1. Kayser MS, Dalmau J: The emerging link between autoimmune disorders

and neuropsychiatric disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2011, 23:90�97.

2. Najjar S, Pearlman D, Zagzag D, Golfinos J, Devinsky O: Glutamic acid

decarboxylase autoantibody syndrome presenting as schizophrenia.

Neurologist 2012, 18:88�91.

3. Graus F, Saiz A, Dalmau J: Antibodies and neuronal autoimmune

disorders of the CNS. J Neurol 2010, 257:509�517.

4. Lennox BR, Coles AJ, Vincent A: Antibody-mediated encephalitis: a

treatable cause of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 2012, 200:92�94.

5. Zandi MS, Irani SR, Lang B, Waters P, Jones PB, McKenna P, Coles AJ, Vincent

A, Lennox BR: Disease-relevant autoantibodies in first episode

schizophrenia. J Neurol 2011, 258:686�688.

6. Bataller L, Kleopa KA, Wu GF, Rossi JE, Rosenfeld MR, Dalmau J:

Autoimmune limbic encephalitis in 39 patients: immunophenotypes and

outcomes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2007, 78:381�385.

7. Dale RC, Heyman I, Giovannoni G, Church AW: Incidence of anti-brain

antibodies in children with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Br J Psychiatry

2005, 187:314�319.

8. Kendler KS: The dappled nature of causes of psychiatric illness: replacing

the organic-functional/hardware-software dichotomy with empirically

based pluralism. Mol Psychiatry 2012, 17:377�388.

9. Keskin G, Sunter G, Midi I, Tuncer N: Neurosyphilis as a cause of cognitive

decline and psychiatric symptoms at younger age. J Neuropsychiatry Clin

Neurosci 2011, 23:E41�E42.

10. Leboyer M, Soreca I, Scott J, Frye M, Henry C, Tamouza R, Kupfer DJ: Can

bipolar disorder be viewed as a multi-system inflammatory disease?

J Affect Disord 2012, 141:1�10.

11. Hackett ML, Yapa C, Parag V, Anderson CS: Frequency of depression after

stroke: a systematic review of observational studies. Stroke 2005, 36:1330�1340.

12. Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW: From

inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system

subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci 2008, 9:46�56.

13. Laske C, Zank M, Klein R, Stransky E, Batra A, Buchkremer G, Schott K:

Autoantibody reactivity in serum of patients with major depression,

schizophrenia and healthy controls. Psychiatry Res 2008, 158:83�86.

14. Eisenberger NI, Berkman ET, Inagaki TK, Rameson LT, Mashal NM, Irwin MR:

Inflammation-induced anhedonia: endotoxin reduces ventral striatum

responses to reward. Biol Psychiatry 2010, 68:748�754.

15. Haroon E, Raison CL, Miller AH: Psychoneuroimmunology meets

neuropsychopharmacology: translational implications of the impact of

inflammation on behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology 2012, 37:137�162.

16. Benros ME, Nielsen PR, Nordentoft M, Eaton WW, Dalton SO, Mortensen PB:

Autoimmune diseases and severe infections as risk factors for

schizophrenia: a 30-year population-based register study. Am J Psychiatry

2011, 168:1303�1310.

17. McNally L, Bhagwagar Z, Hannestad J: Inflammation, glutamate, and glia

in depression: a literature review. CNS Spectr 2008, 13:501�510.

18. Harrison NA, Brydon L, Walker C, Gray MA, Steptoe A, Critchley HD:

Inflammation causes mood changes through alterations in subgenual

cingulate activity and mesolimbic connectivity. Biol Psychiatry 2009,

66:407�414.19. Raison CL, Miller AH: Is depression an inflammatory disorder?

Curr Psychiatry Rep 2011, 13:467�475.

20. Raison CL, Miller AH: The evolutionary significance of depression in

Pathogen Host Defense (PATHOS-D). Mol Psychiatry 2013, 18:15�37.

21. Steiner J, Bogerts B, Sarnyai Z, Walter M, Gos T, Bernstein HG, Myint AM:

Bridging the gap between the immune and glutamate hypotheses of

schizophrenia and major depression: Potential role of glial NMDA

receptor modulators and impaired blood�brain barrier integrity. World J

Biol Psychiatry 2012, 13:482�492.

22. Steiner J, Mawrin C, Ziegeler A, Bielau H, Ullrich O, Bernstein HG, Bogerts B:

Distribution of HLA-DR-positive microglia in schizophrenia reflects

impaired cerebral lateralization. Acta Neuropathol 2006, 112:305�316.

23. Papakostas GI, Shelton RC, Kinrys G, Henry ME, Bakow BR, Lipkin SH, Pi B,

Thurmond L, Bilello JA: Assessment of a multi-assay, serum-based

biological diagnostic test for major depressive disorder: a pilot and

replication study. Mol Psychiatry 2013, 18:332�339.

24. Krishnan R: Unipolar depression in adults: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and

neurobiology. In UpToDate. Edited by Basow DS. Waltham, MA: UpToDate; 2013.

25. Stovall J: Bipolar disorder in adults: epidemiology and diagnosis. In

UpToDate. Edited by Basow DS. UpToDate: Waltham; 2013.

26. Fischer BA, Buchanan RW: Schizophrenia: epidemiology and pathogenesis.

In UpToDate. Edited by Basow DS. Waltham, MA: UpToDate; 2013.

27. Nestadt G, Samuels J, Riddle M, Bienvenu OJ 3rd, Liang KY, LaBuda M,

Walkup J, Grados M, Hoehn-Saric R: A family study of obsessivecompulsive

disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000, 57:358�363.

28. Stefansson H, Ophoff RA, Steinberg S, Andreassen OA, Cichon S, Rujescu D,

Werge T, Pietilainen OP, Mors O, Mortensen PB, Sigurdsson E, Gustafsson O,

Nyegaard M, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Ingason A, Hansen T, Suvisaari J,

Lonnqvist J, Paunio T, B�rglum AD, Hartmann A, Fink-Jensen A, Nordentoft

M, Hougaard D, Norgaard-Pedersen B, B�ttcher Y, Olesen J, Breuer R, M�ller

HJ, Giegling I, et al: Common variants conferring risk of schizophrenia.

Nature 2009, 460:744�747.

29. M�ller N, Schwarz MJ: The immune-mediated alteration of serotonin and

glutamate: towards an integrated view of depression. Mol Psychiatry

2007, 12:988�1000.

30. Galecki P, Florkowski A, Bienkiewics M, Szemraj J: Functional polymorphism

of cyclooxygenase-2 gene (G-765C) in depressive patients.

Neuropsychobiology 2010, 62:116�120.

31. Levinson DF: The genetics of depression: a review. Biol Psychiatry 2006,

60:84�92.

32. Zhai J, Cheng L, Dong J, Shen Q, Zhang Q, Chen M, Gao L, Chen X, Wang K,

Deng X, Xu Z, Ji F, Liu C, Li J, Dong Q, Chen C: S100B gene

polymorphisms predict prefrontal spatial function in both schizophrenia

patients and healthy individuals. Schizophr Res 2012, 134:89�94.

33. Zhai J, Zhang Q, Cheng L, Chen M, Wang K, Liu Y, Deng X, Chen X, Shen Q,

Xu Z, Ji F, Liu C, Dong Q, Chen C, Li J: Risk variants in the S100B gene,

associated with elevated S100B levels, are also associated with

visuospatial disability of schizophrenia. Behav Brain Res 2011, 217:363�368.

34. Cappi C, Muniz RK, Sampaio AS, Cordeiro Q, Brentani H, Palacios SA,

Marques AH, Vallada H, Miguel EC, Guilherme L, Hounie AG: Association

study between functional polymorphisms in the TNF-alpha gene and

obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2012, 70:87�90.

35. Miguel-Hidalgo JJ, Baucom C, Dilley G, Overholser JC, Meltzer HY,

Stockmeier CA, Rajkowska G: Glial fibrillary acidic protein

immunoreactivity in the prefrontal cortex distinguishes younger from

older adults in major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2000, 48:861�873.

36. Altshuler LL, Abulseoud OA, Foland Ross L, Bartzokis G, Chang S, Mintz J,

Hellemann G, Vinters HV: Amygdala astrocyte reduction in subjects with

major depressive disorder but not bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 2010,

12:541�549.

37. Webster MJ, Knable MB, Johnston-Wilson N, Nagata K, Inagaki M, Yolken RH:

Immunohistochemical localization of phosphorylated glial fibrillary acidic

protein in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus from patients with

schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression. Brain Behav Immun 2001,

15:388�400.

38. Doyle C, Deakin JFW: Fewer astrocytes in frontal cortex in schizophrenia,

depression and bipolar disorder. Schizophrenia Res 2002, 53:106.

39. Johnston-Wilson NL, Sims CD, Hofmann JP, Anderson L, Shore AD, Torrey

EF, Yolken RH: Disease-specific alterations in frontal cortex brain proteins

in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder, The

Stanley Neuropathology Consortium. Mol Psychiatry 2000, 5:142�149.

40. Gosselin RD, Gibney S, O’Malley D, Dinan TG, Cryan JF: Region specific

decrease in glial fibrillary acidic protein immunoreactivity in the brain of

a rat model of depression. Neuroscience 2009, 159:915�925.

41. Banasr M, Duman RS: Glial loss in the prefrontal cortex is sufficient to

induce depressive-like behaviors. Biol Psychiatry 2008, 64:863�870.

42. Cotter D, Hudson L, Landau S: Evidence for orbitofrontal pathology in

bipolar disorder and major depression, but not in schizophrenia.

Bipolar Disord 2005, 7:358�369.

43. Brauch RA, Adnan El-Masri M, Parker J Jr, El-Mallakh RS: Glial cell number

and neuron/glial cell ratios in postmortem brains of bipolar individuals.

J Affect Disord 2006, 91:87�90.

44. Cotter DR, Pariante CM, Everall IP: Glial cell abnormalities in major

psychiatric disorders: the evidence and implications. Brain Res Bull 2001,

55:585�595.

45. Cotter D, Mackay D, Landau S, Kerwin R, Everall I: Reduced glial cell density

and neuronal size in the anterior cingulate cortex in major depressive

disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001, 58:545�553.

46. Bowley MP, Drevets WC, Ong�r D, Price JL: Low glial numbers in the

amygdala in major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2002, 52:404�412.

47. Toro CT, Hallak JE, Dunham JS, Deakin JF: Glial fibrillary acidic protein and

glutamine synthetase in subregions of prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia

and mood disorder. Neurosci Lett 2006, 404:276�281.

48. Rajkowska G, Miguel-Hidalgo JJ, Makkos Z, Meltzer H, Overholser J,

Stockmeier C: Layer-specific reductions in GFAP-reactive astroglia in the

dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2002, 57:127�138.

49. Steffek AE, McCullumsmith RE, Haroutunian V, Meador-Woodruff JH: Cortical

expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein and glutamine synthetase is

decreased in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2008, 103:71�82.

50. Damadzic R, Bigelow LB, Krimer LS, Goldenson DA, Saunders RC, Kleinman

JE, Herman MM: A quantitative immunohistochemical study of astrocytes in

the entorhinal cortex in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major

depression: absence of significant astrocytosis. Brain Res Bull 2001, 55:611�618.

51. Benes FM, McSparren J, Bird ED, SanGiovanni JP, Vincent SL: Deficits in

small interneurons in prefrontal and cingulate cortices of schizophrenic

and schizoaffective patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991, 48:996�1001.

52. M�ller N, Schwarz MJ: Immune system and schizophrenia. Curr Immunol

Rev 2010, 6:213�220.

53. Steiner J, Walter M, Gos T, Guillemin GJ, Bernstein HG, Sarnyai Z, Mawrin C,

Brisch R, Bielau H, Meyer Zu Schwabedissen L, Bogerts B, Myint AM: Severe

depression is associated with increased microglial quinolinic acid in

subregions of the anterior cingulate gyrus: evidence for an immunemodulated

glutamatergic neurotransmission? J Neuroinflammation 2011, 8:94.

54. Vostrikov VM, Uranova NA, Orlovskaya DD: Deficit of perineuronal

oligodendrocytes in the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia and mood

disorders. Schizophr Res 2007, 94:273�280.

55. Rajkowska G, Miguel-Hidalgo JJ: Gliogenesis and glial pathology in

depression. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2007, 6:219�233.

56. Uranova NA, Vostrikov VM, Orlovskaya DD, Rachmanova VI:

Oligodendroglial density in the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia and

mood disorders: a study from the Stanley Neuropathology Consortium.

Schizophr Res 2004, 67:269�275.

57. Uranova N: Damage and loss of oligodendrocytes are crucial in the

pathogenesis of schizophrenia and mood disorders (findings form

postmortem studies). Neuropsychopharmacology 2004, 29:S33.

58. Uranova NA, Orlovskaya DD, Vostrikov VM, Rachmanova VI: Decreased

density of oligodendroglial satellites of pyramidal neurons in layer III in

the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia and mood disorders. Schizophr Res

2002, 53:107.

59. Vostrikov VM, Uranova NA, Rakhmanova VI, Orlovskaia DD: Lowered

oligodendroglial cell density in the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia.

Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova 2004, 104:47�51.

60. Uranova NA, Zimina IS, Vikhreva OV, Krukov NO, Rachmanova VI, Orlovskaya

DD: Ultrastructural damage of capillaries in the neocortex in

schizophrenia. World J Biol Psychiatry 2010, 11:567�578.

61. Hof PR, Haroutunian V, Friedrich VL Jr, Byne W, Buitron C, Perl DP, Davis KL:

Loss and altered spatial distribution of oligodendrocytes in the superior

frontal gyrus in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2003, 53:1075�1085.

62. Davis KL, Stewart DG, Friedman JI, Buchsbaum M, Harvey PD, Hof PR,

Buxbaum J, Haroutunian V: White matter changes in schizophrenia:

evidence for myelin-related dysfunction. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003,

60:443�456.63. Flynn SW, Lang DJ, Mackay AL, Goghari V, Vavasour IM, Whittall KP, Smith

GN, Arango V, Mann JJ, Dwork AJ, Falkai P, Honer WG: Abnormalities of

myelination in schizophrenia detected in vivo with MRI, and postmortem

with analysis of oligodendrocyte proteins. Mol Psychiatry 2003,

8:811�820.

64. Uranova NA, Vostrikov VM, Vikhreva OV, Zimina IS, Kolomeets NS, Orlovskaya

DD: The role of oligodendrocyte pathology in schizophrenia. Int J

Neuropsychopharmacol 2007, 10:537�545.

65. Byne W, Kidkardnee S, Tatusov A, Yiannoulos G, Buchsbaum MS,

Haroutunian V: Schizophrenia-associated reduction of neuronal and

oligodendrocyte numbers in the anterior principal thalamic nucleus.

Schizophr Res 2006, 85:245�253.

66. Hamidi M, Drevets WC, Price JL: Glial reduction in amygdala in major

depressive disorder is due to oligodendrocytes. Biol Psychiatry 2004,

55:563�569.

67. Bayer TA, Buslei R, Havas L, Falkai P: Evidence for activation of microglia in

patients with psychiatric illnesses. Neurosci Lett 1999, 271:126�128.

68. Steiner J, Bielau H, Brisch R, Danos P, Ullrich O, Mawrin C, Bernstein HG,

Bogerts B: Immunological aspects in the neurobiology of suicide:

elevated microglial density in schizophrenia and depression is

associated with suicide. J Psychiatr Res 2008, 42:151�157.

69. Rao JS, Harry GJ, Rapoport SI, Kim HW: Increased excitotoxicity and

neuroinflammatory markers in postmortem frontal cortex from bipolar

disorder patients. Mol Psychiatry 2010, 15:384�392.

70. Bernstein HG, Steiner J, Bogerts B: Glial cells in schizophrenia:

pathophysiological significance and possible consequences for therapy.

Expert Rev Neurother 2009, 9:1059�1071.

71. Chen SK, Tvrdik P, Peden E, Cho S, Wu S, Spangrude G, Capecchi MR:

Hematopoietic origin of pathological grooming in Hoxb8 mutant mice.

Cell 2010, 141:775�785.

72. Antony JM: Grooming and growing with microglia. Sci Signal 2010, 3:jc8.

73. Wonodi I, Stine OC, Sathyasaikumar KV, Roberts RC, Mitchell BD, Hong LE,

Kajii Y, Thaker GK, Schwarcz R: Downregulated kynurenine 3-

monooxygenase gene expression and enzyme activity in schizophrenia

and genetic association with schizophrenia endophenotypes. Arch Gen

Psychiatry 2011, 68:665�674.

74. Raison CL, Lowry CA, Rook GA: Inflammation, sanitation, and

consternation: loss of contact with coevolved, tolerogenic

microorganisms and the pathophysiology and treatment of major

depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010, 67:1211�1224.

75. Drexhage RC, Hoogenboezem TH, Versnel MA, Berghout A, Nolen WA,

Drexhage HA: The activation of monocyte and T cell networks in patients

with bipolar disorder. Brain Behav Immun 2011, 25:1206�1213.

76. Steiner J, Jacobs R, Panteli B, Brauner M, Schiltz K, Bahn S, Herberth M,

Westphal S, Gos T, Walter M, Bernstein HG, Myint AM, Bogerts B: Acute

schizophrenia is accompanied by reduced T cell and increased B cell

immunity. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2010, 260:509�518.

77. Rotge JY, Aouizerate B, Tignol J, Bioulac B, Burbaud P, Guehl D: The

glutamate-based genetic immune hypothesis in obsessive-compulsive

disorder, An integrative approach from genes to symptoms.

Neuroscience 2010, 165:408�417.

78. Y�ksel C, Ong�r D: Magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies of

glutamate-related abnormalities in mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry 2010,

68:785�794.

79. Rao JS, Kellom M, Reese EA, Rapoport SI, Kim HW: Dysregulated glutamate

and dopamine transporters in postmortem frontal cortex from bipolar

and schizophrenic patients. J Affect Disord 2012, 136:63�71.

80. Bauer D, Gupta D, Harotunian V, Meador-Woodruff JH, McCullumsmith RE:

Abnormal expression of glutamate transporter and transporter

interacting molecules in prefrontal cortex in elderly patients with

schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2008, 104:108�120.

81. Matute C, Melone M, Vallejo-Illarramendi A, Conti F: Increased expression

of the astrocytic glutamate transporter GLT-1 in the prefrontal cortex of

schizophrenics. 2005, 49:451�455.

82. Smith RE, Haroutunian V, Davis KL, Meador-Woodruff JH: Expression of

excitatory amino acid transporter transcripts in the thalamus of subjects

with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2001, 158:1393�1399.

83. McCullumsmith RE, Meador-Woodruff JH: Striatal excitatory amino acid

transporter transcript expression in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder,

and major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 2002,

26:368�375.

84. Pittenger C, Bloch MH, Williams K: Glutamate abnormalities in obsessive

compulsive disorder: neurobiology, pathophysiology, and treatment.

Pharmacol Ther 2011, 132:314�332.

85. Hashimoto K: Emerging role of glutamate in the pathophysiology of

major depressive disorder. Brain Res Rev 2009, 61:105�123.

86. Hashimoto K, Sawa A, Iyo M: Increased levels of glutamate in brains from

patients with mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry 2007, 62:1310�1316.

87. Burbaeva G, Boksha IS, Turishcheva MS, Vorobyeva EA, Savushkina OK,

Tereshkina EB: Glutamine synthetase and glutamate dehydrogenase in

the prefrontal cortex of patients with schizophrenia. Prog

Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2003, 27:675�680.

88. Bhattacharyya S, Khanna S, Chakrabarty K, Mahadevan A, Christopher R,

Shankar SK: Anti-brain autoantibodies and altered excitatory

neurotransmitters in obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Neuropsychopharmacology 2009, 34:2489�2496.

89. Sanacora G, Gueorguieva R, Epperson CN, Wu YT, Appel M, Rothman DL,

Krystal JH, Mason GF: Subtype-specific alterations of gammaaminobutyric

acid and glutamate in patients with major depression.

Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004, 61:705�713.

90. Marsman A, van den Heuvel MP, Klomp DW, Kahn RS, Luijten PR, Hulshoff

Pol HE: Glutamate in schizophrenia: a focused review and meta-analysis

of 1H-MRS studies. Schizophr Bull 2013, 39:120�129.

91. Liu Y, Ho RC, Mak A: Interleukin (IL)-6, tumour necrosis factor alpha

(TNF-alpha) and soluble interleukin-2 receptors (sIL-2R) are elevated in

patients with major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis and metaregression.

J Affect Disord 2012, 139:230�239.

92. Brietzke E, Stabellini R, Grassis-Oliveira R, Lafer B: Cytokines in bipolar

disorder: recent findings, deleterious effects but promise for future

therapeutics. CNS Spectr 2011. http://www.cnsspectrums.com/aspx/

articledetail.aspx?articleid=3596.

93. Denys D, Fluitman S, Kavelaars A, Heijnen C, Westenberg H: Decreased

TNF-alpha and NK activity in obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Psychoneuroendocrinology 2004, 29:945�952.

94. Brambilla F, Perna G, Bellodi L, Arancio C, Bertani A, Perini G, Carraro C, Gava

F: Plasma interleukin-1 beta and tumor necrosis factor concentrations in

obsessive-compulsive disorders. Biol Psychiatry 1997, 42:976�981.

95. Fluitman S, Denys D, Vulink N, Schutters S, Heijnen C, Westenberg H:

Lipopolysaccharide-induced cytokine production in obsessivecompulsive

disorder and generalized social anxiety disorder. Psychiatry

Res 2010, 178:313�316.

96. Janelidze S, Mattei D, Westrin A, Traskman-Bendz L, Brundin L: Cytokine

levels in the blood may distinguish suicide attempters from depressed

patients. Brain Behav Immun 2011, 25:335�339.

97. Postal M, Costallat LT, Appenzeller S: Neuropsychiatric manifestations in

systemic lupus erythematosus: epidemiology, pathophysiology and

management. CNS Drugs 2011, 25:721�736.

98. Kozora E, Hanly JG, Lapteva L, Filley CM: Cognitive dysfunction in

systemic lupus erythematosus: past, present, and future.

Arthritis Rheum 2008, 58:3286�3298.

99. Lancaster E, Martinez-Hernandez E, Dalmau J: Encephalitis and antibodies to

synaptic and neuronal cell surface proteins. Neurology 2011, 77:179�189.

100. Dalmau J, Lancaster E, Martinez-Hernandez E, Rosenfeld MR, Balice-Gordon

R: Clinical experience and laboratory investigations in patients with antiNMDAR

encephalitis. Lancet Neurol 2011, 10:63�74.

101. Lai M, Huijbers MG, Lancaster E, Graus F, Bataller L, Balice-Gordon R, Cowell

JK, Dalmau J: Investigation of LGI1 as the antigen in limbic encephalitis

previously attributed to potassium channels: a case series. Lancet Neurol

2010, 9:776�785.

102. Lancaster E, Huijbers MG, Bar V, Boronat A, Wong A, Martinez-Hernandez E,

Wilson C, Jacobs D, Lai M, Walker RW, Graus F, Bataller L, Illa I, Markx S, Strauss

KA, Peles E, Scherer SS, Dalmau J: Investigations of caspr2, an autoantigen of

encephalitis and neuromyotonia. Ann Neurol 2011, 69:303�311.

103. Lancaster E, Lai M, Peng X, Hughes E, Constantinescu R, Raizer J, Friedman

D, Skeen MB, Grisold W, Kimura A, Ohta K, Iizuka T, Guzman M, Graus F,

Moss SJ, Balice-Gordon R, Dalmau J: Antibodies to the GABA(B) receptor in

limbic encephalitis with seizures: case series and characterisation of the

antigen. Lancet Neurol 2010, 9:67�76.

104. Lancaster E, Martinez-Hernandez E, Titulaer MJ, Boulos M, Weaver S, Antoine

JC, Liebers E, Kornblum C, Bien CG, Honnorat J, Wong S, Xu J, Contractor A,

Balice-Gordon R, Dalmau J: Antibodies to metabotropic glutamate

receptor 5 in the Ophelia syndrome. Neurology 2011, 77:1698�1701.105. Ances BM, Vitaliani R, Taylor RA, Liebeskind DS, Voloschin A, Houghton DJ,

Galetta SL, Dichter M, Alavi A, Rosenfeld MR, Dalmau J: Treatmentresponsive

limbic encephalitis identified by neuropil antibodies: MRI and

PET correlates. Brain 2005, 128:1764�1777.

106. Tofaris GK, Irani SR, Cheeran BJ, Baker IW, Cader ZM, Vincent A:

Immunotherapy-responsive chorea as the presenting feature of LGI1-

antibody encephalitis. Neurology 2012, 79:195�196.

107. Najjar S, Pearlman D, Najjar A, Ghiasian V, Zagzag D, Devinsky O:

Extralimbic autoimmune encephalitis associated with glutamic acid

decarboxylase antibodies: an underdiagnosed entity? Epilepsy Behav

2011, 21:306�313.

108. Titulaer MJ, McCracken L, Gabilondo I, Armangue T, Glaser C, Iizuka T, Honig

LS, Benseler SM, Kawachi I, Martinez-Hernandez E, Aguilar E, Gresa-Arribas N,

Ryan-Florance N, Torrents A, Saiz A, Rosenfeld MR, Balice-Gordon R, Graus F,

Dalmau J: Treatment and prognostic factors for long-term outcome in

patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis: an observational cohort

study. Lancet Neurol 2013, 12:157�165.

109. Dalmau J, Gleichman AJ, Hughes EG, Rossi JE, Peng X, Lai M, Dessain SK,

Rosenfeld MR, Balice-Gordon R, Lynch DR: Anti-NMDA-receptor

encephalitis: case series and analysis of the effects of antibodies.

Lancet Neurol 2008, 7:1091�1098.

110. Graus F, Boronat A, Xifro X, Boix M, Svigelj V, Garcia A, Palomino A, Sabater

L, Alberch J, Saiz A: The expanding clinical profile of anti-AMPA receptor

encephalitis. Neurology 2010, 74:857�859.

111. Lai M, Hughes EG, Peng X, Zhou L, Gleichman AJ, Shu H, Mata S, Kremens

D, Vitaliani R, Geschwind MD, Bataller L, Kalb RG, Davis R, Graus F, Lynch DR,

Balice-Gordon R, Dalmau J: AMPA receptor antibodies in limbic

encephalitis alter synaptic receptor location. Ann Neurol 2009, 65:424�434.

112. Najjar S, Pearlman D, Devinsky O, Najjar A, Nadkarni S, Butler T, Zagzag D:

Neuropsychiatric autoimmune encephalitis with negative VGKC-complex,

NMDAR, and GAD autoantibodies: a case report and literature review,

forthcoming. Cogn Behav Neurol. in press.

113. Najjar S, Pearlman D, Zagzag D, Devinsky O: Spontaneously resolving

seronegative autoimmune limbic encephalitis. Cogn Behav Neurol 2011,

24:99�105.

114. Gabilondo I, Saiz A, Galan L, Gonzalez V, Jadraque R, Sabater L, Sans A,

Sempere A, Vela A, Villalobos F, Vi�als M, Villoslada P, Graus F: Analysis of

relapses in anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Neurology 2011, 77:996�999.

115. Barry H, Hardiman O, Healy DG, Keogan M, Moroney J, Molnar PP, Cotter

DR, Murphy KC: Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis: an important

differential diagnosis in psychosis. Br J Psychiatry 2011, 199:508�509.

116. Dickerson F, Stallings C, Vaughan C, Origoni A, Khushalani S, Yolken R:

Antibodies to the glutamate receptor in mania. Bipolar Disord 2012,

14:547�553.

117. O’Loughlin K, Ruge P, McCauley M: Encephalitis and schizophrenia: a

matter of words. Br J Psychiatry 2012, 201:74.

118. Parratt KL, Allan M, Lewis SJ, Dalmau J, Halmagyi GM, Spies JM: Acute

psychiatric illness in a young woman: an unusual form of encephalitis.

Med J Aust 2009, 191:284�286.

119. Suzuki Y, Kurita T, Sakurai K, Takeda Y, Koyama T: Case report of anti-NMDA

receptor encephalitis suspected of schizophrenia. Seishin Shinkeigaku

Zasshi 2009, 111:1479�1484.

120. Tsutsui K, Kanbayashi T, Tanaka K, Boku S, Ito W, Tokunaga J, Mori A,

Hishikawa Y, Shimizu T, Nishino S: Anti-NMDA-receptor antibody detected

in encephalitis, schizophrenia, and narcolepsy with psychotic features.

BMC Psychiatry 2012, 12:37.

121. Van Putten WK, Hachimi-Idrissi S, Jansen A, Van Gorp V, Huyghens L:

Uncommon cause of psychotic behavior in a 9-year-old girl: a case

report. Case Report Med 2012, 2012:358520.

122. Masdeu JC, Gonzalez-Pinto A, Matute C, Ruiz De Azua S, Palomino A, De

Leon J, Berman KF, Dalmau J: Serum IgG antibodies against the NR1

subunit of the NMDA receptor not detected in schizophrenia. Am J

Psychiatry 2012, 169:1120�1121.

123. Kirvan CA, Swedo SE, Kurahara D, Cunningham MW: Streptococcal mimicry

and antibody-mediated cell signaling in the pathogenesis of

Sydenham’s chorea. Autoimmunity 2006, 39:21�29.

124. Swedo SE: Streptoccocal infection, Tourette syndrome, and OCD: is there

a connection? Pandas: Horse or zebra? Neurology 2010, 74:1397�1398.

125. Morer A, Lazaro L, Sabater L, Massana J, Castro J, Graus F: Antineuronal

antibodies in a group of children with obsessive-compulsive disorder

and Tourette syndrome. J Psychiatr Res 2008, 42:64�68.

126. Pavone P, Bianchini R, Parano E, Incorpora G, Rizzo R, Mazzone L, Trifiletti RR:

Anti-brain antibodies in PANDAS versus uncomplicated streptococcal

infection. Pediatr Neurol 2004, 30:107�110.

127. Maina G, Albert U, Bogetto F, Borghese C, Berro AC, Mutani R, Rossi F,

Vigliani MC: Anti-brain antibodies in adult patients with obsessivecompulsive

disorder. J Affect Disord 2009, 116:192�200.

128. Brimberg L, Benhar I, Mascaro-Blanco A, Alvarez K, Lotan D, Winter C, Klein J,

Moses AE, Somnier FE, Leckman JF, Swedo SE, Cunningham MW, Joel D:

Behavioral, pharmacological, and immunological abnormalities after

streptococcal exposure: a novel rat model of Sydenham chorea and

related neuropsychiatric disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 2012,

37:2076�2087.

129. Dale RC, Candler PM, Church AJ, Wait R, Pocock JM, Giovannoni G:

Neuronal surface glycolytic enzymes are autoantigen targets in

post-streptococcal autoimmune CNS disease. J Neuroimmunol 2006,

172:187�197.

130. Nicholson TR, Ferdinando S, Krishnaiah RB, Anhoury S, Lennox BR, MataixCols

D, Cleare A, Veale DM, Drummond LM, Fineberg NA, Church AJ,

Giovannoni G, Heyman I: Prevalence of anti-basal ganglia antibodies in

adult obsessive-compulsive disorder: cross-sectional study. Br J Psychiatry

2012, 200:381�386.

131. Wu K, Hanna GL, Rosenberg DR, Arnold PD: The role of glutamate

signaling in the pathogenesis and treatment of obsessive-compulsive

disorder. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2012, 100:726�735.

132. Perlmutter SJ, Leitman SF, Garvey MA, Hamburger S, Feldman E, Leonard

HL, Swedo SE: Therapeutic plasma exchange and intravenous

immunoglobulin for obsessive-compulsive disorder and tic disorders in

childhood. Lancet 1999, 354:1153�1158.

133. Pereira A Jr, Furlan FA: Astrocytes and human cognition: modeling

information integration and modulation of neuronal activity.

Prog Neurobiol 2010, 92:405�420.

134. Barres BA: The mystery and magic of glia: a perspective on their roles in

health and disease. Neuron 2008, 60:430�440.

135. Verkhratsky A, Parpura V, Rodriguez JJ: Where the thoughts dwell: the

physiology of neuronal-glial “diffuse neural net”. Brain Res Rev 2011,

66:133�151.

136. Sofroniew MV: Molecular dissection of reactive astrogliosis and glial scar

formation. Trends Neurosci 2009, 32:638�647.

137. Hamilton NB, Attwell D: Do astrocytes really exocytose neurotransmitters?

Nat Rev Neurosci 2010, 11:227�238.

138. Rajkowska G: Postmortem studies in mood disorders indicate altered

numbers of neurons and glial cells. Biol Psychiatry 2000, 48:766�777.

139. Coupland NJ, Ogilvie CJ, Hegadoren KM, Seres P, Hanstock CC, Allen PS:

Decreased prefrontal Myo-inositol in major depressive disorder.

Biol Psychiatry 2005, 57:1526�1534.

140. Miguel-Hidalgo JJ, Overholser JC, Jurjus GJ, Meltzer HY, Dieter L, Konick L,

Stockmeier CA, Rajkowska G: Vascular and extravascular immunoreactivity

for intercellular adhesion molecule 1 in the orbitofrontal cortex of

subjects with major depression: age-dependent changes. J Affect Disord

2011, 132:422�431.

141. Miguel-Hidalgo JJ, Wei JR, Andrew M, Overholser JC, Jurjus G, Stockmeier

CA, Rajkowska G: Glia pathology in the prefrontal cortex in alcohol

dependence with and without depressive symptoms. Biol Psychiatry 2002,

52:1121�1133.

142. Stockmeier CA, Mahajan GJ, Konick LC, Overholser JC, Jurjus GJ, Meltzer HY,

Uylings HB, Friedman L, Rajkowska G: Cellular changes in the postmortem

hippocampus in major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2004, 56:640�650.

143. Ong�r D, Drevets WC, Price JL: Glial reduction in the subgenual prefrontal

cortex in mood disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998, 95:13290�13295.

144. Gittins RA, Harrison PJ: A morphometric study of glia and neurons in the

anterior cingulate cortex in mood disorder. J Affect Disord 2011,

133:328�332.

145. Cotter D, Mackay D, Beasley C, Kerwin R, Everall I: Reduced glial density

and neuronal volume in major depressive disorder and schizophrenia in

the anterior cingulate cortex [abstract]. Schizophrenia Res 2000, 41:106.

146. Si X, Miguel-Hidalgo JJ, Rajkowska G: GFAP expression is reduced in the

dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in depression. In Society for Neuroscience; 2003.

Neuroscience Meeting Planne: New Orleans; 2003.

147. Legutko B, Mahajan G, Stockmeier CA, Rajkowska G: White matter astrocytes

are reduced in depression. In Society for Neuroscience. Neuroscience Meeting

Planner: Washington, DC; 2011.148. Edgar N, Sibille E: A putative functional role for oligodendrocytes in

mood regulation. Transl Psychiatry 2012, 2:e109.

149. Rajkowska G, Halaris A, Selemon LD: Reductions in neuronal and glial

density characterize the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in bipolar

disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2001, 49:741�752.

150. Cotter D, Mackay D, Chana G, Beasley C, Landau S, Everall IP: Reduced

neuronal size and glial cell density in area 9 of the dorsolateral

prefrontal cortex in subjects with major depressive disorder. Cereb Cortex

2002, 12:386�394.

151. Stark AK, Uylings HB, Sanz-Arigita E, Pakkenberg B: Glial cell loss in the

anterior cingulate cortex, a subregion of the prefrontal cortex, in

subjects with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2004, 161:882�888.

152. Konopaske GT, Dorph-Petersen KA, Sweet RA, Pierri JN, Zhang W, Sampson

AR, Lewis DA: Effect of chronic antipsychotic exposure on astrocyte and

oligodendrocyte numbers in macaque monkeys. Biol Psychiatry 2008,

63:759�765.

153. Selemon LD, Lidow MS, Goldman-Rakic PS: Increased volume and glial

density in primate prefrontal cortex associated with chronic

antipsychotic drug exposure. Biol Psychiatry 1999, 46:161�172.

154. Steiner J, Bernstein HG, Bielau H, Farkas N, Winter J, Dobrowolny H, Brisch R,

Gos T, Mawrin C, Myint AM, Bogerts B: S100B-immunopositive glia is

elevated in paranoid as compared to residual schizophrenia: a

morphometric study. J Psychiatr Res 2008, 42:868�876.

155. Carter CJ: eIF2B and oligodendrocyte survival: where nature and nurture

meet in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia? Schizophr Bull 2007,

33:1343�1353.

156. Hayashi Y, Nihonmatsu-Kikuchi N, Hisanaga S, Yu XJ, Tatebayashi Y:

Neuropathological similarities and differences between schizophrenia

and bipolar disorder: a flow cytometric postmortem brain study.

PLoS One 2012, 7:e33019.

157. Uranova NA, Vikhreva OV, Rachmanova VI, Orlovskaya DD: Ultrastructural

alterations of myelinated fibers and oligodendrocytes in the prefrontal

cortex in schizophrenia: a postmortem morphometric study.

Schizophr Res Treatment 2011, 2011:325789.

158. Torres-Platas SG, Hercher C, Davoli MA, Maussion G, Labonte B, Turecki

G, Mechawar N: Astrocytic hypertrophy in anterior cingulate white

matter of depressed suicides. Neuropsychopharmacology 2011,

36:2650�2658.

159. Pereira A Jr, Furlan FA: On the role of synchrony for neuron-astrocyte

interactions and perceptual conscious processing. J Biol Phys 2009,

35:465�480.

160. Kettenmann H, Hanisch UK, Noda M, Verkhratsky A: Physiology of

microglia. Physiol Rev 2011, 91:461�553.

161. Tremblay ME, Stevens B, Sierra A, Wake H, Bessis A, Nimmerjahn A: The role

of microglia in the healthy brain. J Neurosci 2011, 31:16064�16069.

162. Kaindl AM, Degos V, Peineau S, Gouadon E, Chhor V, Loron G, Le

Charpentier T, Josserand J, Ali C, Vivien D, Collingridge GL, Lombet A, Issa L,

Rene F, Loeffler JP, Kavelaars A, Verney C, Mantz J, Gressens P: Activation of

microglial N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors triggers inflammation and

neuronal cell death in the developing and mature brain. Ann Neurol

2012, 72:536�549.

163. Schwartz M, Shaked I, Fisher J, Mizrahi T, Schori H: Protective

autoimmunity against the enemy within: fighting glutamate toxicity.

Trends Neurosci 2003, 26:297�302.

164. Pacheco R, Gallart T, Lluis C, Franco R: Role of glutamate on T-cell

mediated immunity. J Neuroimmunol 2007, 185:9�19.

165. Najjar S, Pearlman D, Miller DC, Devinsky O: Refractory epilepsy associated

with microglial activation. Neurologist 2011, 17:249�254.

166. Schwartz M, Butovsky O, Bruck W, Hanisch UK: Microglial phenotype: is the

commitment reversible? Trends Neurosci 2006, 29:68�74.

167. Wang F, Wu H, Xu S, Guo X, Yang J, Shen X: Macrophage migration

inhibitory factor activates cyclooxygenase 2-prostaglandin E2 in cultured

spinal microglia. Neurosci Res 2011, 71:210�218.

168. Zhang XY, Xiu MH, Song C, Chenda C, Wu GY, Haile CN, Kosten TA, Kosten

TR: Increased serum S100B in never-medicated and medicated

schizophrenic patients. J Psychiatr Res 2010, 44:1236�1240.

169. Kawasaki Y, Zhang L, Cheng JK, Ji RR: Cytokine mechanisms of central

sensitization: distinct and overlapping role of interleukin-1beta,

interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in regulating synaptic and

neuronal activity in the superficial spinal cord. J Neurosci 2008,

28:5189�5194.

170. M�ller N, Schwarz MJ: The immunological basis of glutamatergic

disturbance in schizophrenia: towards an integrated view. J Neural

Transm Suppl 2007, 72:269�280.

171. Hestad KA, Tonseth S, Stoen CD, Ueland T, Aukrust P: Raised plasma levels

of tumor necrosis factor alpha in patients with depression: normalization

during electroconvulsive therapy. J ECT 2003, 19:183�188.

172. Kubera M, Kenis G, Bosmans E, Zieba A, Dudek D, Nowak G, Maes M:

Plasma levels of interleukin-6, interleukin-10, and interleukin-1 receptor

antagonist in depression: comparison between the acute state and after

remission. Pol J Pharmacol 2000, 52:237�241.

173. Miller BJ, Buckley P, Seabolt W, Mellor A, Kirkpatrick B: Meta-analysis of

cytokine alterations in schizophrenia: clinical status and antipsychotic

effects. Biol Psychiatry 2011, 70:663�671.

174. Potvin S, Stip E, Sepehry AA, Gendron A, Bah R, Kouassi E: Inflammatory

cytokine alterations in schizophrenia: a systematic quantitative review.

Biol Psychiatry 2008, 63:801�808.

175. Reale M, Patruno A, De Lutiis MA, Pesce M, Felaco M, Di Giannantonio M, Di

Nicola M, Grilli A: Dysregulation of chemo-cytokine production in

schizophrenic patients versus healthy controls. BMC Neurosci 2011, 12:13.

176. Fluitman SB, Denys DA, Heijnen CJ, Westenberg HG: Disgust affects TNFalpha,

IL-6 and noradrenalin levels in patients with obsessive-compulsive

disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2010, 35:906�911.

177. Konuk N, Tekin IO, Ozturk U, Atik L, Atasoy N, Bektas S, Erdogan A: Plasma

levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6 in obsessive

compulsive disorder. Mediators Inflamm 2007, 2007:65704.

178. Monteleone P, Catapano F, Fabrazzo M, Tortorella A, Maj M: Decreased

blood levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in patients with obsessivecompulsive

disorder. Neuropsychobiology 1998, 37:182�185.

179. Marazziti D, Presta S, Pfanner C, Gemignani A, Rossi A, Sbrana S, Rocchi V,

Ambrogi F, Cassano GB: Immunological alterations in adult obsessivecompulsive

disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1999, 46:810�814.

180. Zai G, Arnold PD, Burroughs E, Richter MA, Kennedy JL: Tumor necrosis

factor-alpha gene is not associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Psychiatr Genet 2006, 16:43.

181. Rodr�guez AD, Gonz�lez PA, Garc�a MJ, de la Rosa A, Vargas M, Marrero F:

Circadian variations in proinflammatory cytokine concentrations in acute

myocardial infarction. Rev Esp Cardiol 2003, 56:555�560.

182. Oliver JC, Bland LA, Oettinger CW, Arduino MJ, McAllister SK, Aguero SM,

Favero MS: Cytokine kinetics in an in vitro whole blood model following

an endotoxin challenge. Lymphokine Cytokine Res 1993, 12:115�120.

183. Le T, Leung L, Carroll WL, Schibler KR: Regulation of interleukin-10 gene

expression: possible mechanisms accounting for its upregulation and for

maturational differences in its expression by blood mononuclear cells.

Blood 1997, 89:4112�4119.

184. Lee MC, Ting KK, Adams S, Brew BJ, Chung R, Guillemin GJ:

Characterisation of the expression of NMDA receptors in human

astrocytes. PLoS One 2010, 5:e14123.

185. Myint AM, Kim YK, Verkerk R, Scharpe S, Steinbusch H, Leonard B:

Kynurenine pathway in major depression: evidence of impaired

neuroprotection. J Affect Disord 2007, 98:143�151.

186. Sanacora G, Treccani G, Popoli M: Towards a glutamate hypothesis of

depression: an emerging frontier of neuropsychopharmacology for

mood disorders. Neuropharmacology 2012, 62:63�77.

187. Saleh A, Schroeter M, Jonkmanns C, Hartung HP, Modder U, Jander S: In

vivo MRI of brain inflammation in human ischaemic stroke. Brain 2004,

127:1670�1677.

188. Tilleux S, Hermans E: Neuroinflammation and regulation of glial glutamate

uptake in neurological disorders. J Neurosci Res 2007, 85:2059�2070.

189. Helms HC, Madelung R, Waagepetersen HS, Nielsen CU, Brodin B: In vitro

evidence for the brain glutamate efflux hypothesis: brain endothelial

cells cocultured with astrocytes display a polarized brain-to-blood

transport of glutamate. 2012, 60:882�893.

190. Leonard BE: The concept of depression as a dysfunction of the immune

system. Curr Immunol Rev 2010, 6:205�212.

191. Labrie V, Wong AH, Roder JC: Contributions of the D-serine pathway to

schizophrenia. Neuropharmacology 2012, 62:1484�1503.

192. Gras G, Samah B, Hubert A, Leone C, Porcheray F, Rimaniol AC: EAAT

expression by macrophages and microglia: still more questions than

answers. Amino Acids 2012, 42:221�229.

193. Livingstone PD, Dickinson JA, Srinivasan J, Kew JN, Wonnacott S:

Glutamate-dopamine crosstalk in the rat prefrontal cortex is modulated by Alpha7 nicotinic receptors and potentiated by PNU-120596. J Mol

Neurosci 2010, 40:172�176.194. Kondziella D, Brenner E, Eyjolfsson EM, Sonnewald U: How do glialneuronal

interactions fit into current neurotransmitter hypotheses of

schizophrenia? Neurochem Int 2007, 50:291�301.

195. Wu HQ, Pereira EF, Bruno JP, Pellicciari R, Albuquerque EX, Schwarcz R: The

astrocyte-derived alpha7 nicotinic receptor antagonist kynurenic acid

controls extracellular glutamate levels in the prefrontal cortex. J Mol

Neurosci 2010, 40:204�210.

196. Steiner J, Bogerts B, Schroeter ML, Bernstein HG: S100B protein in

neurodegenerative disorders. Clin Chem Lab Med 2011, 49:409�424.

197. Steiner J, Marquardt N, Pauls I, Schiltz K, Rahmoune H, Bahn S, Bogerts B,

Schmidt RE, Jacobs R: Human CD8(+) T cells and NK cells express and

secrete S100B upon stimulation. Brain Behav Immun 2011, 25:1233�1241.

198. Shanmugam N, Kim YS, Lanting L, Natarajan R: Regulation of

cyclooxygenase-2 expression in monocytes by ligation of the receptor

for advanced glycation end products. J Biol Chem 2003, 278:34834�34844.

199. Rothermundt M, Ohrmann P, Abel S, Siegmund A, Pedersen A, Ponath G,

Suslow T, Peters M, Kaestner F, Heindel W, Arolt V, Pfleiderer B: Glial cell

activation in a subgroup of patients with schizophrenia indicated by

increased S100B serum concentrations and elevated myo-inositol.

Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2007, 31:361�364.

200. Falcone T, Fazio V, Lee C, Simon B, Franco K, Marchi N, Janigro D: Serum

S100B: a potential biomarker for suicidality in adolescents? PLoS One

2010, 5:e11089.

201. Schroeter ML, Abdul-Khaliq H, Krebs M, Diefenbacher A, Blasig IE: Serum

markers support disease-specific glial pathology in major depression.

J Affect Disord 2008, 111:271�280.

202. Rothermundt M, Ahn JN, Jorgens S: S100B in schizophrenia: an update.

Gen Physiol Biophys 2009, 28 Spec No Focus:F76�F81.

203. Schroeter ML, Abdul-Khaliq H, Krebs M, Diefenbacher A, Blasig IE: Neuronspecific

enolase is unaltered whereas S100B is elevated in serum of

patients with schizophrenia�original research and meta-analysis.

Psychiatry Res 2009, 167:66�72.

204. Rothermundt M, Missler U, Arolt V, Peters M, Leadbeater J, Wiesmann M,

Rudolf S, Wandinger KP, Kirchner H: Increased S100B blood levels in

unmedicated and treated schizophrenic patients are correlated with

negative symptomatology. Mol Psychiatry 2001, 6:445�449.

205. Suchankova P, Klang J, Cavanna C, Holm G, Nilsson S, Jonsson EG, Ekman A:

Is the Gly82Ser polymorphism in the RAGE gene relevant to

schizophrenia and the personality trait psychoticism? J Psychiatry Neurosci

2012, 37:122�128.

206. Scapagnini G, Davinelli S, Drago F, De Lorenzo A, Oriani G: Antioxidants as

antidepressants: fact or fiction? CNS Drugs 2012, 26:477�490.

207. Ng F, Berk M, Dean O, Bush AI: Oxidative stress in psychiatric disorders:

evidence base and therapeutic implications. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol

2008, 11:851�876.

208. Salim S, Chugh G, Asghar M: Inflammation in anxiety. Adv Protein Chem

Struct Biol 2012, 88:1�25.

209. Anderson G, Berk M, Dodd S, Bechter K, Altamura AC, Dell’osso B, Kanba S,

Monji A, Fatemi SH, Buckley P, Debnath M, Das UN, Meyer U, M�ller N,

Kanchanatawan B, Maes M: Immuno-inflammatory, oxidative and nitrosative

stress, and neuroprogressive pathways in the etiology, course and treatment

of schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2013, 42:1�42.

210. Coughlin JM, Ishizuka K, Kano SI, Edwards JA, Seifuddin FT, Shimano MA,

Daley EL, et al: Marked reduction of soluble superoxide dismutase-1

(SOD1) in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with recent-onset

schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 2012, 18:10�11.

211. Bombaci M, Grifantini R, Mora M, Reguzzi V, Petracca R, Meoni E, Balloni S,

Zingaretti C, Falugi F, Manetti AG, Margarit I, Musser JM, Cardona F, Orefici

G, Grandi G, Bensi G: Protein array profiling of tic patient sera reveals a

broad range and enhanced immune response against Group A

Streptococcus antigens. PLoS One 2009, 4:e6332.

212. Valerio A, Cardile A, Cozzi V, Bracale R, Tedesco L, Pisconti A, Palomba L,

Cantoni O, Clementi E, Moncada S, Carruba MO, Nisoli E: TNF-alpha

downregulates eNOS expression and mitochondrial biogenesis in fat

and muscle of obese rodents. J Clin Invest 2006, 116:2791�2798.

213. Ott M, Gogvadze V, Orrenius S, Zhivotovsky B: Mitochondria, oxidative

stress and cell death. Apoptosis 2007, 12:913�922.

214. Shalev H, Serlin Y, Friedman A: Breaching the blood�brain barrier as a gate

to psychiatric disorder. Cardiovasc Psychiatry Neurol 2009, 2009:278531.

215. Abbott NJ, Ronnback L, Hansson E: Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the

blood�brain barrier. Nat Rev Neurosci 2006, 7:41�53.

216. Bechter K, Reiber H, Herzog S, Fuchs D, Tumani H, Maxeiner HG:

Cerebrospinal fluid analysis in affective and schizophrenic spectrum

disorders: identification of subgroups with immune responses and

blood-CSF barrier dysfunction. J Psychiatr Res 2010, 44:321�330.

217. Harris LW, Wayland M, Lan M, Ryan M, Giger T, Lockstone H, Wuethrich I,

Mimmack M, Wang L, Kotter M, Craddock R, Bahn S: The cerebral

microvasculature in schizophrenia: a laser capture microdissection study.

PLoS One 2008, 3:e3964.

218. Lin JJ, Mula M, Hermann BP: Uncovering the neurobehavioural

comorbidities of epilepsy over the lifespan. Lancet 2012, 380:1180�1192.

219. Isingrini E, Belzung C, Freslon JL, Machet MC, Camus V: Fluoxetine effect on

aortic nitric oxide-dependent vasorelaxation in the unpredictable

chronic mild stress model of depression in mice. Psychosom Med 2012,

74:63�72.

220. Zhang XY, Zhou DF, Cao LY, Zhang PY, Wu GY, Shen YC: The effect of

risperidone treatment on superoxide dismutase in schizophrenia. J Clin

Psychopharmacol 2003, 23:128�131.

221. Lavoie KL, Pelletier R, Arsenault A, Dupuis J, Bacon SL: Association between

clinical depression and endothelial function measured by forearm

hyperemic reactivity. Psychosom Med 2010, 72:20�26.

222. Chrapko W, Jurasz P, Radomski MW, Archer SL, Newman SC, Baker G, Lara N,

Le Melledo JM: Alteration of decreased plasma NO metabolites and

platelet NO synthase activity by paroxetine in depressed patients.

Neuropsychopharmacology 2006, 31:1286�1293.

223. Chrapko WE, Jurasz P, Radomski MW, Lara N, Archer SL, Le Melledo JM:

Decreased platelet nitric oxide synthase activity and plasma nitric oxide

metabolites in major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2004, 56:129�134.

224. Stuehr DJ, Santolini J, Wang ZQ, Wei CC, Adak S: Update on mechanism

and catalytic regulation in the NO synthases. J Biol Chem 2004,

279:36167�36170.

225. Chen W, Druhan LJ, Chen CA, Hemann C, Chen YR, Berka V, Tsai AL, Zweier

JL: Peroxynitrite induces destruction of the tetrahydrobiopterin and

heme in endothelial nitric oxide synthase: transition from reversible to

irreversible enzyme inhibition. Biochemistry 2010, 49:3129�3137.

226. Chen CA, Wang TY, Varadharaj S, Reyes LA, Hemann C, Talukder MA, Chen

YR, Druhan LJ, Zweier JL: S-glutathionylation uncouples eNOS and

regulates its cellular and vascular function. Nature 2010, 468:1115�1118.

227. Szabo C, Ischiropoulos H, Radi R: Peroxynitrite: biochemistry,

pathophysiology and development of therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov

2007, 6:662�680.

228. Papakostas GI, Shelton RC, Zajecka JM, Etemad B, Rickels K, Clain A, Baer L,

Dalton ED, Sacco GR, Schoenfeld D, Pencina M, Meisner A, Bottiglieri T,

Nelson E, Mischoulon D, Alpert JE, Barbee JG, Zisook S, Fava M: Lmethylfolate

as adjunctive therapy for SSRI-resistant major depression:

results of two randomized, double-blind, parallel-sequential trials. Am J

Psychiatry 2012, 169:1267�1274.

229. Antoniades C, Shirodaria C, Warrick N, Cai S, de Bono J, Lee J, Leeson P,

Neubauer S, Ratnatunga C, Pillai R, Refsum H, Channon KM: 5-

methyltetrahydrofolate rapidly improves endothelial function and

decreases superoxide production in human vessels: effects on vascular

tetrahydrobiopterin availability and endothelial nitric oxide synthase

coupling. Circulation 2006, 114:1193�1201.

230. Masano T, Kawashima S, Toh R, Satomi-Kobayashi S, Shinohara M, Takaya T,

Sasaki N, Takeda M, Tawa H, Yamashita T, Yokoyama M, Hirata K: Beneficial

effects of exogenous tetrahydrobiopterin on left ventricular remodeling

after myocardial infarction in rats: the possible role of oxidative stress

caused by uncoupled endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circ J 2008,

72:1512�1519.

231. Alp NJ, Channon KM: Regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by

tetrahydrobiopterin in vascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2004,

24:413�420.

232. Szymanski S, Ashtari M, Zito J, Degreef G, Bogerts B, Lieberman J:

Gadolinium-DTPA enhanced gradient echo magnetic resonance scans in

first episode of psychosis and chronic schizophrenic patients.

Psychiatry Res 1991, 40:203�207.

233. Butler T, Weisholtz D, Isenberg N, Harding E, Epstein J, Stern E, Silbersweig

D: Neuroimaging of frontal-limbic dysfunction in schizophrenia and

epilepsy-related psychosis: toward a convergent neurobiology.

Epilepsy Behav 2012, 23:113�122.234. Butler T, Maoz A, Vallabhajosula S, Moeller J, Ichise M, Paresh K, Pervez F,

Friedman D, Goldsmith S, Najjar S, Osborne J, Solnes L, Wang X, French J,

Thesen T, Devinsky O, Kuzniecky R, Stern E, Silbersweig D: Imaging

inflammation in a patient with epilepsy associated with antibodies to

glutamic acid decarboxylase [abstract]. In Am Epilepsy Society Abstracts,

Volume 2. Baltimore: American Epilepsy Society; 2011:191.

235. van Berckel BN, Bossong MG, Boellaard R, Kloet R, Schuitemaker A, Caspers

E, Luurtsema G, Windhorst AD, Cahn W, Lammertsma AA, Kahn RS:

Microglia activation in recent-onset schizophrenia: a quantitative (R)-

[11C]PK11195 positron emission tomography study. Biol Psychiatry 2008,

64:820�822.

236. Doorduin J, de Vries EF, Willemsen AT, de Groot JC, Dierckx RA, Klein HC:

Neuroinflammation in schizophrenia-related psychosis: a PET study.

J Nucl Med 2009, 50:1801�1807.

237. Takano A, Arakawa R, Ito H, Tateno A, Takahashi H, Matsumoto R, Okubo Y,

Suhara T: Peripheral benzodiazepine receptors in patients with chronic

schizophrenia: a PET study with [11C]DAA1106. Int J

Neuropsychopharmacol 2010, 13:943�950.

238. M�ller N, Schwarz MJ, Dehning S, Douhe A, Cerovecki A, Goldstein-Muller B,

Spellmann I, Hetzel G, Maino K, Kleindienst N, M�ller HJ, Arolt V, Riedel M:

The cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor celecoxib has therapeutic effects in

major depression: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo

controlled, add-on pilot study to reboxetine. Mol Psychiatry 2006,

11:680�684.

239. Akhondzadeh S, Jafari S, Raisi F, Nasehi AA, Ghoreishi A, Salehi B, MohebbiRasa

S, Raznahan M, Kamalipour A: Clinical trial of adjunctive celecoxib

treatment in patients with major depression: a double blind and

placebo controlled trial. Depress Anxiety 2009, 26:607�611.

240. Mendlewicz J, Kriwin P, Oswald P, Souery D, Alboni S, Brunello N:

Shortened onset of action of antidepressants in major depression using

acetylsalicylic acid augmentation: a pilot open-label study. Int Clin

Psychopharmacol 2006, 21:227�231.

241. Uher R, Carver S, Power RA, Mors O, Maier W, Rietschel M, Hauser J,

Dernovsek MZ, Henigsberg N, Souery D, Placentino A, Farmer A, McGuffin P:

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and efficacy of antidepressants in

major depressive disorder. Psychol Med 2012, 42:2027�2035.

242. M�ller N, Riedel M, Scheppach C, Brandstatter B, Sokullu S, Krampe K,

Ulmschneider M, Engel RR, Moller HJ, Schwarz MJ: Beneficial antipsychotic

effects of celecoxib add-on therapy compared to risperidone alone in

schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2002, 159:1029�1034.

243. M�ller N, Riedel M, Schwarz MJ, Engel RR: Clinical effects of COX-2

inhibitors on cognition in schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci

2005, 255:149�151.

244. M�ller N, Krause D, Dehning S, Musil R, Schennach-Wolff R, Obermeier M,

Moller HJ, Klauss V, Schwarz MJ, Riedel M: Celecoxib treatment in an early

stage of schizophrenia: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled

trial of celecoxib augmentation of amisulpride treatment.

Schizophr Res 2010, 121:118�124.

245. Sayyah M, Boostani H, Pakseresht S, Malayeri A: A preliminary randomized

double-blind clinical trial on the efficacy of celecoxib as an adjunct in

the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res 2011,

189:403�406.

246. Sublette ME, Ellis SP, Geant AL, Mann JJ: Meta-analysis of the effects of

eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) in clinical trials in depression. J Clin

Psychiatry 2011, 72:1577�1584.

247. Bloch MH, Hannestad J: Omega-3 fatty acids for the treatment of

depression: systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry 2012,

17:1272�1282.

248. Keller WR, Kum LM, Wehring HJ, Koola MM, Buchanan RW, Kelly DL: A

review of anti-inflammatory agents for symptoms of schizophrenia.

J Psychopharmacol.

249. Warner-Schmidt JL, Vanover KE, Chen EY, Marshall JJ, Greengard P:

Antidepressant effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

are attenuated by antiinflammatory drugs in mice and humans. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA 2011, 108:9262�9267.

250. Gallagher PJ, Castro V, Fava M, Weilburg JB, Murphy SN, Gainer VS, Churchill

SE, Kohane IS, Iosifescu DV, Smoller JW, Perlis RH: Antidepressant response

in patients with major depression exposed to NSAIDs: a

pharmacovigilance study. Am J Psychiatry 2012, 169:1065�1072.

251. Shelton RC: Does concomitant use of NSAIDs reduce the effectiveness of

antidepressants? Am J Psychiatry 2012, 169:1012�1015.

252. Martinez-Gras I, Perez-Nievas BG, Garcia-Bueno B, Madrigal JL, AndresEsteban

E, Rodriguez-Jimenez R, Hoenicka J, Palomo T, Rubio G, Leza JC:

The anti-inflammatory prostaglandin 15d-PGJ2 and its nuclear receptor

PPARgamma are decreased in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2011,

128:15�22.

253. Garcia-Bueno B, Perez-Nievas BG, Leza JC: Is there a role for the nuclear

receptor PPARgamma in neuropsychiatric diseases? Int J

Neuropsychopharmacol 2010, 13:1411�1429.

254. Meyer U: Anti-inflammatory signaling in schizophrenia. Brain Behav

Immun 2011, 25:1507�1518.

255. Ramer R, Heinemann K, Merkord J, Rohde H, Salamon A, Linnebacher M,

Hinz B: COX-2 and PPAR-gamma confer cannabidiol-induced apoptosis

of human lung cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther 2013, 12:69�82.

256. Henry CJ, Huang Y, Wynne A, Hanke M, Himler J, Bailey MT, Sheridan JF,

Godbout JP: Minocycline attenuates lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced

neuroinflammation, sickness behavior, and anhedonia.

J Neuroinflammation 2008, 5:15.

257. Sarris J, Mischoulon D, Schweitzer I: Omega-3 for bipolar disorder: metaanalyses

of use in mania and bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2012,

73:81�86.

258. Amminger GP, Schafer MR, Papageorgiou K, Klier CM, Cotton SM, Harrigan

SM, Mackinnon A, McGorry PD, Berger GE: Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids

for indicated prevention of psychotic disorders: a randomized, placebocontrolled

trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010, 67:146�154.

259. Fusar-Poli P, Berger G: Eicosapentaenoic acid interventions in

schizophrenia: meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled studies.

J Clin Psychopharmacol 2012, 32:179�185.

260. Zorumski CF, Paul SM, Izumi Y, Covey DF, Mennerick S: Neurosteroids,

stress and depression: Potential therapeutic opportunities.

Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2013, 37:109�122.

261. Uhde TW, Singareddy R: Biological Research in Anxiety Disorders. In

Psychiatry as a Neuroscience. Edited by Juan Jose L-I, Wolfgang G, Mario M,

Norman S. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2002:237�286.

262. Gibson SA, Korado Z, Shelton RC: Oxidative stress and glutathione

response in tissue cultures from persons with major depression.

J Psychiatr Res 2012, 46:1326�1332.

263. Nery FG, Monkul ES, Hatch JP, Fonseca M, Zunta-Soares GB, Frey BN,

Bowden CL, Soares JC: Celecoxib as an adjunct in the treatment of

depressive or mixed episodes of bipolar disorder: a double-blind,

randomized, placebo-controlled study. 2008, 23:87�94.

264. Levine J, Cholestoy A, Zimmerman J: Possible antidepressant effect of

minocycline. 1996, 153:582.

265. Levkovitz Y, Mendlovich S, Riwkes S, Braw Y, Levkovitch-Verbin H, Gal G,

Fennig S, Treves I, Kron S: A double-blind, randomized study of

minocycline for the treatment of negative and cognitive symptoms in

early-phase schizohprenia. J Clin Psychiatry 2010, 71:138�149.

266. Miyaoka T, Yasukawa R, Yasuda H, Hayashida M, Inagaki T, Horiguchi J:

Possible antipsychotic effect of minocycline in patients with

schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2007, 31:304�307.

267. Miyaoka J, Yasukawa R, Yasuda H, Hayashida M, Inagaki T, Horiguchi J:

Minocycline as adjunctive therapy for schizophrenia: an open-label

study. 2008, 31:287�292.

268. Rodriguez CI, Bender J Jr, Marcus SM, Snape M, Rynn M, Simpson HB:

Minocycline augmentation of pharmacotherapy in obsessive-compulsive

disorder: an open-label trial. 2010, 71:1247�1249.

doi:10.1186/1742-2094-10-43

Cite this article as: Najjar et al.: Neuroinflammation and psychiatric

illness. Journal of Neuroinflammation 2013 10:43.

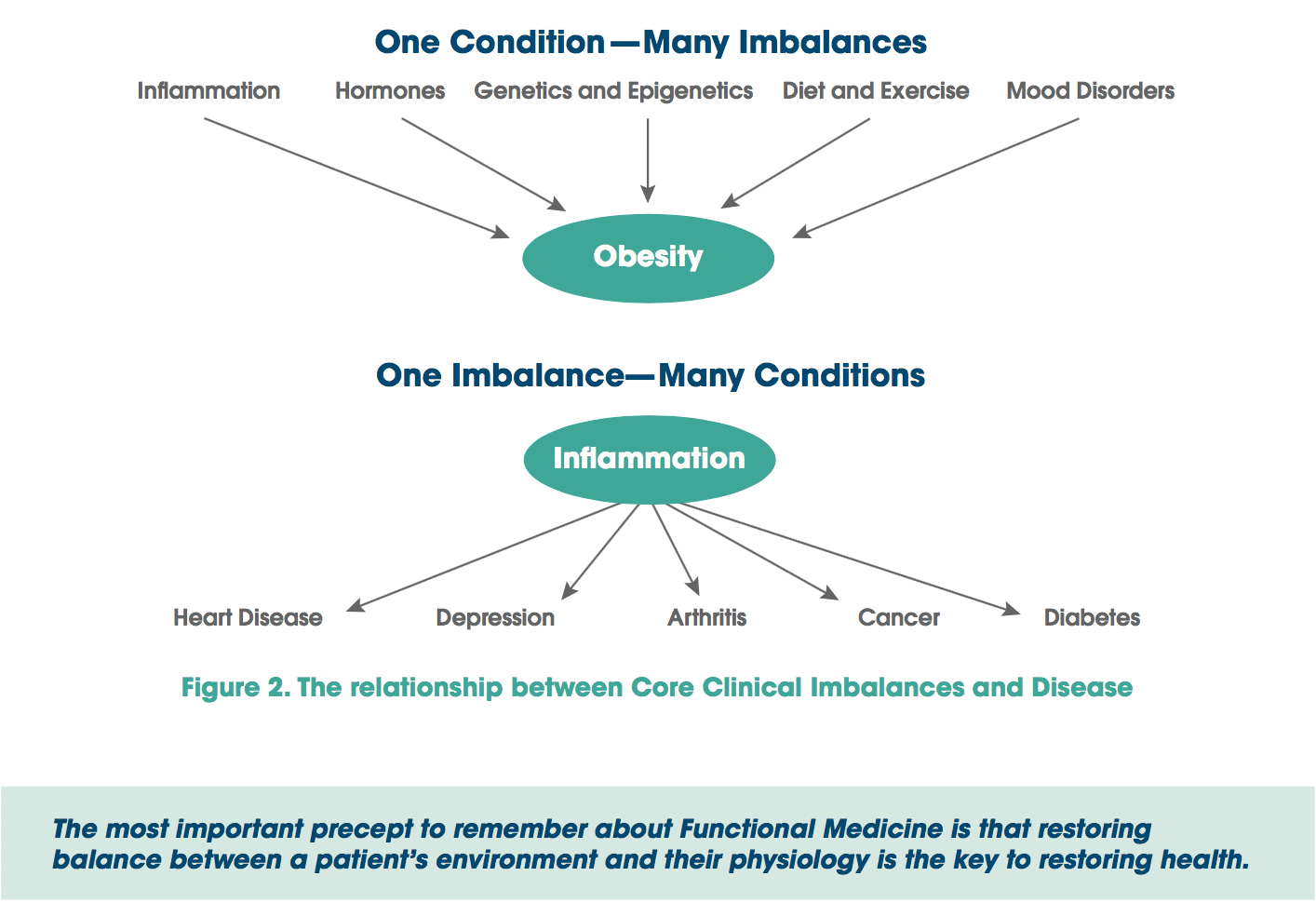

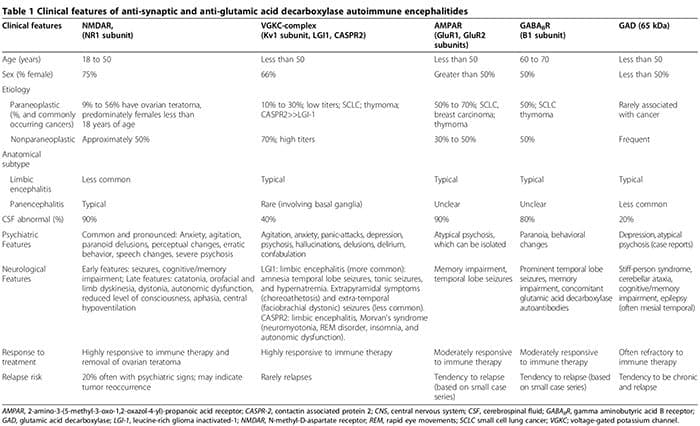

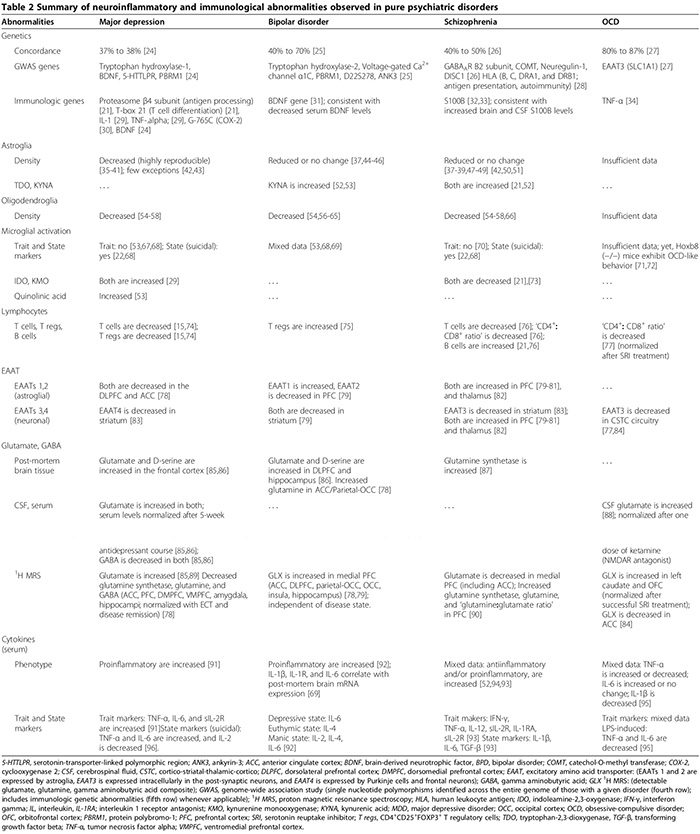

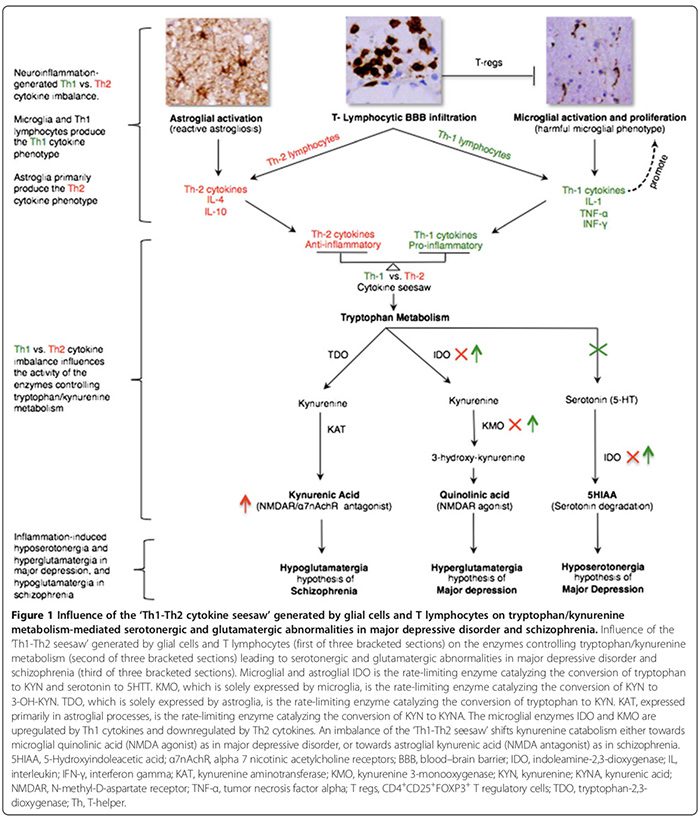

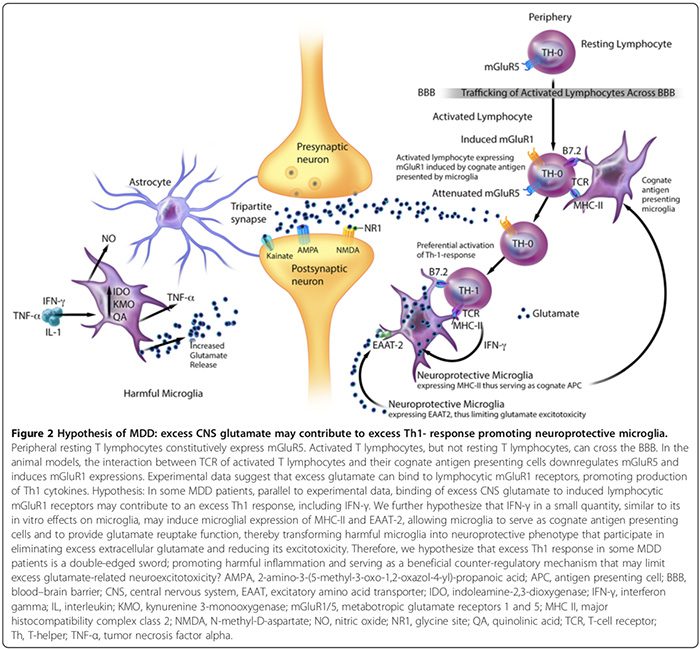

We first review the association between autoimmunity and neuropsychiatric disorders, including: 1) systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) as a prototype of systemic auto- immune disease; 2) autoimmune encephalitides associated with serum anti-synaptic and glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) autoantibodies; and 3) pediatric neuropsychiatric autoimmune disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS) and pure obsessive-compulsive dis- order (OCD) associated with anti-basal ganglia/thalamic autoantibodies. We then discuss the role of innate inflammation/autoimmunity in classical psychiatric disorders, including MDD, bipolar disorder (BPD), schizophrenia, and OCD.

We first review the association between autoimmunity and neuropsychiatric disorders, including: 1) systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) as a prototype of systemic auto- immune disease; 2) autoimmune encephalitides associated with serum anti-synaptic and glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) autoantibodies; and 3) pediatric neuropsychiatric autoimmune disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS) and pure obsessive-compulsive dis- order (OCD) associated with anti-basal ganglia/thalamic autoantibodies. We then discuss the role of innate inflammation/autoimmunity in classical psychiatric disorders, including MDD, bipolar disorder (BPD), schizophrenia, and OCD.

Astroglial & Oligodendroglial Histopathology

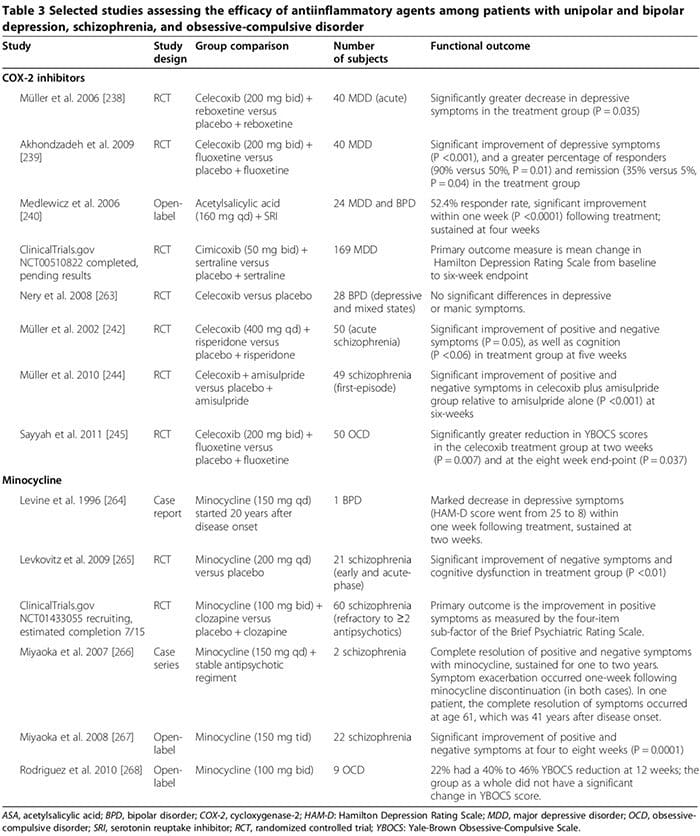

Astroglial & Oligodendroglial Histopathology Several human studies showed that COX-2 inhibitors could ameliorate psychiatric symptoms of MDD, BPD, schizophrenia and OCD (Table 3) [248]. By contrast, adjunctive treatment with non-selective COX-inhibitors (that is, non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)) may reduce the efficacy of SSRIs [249,250]; two large trials reported that exposure to NSAIDs (but not to either selective COX-2 inhibitors or salicylates) was associated with a significant worsening of depression among a sub- set of study participants [249,250].

Several human studies showed that COX-2 inhibitors could ameliorate psychiatric symptoms of MDD, BPD, schizophrenia and OCD (Table 3) [248]. By contrast, adjunctive treatment with non-selective COX-inhibitors (that is, non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)) may reduce the efficacy of SSRIs [249,250]; two large trials reported that exposure to NSAIDs (but not to either selective COX-2 inhibitors or salicylates) was associated with a significant worsening of depression among a sub- set of study participants [249,250].

Allostasis: The process of achieving stability, or homeostasis, through physiological or behavioral change. This can be carried out by means of alteration in HPATG axis hormones, the autonomic nervous system, cytokines, or a number of other systems, and is generally adaptive in the short term. It is essential in order to maintain internal viability amid changing conditions.

Allostasis: The process of achieving stability, or homeostasis, through physiological or behavioral change. This can be carried out by means of alteration in HPATG axis hormones, the autonomic nervous system, cytokines, or a number of other systems, and is generally adaptive in the short term. It is essential in order to maintain internal viability amid changing conditions.

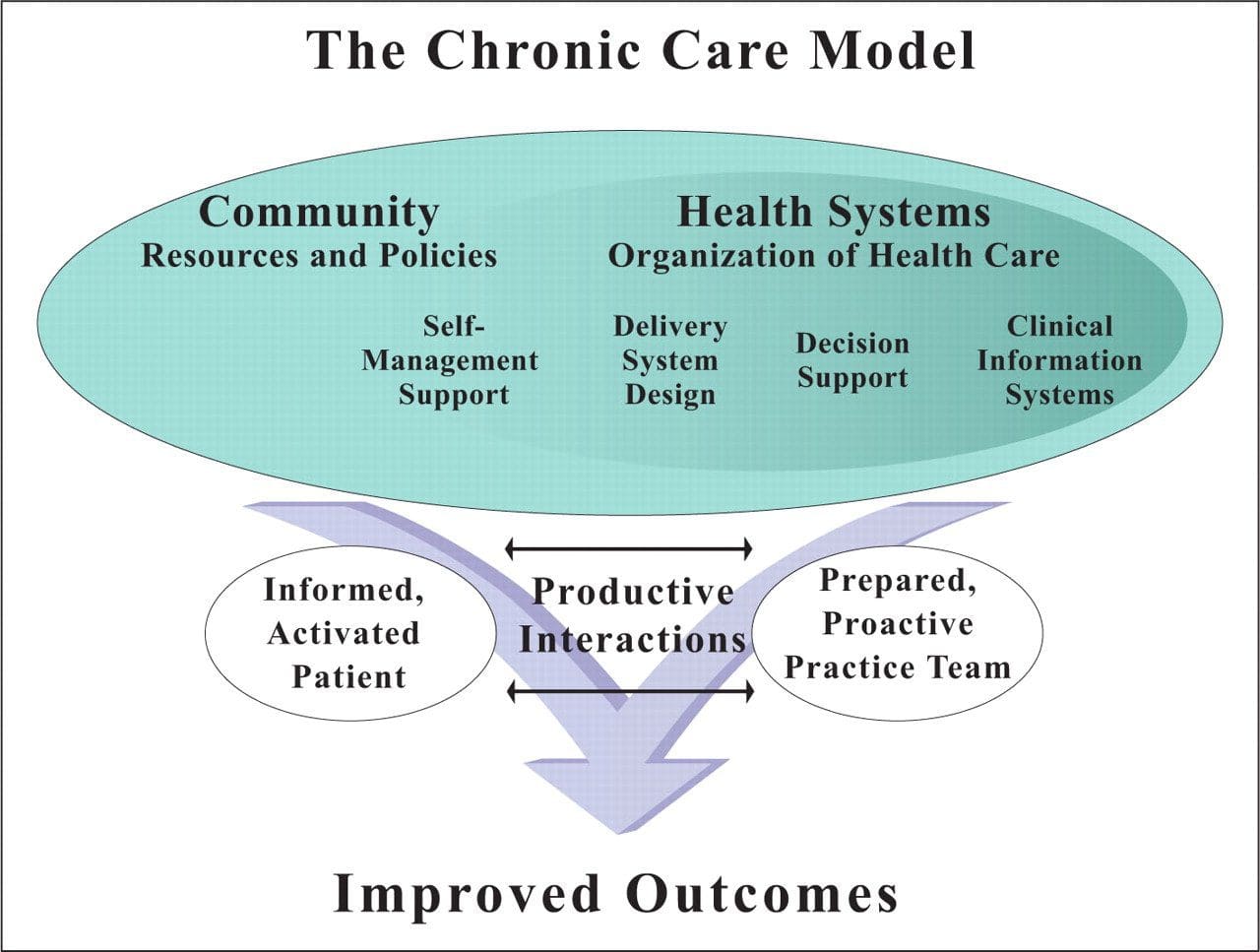

Chronic Care Model: Developed by Wagner and colleagues, the primary focus of this model is to include the essential elements of a healthcare system that encourage high-quality chronic disease care. Such elements include the community, the health system, self-management support, delivery system design, decision support and clinical information systems. It is a response to powerful evidence that patients with chronic conditions often do not obtain the care they need, and that the healthcare system is not currently structured to facilitate such care.�

Chronic Care Model: Developed by Wagner and colleagues, the primary focus of this model is to include the essential elements of a healthcare system that encourage high-quality chronic disease care. Such elements include the community, the health system, self-management support, delivery system design, decision support and clinical information systems. It is a response to powerful evidence that patients with chronic conditions often do not obtain the care they need, and that the healthcare system is not currently structured to facilitate such care.� Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM): A group of diverse medical and healthcare systems, practices, and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional, mainstream medicine. The list of what is considered to be CAM changes frequently, as therapies demonstrated to be safe and effective are adopted by conventional practitioners, and as new approaches to health care emerge. Complementary medicine is used with conventional medicine, not as a substitute for it. Alternative medicine is used in place of conventional medicine.

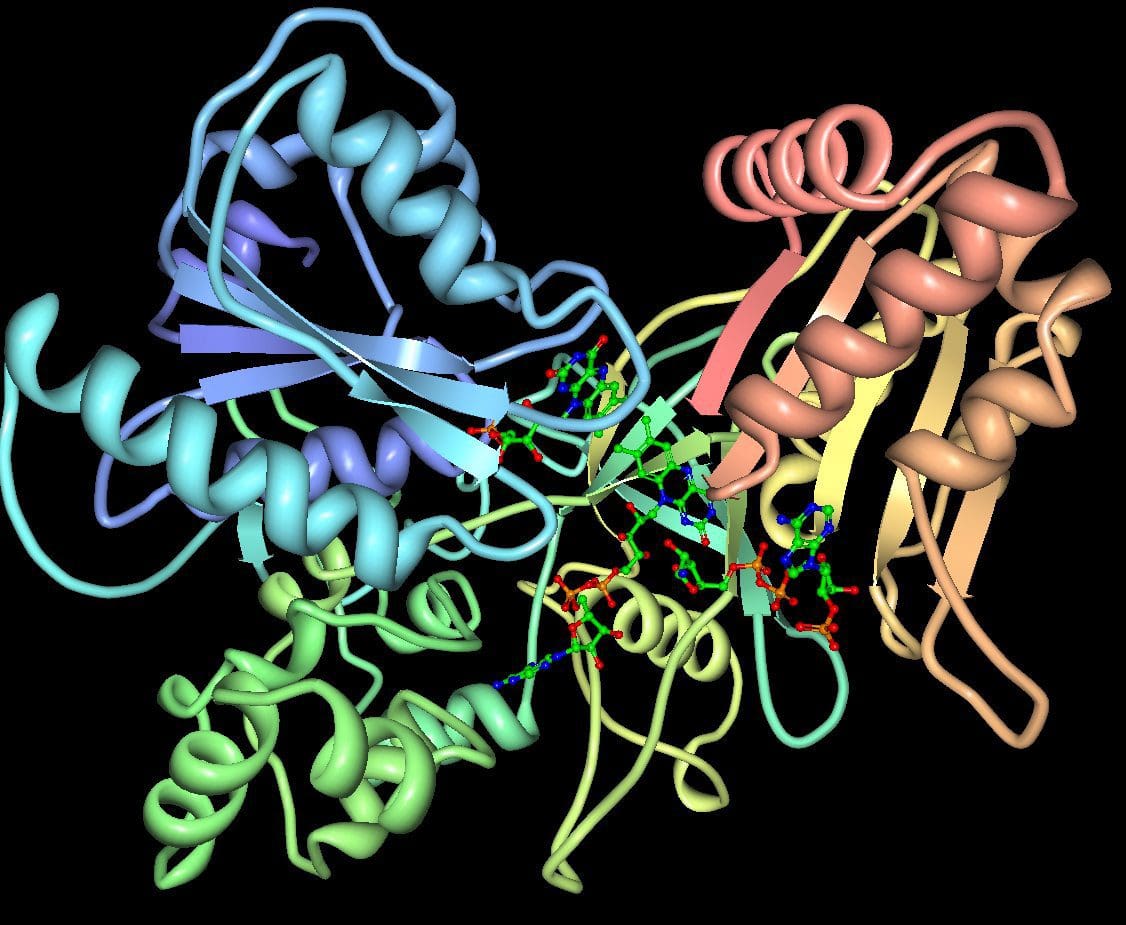

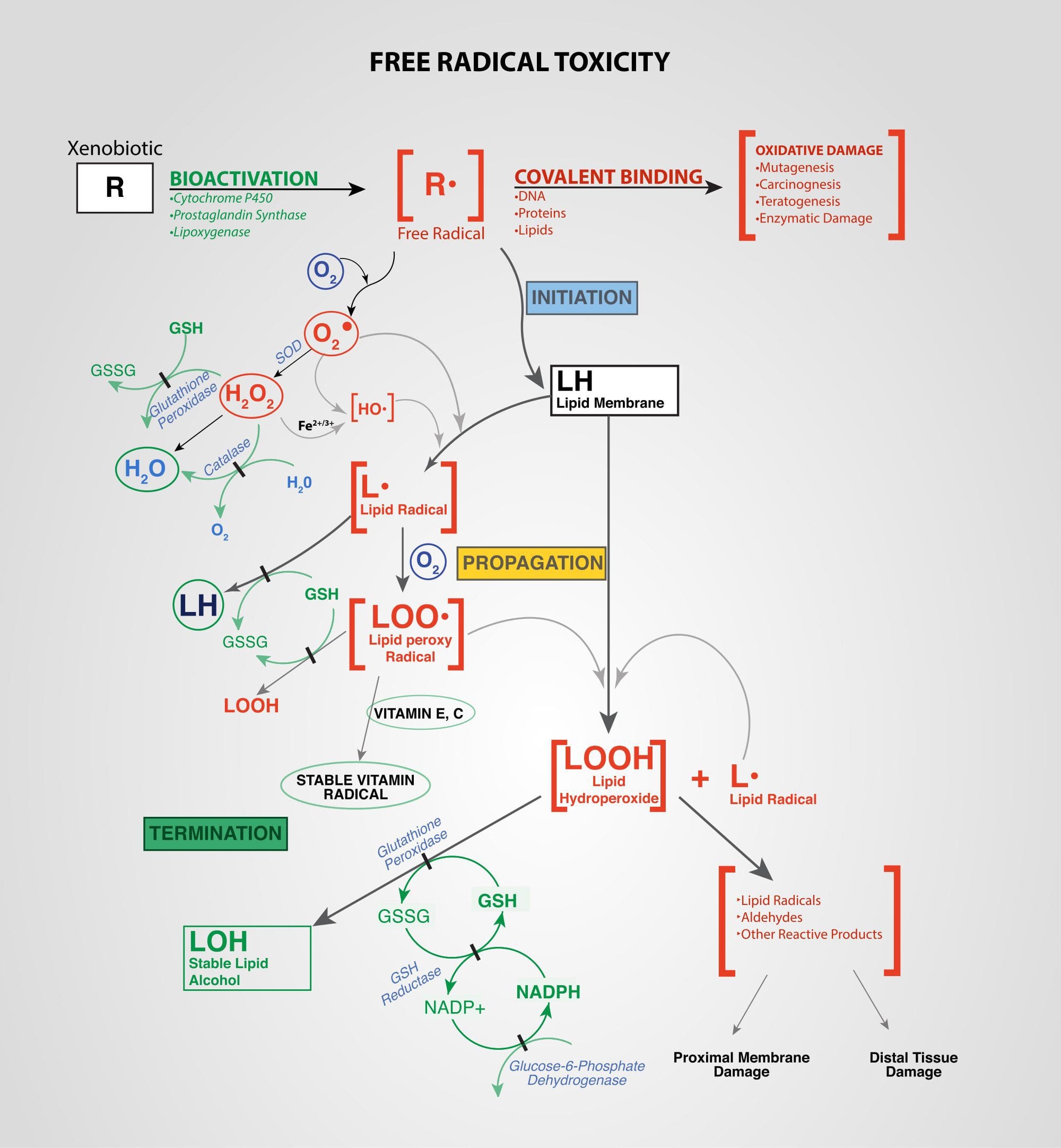

Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM): A group of diverse medical and healthcare systems, practices, and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional, mainstream medicine. The list of what is considered to be CAM changes frequently, as therapies demonstrated to be safe and effective are adopted by conventional practitioners, and as new approaches to health care emerge. Complementary medicine is used with conventional medicine, not as a substitute for it. Alternative medicine is used in place of conventional medicine.  Cytochromes P450 (CYP 450): A large and diverse group of enzymes, most of which function to catalyze the oxidation of organic substances. They are located either in the inner membrane of mitochondria or in the endoplasmic reticulum of cells ans play a critical role in the detoxification of endogenous and exogenous toxins. The substrates of CYP enzymes include metabolic intermediates such as lipids, steroidal hormones, and xenobiotic substances such as drugs.

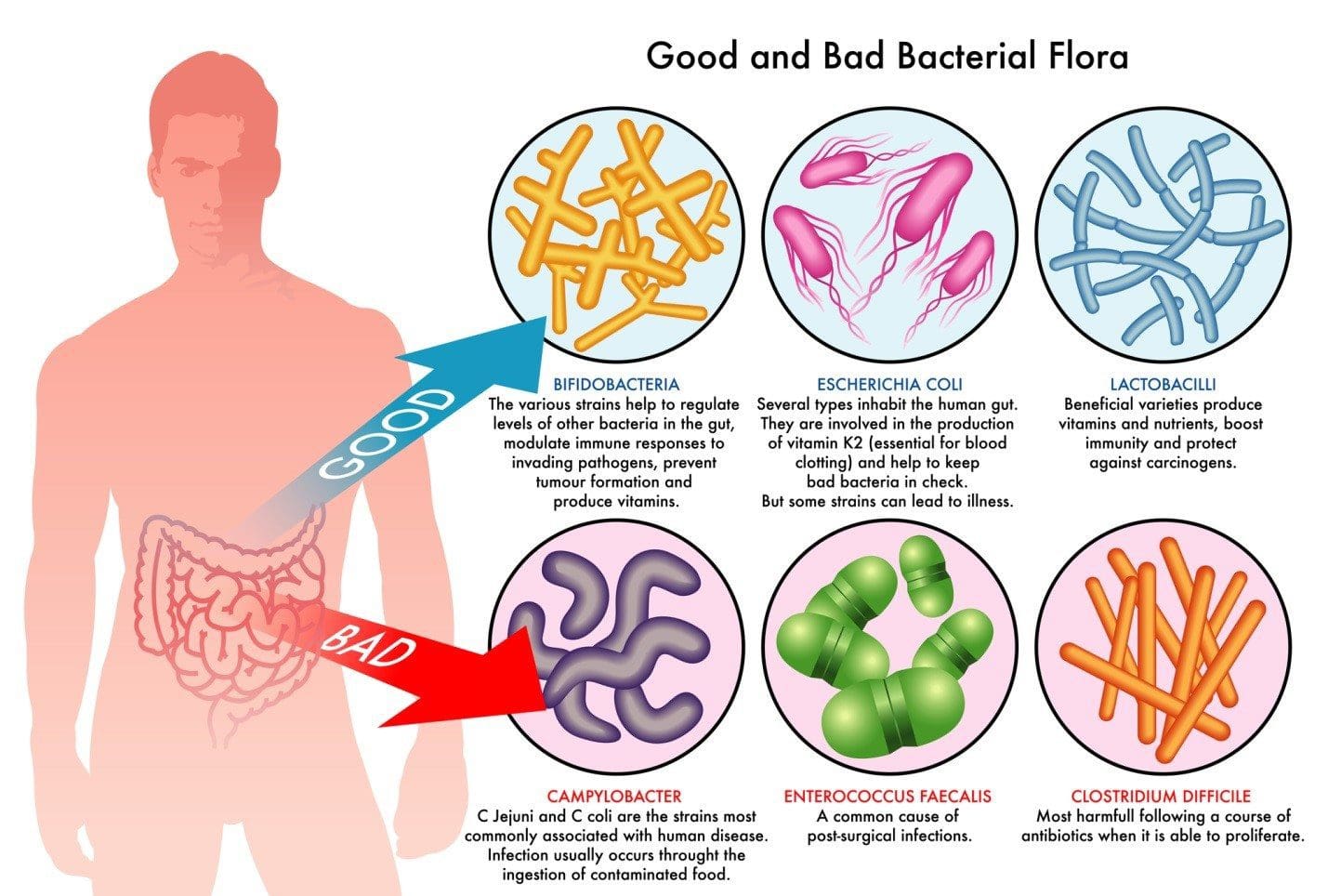

Cytochromes P450 (CYP 450): A large and diverse group of enzymes, most of which function to catalyze the oxidation of organic substances. They are located either in the inner membrane of mitochondria or in the endoplasmic reticulum of cells ans play a critical role in the detoxification of endogenous and exogenous toxins. The substrates of CYP enzymes include metabolic intermediates such as lipids, steroidal hormones, and xenobiotic substances such as drugs. Dysbiosis: A condition that occurs when the normal symbiosis between gut flora and the host is disturbed and organisms of low intrinsic virulence, which normally coexist peacefully with the host, may promote illness. It is distinct from gastrointestinal infection, in which a highly virulent organism gains access to the gastrointestinal tract and infects the host.�

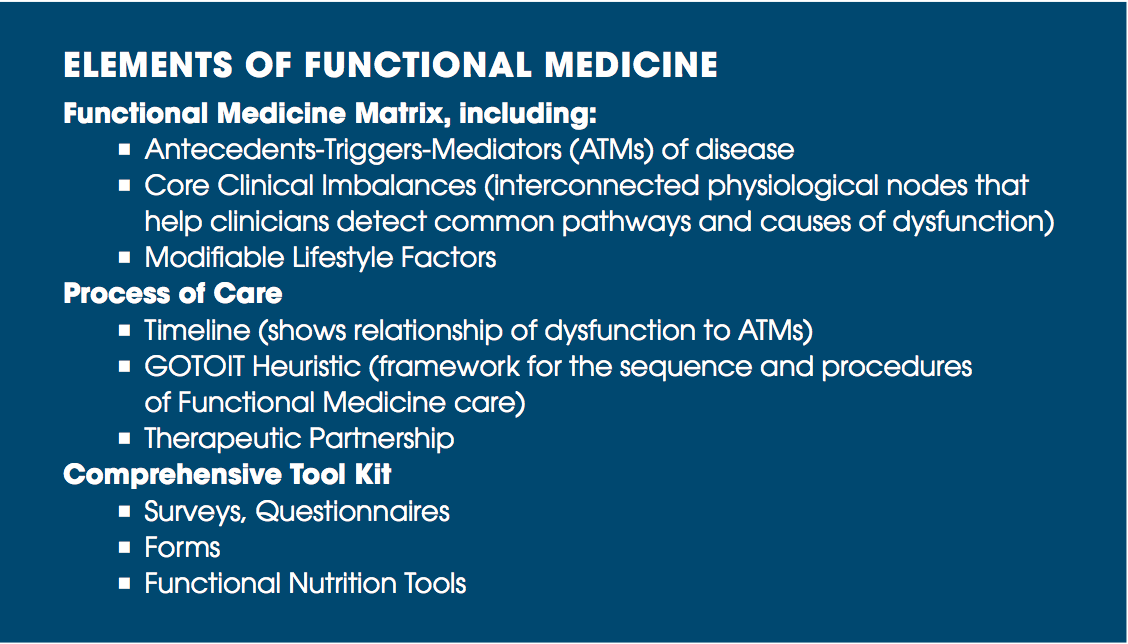

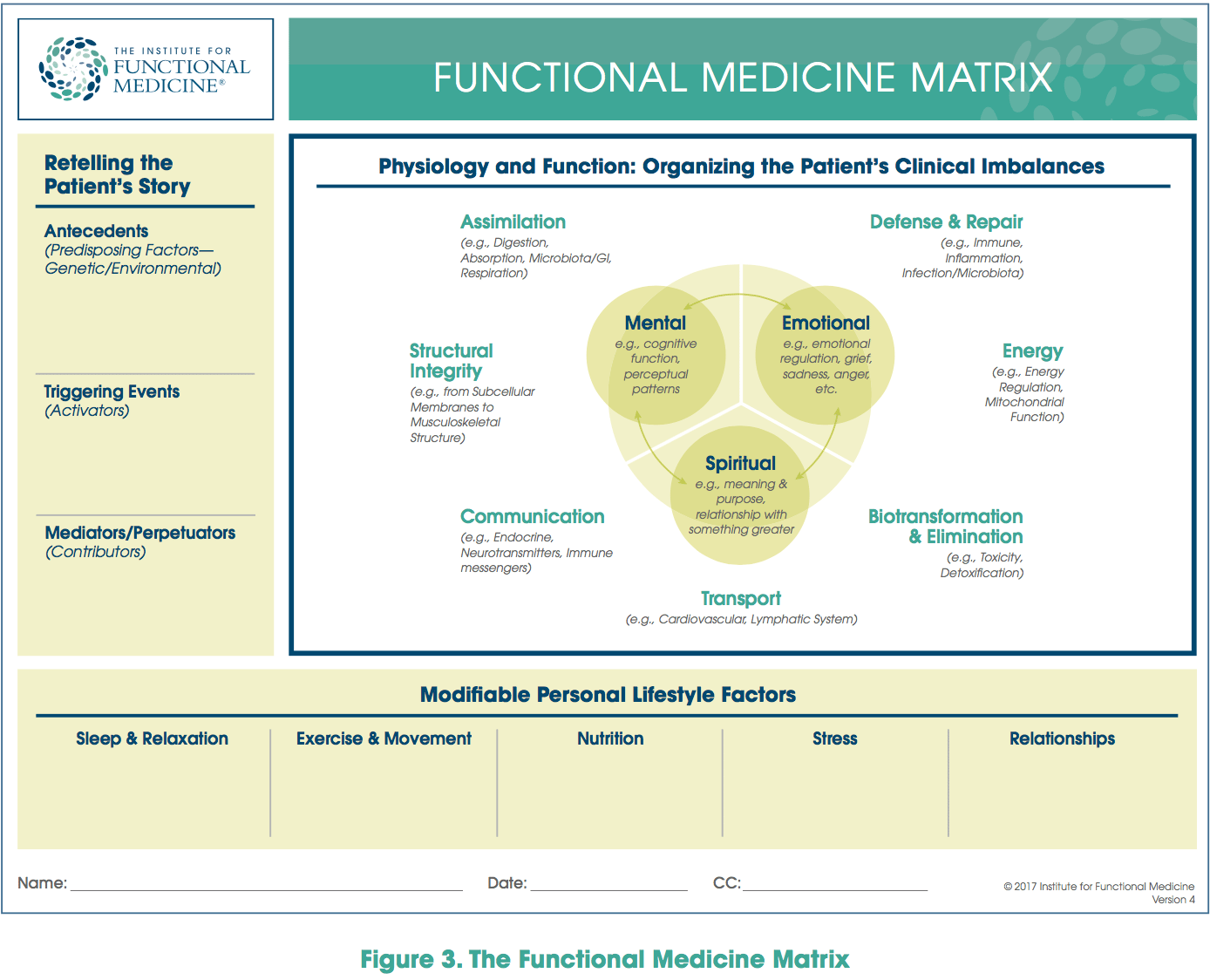

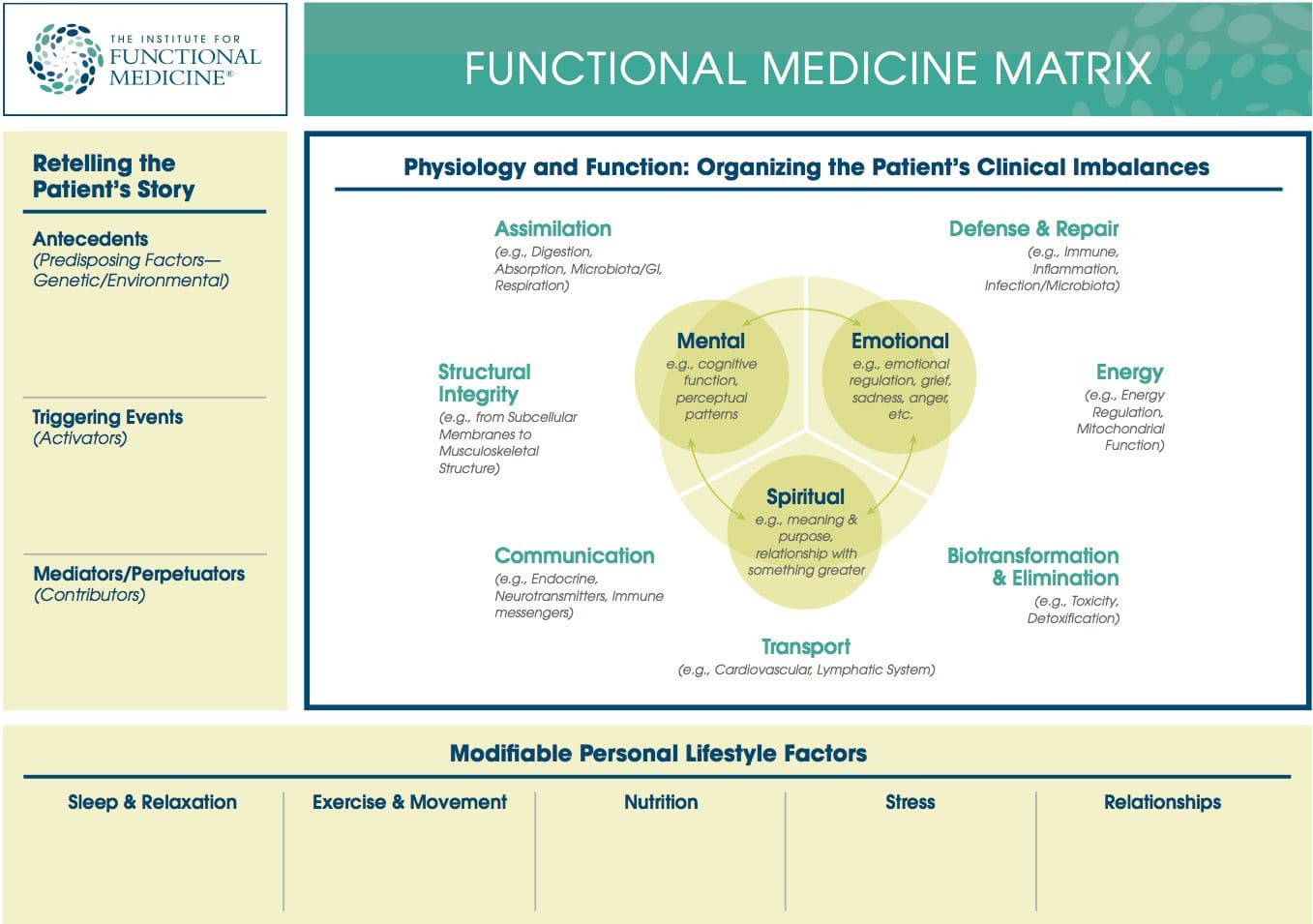

Dysbiosis: A condition that occurs when the normal symbiosis between gut flora and the host is disturbed and organisms of low intrinsic virulence, which normally coexist peacefully with the host, may promote illness. It is distinct from gastrointestinal infection, in which a highly virulent organism gains access to the gastrointestinal tract and infects the host.� Functional Medicine Matrix: The graphic representation of the functional medicine approach, displaying the seven organizing physiological systems, the patient�s known antecedents, triggers, and mediators, and the personalized lifestyle factors that promote health. Practitioners can use the matrix to help organize their thoughts and observations about the patient�s health and decide how to focus therapeutic and preventive strategies.

Functional Medicine Matrix: The graphic representation of the functional medicine approach, displaying the seven organizing physiological systems, the patient�s known antecedents, triggers, and mediators, and the personalized lifestyle factors that promote health. Practitioners can use the matrix to help organize their thoughts and observations about the patient�s health and decide how to focus therapeutic and preventive strategies. Lifestyle Medicine: The use of lifestyle interventions such as nutrition, physical activity, stress reduction, and rest to lower the risk for the approximately 70% of modern health problems that are lifestyle-related chronic diseases (such as obesity and type 2 diabetes), or for the treatment and management of disease if such conditions are already present. It is an essential component of the treatment of most chronic diseases and has been incorporated in many national disease management guidelines.

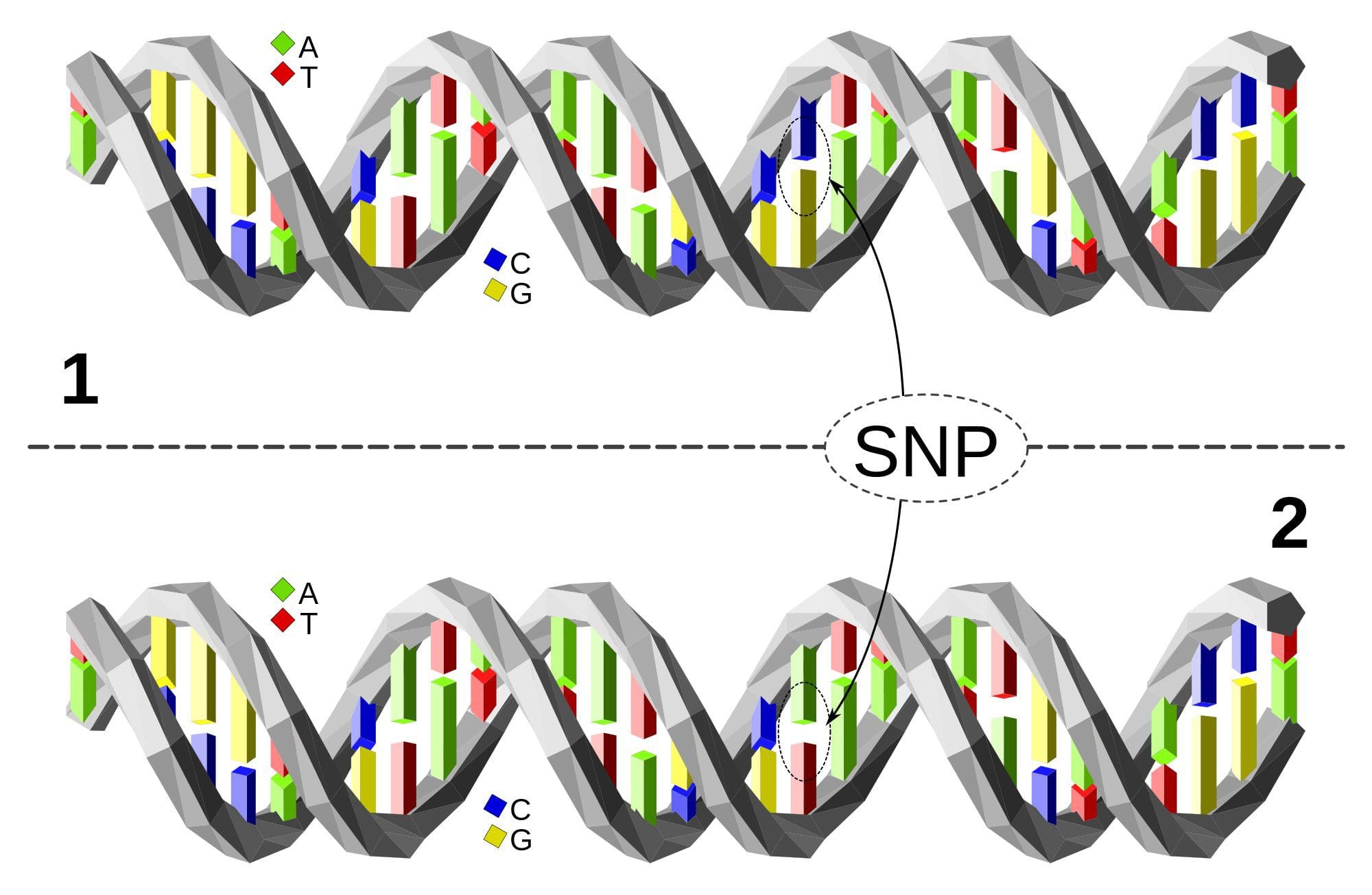

Lifestyle Medicine: The use of lifestyle interventions such as nutrition, physical activity, stress reduction, and rest to lower the risk for the approximately 70% of modern health problems that are lifestyle-related chronic diseases (such as obesity and type 2 diabetes), or for the treatment and management of disease if such conditions are already present. It is an essential component of the treatment of most chronic diseases and has been incorporated in many national disease management guidelines. Single Nucleotide Polymorphism or SNP (pronounced �snip�) is a DNA sequence variation occurring when a single nucleotide�A, T, C, or G�in the genome differs between members of a species or between paired chromosomes in an individual. Almost all common SNPs have only two alleles. These genetic variations underlie differences in our susceptibility to, or protection from, several diseases. Variations in the DNA sequences of humans can affect how humans develop diseases. For example, a single base difference in the genes coding for apolipoprotein E is associated with a higher risk for Alzheimer’s disease. SNPs are also manifestations of genetic variations in the severity of illness, the way our body responds to treatments, and the individual response to pathogens, chemicals, drugs, vaccines, and other agents. They are thought to be key factors in applying the concept of personalized medicine.

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism or SNP (pronounced �snip�) is a DNA sequence variation occurring when a single nucleotide�A, T, C, or G�in the genome differs between members of a species or between paired chromosomes in an individual. Almost all common SNPs have only two alleles. These genetic variations underlie differences in our susceptibility to, or protection from, several diseases. Variations in the DNA sequences of humans can affect how humans develop diseases. For example, a single base difference in the genes coding for apolipoprotein E is associated with a higher risk for Alzheimer’s disease. SNPs are also manifestations of genetic variations in the severity of illness, the way our body responds to treatments, and the individual response to pathogens, chemicals, drugs, vaccines, and other agents. They are thought to be key factors in applying the concept of personalized medicine. Triage Theory: Linus Pauling Award winner Bruce Ames� theory that DNA damage and late onset disease are consequences of a �triage allocation mechanism� developed during evolution to cope with periods of micronutrient shortage. When micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) are scarce, they are consumed for short-term survival at the expense of long-term survival. In 2009, Children�s Hospital and Research Center Oakland concluded that triage theory explains how diseases associated with aging like cancer, heart disease, and dementia (and the pace of aging itself) may be unintended consequences of mechanisms developed during evolution to protect against episodic vitamin/mineral shortages.

Triage Theory: Linus Pauling Award winner Bruce Ames� theory that DNA damage and late onset disease are consequences of a �triage allocation mechanism� developed during evolution to cope with periods of micronutrient shortage. When micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) are scarce, they are consumed for short-term survival at the expense of long-term survival. In 2009, Children�s Hospital and Research Center Oakland concluded that triage theory explains how diseases associated with aging like cancer, heart disease, and dementia (and the pace of aging itself) may be unintended consequences of mechanisms developed during evolution to protect against episodic vitamin/mineral shortages. Xenobiotics: Chemicals found in an organism that are not normally produced by or expected to be present in that organism. This may also include substances present in much higher concentrations than usual. The term xenobiotics is often applied to pollutants such as dioxins and polychlorinated biphenyls, because xenobiotics are understood as substances foreign to an entire biological system, i.e. artificial substances that did not exist in nature before their synthesis by humans. Exposure to several types of xenobiotics has been implicated in cancer risk.

Xenobiotics: Chemicals found in an organism that are not normally produced by or expected to be present in that organism. This may also include substances present in much higher concentrations than usual. The term xenobiotics is often applied to pollutants such as dioxins and polychlorinated biphenyls, because xenobiotics are understood as substances foreign to an entire biological system, i.e. artificial substances that did not exist in nature before their synthesis by humans. Exposure to several types of xenobiotics has been implicated in cancer risk.

The prevalence of obesity in the United States has been increasing for almost 50 years. Currently, more than two-thirds of adults and almost one-third of children and adolescents are

The prevalence of obesity in the United States has been increasing for almost 50 years. Currently, more than two-thirds of adults and almost one-third of children and adolescents are

From 2005 to 2014, there was a 1.4% annual increase in cancers related to overweight and obesity among individuals aged 20 to 49 years and a 0.4% increase in these cancers among individuals aged 50 to 64 years. For example, if cancer rates had stayed the same in 2014 as they were in 2005, there would have been 43?000 fewer cases of colorectal cancer but 33?000 more cases of other cancers related to overweight and obesity. Nearly half of all cancers in people younger than 65 years were associated with overweight and obesity. Overweight and obesity among younger people may exact a toll on individuals� health earlier in their lifetimes.

From 2005 to 2014, there was a 1.4% annual increase in cancers related to overweight and obesity among individuals aged 20 to 49 years and a 0.4% increase in these cancers among individuals aged 50 to 64 years. For example, if cancer rates had stayed the same in 2014 as they were in 2005, there would have been 43?000 fewer cases of colorectal cancer but 33?000 more cases of other cancers related to overweight and obesity. Nearly half of all cancers in people younger than 65 years were associated with overweight and obesity. Overweight and obesity among younger people may exact a toll on individuals� health earlier in their lifetimes.

The

The  Implementation of clinical interventions, including screening, counseling, and referral, has major challenges. Since 2011, Medicare has covered behavioral counseling sessions for weight loss in primary care settings. However, the benefit has not been widely utilized.

Implementation of clinical interventions, including screening, counseling, and referral, has major challenges. Since 2011, Medicare has covered behavioral counseling sessions for weight loss in primary care settings. However, the benefit has not been widely utilized. Achieving sustainable weight loss requires comprehensive strategies that support patients� efforts to make significant lifestyle changes. The availability of clinical and community programs and services to which to refer patients is critically important. Although such programs are available in some communities, there are gaps in availability. Furthermore, even when these programs are available, enhancing linkages between clinical and community care could improve patients� access. Linking community obesity prevention, weight management, and physical activity programs with clinical services can connect people to valuable prevention and intervention resources in the communities where they live, work, and play. Such linkages can give individuals the encouragement they need for the lifestyle changes that maintain or improve their health.

Achieving sustainable weight loss requires comprehensive strategies that support patients� efforts to make significant lifestyle changes. The availability of clinical and community programs and services to which to refer patients is critically important. Although such programs are available in some communities, there are gaps in availability. Furthermore, even when these programs are available, enhancing linkages between clinical and community care could improve patients� access. Linking community obesity prevention, weight management, and physical activity programs with clinical services can connect people to valuable prevention and intervention resources in the communities where they live, work, and play. Such linkages can give individuals the encouragement they need for the lifestyle changes that maintain or improve their health. The high prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States will continue to contribute to increases in health consequences related to obesity, including cancer. Nonetheless, cancer is not inevitable; it is possible that many cancers related to overweight and obesity could be prevented, and physicians have an important responsibility in educating patients and supporting patients� efforts to lead healthy lifestyles. It is important for all health care professionals to emphasize that along with quitting or avoiding tobacco, achieving and maintaining a healthy weight are also important for reducing the risk of cancer.