Chiropractic & Stress Management for Back Pain in El Paso, TX

Stress is a reality of contemporary living. In a society where work hours are increasing and the media is constantly overloading our senses with the most regent tragedy, it’s no wonder why so many people experience higher levels of stress on a regular basis. Fortunately, more healthcare professionals are implementing stress management methods and techniques as a part of a patient’s treatment. While stress is a natural response which helps prepare the body for danger, constant stress can have negative effects on the body, causing symptoms of back pain and sciatica. But, why does too much stress negatively affect the human body?

First, it’s important to understand how the body perceives stress. There are three basic “channels” through which we perceive stress: environment, body, and emotions. Environmental stress is rather self-explanatory; if you’re walking down a quiet road and you hear a loud bang nearby, your body will perceive that as an immediate danger. That is an environmental stressor. Pollution could be another example of environmental stress because it externally affects the body the more one is exposed to it.

Stress through the body includes disease, lack of sleep and/or improper nutrition. Emotional stress is a little different, since it involves the way our brains interpret certain things. For instance, if someone you work with is being passive-aggressive, you might become stressed. Thoughts such as, “is he mad at me for some reason” or “they must be having a tough morning”, could be perceived as emotional stress. What is unique about emotional stress, however, is that we have control on just how much of it we experience, much more so than environmental or body stressors.

Now that we understand how the body can perceive stress in a variety of ways, we can discuss what effects constant stress can have on our overall health and wellness. When the body is placed under stress, through any of the above mentioned channels, the body’s fight or flight response is triggered. The sympathetic nervous system, or SNS, becomes stimulated, which in turn makes the heart beats faster and all of the body’s senses become more intense. This is a leftover defense mechanism from prehistoric times; that is the reason we’ve survived to today, instead of all becoming lunch for hungry predators out in the wild.

Unfortunately, the real issue is that in contemporary society, people often become overstressed and the human body is unable to differentiate between an immediate threat and a simple societal issue. Over the years many research studies have been conducted to estimate the effect of chronic stress on the human body, with such effects as hypertension, increased risk for heart disease and damage to muscle tissue as well as symptoms of back pain and sciatica.

According to several other research studies, combining stress management methods and techniques with a variety of treatment options can help more effectively improve symptoms and can promote a faster recovery. Chiropractic care is a well-known alternative treatment option utilized to treat a variety of injuries and/or conditions of the musculoskeletal and nervous systems. Because chiropractic treatment focuses on the spine, the root of the nervous system, chiropractic can also help with stress. Among the effects of stress is strain, which may consequently lead to subluxation or misalignment of the spine. Spinal adjustment and manual manipulations can help ease muscle tension, which in turn eases the strain on specific areas of the spine and helps ease subluxation. A balanced spine is a crucial element of handling personal stress. As mentioned before, proper nutrition and sufficient sleep is also a crucial part of stress management, which is chiropractic care offers lifestyle modification advice to further improve the patient’s stress levels as well as decrease their symptoms.

The purpose of the article below is to demonstrate the research study process developed to compare complementary and alternative medicine with conventional mind-body therapies for chronic back pain. The randomized controlled trial was carefully conducted and the details behind the research study have been recorded below. As with other research studies, further evidence-based information may be required to effectively determine the effect of stress management with treatment for back pain.

Comparison of Complementary and Alternative Medicine with Conventional Mind�Body Therapies for Chronic Back Pain: Protocol for the Mind�Body Approaches to Pain (MAP) Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

Background

The self-reported health and functional status of persons with back pain in the United States have declined in recent years, despite greatly increased medical expenditures due to this problem. Although patient psychosocial factors such as pain-related beliefs, thoughts and coping behaviors have been demonstrated to affect how well patients respond to treatments for back pain, few patients receive treatments that address these factors. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), which addresses psychosocial factors, has been found to be effective for back pain, but access to qualified therapists is limited. Another treatment option with potential for addressing psychosocial issues, mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), is increasingly available. MBSR has been found to be helpful for various mental and physical conditions, but it has not been well-studied for application with chronic back pain patients. In this trial, we will seek to determine whether MBSR is an effective and cost-effective treatment option for persons with chronic back pain, compare its effectiveness and cost-effectiveness compared with CBT and explore the psychosocial variables that may mediate the effects of MBSR and CBT on patient outcomes.

Methods/Design

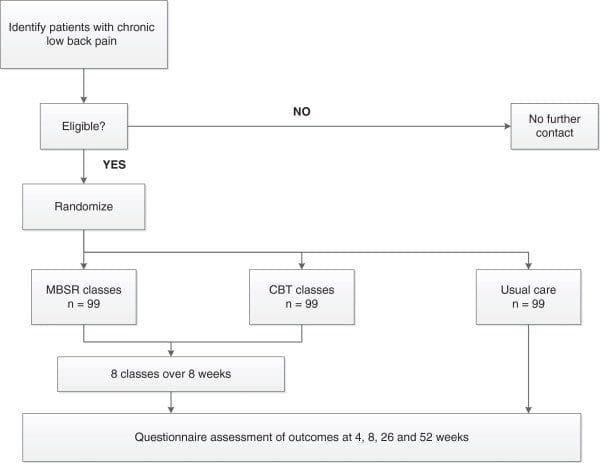

In this trial, we will randomize 397 adults with nonspecific chronic back pain to CBT, MBSR or usual care arms (99 per group). Both interventions will consist of eight weekly 2-hour group sessions supplemented by home practice. The MBSR protocol also includes an optional 6-hour retreat. Interviewers masked to treatment assignments will assess outcomes 5, 10, 26 and 52 weeks postrandomization. The primary outcomes will be pain-related functional limitations (based on the Roland Disability Questionnaire) and symptom bothersomeness (rated on a 0 to 10 numerical rating scale) at 26 weeks.

Discussion

If MBSR is found to be an effective and cost-effective treatment option for patients with chronic back pain, it will become a valuable addition to the limited treatment options available to patients with significant psychosocial contributors to their pain.

Trial Registration

Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT01467843.

Keywords: Back pain, Cognitive-behavioral therapy, Mindfulness meditation

Background

Identifying cost-effective treatments for chronic low back pain (CLBP) remains a challenge for clinicians, researchers, payers and patients. About $26 billion is spent annually in the United States in direct costs of medical care for back pain [1]. In 2002, the estimated costs of lost worker productivity due to back pain were $19.8 billion [2]. Despite numerous options for evaluating and treating back pain, as well as the greatly increased medical care resources devoted to this problem, the health and functional status of persons with back pain in the United States has deteriorated [3]. Furthermore, both providers and patients are dissatisfied with the status quo [4-6] and continue to search for better treatment options.

There is substantial evidence that patient psychosocial factors, such as pain-related beliefs, thoughts and coping behaviors, can have a significant impact on the experience of pain and its effects on functioning [7]. This evidence highlights the potential value of treatments for back pain that address both the mind and the body. In fact, four of the eight nonpharmacologic treatments recommended by the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society guidelines for persistent back pain include �mind�body� components [8]. One of these treatments, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), includes mind�body components such as relaxation training and has been found to be effective for a variety of chronic pain problems, including back pain [9-13]. CBT has become the most widely applied psychosocial treatment for patients with chronic back pain. Another mind�body therapy, mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) [14,15], focuses on teaching techniques to increase mindfulness. MBSR and related mindfulness-based interventions have been found to be helpful for a broad range of mental and physical health conditions, including chronic pain [14-19], but they have not been well-studied for chronic back pain [20-24]. Only a few small pilot trials have evaluated the effectiveness of MBSR for back pain [25,26] and all reported improvements in pain intensity [27] or patients� acceptance of pain [28,29].

Further research on the comparative effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of mind�body therapies should be a priority in back pain research for the following reasons: (1) the large personal and societal impact of chronic back pain, (2) the modest effectiveness of current treatments, (3) the positive results of the few trials in which researchers have evaluated mind�body therapies for back pain and (4) the growing popularity and safety, as well as the relatively low cost, of mind�body therapies. To help fill this knowledge gap, we are conducting a randomized trial to evaluate the effectiveness, comparative effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of MBSR and group CBT, compared with usual medical care only, for patients with chronic back pain.

Specific Aims

Our specific aims and their corresponding hypotheses are outlined below.

- 1. To determine whether MBSR is an effective adjunct to usual medical care for persons with CLBP

- Hypothesis 1: Individuals randomized to the MBSR course will show greater short-term (8 and 26 weeks) and long-term (52 weeks) improvement in pain-related activity limitations, pain bothersomeness and other health-related outcomes than those randomized to continued usual care alone.

- 2. To compare the effectiveness of MBSR and group CBT in decreasing back pain�related activity limitations and pain bothersomeness

- Hypothesis 2: MBSR will be more effective than group CBT in decreasing pain-related activity limitations and pain bothersomeness in both the short term and long term. The rationale for this hypothesis is based on (1) the modest effectiveness of CBT for chronic back pain found in past studies, (2) the positive results of the limited initial research evaluating MBSR for chronic back pain and (3) growing evidence that an integral part of MBSR training (but not CBT training)�yoga�is effective for chronic back pain.

- 3. To identify the mediators of any observed effects of MBSR and group CBT on pain-related activity limitations and pain bothersomeness

- Hypothesis 3a: The effects of MBSR on activity limitations and pain bothersomeness will be mediated by increases in mindfulness and acceptance of pain.

- Hypothesis 3b: The effects of CBT on activity limitations and pain bothersomeness will be mediated by changes in pain-related cognition (decreases in catastrophizing, beliefs that one is disabled by pain and beliefs that pain signals harm, as well as increases in perceived control over pain and self-efficacy for managing pain) and changes in coping behaviors (increased use of relaxation, task persistence and coping self-statements and decreased use of rest).

- 4. To compare the cost-effectiveness of MBSR and group CBT as adjuncts to usual care for persons with chronic back pain

- Hypothesis 4: Both MBSR and group CBT will be cost-effective adjuncts to usual care.

We will also explore whether certain patient characteristics predict or moderate treatment effects. For example, we will explore whether patients with higher levels of depression are less likely to improve with both CBT and MBSR or whether such patients are more likely to benefit from CBT than from MBSR (that is, whether depression level is a moderator of treatment effects).

Methods/Design

Overview

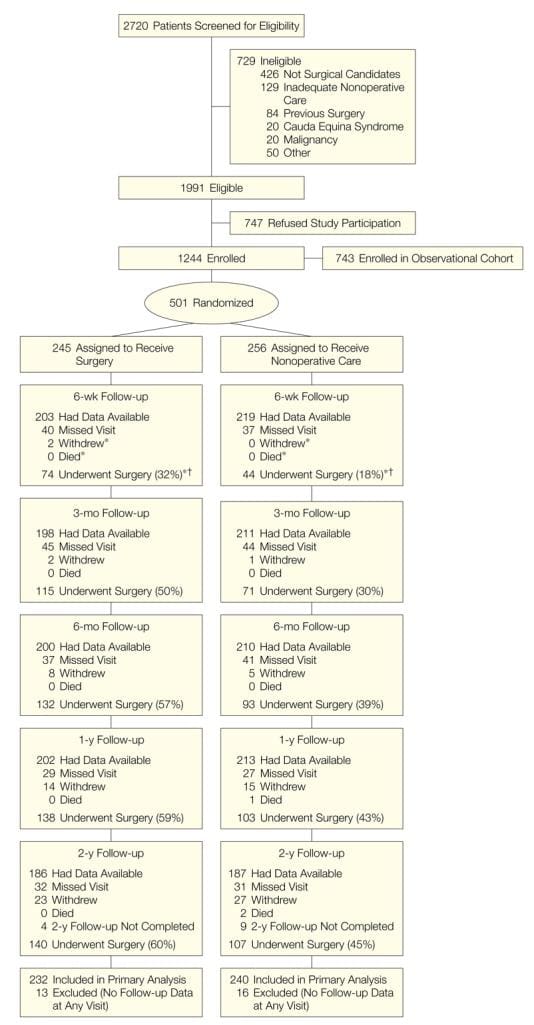

We are conducting a randomized clinical trial in which individuals with CLBP are randomly assigned to group CBT, a group MBSR course or usual care alone (Figure 1). Participants will be followed for 52 weeks after randomization. Telephone interviewers masked to participants� treatment assignments will assess outcomes 4, 8, 26 and 52 weeks postrandomization. The primary outcomes we will assess are pain-related activity limitations and pain bothersomeness. Participants will be informed that the study researchers are comparing �two different widely used pain self-management programs that have been found helpful for reducing pain and making it easier to carry out daily activities�.

Figure 1: Flowchart of the trial protocol. CBT, Cognitive-behavioral therapy; MBSR, Mindfulness-based stress reduction.

The protocol for this trial has been approved by the Human Subjects Review Committee of the Group Health Cooperative (250681-22). All participants will be required to give their informed consent before enrollment in this study.

Study Sample and Setting

The primary source of participants for this trial will be the Group Health Cooperative (GHC), a group-model, not-for-profit health-care organization that serves over 600,000 enrollees through its own primary care facilities in Washington state. As needed to achieve recruitment goals, direct mailings will be sent to persons 20 to 70 years of age living in the areas served by the GHC.

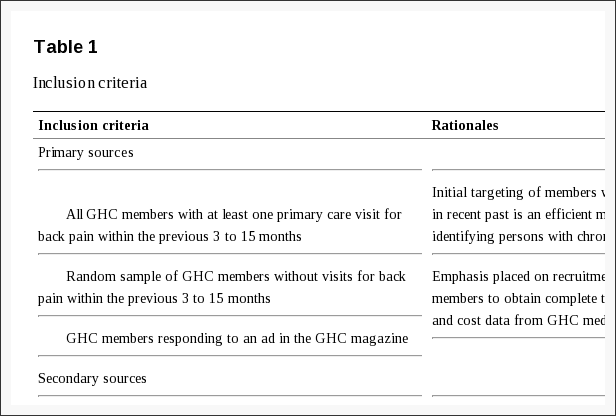

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

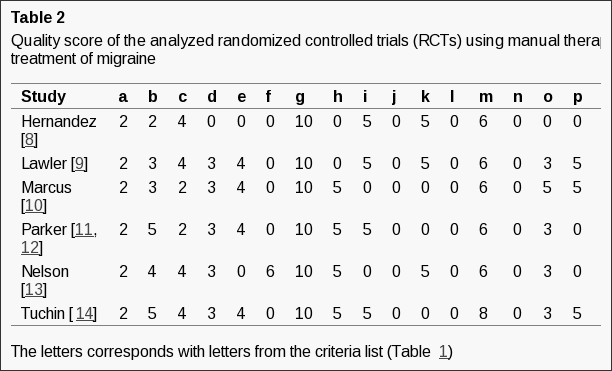

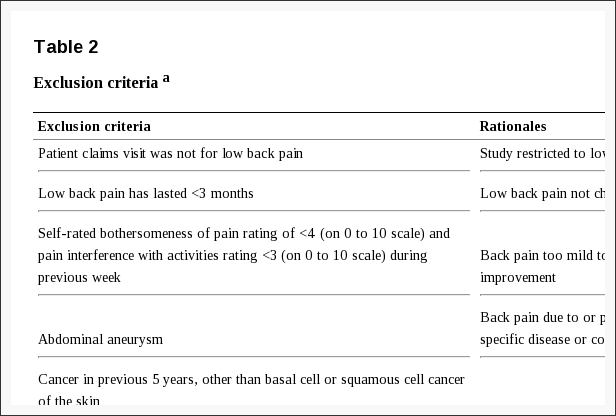

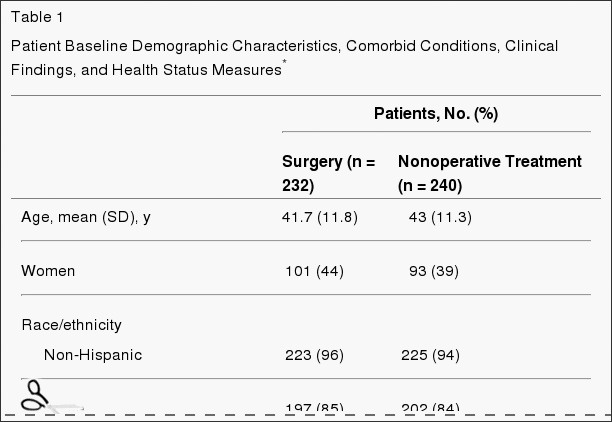

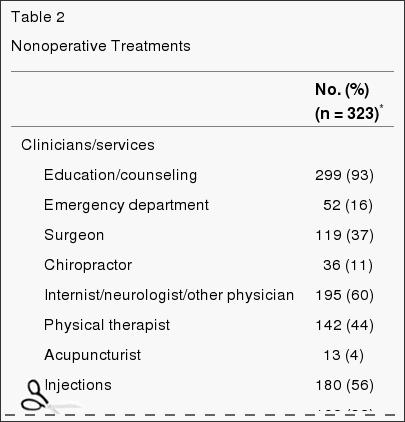

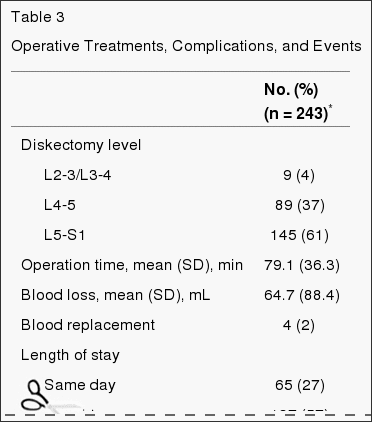

We are recruiting individuals from 20 to 70 years of age whose back pain has persisted for at least 3 months. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed to maximize the enrollment of appropriate patients while screening out patients who have low back pain of a specific nature (for example, spinal stenosis) or a complicated nature or who would have difficulty completing the study measures or interventions (for example, psychosis). Reasons for exclusion of GHC members were identified on the basis of (1) automated data recorded (using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision coding system), during all visits over the course of the previous year and (2) eligibility interviews conducted by telephone. For non-GHC members, reasons for exclusion were identified on the basis of telephone interviews. Tables 1 and ?2 list the inclusion and exclusion criteria, respectively, as well as the rationale for each criterion and the information sources.

In addition, we require that participants be willing and able to attend the CBT or MBSR classes during the 8-week intervention period if assigned to one of those treatments, and to respond to the four follow-up questionnaires so that we can assess outcomes.

Recruitment Procedures

Because the study intervention involves classes, we are recruiting participants in ten cohorts consisting of up to forty-five individuals each. We are recruiting participants from three main sources: (1) GHC members who have made visits to their primary care providers for low back pain and whose pain has persisted for at least 3 months, (2) GHC members who have not made a visit to their primary care provider for back pain but who are between the ages of 20 and 70 years and who respond to our nontargeted GHC mailing or our ad in GHC�s twice-yearly magazine and (3) community residents between the ages of 20 and 70 years who respond to a direct mail recruitment postcard.

For the targeted GHC population, a programmer will use GHC�s administrative and clinical electronic databases to identify potentially eligible members with a visit in the previous 3 to 15 months to a provider that resulted in a diagnosis consistent with nonspecific low back pain. These GHC members are mailed a letter and consent checklist that explains the study and eligibility requirements. Members interested in participating sign and return a statement indicating their willingness to be contacted. A research specialist then calls the potential participant to ask questions; determine eligibility; clarify risks, benefits and expected commitment to the study; and request informed consent. After informed consent has been obtained from the individual, the baseline telephone assessment is conducted.

For the nontargeted GHC population (that is, GHC members without visits with back pain diagnoses received within the previous 3 to 15 months but who could possibly have low back pain), a programmer uses administrative and clinical electronic databases to identify potentially eligible members who were not included in the targeted sample described in the preceding paragraph. This population also includes GHC members who respond to an ad in the GHC magazine. The same methods used for the targeted population are then used to contact and screen the potential participants, obtain their informed consent and collect baseline data.

With regard to community residents, we have purchased lists of the names and addresses of a randomly selected sample of people living within our recruitment area who are between 20 and 70 years of age. The people on the list are sent direct mail postcards describing the study including information regarding how to contact study staff if interested in participating. Once an interested person has contacted the research team the same process detailed above is followed.

To ensure that all initially screened study participants remain eligible at the time the classes begin, those who consent more than 14 days prior to the start of the intervention classes will be recontacted approximately 0 to 14 days prior to the first class to reconfirm their eligibility. The primary concern is to exclude persons who no longer have at least moderate baseline ratings of pain bothersomeness and pain-related interference with activities. Those individuals who remain eligible and give their final informed consent will be administered the baseline questionnaire.

Randomization

After completing the baseline assessment, participants will be randomized in equal proportions to the MBSR, CBT or usual care group. Those randomized to the MBSR or CBT group will not be informed of their type of treatment until they arrive at the first classes, which will occur simultaneously in the same building. The intervention group will be assigned on the basis of a computer-generated sequence of random numbers using a program which ensures that allocation cannot be changed after randomization. To ensure balance on a key baseline prognostic factor, randomization will be stratified based on our primary outcome measurement instrument: the modified version of the Roland Disability Questionnaire (RDQ) [30,31]. We will stratify participants into two activity limitations groups: moderate (RDQ score ?12 on a 0 to 23 scale) and high (RDQ scores ?13). Participants will be randomized within these strata in blocks of varying size (three, six or nine) to ensure a balanced but unpredictable assignment of participants. During recruitment, the study biostatistician will receive aggregated counts of participants randomized to each group to assure that the preprogrammed randomization algorithm is functioning properly.

Study Treatments

Both the group CBT and MBSR class series consist of eight weekly 2-hour sessions supplemented by home activities.

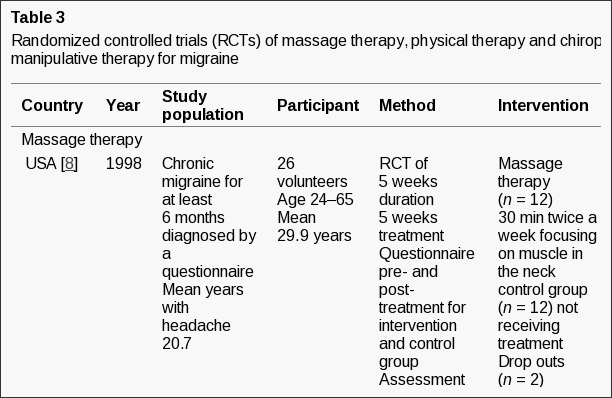

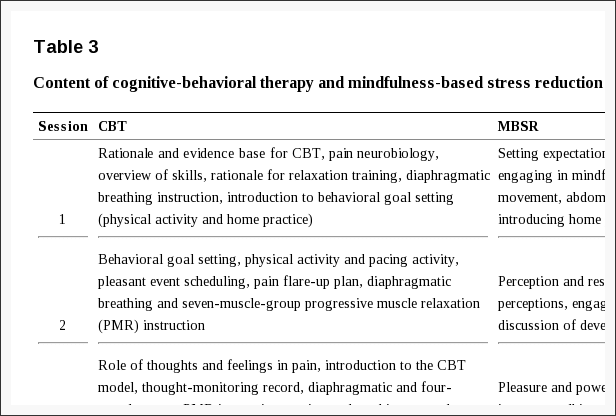

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction

Mindfulness-based stress reduction, a 30-year-old treatment program developed by Jon Kabat-Zinn, is well-described in the literature [32-34]. The authors of a recent meta-analysis found that MBSR had moderate effect sizes for improving the physical and mental well-being of patients with a variety of health conditions [16]. Our MBSR program is closely modeled on the original one and includes eight weekly 2-hour classes (summarized in Table 3), a 6-hour retreat between weeks 6 and 7 and up to 45 minutes per day of home practice. Our MBSR protocol was adapted by a senior MBSR instructor from the 2009 MBSR instructor�s manual used at the University of Massachusetts [35]. This manual permits latitude in how instructors introduce mindfulness and its practice to participants. The handouts and home practice materials are standardized for this study.

Table 3: Content of cognitive-behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction class sessions.

Participants will be given a packet of information during the first class that includes a course outline and instructor contact information; information about mindfulness, meditation, communication skills and effects of stress on the body, emotions and behavior; homework assignments; poems; and a bibliography. All sessions will include mindfulness exercises, and all but the first will include yoga or other forms of mindful movement. Participants will be given audio recordings of the mindfulness and yoga techniques, which will have been recorded by their own instructors. Participants will be asked to practice the techniques discussed in each class daily for up to 45 minutes throughout the intervention period and after classes end. They will also be assigned readings to complete before each class. Time will be devoted in each class to a review of challenges that participants have had in practicing what they learned in previous classes and with their homework. An optional day of practice on the Saturday between the sixth and seventh classes will be offered. This 6-hour �retreat� will be held with the participants in silence and only the instructor speaking. This will provide participants an opportunity to deepen what they have learned in class.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

CBT for chronic pain is well-described in the literature and has been found to be modestly to moderately effective in improving chronic pain problems [9-13]. There is no single, standardized CBT intervention for chronic pain, although all CBT interventions are based on the assumption that both cognition and behavior influence adaptation to chronic pain and that maladaptive cognition and behavior can be identified and changed to improve patient functioning [36]. CBT emphasizes active, structured techniques to teach patients how to identify, monitor and change maladaptive thoughts, feelings and behaviors, with a focus on helping patients to acquire skills that they can apply to a variety of problems and collaboration between the patient and therapist. A variety of techniques are taught, including training in pain coping skills (for example, use of positive coping self-statements, distraction, relaxation and problem-solving). CBT also promotes setting and working toward behavioral goals.

Both individual and group formats have been used in CBT. Group CBT is often an important component of multidisciplinary pain treatment programs. We will use a group CBT format because it has been found to be efficacious [37-40], is more resource-efficient than individual therapy and provides patients with the potential benefits deriving from contact with, and support and encouragement from, others with similar experiences and problems. In addition, using group formats for both MBSR and CBT will eliminate intervention format as a possible explanation for any differences observed between the two therapies.

For this study, we developed a detailed therapist�s manual with content specific for each session, as well as a participant�s workbook containing materials for use in each session. We developed the therapist�s manual and participant�s workbooks based on existing published resources as well as on materials we have used in prior studies [39-47].

The CBT intervention (Table 3) will consist of eight weekly 2-hour sessions that will provide (1) education about the role of maladaptive automatic thoughts (for example, catastrophizing) and beliefs (for example, one�s ability to control pain, hurt equals harm) common in people with depression, anxiety and/or chronic pain and (2) instruction and practice in identifying and challenging negative thoughts, the use of thought-stopping techniques, the use of positive coping self-statements and goal-setting, relaxation techniques and coping with pain flare-ups. The intervention will also include education about activity pacing and scheduling and about relapse prevention and maintenance of gains. Participants will be given audio recordings of relaxation and imagery exercises and asked to set goals regarding their relaxation practice. During each session, participants will complete a personal action plan for activities to be completed between sessions. These plans will be used as logs for setting specific home practice goals and checking off activities completed during the week to be reviewed at the next week�s session.

Usual Care

The usual care group will receive whatever medical care they would normally receive during the study period. To minimize possible disappointment with not being randomized to a mind�body treatment, participants in this group will receive $50 compensation.

Class Sites

The CBT and MBSR classes will be held in facilities close to concentrations of GHC members in Washington state (Bellevue, Bellingham, Olympia, Seattle, Spokane and Tacoma).

Instructors

All MBSR instructors will have received either formal training in teaching MBSR from the Center for Mindfulness at the University of Massachusetts or equivalent training. They will themselves be practitioners of both mindfulness and a body-oriented discipline (for example, yoga), will have taught MBSR previously and will have made mindfulness a core component of their lives. The CBT intervention will be conducted by doctorate-level clinical psychologists with previous experience in providing CBT to patients with chronic pain.

Training and Monitoring of Instructors

All CBT instructors will be trained in the study protocol for the CBT intervention by the study�s clinical psychologist investigators (BHB and JAT), who are very experienced in administering CBT to patients with chronic pain. BHB will supervise the CBT instructors. One of the investigators (KJS) will train the MBSR instructors in the adapted MBSR protocol and supervise them. Each instructor will attend weekly supervision sessions, which will include discussion of positive experiences, adverse events, concerns raised by the instructor or participants and protocol fidelity. Treatment fidelity checklists highlighting the essential components for each session were created for both the CBT and MBSR arms. A trained research specialist will use the fidelity checklist during live observation of every session. The research specialist will provide feedback to the supervisor to facilitate weekly supervision of the instructors. In addition, all sessions will be audio-recorded. The supervisors will listen to a random sample and requested portions of sessions and will monitor them using the fidelity checklist. Feedback will be provided to the instructors during their weekly supervision sessions. Treatment fidelity will be monitored in both intervention groups by KJS and BHB with assistance from research specialists. In addition, they will review and rate on the fidelity checklist a random sample of the recorded sessions.

Participant Retention and Adherence to Home Practice

Participants will receive a reminder call before the first class and whenever they miss a class. They will be asked to record their daily home practice on weekly logs. Questions about their home practice during the prior week will also be included in all follow-up interviews. To maintain interviewer blinding, adherence questions will be asked after all outcome data have been recorded.

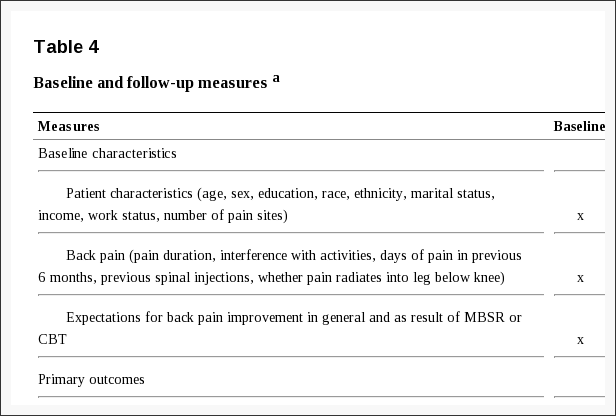

Measures

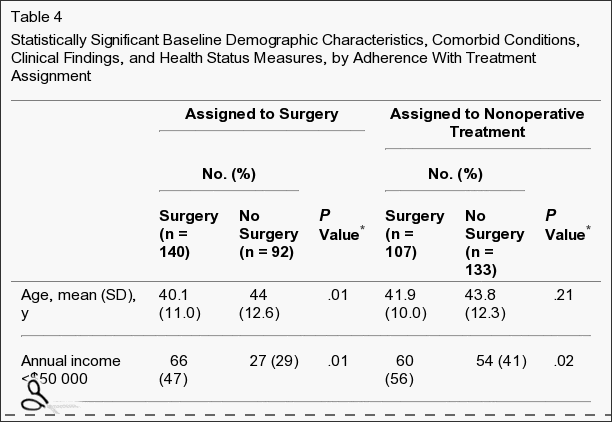

We will assess a variety of participant baseline characteristics, including sociodemographic characteristics, back pain history and expectations of the helpfulness of the mind�body treatments for back pain (Table 4).

We will assess a core set of outcomes for patients with spinal disorders (back-related function, pain, general health status, work disability and patient satisfaction) [48] that are consistent with the Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials recommendations for clinical trials of chronic pain treatment efficacy and effectiveness [49]. We will measure both short-term outcomes (8 and 26 weeks) and long-term outcomes (52 weeks). We will also include a brief, 4-week, midtreatment assessment to permit analyses of the hypothesized mediators of the effects of MBSR and CBT on the primary outcomes. The primary study endpoint is 26 weeks. Participants will be paid $20 for each follow-up interview completed to maximize response rates.

Co�Primary Outcome Measures

The co�primary outcome measures will be back-related activity limitations and back pain bothersomeness.

Back-related activity limitations will be measured with the modified RDQ, which asks whether 23 specific activities have been limited due to back pain (yes or no) [30]. We have further modified the RDQ to ask a question about the previous week rather than just �today�. The original RDQ has been found to be reliable, valid and sensitive to clinical changes [31,48,50-53], and it is appropriate for telephone administration and use with patients with moderate activity limitations [50].

Back pain bothersomeness will be measured by asking participants to rate how bothersome their back pain has been during the previous week on a 0 to 10 scale (0?=?�not at all bothersome� and 10?=?�extremely bothersome�). On the basis of data compiled from a similar group of GHC members with back pain, we found this bothersomeness measure to be highly correlated with a 0 to 10 measure of pain intensity (r?=?0.8 to 0.9; unpublished data (DCC and KJS) and with measures of function and other outcome measures [54]. The validity of numerical rating scales of pain has been well-documented, and such scales have demonstrated sensitivity in detecting changes in pain after treatment [55].

We will analyze and report these co�primary outcomes in two ways. First, for our primary endpoint analyses, we will compare the percentages of participants in the three treatment groups who achieve clinically meaningful improvement (?30% improvement from baseline) [56,57] at each time point (with 26-week follow-up being the primary endpoint). We will then examine, in a secondary outcome analysis, the adjusted mean differences between groups on these measures at the time of follow-up.

Secondary Outcome Measures

The secondary outcomes that we will measure are depressive symptoms, anxiety, pain-related activity interference, global improvement with treatment, use of medications for back pain, general health status and qualitative outcomes.

Depressive symptoms will be assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8) [58]. With the exception of the elimination of a question about suicidal ideation, the PHQ-8 is identical to the PHQ-9, which has been found to be reliable, valid and responsive to change [59,60].

Anxiety will be measured with the 2-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-2), which has demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity in detecting generalized anxiety disorder in primary care populations [61,62].

Pain-related activity interference with daily activities will be assessed using three items from the Graded Chronic Pain Scale (GCPS). The GCPS has been validated and shown to have good psychometric properties in a large population survey and in large samples of primary care patients with pain [63,64]. Participants will be asked to rate the following three items on a 0 to 10 scale: their current back pain (back pain �right now�), their worst back pain in the previous month and their average pain level over the previous month.

Global improvement with treatment will be measured with the Patient Global Impression of Change scale [65]. This single question asks participants to rate their improvement with treatment on a 7-point scale that ranges from �very much improved� to �very much worse,� with �no change� used as the midpoint. Global ratings of improvement with treatment provide a measure of overall clinical benefit from treatment and are considered one of the core outcome domains in pain clinical trials [49].

Use of medications and exercise for back pain during the previous week will be assessed with the 8-, 26- and 52-week questionnaires.

General health status will be assessed with the 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) [66], a widely used instrument that yields summary scores for physical and mental health status. The SF-12 will also be used to calculate quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) using the Short Form Health Survey in 6 dimensions in the cost-effectiveness analyses [67].

Qualitative outcomes will be measured with open-ended questions. We have included open-ended questions in our previous trials and found that they yield valuable insights into participants� feelings about the value of specific components of the interventions and the impact of the interventions on their lives. We therefore will include open-ended questions about these issues at the end of the 8-, 26- and 52-week follow-up interviews.

Measures Used in Mediator Analyses

In the MBSR arm, we will evaluate the mediating effects of increased mindfulness (measured with the Nonreactivity, Observing, Acting with Awareness, and Nonjudging subscales of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire short form [68-70]) and increased pain acceptance (measured with the Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire [71,72]) on the primary outcomes. In the CBT arm, we will evaluate the mediating effects of improvements in pain beliefs and/or appraisals (measured with the Patient Self-Efficacy Questionnaire [73]; the Survey of Pain Attitudes 2-item Control, Disability, and Harm scales [74-76]; and the Pain Catastrophizing Scale [77-80]) and changes in the use of pain coping strategies (measured with the Chronic Pain Coping Inventory 2-item Relaxation scale and the complete Activity Pacing scale [81,82]) on the primary outcomes. Although we expect the effects of MBSR and CBT on outcomes to be mediated by different variables, we will explore the effects of all potential mediators on outcomes in both treatment groups.

Measures Used in the Cost-Effectiveness Analyses

Direct costs will be estimated using cost data extracted from the electronic medical records for back-related services provided or paid by GHC and from patient reports of care not covered by GHC. Indirect costs will be estimated using the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire [83]. The effectiveness of the intervention will be derived from the SF-12 general health status measure [84].

Data Collection, Quality Control and Confidentiality

Data will be collected from participants by trained telephone interviewers using a computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI) version of the questionnaires to minimize errors and missing data. Questions about experiences with specific aspects of the interventions (for example, yoga, meditation, instruction in coping strategies) that would unmask interviewers to treatment groups will be asked at each time point after all other outcomes have been assessed. We will attempt to obtain outcome data from all participants in the trial, including those who never attend or drop out of the classes, those who discontinue enrollment in the health plan and those who move away. Participants who do not respond to repeated attempts to obtain follow-up data by telephone will be mailed a questionnaire including only the two primary outcome measures and offered $10 for responding.

We are will collect information at every stage of recruitment, randomization and treatment so that we can report patient flow according to the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) guidelines [85]. To maintain the confidentiality of patient-related information in the database, unique participant study numbers will be used to identify patient outcomes and treatment data. Study procedures are in place to ensure that all masked personnel will remain masked to treatment group.

Protection of Human Participants and Assessment of Safety

Protection of Human Participants

The GHC Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved this study.

Safety Monitoring

This trial will be monitored for safety by an independent Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) composed of a primary care physician experienced in mindfulness, a biostatistician and a clinical psychologist with experience in treating patients with chronic pain.

Adverse Experiences

We will collect data on adverse experiences (AEs) from several sources: (1) reports from the CBT and MBSR instructors of any participants� experiences of concern to them; (2) the 8-, 26- and 52-week CATI follow-up interviews in which the participants are asked about any harm they felt during the CBT or MBSR treatment and any serious health problems they had had during the respective time periods; and (3) spontaneous reports from participants. The project coinvestigators and a GHC primary care internist will review AE reports from all sources weekly. Any serious AEs will be reported promptly to the GHC IRB and the DSMB. AEs that are not serious will be recorded and included in regular DSMB reports. Any identified deaths of participants will be reported to the DSMB chair within 7 days of discovery, regardless of attribution.

Stopping Rules

The trial will be stopped only if the DSMB believes that there is an unacceptable risk of serious AEs in one or more of the treatment arms. In this case, the DSMB can decide to terminate one of the arms of the trial or the entire trial.

Statistical Issues

Sample Size and Detectable Differences

Our sample size was chosen to ensure adequate power to detect a statistically significant difference between each of the two mind�body treatment groups and the usual care group, as well as power to detect a statistically significant difference between the two mind�body treatment groups. Because we considered patient activity limitations to be the more consequential of our two co�primary outcome measures, we based our sample size calculations on the modified RDQ [30]. We specified our sample size on the basis of the expected percentage of patients with a clinically meaningful improvement measured with the RDQ at the 26-week assessment (that is, at least 30% relative to baseline) [57].

Because of multiple comparisons, we will use Fisher�s protected least significant difference test [86], first analyzing if there is any significant difference among all three groups (using the omnibus ?2 likelihood ratio test) for each outcome and each time point. If we find a difference, we will then test for pairwise differences between groups. We will need 264 participants (88 in each group) to achieve 90% power to find either mind�body treatment different from usual care on the RDQ. This assumes that 30% of the usual care group and 55% of each mind�body treatment group will have clinically meaningful improvement on the RDQ at 26 weeks, rates of improvement that are similar to those we observed in a similar back pain population in an evaluation of complementary and alternative treatments for back pain [87]. We will have at least 80% power to detect a significant difference between MBSR and CBT on the RDQ if MBSR is at least 20 percentage points more effective than CBT (that is, 75% of the MBSR group versus 55% of the CBT group).

Our other co�primary outcome is the pain bothersomeness rating. With a total sample size of 264 participants, we will have 80% power to detect a difference between a mind�body treatment group and usual care on the bothersomeness rating scale, assuming that 47.5% of usual care and 69.3% of each mind�body treatment group have 30% or more improvement from baseline on the pain bothersomeness rating scale. We will have at least 80% power to detect a significant difference between MBSR and CBT on the bothersomeness rating scale if MBSR is at least 16.7 percentage points more effective than CBT (that is, 87% of the MBSR group versus 69.3% of the CBT group).

When analyzing the primary outcomes as continuous measures, we will have 90% power to detect a 2.4-point difference between usual care and either mind�body treatment on the modified RDQ scale scores and a 1.1-point difference between usual care and either mind�body treatment on the pain bothersomeness rating scale (assumes normal approximation to compare two independent means with equal variances and a two-sided P?=?0.05 significance level with standard deviations of 5.2 and 2.4 for RDQ and pain bothersomeness measures, respectively [88]. Assuming an 11% loss to follow-up (slightly higher than that found in our previous back pain trials), we plan to recruit a sample of 297 participants (99 per group).

Both of the co�primary outcomes will be tested at the P?<?0.05 level at each time point because they address separate scientific questions. Analyses of both outcomes at all follow-up time points will be reported, imposing a more stringent requirement than simply reporting a sole significant outcome.

Statistical Analyses

Primary Analyses

In our comparisons of treatments based on the outcome measures, we will analyze outcomes assessed at all follow-up time points in a single model, adjusting for possible correlation within individuals and treatment group cohorts using generalized estimating equations [89]. Because we cannot reasonably make an assumption regarding constant or linear group differences over time, we will include an interaction term between treatment groups and time points. We plan to adjust for baseline outcome values, sex and age, as well as other baseline characteristics found to differ significantly by treatment group or follow-up outcomes, to improve precision and power of our statistical tests. We will conduct the following set of analyses for both the continuous outcome score and the binary outcome (clinically significant change from baseline), including all follow-up time points (4, 8, 26 and 52 weeks). The MBSR treatment will be deemed successful only if the 26-week time point comparisons are significant. The other time points will be considered secondary evaluations.

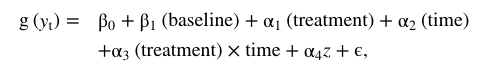

We will use an intent-to-treat approach in all analyses; that is, the assessment of individuals will be analyzed by randomized group, regardless of participation in any classes. This analysis minimizes biases that often occur when participants who do not receive the assigned treatments are excluded from analysis. The regression model will be in the following general form:

where yt is the response at follow-up time t, baseline is the prerandomization value of the outcome measure, treatment includes dummy variables for the MBSR and CBT groups, time is a series of dummy variables indicating the follow-up times and z is a vector of covariates representing other variables adjusted for. (Note that ?1, ?2, ?3 and ?4 are vectors.) The referent group in this model is the usual care group. For binary and continuous outcomes, we will use appropriate link functions (for example, logit for binary). For each follow-up time point at which the omnibus ?2 test is statistically significant, we will go on to test whether there is a difference between MBSR and usual care to address aim 1 and a difference between MBSR and CBT to address aim 2. We will also report the comparison of CBT to usual care. When determining whether MBSR is an effective treatment for back pain, we will require that aim 1, the comparison of MBSR to usual care, must be observed.

On the basis of our previous back pain trials, we expect at least an 89% follow-up and, if that holds true, our primary analysis will be a complete case analysis, including all observed follow-up outcomes. However, we will adjust for all baseline covariates that are predictive of outcome, their probability of being missing and differences between treatment groups. By adjusting for these baseline covariates, we assume that the missing outcome data in our model are missing at random (given that baseline data are predictive of missing data patterns) instead of missing completely at random. We will also conduct sensitivity analysis using an imputation method for nonignorable nonresponses to evaluate whether our results are robust enough to compensate for different missing data assumptions [90].

Mediator Analyses If MBSR or CBT is found to be effective (relative to usual care and/or to each other) in improving either primary outcome at 26 or 52 weeks, we will move to aim 3 to identify the mediators of the effects of MBSR and group CBT on the RDQ and pain bothersomeness scale. We will perform the series of mediation analyses separately for the two primary outcomes (RDQ and pain bothersomeness scale scores) and for each separate treatment comparator of interest (usual care versus CBT, usual care versus MBSR and CBT versus MBSR). We will conduct separate mediator analyses for the 26- and 52-week outcomes (if MBSR or CBT is found to be effective at those time points).

Next, we describe in detail the mediator analysis for the 26-week time point. A similar analysis will be conducted for the 52-week time point. We will apply the framework of the widely used approach of Baron and Kenny [91]. Once we have demonstrated the association between the treatment and the outcome variable (the �total effect� of the treatment on the outcome), the second step will be to demonstrate the association between the treatment and each putative mediator. We will construct a regression model for each mediator with the 4- or 8-week score of the mediator as the dependent variable and the baseline score of the mediator and treatment indicator as independent variables. We will conduct this analysis for each potential mediator and will include as potential mediators in the following step only those that have a P-value ?0.10 for the relationship with the treatment. The third step will be to demonstrate the reduction of the treatment effect on the outcome after removing the effect of the mediators. We will construct a multimediator inverse probability weighted (IPW) regression model [92]. This approach will allow us to estimate the direct effects of treatment after rebalancing the treatment groups with respect to the mediators. Specifically, we will first model the probability of the treatment effects, given the mediators (that is, all mediators that were found to be associated with treatment in step 2), using logistic regression and adjusting for potential baseline confounders. Using this model, we will obtain the estimated probability that each person received the observed treatment, given the observed mediator value. We will then use an IPW regression analysis to model the primary outcomes on treatment status while adjusting for the baseline levels of the outcome and mediator. Comparing the weighted model with the unweighted model will allow us to estimate how much of the direct effect of treatment on the associated outcome can be explained by each potential mediator. The inclusion in step 3 of all mediators found to be significant in step 2 will enable us to examine whether the specific variables that we hypothesized would differentially mediate the effects of MBSR versus CBT in fact mediate the effects of each treatment independently of the effects of the other �process variables�.

Cost-Effectiveness Analyses

A societal perspective cost�utility analysis (CUA) will be performed to compare the incremental societal costs revealed for each treatment arm (direct medical costs paid by GHC and the participant plus productivity costs) to incremental effectiveness in terms of change in participants� QALYs [93]. This analysis will be possible only for study participants recruited from GHC. This CUA can be used by policymakers concerned with the broad allocation of health-related resources [94,95]. For the payer perspective, direct medical costs (including intervention costs) will be compared to changes in QALYs. This CUA will help us to determine whether it makes economic sense for MBSR to be a reimbursed service among this population. A bootstrap methodology will be used to estimate confidence intervals [96]. In secondary analyses conducted to assess the sensitivity of the results to different cost outcome definitions, such as varying assumptions of wage rates used to value productivity and the inclusion of non-back-related health-care resource utilization [97] in the total cost amounts, will also be considered. In cost-effectiveness analyses, we will use intention to treat and adjust for health-care utilization costs in the one calendar year prior to enrollment and for baseline variables that might be associated with treatment group or outcome, such as medication use, to control for potential confounders. We expect there will be minimal missing data, but sensitivity analyses (as described above for the primary outcomes) will also be performed to assess cost measures.

Dr. Alex Jimenez’s Insight

Stress is the body’s response to physical or psychological pressure. Several factors can trigger stress, which in turn activates the “fight or flight” response, a defense mechanism which prepares the body for perceived danger. When stressed, the sympathetic nervous system becomes stimulated and secretes a complex combination of hormones and chemicals. Short-term stress can be helpful, however long-term stress has been connected to a variety of health issues, including back pain and sciatica symptoms. According to research studies, stress management has become an essential addition for many treatment options because stress reduction may help improve treatment outcome measures. Chiropractic care uses spinal adjustments and manual manipulations together with lifestyle modifications to treat the spine, the root of the nervous system, as well as to promote decreased stress levels through proper nutrition, fitness and sleep.

Discussion

In this trial, we will seek to determine whether an increasingly popular approach for dealing with stress�mindfulness-based stress reduction�is an effective and cost-effective treatment option for persons with chronic back pain. Because of its focus on the mind as well as the body, MBSR has the potential to address some of the psychosocial factors that are important predictors of poor outcomes. In this trial, we will compare the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of MBSR with that of CBT, which has been found to be effective for back pain but is not widely available. The study will also explore psychosocial variables that may mediate the effects of MBSR and CBT on patient outcomes. If MBSR is found to be an effective and cost-effective treatment option for persons with chronic back pain, it will be a valuable addition to the treatment options available for patients with significant psychosocial contributors to this problem.

Trial Status

Recruitment started in August 2012 and was completed in April 2014.

Abbreviations

AE: Adverse event; CAM: Complementary and alternative medicine; CATI: Computer-assisted telephone interview; CBT: Cognitive-behavioral therapy; CLBP: Chronic low back pain; CUA: Cost�utility analysis; DSMB: Data and Safety Monitoring Board; GHC: Group Health Cooperative; ICD-9: International Classification of Diseases Ninth Revision; IPW: Inverse probability weighting; IRB: Institutional Review Board; MBSR: Mindfulness-based stress reduction; NCCAM: National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine; QALY: Quality-adjusted life-year.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors� Contributions

DC and KS conceived of the trial. DC, KS, BB, JT, AC, BS, PH, RD and RH participated in refining the study design and implementation logistics and in the selection of outcome measures. AC developed plans for the statistical analyses. JT and AC developed plans for the mediator analyses. BS, BB and JT developed the materials for the CBT intervention. PH developed plans for the cost-effectiveness analyses. DC drafted the manuscript. All authors participated in the writing of the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) provided funding for this trial (grant R01 AT006226). The design of this trial was reviewed and approved by NCCAM�s Office of Clinical and Regulatory Affairs.

In conclusion, environmental, bodily and emotional stressors can trigger the “fight or flight response” in charge of preparing the the human body for danger. Although stress is essential to increase our performance, chronic stress can have a negative impact in the long-run, manifesting symptoms associated with back pain and sciatica. Chiropractic care utilizes a variety of treatment procedures, along with stress management methods and techniques, to help reduce stress as well as improve and manage symptoms associated with injuries and/or conditions of the musculoskeletal and nervous systems.�Information referenced from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic as well as to spinal injuries and conditions. To discuss the subject matter, please feel free to ask Dr. Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

Curated by Dr. Alex Jimenez

Additional Topics: Back Pain

According to statistics, approximately 80% of people will experience symptoms of back pain at least once throughout their lifetimes. Back pain is a common complaint which can result due to a variety of injuries and/or conditions. Often times, the natural degeneration of the spine with age can cause back pain. Herniated discs occur when the soft, gel-like center of an intervertebral disc pushes through a tear in its surrounding, outer ring of cartilage, compressing and irritating the nerve roots. Disc herniations most commonly occur along the lower back, or lumbar spine, but they may also occur along the cervical spine, or neck. The impingement of the nerves found in the low back due to injury and/or an aggravated condition can lead to symptoms of sciatica.

IMPORTANT TOPIC: EXTRA EXTRA: A Healthier You!

OTHER IMPORTANT TOPICS: EXTRA: Sports Injuries? | Vincent Garcia | Patient | El Paso, TX Chiropractor

Blank

References

1. Luo X, Pietrobon R, Sun SX, Liu GG, Hey L. Estimates and patterns of direct health care expenditures among individuals with back pain in the United States.�Spine (Phila Pa)�2004;29:79�86.�[PubMed]

2. Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, Morganstein D, Lipton R. Lost productive time and cost due to common pain conditions in the US workforce.�JAMA.�2003;290:2443�2454.�[PubMed]

3. Martin BI, Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Turner JA, Comstock BA, Hollingworth W, Sullivan SD. Expenditures and health status among adults with back and neck problems.�JAMA.�2008;299:656�664.�A published erratum appears in�JAMA�2008, 299:2630.�[PubMed]

4. No authors listed. How is your doctor treating you?�Consum Rep.�1995;60(2):81�88.

5. Cherkin DC, MacCornack FA, Berg AO. Managing low back pain�a comparison of the beliefs and behaviors of family physicians and chiropractors.�West J Med.�1988;149:475�480.[PMC free article]�[PubMed]

6. Cherkin DC, MacCornack FA. Patient evaluations of low back pain care from family physicians and chiropractors.�West J Med.�1989;150:351�355.�[PMC free article]�[PubMed]

7. Novy DM, Nelson DV, Francis DJ, Turk DC. Perspectives of chronic pain: an evaluative comparison of restrictive and comprehensive models.�Psychol Bull.�1995;118:238�247.�[PubMed]

8. Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, Casey D, Cross JT Jr, Shekelle P, Owens DK. Clinical Efficacy Assessment Subcommittee of the American College of Physicians; American College of Physicians; American Pain Society Low Back Pain Guidelines Panel. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society.�Ann Intern Med.�2007;147:478�491.�[PubMed]

9. Williams AC, Eccleston C, Morley S. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults.�Cochrane Database Syst Rev.�2012;11:CD007407.�[PubMed]

10. Aggarwal VR, Lovell K, Peters S, Javidi H, Joughin A, Goldthorpe J. Psychosocial interventions for the management of chronic orofacial pain.�Cochrane Database Syst Rev.�2011;11:CD008456.[PubMed]

11. Glombiewski JA, Sawyer AT, Gutermann J, Koenig K, Rief W, Hofmann SG. Psychological treatments for fibromyalgia: a meta-analysis.�Pain.�2010;151:280�295.�[PubMed]

12. Henschke N, Ostelo RW, van Tulder MW, Vlaeyen JW, Morley S, Assendelft WJ, Main CJ. Behavioural treatment for chronic low-back pain.�Cochrane Database Syst Rev.�2010;7:CD002014.[PubMed]

13. Hoffman BM, Papas RK, Chatkoff DK, Kerns RD. Meta-analysis of psychological interventions for chronic low back pain.�Health Psychol.�2007;26:1�9.�[PubMed]

14. Reinier K, Tibi L, Lipsitz JD. Do mindfulness-based interventions reduce pain intensity? A critical review of the literature.�Pain Med.�2013;14:230�242.�[PubMed]

15. Lakhan SE, Schofield KL. Mindfulness-based therapies in the treatment of somatization disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis.�PLoS One.�2013;8:e71834.�[PMC free article]�[PubMed]

16. Grossman P, Niemann L, Schmidt S, Walach H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: a meta-analysis.�J Psychosom Res.�2004;57:35�43.�[PubMed]

17. Fjorback LO, Arendt M, Ornb�l E, Fink P, Walach H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials.�Acta Psychiatr Scand.�2011;124:102�119.�[PubMed]

18. Merkes M. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for people with chronic diseases.�Aust J Prim Health.�2010;16:200�210.�[PubMed]

19. Goyal M, Singh S, Sibinga EM, Gould NF, Rowland-Seymour A, Sharma R, Berger Z, Sleicher D, Maron DD, Shihab HM, Ranasinghe PD, Linn S, Saha S, Bass EB, Haythornthwaite JA. Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis.�JAMA Intern Med.�2014;174:357�368.�[PMC free article]�[PubMed]

20. Chiesa A, Serretti A. Mindfulness-based interventions for chronic pain: a systematic review of the evidence.�J Altern Complement Med.�2011;17:83�93.�[PubMed]

21. Carmody J, Baer RA. Relationships between mindfulness practice and levels of mindfulness, medical and psychological symptoms and well-being in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program.�J Behav Med.�2008;31:23�33.�[PubMed]

22. Nykl�cek I, Kuijpers KF. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention on psychological well-being and quality of life: Is increased mindfulness indeed the mechanism?�Ann Behav Med.�2008;35:331�340.�[PMC free article]�[PubMed]

23. Shapiro SL, Carlson LE, Astin JA, Freedman B. Mechanisms of mindfulness.�J Clin Psychol.�2006;62:373�386.�[PubMed]

24. Baer RA. Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: a conceptual and empirical review.�Clin Psychol Sci Pract.�2003;10:125�143.

25. Cramer H, Haller H, Lauche R, Dobos G. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for low back pain: a systematic review.�BMC Complement Altern Med.�2012;12:162.�[PMC free article]�[PubMed]

26. Plews-Ogan M, Owens JE, Goodman M, Wolfe P, Schorling J. A pilot study evaluating mindfulness-based stress reduction and massage for the management of chronic pain.�J Gen Intern Med.�2005;20:1136�1138.�[PMC free article]�[PubMed]

27. Esmer G, Blum J, Rulf J, Pier J. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for failed back surgery syndrome: a randomized controlled trial.�J Am Osteopath Assoc.�2010;110:646�652.�Published errata appear in J Am Osteopath Assoc 2011, 111:3 and J Am Osteopath Assoc 2011, 111:424. The corrections are incorporated into the online version of the article.�[PubMed]

28. Morone NE, Rollman BL, Moore CG, Li Q, Weiner DK. A mind�body program for older adults with chronic low back pain: results of a pilot study.�Pain Med.�2009;10:1395�1407.�[PMC free article][PubMed]

29. Morone NE, Greco CM, Weiner DK. Mindfulness meditation for the treatment of chronic low back pain in older adults: a randomized controlled pilot study.�Pain.�2008;134:310�319.�[PMC free article][PubMed]

30. Patrick DL, Deyo RA, Atlas SJ, Singer DE, Chapin A, Keller RB. Assessing health-related quality of life in patients with sciatica.�Spine.�1995;20:1899�1908.�[PubMed]

31. Roland M, Morris R. A study of the natural history of low-back pain. Part II: development of guidelines for trials of treatment in primary care.�Spine (Phila Pa 1976)�1983;8:145�150.�[PubMed]

32. Kabat-Zinn J. An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results.�Gen Hosp Psychiatry.�1982;4:33�47.�[PubMed]

33. Kabat-Zinn J.�Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness.�New York: Random House; 2005.

34. Kabat-Zinn J, Chapman-Waldrop A. Compliance with an outpatient stress reduction program: rates and predictors of program completion.�J Behav Med.�1988;11:333�352.�[PubMed]

35. Blacker M, Meleo-Meyer F, Kabat-Zinn J, Santorelli SF.�Stress Reduction Clinic Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) Curriculum Guide.�Worcester, MA: Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care, and Society, Division of Preventive and Behavioral Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School; 2009.

36. Turner JA, Romano JM. In:�Bonica�s Management of Pain.�3. Loeser JD, Butler SH, Chapman CR, Turk DC, editor. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain; pp. 1751�1758.

37. Nicholas MK, Asghari A, Blyth FM, Wood BM, Murray R, McCabe R, Brnabic A, Beeston L, Corbett M, Sherrington C, Overton S. Self-management intervention for chronic pain in older adults: a randomised controlled trial.�Pain.�2013;154:824�835.�[PubMed]

38. Lamb SE, Hansen Z, Lall R, Castelnuovo E, Withers EJ, Nichols V, Potter R, Underwood MR. Back Skills Training Trial investigators. Group cognitive behavioural treatment for low-back pain in primary care: a randomised controlled trial and cost-effectiveness analysis.�Lancet.�2010;375:916�923.�[PubMed]

39. Turner JA. Comparison of group progressive-relaxation training and cognitive-behavioral group therapy for chronic low back pain.�J Consult Clin Psychol.�1982;50:757�765.�[PubMed]

40. Turner JA, Clancy S. Comparison of operant behavioral and cognitive-behavioral group treatment for chronic low back pain.�J Consult Clin Psychol.�1988;56:261�266.�[PubMed]

41. Turner JA, Mancl L, Aaron LA. Short- and long-term efficacy of brief cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with chronic temporomandibular disorder pain: a randomized, controlled trial.�Pain.�2006;121:181�194.�[PubMed]

42. Ehde DM, Dillworth TM, Turner JA.�Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Manual for the Telephone Intervention for Pain Study (TIPS)�Seattle: University of Washington; 2012.

43. Turk DC, Winter F.�The Pain Survival Guide: How to Reclaim Your Life.�Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005.

44. Thorn BE.�Cognitive Therapy for Chronic Pain: A Step-by-Step Guide.�New York: Guilford Press; 2004.

45. Otis JD.�Managing Chronic Pain: A Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Approach (Therapist Guide)�New York: Oxford University Press; 2007.

46. Vitiello MV, McCurry SM, Shortreed SM, Balderson BH, Baker LD, Keefe FJ, Rybarczyk BD, Von Korff M. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for comorbid insomnia and osteoarthritis pain in primary care: the lifestyles randomized controlled trial.�J Am Geriatr Soc.�2013;61:947�956.[PMC free article]�[PubMed]

47. Caudill MA.�Managing Pain Before It Manages You.�New York: Guilford Press; 1994.

48. Bombardier C. Outcome assessments in the evaluation of treatment of spinal disorders: introduction.�Spine (Phila Pa 1976)�2000;25:3097�3099.�[PubMed]

49. Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, Haythornthwaite JA, Jensen MP, Katz NP, Kerns RD, Stucki G, Allen RR, Bellamy N, Carr DB, Chandler J, Cowan P, Dionne R, Galer BS, Hertz S, Jadad AR, Kramer LD, Manning DC, Martin S, McCormick CG, McDermott MP, McGrath P, Quessy S, Rappaport BA, Robbins W, Robinson JP, Rothman M, Royal MA, Simon L. et al. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations.�Pain.�2005;113:9�19.[PubMed]

50. Roland M, Fairbank J. The Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire and the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire.�Spine (Phila Pa 1976)�2000;25:3115�3124.�A published erratum appears in�Spine (Phila Pa 1976)�2001, 26:847.�[PubMed]

51. Jensen MP, Strom SE, Turner JA, Romano JM. Validity of the Sickness Impact Profile Roland Scale as a measure of dysfunction in chronic pain patients.�Pain.�1992;50:157�162.�[PubMed]

52. Underwood MR, Barnett AG, Vickers MR. Evaluation of two time-specific back pain outcome measures.�Spine (Phila Pa 1976)�1999;24:1104�1112.�[PubMed]

53. Beurskens AJ, de Vet HC, K�ke AJ. Responsiveness of functional status in low back pain: a comparison of different instruments.�Pain.�1996;65:71�76.�[PubMed]

54. Dunn KM, Croft PR. Classification of low back pain in primary care: using �bothersomeness� to identify the most severe cases.�Spine (Phila Pa 1976)�2005;30:1887�1892.�[PubMed]

55. Jensen MP, Karoly P. In:�Handbook of Pain Assessment.�2. Turk DC, Melzack R, editor. New York: Guilford Press; 2001. Self-report scales and procedures for assessing pain in adults; pp. 15�34.

56. Farrar JT, Young JP Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole RM. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale.�Pain.�2001;94:149�158.[PubMed]

57. Ostelo RW, Deyo RA, Stratford P, Waddell G, Croft P, Von Korff M, Bouter LM, de Vet HC. Interpreting change scores for pain and functional status in low back pain: towards international consensus regarding minimal important change.�Spine (Phila Pa 1976)�2008;33:90�94.�[PubMed]

58. Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population.�J Affect Disord.�2009;114:163�173.�[PubMed]

59. L�we B, Un�tzer J, Callahan CM, Perkins AJ, Kroenke K. Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9.�Med Care.�2004;42:1194�1201.�[PubMed]

60. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure.�J Gen Intern Med.�2001;16:606�613.�[PMC free article]�[PubMed]

61. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Monahan PO, L�we B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection.�Ann Intern Med.�2007;146:317�325.�[PubMed]

62. Skapinakis P. The 2-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale had high sensitivity and specificity for detecting GAD in primary care.�Evid Based Med.�2007;12:149.�[PubMed]

63. Von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, Dworkin SF. Grading the severity of chronic pain.�Pain.�1992;50:133�149.�[PubMed]

64. Von Korff M. In:�Handbook of Pain Assessment.�2. Turk DC, Melzack R, editor. New York: Guilford Press; 2001. Epidemiological and survey methods: assessment of chronic pain; pp. 603�618.

65. Guy W, National Institute of Mental Health (US), Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Early Clinical Drug Evaluation Program.�ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology (Revised 1976)�Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, National Institute of Mental Health, Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research Programs; 1976.

66. Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity.�Med Care.�1996;34:220�233.�[PubMed]

67. Brazier JE, Roberts J. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-12.�Med Care.�2004;42:851�859.�[PubMed]

68. Bohlmeijer E, ten Klooster PM, Fledderus M, Veehof M, Baer R. Psychometric properties of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire in depressed adults and development of a short form.�Assessment.�2011;18:308�320.�[PubMed]

69. Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, Toney L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness.�Assessment.�2006;13:27�45.�[PubMed]

70. Baer RA, Smith GT, Lykins E, Button D, Krietemeyer J, Sauer S, Walsh E, Duggan D, Williams JM. Construct validity of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples.�Assessment.�2008;15:329�342.�[PubMed]

71. McCracken LM, Vowles KE, Eccleston C. Acceptance of chronic pain: component analysis and a revised assessment method.�Pain.�2004;107:159�166.�[PubMed]

72. Vowles KE, McCracken LM, McLeod C, Eccleston C. The Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire: confirmatory factor analysis and identification of patient subgroups.�Pain.�2008;140:284�291.[PubMed]

73. Nicholas MK. The Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire: taking pain into account.�Eur J Pain.�2007;11:153�163.�[PubMed]

74. Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM, Lawler BK. Relationship of pain-specific beliefs to chronic pain adjustment.�Pain.�1994;57:301�309.�[PubMed]

75. Jensen MP, Karoly P. Pain-specific beliefs, perceived symptom severity, and adjustment to chronic pain.�Clin J Pain.�1992;8:123�130.�[PubMed]

76. Strong J, Ashton R, Chant D. The measurement of attitudes towards and beliefs about pain.�Pain.�1992;48:227�236.�[PubMed]

77. Sullivan MJ, Thorn B, Haythornthwaite JA, Keefe F, Martin M, Bradley LA, Lefebvre JC. Theoretical perspectives on the relation between catastrophizing and pain.�Clin J Pain.�2001;17:52�64.�[PubMed]

78. Sullivan MJ, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: development and validation.�Psychol Assess.�1995;7:524�532.

79. Osman A, Barrios FX, Gutierrez PM, Kopper BA, Merrifield T, Grittmann L. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: further psychometric evaluation with adult samples.�J Behav Med.�2000;23:351�365.�[PubMed]

80. Lam� IE, Peters ML, Kessels AG, Van Kleef M, Patijn J. Test�retest stability of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale and the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia in chronic pain over a longer period of time.�J Health Psychol.�2008;13:820�826.�[PubMed]

81. Romano JM, Jensen MP, Turner JA. The Chronic Pain Coping Inventory-42: reliability and validity.�Pain.�2003;104:65�73.�[PubMed]

82. Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM, Strom SE. The Chronic Pain Coping Inventory: development and preliminary validation.�Pain.�1995;60:203�216.�[PubMed]

83. Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument.�Pharmacoeconomics.�1993;4:353�365.�[PubMed]

84. Brazier J, Usherwood T, Harper R, Thomas K. Deriving a preference-based single index from the UK SF-36 Health Survey.�J Clin Epidemiol.�1998;51:1115�1128.�[PubMed]

85. Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P. CONSORT Group. Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaboration.�Ann Intern Med.�2008;148:295�309.�[PubMed]

86. Levin J, Serlin R, Seaman M. A controlled, powerful multiple-comparison strategy for several situations.�Psychol Bull.�1994;115:153�159.

87. Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Avins AL, Erro JH, Ichikawa L, Barlow WE, Delaney K, Hawkes R, Hamilton L, Pressman A, Khalsa PS, Deyo RA. A randomized controlled trial comparing acupuncture, simulated acupuncture, and usual care for chronic low back pain.�Arch Intern Med.�2009;169:858�866.�[PMC free article]�[PubMed]

88. Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Kahn J, Wellman R, Cook AJ, Johnson E, Erro J, Delaney K, Deyo RA. A comparison of the effects of 2 types of massage and usual care on chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled trial.�Ann Intern Med.�2011;155:1�9.�[PMC free article]�[PubMed]

89. Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes.�Biometrics.�1986;42:121�130.�[PubMed]

90. Wang M, Fitzmaurice GM. A simple imputation method for longitudinal studies with non-ignorable non-responses.�Biom J.�2006;48:302�318.�[PubMed]

91. Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations.�J Pers Soc Psychol.�1986;51:1173�1182.�[PubMed]

92. VanderWeele TJ. Marginal structural models for the estimation of direct and indirect effects.�Epidemiology.�2009;20:18�26.�A published erratum appears in�Epidemiology�2009, 20:629.[PubMed]

93. Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, O�Brien BJ, Stoddart GL.�Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes.�3. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005.

94. Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russel LB, Weinstein MC, editor.�Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine: Report of the Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine.�Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1996.

95. Siegel JE, Weinstein MC, Russell LB, Gold MR. Recommendations for reporting cost-effectiveness analyses.�JAMA.�1996;276:1339�1341.�[PubMed]

96. Thompson SG, Barber JA. How should cost data in pragmatic randomised trials be analysed?�BMJ.�2000;320:1197�1200.�[PMC free article]�[PubMed]

97. Briggs AH. Handling uncertainty in cost-effectiveness models.�Pharmacoeconomics.�2000;17:479�500.�[PubMed]

Investigate why the source process may be the same for both conditions in some.

Investigate why the source process may be the same for both conditions in some. Sciatica cases where constipation is also present involves the nerve roots in the lower spinal regions. These types of symptomatic expressions will be blamed on a variety of structural abnormalities in the lumbosacral region, which include degenerative disc disease, herniated discs and spinal osteoarthritis.

Sciatica cases where constipation is also present involves the nerve roots in the lower spinal regions. These types of symptomatic expressions will be blamed on a variety of structural abnormalities in the lumbosacral region, which include degenerative disc disease, herniated discs and spinal osteoarthritis.