The Knee

The Knee | MRI may be requested for:

- Ligament injuries

- Meniscal tears and degeneration

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Osteochondral fractures

- Tendon disruptions

Bones & Cartilage Of The Knee

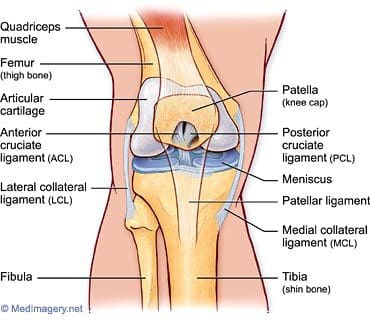

The knee joint is the largest, most complicated, and most vulnerable joint in the body, as it does not have a stable bony configuration. It consists of the tibiofemoral and patellofemoral articulations, which include the femur, tibia, and patella. The knee is a synovial joint that is enclosed by a ligament capsule. The capsule contains synovial fluid that keeps the joint lubricated (Figure 82). The knee provides flexible movement, but must also bear large weight and pressure loads. During walking, the knees support 1.5 times your body weight. When climbing stairs, they support 3-4 times your body weight. When squatting, your knees support 8 times your body weight.

Figure 82. Anatomy of the knee.

The tibiofemoral articulation is a modified hinge joint that allows bending and straightening, but also allows for slight rotation. This articulation consists of the lateral and medial condyles of the femur resting on the lateral and medial aspects of the tibial plateau. The femoral condyles make up the distal portion of the femur, which is expanded in order to assist with weight distribution at the knee joint. The medial femoral condyle is typically larger and rounder. The condyles are united anteriorly to provide the articular surface for the patella, but they are separated posteriorly by the intercondylar notch. This notch, or fossa, is the attachment site for the cruciate ligaments, the ligaments of Humphrey and Wrisberg, and the frenulum of the patellar fat pad. A large part of the posterior distal femur is called the popliteal surface. This area is covered by fat, which separates it from the popliteal artery. The medial and lateral edges of the popliteal surface are attachment sites for muscles. Superior to the femoral condyles are the epicondyles, which are the attachment sites for muscles, tendons, and capsular ligaments. The medial epicondyle is the attachment site for the medial (or tibial) collateral ligament (Figure 83). The lateral femoral epicondyle is the attachment site for the lateral (or fibular) collateral ligament, as well as the tendon of the popliteus muscle, fibers of the iliotibial tract, and the lateral capsular ligament. Superior and posterior to the epicondyles is the most distal extent of the linea aspera, the bony ridge of the femur.

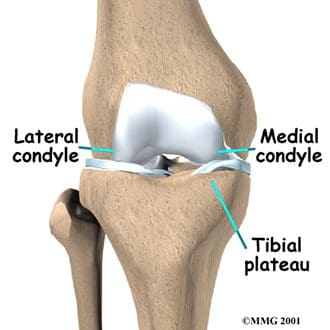

The tibia is the distal portion of the tibiofemoral articulation at the knee. The tibia is the second longest bone in the body, ranked just behind the femur. Its proximal end is flattened and expanded to provide a larger surface for the body weight that is transmitted through the femur. Like the femur, the proximal tibia has medial and lateral condyles. The medial condyle is larger, and somewhat flattened where it contacts the medial meniscus. The lateral condyle has a circular look to its femoral articular surface. The lateral tibial condyle articulates with the head of the fibula posteriorly, which is as close as the fibula comes to any involvement in the knee joint. Both the medial and lateral condyles rise in the center of the superior aspect of the tibia to form the intercondylar eminence. Posterior to this eminence are the attachments sites for the posterior horns of the medial and lateral menisci, which will be discussed with the ligaments of the knee. The medial and lateral tibial condyles, and the area of the intercondylar eminence are often grouped together and referred to as the tibial plateau (Figure 84). This is a critical weight-bearing area, and greatly affects the stability of the knee joint. The tibial tuberosity (or tubercle) is located on the anterior surface of the proximal tibial shaft. It has a smooth upper portion, and a roughened lower portion, which is the insertion site for the patellar tendon. The lateral side of the tibial tuberosity has a ridge for the attachment of fibers from the iliotibial tract. This is the strongest direct attachment site for the iliotibial tract. The IT tract, or band, helps in limiting lateral movement of the knee.

Figure 84. Tibial plateau.

Figure 83. Tibiofemoral anatomy.

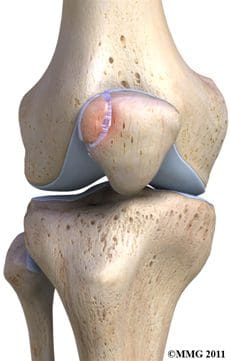

The patella is the third bone involved in the knee joint, specifically in the patellofemoral articulation. Patella means �little plate� in Latin, which describes the look and function of this sesamoid bone. The patella develops in the tendon of the quadriceps femoris muscle (Figure 85). It moves when the leg moves, and protects the knee joint by relieving friction between the bones and muscles when the knee is bent or straightened. The patellofemoral joint is a saddle-type synovial joint, allowing the patella to glide along the bottom front surface of the femur between the femoral condyles in the patellofemoral groove. Ossification of the patella is typically completed in females by age 10, and in males between the ages of 13-16. If the patella has more than one ossification center, and the additional center does not fuse, it is termed a bipartite patella (Figure 86).

Figure 86. Bipartite patella.

Figure 85. Patella location.

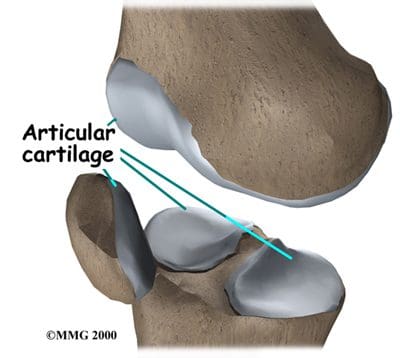

Articular, or hyaline, cartilage covers the ends of the bones involved in any joint. In the knee joint, this includes the distal end of the femur, the proximal end of the tibia, and the posterior aspect of the patella (Figure 87). In larger joints, this cartilage is approximately �� thick. Articular cartilage is white, shiny, rubbery, and slippery, enabling surfaces to slide against one another without damage. Articular cartilage is very flexible, due in part to its high water content, which also makes it highly visible on MRI. In contrast to the bones that it covers, articular cartilage has almost no blood vessels, so it is not good at repairing itself. Bones, on the other hand, have numerous blood vessels, and are good at self-repair.

Figure 87. Articular cartilage.

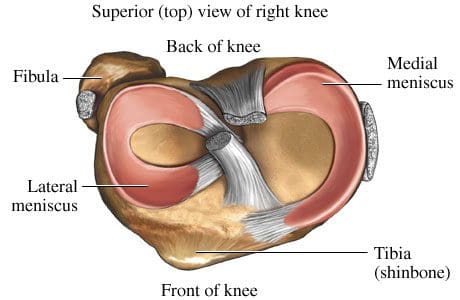

Another type of cartilage is found between the femur and tibia- the fibrous cartilage that makes up the medial and lateral menisci. The menisci, also referred to as �articular disks�, wrap around the round ends of the femur to fill the space between the femur and tibia (Figure 88). Since the menisci are more fibrous in composition, they have tensile strength and can resist pressure. They can help spread the force from our body weight over a larger area. By helping with weight distribution, the menisci protect the articular cartilage on the ends of the bones from excessive forces. The menisci are fashioned to be thicker on their outsides, creating a shallow socket on the tibial surface. They act like a wedge on the rounded distal portion of the femur, improving the overall stability of the knee joint by preventing any �rolling� of the femur. Despite how strong they sound, the menisci can crack or tear when the knee is forcefully rotated or bent. The medial meniscus is fused with the medial collateral ligament, so it is less mobile than the lateral meniscus. It is often injured when the anterior or posterior cruciate ligaments are injured. The inner 2/3 of the medial meniscus receives a limited blood supply, so the entire meniscus is usually slow to heal. The lateral meniscus suffers from fewer injuries than the medial meniscus. Meniscal tears are one of the most common causes of knee pain, with suspected meniscal tears the most common indication for an MRI of the knee joint.

Figure 88. Superior view of menisci of right knee.

Symptoms that might indicate a problem with the bones of the knee joint include locking of the joint, the knee giving way, crackling or grinding felt in the joint, and pain and swelling. Locking of the joint can be indicative of a �loose body� (bone, cartilage, or foreign object) in the joint space, which can often be removed through arthroscopy (Figure 89). A knee that gives way can indicate that the patella is out of the patellofemoral groove, which leaves the knee unstable. Crackling and grinding at the joint can result from degenerative arthritis or osteoarthritis, as well as from a dislocating patella. An increase in pain with activity can occur due to a stress fracture or bone fracture. One of the pathologic conditions that can affect the bones of the knee joint is osteochondritis dissecans, which can affect the distal femur, and was discussed previously with the femur anatomy. Various types of arthritis manifest in the bones of the knee joint, including osteoarthritis, infectious arthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis. Chondromalacia patella, also known as patellofemoral syndrome or �runner�s knee� results from an irritation of the undersurface of the patella (Figure 91). If the patella is not tracking correctly in the patellofemoral groove, the articular cartilage may rub against the knee joint (Figure 90). The cartilage degenerates, and becomes irritated and painful. This condition is most common amongst young, healthy athletes, especially females and runners that are flat-footed. Treatment is typically rest and physical therapy to stretch and strengthen the quads and hamstrings. If surgery is required, it may be to perform a �lateral release�, as the abnormal tracking of the patella can cause a tightening of the lateral tissues of the knee. The lateral release procedure cuts the tight tissues, so the patella can return to its normal position and tracking. Osgood-Schlatter disease involves the anteriorly located tibial tuberosity, and the patellar tendon that inserts on that tuberosity (Figures 92, 93). This condition affects children during their growth spurts, and is typically found more in boys. During growth spurts, contractions of the quad muscle put additional stress on the patellar tendon at its attachment site on the tibial tuberosity. This can result in multiple subacute avulsion fractures and inflammation of the tendon. Excess bone growth occurs on the tuberosity, and a lump on the tuberosity can be seen and felt. This lump can become irritated and swollen, causing knee and leg pain. This condition is typically worsened with running, jumping, and climbing stairs. Osgood-Schlatter usually resolves with rest, ice, compression and elevation, as well as maturity of the youngster�s skeleton.

Figure 89. Intraarticular loose body.

Figure 90. Patellofemoral groove.

Figure 91. Patellofemoral syndrome or �runner�s knee�.

Figure 92. Xray displaying Osgood-Schlatter disease.

Figure 93. MRI displaying Osgood- Schlatter disease.

Ligaments Of The Knee

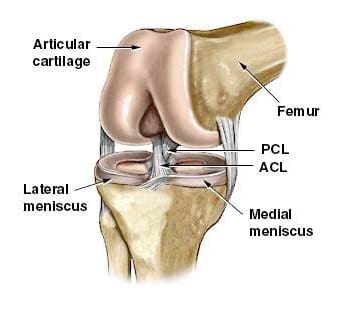

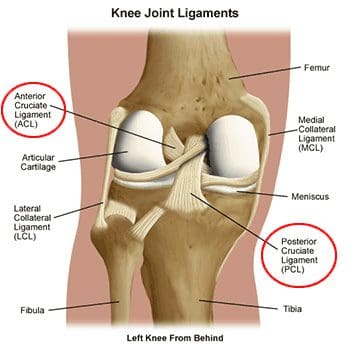

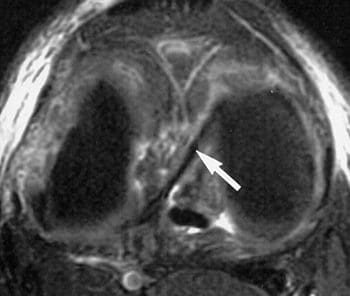

Ligaments are the tough bands of tissue that connect bones. They are considered to be �viscoelastic�, meaning they can gradually lengthen under tension, but return to their original shape when the tension is removed. However, if they are stretched for a prolonged period of time, or past a certain point, the ligaments cannot retain their original shape, and may eventually tear or snap. This is one of the reasons that a dislocated joint should be re-located as quickly as possible. If the ligaments lengthen, they leave the joint weakened and prone to future dislocations. Controlled stretching exercises to lengthen ligaments, and make the joints more supple, are part of the daily routines of athletes, gymnasts, dancers, etc. Damaged ligaments can lead to unstable joints, wearing of the cartilage, and eventually osteoarthritis. The numerous ligaments of the knee joint are the most important structures in controlling stability of the knee. Many of these ligaments were mentioned in the femur anatomy section, as they have attachments on the distal femur. The more important ligaments will be reviewed here in greater detail, in regards to their functions in the knee joint. The main intracapsular ligaments are the anterior and posterior cruciates (Figures 94, 95). Intracapsular ligaments are not very common in synovial joints. They provide stability, but permit a larger range of motion as compared to capsular or extracapsular ligaments. The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) stretches from the lateral femoral condyle to the anterior intercondylar area of the tibia, preventing the tibia from being pushed too far anterior relative to the femur. It is the more commonly injured of the cruciate ligaments, and can be torn during twisting and bending of the knee. Women are at higher risk for ACL ruptures due to the facts that the maximum diameter of the intercondylar fossa is in its posterior aspect (the ACL attaches anteriorly), and the overall width of the intercondylar fossa is smaller in females. The posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) stretches from the medial femoral condyle to the posterior intercondylar area of the tibia, preventing posterior displacement of the tibia relative to the femur. It is the stronger of the two cruciate ligaments, and is injured less frequently; however, it can be injured from direct force or trauma. The menisci are also considered to be intracapsular structures, with connections to ligaments inside and outside the joint capsule. Two of their intracapsular ligaments are the anterior and posterior transverse meniscomeniscal ligaments. They attach the medial and lateral menisci to each other at their anterior and posterior aspects. Posterior transverse meniscal ligaments are very rare- only 1-4% of knees will have them. Two additional intermeniscal ligaments are the medial and lateral oblique meniscomeniscal ligaments (Figure 96). Their names describe their anterior horn attachment sites; they attach on the posterior horn of the opposite meniscus (i.e. medial oblique meniscomeniscal attaches to the anterior horn of the medial meniscus and posterior horn of the lateral meniscus). The oblique meniscomeniscal ligaments both traverse the intercondylar notch, and pass between the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments (Figure 97).

Figure 94. Cruciate ligaments and menisci.

Figure 95. Posterior view of cruciate ligaments of left knee.

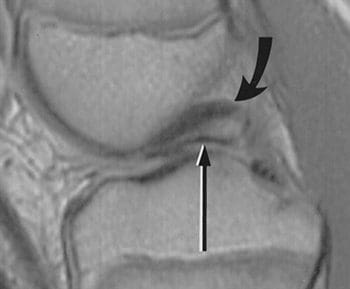

Figure 96. Axial fatsat T2 FSE image with arrow indicating

oblique meniscal ligament coursing from anterior horn of

medial meniscus to posterior horn of lateral meniscus.

Figure 97. Sagittal dual-echo T2 through the intercondylar notch at the level of the posterior cruciate ligament (curved arrow); thin linear structure of low signal intensity inferior to PCL represents the oblique meniscomeniscal ligament (straight arrow); sometimes misinterpreted as displaced meniscal fragment.

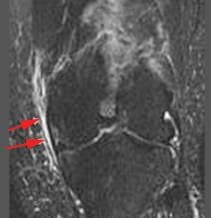

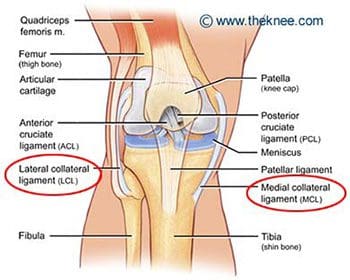

The medial (or tibial) collateral ligament is considered a capsular ligament, as it is part of the articular capsule surrounding the synovial knee joint. It acts as mechanical reinforcement for the joint, protecting the knee from valgus force, or being bent open medially due to stress on the lateral side of the knee. The medial collateral ligament (MCL) is one of the most commonly injured of all knee ligaments, occurring in all sports, in all ages, and often times with medial meniscal tears (Figures 98-101). It has both superficial and deep components. Fibers from the superficial portion of the MCL attach to the medial epicondyle of the femur and the medial tibial condyle. Fibers from the deep medial collateral ligament attach to the medial meniscus. Proximal to the attachment point, this ligament is referred to as the meniscofemoral ligament, as it attaches the medial meniscus to the medial aspect of the femur. Distal to the meniscal attachment, the ligament is referred to as the meniscotibial (or coronary) ligament, as it attaches the medial meniscus to the medial aspect of the tibia. The meniscofemoral and meniscotibial are also referred to as the meniscocapsular or medial capsular ligaments, as they play an important role in anchoring peripheral parts of the medial meniscus in the medial side of the knee. The meniscotibial ligament is typically injured more often than the meniscofemoral ligament. The meniscotibial ligament attaches to the tibia several millimeters inferior to the articular cartilage. Its job is to stabilize and maintain the meniscus in its proper position on the tibial plateau. Disruption of the meniscotibial ligament can result in a floating meniscus or meniscal avulsion, while the meniscofemoral ligament may not be affected. The deep medial collateral ligament is short, and tightens quickly with rotation motions. It is often damaged, along with the ACL, when the mechanism of injury involves tibial rotation. Diagnosis and surgical repair of the deep medial collateral ligament can be challenging.

Figure 98. Normal MCL is linear,

has low signal intensity.

Figure 99. Grade 1 sprain shows adjacent edema, no change in signal intensity of MCL.

Figure 100. Grade 2 sprain or partial tear shows increased edema,

abnormal signal intensity,

thickening or thinning of ligament.

Figure 101. Grade 3 involves complete disruption of ligaments or attachments.

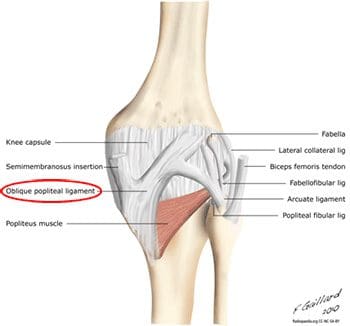

In addition to fibers of the medial collateral ligament, the deep portion of the capsular compartment of the medial knee is the location of the medial knee�s posterior support. The posterior oblique ligament is attached proximally to the medially located adductor tubercle of the femur, and distally to the tibia and the posterior aspect of the knee joint capsule. If the posterior oblique is injured, it is usually torn from its femoral origin. The posterior oblique ligament provides static resistance to valgus loads as the knee moves into full extension, as well as dynamic stabilization to valgus forces (stress from lateral side) as the knee moves into flexion. It acts as an important restraint to posterior tibial translation in cases of posterior cruciate ligament injury. The posterior oblique ligament has three �arms�. Its superior capsular �arm� becomes continuous with the posterior knee capsule, and the proximal portion of the oblique popliteal ligament. The oblique popliteal ligament is also an important posterior stabilizing structure for the knee joint Figure 102). It extends from the posteromedial aspect of the tibia, running obliquely and laterally upward to insert near the lateral epicondyle of the femur.

Figure 102. Oblique popliteal ligament in posterior view of knee.

Figure 103. Medial (tibial) and lateral (fibular) collateral ligaments.

The lateral (or fibular) collateral ligament is considered an extracapsular ligament. It helps to provide joint stability and protects the lateral side of the knee from varus forces, or inside bending forces that are directed at the medial side of the knee. Injuries to the lateral collateral ligament are less common than injuries to the medial collateral, as the opposite leg can guard against medial forces that can lead to lateral collateral injuries. Injuries can occur in sports such as soccer and rugby, where the knee is extended and unprotected during running. The lateral, or fibular, collateral ligament stretches obliquely downward and backward, from the lateral epicondyle of the femur to the head of the fibula (Figure 103). It is not fused with the capsular ligament or with the lateral meniscus, so it has increased flexibility and decreased incidence of injury when compared to the medial collateral ligament. Similar to the medial meniscus, the lateral meniscus has a meniscotibial, or coronary, ligament. It connects the inferior edges of the lateral meniscus to the periphery of the tibial plateau. The lateral meniscus also has a meniscofemoral ligament that extends from the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus to the lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle. It is given two distinct names, based on its location in relation to the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL). The ligament of Humphrey passes in front of the posterior cruciate ligament. It is less than 1/3 the diameter of the posterior cruciate ligament, but may be confused for the posterior cruciate during arthroscopy. The ligament of Wrisberg passes behind the posterior cruciate ligament, and is about � of the posterior cruciate�s diameter (Figure 104). Its femoral origin often merges with the posterior cruciate ligament. Both ligaments are present in only about 6% of knees. Approximately 70% of people have one or the other of these ligaments, with the majority possessing the more posterior ligament of Wrisberg (Figure 105). MRI is the preferred imaging modality for medial collateral or lateral collateral ligament injuries, as it can detect any associated internal knee derangements, cruciate-collateral ligament injuries, or cartilage deficiencies.

Figure 104. Rendering of posterior knee, arrow indicates Ligament of Wrisberg; courses obliquely from lateral aspect of medial femoral condyle to posterior horn of lateral meniscus,

remains posterior to PCL.

Figure 105. Arrow indicates �Wrisberg pseudo-tear�; intermediate signal

intensity line at junction of

Ligament of Wrisberg and normal posterior horn of lateral meniscus; often mistaken for a meniscal tear.

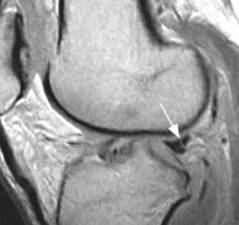

The patellar ligament is the connection between the patella and the tibia, extending from the apex (inferior aspect) of the patella to the tibial tuberosity. Technically, it is connecting two bones, so it is a ligament. However, it is most often referred to as the patellar tendon, because the superficial fibers that cover the front of the patella and extend to the tibia are continuous with the central portion of the common tendon of the quadriceps femoris muscle. The posterior surface of the patellar ligament is separated from the synovial membrane of the knee joint by a large infrapatellar pad of fat. Injuries to the patellar ligament can occur from overuse, such as sports that involve jumping and quick directional changes, as well as running-related sports. This is the ligament that is injured in jumper�s knee (or patellar tendonitis), which begins with inflammation, and can lead to degeneration or rupture of the patellar ligament and the tissue around it (Figure 106). Patients with patellar ligament injuries typically complain of pain in the area below the kneecap, which will increase with walking, running, squatting, etc. They can often be treated in the same manner as other soft tissue injuries- with rest, ice, compression and elevation. The patellar ligament attachment at the tibial tuberosity is the site of Osgood-Schlatter disease, which was discussed previously.

Figure 106. Patellar tendonitis (jumper�s knee).

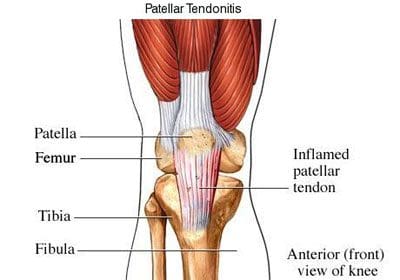

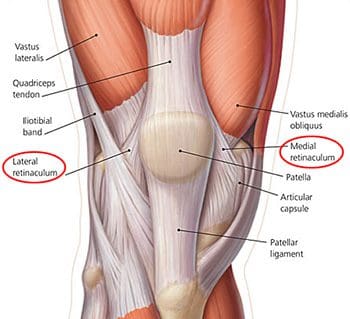

Along the sides of the patella and the patellar ligament are the medial and lateral patellar retinacula (Figure 107). They are fibrous tissue stabilizers for the patella that form from the medial and lateral portions of the quad tendons as they pass down to insert on either side of the tibial tuberosity. The lateral retinaculum is the thicker of the two, but both have superficial and deep layers. Within the deep layers are various ligaments (whose names indicate the structures they connect) that help support the patella in its position, relative to the femur below it. The deep layer of the lateral patellar retinaculum is the location where the lateral patellofemoral ligament meets the iliopatellar band, which is a tract of fibers from the iliotibial (IT) band that connects to the patella. The deep layer of the medial patellar retinaculum has three focal capsular thickenings, referred to as the medial patellofemoral, medial patellomeniscal, and medial patellotibial ligaments. The medial patellofemoral ligament is strong enough to influence patellar tracking, and acts as a major medial restraint. Imbalances in the forces that control patellar tracking during flexion and extension of the knee can lead to patellofemoral pain syndrome (runner�s knee), one of the most common causes of knee pain. This can result from overuse, trauma, muscle dysfunction, patellar hypermobility, and poor quadriceps flexibility. Typical symptoms include pain behind or around the patella that is increased with running, and activities that involve knee flexion. MRI is typically not necessary for this diagnosis. Physical therapy has been found to be effective for the treatment of patellofemoral pain syndrome.

Figure 107. Lateral and medial retinaculum.

Muscles & Tendons Of The Knee

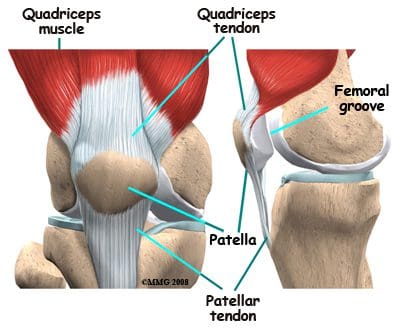

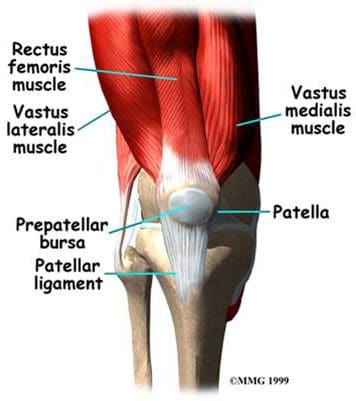

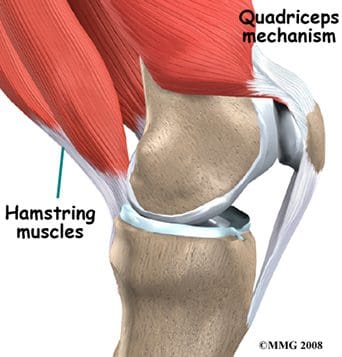

The flexor and extensor muscles of the knee have been discussed previously, as the majority of them are the anterior and posterior muscles of the thigh. We will review the thigh muscles involved in knee movement, and add two muscles of the lower leg that also affect the knee. The quadriceps femoris muscles of the anterior thigh are the main knee extensors (Figure 108). As these muscles contract, the knee joint straightens. The tendons of the vastus medialis, vastus intermedius, vastus lateralis, and rectus femoris join at the superior aspect (base) of the patella to form the patellar tendon. This tendon continues over the patella and attaches it to the tibial tuberosity (since it is connecting bone to bone, it is sometimes called the patellar ligament). The quadriceps, along with the gluteal muscles, are responsible for the thrusting forces necessary for walking, running, and jumping. The quads also help control movement of the patella, as they are attached to it by the quadriceps tendons (Figure 109). The patella increases the force exerted by the quadriceps muscles as the knee is straightened.

Figure 108. Anterior thigh muscles – knee extensors.

Figure 109. Quadriceps controlling the patella.

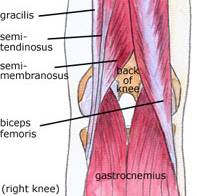

The posterior thigh muscles, also known as the hamstrings, are the main knee flexors, with assistance from the sartorius, gracilis, gastrocnemius, and popliteus muscles. The knee bends when the hamstrings contract. The hamstring muscles give the knee joint the strength needed for propulsion in running and jumping. They also help to stabilize the knee by protecting the collateral and cruciate ligaments, especially when the knee twists. The three hamstring muscles have varying attachment sites around the knee joint (Figure 110). The biceps femoris attaches to the head of the fibula and the superolateral aspect of the tibia. The semitendinosus attaches on the anterior aspect of the tibia, medial to the tibial tuberosity, crossing over the medial collateral ligament. The tendon of the semitendinosus muscle is sometimes used for cruciate ligament reconstruction. The semimembranosus attaches at the posteriomedial aspect of the medial tibial condyle. The sartorius muscle is also a knee flexor, although it is an anterior thigh muscle. It inserts on the anterior medical aspect of the tibia. The gracilis muscle of the medial thigh is one of the hip adductors, but also plays a part in knee flexion. Like the semitendinosus tendon, the tendon of the gracilis is sometimes used for cruciate ligament reconstructions. The gracilis attaches to the medial aspect of the proximal tibia.

Figure 110. Posterior knee

muscles – knee flexors.

Additional flexors of the knee joint include some of the posterior muscles of the lower leg. The large superficial gastrocnemius muscle has a medial and a lateral head, which originate from the medial and lateral femoral condyles, respectively. It runs the length of the posterior lower leg, attaching to the calcaneus by the Achilles tendon. The gastrocnemius gives us the ability to flex our knee while our foot is flexed, as it connects to both joints. It is involved in standing, walking, running, and jumping. The popliteus is a deep posterior lower leg muscle that helps with knee flexion, and also rotates the tibia medially, which aids in knee stability. The popliteus originates from the outer margin of the lateral meniscus of the knee joint. It extends posteriorly and inserts on the medial aspect of the tibia, inferior to the medial tibial epicondyle.

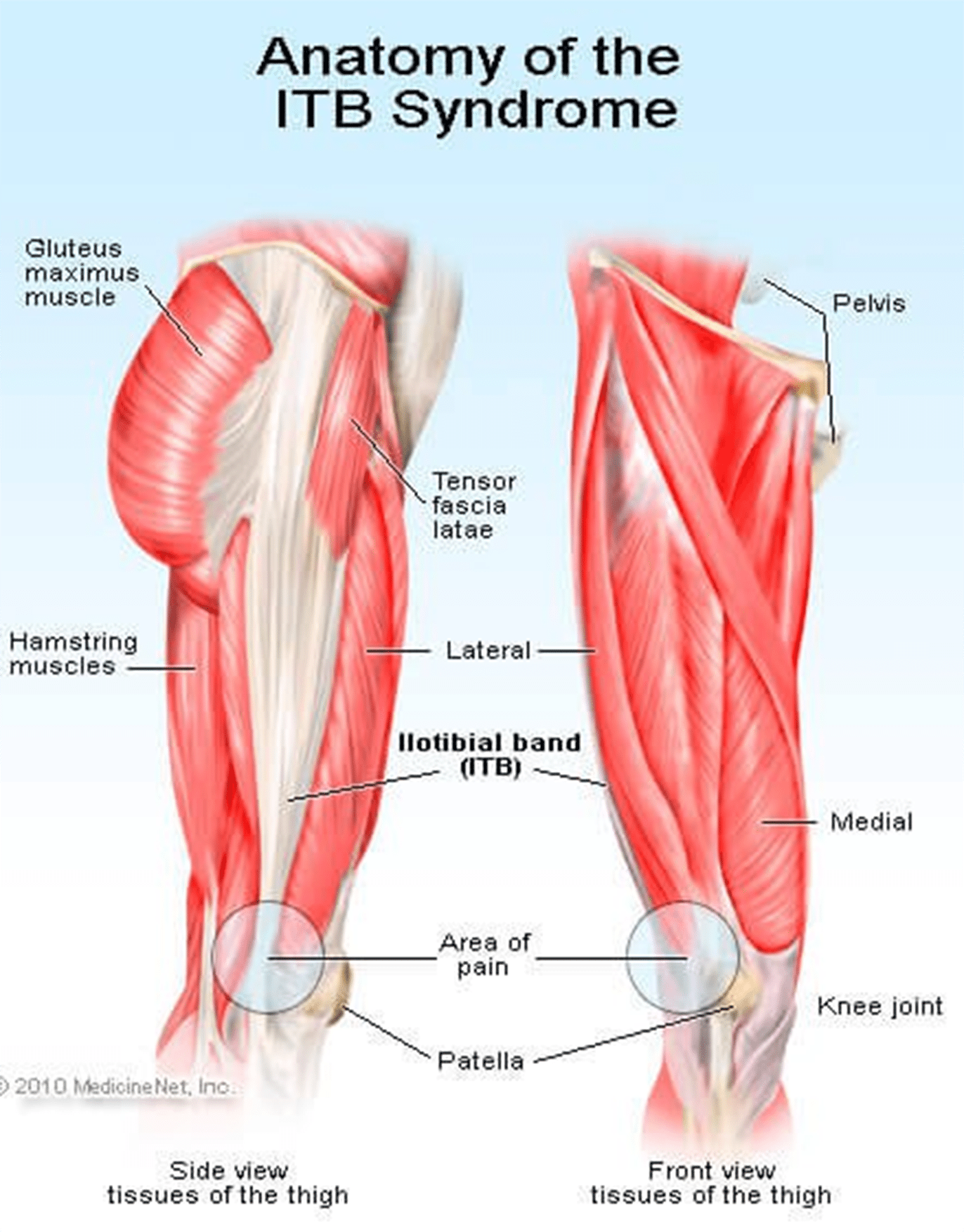

The important tendons of the knee include the quadriceps, patellar, and hamstring tendons, and the iliotibial band (Figure 111). Tendons attach muscles to bones. These major knee tendons have all been discussed with either the bones or the muscles that they attach. The quadriceps tendon was mentioned with the quadriceps muscle as the muscle�s attachment to the patella. The quad tendon continues over the patella, then attaches the apex of the patella to the tibial tuberosity. It is then called the patellar tendon (or ligament). Hamstring tendons were discussed with the hamstring muscles, the posterior muscles that are flexors of the knee. Hamstring tendons are sometimes used for cruciate ligament reconstructions. Tendonitis, which is the inflammation of a tendon, is a common knee injury amongst athletes in a variety of sports. The iliotibial band (or IT tract) functions like a tendon, as it attaches the knee to the tensor fasciae latte muscle. The band is actually a fibrous reinforcement of the fascia lata, or deep tissue of the thigh. It runs from the ilium to the tibia. Proximally, it acts as a hip abductor, while distally it acts as lateral stabilization for the knee, and aids with medial rotation of the tibia. The IT band is in constant use during walking and running, which can lead to irritation at the point where it passes over the lateral femoral epicondyle. A �tight� IT band can cause inflammation and/or irritation at the femoral epicondyle, or at the point of insertion on the lateral tibial condyle. This condition is called IT band friction syndrome. It is common amongst runners, hikers, and cycling enthusiasts.

Figure 111. Tendons of the knee.

Nerves Of The Knee

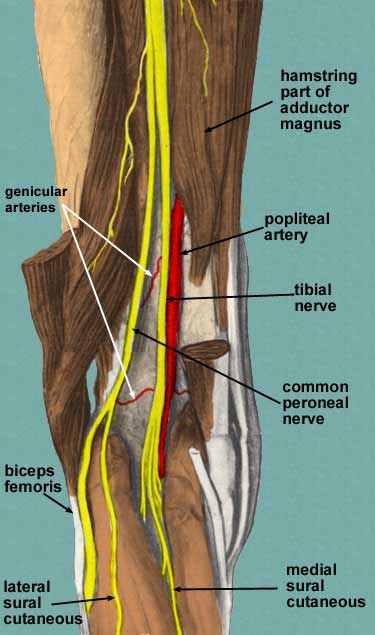

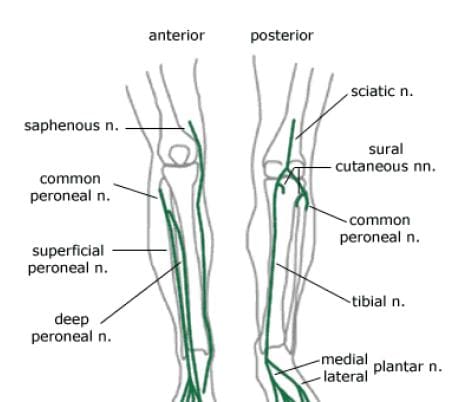

The main nerves to the knee that come from the sacral plexus of nerves are the tibial nerve and the common peroneal nerve (Figure 112). Both are branches of the sciatic nerve, and begin posteriorly, slightly above the actual knee joint. Both of these nerves, or their branches, continue through the lower leg and foot, providing sensation and muscle control. The tibial and common peroneal nerves are also both involved in cutaneous innervation, which is the supply of nerves to the skin of the knee. The tibial nerve remains posterior and more medial, branching at the medial ankle to innervate the foot. The common peroneal nerve begins posterolaterally, moving anteriorly near the neck of the fibula. It then branches into the superficial and deep peroneal nerves, which continue their anterior descent to the foot. The tibial and common peroneal nerves are the most commonly injured nerves when a knee is dislocated. Nerves can grow back, but they do so at a rate of approximately � inch per month.

Figure 112. Sacral plexus nerves of knee.

Nerves from the lumbar plexus that affect the knee include the lateral femoral cutaneous, and the saphenous, which is a branch of the femoral nerve (Figure 113). The saphenous nerve travels more medially and gives off infrapatellar branches around the knee joint. Below the knee, the saphenous nerve sends branches to the skin of the anterior and medial lower leg. The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve sends an anterior branch to the skin of the anterior and lateral thigh, down to the area of the knee. Terminal filaments of this nerve communicate with the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve, forming the peripatellar plexus.

Figure 113. Lumbar plexus nerves of knee.

Arteries & Veins Of The Knee

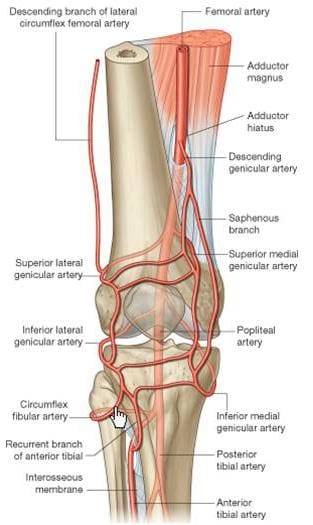

The popliteal artery, a branch of the superficial femoral artery, is the main arterial supply to the knee joint. It runs along the posterior aspect of the distal femur, behind the knee joint. At the supracondylar ridge, the popliteal artery gives off the blood supply to the knee, which consists of various genicular arteries (Figure 114). Inferior to the knee joint, the popliteal branches into the anterior and posterior tibial arteries, which supply the lower leg. The popliteal artery is a common site for both atherosclerosis and aneurysms, and is listed as the most common site for peripheral arterial aneurysms. Approximately 50% of these aneurysms are bilateral. Although they rarely rupture, popliteal aneurysms may serve as a focus for abrupt thrombotic occlusion of the involved popliteal artery, which can affect the foot on the same side. A thrombus within an aneurysm can also lead to a distal embolism. The genicular arteries are sources of continued blood flow to the knee and lower limb, in case of an obstructed popliteal artery. The descending genicular, also called the highest or supreme genicular, branches from the femoral artery, just superior to the popliteal branch. It supplies the adductor magnus and hamstring muscles, then joins with the network of genicular arteries around the knee joint. The middle genicular pierces the oblique popliteal ligament, and supplies the ligaments and synovial membrane inside the knee articulation (including the ACL and PCL). The sural artery joins the anastomoses of the genicular arteries, and also supplies muscles of the lower leg, including the large gastrocnemius muscle. The anastomotic pattern around the knee joint is supplied by the popliteal artery posteriorly, the descending genicular artery medially, and the descending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery laterally. The genicular arteries involved in the anastomosis are labeled as the medial and lateral superior geniculars, and the medial and lateral inferior geniculars.

Figure 114. Arteries of knee.

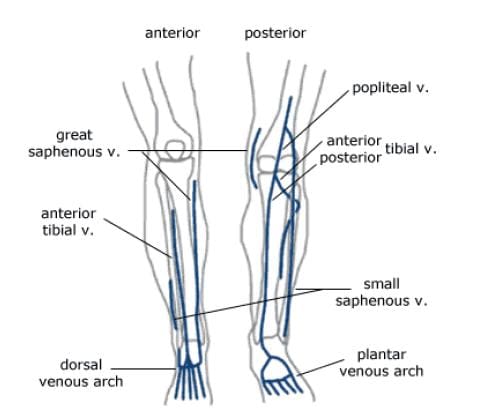

The major deep veins around the knee joint are the popliteal vein, and the anterior and posterior tibial veins (Figure 115). The popliteal vein begins at the junction of the tibial veins in the posterior aspect of the lower leg, just inferior to the knee joint. It ascends posteriorly, continuing as the femoral vein about halfway up the thigh. As deep veins typically follow the arteries, the genicular veins accompany the genicular arteries around the knee joint, then drain into the popliteal vein. The important superficial veins around the knee joint are the small and great saphenous veins. Superficial veins typically do not follow arteries, but rather travel with cutaneous nerves. The small saphenous ascends the lower leg posteriorly, angling from lateral to medial. It merges with the popliteal vein at a position slightly superior to the knee joint. The great saphenous vein, the longest vein in the body, has a medial and anterior course in the lower leg. It moves to a posterior position, but stays medial along the knee joint, moving alongside the medial epicondyle of the femur. The great saphenous then moves anteriorly again through the thigh.

Figure 115. Veins of knee.

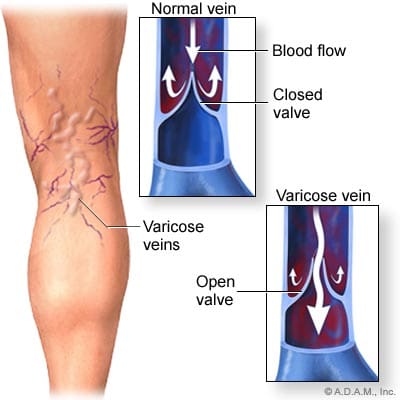

Varicose and �spider� veins are often seen in the leg in the posterior aspect of the knee joint. As mentioned previously, in the femoral vein discussion, veins have valves to ensure the �one-way� uphill flow of blood back to the heart (Figure 116). Communicating vessels, also called perforating veins, exist between the deep and superficial veins to help compensate for valves that may be incompetent, and are allowing blood reflux. If venous walls are weakened or dilated, the cusps of the valves can no longer close properly, and the valves can become incompetent. This leads to an increase in the weight of the column of blood for the veins that are �downstream� from the bad valve. Blood can pool in these veins, causing them to become varicose, where the veins swell, become tortuous, and even bulge through the skin surface. Reticular veins, which are smaller varicose veins that do not bulge through the skin, as well as very small �spider� veins are both typically less severe conditions, but both still involve the backwards flow of blood. Removal of severe varicose veins will actually help blood flow, as the blood will no longer be stagnant in the pooled areas.

Figure 116. Varicose veins around knee.

Bursae Of The Knee

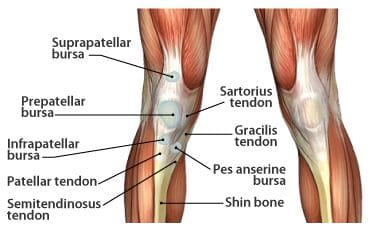

The synovial knee joint is home to a large number of bursae (Figure 117). These are fluid sacs and synovial pockets that surround and sometimes communicate with the joint cavity. They facilitate friction-free movement between the bones and moving structures (tendon, muscle). Fluid or debris can collect in the bursa, or fluid can extend into the bursa from the adjacent joint in situations such as excessive friction, infection or direct trauma. This type of pathological enlargement of the bursa is referred to as bursitis, which can mimic several peripheral joint and muscle abnormalities. Radiologists must be able to accurately identify bursal pathology, especially amongst the numerous knee bursae (14 reported in some literature). We will identify a few of the more common bursa, beginning with the suprapatellar bursa. This bursa lies between a quadriceps tendon and the femur, superior to the patella (Figure 118). Fluid is commonly found here when patients have a joint effusion. Bursitis of the prepatellar bursa is also known as �housemaid�s knee�. It occurs from repetitive trauma from kneeling, as seen with housemaids, wrestlers, and carpet-layers. This bursa is found between the patella and the skin (Figure 119). Inflammation of the superficial infrapatellar bursa may be called �Clergyman�s knee�, another bursitis that can occur from excessive kneeling. This bursa is located between the distal third of the patellar tendon and the overlying skin (Figure 120).

Figure 117. Bursae in the knee.

Figure 118. T2 gradient

displaying suprapatellar

bursa.

Figure 119. T2

fatsat displaying

prepatellar bursa.

Figure 120. T2 fatsat

displaying infrapatellar

bursa.

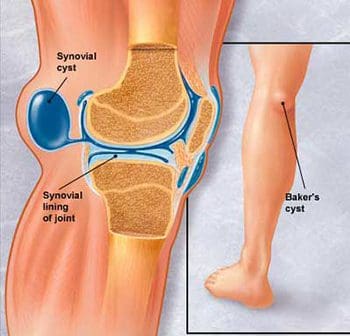

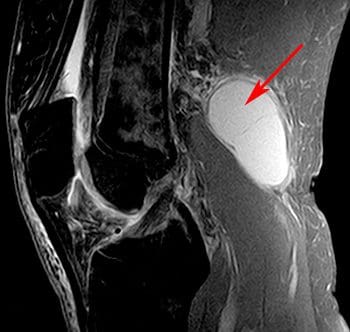

The synovial sac of the knee joint sometimes forms a posterior bulge, known as a Baker�s cyst or popliteal cyst (Figure 121). It typically forms between the tendons of the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle and the semimembranosus muscle, posterior to the medial femoral condyle. Baker�s cysts are not true cysts, as they typically maintain open communication with the synovial sac. However, they can pinch off, and they can rupture. They are usually asymptomatic, but can be indicative of another problem of the knee, such as arthritis or a meniscal tear. Aspiration of the synovial fluid can be performed if the cyst becomes problematic. Treatment is usually necessary if a Baker�s cyst ruptures, as it can cause acute pain behind the knee, and swelling of the calf muscles. A ruptured cyst can also mimic a DVT or thrombophlebitis. Ultrasound and MRI can both be used for confirmation of a Baker�s cyst (Figure 122).

Figure 121. Lateral view of Baker�s cyst.

Figure 122. Sagittal image of Baker�s cyst on MRI.

Scan Setups

The following are HMSA suggestions for knee imaging. Knee protocols should be designed to yield diagnostic images of the menisci, bones, articular cartilage, and all ligamentous structures of the knee. While many radiologists may require additional imaging of the ACL, protocols that are designed for optimal imaging of the cartilage and menisci should also produce adequate images of the ACL. Always check with your radiologist for his/her imaging preferences.

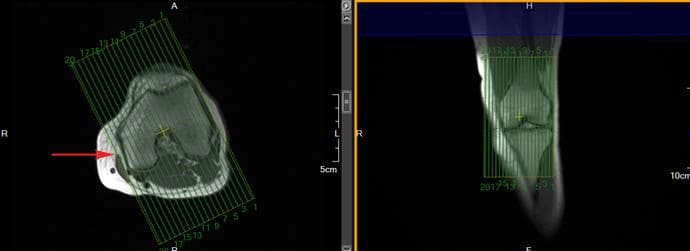

Axial Scans

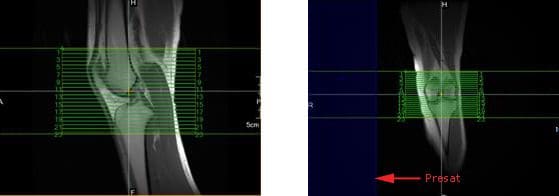

When positioning axial slices for the knee, sagittal and coronal images can be used to insure inclusion of all pertinent anatomy. The slices should extend superiorly to include the entire patella, and inferiorly to include the tibial tuberosity and patellar tendon insertion. A presat can be placed over the unaffected lower extremity to reduce the possibility of wrap-around artifact, as seen in the coronal image in Figure 139.

Figure 139. Axial slice setup using sagittal and coronal images.

Coronal Scans

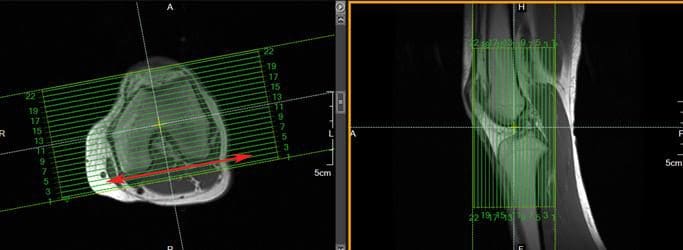

Coronal slices of the knee should include the anatomy from the posterior femoral condyles to the anterior portion of the patella. Visualize a line connecting the lateral and medial condyles of the femur. Typically, the coronal slices are angled so that they are parallel to that line, as seen in the axial image in Figure 140.

Figure 140. Coronal slice setup using axial and sagittal images.

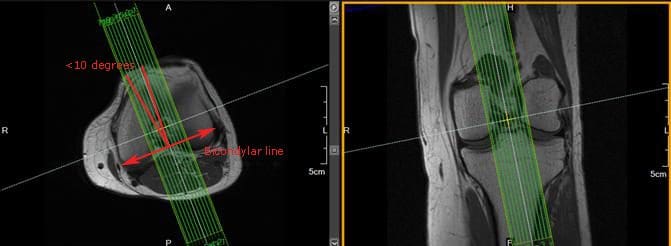

Sagittal Scans

Sagittal slices should include the anatomy from the medial condyle to the lateral condyle. The slice group may be angled per your radiologist�s preference, but should remain perpendicular to the coronal slices. Typically, the slice group is angled so that it is parallel to the medial border of the femoral condyle, as seen in the axial image in Figure 141.

Figure 141. Sagittal slice setup using axial and coronal images.

In addition to routine oblique sagittal images, some radiologists prefer an additional sagittal scan of the ACL with thin slices and high spatial resolution. Axial and coronal images can be used for slice setup. Referenced literature recommends that the angle of the slice group should not exceed 10� from a line drawn perpendicular to the bicondylar line (line that connects the posterior femoral condyles), as seen in Figure 142.

Figure 142. Sagittal ACL slice setup using axial and coronal images.

blank

References:

Kapit, Wynn, and Lawrence M. Elson. The Anatomy Coloring Book. New York: HarperCollins, 1993.

Hip Anatomy, Function, and Common Problems. (Last updated 28July2010). Retrieved from http://healthpages.org/anatomy-function/hip-structure-function-common-problems/

Cluett, J. M.D. (Updated 22May2012). Labral Tear of the Hip Joint. Retrieved from http://orthopedics.about.com/od/hipinjuries/qt/labrum.htm

Hughes, M. D.C. (15July2010). Diseases of the Femur Bone. Retrieved from http://www.livestrong.com/article/175599-diseases-of-the-femur-bone/

A Patient�s Guide to Perthes Disease of the hip. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.orthopediatrics.com/docs/Guides/perthes.html

Hip Injuries and Disorders. (Last reviewed 10February2012). Retrieved from http://nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/hipinjuriesanddisorders.html

Ligament of head of femur. (Updated 20December2011). Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ligament_of_head_of_femur

Ewing�s sarcoma. (Last modified 06January2012). Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ewing%27s_sarcoma

Hip Anatomy. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.activemotionphysio.ca/Injuries-Conditions/Hip

Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.physiotherapy-treatment.com/iliotibial-band-friction-syndrome.html

Snapping hip syndrome. (Last modified 09November2011). Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Snapping_hip_syndrome

Sekul, E. (Updated 03February2012). Meralgia Paresthetica. Retrieved from http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1141848-overview

Yeomans, S. D.C. (Updated 07July2010). Sciatic Nerve and Sciatica. Retrieved from http://www.spine-health.com/conditions/sciatica/sciatic-nerve-and-sciatica

Mayo Clinic staff. (26July2011). Meralgia paresthetica. Retrieved from http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/meralgia-paresthetica/DS00914

Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT)-Blood Clots in the Legs. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://catalog/nucleusinc.com/displaymonograph.php?MID=148

Petersilge, C. M.D. (03May2000). Chronic Adult Hip Pain: MR Arthrography of the Hip. Retrieved from http://radiographics.rsna.org/content/20/suppl_1/S43.full

Acetabular branch of medial circumflex femoral artery. (Last modified 17November2011). Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acetabular_branch_of_medial_circumflex_femoral_artery

Cluett, J. M.D. (Updated 26March2011). Hip Bursitis. Retrieved from http://orthopedics.about.com/cs/hipsurgery/a/hipbursitis.htm

Steinbach, L. M.D., Palmer, W. M.D., Schweitzer, M. M.D. (10June2002). Special Focus Session MR Arthrography. Retrieved from http://radiographics.rsna.org/content/22/5/1223.full

Schueler, S. M.D., Beckett, J.M.D., Gettings, S.M.D. (Last updated 05August2010). Ischial Bursitis/Overview. Retrieved from http://www.freemd.com/ischial-bursitis/overview.htm

Hwang, B., Fredericson, M., Chung, C., Beaulieu, C., Gold, G. (29October2004). MRI Findings of Femoral Diaphyseal Stress Injuries in Athletes. Retrieved from http://www.ajronline.org/content/185/1/166.full.pdf

The Femur (Thigh Bone). (n.d.). Retrieved from http://education.yahoo.com/reference/gray/subjects/subject/59

Norman, W. PhD, DSc. (n.d.). Joints of the Lower Limb. Retrieved from http://home.comcast.net/~wnor/lljoints.htm

Femur. (Last modified 24September2012). Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Femur

Wheeless, C. III, M.D. (Last updated 25April2012). Ligaments of Humphrey and Wrisberg. Retrieved from http://wheelessonline.com/ortho/ligaments_of_humphrey_and_wrisberg

Muscle Strains in the Thigh. (Last reviewed August2007). Retrieved from http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=A00366

Shiel, W. Jr., M.D. (Last reviewed 23July2012). Hamstring Injuries. Retrieved from http://www.medicinenet.com/hamstring_injury/article.htm

Hamstring Muscle Injuries. (Last reviewed July 2009). Retrieved from http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=a00408

Knee. (Last modified 19September2012). Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Knee

DeBerardino, T. M.D. (Updated 30March2012). Quadriceps Injury. Retrieved from http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/91473-overview

Kan, J.H. (n.d.). Osteochondral Abnormalities: Pitfalls, Injuries, and Osteochondritis Dissecans. Retrieved from http://www.arrs.org/shopARRS/products/s11p_sample.pdf

Nerves of the Lower Limb. (Last updated 30March2006). Retrieved from http://download.videohelp.com/vitualis/med/lowrnn.htm

The Adductor Canal. (Last updated 30March2006). Retrieved from http://download.videohelp.com/vitualis/med/addcanal.htm

Nabili, S. M.D. (n.d.). Varicose Veins & Spider Veins. Retrieved from http://www.medicinenet.com/varicose_veins/article.htm

Basic Venous Anatomy. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://vascular-web.com/asp/samples/sample104.asp

Femoral nerve. (Last modified 23September2012). Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Femoral_nerve

Peron, S. RDCS. (Last modified 16October2010). Anatomy � Lower Extremity Veins. Retrieved from http://www.vascularultrasound.net/vascular-anatomy/veins/lower-extremity-veins

Medical Multimedia Group, L.L.C. (n.d.). Knee Anatomy. Retrieved from http://www.eorthopod.com/content/knee-anatomy

Knee Joint Anatomy, Function and Problems. (Last updated 06July2010). Retrieved from http://healthpages.org/anatomy-function/knee-joint-structure-function-problems/

Coronary ligament of the knee. (Last modified 09May2010). Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coronary_ligament_of_the_knee

Walker, B. (n.d.). Patellar Tendonitis Treatment � Jumper�s Knee. Retrieved from http://www.thestretchinghandbook.com/archives/patellar-tendonitis.php

Osgood-Schlatter disease. (Last reviewed 12November2010). Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0002238/

Grelsamer, R. M.D. (n.d.). The Anatomy of the Patella and the Extensor Mechanism. Retrieved from http://kneehippain.com/patient_pain_anatomy.php

Oblique popliteal ligament. (Last modified 24March2012). Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oblique_popliteal_ligament

Shiel, W. Jr., M.D. (Last reviewed 27July2012). Chondromalacia Patella (Patellofemoral Syndrome). Retrieved from http://www.medicinenet.com/patellofemoral_syndrome/article.htm

Knee. (Last modified 19September2012). Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Knee

Mosher, T. M.D. (Last updated 11April2011). MRI of Knee Extensor Mechanism Injuries Overview of the Knee Extensor Mechanism. Retrieved from http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/401001-overview

Carroll, J. M.D. (December 2007). Oblique Menisco-meniscal Ligament. Retrieved from http://radsource.us/clinic/0712

DeBerardino, T. M.D. (Last updated 30March2012). Medial Collateral Knee Ligament Injury. Retrieved from http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/89890-overview#a0106

Farr, G. (Last updated 31December2007). Joints and Ligaments of the Lower Limb. Retrieved from http://becomehealthynow.com/article/bodyskeleton/951/

Knee anatomy overview. (02March2008). Retrieved from http://www.kneeguru.co.uk/KNEEnotes/node/741

Dixit, S. M.D., Difiori, J. M.D., Burton, M. M.D., Mines, B. M.D. (15January2007). Management of Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome. Retrieved from http://www.aafp.org/afp/2007/0115/p194.html

Knee Muscles. (Last updated 05September2012). Retrieved from http://www.knee-pain-explained.com/kneemuscles.html

Popliteus muscle. (Last updated 20February2012). Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Popliteus_muscle

Kneedoc. (10February2011). Nerves. Retrieved from http://thekneedoc.co.uk/neurovascular/nerves

Wheeless, C. III, M.D. (Last updated 15December2011). Popliteal Artery. Retrieved from http://wheelessonline.com/ortho/popliteal_artery

The Popliteal Artery. (n.d.) Retrieved from http://education.yahoo.com/reference/gray/subjects/subject/159

Knee bursae. (Last updated 09May2012). Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bursae_of_the_knee_joint

Hirji, Z., Hunjun, J., Choudur, H. (02May2011). Imaging of the Bursae. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3177464/

Kimaya Wellness Limited. (n.d.). Organ>Popliteal Artery. Retrieved from http://kimayahealthcare.com/OrganDetail.aspx?OrganID=103&AboutID=1

Total Vein Care. (Last updated 24February2012). Varicose Vein Anatomy and Function for Patients. Retrieved from http://www.veincare.com/education/

Tibia. (Last updated 01April2012). Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tibia

Norkus,S., Floyd, R. (Published 2001). The Anatomy and Mechanisms of Syndesmotic Ankle Sprains. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC155405/

Soleus muscle. (Last updated 10April2012). Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soleus_muscle

Achilles Tendinitis. (Last reviewed June2010). Retrieved from http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=A00147

Wheeless, C. III,M.D. (Last updated 11April2012). Sural Nerve. Retrieved from http://wheelessonline.com/ortho/sural_nerve

Medical Multimedia Group, L.L.C. (Last updated 26July2006). Ankle Syndesmosis Injuries. Retrieved from http://www.orthogate.org/patient-education/ankle/ankle-syndesmosis-injuries.html

Cluett, J. M.D. (Last updated 16September2008). Exertional Compartment Syndrome. Retrieved from http://orthopedics.about.com/od/overuseinjuries/a/compartment.htm

Leg Veins (Thigh, Lower Leg) Anatomy, Pictures and Names. (Last updated 21November2010). Retrieved from http://www.healthype.com/leg-veins-thigh-lower-leg-anatomy-pictures-and-names.html

Cluett, J.M.D. (Last updated 6October2009). Stress Fracture. Retrieved from http://orthopedics.about.com/cs/otherfractures/a/stressfracture.htm

Ostlere, S. (1December2004). Imaging the ankle and foot. Retrieved from http://imaging.birjournals.org/content/15/4/242.full

Inverarity, L. D.O. (Last updated 23January2008). Ligaments of the Ankle Joint. Retrieved from http://physicaltherapy.about.com/od/humananatomy/p/ankleligaments.htm

Golano, P., Vega, J., DeLeeuw, P., Malagelada, F.,Manzanares, M., Gotzens, V., van Dijk, C. (Published online 23March2010). Anatomy of the ankle ligaments:a pictorial essay. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2855022/

Numkarunarunrote, N., Malik, A., Aguiar, R.,Trudell, D., Resnick, D. (11October2006). Retinacula of the Foot and Ankle: MRI with Anatomic Correlation in Cadavers. Retrieved from http://www.ajronline.org/content/188/4/W348.full

Medical Multimedia Group, L.L.C. (n.d.). A Patient�s Guide to Ankle Anatomy. Retrieved from http://www.eorthopod.com/content/ankle-anatomy

The Anterior Tibial Artery. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://education.yahoo.com/reference/gray/subjects/subject/160

Foot and Ankle Anatomy. (Last updated 28July2011). Retrieved from http://northcoastfootcare.com/pages/Foot-and-Ankle-Anatomy.html

Donnelly, L., Betts, J., Fricke, B. (1July2009). Skimboarder�s Toe: Findings on High-Field MRI. Retrieved from http://www.ajronline.org/content/184/5/1481.full

Foot. (Last updated 28August2012). Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Foot

Wiley, C. (n.d.). Major Ligaments in the Foot. Retrieved from http://www.ehow.com/list_6601926_major-ligaments-foot.html

Turf Toe: Symptoms, Causes, and Treatments. (Last reviewed 9August2012). Retrieved from http://www.webmd.com/fitness-exercise/turf-toe-symptoms-causes-and-treatments

Cluett, J. M.D. (Last updated 02April2012). Turf Toe. Retrieved from http://orthopedics.about.com/od/toeproblems/p/turftoe.htm

Neurology and the Feet. (n.d.) Retrieved from http://footdoc.ca/www.FootDoc.ca/Website%20Nerves%20Of%20The%20Feet.htm

The Veins of the Lower Extremity, Abdomen, and Pelvis. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://education.yahoo.com/reference/gray/subjects/subject/173

Corley, G., Broderick, B., Nestor, S., Breen, P., Grace, P., Quondamatteo, F., O�Laighin, G. (n.d.). The Anatomy and Physiology of the Venous Foot Pump. Retrieved from http://www.eee.nuigalway.ie/documents/go_anatomy_of_the_plantar_venous_plexus_manuscript.pdf

Morton�s neuroma. (Last modified 8August2012). Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Morton%27s_metatarsalgia

References For Anatomy Pics:

Figures 1, 5, 6, 24- http://www.orthopediatrics.com/docs/Guides/perthes.html

Figures 2, 3, 11, 12, 14, 15, 16, 18, 23, 25- http://www.activemotionphysio.ca/Injuries-Conditions/Hip/Hip-Anatomy/a~299/article.html

Figure 4- http://hipkneeclinic.com/images/uploaded/hipanatomy_xray.jpg

Figures 7, 8, 9- http://hipfai.com/

Figure 10- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ewing%27s_sarcoma_MRI_nci-vol-1832-300.jpg

Figure 13- http://www.chiropractic-help.com/Patello-Femoral-Pain-Syndrome.html

Figure 17- http://www.thestretchinghandbook.com/archives/ezine_images/adductor.jpg

Figure 19- http://media.summitmedicalgroup.com/media/db/relayhealth-images/hipanat.jpg

Figures 20-22- http://www.ajronline.org/content/182/1/137.full.pdf+html

Figure 43, 44- http://radiographics.rsna.org/content/20/suppl_1/S43.full

Figure 45- http://www.exploringnature.org/db/detail.php?dbID=24&detID=2768

Figures 46-48- http://www.ajronline.org/content/185/1/166.full.pdf

Figure 49- http://arrs.org/shopARRS/products/s11p_sample.pdf

Figure 50- http://www.thestretchinghandbook.com/archives/medial-collateral-ligament.php

Figures 51, 52- http://www.radsource.us/clinic/0712

Figures 53, 54- http://www.osteo-path.co.uk/BodyMap/Thighs.html

Figure 55- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1963576/

Figure 56- http://legacy.owensboro.kctcs.edu/gcaplan/anat/Notes/API%20Notes%20M%20%20Peripheral%20Nerves.htm

Figure 57- http://www.keywordpictures.com/keyword/lateral%20cutaneous%20nerve%20of%20thigh/

Figure 58- http://home.comcast.net/~wnor/postthigh.htm

Figure 59- http://becomehealthynow.com/glossary/CONG437.htm

Figure 60- http://fitsweb.uchc.edu/student/selectives/Luzietti/Vascular_pvd.htm

Figure 61- http://www.fashion-res.com/peripheral-vascular-disease-with-stenting-in-the/

Figure 62- http://www.wpclipart.com/medical/anatomy/blood/femoral_artery_and_branches_in_leg.png.html

Figure 63- http://www.globalteleradiologyservices.com/Deep_Vein_Thrombosis_Overview.htm

Figure 64- http://www.vascularultrasound.net/vascular-anatomy/veins/lower-extremity-veins

Figure 82- http://www.jeffersonhospital.org/diseases-conditions/knee-ligament-injury.aspx?disease=658f267f-75ab-4bde-8781-f2730fafa958

Figure 83- http://javierjuan.ifunnyblog.com/anatomybackofknee/

Figure 84- http://www.kneeandshouldersurgery.com/knee-disorders/tibial-osteotomy.html

Figure 85- http://www.disease-picture.com/chondromalacia-patella-physical-therapy/

Figure 86- http://www.eorthopod.com/content/bipartite-patella

Figure 87- http://www.orthogate.org/patient-education/knee/articular-cartilage-problems-of-the-knee.html

Figure 88- http://www.webmd.com/pain-management/knee-pain/menisci-of-the-knee-joint

Figure 89- http://sumerdoc.blogspot.com/2008_07_01_archive.html

Figure 90- http://www.concordortho.com/patient-education/topic-detail-popup.aspx?topicID=55befba2d440dc8e25b85747107b5be0

Figure 91- http://trialx.com/curebyte/2011/08/16/pictures-for-chondromalacia-patella/

Figure 92- http://radiopaedia.org/images/1059

Figure 93- http://radiologycases.blogspot.com/2011/01/osgood-schlatter-disease.html

Figure 94- http://www.physioquestions.com/2010/09/07/knee-injury-acl-part-i/

Figure 95- http://www.jeffersonhospital.org/diseases-conditions/knee-ligament-injury.aspx?disease=4e3fcaf5-0145-43ea-820f-a175e586e3c8

Figures 96, 97- http://radiology.rsna.org/content/213/1/213.full

Figures 98-101- http://appliedradiology.com/Issues/2008/12/Articles/Imaging-the-knee–Ligaments.aspx

Figure 102- http://radiopaedia.org/images/408156

Figure 103- http://aftabphysio.blogspot.com/2010/08/joints-of-lower-limb.html

Figures 104, 105- http://www.radsource.us/clinic/0310

Figure 106- http://nwrunninglab.com/patellar-tendonitis.html

Figure 107- http://www.aafp.org/afp/2007/0115/p194.html

Figure 108- http://www.reboundsportspt.com/blog/tag/knee-pain

Figure 109- http://www.norwellphysicaltherapy.com/Injuries-Conditions/Knee/Knee-Issues/Quadriceps-Tendonitis-of-the-Knee/a~1803/article.html

Figure 110- http://kneeguru.co.uk/KNEEnotes/node/479

Figure 111- http://www.magicalrobot.org/BeingHuman/2010/03/fascia-bones-and-muscles

Figure 112- http://home.comcast.net/~wnor/postthigh.htm

Figures 113, 115, 157-159- http://ipodiatry.blogspot.com/2010/02/anatomy-of-foot-and-ankle_26.html

Figure 114- http://medchrome.com/basic-science/anatomy/the-knee-joint/

Figure 116- http://www.sharecare.com/question/what-are-varicose-veins

Figure 117- http://mendmyknee.com/knee-and-patella-injuries/anatomy-of-the-knee.php

Figures 118-120- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3177464/

Figure 121- http://www.riversideonline.com/health_reference/Disease-Conditions/DS00448.cfm

Figure 122- http://arthritis.ygoy.com/2011/01/01/what-is-an-arthritis-knee-cyst/

Figure 143- http://usi.edu/science/biology/mkhopper/hopper/BIOL2401/LABUNIT2/LabEx11week6/tibiaFibulaAnswer.htm

Figure 144- http://web.donga.ac.kr/ksyoo/department/education/grossanatomy/doc/html/fibula1.html

Figure 145- http://becomehealthynow.com/popups/ligaments_tib_fib_bh.htm

Figure 146- http://www.parkwayphysiotherapy.ca/article.php?aid=121

Figure 147- http://aidmyankle.com/high-ankle-sprains.php

Figure 148- http://legsonfire.wordpress.com/what-is-compartment-syndrome/

Figures 149, 152- http://www.stepbystepfootcare.ca/anatomy.html

Figures 150, 151- http://www.gla.ac.uk/ibls/US/fab/tutorial/anatomy/jiet.html

Figure 153- http://www.athletictapeinfo.com/?s=tennis+leg

Figure 154- http://radsource.us/clinic/0608

Figure 155- http://www.eorthopod.com/content/achilles-tendon-problems

Figure 156- http://achillesblog.com/assumptiondenied/not-a-rupture/

Figure 181- http://www.orthopaedicclinic.com.sg/ankle/a-patients-guide-to-ankle-anatomy/

Figure 182- http://www.activemotionphysio.ca/article.php?aid=47

Figure 183- http://www.ajronline.org/content/193/3/687.full

Figures 184, 186- http://www.eorthopod.com/content/ankle-anatomy

Figure 185- http://www.crossfitsouthbay.com/physical-therapy/learn-yourself-a-quick-anatomy-reference/ankle/

Figures 187, 227- http://www.activemotionphysio.ca/Injuries-Conditions/Foot/Foot-Anatomy/a~251/article.html

Figure 188- http://inmotiontherapy.com/article.php?aid=124

Figures 189, 190- http://home.comcast.net/~wnor/ankle.htm

Figure 191- http://skillbuilders.patientsites.com/Injuries-Conditions/Ankle/Ankle-Anatomy/a~47/article.html

Figure 192- http://metrosportsmed.patientsites.com/Injuries-Conditions/Foot/Foot-Anatomy/a~251/article.html

Figure 193- http://musc.edu/intrad/AtlasofVascularAnatomy/images/CHAP22FIG30.jpg

Figure 194- http://musc.edu/intrad/AtlasofVascularAnatomy/images/CHAP22FIG31B.jpg

Figure 195- http://veinclinics.com/physicians/appearance-of-vein-disease/

Figure 196- http://mdigradiology.com/services/interventional-services/varicose-veins.php

Figure 216- http://kidport.com/RefLib/Science/HumanBody/SkeletalSystem/Foot.htm

Figure 217- http://www.joint-pain-expert.net/foot-anatomy.html

Figure 218- http://www.thetoedoctor.com/turf-toe-symptoms-and-treatment/

Figures 219, 220- http://radsource.us/clinic/0303

Figure 221- http://www.ajronline.org/content/184/5/1481.full

Figure 222- http://www.answers.com/topic/arches

Figure 223- http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/medical/IM00939

Figure 224- http://radsource.us/clinic/0904

Figure 225- http://www.ortho-worldwide.com/anfobi.html

Figure 226- http://www.coringroup.com/lars_ligaments/patientscaregivers/your_anatomy/foot_and_ankle_anatomy/

Figure 228- http://www.stepbystepfootcare.ca/anatomy.html

Figure 229- http://iupucbio2.iupui.edu/anatomy/images/Chapt11/FG11_18aL.jpg

Figure 230- http://www.ajronline.org/content/184/5/1481.full.pdf

Figure 231- http://metrosportsmed.patientsites.com/Injuries-Conditions/Foot/Foot-Anatomy/a~251/article.html

Figure 232- http://www.painfreefeet.com/nerve-entrapments-of-the-leg-and-foot.html

Figures 233, 234- http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/401417-overview

Figure 235- http://web.squ.edu.om/med-Lib/MED_CD/E_CDs/anesthesia/site/content/v03/030676r00.HTM

Figure 236- http://www.nysora.com/peripheral_nerve_blocks/classic_block_tecniques/3035-ankle_block.html

Figure 237- http://ultrasoundvillage.net/imagelibrary/cases/?id=122&media=464&testyourself=0

Figure 238- http://www.joint-pain-expert.net/foot-anatomy.html

Figure 239- http://jap.physiology.org/content/109/4/1045.full

Figure 240- http://microsurgeon.org/secondtoe

Figure 241- http://elu.sgul.ac.uk/rehash/guest/scorm/406/package/content/common_iliac_veins.htm

Promote Healing

Promote Healing

Signs Of IT Band Syndrome

Signs Of IT Band Syndrome If you are a runner, you will be able to distinguish ITBS by:

If you are a runner, you will be able to distinguish ITBS by: If you want to do away with pain, you might consider looking for a fit pair of shoes as they will reduce any pain, causing issues in the long run. Pay attention to small specifics like shoes that offer enough heel space, sufficient toe box room, and enough space for wide feet. Your toes should be able to move freely without being constricted.

If you want to do away with pain, you might consider looking for a fit pair of shoes as they will reduce any pain, causing issues in the long run. Pay attention to small specifics like shoes that offer enough heel space, sufficient toe box room, and enough space for wide feet. Your toes should be able to move freely without being constricted. This upgraded version is lightweight to help with any knee problems. It offers you comfort through cushioning that help absorb shock as you run as well as other features like grip, fit, and durability. The shoe has an added outer sole to ensure it lasts you as long as possible.

This upgraded version is lightweight to help with any knee problems. It offers you comfort through cushioning that help absorb shock as you run as well as other features like grip, fit, and durability. The shoe has an added outer sole to ensure it lasts you as long as possible. It tops the list of 5 best running shoes. Also, it has remained the first choice for most runners with knee pain issues. This pair offers all the above functionalities too, making it your best choice.

It tops the list of 5 best running shoes. Also, it has remained the first choice for most runners with knee pain issues. This pair offers all the above functionalities too, making it your best choice. Puma models have never disappointed, and this one is no exception. Puma Faas 600 is the solution to your knee pain. It is also an affordable option for the short-handed.

Puma models have never disappointed, and this one is no exception. Puma Faas 600 is the solution to your knee pain. It is also an affordable option for the short-handed. This is another great choice on the list. It is one of the New Balance Fresh Foam Series. Its midsole offers you the required support coupled with comfort to eliminate knee pains.

This is another great choice on the list. It is one of the New Balance Fresh Foam Series. Its midsole offers you the required support coupled with comfort to eliminate knee pains. This is the 16th edition of the Saucony Hurricane, which offers a combination of steadiness and protection. Those with knee pain have agreed with the stability offered by this shoe. It is also cushioned to help you go for long runs without any pain or injury. It is perfect for heavy runners and those who are out of shape due to inactivity.

This is the 16th edition of the Saucony Hurricane, which offers a combination of steadiness and protection. Those with knee pain have agreed with the stability offered by this shoe. It is also cushioned to help you go for long runs without any pain or injury. It is perfect for heavy runners and those who are out of shape due to inactivity.

Individuals who sit most of the day, like those working in a computer while sitting in an office chair, are also at high risk for non-accidental spine injury. Office ergonomics, or computer ergonomics, can help minimize the risk such as the dangers associated with prolonged sitting in an office chair, and carpal tunnel syndrome, such as lower back pain, neck strain, and leg pain.

Individuals who sit most of the day, like those working in a computer while sitting in an office chair, are also at high risk for non-accidental spine injury. Office ergonomics, or computer ergonomics, can help minimize the risk such as the dangers associated with prolonged sitting in an office chair, and carpal tunnel syndrome, such as lower back pain, neck strain, and leg pain. Many potentially harmful situations that lead to back injury can be identified and avoided by following four basic rules of thumb:

Many potentially harmful situations that lead to back injury can be identified and avoided by following four basic rules of thumb: These ergonomic rules of thumb will help the worker and their backs. Otherwise the worker is at risk of sustaining or aggravating a

These ergonomic rules of thumb will help the worker and their backs. Otherwise the worker is at risk of sustaining or aggravating a