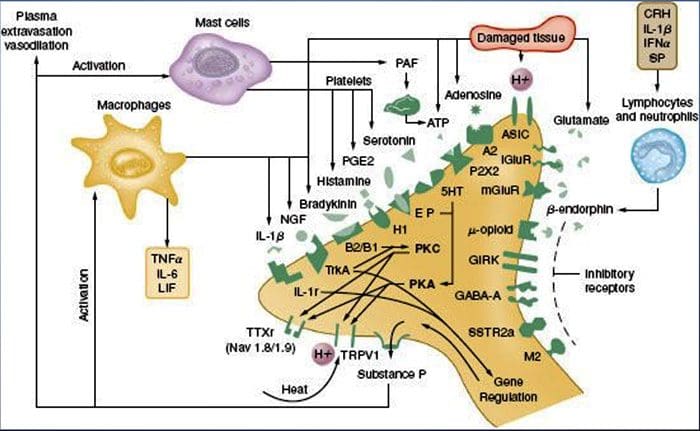

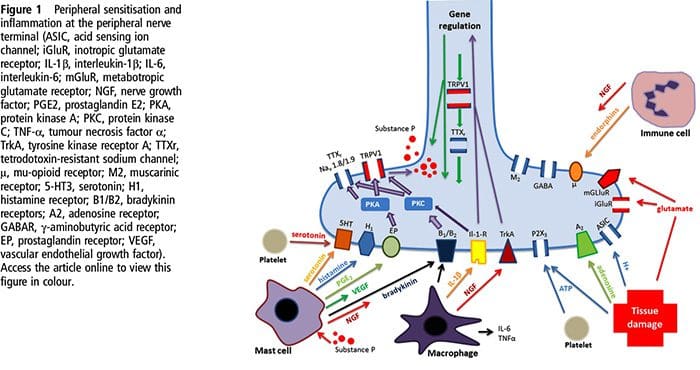

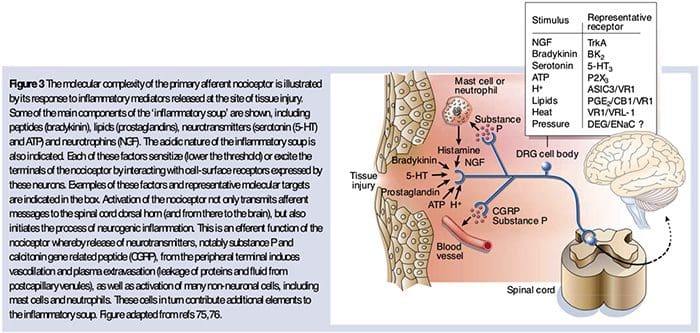

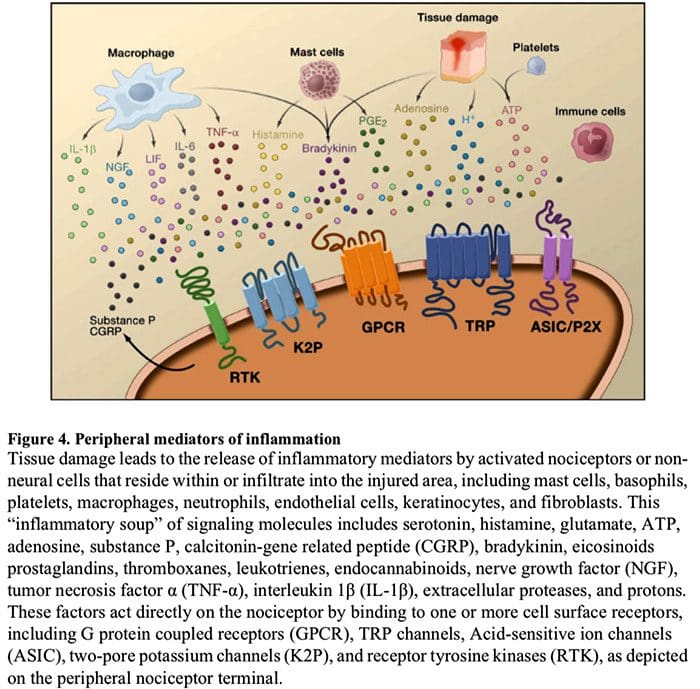

Why Does My Shoulder Hurt? A Review Of The Neuroanatomical & Biochemical Basis Of Shoulder Pain NGF and the transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 (TRPV1) receptor have a symbiotic relationship when it comes to inflammation and nociceptor sensitization. The cytokines produced in inflamed tissue result in an increase in NGF production.19 NGF stimulates the release of histamine and serotonin (5-HT3) by mast cells, and also sensitizes nociceptors, possibly altering the properties of A? fibers such that a greater proportion become nociceptive. The TRPV1 receptor is present in a subpopulation of primary afferent fibers and is activated by capsaicin, heat and protons. The TRPV1 receptor is synthesized in the cell body of the afferent fibre, and is transported to both the peripheral and central terminals, where it contributes to the sensitivity of nociceptive afferents. Inflammation results in NGF production peripherally which then binds to the tyrosine kinase receptor type 1 receptor on the nociceptor terminals, NGF is then transported to the cell body where it leads to an up regulation of TRPV1 transcription and consequently increased nociceptor sensitivity.19 20 NGF and other inflammatory mediators also sensitize TRPV1 through a diverse array of secondary messenger pathways. Many other receptors including cholinergic receptors, ?-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors and somatostatin receptors are also thought to be involved in peripheral nociceptor sensitivity.

NGF and the transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 (TRPV1) receptor have a symbiotic relationship when it comes to inflammation and nociceptor sensitization. The cytokines produced in inflamed tissue result in an increase in NGF production.19 NGF stimulates the release of histamine and serotonin (5-HT3) by mast cells, and also sensitizes nociceptors, possibly altering the properties of A? fibers such that a greater proportion become nociceptive. The TRPV1 receptor is present in a subpopulation of primary afferent fibers and is activated by capsaicin, heat and protons. The TRPV1 receptor is synthesized in the cell body of the afferent fibre, and is transported to both the peripheral and central terminals, where it contributes to the sensitivity of nociceptive afferents. Inflammation results in NGF production peripherally which then binds to the tyrosine kinase receptor type 1 receptor on the nociceptor terminals, NGF is then transported to the cell body where it leads to an up regulation of TRPV1 transcription and consequently increased nociceptor sensitivity.19 20 NGF and other inflammatory mediators also sensitize TRPV1 through a diverse array of secondary messenger pathways. Many other receptors including cholinergic receptors, ?-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors and somatostatin receptors are also thought to be involved in peripheral nociceptor sensitivity. The Neurochemistry Of Nociceptors

The Neurochemistry Of Nociceptors Cellular & Molecular Mechanisms Of Pain

Cellular & Molecular Mechanisms Of Pain

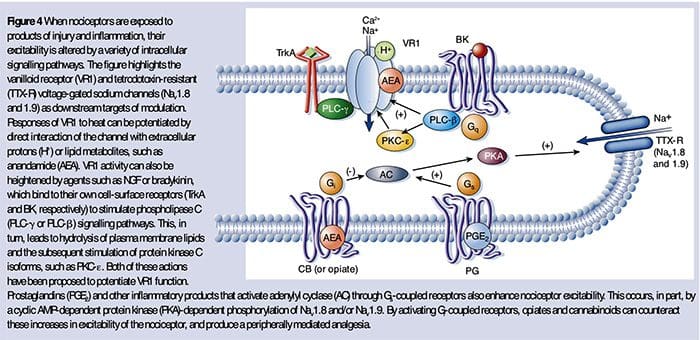

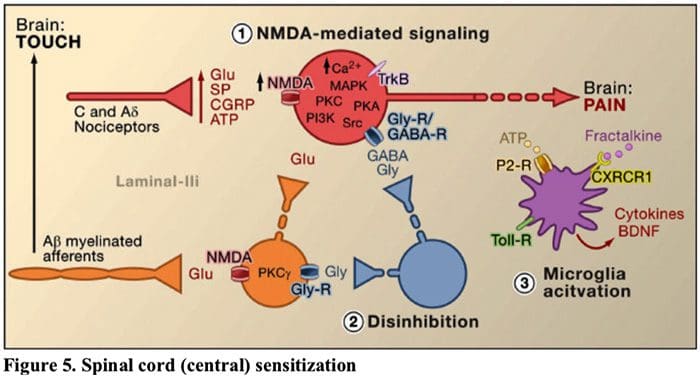

Figure 5. Spinal Cord (Central) Sensitization

Figure 5. Spinal Cord (Central) Sensitization