Neurophysiology Of Pain | El Paso, TX. | Part I

Neurophysiology of pain: Pain�defined is the unpleasant sensation that accompanies injury or near injury to tissues, though it can also occur in the absence of such damage if the nociception system is not functioning. Nociception means the system that carries pain signals of injury from the tissues. This is the physiological incident that comes with pain.

Contents

Neurophysiology Of Pain

Objectives

- Basics of the nervous system

- Synaptic function

- Nerve impulses

- Transduction of peripheral painful stimuli

- Central pathways

- Central Sensitization

- PeripheralSensitization

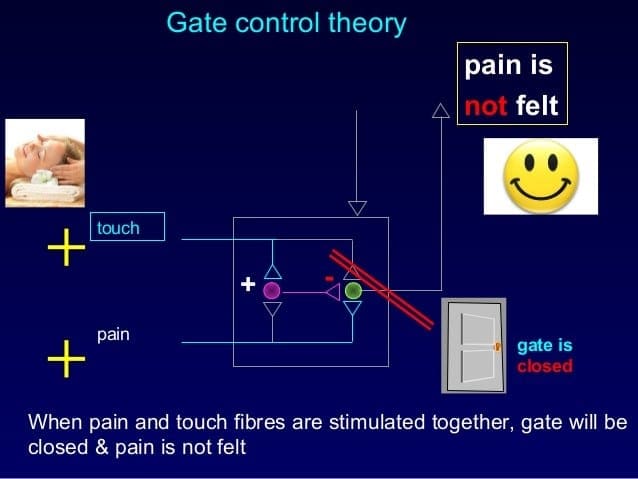

- Control or modulation of pain signals

- Pathophysiology of pain signaling pathway

Definition Of Pain

“Pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage”.

(The International Association for the Study of Pain)

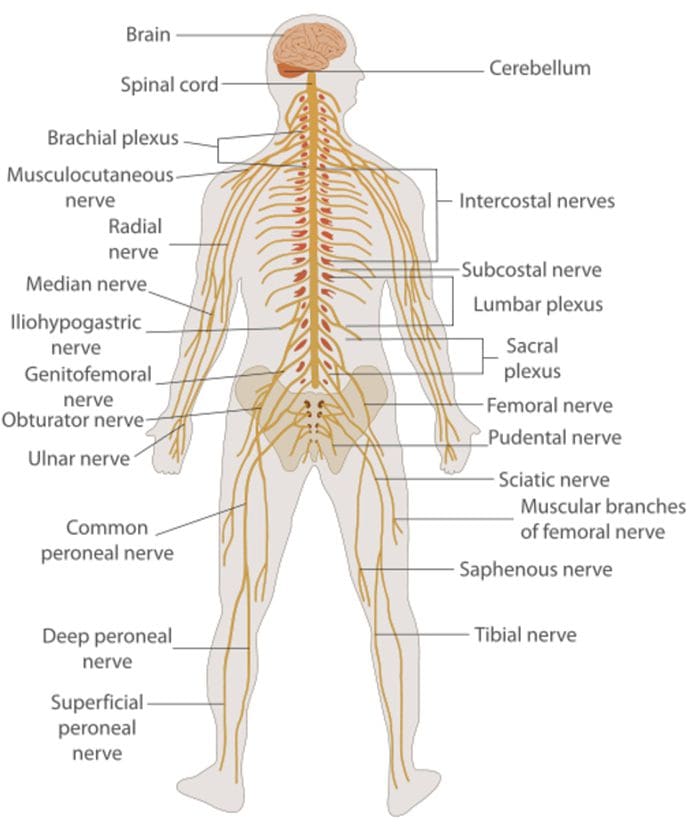

The Nervous System

- It is important to know the basic structure of the nervous system.

- This will help in:

� Understanding the mechanism by which nociceptive signals are produced.

� Know the different regions of the nervous system involved in processing these signals.

� Learn how the different medications and treatment for pain management work.

Nervous System

Central nervous system (CNS)

- Brain and Spinal Cord

Peripheral Nervous System (PNS)

- Nerve fibers go to all parts of the body.

- Send signals to the different tissues and send signals back to the CNS.

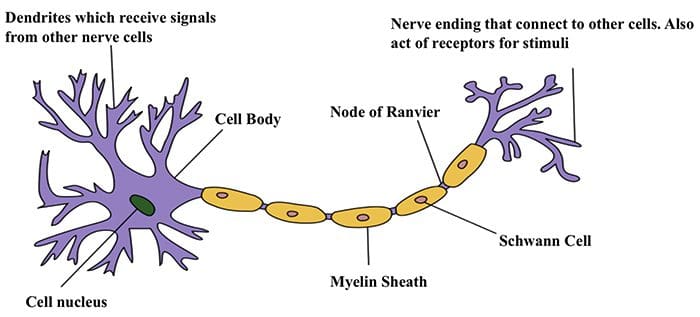

Nerve Cells

- The nervous system is made up of nerve cells which send long processes (axons) to make contact with other cells.

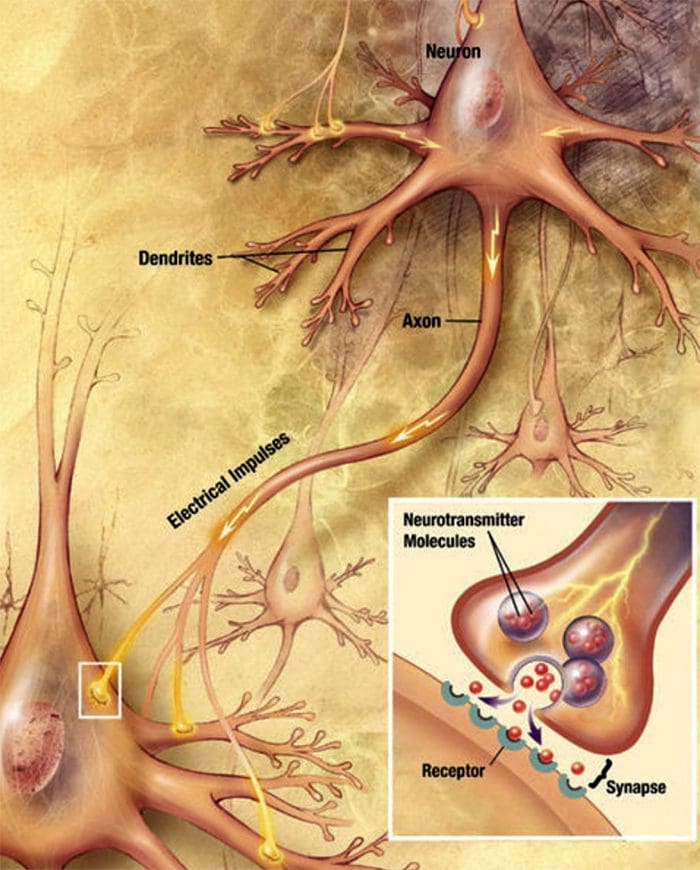

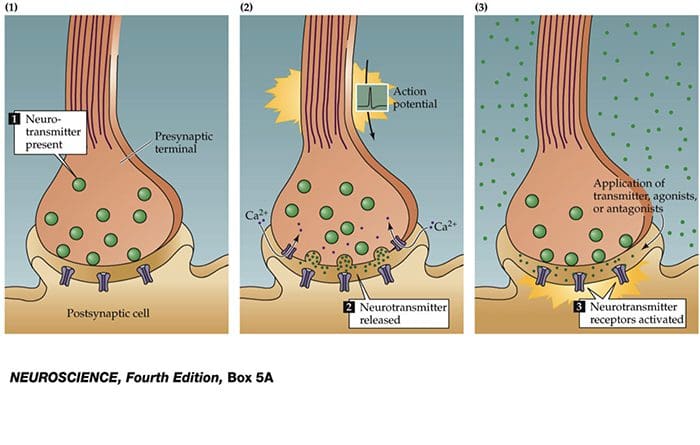

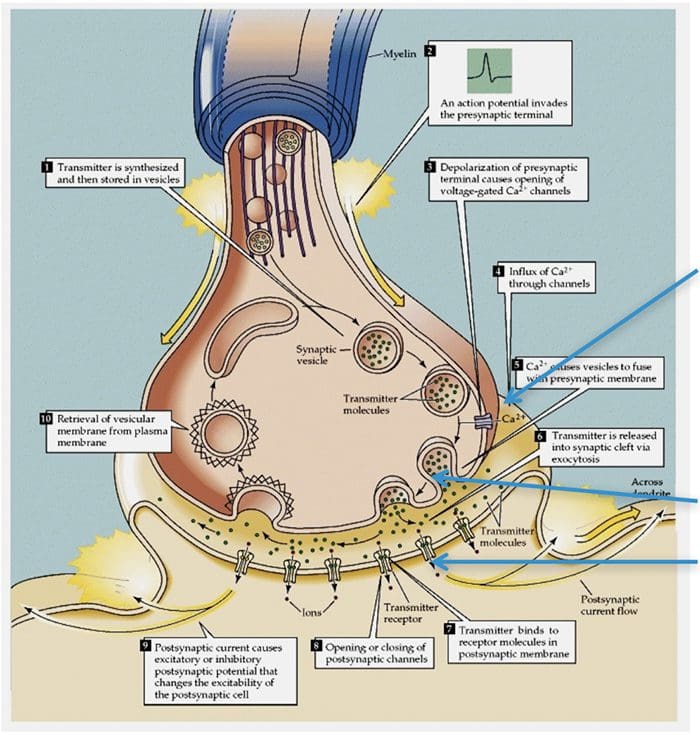

Nerve Cell-To-Nerve Cell Communication

Nerve Cell-To-Nerve Cell Communication

Nerve cells communicate with other cells by releasing a chemical from the nerve endings � Neurotransmitters

Nerve cells communicate with other cells by releasing a chemical from the nerve endings � Neurotransmitters

Basic Steps In Synaptic Transmission

Synaptic Transmission

Synaptic Transmission

Steps in the passage of signal from one nerve cell to other.

- Drugs are used to block the transmission of signals from one nerve cell to other.

These drugs can effect:

- Ca2+ ion channel to prevent Ca2+ inflow which is essential for neurotransmitter (NT) release, e.g., the action of gabapentin.

- Release of NT.

- Prevent NT from binding to its receptor so stop further transmission of the signal.

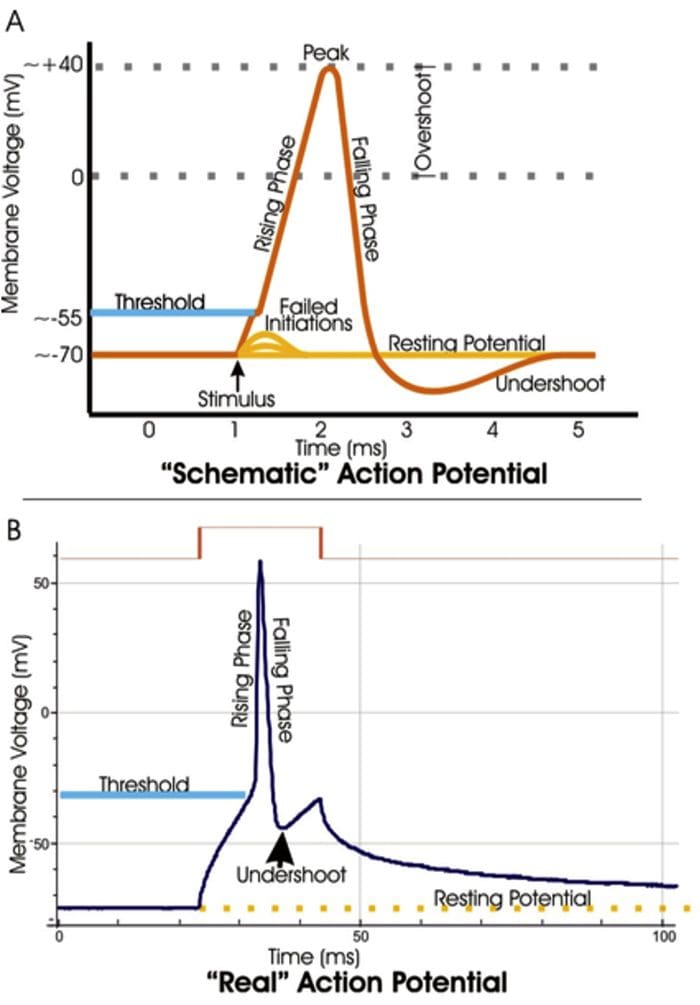

Electrical Impulse

- Signals move along a nerve process (axon) as a wave of membrane depolarization called the Action Potential.

- The inside of all nerve cells has a negative electrical potential of around � 60 mV.

- When stimulated this negative electrical potential becomes positive and then negative again in milliseconds.

- The action potential moves along the nerve process (axon) to the nerve ending where it cause release of NT.

Action Potential

- When there is no stimulation the membrane potential is at its Resting Potential.

- When stimulated, channels in the nerve membrane open allowing the flow of sodium ions (Na+) or calcium ions (Ca2+) into the nerve or cell. This makes the inside less negative and in fact positive -the peak of the action potential (+40 mV).

- These channels than close and by the opening of K+ channels the membrane potential returns to its resting level.

Stopping Action Potentials To Stop Nociceptive Stimuli

- Nociceptive stimuli are those that will create a sensation of pain after they are processed in the CNS.

- Nociceptive signals can be prevented from reaching the CNS by blocking the action of the channels that control the movement of ions across the nerve membrane.

- A number of anesthetic agents stop Na+ channel from working and hence stop the generation of actions potentials and transmission of signals to the CNS.

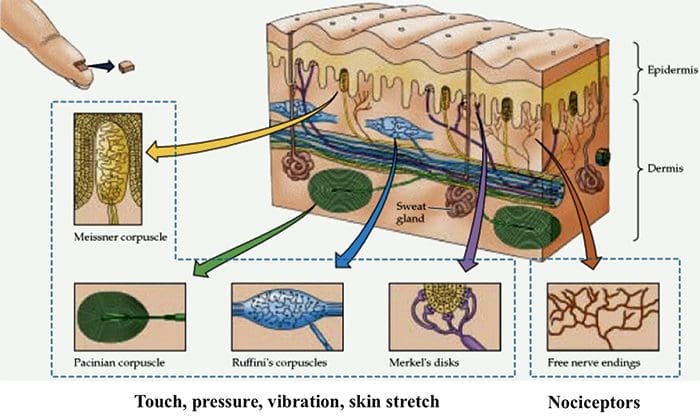

Sensory Systems

The sensory system that can be divided into two divisions:

- A Sensory System that transmits innocuous stimuli such as touch, pressure, warmth.

- A System that transmits stimuli that indicate that tissues have been damaged = nociceptive .

These two systems have different receptors and pathways in the PNS & CNS

Skin Receptors

Nociceptors

- Nociceptors are free nerve endings that respond to stimuli that can cause tissue damage or when tissue damage has taken place.

- Present in membrane of free nerve endings are receptors (protein molecules) whose activity changes in the presence of painful stimuli.

- (Note the use of the same term receptor is used for cell or organs or molecules that involved in transduction of a stimuli.)

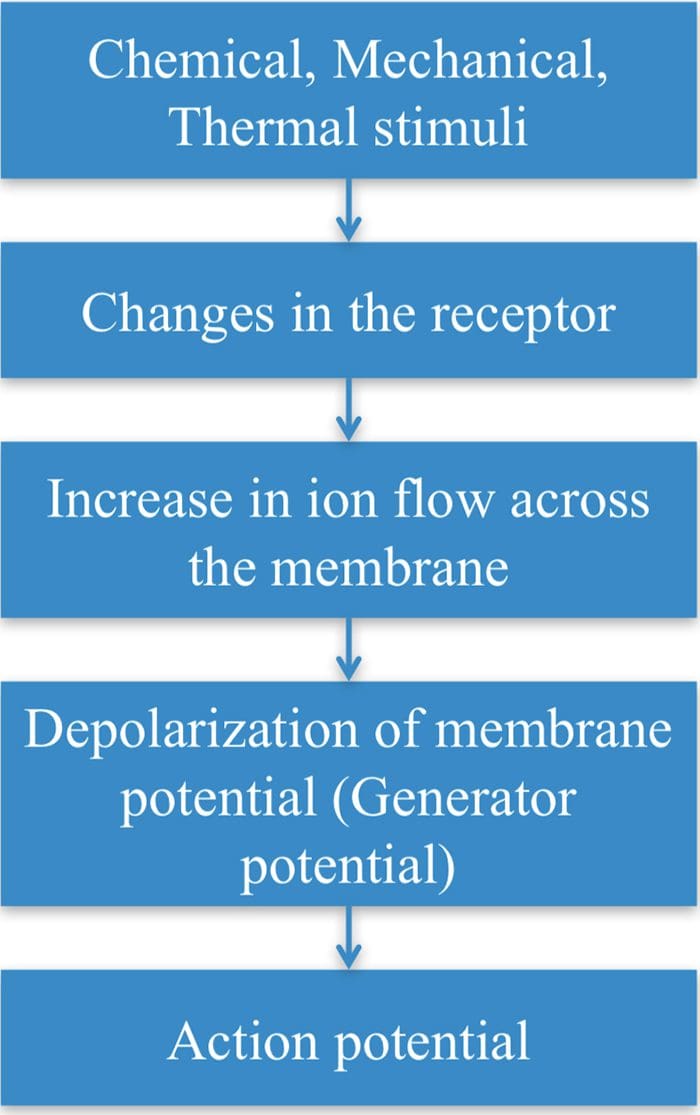

Transduction

- Transduction is the process of converting the stimuli into a nerve impulse.

- For this to occur the flow of ions across the nerve membrane has to change to allow entry of either Na+ or Ca2+ ions to cause depolarization of the membrane potential.

- This involves a receptor molecule that either directly or indirectly opens the ion channels.

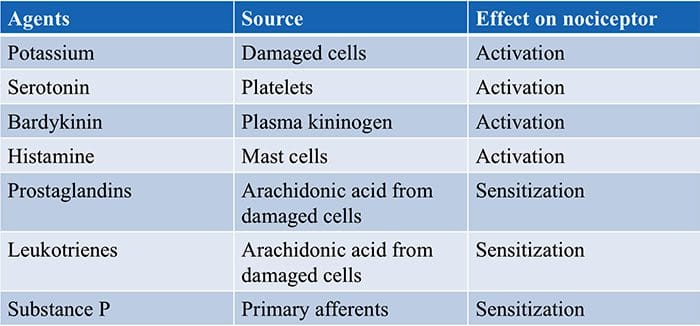

Chemical Agents…

… which can cause the membrane potential at the free nerve ending (nociceptor) to produce an action potential.

Fields HL. 1987. Pain. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Fields HL. 1987. Pain. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Summary Of Transduction Process At The Periphery

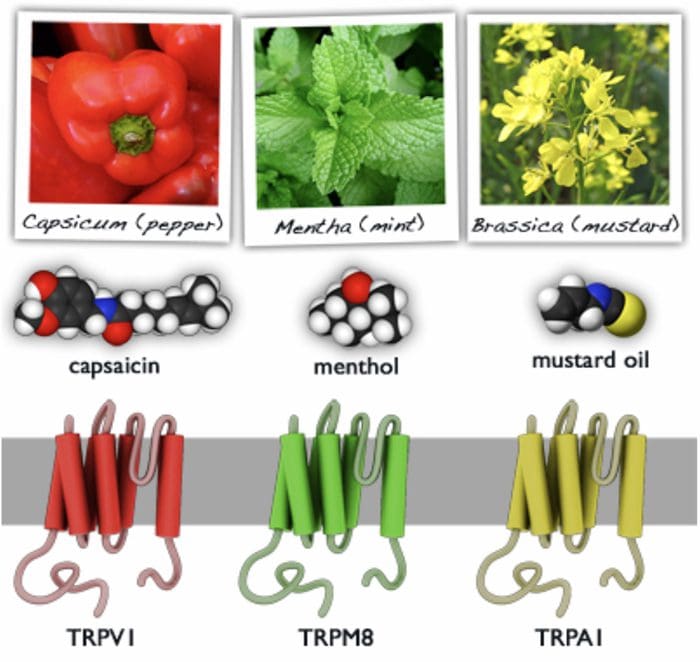

TRP Channels

TRP Channels

- Many stimuli � mechanical, chemical and thermal � give rise to painful sensation making transduction a complex process.

- Recently receptor molecules have been identified�� Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) channels � that respond to a number of strong stimuli.

- TRP receptors are also involved in transmitting the burning sensation of chili pepper.

- In time, drugs that act on these receptors will be developed to control pain.

Different TRP Channels

- Capsasin, the active ingredient in chili pepper, is used in patches for relief of pain.

- Menthol and peppermint gels are used to relieve muscle pain.

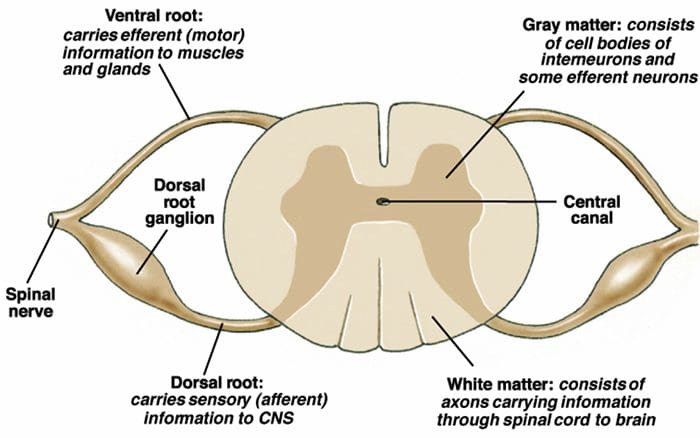

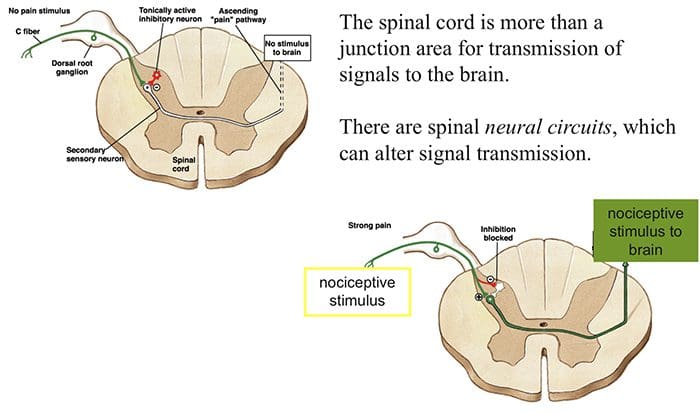

Motor Output & Sensory Input To Spinal Cord

- Sensory nerves have their cell body outside the spinal cord in the dorsal root ganglia ( = 1st order neurons).

- One process goes to the periphery, the other goes to the spinal cord where it makes synaptic contact with nerve cells in the spinal cord ( = 2nd order neurons).

- The 2nd order neuron sends processes to other nerve cells in the spinal cord and to the brain.

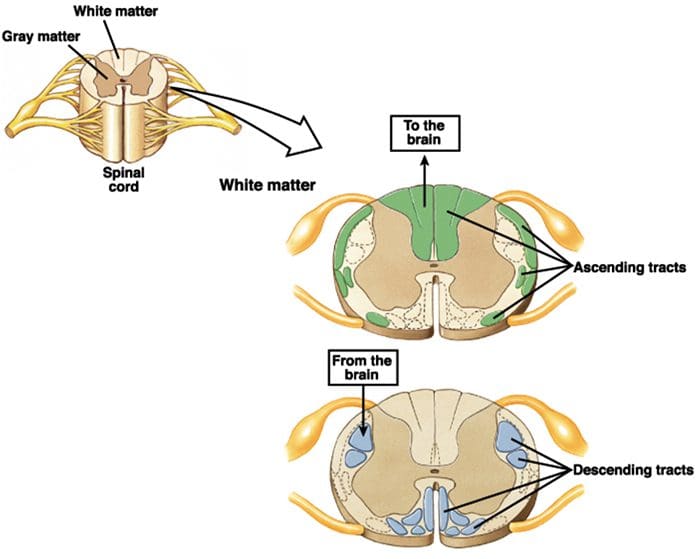

2nd Order Nerve Cells Send Nerve Fibers In The Spinal Cord White Matter

Transmission Of Nociceptive Signals From The Periphery To The Brain

Silverthorn

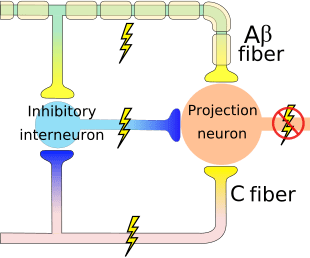

A Delta (?) & C Nerve Fibers

Nerve fibers are classified according to the:

� (1) diameter of the nerve fiber and

� (2) whether myelinated or not.

- A? and C nerve fiber endings respond to strong stimuli.

- A? are myelinated and C are not.

- Action potentials are transmitted 10 times faster in the A?

(20 m/sec) fibers than in C fibers (2 m/sec).

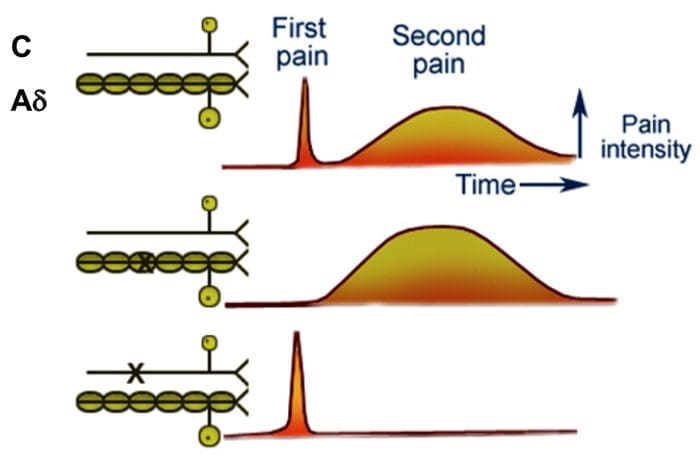

A? & C fibers

- A? fibers respond mainly to mechanical and mechno-thermal stimuli.

- C fibers are polymodal, i.e. the nerve ending responds to several modalities � thermal, mechanical and chemical

- This polymodal ability is due to the presence of different receptor molecules in a single nerve ending.

Fast & Slow Pain

- Most people when they are hit by an object or scrape their skin, feel a sharp first pain (epicritic) followed by a second dull, aching, longer lasting pain (protopathic).

- The first fast pain is transmitted by the myelinated A? fibers and the second pain by the unmyelinated C fibers.

Central Pain Pathways

Nociceptive signals are sent to the spinal cord and then to different parts of the brain where sensation of pain is processed.

There are a pathways/regions for assessing the:

- Location, intensity, and quality of the noxious stimuli

- Unpleasantness and autonomic activation (fight-or-flight response, depression, anxiety).

We are blessed to present to you�El Paso�s Premier Wellness & Injury Care Clinic.

We are blessed to present to you�El Paso�s Premier Wellness & Injury Care Clinic.

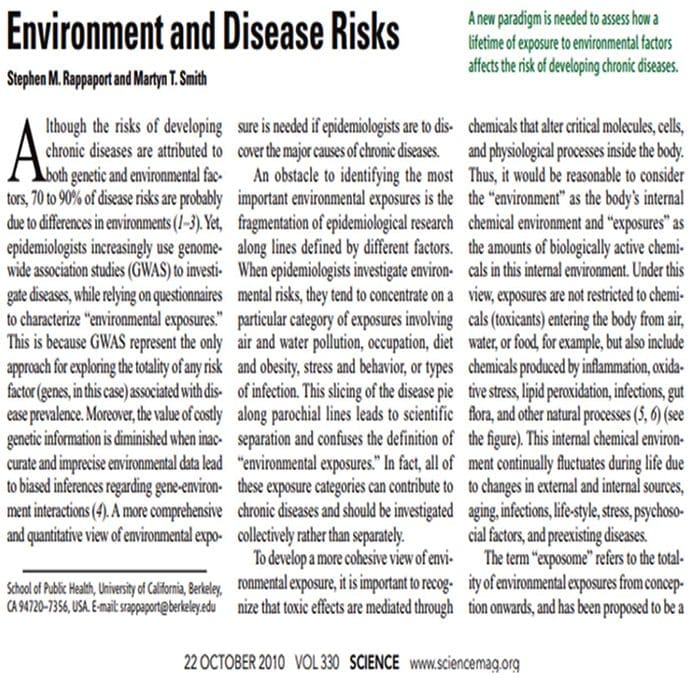

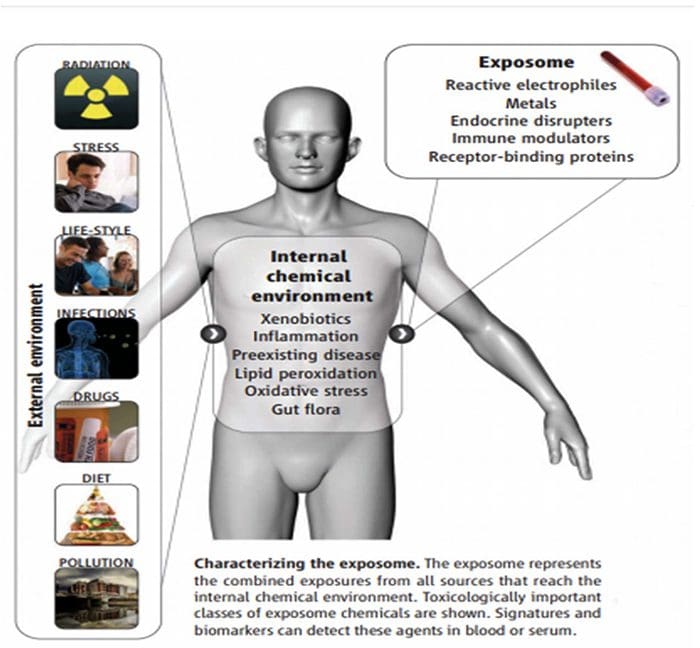

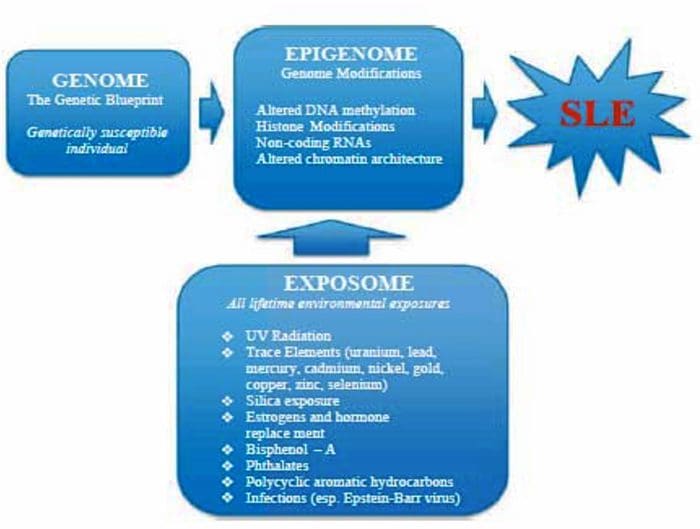

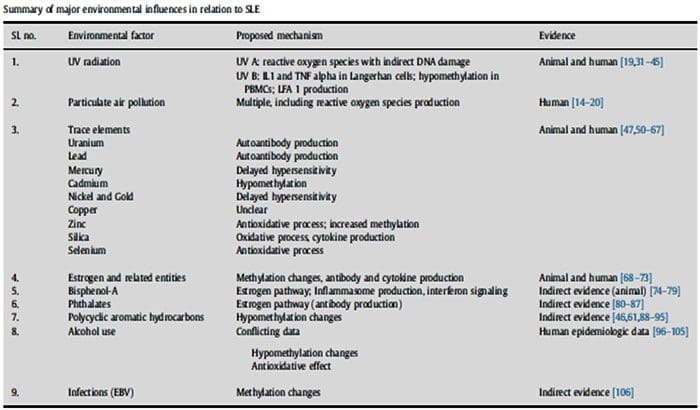

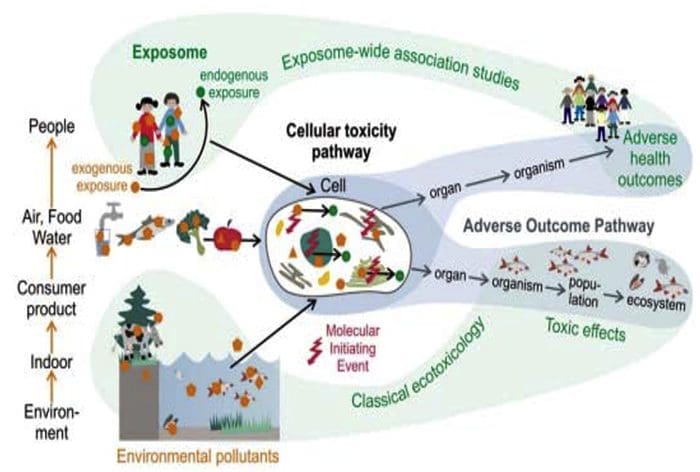

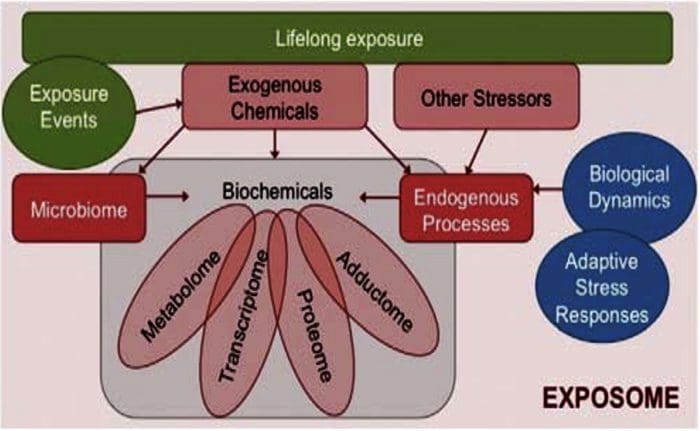

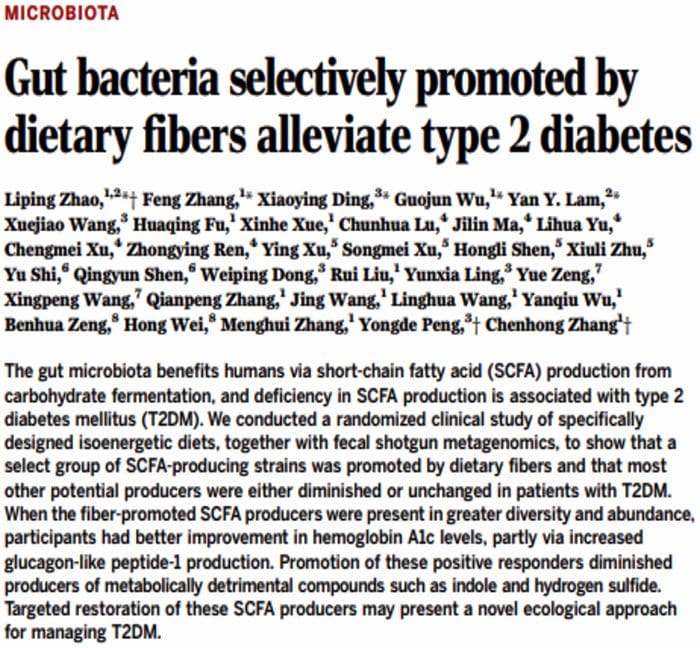

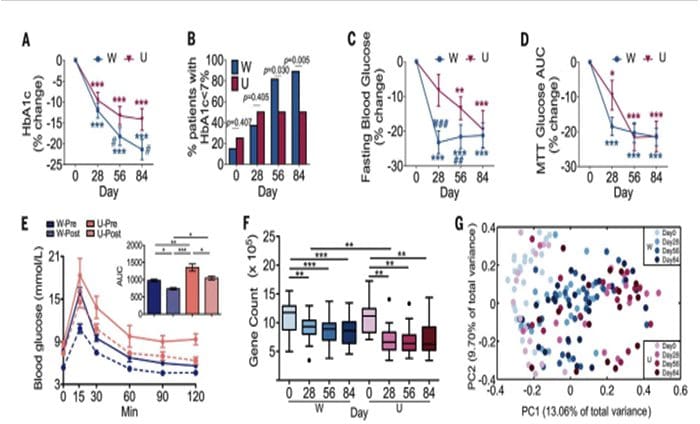

The Ecology Of The Exposome

The Ecology Of The Exposome Exposome & The Alteration Of �Self�

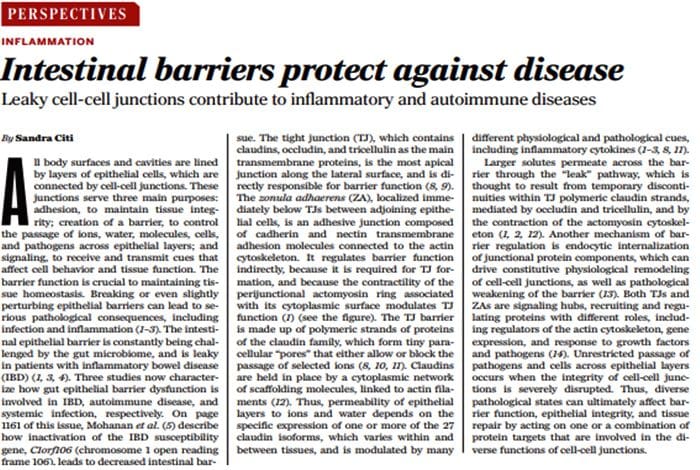

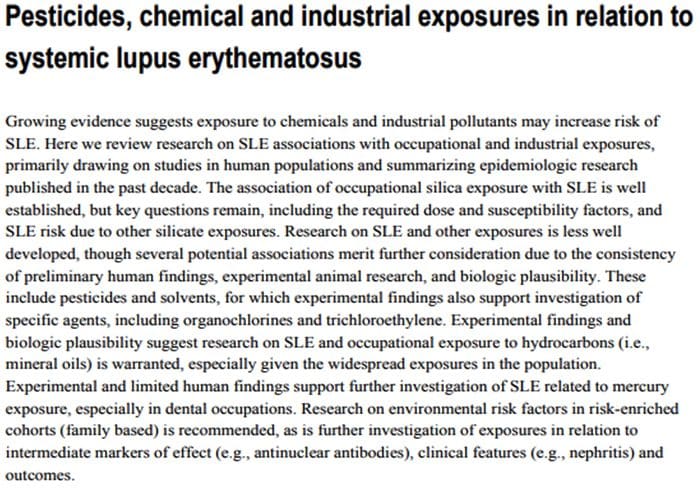

Exposome & The Alteration Of �Self� The Exposome Connections To Autoimmune Diseases Converting Self Into Non?Self

The Exposome Connections To Autoimmune Diseases Converting Self Into Non?Self

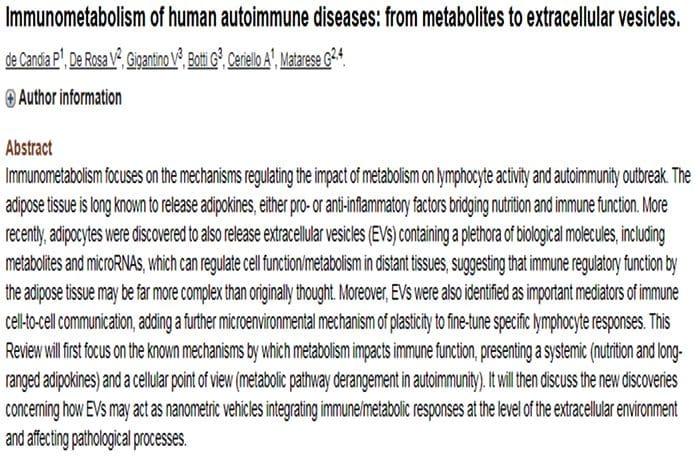

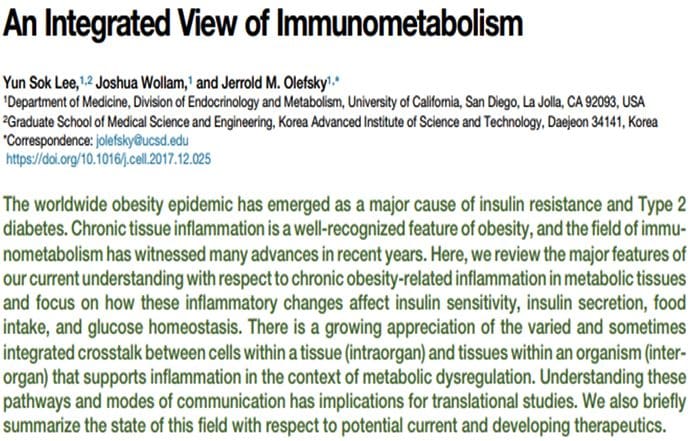

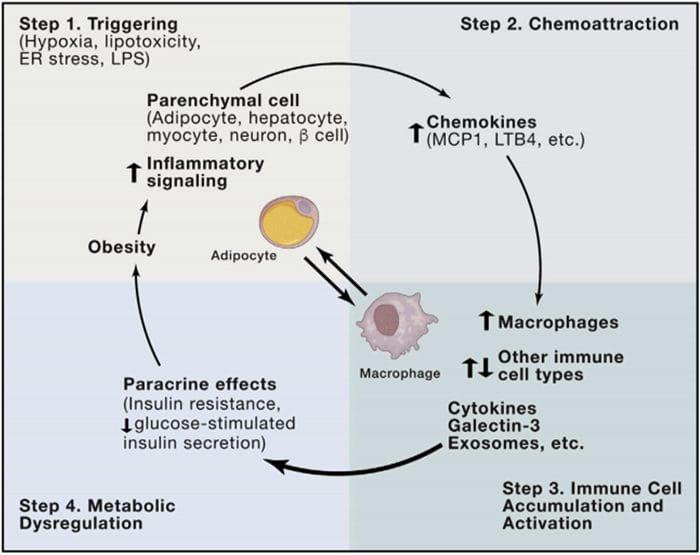

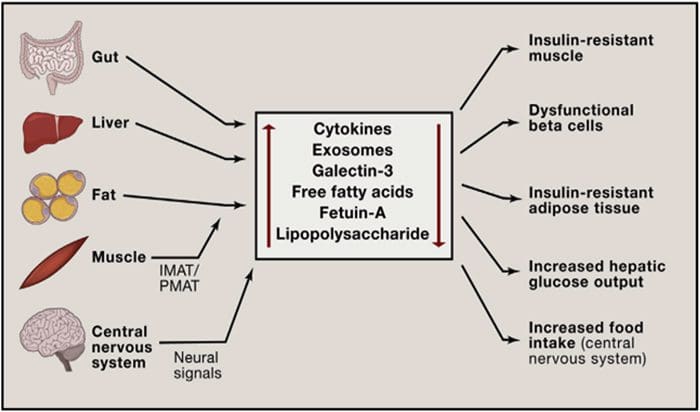

Multi?Organ Network Biology

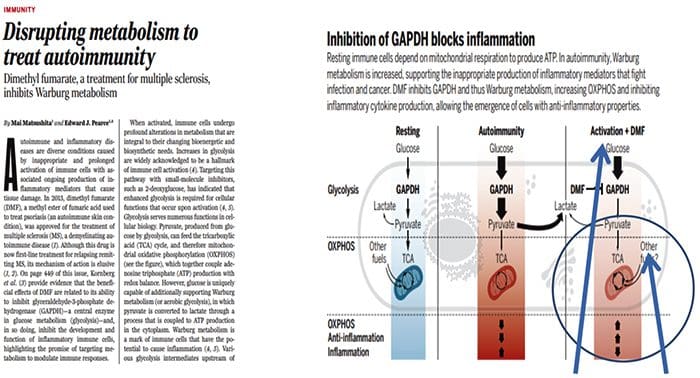

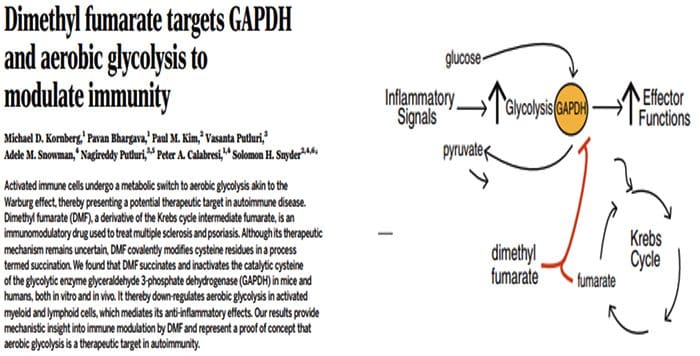

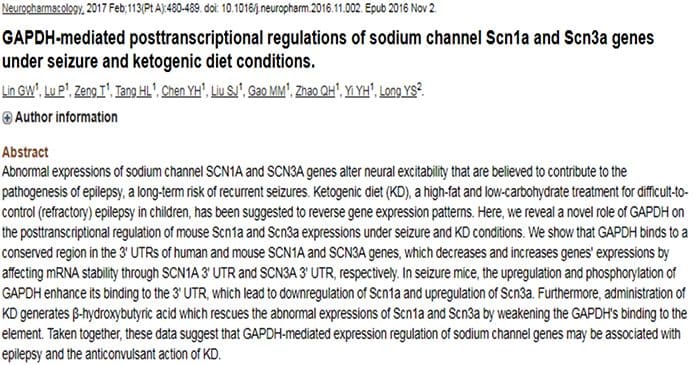

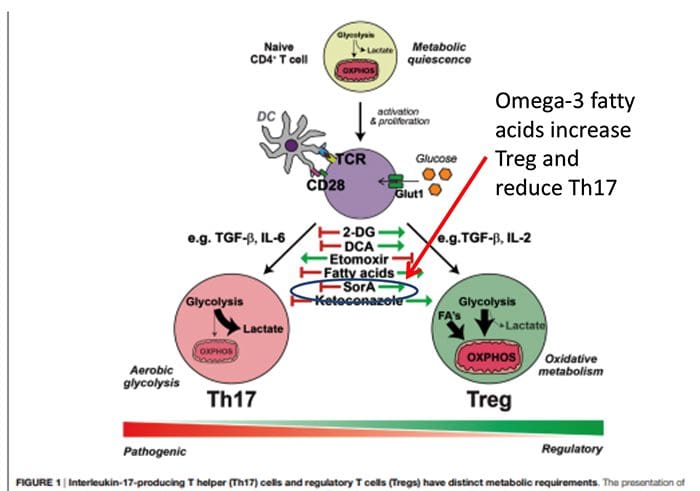

Multi?Organ Network Biology In Autoimmunity, Warburg Metabolism Is Increased Through Increased Activity Of GAPDH

In Autoimmunity, Warburg Metabolism Is Increased Through Increased Activity Of GAPDH

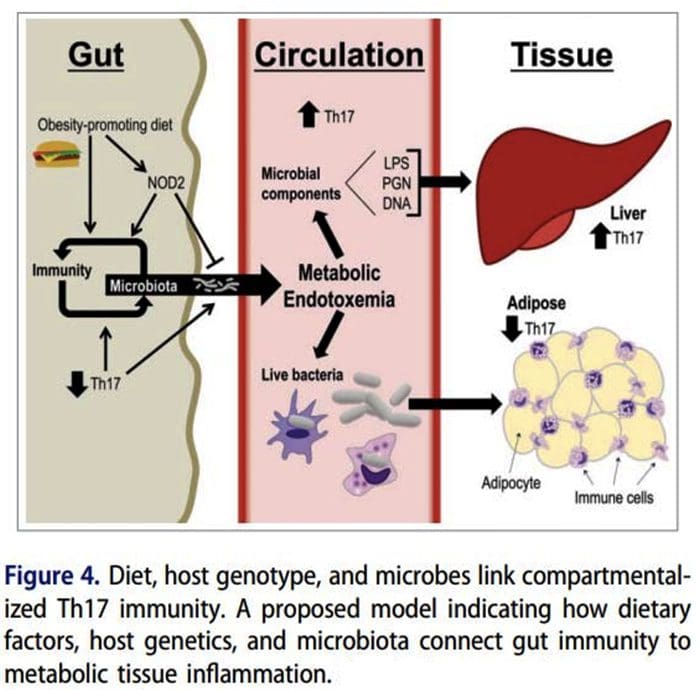

Origin Of IL?17 Producing Th17 Cells

Origin Of IL?17 Producing Th17 Cells What Is The Relationship Of The Gut Microbiome To Autoimmune Disease?

What Is The Relationship Of The Gut Microbiome To Autoimmune Disease?

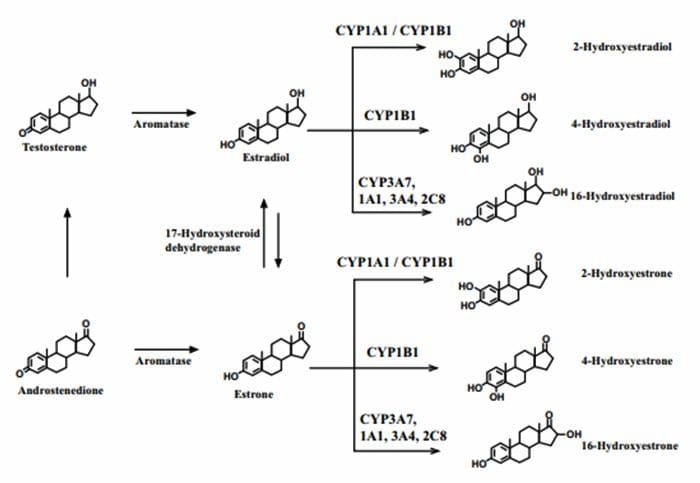

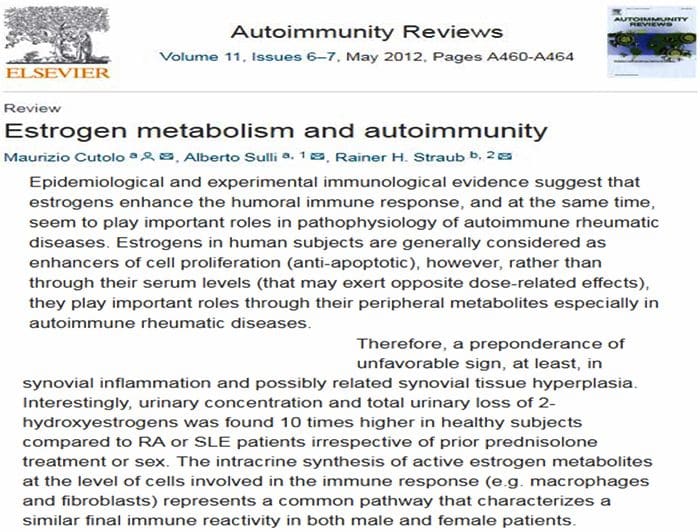

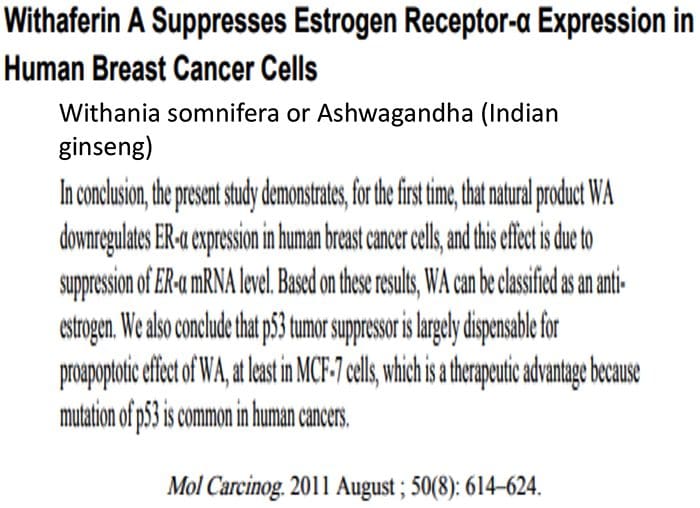

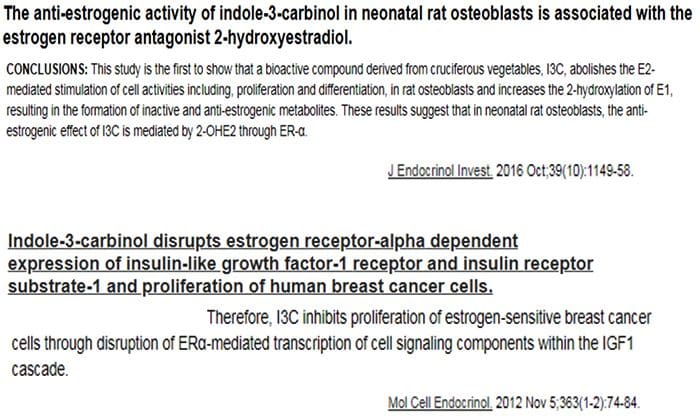

80% Of Patients With Autoimmune Disease Are Female

80% Of Patients With Autoimmune Disease Are Female

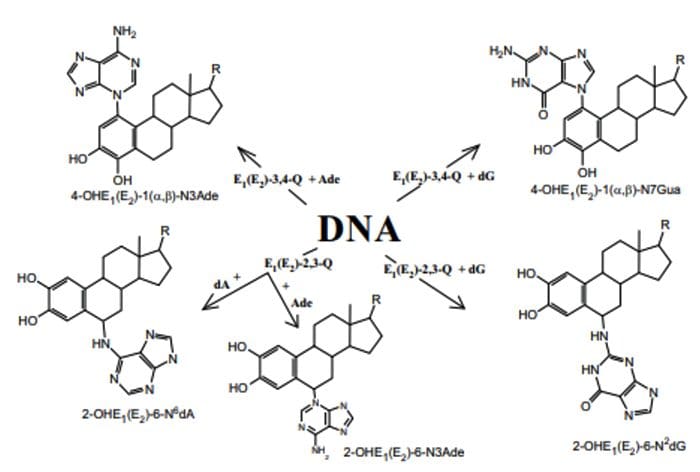

4?Hydroxyestrogens & DNA reactivity

4?Hydroxyestrogens & DNA reactivity

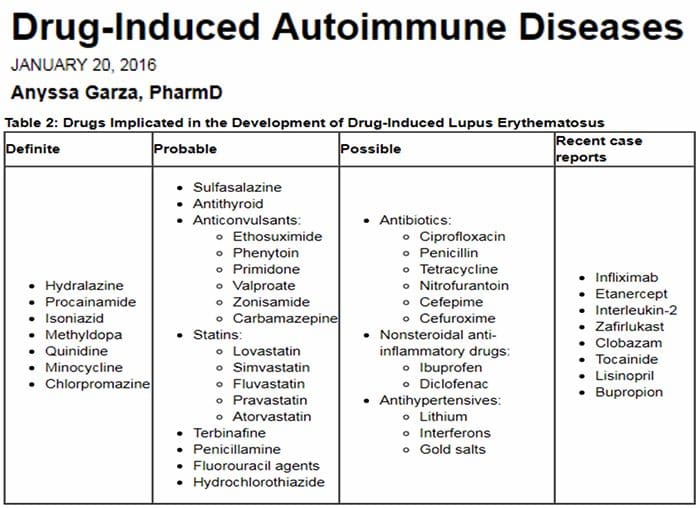

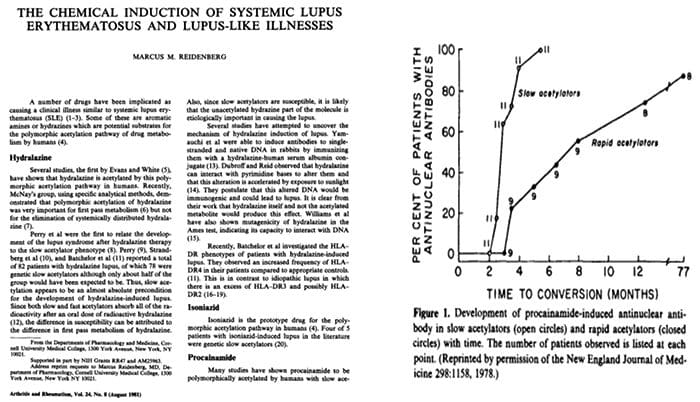

Relationship Of Hepatic Drug Detoxification To Anti?Nuclear Antibody Development

Relationship Of Hepatic Drug Detoxification To Anti?Nuclear Antibody Development

Endocrine Thyroid

Endocrine Thyroid Endocrine?Thyroid

Endocrine?Thyroid Musculoskeletal

Musculoskeletal Musculoskeletal & Kidney

Musculoskeletal & Kidney Neurological

Neurological Autoimmunity

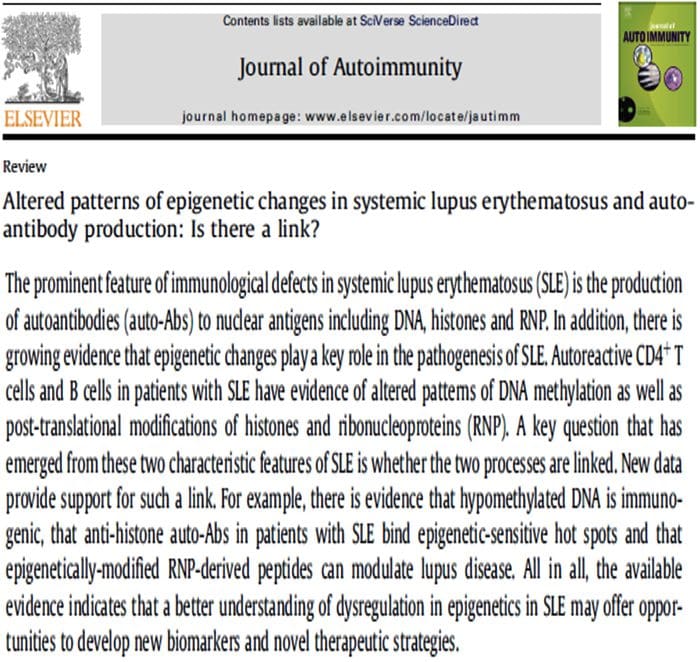

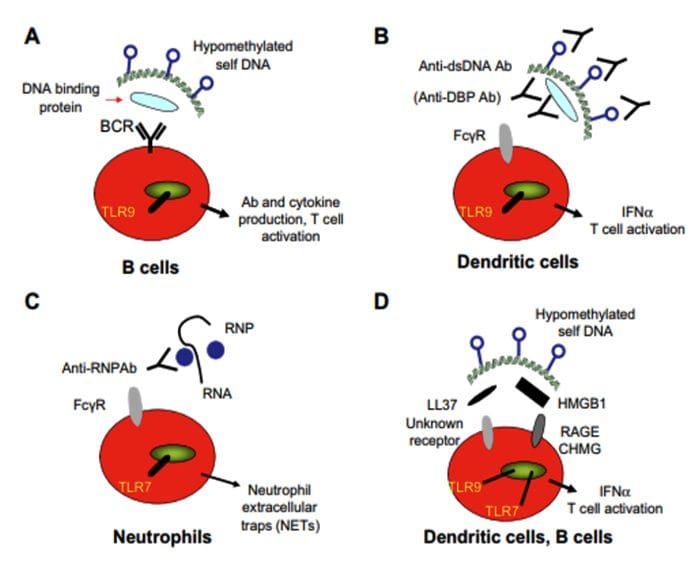

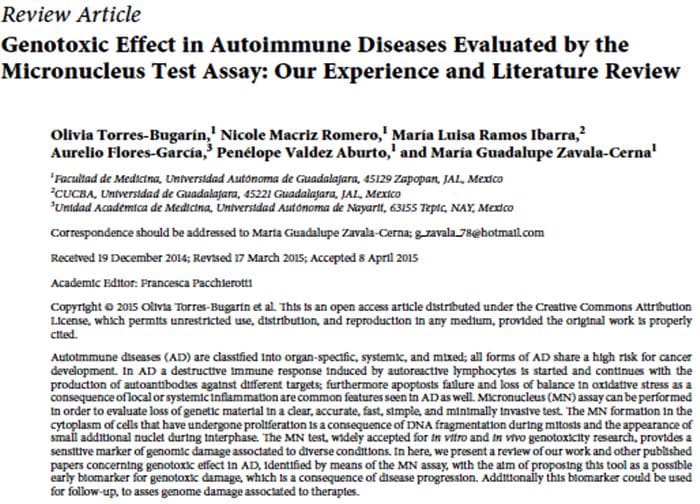

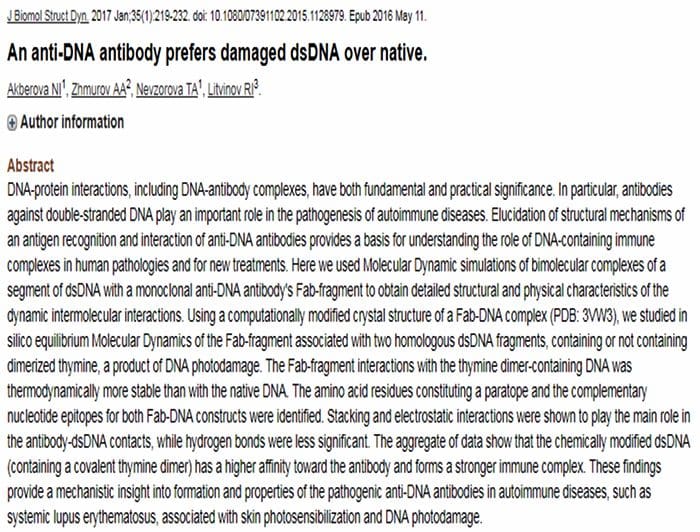

Autoimmunity Presence of Anti?Chromatin, DNA and RNA Antibodies

Presence of Anti?Chromatin, DNA and RNA Antibodies

What Biological Processes May Make Self Into Non?Self?

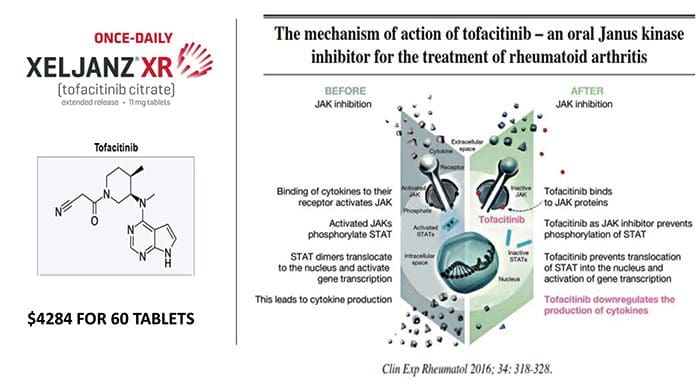

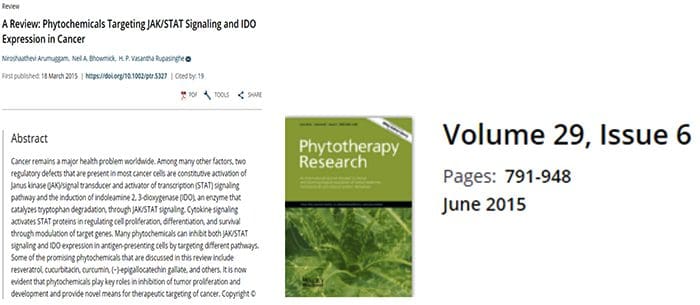

What Biological Processes May Make Self Into Non?Self? The Facts on Methotrexate For Rheumatoid Arthritis Treatment

The Facts on Methotrexate For Rheumatoid Arthritis Treatment

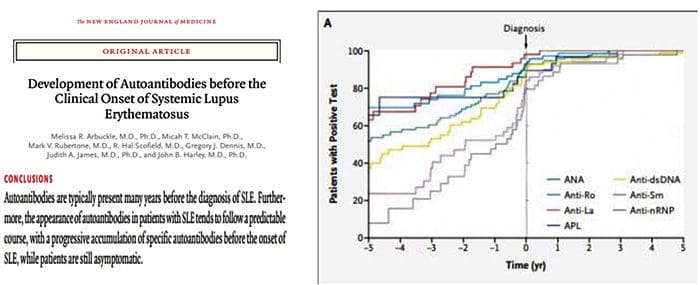

Autoantibodies Are Increasing At Least Five Years Before Diagnosis Of SLE

Autoantibodies Are Increasing At Least Five Years Before Diagnosis Of SLE

The Argument For Preventing Self From Becoming Non?Self

The Argument For Preventing Self From Becoming Non?Self