by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Back Pain, Chiropractic, Chronic Back Pain, Chronic Pain, Health, Herniated Disc, Lower Back Pain, Neck Pain, Sciatica, Sciatica Nerve Pain, Scoliosis, Spinal Hygiene, Spine Care, Treatments, Wellness

Degenerative Disc Disease is a general term for a condition in which the damaged intervertebral disc causes chronic pain, which could be either low back pain in the lumbar spine or neck pain in the cervical spine. It is not a �disease� per se, but actually a breakdown of an intervertebral disc of the spine. The intervertebral disc is a structure that has a lot of attention being focused on recently, due to its clinical implications. The pathological changes that can occur in disc degeneration include fibrosis, narrowing, and disc desiccation. Various anatomical defects can also occur in the intervertebral disc such as sclerosis of the endplates, fissuring and mucinous degeneration of the annulus, and the formation of osteophytes.

Low back pain and neck pain are major epidemiological problems, which are thought to be related to degenerative changes in the disk. Back pain is the second leading cause of the visit to the clinician in the USA. It is estimated that about 80% of US adults suffer from low back pain at least once during their lifetime. (Modic, Michael T., and Jeffrey S. Ross) Therefore, a thorough understanding of degenerative disc disease is needed for managing this common condition.

Anatomy of Related Structures

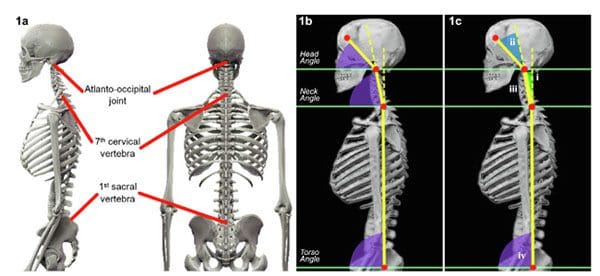

Anatomy of the Spine

The spine is the main structure, which maintains the posture and gives rise to various problems with disease processes. The spine is composed of seven cervical vertebrae, twelve thoracic vertebrae, five lumbar vertebrae, and fused sacral and coccygeal vertebrae. The stability of the spine is maintained by three columns.

The anterior column is formed by anterior longitudinal ligament and the anterior part of the vertebral body. The middle column is formed by the posterior part of the vertebral body and the posterior longitudinal ligament. The posterior column consists of a posterior body arch that has transverse processes, laminae, facets, and spinous processes. (�Degenerative Disk Disease: Background, Anatomy, Pathophysiology�)

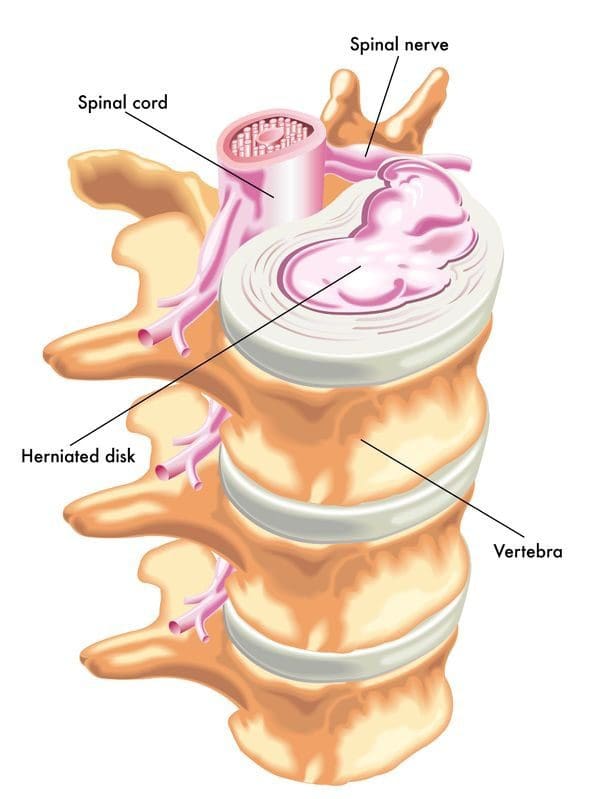

Anatomy of the Intervertebral Disc

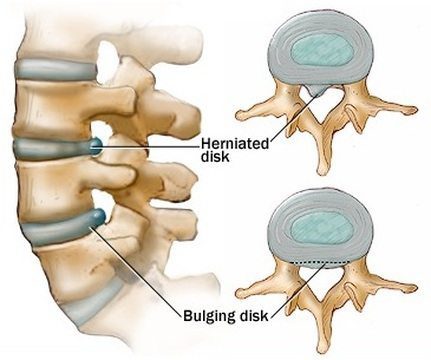

Intervertebral disc lies between two adjacent vertebral bodies in the vertebral column. About one-quarter of the total length of the spinal column is formed by intervertebral discs. This disc forms a fibrocartilaginous joint, also called a symphysis joint. It allows a slight movement in the vertebrae and holds the vertebrae together. Intervertebral disc is characterized by its tension resisting and compression resisting qualities. An intervertebral disc is composed of mainly three parts; inner gelatinous nucleus pulposus, outer annulus fibrosus, and cartilage endplates that are located superiorly and inferiorly at the junction of vertebral bodies.

Nucleus pulposus is the inner part that is gelatinous. It consists of proteoglycan and water gel held together by type II Collagen and elastin fibers arranged loosely and irregularly. Aggrecan is the major proteoglycan found in the nucleus pulposus. It comprises approximately 70% of the nucleus pulposus and nearly 25% of the annulus fibrosus. It can retain water and provides the osmotic properties, which are needed to resist compression and act as a shock absorber. This high amount of aggrecan in a normal disc allows the tissue to support compressions without collapsing and the loads are distributed equally to annulus fibrosus and vertebral body during movements of the spine. (Wheater, Paul R, et al.)

The outer part is called annulus fibrosus, which has abundant type I collagen fibers arranged as a circular layer. The collagen fibers run in an oblique fashion between lamellae of the annulus in alternating directions giving it the ability to resist tensile strength. Circumferential ligaments reinforce the annulus fibrosus peripherally. On the anterior aspect, a thick ligament further reinforces annulus fibrosus and a thinner ligament reinforces the posterior side. (Choi, Yong-Soo)

Usually, there is one disc between every pair of vertebrae except between atlas and axis, which are first and second cervical vertebrae in the body. These discs can move about 6? in all the axes of movement and rotation around each axis. But this freedom of movement varies between different parts of the vertebral column. The cervical vertebrae have the greatest range of movement because the intervertebral discs are larger and there is a wide concave lower and convex upper vertebral body surfaces. They also have transversely aligned facet joints. Thoracic vertebrae have the minimum range of movement in flexion, extension, and rotation, but have free lateral flexion as they are attached to the rib cage. The lumbar vertebrae have good flexion and extension, again, because their intervertebral discs are large and spinous processes are posteriorly located. However, lateral lumbar rotation is limited because the facet joints are located sagittally. (�Degenerative Disk Disease: Background, Anatomy, Pathophysiology�)

Blood Supply

The intervertebral disc is one of the largest avascular structures in the body with capillaries terminating at the endplates. The tissues derive nutrients from vessels in the subchondral bone which lie adjacent to the hyaline cartilage at the endplate. These nutrients such as oxygen and glucose are carried to the intervertebral disc through simple diffusion. (�Intervertebral Disc � Spine � Orthobullets.Com�)

Nerve Supply

Sensory innervation of intervertebral discs is complex and varies according to the location in the spinal column. Sensory transmission is thought to be mediated by substance P, calcitonin, VIP, and CPON. Sinu vertebral nerve, which arises from the dorsal root ganglion, innervates the superficial fibers of the annulus. Nerve fibers don�t extend beyond the superficial fibers.

Lumbar intervertebral discs are additionally supplied on the posterolateral aspect with branches from ventral primary rami and from the grey rami communicantes near their junction with the ventral primary rami. The lateral aspects of the discs are supplied by branches from rami communicantes. Some of the rami communicantes may cross the intervertebral discs and become embedded in the connective tissue, which lies deep to the origin of the psoas. (Palmgren, Tove, et al.)

The cervical intervertebral discs are additionally supplied on the lateral aspect by branches of the vertebral nerve. The cervical sinu vertebral nerves were also found to be having an upward course in the vertebral canal supplying the disc at their point of entry and the one above. (BOGDUK, NIKOLAI, et al.)

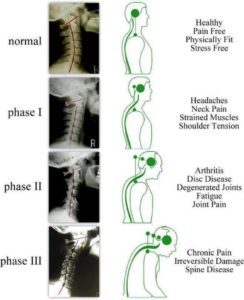

Pathophysiology of Degenerative Disc Disease

Approximately 25% of people before the age of 40 years show disc degenerative changes at some level. Over 40 years of age, MRI evidence shows changes in more than 60% of people. (Suthar, Pokhraj) Therefore, it is important to study the degenerative process of the intervertebral discs as it has been found to degenerate faster than any other connective tissue in the body, leading to back and neck pain. The changes in three intervertebral discs are associated with changes in the vertebral body and joints suggesting a progressive and dynamic process.

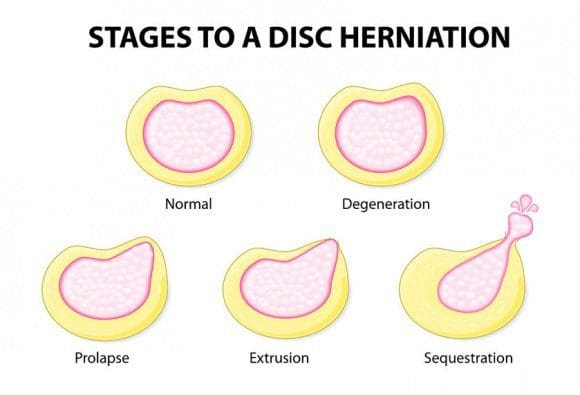

The degenerative process of the intervertebral discs has been divided into three stages, according to Kirkaldy-Willis and Bernard, called ��degenerative cascade��. These stages can overlap and can occur over the course of decades. However, identifying these stages clinically is not possible due to the overlap of symptoms and signs.

Stage 1 (Degeneration Phase)

This stage is characterized by degeneration. There are histological changes, which show circumferential tears and fissures in the annulus fibrosus. These circumferential tears may turn into radial tears and because the annulus pulposus is well innervated, these tears can cause back pain or neck pain, which is localized and with painful movements. Due to repeated trauma in the discs, endplates can separate leading to disruption of the blood supply to the disc and therefore, depriving it of its nutrient supply and removal of waste. The annulus may contain micro-fractures in the collagen fibrils, which can be seen on electron microscopy and an MRI scan may reveal desiccation, bulging of the disc, and a high-intensity zone in the annulus. Facet joints may show a synovial reaction and it may cause severe pain with associated synovitis and inability to move the joint in the zygapophyseal joints. These changes may not necessarily occur in every person. (Gupta, Vijay Kumar, et al.)

The nucleus pulposus is also involved in this process as its water imbibing capacity is reduced due to the accumulation of biochemically changed proteoglycans. These changes are brought on mainly by two enzymes called matrix metalloproteinase-3 (MMP-3) and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1). (Bhatnagar, Sushma, and Maynak Gupta) Their imbalance leads to the destruction of proteoglycans. The reduced capacity to absorb water leads to a reduction of hydrostatic pressure in the nucleus pulposus and causes the annular lamellae to buckle. This can increase the mobility of that segment resulting in shear stress to the annular wall. All these changes can lead to a process called annular delamination and fissuring in the annulus fibrosus. These are two separate pathological processes and both can lead to pain, local tenderness, hypomobility, contracted muscles, painful joint movements. However, the neurological examination at this stage is usually normal.

Stage 2 (Phase of Instability)

The stage of dysfunction is followed by a stage of instability, which may result from the progressive deterioration of the mechanical integrity of the joint complex. There may be several changes encountered at this stage, including disc disruption and resorption, which can lead to a loss of disc space height. Multiple annular tears may also occur at this stage with concurrent changes in the zagopophyseal joints. They may include degeneration of the cartilage and facet capsular laxity leading to subluxation. These biomechanical changes result in instability of the affected segment.

The symptoms seen in this phase are similar to those seen in the dysfunction phase such as �giving way� of the back, pain when standing for prolonged periods, and a �catch� in the back with movements. They are accompanied by signs such as abnormal movements in the joints during palpation and observing that the spine sways or shifts to a side after standing erect for sometime after flexion. (Gupta, Vijay Kumar et al.)

Stage 3 (Re-Stabilization Phase)

In this third and final stage, the progressive degeneration leads to disc space narrowing with fibrosis and osteophyte formation and transdiscal bridging. The pain arising from these changes is severe compared to the previous two stages, but these can vary between individuals. This disc space narrowing can have several implications on the spine. This can cause the intervertebral canal to narrow in the superior-inferior direction with the approximation of the adjacent pedicles. Longitudinal ligaments, which support the vertebral column, may also become deficient in some areas leading to laxity and spinal instability. The spinal movements can cause the ligamentum flavum to bulge and can cause superior aricular process subluxation. This ultimately leads to a reduction of diameter in the anteroposterior direction of the intervertebral space and stenosis of upper nerve root canals.

Formation of osteophytes and hypertrophy of facets can occur due to the alteration in axial load on the spine and vertebral bodies. These can form on both superior and inferior articular processes and osteophytes can protrude to the intervertebral canal while the hypertrophied facets can protrude to the central canal. Osteophytes are thought to be made from the proliferation of articular cartilage at the periosteum after which they undergo endochondral calcification and ossification. The osteophytes are also formed due to the changes in oxygen tension and due to changes in fluid pressure in addition to load distribution defects. The osteophytes and periarticular fibrosis can result in stiff joints. The articular processes may also orient in an oblique direction causing retrospondylolisthesis leading to the narrowing of the intervertebral canal, nerve root canal, and the spinal canal. (KIRKALDY-WILLIS, W H et al.)

All of these changes lead to low back pain, which decreases with severity. Other symptoms like reduced movement, muscle tenderness, stiffness, and scoliosis can occur. The synovial stem cells and macrophages are involved in this process by releasing growth factors and extracellular matrix molecules, which act as mediators. The release of cytokines has been found to be associated with every stage and may have therapeutic implications in future treatment development.

Etiology of the Risk Factors of Degenerative Disc Disease

Aging and Degeneration

It is difficult to differentiate aging from degenerative changes. Pearce et al have suggested that aging and degeneration is representing successive stages within a single process that occur in all individuals but at different rates. Disc degeneration, however, occurs most often at a faster rate than aging. Therefore, it is encountered even in patients of working age.

There appears to be a relationship between aging and degeneration, but no distinct cause has yet been established. Many studies have been conducted regarding nutrition, cell death, and accumulation of degraded matrix products and the failure of the nucleus. The water content of the intervertebral disc decreases with the increasing age. Nucleus pulposus can get fissures that can extend into the annulus fibrosus. The start of this process is termed chondrosis inter vertebralis, which can mark the beginning of the degenerative destruction of the intervertebral disc, the endplates, and the vertebral bodies. This process causes complex changes in the molecular composition of the disc and has biomechanical and clinical sequelae that can often result in substantial impairment in the affected individual.

The cell concentration in the annulus decreases with increasing age. This is mainly because the cells in the disc are subjected to senescence and they lose the ability to proliferate. Other related causes of age-specific degeneration of intervertebral discs include cell loss, reduced nutrition, post-translational modification of matrix proteins, accumulation of products of degraded matrix molecules, and fatigue failure of the matrix. Decreasing nutrition to the central disc, which allows the accumulation of cell waste products and degraded matrix molecules seems to be the most important change out of all these changes. This impairs nutrition and causes a fall in the pH level, which can further compromise cell function and may lead to cell death. Increased catabolism and decreased anabolism of senescent cells may promote degeneration. (Buckwalter, Joseph A.) According to one study, there were more senescence cells in the nucleus pulposus compared to annulus fibrosus and herniated discs had a higher chance of cell senescence.� (Roberts, S. et al.)

When the aging process goes on for some time, the concentrations of chondroitin 4 sulfate and chondroitin 5 sulfate, which is strongly hydrophilic, gets decreased while the keratin sulfate to chondroitin sulfate ratio gets increased. Keratan sulfate is mildly hydrophilic and it also has a minor tendency to form stable aggregates with hyaluronic acid. As aggrecan is fragmented, and its molecular weight and numbers are decreased, the viscosity and hydrophilicity of the nucleus pulposus decrease. Degenerative changes to the intervertebral discs are accelerated by the reduced hydrostatic pressure of the nucleus pulposus and the decreased supply of nutrients by diffusion. When the water content of the extracellular matrix is decreased, intervertebral disc height will also be decreased. The resistance of the disc to an axial load will also be reduced. Because the axial load is then transferred directly to the annulus fibrosus, annulus clefts can get torn easily.

All these mechanisms lead to structural changes seen in degenerative disc disease. Due to the reduced water content in the annulus fibrosus and associated loss of compliance, the axial load can get redistributed to the posterior aspect of facets instead of the normal anterior and middle part of facets. This can cause facet arthritis, hypertrophy of the adjacent vertebral bodies, and bony spurs or bony overgrowths, known as osteophytes, as a result of degenerative discs. (Choi, Yong-Soo)

Genetics and Degeneration

The genetic component has been found to be a dominant factor in degenerative disc disease. Twin studies, and studies involving mice, have shown that genes play a role in disc degeneration. (Boyd, Lawrence M., et al.) Genes that code for collagen I, IX, and XI, interleukin 1, aggrecan, vitamin D receptor, matrix metalloproteinase 3 (MMP � 3), and other proteins are among the genes that are suggested to be involved in degenerative disc disease. Polymorphisms in 5 A and 6 A alleles occurring in the promoter region of genes that regulate MMP 3 production are found to be a major factor for the increased lumbar disc degeneration in the elderly population. Interactions among these various genes contribute significantly to intervertebral disc degeneration disease as a whole.

Nutrition and Degeneration

Disc degeneration is also believed to occur due to the failure of nutritional supply to the intervertebral disc cells. Apart from the normal aging process, the nutritional deficiency of the disc cells is adversely affected by endplate calcification, smoking, and the overall nutritional status. Nutritional deficiency can lead to the formation of lactic acid together with the associated low oxygen pressure. The resulting low pH can affect the ability of disc cells to form and maintain the extracellular matrix of the discs and causes intervertebral disc degeneration. The degenerated discs lack the ability to respond normally to the external force and may lead to disruptions even from the slightest back strain. (Taher, Fadi, et al.)

Growth factors stimulate the chondrocytes and fibroblasts to produce more amount of extracellular matrix. It also inhibits the synthesis of matrix metalloproteinases. Example of these growth factors includes transforming growth factor, insulin-like growth factor, and basic fibroblast growth factor. The degraded matrix is repaired by an increased level of transforming growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor.

Environment and Degeneration

Even though all the discs are of the same age, discs found in the lower lumbar segments are more vulnerable to degenerative changes than the discs found in the upper segment. This suggests that not only aging but, also mechanical loading, is a causative factor. The association between degenerative disc disease and environmental factors has been defined in a comprehensive manner by Williams and Sambrook in 2011. (Williams, F.M.K., and P.N. Sambrook) The heavy physical loading associated with your occupation is a risk factor that has some contribution to disc degenerative disease. There is also a possibility of chemicals causing disc degeneration, such as smoking, according to some studies. (Batti�, Michele C.) Nicotine has been implicated in twin studies to cause impaired blood flow to the intervertebral disc, leading to disc degeneration. (BATTI�, MICHELE C., et al.) Moreover, an association has been found among atherosclerotic lesions in the aorta and the low back pain citing a link between atherosclerosis and degenerative disc disease. (Kauppila, L.I.) The disc degeneration severity was implicated in overweight, obesity, metabolic syndrome, and increased body mass index in some studies. (�A Population-Based Study Of Juvenile Disc Degeneration And Its Association With Overweight And Obesity, Low Back Pain, And Diminished Functional Status. Samartzis D, Karppinen J, Mok F, Fong DY, Luk KD, Cheung KM. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011;93(7):662�70�)

Pain in Disc Degeneration (Discogenic Pain)

Discogenic pain, which is a type of nociceptive pain, arises from the nociceptors in the annulus fibrosus when the nervous system is affected by the degenerative disc disease. Annulus fibrosus contains immune reactive nerve fibers in the outer layer of the disc with other chemicals such as a vasoactive intestinal polypeptide, calcitonin gene-related peptide, and substance P. (KONTTINEN, YRJ� T., et al.) When degenerative changes in the intervertebral discs occur, normal structure and mechanical load are changed leading to abnormal movements. These disc nociceptors can get abnormally sensitized to mechanical stimuli. The pain can also be provoked by the low pH environment caused by the presence of lactic acid, causing increased production of pain mediators.

Pain from degenerative disc disease may arise from multiple origins. It may occur due to the structural damage, pressure, and irritation on the nerves in the spine. The disc itself contains only a few nerve fibers, but any injury can sensitize these nerves, or those in the posterior longitudinal ligament, to cause pain. Micro movements in the vertebrae can occur, which may cause painful reflex muscle spasms because the disc is damaged and worn down with the loss of tension and height. The painful movements arise because the nerves supplying the area are compressed or irritated by the facet joints and ligaments in the foramen leading to leg and back pain. This pain may be aggravated by the release of inflammatory proteins that act on nerves in the foramen or descending nerves in the spinal canal.

Pathological specimens of the degenerative discs, when observed under the microscope, reveals that there are vascularized granulation tissue and extensive innervations found in the fissures of the outer layer of the annulus fibrosus extending into the nucleus pulposus. The granulation tissue area is infiltrated by abundant mast cells and they invariably contribute to the pathological processes that ultimately lead to discogenic pain. These include neovascularisation, intervertebral disc degeneration, disc tissue inflammation, and the formation of fibrosis. Mast cells also release substances, such as tumor necrosis factor and interleukins, which might signal for the activation of some pathways which play a role in causing back pain. Other substances that can trigger these pathways include phospholipase A2, which is produced from the arachidonic acid cascade. It is found in increased concentrations in the outer third of the annulus of the degenerative disc and is thought to stimulate the nociceptors located there to release inflammatory substances to trigger pain. These substances bring about axonal injury, intraneural edema, and demyelination. (Brisby, Helena)

The back pain is thought to arise from the intervertebral disc itself. Hence why the pain will decrease gradually over time when the degenerating disc stops inflicting pain. However, the pain actually arises from the disc itself only in 11% of patients according to endoscopy studies. The actual cause of back pain seems to be due to the stimulation of the medial border of the nerve and referred pain along the arm or leg seems to arise due to the stimulation of the core of the nerve. The treatment for disc degeneration should mainly focus on pain relief to reduce the suffering of the patient because it is the most disabling symptom that disrupts a patient�s lives. Therefore, it is important to establish the mechanism of pain because it occurs not only due to the structural changes in the intervertebral discs but also due to other factors such as the release of chemicals and understanding these mechanisms can lead to effective pain relief. (Choi, Yong-Soo)

Clinical Presentation of Degenerative Disc Disease

Patients with degenerative disc disease face a myriad of symptoms depending on the site of the disease. Those who have lumbar disc degeneration get low back pain, radicular symptoms, and weakness. Those who have cervical disc degeneration have neck pain and shoulder pain.

Low back pain can get exacerbated by the movements and the position. Usually, the symptoms are worsened by the flexion, while the extension often relieves them. Minor twisting injuries, even from swinging a golf club, can trigger the symptoms. The pain is usually observed to be less when walking or running, when changing the position frequently and when lying down. However, the pain is usually subjective and in many cases, it varies considerably from person to person and most people will suffer from a low level of chronic pain of the lower back region continuously while occasionally suffering from the groin, hip, and leg pain. The intensity of the pain will increase from time to time and will last for a few days and then subside gradually. This �flare-up� is an acute episode and needs to be treated with potent analgesics. Worse pain is experienced in the seated position and is exacerbated while bending, lifting, and twisting movements frequently. The severity of the pain can vary considerably with some having occasional nagging pain to others having severe and disabling pain intermittently.� (Jason M. Highsmith, MD)

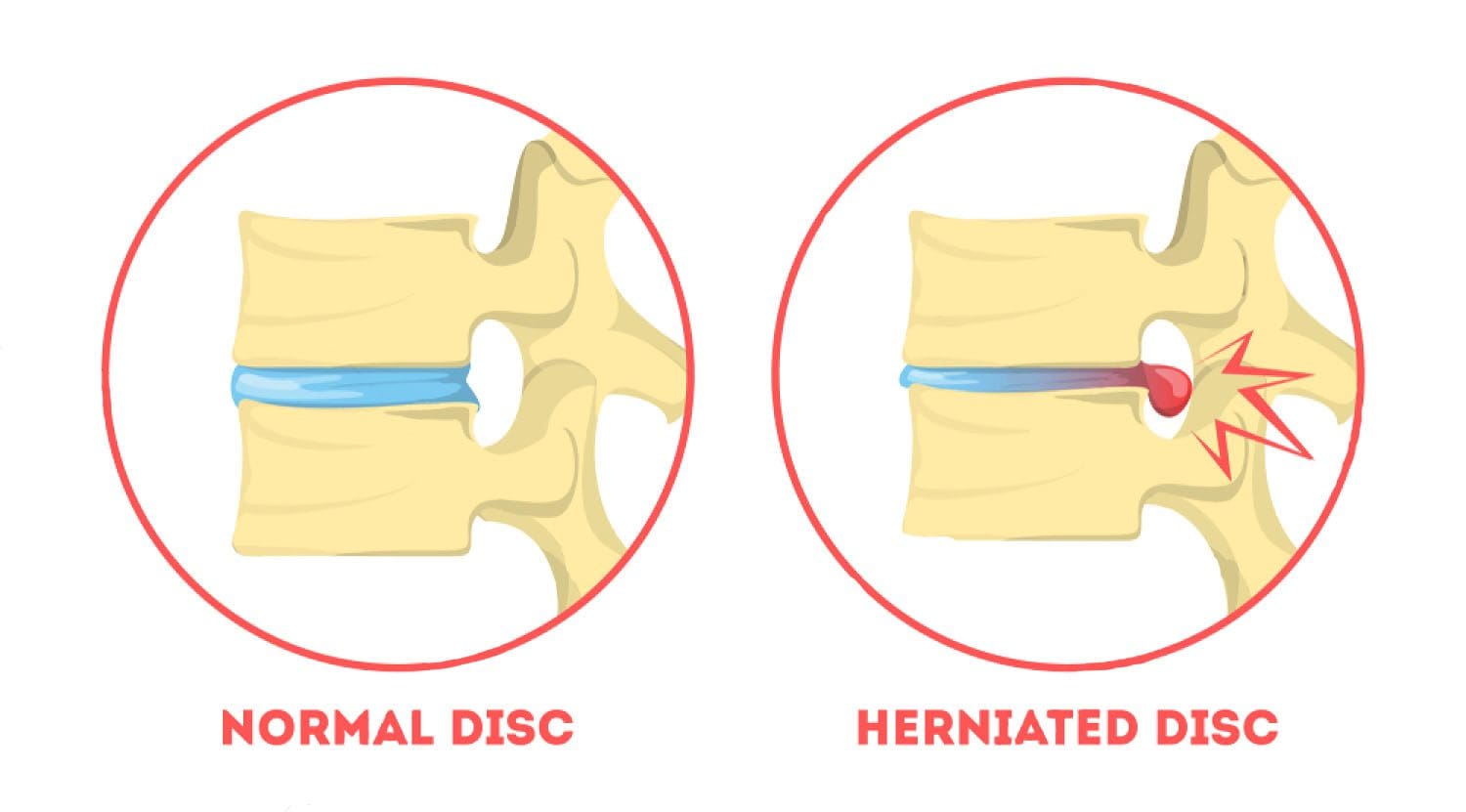

The localized pain and tenderness in the axial spine usually arises from the nociceptors found within the intervertebral discs, facet joints, sacroiliac joints, dura mater of the nerve roots, and the myofascial structures found within the axial spine. As mentioned in the previous sections, the degenerative anatomical changes may result in a narrowing of the spinal canal called spinal stenosis, overgrowth of spinal processes called osteophytes, hypertrophy of the inferior and superior articular processes, spondylolisthesis, bulging of the ligamentum flavum and disc herniation. These changes result in a collection of symptoms that is known as neurogenic claudication. There may be symptoms such as low back pain and leg pain together with numbness or tingling in the legs, muscle weakness, and foot drop. Loss of bowel or bladder control may suggest spinal cord impingement and prompt medical attention is needed to prevent permanent disabilities. These symptoms can vary in severity and may present to varying extents in different individuals.

The pain can also radiate to other parts of the body due to the fact that the spinal cord gives off several branches to two different sites of the body. Therefore, when the degenerated disc presses on a spinal nerve root, the pain can also be experienced in the leg to which the nerve ultimately innervates. This phenomenon, called radiculopathy, can occur from many sources arising, due to the process of degeneration. The bulging disc, if protrudes centrally, can affect descending rootlets of the cauda equina, if it bulges posterolaterally, it might affect the nerve roots exiting at the next lower intervertebral canal and the spinal nerve within its ventral ramus can get affected when the disc protrudes laterally. Similarly, the osteophytes protruding along the upper and lower margins of the posterior aspect of vertebral bodies can impinge on the same nervous tissues causing the same symptoms. Superior articular process hypertrophy may also impinge upon nerve roots depending on their projection. The nerves may include nerve roots prior to exiting from the next lower intervertebral canal and nerve roots within the upper nerve root canal and dural sac. These symptoms, due to the nerve impingement, have been proven by cadaver studies. Neural compromise is thought to occur when the neuro foraminal diameter is critically occluded with a 70% reduction. Furthermore, neural compromise can be produced when the posterior disc is compressed less than 4 millimeters in height, or when the foraminal height is reduced to less than 15 millimeters leading to foraminal stenosis and nerve impingement. (Taher, Fadi, et al.)

Diagnostic Approach

Patients are initially evaluated with an accurate history and thorough physical examination and appropriate investigations and provocative testing. However, history is often vague due to the chronic pain which cannot be localized properly and the difficulty in determining the exact anatomical location during provocative testing due to the influence of the neighboring anatomical structures.

Through the patient�s history, the cause of low back pain can be identified as arising from the nociceptors in the intervertebral discs. Patients may also give a history of the chronic nature of the symptoms and associated gluteal region numbness, tingling as well as stiffness in the spine which usually worsens with activity. Tenderness may be elicited by palpating over the spine. Due to the nature of the disease being chronic and painful, most patients may be suffering from mood and anxiety disorders. Depression is thought to be contributing negatively to the disease burden. However, no clear relationship between disease severity and mood or anxiety disorders. It is good to be vigilant about these mental health conditions as well. In order to exclude other serious pathologies, questions must be asked regarding fatigue, weight loss, fever, and chills, which might indicate some other diseases. (Jason M. Highsmith, MD)

Another etiology for the low back pain has to be excluded when examining the patient for degenerative disc disease. Abdominal pathologies, which can give rise to back pain such as aortic aneurysm, renal calculi, and pancreatic disease, have to be excluded.

Degenerative disc disease has several differential diagnoses to be considered when a patient presents with back pain. These include; idiopathic low back pain, zygapophyseal joint degeneration, myelopathy, lumbar stenosis, spondylosis, osteoarthritis, and lumbar radiculopathy. (�Degenerative Disc Disease � Physiopedia�)

Investigations

Investigations are used to confirm the diagnosis of degenerative disc disease. These can be divided into laboratory studies, imaging studies, nerve conduction tests, and diagnostic procedures.

Imaging Studies

The imaging in degenerative disc disease is mainly used to describe anatomical relations and morphological features of the affected discs, which has a great therapeutic value in future decision making for treatment options. Any imaging method, like plain radiography, CT, or MRI, can provide useful information. However, an underlying cause can only be found in 15% of the patients as no clear radiological changes are visible in degenerative disc disease in the absence of disc herniation and neurological deficit. Moreover, there is no correlation between the anatomical changes seen on imaging and the severity of the symptoms, although there are correlations between the number of osteophytes and the severity of back pain. Degenerative changes in radiography can also be seen in asymptomatic people leading to difficulty in conforming clinical relevance and when to start treatment. (�Degenerative Disc Disease � Physiopedia�)

Plain Radiography

This inexpensive and widely available plain cervical radiography can give important information on deformities, alignment, and degenerative bony changes. In order to determine the presence of spinal instability and sagittal balance, dynamic flexion, or extension studies have to be performed.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

MRI is the most commonly used method to diagnose degenerative changes in the intervertebral disc accurately, reliably, and most comprehensively. It is used in the initial evaluation of patients with neck pain after plain radiography. It can provide non-invasive images in multiple plains and gives excellent quality images of the disc. MRI can show disc hydration and morphology-based on the proton density, chemical environment, and the water content. Clinical picture and history of the patient have to be considered when interpreting MRI reports as it has been shown that as much as 25% of radiologists change their report when the clinical data are available. Fonar produced the first open MRI scanner with the ability of the patient to be scanned in different positions such as standing, sitting, and bending. Because of these unique features, this open MRI scanner can be used for scanning patients in weight-bearing postures and stand up postures to detect underlying pathological changes which are usually overlooked in conventional MRI scan such as lumbar degenerative disc disease with herniation. This machine is also good for claustrophobic patients, as they get to watch a large television screen during the scanning process. (�Degenerative Disk Disease: Background, Anatomy, Pathophysiology.�)

Nucleus pulposus and annulus fibrosus of the disc can usually be identified on MRI, leading to the detection of disc herniation as contained and non contained. As MRI can also show annular tears and the posterior longitudinal ligament, it can be used to classify herniation. This can be simple annular bulging to free fragment disc herniations. This information can describe the pathologic discs such as extruded disc, protruded discs, and migrated discs.

There are several grading systems based on MRI signal intensity, disc height, the distinction between nucleus and annulus, and the disc structure. The method, by Pfirrmann et al, has been widely applied and clinically accepted. According to the modified system, there are 8 grades for lumbar disc degenerative disease. Grade 1 represents normal intervertebral disc and grade 8 corresponds to the end stage of degeneration, depicting the progression of the disc disease. There are corresponding images to aid the diagnosis. As they provide good tissue differentiation and detailed description of the disc structure, sagittal T2 weighted images are used for the classification purpose. (Pfirrmann, Christian W. A., et al.)

Modic has described the changes occurring in the vertebral bodies adjacent to the degenerating discs as Type 1 and Type 2 changes. In Modic 1 changes, there is decreased intensity of T1 weighted images and increased intensity T2 weighted images. This is thought to occur because the end plates have undergone sclerosis and the adjacent bone marrow is showing inflammatory response as the diffusion coefficient increases. This increase of diffusion coefficient and the ultimate resistance to diffusion is brought about by the chemical substances released through an autoimmune mechanism. Modic type 2 changes include the destruction of the bone marrow of adjacent vertebral endplates due to an inflammatory response and the infiltration of fat in the marrow. These changes may lead to increased signal density on T1 weighted images. (Modic, M T et al.)

Computed Tomography (CT)

When MRI is not available, Computed tomography is considered a diagnostic test that can detect disc herniation because it has a better contrast between posterolateral margins of the adjacent bony vertebrae, perineal fat, and the herniated disc material. Even so, when diagnosing lateral herniations, MRI remains the imaging modality of choice.

CT scan has several advantages over MRI such as it has a less claustrophobic environment, low cost, and better detection of bonny changes that are subtle and may be missed on other modalities. CT can detect early degenerative changes of the facet joints and spondylosis with more accuracy. Bony integrity after fusion is also best assessed by CT.

Disc herniation and associated nerve impingement can be diagnosed by using the criteria developed by Gundry and Heithoff. It is important for the disc protrusion to lie directly over the nerve roots traversing the disc and to be focal and asymmetrical with a dorsolateral position. There should be demonstrable nerve root compression or displacement. Lastly, the nerve distal to the impingement (site of herniation) often enlarges and bulges with resulting edema, prominence of adjacent epidural veins, and inflammatory exudates resulting in blurring the margin.

Lumbar Discography

This procedure is controversial and, whether knowing the site of the pain has any value regarding surgery or not, has not been proven. False positives can occur due to central hyperalgesia in patients with chronic pain (neurophysiologic finding) and due to psychosocial factors. It is questionable to establish exactly when discogenic pain becomes clinically significant. Those who support this investigation advocates strict criteria for selection of the patients and when interpreting results and believe this is the only test that can diagnose discogenic pain. Lumbar discography can be used in several situations, although it is not scientifically established. These include; diagnosis of lateral herniation, diagnosing a symptomatic disc among multiple abnormalities, assessing similar abnormalities seen on CT or MRI, evaluation of the spine after surgery, selection of fusion level, and the suggestive features of discogenic pain existence.

The discography is more concerned about eliciting pathophysiology rather than determining the anatomy of the disc. Therefore, discogenic pain evaluation is the aim of discography. MRI may reveal an abnormally looking disc with no pain, while severe pain may be seen on discography where MRI findings are few. During the injection of normal saline or the contrast material, a spongy endpoint can occur with abnormal discs accepting more amounts of contrast. The contrast material can extend into the nucleus pulposus through tears and fissures in the annulus fibrosus in the abnormal discs. The pressure of this contrast material can provoke pain due to the innervations by recurrent meningeal nerve, mixed spinal nerve, anterior primary rami, and gray rami communicantes supplying the outer annulus fibrosus. Radicular pain can be provoked when the contrast material reaches the site of nerve root impingement by the abnormal disc. However, this discography test has several complications such as nerve root injury, chemical or bacterial diskitis, contrast allergy, and the exacerbation of pain. (Bartynski, Walter S., and A. Orlando Ortiz)

Imaging Modality Combination

In order to evaluate the nerve root compression and cervical stenosis adequately, a combination of imaging methods may be needed.

CT Discography

After performing initial discography, CT discography is performed within 4 hours. It can be used in determining the status of the disc such as herniated, protruded, extruded, contained or sequestered. It can also be used in the spine to differentiate the mass effects of scar tissue or disc material after spinal surgery.

CT Myelography

This test is considered the best method for evaluating nerve root compression. When CT is performed in combination or after myelography, details about bony anatomy different planes can be obtained with relative ease.

Diagnostic Procedures

Transforaminal Selective Nerve Root Blocks (SNRBs)

When multilevel degenerative disc disease is suspected on an MRI scan, this test can be used to determine the specific nerve root that has been affected. SNRB is both a diagnostic and therapeutic test that can be used for lumbar spinal stenosis. The test creates a demotomal level area of hypoesthesia by injecting an anesthetic and a contrast material under fluoroscopic guidance to the interested nerve root level. There is a correlation between multilevel cervical degenerative disc disease clinical symptoms and findings on MRI and findings of SNRB according to Anderberg et al. There is a 28% correlation with SNRB results and with dermatomal radicular pain and areas of neurologic deficit. Most severe cases of degeneration on MRI are found to be correlated with 60%. Although not used routinely, SNRB is a useful test in evaluating patients before surgery in multilevel degenerative disc disease especially on the spine together with clinical features and findings on MRI. (Narouze, Samer, and Amaresh Vydyanathan)

Electro Myographic Studies

Distal motor and sensory nerve conduction tests, called electromyographic studies, that are normal with abnormal needle exam may reveal nerve compression symptoms that are elicited in the clinical history. Irritated nerve roots can be localized by using injections to anesthetize the affected nerves or pain receptors in the disc space, sacroiliac joint, or the facet joints by discography. (�Journal Of Electromyography & Kinesiology Calendar�)

Laboratory Studies

Laboratory tests are usually done to exclude other differential diagnoses.

As seronegative spondyloarthropathies, such as ankylosing spondylitis, are common causes of back pain, HLA B27 immuno-histocompatibility has to be tested. Estimated 350,000 persons in the US and 600,000 in Europe have been affected by this inflammatory disease of unknown etiology. But HLA B27 is extremely rarely found in African Americans. Other seronegative spondyloarthropathies that can be tested using this gene include psoriatic arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and reactive arthritis or Reiter syndrome. Serum immunoglobulin A (IgA) can be increased in some patients.

Tests like the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C- reactive protein (CRP) level test for the acute phase reactants seen in inflammatory causes of lower back pain such as osteoarthritis and malignancy. The full blood count is also required, including differential counts to ascertain the disease etiology. Autoimmune diseases are suspected when Rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) tests become positive. Serum uric acid and synovial fluid analysis for crystals may be needed in rare cases to exclude gout and pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition.

Treatment

There is no definitive treatment method agreed by all physicians regarding the treatment of degenerative disc disease because the cause of the pain can differ in different individuals and so is the severity of pain and the wide variations in clinical presentation. The treatment options can be discussed broadly under; conservative treatment, medical treatment, and surgical treatment.

Conservative Treatment

This treatment method includes exercise therapy with behavioral interventions, physical modalities, injections, back education, and back school methods.

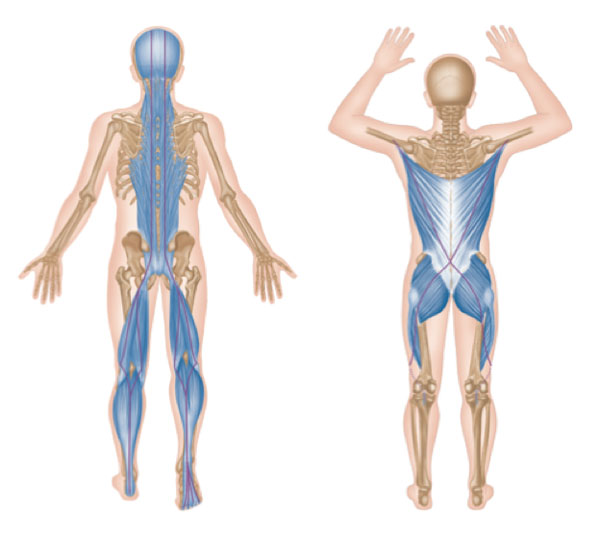

Exercise-Based Therapy with Behavioral Interventions

Depending on the diagnosis of the patient, different types of exercises can be prescribed. It is considered one of the main methods of conservative management to treat chronic low back pain. The exercises can be modified to include stretching exercises, aerobic exercises, and muscle strengthening exercises. One of the major challenges of this therapy includes its inability to assess the efficacy among patients due to wide variations in the exercise regimens, frequency, and intensity. According to studies, most effectiveness for sub-acute low back pain with varying duration of symptoms was obtained by performing graded exercise programs within the occupational setting of the patient. Significant improvements were observed among patients suffering from chronic symptoms with this therapy with regard to functional improvement and pain reduction. Individual therapies designed for each patient under close supervision and compliance of the patient also seems to be the most effective in chronic back pain sufferers. Other conservative approaches can be used in combination to improve this approach. (Hayden, Jill A., et al.)

Aerobic exercises, if performed regularly, can improve endurance. For relieving muscle tension, relaxation methods can be used. Swimming is also considered an exercise for back pain. Floor exercises can include extension exercises, hamstring stretches, low back stretches, double knee to chin stretches, seat lifts, modified sit-ups, abdominal bracing, and mountain and sag exercises.

Physical Modalities

This method includes the use of electrical nerve stimulation, relaxation, ice packs, biofeedback, heating pads, phonophoresis, and iontophoresis.

Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS)

In this non-invasive method, electrical stimulation is delivered to the skin in order to stimulate the peripheral nerves in the area to relieve the pain to some extent. This method relieves pain immediately following application but its long term effectiveness is doubtful. With some studies, it has been found that there is no significant improvement in pain and functional status when compared with placebo. The devices performing these TENS can be easily accessible from the outpatient department. The only side effect seems to be a mild skin irritation experienced in a third of patients. (Johnson, Mark I)

Back School

This method was introduced with the aim of reducing the pain symptoms and their recurrences. It was first introduced in Sweden and takes into account the posture, ergonomics, appropriate back exercises, and the anatomy of the lumbar region. Patients are taught the correct posture to sit, stand, lift weights, sleep, wash face, and brush teeth avoiding pain. When compared with other treatment modalities, back school therapy has been proven to be effective in both immediate and intermediate periods for improving back pain and functional status.

Patient Education

In this method, the provider instructs the patient on how to manage their back pain symptoms. Normal spinal anatomy and biomechanics involving mechanisms of injury is taught at first. Next, using the spinal models, the degenerative disc disease diagnosis is explained to the patient. For the individual patient, the balanced position is determined and then asked to maintain that position to avoid getting symptoms.

Bio-Psychosocial Approach to Multidisciplinary Back Therapy

Chronic back pain can cause a lot of distress to the patient, leading to psychological disturbances and low mood. This can adversely affect the therapeutic outcomes rendering most treatment strategies futile. Therefore, patients must be educated on learned cognitive strategies called �behavioral� and �bio-psychosocial� strategies to get relief from pain. In addition to treating the biological causes of pain, psychological, and social causes should also be addressed in this method. In order to reduce the patient�s perception of pain and disability, methods like modified expectations, relaxation techniques, control of physiological responses by learned behavior, and reinforcement are used.

Massage Therapy

For chronic low back pain, this therapy seems to be beneficial. Over a 1 year period, massage therapy has been found to be moderately effective for some patients when compared to acupuncture and other relaxation methods. However, it is less efficacious than TENS and exercise therapy although individual patients may prefer one over the other. (Furlan, Andrea D., et al.)

Spinal Manipulation

This therapy involves the manipulation of a joint beyond its normal range of movement, but not exceeding that of the normal anatomical range. This is a manual therapy that involves long lever manipulation with a low velocity. It is thought to improve low back pain through several mechanisms like the release of entrapped nerves, destruction of articular and peri-articular adhesions, and through manipulating segments of the spine that had undergone displacement. It can also reduce the bulging of the disc, relax the hypertonic muscles, stimulate the nociceptive fibers via changing the neurophysiological function and reposition the menisci on the articular surface.

Spinal manipulation is thought to be superior in efficacy when compared to most methods such as TENS, exercise therapy, NSAID drugs, and back school therapy. The currently available research is positive regarding its effectiveness in both the long and short term. It is also very safe to administer under-trained therapists with cases of disc herniation and cauda equina being reported only in lower than 1 in 3.7 million people. (Bronfort, Gert, et al.)

Lumbar Supports

Patients suffering from chronic low back pain due to degenerative processes at multiple levels with several causes may benefit from lumbar support. There is conflicting evidence with regards to its effectiveness with some studies claiming moderate improvement in immediate and long term relief while others suggesting no such improvement when compared to other treatment methods. Lumbar supports can stabilize, correct deformity, reduce mechanical forces, and limit the movements of the spine. It may also act as a placebo and reduce the pain by massaging the affected areas and applying heat.

Lumbar Traction

This method uses a harness attached to the iliac crest and lower rib cage and applies a longitudinal force along the axial spine to relieve chronic low back pain. The level and duration of the force are adjusted according to the patient and it can be measured by using devices both while walking and lying down. Lumbar traction acts by opening the intervertebral disc spaces and by reducing the lumbar lordosis. The symptoms of degenerative disc disease are reduced through this method due to temporary spine realignment and its associated benefits. It relieves nerve compression and mechanical stress, disrupts the adhesions in the facet and annulus, and also nociceptive pain signals. However, there is not much evidence with regard to its effectiveness in reducing back pain or improving daily function. Furthermore, the risks associated with lumbar traction are still under research and some case reports are available where it has caused a nerve impingement, respiratory difficulties, and blood pressure changes due to heavy force and incorrect placement of the harness. (Harte, A et al.)

Medical Treatment

Medical therapy involves drug treatment with muscle relaxants, steroid injections, NSAIDs, opioids, and other analgesics. This is needed, in addition to conservative treatment, in most patients with degenerative disc disease. Pharmacotherapy is aimed to control disability, reduce pain and swelling while improving the quality of life. It is catered according to the individual patient as there is no consensus regarding the treatment.

Muscle Relaxants

Degenerative disc disease may benefit from muscle relaxants by reducing the spasm of muscles and thereby relieving pain. The efficacy of muscle relaxants in improving pain and functional status has been established through several types of research. Benzodiazepine is the most common muscle relaxant currently in use.

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

These drugs are commonly used as the first step in disc degenerative disease providing analgesia, as well as anti-inflammatory effects. There is strong evidence that it reduces chronic low back pain. However, its use is limited by gastrointestinal disturbances, like acute gastritis. Selective COX2 inhibitors, like celecoxib, can overcome this problem by only targeting COX2 receptors. Their use is not widely accepted due to its potential side effects in increasing cardiovascular disease with prolonged use.

Opioid Medications

This is a step higher up in the WHO pain ladder. It is reserved for patients suffering from severe pain not responding to NSAIDs and those with unbearable GI disturbances with NSAID therapy. However, the prescription of narcotics for treating back pain varies considerably between clinicians. According to literature, 3 to 66% of patients may be taking some form of the opioid to relieve their back pain. Even though the short term reduction in symptoms is marked, there is a risk of long term narcotic abuse, a high rate of tolerance, and respiratory distress in the older population. Nausea and vomiting are some of the short term side effects encountered. (�Systematic Review: Opioid Treatment For Chronic Back Pain: Prevalence, Efficacy, And Association With Addiction�)

Anti-Depressants

Anti-depressants, in low doses, have analgesic value and may be beneficial in chronic low back pain patients who may present with associated depression symptoms. The pain and suffering may be disrupting the sleep of the patient and reducing the pain threshold. These can be addressed by using anti-depressants in low doses even though there is no evidence that it improves the function.

Injection Therapy

Epidural Steroid Injections

Epidural steroid injections are the most widely used injection type for the treatment of chronic degenerative disc disease and associated radiculopathy. There is a variation between the type of steroid used and its dose. 8- 10 mL of a mixture of methylprednisolone and normal saline is considered an effective and safe dose. The injections can be given through interlaminar, caudal, or trans foramina routes. A needle can be inserted under the guidance of fluoroscopy. First contrast, then local anesthesia and lastly, the steroid is injected into the epidural space at the affected level via this method. The pain relief is achieved due to the combination of effects from both local anesthesia and the steroid. Immediate pain relief can be achieved through the local anesthetic by blocking the pain signal transmission and while also confirming the diagnosis. Inflammation is also reduced due to the action of steroids in blocking pro-inflammatory cascade.

During the recent decade, the use of epidural steroid injection has increased by 121%. However, there is controversy regarding its use due to the variation in response levels and potentially serious adverse effects. Usually, these injections are believed to cause only short term relief of symptoms. Some clinicians may inject 2 to 3 injections within a one-week duration, although the long term results are the same for that of a patient given only a single injection. For a one year period, more than 4 injections shouldn�t be given. For more immediate and effective pain relief, preservative-free morphine can also be added to the injection. Even local anesthetics, like lidocaine and bupivacaine, are added for this purpose. Evidence for long term pain relief is limited. (�A Placebo-Controlled Trial To Evaluate Effectivity Of Pain Relief Using Ketamine With Epidural Steroids For Chronic Low Back Pain�)

There are potential side effects due to this therapy, in addition to its high cost and efficacy concerns. Needles can get misplaced if fluoroscopy is not used in as much as 25% of cases, even with the presence of experienced staff. The epidural placement can be identified by pruritus reliably. Respiratory depression or urinary retention can occur following injection with morphine and so the patient needs to be monitored for 24 hours following the injection.

Facet Injections

These injections are given to facet joints, also called zygapophysial joints, which are situated between two adjacent vertebrae. Anesthesia can be directly injected to the joint space or to the associated medial branch of the dorsal rami, which innervates it. There is evidence that this method improves the functional ability, quality of life, and relieves pain. They are thought to provide both short and long term benefits, although studies have shown both facet injections and epidural steroid injections are similar in efficacy. (Wynne, Kelly A)

SI Joint Injections

This is a diarthrodial synovial joint with nerve supply from both myelinated and non-myelin nerve axons. The injection can effectively treat degenerative disc disease involving sacroiliac joint leading to both long and short term relief from symptoms such as low back pain and referred pain at legs, thigh, and buttocks. The injections can be repeated every 2 to 3 months but should be performed only if clinically necessary. (MAUGARS, Y. et al.)�

Intradiscal Non-Operative Therapies for Discogenic Pain

As described under the investigations, discography can be used both as a diagnostic and therapeutic method. After the diseased disc is identified, several minimally invasive methods can be tried before embarking on surgery. Electrical current and its heat can be used to coagulate the posterior annulus thereby strengthening the collagen fibers, denaturing and destroying inflammatory mediators and nociceptors, and sealing figures. The methods used in this are called intradiscal electrothermal therapy (IDET) or radiofrequency posterior annuloplasty (RPA), in which an electrode is passed to the disc. IDET has moderate evidence in relief of symptoms for disc degenerative disease patients, while RPA has limited support regarding its short term and long term efficacy. Both these procedures can lead to complications such as nerve root injury, catheter malfunction, infection, and post-procedure disc herniation.

Surgical Treatment

Surgical treatment is reserved for patients with failed conservative therapy taking into account the disease severity, age, other comorbidities, socio-economic condition, and the level of outcome expected. It is estimated that around 5% of patients with degenerative disc disease undergo surgery, either for their lumbar disease or cervical disease. (Rydevik, Bj�rn L.)

Lumbar Spine Procedures

Lumbar surgery is indicated in patients with severe pain, with a duration of 6 to 12 months of ineffective drug therapy, who have critical spinal stenosis. The surgery is usually an elective procedure except in the case of cauda equina syndrome. There are two procedure types that aim to involve spinal fusion or decompression or both. (�Degenerative Disk Disease: Background, Anatomy, Pathophysiology.�)

Spinal fusion involves stopping movements at a painful vertebral segment in order to reduce the pain by fusing several vertebrae together by using a bone graft. It is considered effective in the long term for patients with degenerative disc disease having spinal malalignment or excessive movement. There are several approaches to fusion surgery. (Gupta, Vijay Kumar, et al)

- Lumbar spinal posterolateral guttur fusion

This method involves placing a bone graft in the posterolateral part of the spine. A bone graft can be harvested from the posterior iliac crest. The bones are stripped off from its periosteum for successful grafting. A back brace is needed in the post-operative period and patients may need to stay in the hospital for about 5 to 10 days. Limited motion and cessation of smoking are needed for successful fusion. However, several risks such as non-union, infection, bleeding, and solid union with back pain may occur.

- Posterior lumbar interbody fusion

In this method, decompression or diskectomy methods can also be performed via the same approach. The bone grafts are directly applied to the disc space and ligamentum flavum is excised completely. For the degenerative disc disease, interlaminar space is widened additionally by performing a partial medial facetectomy. Back braces are optional with this method. It has several disadvantages when compared to anterior approach such as only small grafts can be inserted, the reduced surface area available for fusion, and difficulty when performing surgery on spinal deformity patients. The major risk involved is non-union.

- Anterior lumbar interbody fusion

This procedure is similar to the posterior one except that it is approached through the abdomen instead of the back. It has the advantage of not disrupting the back muscles and the nerve supply. It is contraindicated in patients with osteoporosis and has the risk of bleeding, retrograde ejaculation in men, non-union, and infection.

- Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion

This is a modified version of the posterior approach which is becoming popular. It offers low risk with good exposure and it is shown to have an excellent outcome with a few complications such as CSF leak, transient neurological impairment, and wound infection.

Total Disc Arthroplasty

This is an alternative to disc fusion and it has been used to treat lumbar degenerative disc disease using an artificial disc to replace the affected disc. Total prosthesis or nuclear prosthesis can be used depending on the clinical situation.

Decompression involves removing part of the disc of the vertebral body, which is impinging on a nerve to release that and provide room for its recovery via procedures called diskectomy and laminectomy. The efficacy of the procedure is questionable although it is a commonly performed surgery. Complications are very few with a low chance of recurrence of symptoms with higher patient satisfaction. (Gupta, Vijay Kumar, et al)

The surgery is performed through a posterior midline approach by dividing the ligamentum flavum. The nerve root that is affected is identified and bulging annulus is cut to release it. Full neurological examination should be performed afterward and patients are usually fit to go home 1 � 5 days later. Low back exercises should be started soon followed by light work and then heavy work at 2 and 12 weeks respectively.

This procedure can be performed thorough one level, as well as through multiple levels. Laminectomy should be as short as possible to avoid spinal instability. Patients have marked relief of symptoms and reduction in radiculopathy following the procedure. The risks may include bowel and bladder incontinence, CSF leakage, nerve root damage, and infection.

Cervical Spine Procedures

Cervical degenerative disc disease is indicated for surgery when there is unbearable pain associated with progressive motor and sensory deficits. Surgery has a more than 90% favorable outcome when there is radiographic evidence of nerve root compression. There are several options including anterior cervical diskectomy (ACD), ACD, and fusion (ACDF), ACDF with internal fixation, and posterior foraminotomy. (�Degenerative Disk Disease: Background, Anatomy, Pathophysiology.�)

Cell-Based Therapy

Stem cell transplantation has emerged as a novel therapy for degenerative disc disease with promising results. The introduction of autologous chondrocytes has been found to reduce discogenic pain over a 2 year period. These therapies are currently undergoing human trials. (Jeong, Je Hoon, et al.)

Gene Therapy

Gene transduction in order to halt the disc degenerative process and even inducing disc regeneration is currently under research. For this, beneficial genes have to be identified while demoting the activity of degeneration promoting genes. These novel treatment options give hope for future treatment to be directed at regenerating intervertebral discs. (Nishida, Kotaro, et al.)

Degenerative disc disease is a health issue characterized by chronic back pain due to a damaged intervertebral disc, such as low back pain in the lumbar spine or neck pain in the cervical spine. It is a breakdown of an intervertebral disc of the spine. Several pathological changes can occur in disc degeneration. Various anatomical defects can also occur in the intervertebral disc. Low back pain and neck pain are major epidemiological problems, which are thought to be related to degenerative disc disease. Back pain is the second leading cause of doctor office visits in the United States. It is estimated that about 80% of US adults suffer from low back pain at least once during their lifetime. Therefore, a thorough understanding of degenerative disc disease is needed for managing this common condition. – Dr. Alex Jimenez D.C., C.C.S.T. Insight

The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal, physical medicines, wellness, and sensitive health issues and/or functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions. We use functional health & wellness protocols to treat and support care for injuries or disorders of the musculoskeletal system. Our posts, topics, subjects, and insights cover clinical matters, issues, and topics that relate and support directly or indirectly our clinical scope of practice.* Our office has made a reasonable attempt to provide supportive citations and has identified the relevant research study or studies supporting our posts. We also make copies of supporting research studies available to the board and or the public upon request. We understand that we cover matters that require an additional explanation as to how it may assist in a particular care plan or treatment protocol; therefore, to further discuss the subject matter above, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900. The provider(s) Licensed in Texas*& New Mexico*�

Curated by Dr. Alex Jimenez D.C., C.C.S.T.

References

- �Degenerative Disc Disease.� Spine-Health, 2017, https://www.spine-health.com/glossary/degenerative-disc-disease.

- Modic, Michael T., and Jeffrey S. Ross. �Lumbar Degenerative Disk Disease.� Radiology, vol 245, no. 1, 2007, pp. 43-61. Radiological Society Of North America (RSNA), doi:10.1148/radiol.2451051706.

- �Degenerative Disk Disease: Background, Anatomy, Pathophysiology.� Emedicine.Medscape.Com, 2017, http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1265453-overview.

- Taher, Fadi et al. �Lumbar Degenerative Disc Disease: Current And Future Concepts Of Diagnosis And Management.� Advances In Orthopedics, vol 2012, 2012, pp. 1-7. Hindawi Limited, doi:10.1155/2012/970752.

- Choi, Yong-Soo. �Pathophysiology Of Degenerative Disc Disease.� Asian Spine Journal, vol 3, no. 1, 2009, p. 39. Korean Society Of Spine Surgery (KAMJE), doi:10.4184/asj.2009.3.1.39.

- Wheater, Paul R et al. Wheater�s Functional Histology. 5th ed., [New Delhi], Churchill Livingstone, 2007,.

- Palmgren, Tove et al. �An Immunohistochemical Study Of Nerve Structures In The Anulus Fibrosus Of Human Normal Lumbar Intervertebral Discs.� Spine, vol 24, no. 20, 1999, p. 2075. Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health), doi:10.1097/00007632-199910150-00002.

- BOGDUK, NIKOLAI et al. �The Innervation Of The Cervical Intervertebral Discs.� Spine, vol 13, no. 1, 1988, pp. 2-8. Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health), doi:10.1097/00007632-198801000-00002.

- �Intervertebral Disc � Spine � Orthobullets.Com.� Orthobullets.Com, 2017, https://www.orthobullets.com/spine/9020/intervertebral-disc.

- Suthar, Pokhraj. �MRI Evaluation Of Lumbar Disc Degenerative Disease.� JOURNAL OF CLINICAL AND DIAGNOSTIC RESEARCH, 2015, JCDR Research And Publications, doi:10.7860/jcdr/2015/11927.5761.

- Buckwalter, Joseph A. �Aging And Degeneration Of The Human Intervertebral Disc.� Spine, vol 20, no. 11, 1995, pp. 1307-1314. Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health), doi:10.1097/00007632-199506000-00022.

- Roberts, S. et al. �Senescence In Human Intervertebral Discs.� European Spine Journal, vol 15, no. S3, 2006, pp. 312-316. Springer Nature, doi:10.1007/s00586-006-0126-8.

- Boyd, Lawrence M. et al. �Early-Onset Degeneration Of The Intervertebral Disc And Vertebral End Plate In Mice Deficient In Type IX Collagen.� Arthritis & Rheumatism, vol 58, no. 1, 2007, pp. 164-171. Wiley-Blackwell, doi:10.1002/art.23231.

- Williams, F.M.K., and P.N. Sambrook. �Neck And Back Pain And Intervertebral Disc Degeneration: Role Of Occupational Factors.� Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology, vol 25, no. 1, 2011, pp. 69-79. Elsevier BV, doi:10.1016/j.berh.2011.01.007.

- Batti�, Michele C. �Lumbar Disc Degeneration: Epidemiology And Genetics.� The Journal Of Bone And Joint Surgery (American), vol 88, no. suppl_2, 2006, p. 3. Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health), doi:10.2106/jbjs.e.01313.

- BATTI�, MICHELE C. et al. �1991 Volvo Award In Clinical Sciences.� Spine, vol 16, no. 9, 1991, pp. 1015-1021. Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health), doi:10.1097/00007632-199109000-00001.

- Kauppila, L.I. �Atherosclerosis And Disc Degeneration/Low-Back Pain � A Systematic Review.� Journal Of Vascular Surgery, vol 49, no. 6, 2009, p. 1629. Elsevier BV, doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2009.04.030.

- �A Population-Based Study Of Juvenile Disc Degeneration And Its Association With Overweight And Obesity, Low Back Pain, And Diminished Functional Status. Samartzis D, Karppinen J, Mok F, Fong DY, Luk KD, Cheung KM. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011;93(7):662�70.� The Spine Journal, vol 11, no. 7, 2011, p. 677. Elsevier BV, doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2011.07.008.

- Gupta, Vijay Kumar et al. �Lumbar Degenerative Disc Disease: Clinical Presentation And Treatment Approaches.� IOSR Journal Of Dental And Medical Sciences, vol 15, no. 08, 2016, pp. 12-23. IOSR Journals, doi:10.9790/0853-1508051223.

- Bhatnagar, Sushma, and Maynak Gupta. �Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines For Interventional Pain Management In Cancer Pain.� Indian Journal Of Palliative Care, vol 21, no. 2, 2015, p. 137. Medknow, doi:10.4103/0973-1075.156466.

- KIRKALDY-WILLIS, W H et al. �Pathology And Pathogenesis Of Lumbar Spondylosis And Stenosis.� Spine, vol 3, no. 4, 1978, pp. 319-328. Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health), doi:10.1097/00007632-197812000-00004.

- KONTTINEN, YRJ� T. et al. �Neuroimmunohistochemical Analysis Of Peridiscal Nociceptive Neural Elements.� Spine, vol 15, no. 5, 1990, pp. 383-386. Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health), doi:10.1097/00007632-199005000-00008.

- Brisby, Helena. �Pathology And Possible Mechanisms Of Nervous System Response To Disc Degeneration.� The Journal Of Bone And Joint Surgery (American), vol 88, no. suppl_2, 2006, p. 68. Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health), doi:10.2106/jbjs.e.01282.

- Jason M. Highsmith, MD. �Degenerative Disc Disease Symptoms | Back Pain, Leg Pain.� Spineuniverse, 2017, https://www.spineuniverse.com/conditions/degenerative-disc/symptoms-degenerative-disc-disease.

- �Degenerative Disc Disease � Physiopedia.� Physio-Pedia.Com, 2017, https://www.physio-pedia.com/Degenerative_Disc_Disease.

- Modic, M T et al. �Degenerative Disk Disease: Assessment Of Changes In Vertebral Body Marrow With MR Imaging..� Radiology, vol 166, no. 1, 1988, pp. 193-199. Radiological Society Of North America (RSNA), doi:10.1148/radiology.166.1.3336678.

- Pfirrmann, Christian W. A. et al. �Magnetic Resonance Classification Of Lumbar Intervertebral Disc Degeneration.� Spine, vol 26, no. 17, 2001, pp. 1873-1878. Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health), doi:10.1097/00007632-200109010-00011.

- Bartynski, Walter S., and A. Orlando Ortiz. �Interventional Assessment Of The Lumbar Disk: Provocation Lumbar Diskography And Functional Anesthetic Diskography.� Techniques In Vascular And Interventional Radiology, vol 12, no. 1, 2009, pp. 33-43. Elsevier BV, doi:10.1053/j.tvir.2009.06.003.

- Narouze, Samer, and Amaresh Vydyanathan. �Ultrasound-Guided Cervical Transforaminal Injection And Selective Nerve Root Block.� Techniques In Regional Anesthesia And Pain Management, vol 13, no. 3, 2009, pp. 137-141. Elsevier BV, doi:10.1053/j.trap.2009.06.016.

- �Journal Of Electromyography & Kinesiology Calendar.� Journal Of Electromyography And Kinesiology, vol 4, no. 2, 1994, p. 126. Elsevier BV, doi:10.1016/1050-6411(94)90034-5.

- Hayden, Jill A. et al. �Systematic Review: Strategies For Using Exercise Therapy To Improve Outcomes In Chronic Low Back Pain.� Annals Of Internal Medicine, vol 142, no. 9, 2005, p. 776. American College Of Physicians, doi:10.7326/0003-4819-142-9-200505030-00014.

- Johnson, Mark I. �Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) And TENS-Like Devices: Do They Provide Pain Relief?.� Pain Reviews, vol 8, no. 3-4, 2001, pp. 121-158. Portico, doi:10.1191/0968130201pr182ra.

- Harte, A et al. �Efficacy Of Lumbar Traction In The Management Of Low Back Pain.� Physiotherapy, vol 88, no. 7, 2002, pp. 433-434. Elsevier BV, doi:10.1016/s0031-9406(05)61278-3.

- Bronfort, Gert et al. �Efficacy Of Spinal Manipulation And Mobilization For Low Back Pain And Neck Pain: A Systematic Review And Best Evidence Synthesis.� The Spine Journal, vol 4, no. 3, 2004, pp. 335-356. Elsevier BV, doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2003.06.002.

- Furlan, Andrea D. et al. �Massage For Low-Back Pain: A Systematic Review Within The Framework Of The Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group.� Spine, vol 27, no. 17, 2002, pp. 1896-1910. Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health), doi:10.1097/00007632-200209010-00017.

- �Systematic Review: Opioid Treatment For Chronic Back Pain: Prevalence, Efficacy, And Association With Addiction.� Clinical Governance: An International Journal, vol 12, no. 4, 2007, Emerald, doi:10.1108/cgij.2007.24812dae.007.

- �A Placebo Controlled Trial To Evaluate Effectivity Of Pain Relief Using Ketamine With Epidural Steroids For Chronic Low Back Pain.� International Journal Of Science And Research (IJSR), vol 5, no. 2, 2016, pp. 546-548. International Journal Of Science And Research, doi:10.21275/v5i2.nov161215.

- Wynne, Kelly A. �Facet Joint Injections In The Management Of Chronic Low Back Pain: A Review.� Pain Reviews, vol 9, no. 2, 2002, pp. 81-86. Portico, doi:10.1191/0968130202pr190ra.

- MAUGARS, Y. et al. �ASSESSMENT OF THE EFFICACY OF SACROILIAC CORTICOSTEROID INJECTIONS IN SPONDYLARTHROPATHIES: A DOUBLE-BLIND STUDY.� Rheumatology, vol 35, no. 8, 1996, pp. 767-770. Oxford University Press (OUP), doi:10.1093/rheumatology/35.8.767.

- Rydevik, Bj�rn L. �Point Of View: Seven- To 10-Year Outcome Of Decompressive Surgery For Degenerative Lumbar Spinal Stenosis.� Spine, vol 21, no. 1, 1996, p. 98. Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health), doi:10.1097/00007632-199601010-00023.

- Jeong, Je Hoon et al. �Regeneration Of Intervertebral Discs In A Rat Disc Degeneration Model By Implanted Adipose-Tissue-Derived Stromal Cells.� Acta Neurochirurgica, vol 152, no. 10, 2010, pp. 1771-1777. Springer Nature, doi:10.1007/s00701-010-0698-2.

- Nishida, Kotaro et al. �Gene Therapy Approach For Disc Degeneration And Associated Spinal Disorders.� European Spine Journal, vol 17, no. S4, 2008, pp. 459-466. Springer Nature, doi:10.1007/s00586-008-0751-5.