Migraine Education Improves Headache Treatment in El Paso, TX

Migraine symptoms are painful and debilitating, often affecting the quality of life of many migraine sufferers around the globe. Although headache pain is one of the most prevalent reasons for doctor office visits each year, migraines are considered to be one of the most underdiagnosed and undertreated diseases in the medical field. Furthermore, the emotional distress caused by the unresolved physical symptoms of migraines can create a number of mental health issues which can lead to worsened symptoms.�As a result, migraine education efforts have been implemented as a part of many headache treatment options, including chiropractic care. The purpose of the following article is to demonstrate the benefits of a primary care migraine education program, known as the Mercy Migraine Management Program or MMMP, on headache impact and quality of life.

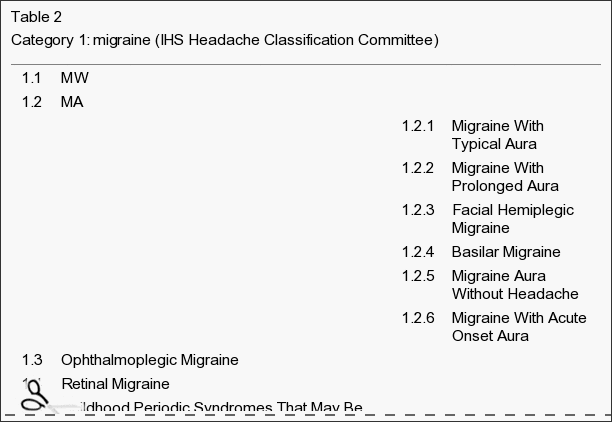

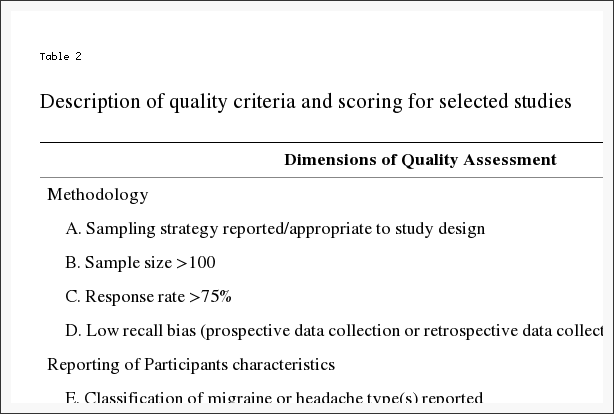

A Primary Care Migraine Education Program has Benefit on Headache Impact and Quality of Life: Results from the Mercy Migraine Management Program

Abstract

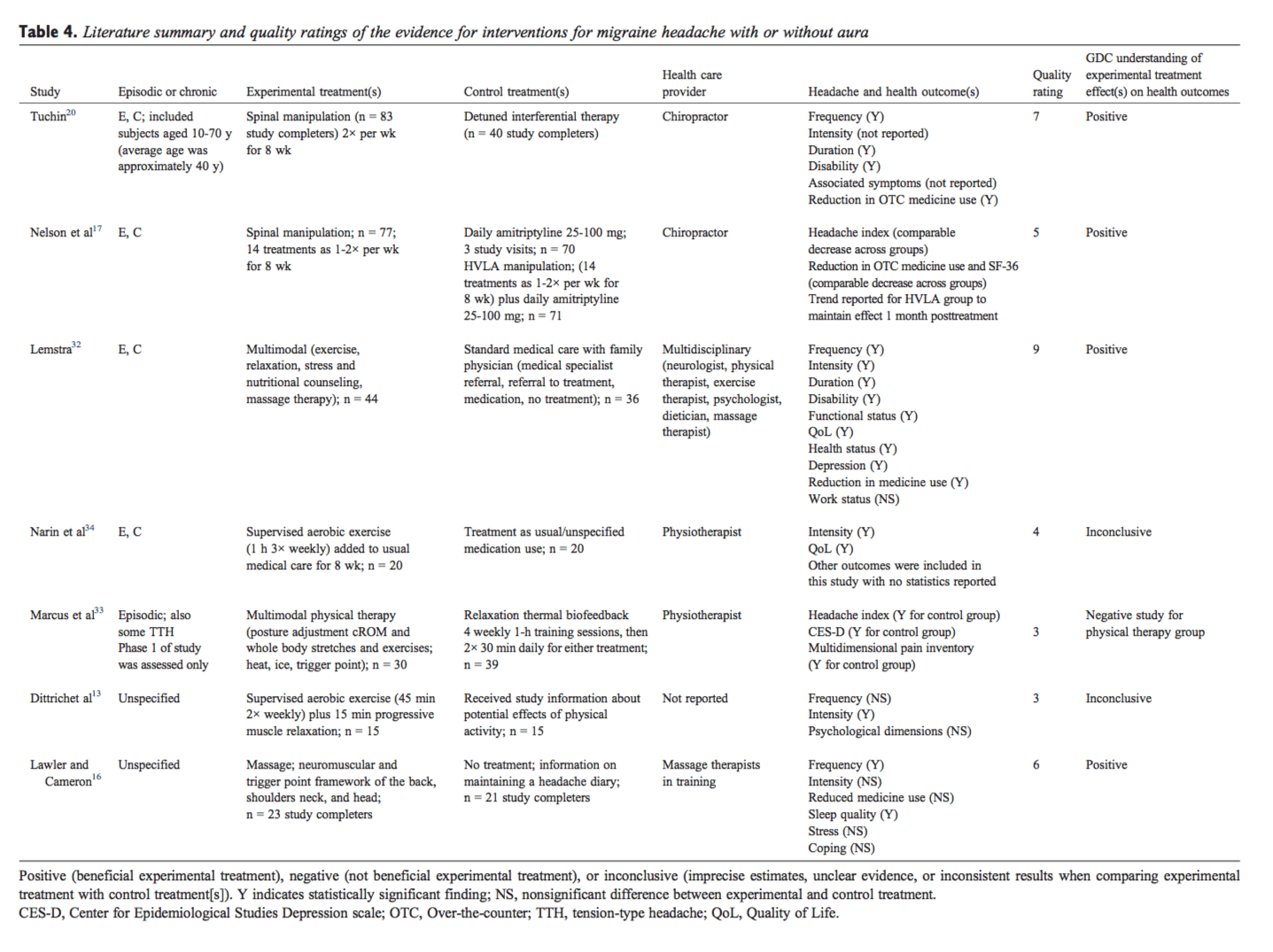

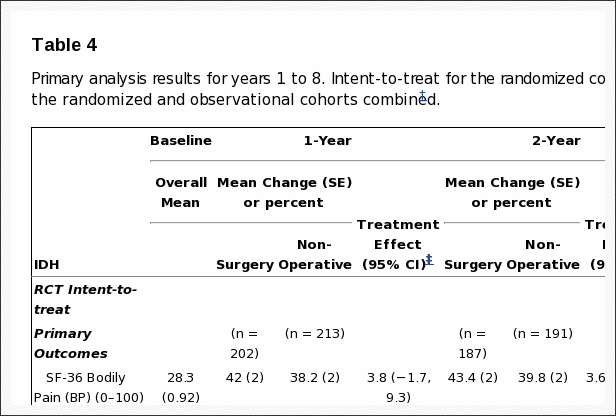

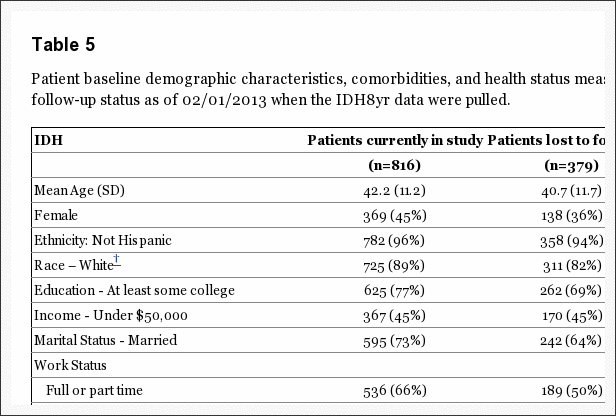

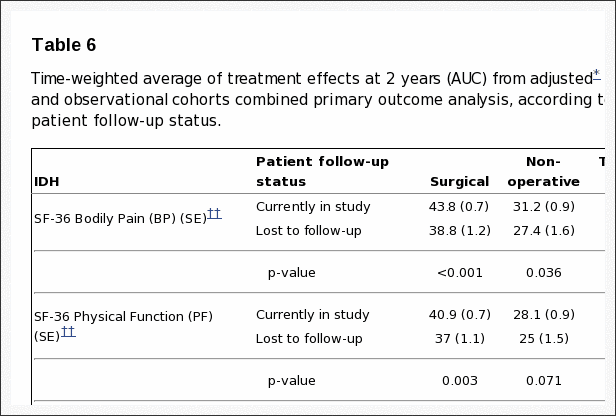

- Objective: The objective of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of the Mercy Migraine Management Program (MMMP), an educational program for physicians and patients. The primary outcome was change in headache days from baseline at 3, 6, and 12 months. Secondary outcomes were changes in migraine-related disability and quality of life, worry about headaches, self-efficacy for managing migraines, ER visits for headache, and satisfaction with headache care.

- Background: Despite progress in the understanding of the pathophysiology of migraine and development of effective therapeutic agents, many practitioners and patients continue to lack the knowledge and skills to effectively manage migraine. Educational efforts have been helpful in improving the quality of care and quality of life for migraine sufferers. However, little work has been done to evaluate these changes over a longer period of time. Also, there is a paucity of published research evaluating the influence of education about migraine management on cognitive and emotional factors (e.g., self-efficacy for managing headaches, worry about headaches).

- Methods: In this open-label, prospective study, 284 individuals with migraine (92% female, mean age = 41.6) participated in the MMMP, an educational and skills based program. Of the 284 who participated in the program, 228 (80%) provided data about their headache frequency, headache-related disability (as measured by the Headache Impact Test-6 (HIT-6), migraine-specific quality of life (MSQ), worry about headaches, self-efficacy for managing headaches, ER visits for headaches, and satisfaction with care at four time points over 12 months (baseline, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months).

- Results: Overall, 46% (106) of subjects reported a 50% or greater reduction in headache frequency. Over 12 months, patients reported fewer headaches and improvement on the HIT-6 and MSQ (all p < .001). The improvement in headache impact and quality of life was greater among those who had more worry about their headaches at baseline. There were also significant improvements in �worry about headaches�, �self-efficacy for managing headaches�, and �satisfaction with headache care�.

- Conclusion: The findings demonstrate that patients participating in the MMMP reported improvements in their headache frequency as well as the cognitive and emotional aspects of headache management. This program was especially helpful among those with high amounts of worry about their headaches at the beginning of the program. The findings from this study are impetus for further research that will more clearly, through evaluate the effects of education and skill development not only on headache but also emotional and cognitive influences.

Dr. Alex Jimenez’s Insight

Migraine headache pain is characterized as a disabling symptom which can tremendously impact an individual’s quality of life. Plus, the stress created by the worry of an imminent migraine can result in a variety of mental health issues. Many healthcare professionals and migraine sufferers lack the proper knowledge and skills on how to effectively manage migraine symptoms. Fortunately, migraine education programs, like the Mercy Migraine Management Program (MMMP), were designed to teach patients how to improve their quality of care and quality of life. Migraine education programs such as these have been demonstrated to especially benefit migraineurs with higher levels of stress. Aside from providing spinal adjustments and manual manipulations to correct the alignment of the spine, chiropractic care focuses on the treatment of the body as a whole, making sure patients are educated regarding their migraine symptoms.

Introduction

Migraine headache is a highly prevalent, painful, disabling and costly disease. The evaluation, treatment and management of migraine have been estimated to involve 5 to 9 million office visits per year to primary care physicians in the United States.[1,2] Migraine is one of the most common reason for an outpatient office visit.[3] Numerous studies have reported that patients with migraines have significantly higher pharmacy and medical claims than those without migraine.[4�7] Migraine also has high indirect costs; it has been estimated to cost US employers between 17 and 20 billion dollars annually in lost work productivity.[8,9]

Despite its prevalence and high cost, migraine remains an underdiagnosed and undertreated disease.[10�14] Given the availability of migraine-specific therapeutic agents, it is vital that physicians be able to accurately diagnose migraine. Moreover, it is important for physicians to recognize the benefits of treating migraine as a specific condition as opposed to simply �head pain�. Unfortunately recent findings concerning the accurate diagnosis and treatment of migraine suggest that most patients with migraine are not accurately diagnosed or treated.[10�12,14]

Migraine is currently conceptualized as a chronic neurologic disease characterized by intermittent episodes of acute pain.[15�17] Current guidelines for managing chronic diseases emphasize the importance of self-management.[18�22] In self-management, the emphasis is on both the patient and the provider actively treating the disease, with the patient managing the disease outside the clinical setting. Self-management (or self-care) requires that the provider afford the patient the opportunity to take the right dose of the right medication at the right time, is educated about migraine and its management, and is equipped with tools to minimize the frequency and deleterious effects of migraine attacks.

Most migraine sufferers experience some disability from headache pain and the associated symptoms of migraine.[23�26] It is often the disability emanating from migraine attacks that compromises quality of life, thus making migraine both a pain problem and a life problem. For many patients, recurrent disability combined with a lack of effective coping tools and medications that are not always effective can create uneasiness, worry and anxiety between attacks as well as when an impending attack seems imminent. This worry and anxiety may be related to low self-efficacy, a cognitive variable that involves an individual�s belief that she or he is able to successfully manage a situation.[27�29] Self-efficacy has been theorized as a potent influence of how well one manages migraines.[29�33] Recent development of new therapeutic agents and the advent of improved educational efforts have been helpful in validating migraine and improving the quality of care for migraine sufferers. However, demonstrating the overall value of a primary care based educational program for migraine is difficult. Previously published articles evaluating the benefits of migraine education have reported successful results.[34�39] However, these programs mainly involved referral of patients into a specialized clinic or educational facility for instruction from specialist practitioners or educators and followed outcomes of the patients after enrollment. Unfortunately, few communities have access to such headache specialty clinics. Accordingly, most patients rely on their primary care clinicians for educational content and counseling regarding headache care. With these concepts in mind, the Mercy Migraine Management Program (MMMP), a multi-center, targeted enrollment study was undertaken to demonstrate the overall value of a migraine educational program through a provider-group setting. Given the paucity of programs whereby the physicians and participants are provided a one-time educational program, the decision was made to evaluate whether a program of this nature was feasible and suggestive of efficacy. If so, then this would allow for further investigation using a more elegant design.

The current study was an open trial looking at the effects of the MMMP. The effect of participation in the educational program on headache frequency, headache-related quality of life, headache-related worry, self-efficacy, treatment satisfaction, and emergency room visits for headache was assessed.

Methods

Participants

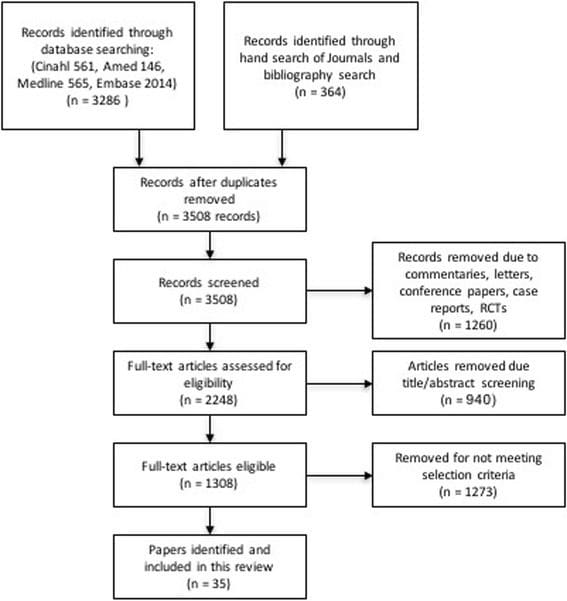

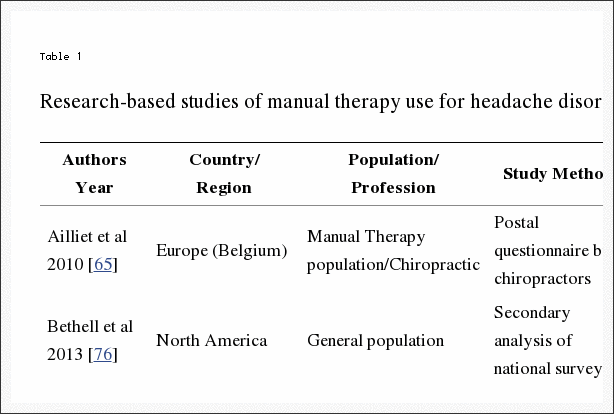

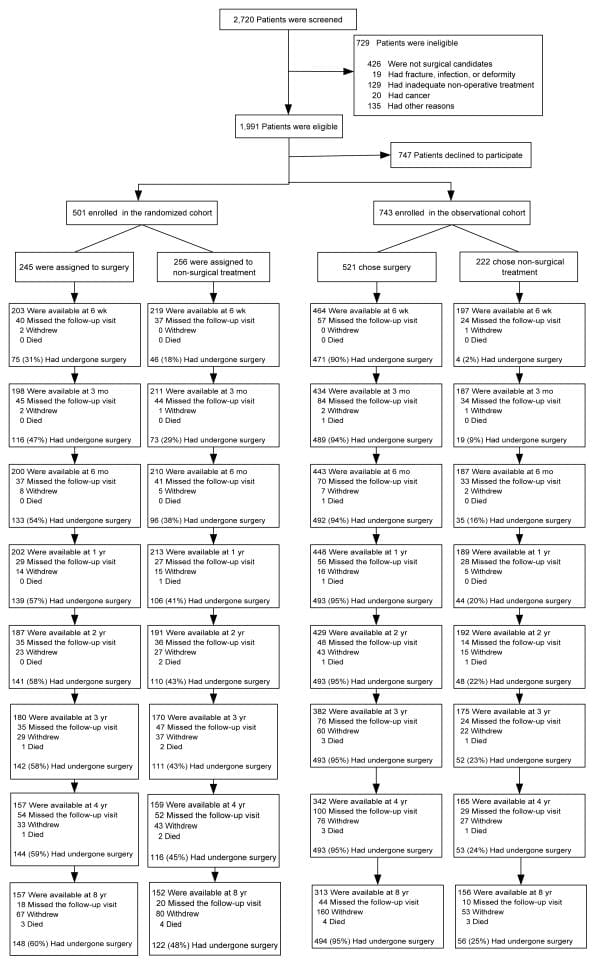

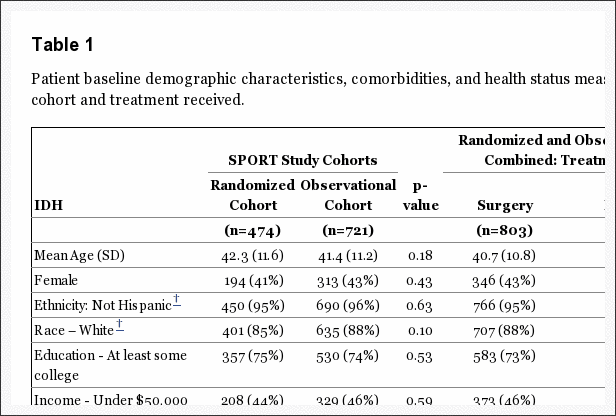

The research was conducted within a 120-clinician primary care group practice caring for more than 200,000 patients (St. Johns Mercy Medical Group in St. Louis, Missouri). A total of 31 physicians and three nurse practitioners from 14 of the group�s practice sites agreed to participate. From these sites, a total of 284 patients with migraine were identified and recruited by the clinicians and agreed to participate. Among participants 92% (n = 260) were female and the mean age was 42 (SD = 12.45). In order to be eligible, patients were required to have one or more of the following: (a) ICD-9-CM code for migraine/headache diagnosis in the previous six months; (b) one or more claims for acute migraine/headache medications in the previous six months; or (c) patients with one or more ER or urgent care center visits in the previous six months coded for migraine/headache or headache NOS and at least one migraine medication. In addition, patients who presented to the primary care office for evaluation of headache were eligible for enrollment in the program if they were given an ICD-9-CM code for migraine/headache diagnosis at that time.

Procedures

Provider Education and Training

Clinicians who expressed interest in participating attended a two-hour continuing medical education program on migraine. The program covered four key concepts: (1) impact recognition diagnosis of headache (office recognition of migraine based on headache repercussions and disability rather than the characteristics of pain alone), (2) the benefits of early abortive intervention, especially with migraine-specific medications, (3) effective preventive regimens, and (4) non-pharmacologic management. The overarching goal of the program was to educate providers about how to equip the patient with tools they can use to manage their migraines on a daily basis. Participating clinicians and their staff were provided printed educational materials. A majority of the materials were developed or selected for use by the first author. These were supplemented by standardized educational materials which included: (a) Patient Centered Strategies for Effective Management of Migraine[40]; (b) The Migraineur�s Guide to Migraine[41]; and (c) Provider and Patient Tipsheets from the Migraine Matrix� education program[41], a comprehensive migraine management program for providers.

Following their participation in the educational session, physicians from the practice sites sent IRB approved notices to potentially eligible patients, identified from claims data, informing them of the study or spoke with them directly during routine office visits for headache treatment. Interested individuals who responded to the mailed invitations then came to the practice site where their migraine diagnoses were confirmed and informed consent for participation was provided, as approved by the local IRB. The subjects subsequently completed study related questionnaires. Subjects recruited at the time of an office encounter were invited to participate at the time of said visit, provided informed consent in like-manner to those described above, and completed the baseline questonnaire.

After the questionnaires were completed, the clinician provided medication or other treatment recommendations based on their knowledge attained from the educational seminar and print materials previously provided to them. No mandatory interventions were required on the part of the provider. They were to make medication and other management decisions as they saw fit for each individual participant according to their own knowledge, understanding, and preferences. They were however required to provide the educational information from the study to the individual subjects enrolled in the trial. The clinician or a member of the health care team provided the patient with the educational materials and instructed them on how to use them. The patients were encouraged to use the materials as best fit their individual situation. The materials were designed to give the patient tools to self-manage their migraines in conjunction with ongoing care from their health care team. These materials included: (a) The Migraineur�s Guide to Migraine[41]; (b) a headache diary; (c) Patient Tipsheets from the Migraine Matrix� education program[42]; (d) educational materials on diet recommendations from the National Headache Foundation; (e) written and visual instruction on how to do cervical range of motion and stretching exercises from the physical therapy department that is associated with the St John�s Mercy Medical Group; (f) biofeedback tapes developed by the Primary Care Network; and (g) Managing Your Migraine Headaches.

The patients took the materials home with instructions to be as consistent as possible with adherence to the concepts proscribed by the educational packet. After 3-months, assessments were mailed to the participants with a self-addressed stamped envelope to return. The same assessments were mailed at 6-months and 12-months post-baseline as well.

Measures

The measures below were self-administered at baseline, 3-months, 6-months, and 12-months post-baseline.

Headache Days. Individuals reported the number of days they experienced headaches over the previous 90 days. This was a primary outcome of interest.

Disability/Quality of Life

Headache Impact Test-6 (HIT-6). The HIT-6 is a six-item measure that is a reliable and valid measure assessing the impact of headache on patients� lives.[43�44] Scores for the HIT-6 are derived by summing the responses to all the items. Higher scores reflect higher levels of headache impact (i.e., poorer quality of life). This was a primary outcome of interest.

Migraine Specific Quality of life (MSQ). The MSQ is a 14-item measure designed to assess the effects of migraine on an individual�s quality of life.[45�46] There are three MSQ subscales, Emotional (MSQ-E), restrictive (MSQ-R), and preventive (MSQ-P). The MSQ has been shown to be an internally consistent, valid measure. The MSQ was not done at 3 months. This was a primary outcome of interest.

Worry about headaches. Individuals indicated the extent to which they worried about headaches disrupting their life using a 4-point scale with options of �rarely�, �sometimes�, �often�, and �almost always�. For purposes of the current study, dichotomous groups were created. Individuals who answered �rarely� or �sometimes� were labeled Low Worry. Those who answered �often� or �almost always� were labeled High Worry.

Self-efficacy for controlling headaches. Individuals indicated the extent to which they were confident in their ability to do things to help control their headaches using a 4-point scale with options of �not confident�, �a little confident�, �fairly confident�, and �very confident�. Individuals who answered �not confident� or �a little confident� were labeled Low Self-Efficacy. Those who answered �fairly confident� or �very confident� were labeled High Self-Efficacy.

Satisfaction with headache care. Individuals indicated (Yes/No) whether they were satisfied with the headache care they were receiving.

ER visits. Individuals indicated the number of times they had been to the ER for headaches during the previous 3 months. For purposes of the current study a dichotomous yes/no variable was created in order to create a percentage of individuals who had visited the ER during the previous 90 days.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were conducted using SPSS v. 15.[47] Prior to analysis, data were checked for the fit between scale distribution and the assumptions of normality. Headache frequency violated normality assumptions and was transformed (although the transformed variables were used in the model, the original data is used in the figures for ease of understanding for the reader).

A linear random mixed model (treating subjects as random effects) was used to model the change in headache frequency at the four time points over 12 months (baseline, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months). The same was done for the HIT-6 (measured at baseline, 3-months, 6-months and 12-months) and the MSQ subscales (measured at baseline, 6-months and 12-months). In order to determine whether baseline worry and confidence influenced changes in headache and quality of life, these variables were included in the models. Although the potential existed to investigate 3-way interactions (time � worry � confidence), doing so created cells with extremely low n and thus 2-way interactions were the higher order interactions analyzed. For all comparisons, Bonferroni adjustments were made.

In order to evaluate whether there were significant changes over time for worry, efficacy, patient�s satisfaction with their headache care, or ER visits, McNemar�s test was conducted. To account for multiple comparisons, the significance level for each set of comparisons was adjusted to p<.008.

The protocol and procedures for this study were approved by the local Institutional Review Board.

Results

Headache Frequency Change Over Time

Results indicated that overall, at 3 months, 34% (n = 77/228) reported at least a 50% reduction in headache frequency from baseline. This increased to 38% (N=86) at 6 months and 46% (N=106) at 12 months.

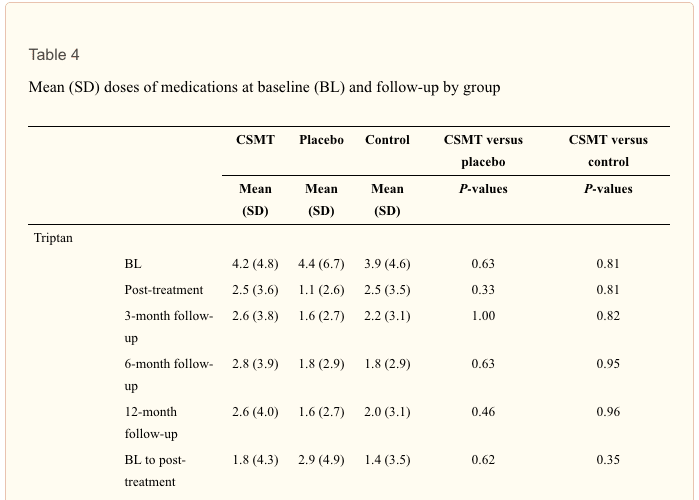

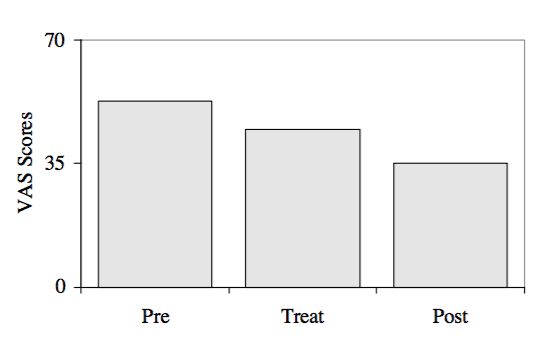

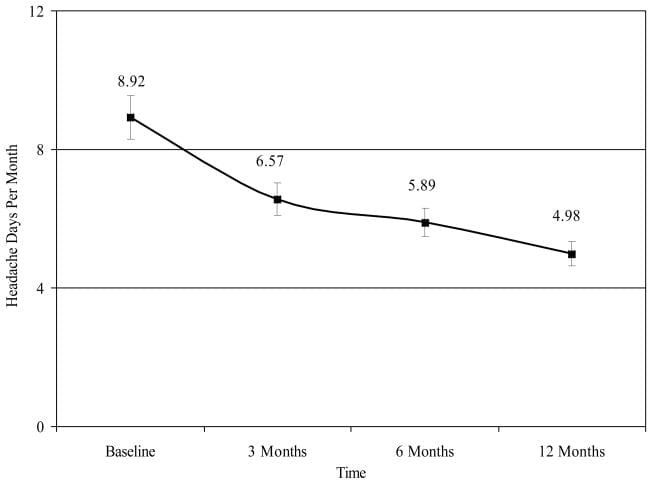

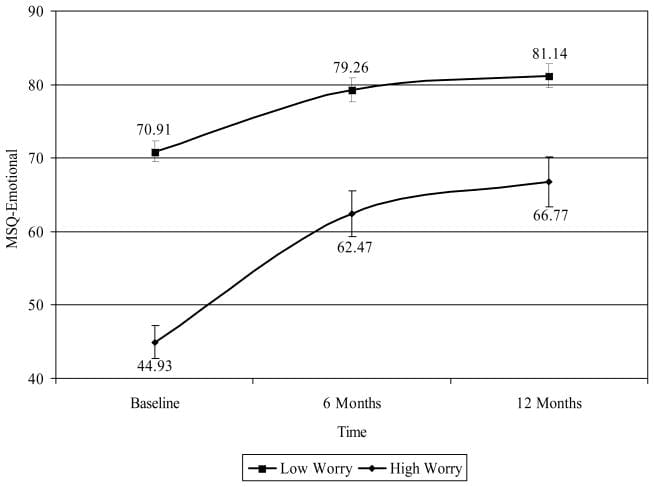

Results indicated that the main effect for reduction in headache frequency was significant (F [3, 691] = 27.89, p < .001). Figure 1 shows headache frequency per month at each time point. Table 1 shows that there was a significant reduction in headache frequency from baseline to each subsequent time point (p < .001). Also, headache frequency at month 12 was significantly lower than at month 3 and 6 (p<.001). The main effect for worry was also significant (F [1, 308] = 12.03, p < .001). Those who were labeled as having High Worry had significantly more headaches (M = 8.00, SE = .63) across the time frames than did those who were labeled as having Low Worry (M = 5.89, SE = .46) (95% CID = .62�3.68). The main effect for confidence, the time X worry interaction, and the time X confidence were all non-significant.

Figure 1: Headache days per month at baseline, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months.

Quality of Life Disability

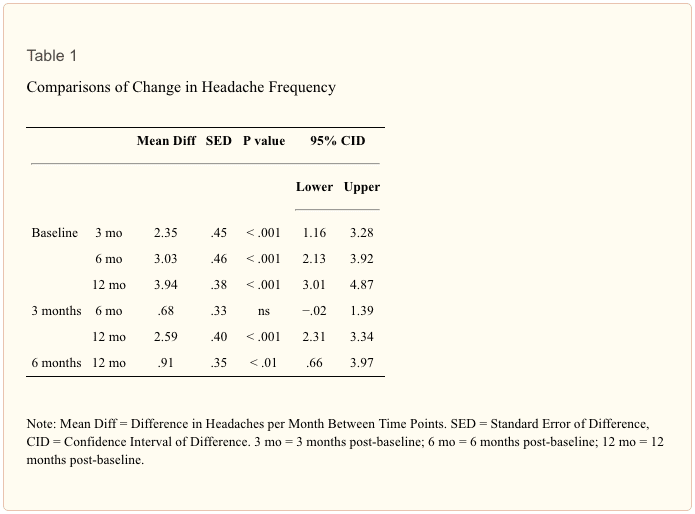

HIT-6. Results indicate that the time X worry interaction was significant (F [2, 464] = 4.54, p < .01). Figure 2 shows HIT-6 scores for each time point by level of worry. Simple effects analysis showed that the degree of reduction in headache impact was greater at 3 months among those with High Worry than among those with Low Worry. Also, those with Low Worry showed a significant reduction in headache impact comparing baseline to 3 months and 6 months, and from 3 months to 6 months, whereas those with High Worry had a significant reduction in headache impact from baseline to 3 months but not from 3 months 6 months. The main effect for confidence was significant (F [1, 292] = 4.54, p < .001) such that those with High Self-Efficacy (M = 59.60, SE = .52) had less headache impact than those with Low Self-Efficacy (M = 61.72, SD = .70) (CID = .79�3.45). Neither the time X self-efficacy or worry X self-efficacy interaction was not significant.

Figure 2: HIT-6 at each time point by worry.

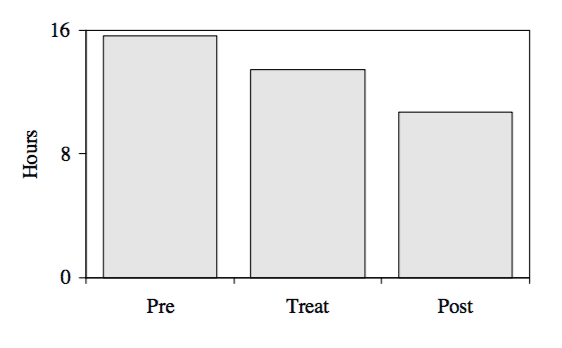

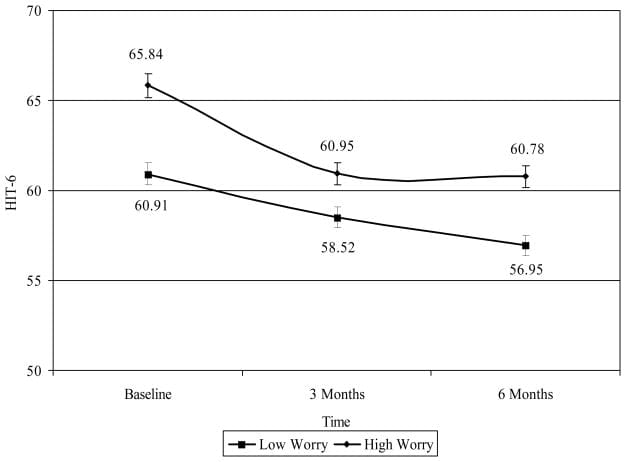

MSQ-E. Results indicate that the time X worry interaction was significant (F [2, 468] = 5.18, p < .01). Figure 3 shows MSQ-E scores for each time point by level of worry. Simple effects analysis showed that the degree of improvement in MSQ-E was greater at 3 months among those with High Worry than among those with Low Worry. The main effect for confidence was significant (F [1, 292] = 4.54, p < .001) such that those with High Self-Efficacy (M = 59.60, SD = 1.74) had better quality of life than those with Low Self-Efficacy (M = 61.72, SD = 1.87) (CID = .79�3.45). The main effect for self-efficacy, the time X self-efficacy interaction, and the worry X self-efficacy interaction were not significant.

Figure 3: MSQ-E at each time point by worry.

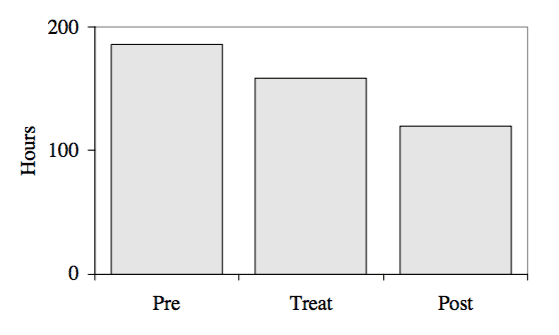

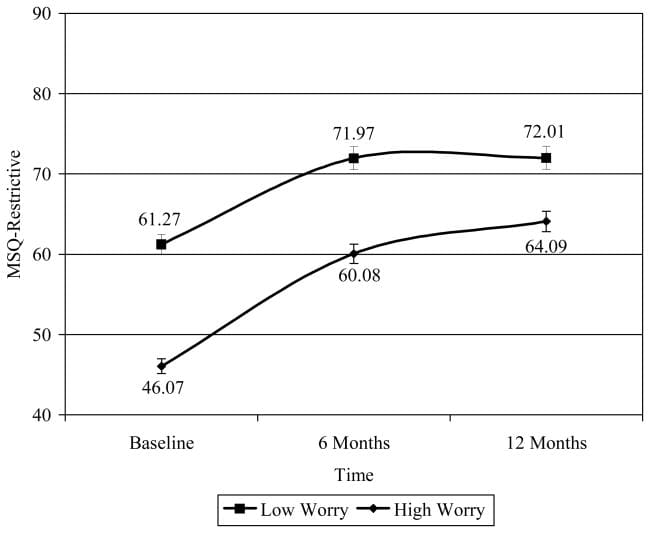

MSQ-R. Results indicate that the main effect for time was significant (F [2, 472] = 47.60, p < .001). Figure 4 shows MSQ-R for each time point by level of worry. Relative to baseline (M = 53.67, SD = 1.23), MSQ-R was significantly improved at 6 months (M = 66.02, SD = 1.35) (CID = 8.96�13.75) and at 12 months (M = 68.05, SD = 1.38) (CID = 10.34�18.42). No difference was found comparing 6 month and 12 month MSQ-R scores. The main effect for worry was significant (F [1, 281] = 34.86, p < .001) such that those with High Worry had significantly lower quality of life (M = 56.75, SD = 1.17) than those with Low Worry (M = 68.41, SD = 1.60) (CID = 7.78�15.57). The main effect for self-efficacy was significant (F [1, 281] = 7.89, p < .01) such that those with Low Self-Efficacy had significantly lower quality of life (M = 59.81, SD = 1.35) than those with Low Worry (M = 65.36, SD = 1.45) (CID = 1.67�9.44). Neither the main effect for self-efficacy or the time X confidence interaction was significant.

Figure 4: MSQ-R at each time point by worry.

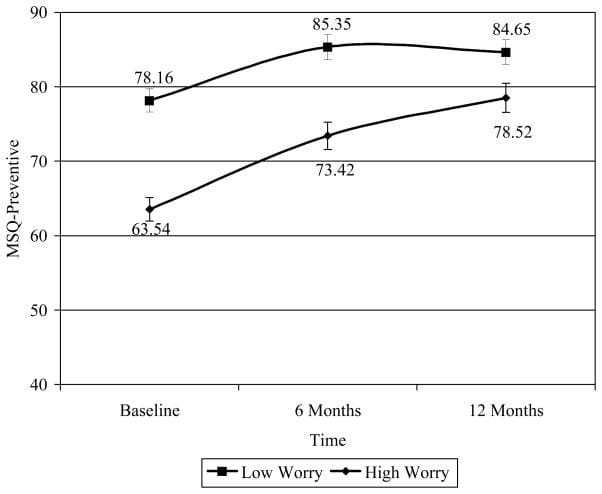

MSQ-P. Results indicate that the time X worry interaction was significant (F [2, 449] = 4.01, p < .05). Figure 5 shows MSQ-P scores for each time point by level of worry. Simple effects analysis showed that those with High Worry showed significant improvement comparing baseline to 6 months and 12 months, and from 6 month to 12 months, while those with Low Worry showed significant improvement comparing baseline to 6 months and 12 months, but no significant improvement from 6 months to 12 months. The main effect for confidence was significant (F [1, 272] = 4.11, p < .05) such that those with Low Self-Efficacy (M = 75.08, SD = 1.48) had lower quality of life than those with High Self-Efficacy (M = 79.47, SD = 1.58) (CID = .13�8.65). The time X self-efficacy interaction and the worry X self-efficacy interaction were not significant.

Figure 5: MSQ-P at each time point.

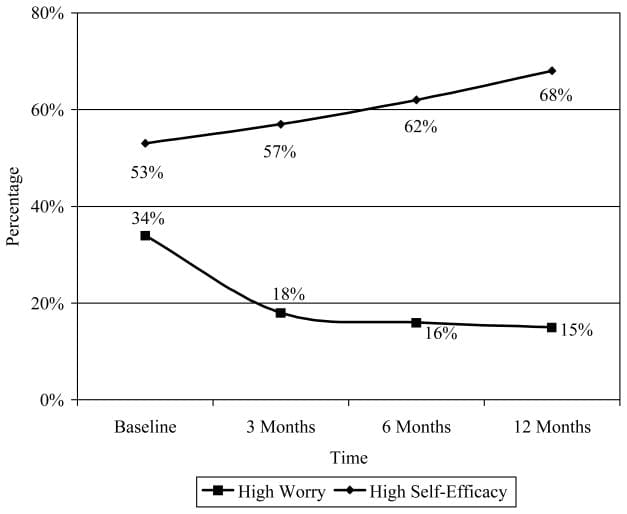

Worry about headaches. Figure 6 shows the percentage of individuals with High Worry at baseline, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months. Results indicated that when compared to baseline, the percentage of individuals with High Worry was significantly less at 3 months (?2 [223] = 20.42, p < .001), 6 months (?2 [223] = 29.98, p < .001), and 12 months (?2 [223] = 29.82, p < .001). No other significant differences were found.

Figure 6: Percentage of individuals with high worry and high self-efficacy at each time point.

Self-Efficacy for managing headaches. Figure 6 shows the percentage of individuals with High Self-Efficacy at baseline, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months. Results indicated that the percentage of individuals with High Self-Efficacy at 12 months was significantly more than at baseline (?2 [223] = 10.92, p < .001) and 3 months (?2 [223] = 8.02, p < .001). No other significant differences were found.

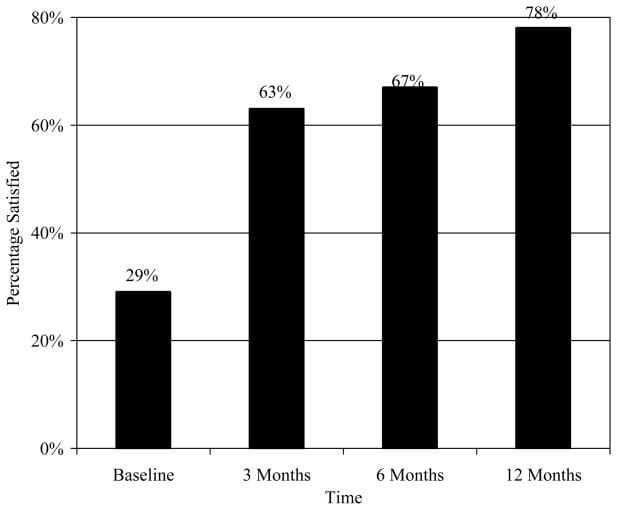

Satisfaction. Figure 7 shows the percentage of individuals who were satisfied with their headache care. Results indicated that when compared to baseline, the percentage of individuals who were satisfied with their headache care was significantly higher at 3 months (?2 [223] = 66.39, p < .001), 6 months (?2 [223] = 75.87, p < .001), and 12 months (?2 [223] = 100.99, p < .001). Also, the percentage of individuals who were satisfied with their headache care at 12 months was significantly higher than at 3 months (?2 [223] = 16.25, p < .001) and 6 months (?2 [223] = 9.80, p < .001). No other significant differences were found.

Figure 7: Satisfaction with headache care.

ER visits. Results indicated that at baseline, 8.33% (n=19) has gone to the ER for headache in the previous 3 months. Although there was a decrease in ER visits at 3 months (3.08%; n= 7), 6 months (3.95%; n = 9), and 12 months (5.26%; n = 12), these reductions were not significant.

Discussion

The primary outcome was the impact that the MMMP would have on headache frequency. Almost half (46%) of all participants reported a 50% or greater reduction in headache frequency at 12 months. It is notable that the percentage of participants experiencing a >50% reduction in headache frequency increased steadily over the 12 months, showing a lasting effect of the educational intervention. The degree of change was not significantly greater in either High Worry or Low Worry groups. However, the reduction in HIT-6 scores was significantly greater for those with High Worry compared to those with Low Worry at 3 months after baseline. In a related finding, participants with Low Self-Efficacy at baseline reported significantly greater reduction in headache impact than those with High Self-Efficacy. It is likely that this was due to participants gaining greater confidence in their own ability to manage their headaches through the education and headache management skills provided in the MMMP. This hypothesis is supported by the increasing percentage of participants with High Self-Efficacy scores and declining percentage of subjects with High Worry over the 12 month study period.

Participants reported that headache-related disability decreased and quality of life improved during the course of the study. This is an encouraging finding given that most patients seek treatment for headaches due to the disability and burden of disease. It is notable that this improvement was achieved through a low-cost, easy to administer educational program. The results also showed that patients worried less about their headaches. It has been well established among chronic pain patients that anxiety and worry about impending pain can significantly increase pain and inhibit efficacy of analgesic therapies.[48�49] To date, however, little research has looked at these phenomena among those with migraine. What research has been conducted has found that worry and anxiety appear to be a significant issue in migraine.[50�54]

It is interesting to note the interactions of worry with disability and quality of life. The focus of the current intervention was solely on education. Not enough research has been published to fully establish the importance of education in changing disease outcomes, particularly as it relates to headache pain. Perhaps the education and basic headache management skills provided in the education program equipped patients with enough knowledge and basic skills that worry and anxiety about headaches were reduced. This idea is supported by the finding that those with high worry at the beginning of the study reported the greatest amount of improvement on ratings of disability and quality of life.

The finding that satisfaction was higher serves as an encouragement that an intervention that is low cost and easy to administer can have a positive impact on patients� perception of care. There are a number of possibilities as to why this may have occurred. It could be that as a result of their education the health care providers were able to better answer patients� questions about migraine and its management. It is possible that the educational materials distributed to the patients resulted in their becoming more knowledgeable about migraine and, in turn, more satisfied with their care. It is also possible that the greater satisfaction came from having fewer headaches and headaches that were less disabling. The current study was not designed to answer these mechanistic questions, thus it is difficult to determine the influence of each of these variables on patient satisfaction. In regards to ER visits; although there was a decrease in ER visits at each time point, the percentage of individuals who had gone to the ER at baseline (8.33%) was low enough that there was little chance to see significant decline.

The results of this study imply that increased knowledge about migraine and management skills can lessen the burden of disease. This is congruent with research in other chronic disease areas (e.g., diabetes, asthma, cardiovascular disease) where providing patients with education about their disease state has been demonstrated to reduce disease burden and reduce worry and anxiety.

Although the current study is encouraging in its findings and raises the specter of future research into the disease management benefits of migraine education, there are limitations to the current study. Likely the greatest limitation to the study was the lack of a parallel condition. Not including such a condition did not allow us to evaluate the possibility that the results emanated from a positive bias or even a �self-fulfilling� outcome whereby decreases in headache were a function of participants� expectations. However, in the current study, the issue of positive bias may have been lessened by the fact the participants had no regular direct interaction with the researchers, and what interaction occurred did so at 3 or more month intervals. At the same time, with a lack of a control condition, this possibility cannot be discounted. This study was undertaken in an effort to see whether an approach that involved a one-time contact would have any impact on headache and associated outcomes. As a result, the conclusions that can be drawn from the current study are limited.

There was no formal oversight of prophylactic prescription patterns, so it is possible that the improvements seen in the participants was due to the 15% increase in the number of individuals prescribed migraine prophylaxis. However, a regression analysis was conducted to evaluate the possibility that starting migraine prophylaxis predicted improvement on the various outcomes (headache frequency, disability, quality of life, worry, satisfaction with care) at each time point. Starting migraine prophylaxis predicted a decrease in headache frequency at 3 months, but had no significant influence on any other domains at any time point. Another limitation was the lack of a parallel comparison group that did not receive the educational intervention. It is possible that the reported improvements in all these domains is a result of positive response bias. Another area of concern is that the scales and questionnaires were based on patient recall rather than diaries, allowing for recall bias. It is also possible that the physicians who participated in the educational seminar tend to have a more interactive communication approach with their patients which can have a positive influence on patient management.[50]

In summary, the purpose of the current study was to evaluate the efficacy of the MMMP which provided education about migraine and its management to health care providers and persons with migraine. In this open-label trial that utilized a linear random mixed model to evaluate change over a 12-month period, patients who participated reported fewer headaches, less disability, and improved quality of life. Also, a significant proportion of the patients reported having less worry, increased self-efficacy, and greater satisfaction with their migraine treatment. It is also worthwhile to note that the increased satisfaction, decreased worry and improved quality of life scores demonstrated in this program were achieved through a low-cost, easy to administer educational program.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. Mitzi Corzine and Ms. Sally Kane at St. John�s Mercy Health Research (for managing the project), the health care providers and practices in the St. John�s Mercy Medical Group who participated, and Dr. Timothy Houle (statistical assistance). This project was funded by small unrestricted grants provided by the Primary Care Network, GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals, and Abbott Laboratories. The manuscript was prepared while the second author was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NINDS #K23NS048288).

In conclusion,�despite the fact that headache is one of the most prevalent reasons for doctor office visits each year, migraine still continues to be one of the most underdiagnosed and undertreated diseases in the medical field, impacting the overall health as wellness of migraine sufferers around the world. According to the findings of the article above, patients who participated in the Mercy Migraine Management Program, or MMMP, reported improvements in their migraine symptoms. Furthermore, migraineurs demonstrated additional improvements in a variety of other headache treatment options. Information referenced from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic as well as to spinal injuries and conditions. To discuss the subject matter, please feel free to ask Dr. Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

Curated by Dr. Alex Jimenez

Additional Topics: Back Pain

According to statistics, approximately 80% of people will experience symptoms of back pain at least once throughout their lifetimes. Back pain is a common complaint which can result due to a variety of injuries and/or conditions. Often times, the natural degeneration of the spine with age can cause back pain. Herniated discs occur when the soft, gel-like center of an intervertebral disc pushes through a tear in its surrounding, outer ring of cartilage, compressing and irritating the nerve roots. Disc herniations most commonly occur along the lower back, or lumbar spine, but they may also occur along the cervical spine, or neck. The impingement of the nerves found in the low back due to injury and/or an aggravated condition can lead to symptoms of sciatica.

EXTRA IMPORTANT TOPIC: Migraine Pain Treatment

MORE TOPICS: EXTRA EXTRA: El Paso, Tx | Athletes