Sacral Plexus Rundown

The lumbosacral plexus is located on the posterolateral wall of the lesser pelvis, next to the lumbar spine. A plexus is a network of intersecting nerves that share roots, branches, and functions. The sacral plexus is a network that emerges from the lower part of the spine. The plexus then embeds itself into the psoas major muscle and emerges in the pelvis. These nerves provide motor control to and receive sensory information from portions of the pelvis and leg. Sacral nerve discomfort symptoms, numbness, or other sensations and pain can be caused by an injury, especially if the nerve roots are compressed, tangled, rubbing, and irritated. This can cause symptoms like back pain, pain in the back and sides of the legs, sensory issues affecting the groin and buttocks, and bladder or bowel problems. Injury Medical Chiropractic and Functional Medicine Clinic can develop a personalized treatment plan to relieve symptoms, release the nerves, relax the muscles, and restore function.

Sacral Plexus

Anatomy

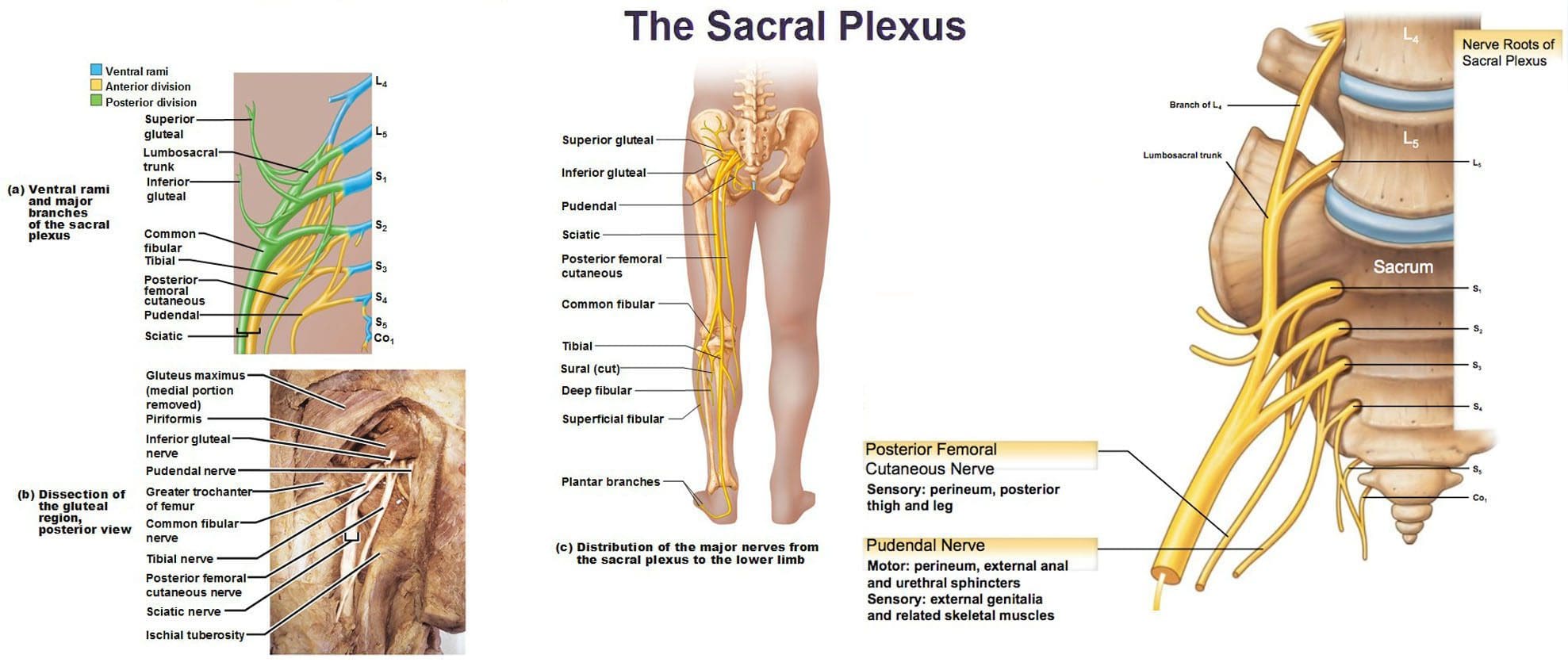

- The sacral plexus is formed by the lumbar spinal nerves, L4 and L5, and sacral nerves S1 through S4.

- Several combinations of these spinal nerves merge together and then divide into the branches of the sacral plexus.

- Everybody has two sacral plexi – plural of plexus – one on the right side and left side that is symmetrical in structure and function.

Structure

There are several plexi throughout the body. The sacral plexus covers a large area of the body in terms of motor and sensory nerve function.

- Spinal nerves L4 and L5 make up the lumbosacral trunk, and the anterior rami of sacral spinal nerves S1, S2, S3, and S4 join the lumbosacral trunk to form the sacral plexus.

- Anterior rami are the branches of the nerve that are towards the front of the spinal cord/front of the body.

- At each spinal level, an anterior motor root and a posterior sensory root join to form a spinal nerve.

- Each spinal nerve then divides into an anterior – ventral – and a posterior – dorsal – rami portion.

- Each can have motor and/or sensory functions.

The sacral plexus divides into several nerve branches, which include:

- Superior gluteal nerve – L4, L5, and S1.

- Inferior gluteal nerve – L5, S1, and S2.

- The sciatic nerve – is the largest nerve of the sacral plexus and among the largest nerves in the body – L4, L5, S1, S2, and S3

- The common fibular nerve – L4 through S2, and tibial nerves – L4 through S3 are branches of the sciatic nerve.

- Posterior femoral cutaneous nerve – S1, S2, and S3.

- Pudendal nerve – S2, S3, and S4.

- The nerve to the quadratus femoris muscle is formed by L4, L5, and S1.

- The obturator internus muscle nerve – L5, S1, and S2.

- The piriformis muscle nerve – S1 and S2.

Function

The sacral plexus has substantial functions throughout the pelvis and legs. The branches provide nerve stimulation to several muscles. The sacral plexus nerve branches also receive sensory messages from the skin, joints, and structures of the pelvis and legs.

Motor

Motor nerves of the sacral plexus receive signals from the brain that travel down the column of the spine, out to the motor nerve branches of the sacral plexus to stimulate muscle contraction and movement. Motor nerves of the sacral plexus include:

Superior Gluteal Nerve

- This nerve provides stimulation to the gluteus minimus, gluteus medius, and tensor fascia lata, which are muscles that help move the hip away from the center of the body.

Inferior Gluteal Nerve

- This nerve provides stimulation to the gluteus maximus, the large muscle that moves the hip laterally.

Sciatic Nerve

- The sciatic nerve has a tibial portion and a common fibular portion, which have motor and sensory functions.

- The tibial portion stimulates the inner part of the thigh and activates muscles in the back of the leg and the sole of the foot.

- The common fibular portion of the sciatic nerve stimulates and moves the thigh and knee.

- The common fibular nerve stimulates muscles in the front and sides of the legs and extends the toes to straighten them out.

Pudendal Nerve

- The pudendal nerve also has sensory functions that stimulate the muscles of the urethral sphincter to control urination and the muscles of the anal sphincter to control defecation.

- The nerve to the quadratus femoris stimulates the muscle to move the thigh.

- The nerve to the obturator internus muscle stimulates the muscle to rotate the hips and stabilize the body when walking.

- The nerve to the piriformis muscle stimulates the muscle to move the thigh away from the body.

Conditions

The sacral plexus, or areas of the plexus, can be affected by disease, traumatic injury, or cancer. Because the nerve network has many branches and portions, symptoms can be confusing. Individuals may experience sensory loss or pain in regions in the pelvis and leg, with or without muscle weakness. Conditions that affect the sacral plexus include:

Injury

- A traumatic injury of the pelvis can stretch, tear, or harm the sacral plexus nerves.

- Bleeding can inflame and compress the nerves, causing malfunction.

Neuropathy

- Nerve impairment can affect the sacral plexus or parts of it.

- Neuropathy can come from:

- Diabetes

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Certain medications – chemotherapeutic meds

- Toxins like lead

- Alcohol

- Metabolic illnesses

Infection

- An infection of the spine or the pelvic region can spread to the sacral plexus nerves or produce an abscess, causing symptoms of nerve impairment, pain, tenderness, and sensations around the infected region.

Cancer

- Cancer developing in the pelvis or spreading to the pelvis from somewhere else can compress or infect the sacral plexus nerves.

Treatment of the Underlying Medical Condition

Rehabilitation begins with the treatment of the underlying medical condition causing the nerve problems.

- Cancer treatment – surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation.

- Antibiotic treatment for infections.

- Neuropathy treatment can be complicated because the cause may be unclear, and an individual can experience several causes of neuropathy simultaneously.

- Major pelvic trauma like a vehicle collision can take months, especially if there are multiple bone fractures.

Motor and Sensory Recovery

- Sensory problems can interfere with walking, standing, and sitting.

- Adapting to sensory deficits is an important part of treatment, rehabilitation, and recovery.

- Chiropractic, decompression, massage, and physical therapy can relieve symptoms, restore strength, function, and motor control.

Sciatica Secrets Revealed

References

Dujardin, Franck et al. “Extended anterolateral transiliac approach to the sacral plexus.” Orthopaedics & traumatology, surgery & research: OTSR vol. 106,5 (2020): 841-844. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2020.04.011

Eggleton JS, Cunha B. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Pelvic Outlet. [Updated 2022 Aug 22]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557602/

Garozzo, Debora et al. “In lumbosacral plexus injuries can we identify indicators that predict spontaneous recovery or the need for surgical treatment? Results from a clinical study on 72 patients.” Journal of brachial plexus and peripheral nerve injury vol. 9,1 1. 11 Jan. 2014, doi:10.1186/1749-7221-9-1

Gasparotti R, Shah L. Brachial and Lumbosacral Plexus and Peripheral Nerves. 2020 Feb 15. In: Hodler J, Kubik-Huch RA, von Schulthess GK, editors. Diseases of the Brain, Head and Neck, Spine 2020–2023: Diagnostic Imaging [Internet]. Cham (CH): Springer; 2020. Chapter 20. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554335/ doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-38490-6_20

Norderval, Stig, et al. “Sacral nerve stimulation.” Tidsskrift for den Norske laegeforening : tidsskrift for praktisk medicin, ny raekke vol. 131,12 (2011): 1190-3. doi:10.4045/tidsskr.10.1417

Neufeld, Ethan A et al. “MR Imaging of the Lumbosacral Plexus: A Review of Techniques and Pathologies.” Journal of Neuroimaging: official journal of the American Society of Neuroimaging vol. 25,5 (2015): 691-703. doi:10.1111/jon.12253

Staff, Nathan P, and Anthony J Windebank. “Peripheral neuropathy due to vitamin deficiency, toxins, and medications.” Continuum (Minneapolis, Minn.) vol. 20,5 Peripheral Nervous System Disorders (2014): 1293-306. doi:10.1212/01.CON.0000455880.06675.5a

Yin, Gang, et al. “Obturator Nerve Transfer to the Branch of the Tibial Nerve Innervating the Gastrocnemius Muscle for the Treatment of Sacral Plexus Nerve Injury.” Neurosurgery vol. 78,4 (2016): 546-51. doi:10.1227/NEU.0000000000001166