Chiropractic for Low Back Pain and Sciatica

Chiropractic Management of Low Back Pain and Low Back-Related Leg Complaints: A Literature Synthesis

Chiropractic care is a well-known complementary and alternative treatment option frequently used to diagnose, treat and prevent injuries and conditions of the musculoskeletal and nervous systems. Spinal health issues are among some of the most common reasons people seek chiropractic care, especially for low back pain and sciatica complaints. While there are many different types of treatments available to help improve low back pain and sciatica symptoms, many individuals will often prefer natural treatment options over the use of drugs/medications or surgical interventions. The following research study demonstrates a list of evidence-based chiropractic treatment methods and their effects towards improving a variety of spinal health issues.

Abstract

- Objectives: The purpose of this project was to review the literature for the use of spinal manipulation for low back pain (LBP).

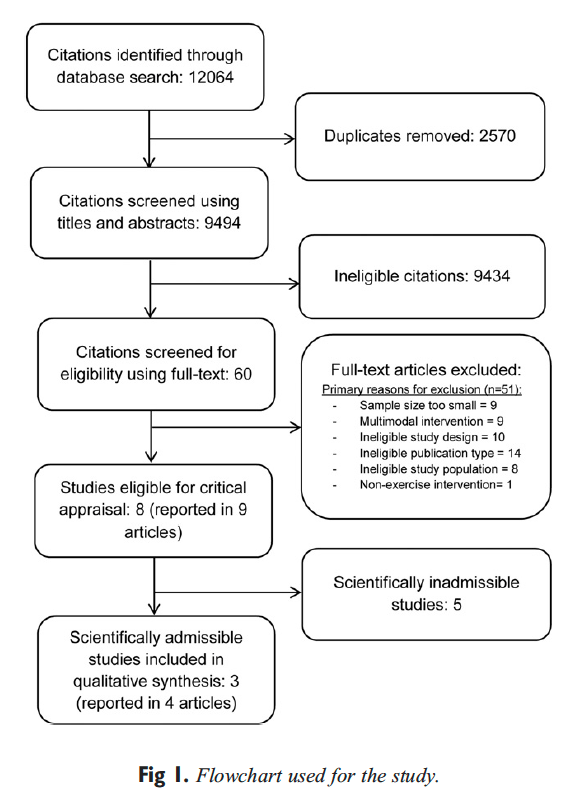

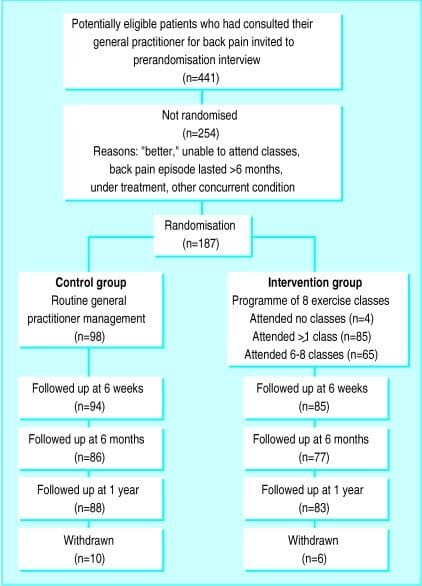

- Methods: Asearch strategymodified fromthe Cochrane Collaboration reviewforLBP was conducted through the following databases: PubMed, Mantis, and the Cochrane Database. Invitations to submit relevant articles were extended to the profession via widely distributed professional news and association media. The Scientific Commission of the Council on Chiropractic Guidelines and Practice Parameters (CCGPP) was charged with developing literature syntheses, organized by anatomical region, to evaluate and report on the evidence base for chiropractic care. This article is the outcome of this charge. As part of the CCGPP process, preliminary drafts of these articles were posted on the CCGPP Web site www.ccgpp.org (2006-8) to allow for an open process and the broadest possible mechanism for stakeholder input.

- Results: A total of 887 source documents were obtained. Search results were sorted into related topic groups as follows: randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of LBP and manipulation; randomized trials of other interventions for LBP; guidelines; systematic reviews and meta-analyses; basic science; diagnostic-related articles, methodology; cognitive therapy and psychosocial issues; cohort and outcome studies; and others. Each group was subdivided by topic so that team members received approximately equal numbers of articles from each group, chosen randomly for distribution. The team elected to limit consideration in this first iteration to guidelines, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, RCTs, and coh ort studies. This yielded a total of 12 guidelines, 64 RCTs, 13 systematic reviews/meta-analyses, and 11 cohort studies.

- Conclusions: As much or more evidence exists for the use of spinal manipulation to reduce symptoms and improve function in patients with chronic LBP as for use in acute and subacute LBP. Use of exercise in conjunction with manipulation is likely to speed and improve outcomes as well as minimize episodic recurrence. There was less evidence for the use of manipulation for patients with LBP and radiating leg pain, sciatica, or radiculopathy. (J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2008;31:659-674)

- Key Indexing Terms: Low Back Pain; Manipulation; Chiropractic; Spine; Sciatica; Radiculopathy; Review, Systematic

The Council on Chiropractic Guidelines and Practice Parameters (CCGPP) was formed in 1995 by the Congress of Chiropractic State Associations with assistance from the American Chiropractic Association, Association of Chiropractic Colleges, Council on Chiropractic Education, Federation of Chiropractic Licensing�Boards, Foundation for the Advancement of Chiropractic Sciences, Foundation for Chiropractic Education and Research, International Chiropractors Association, National Association of Chiropractic Attorneys, and the National Institute for Chiropractic Research. The charge to the CCGPP was to create a chiropractic �best practices� document. The Council on Chiropractic Guidelines and Practice Parameters was delegated to examine all existing guidelines, parameters, protocols, and best practices in the United States and other nations in the construction of this document.

Toward that end, the Scientific Commission of CCGPP was charged with developing literature syntheses, organized by region (neck, low back, thoracic, upper and lower extremity, soft tissue) and the nonregional categories of nonmusculoskeletal, prevention/health promotion, special populations, subluxation, and diagnostic imaging.

The purpose of this work is to provide a balanced interpretation of the literature to identify safe and effective treatment options in the care of patients with low back pain (LBP) and related disorders. This evidence summary is intended to serve as a resource for practitioners to assist them in consideration of various care options for such patients. It is neither a replacement for clinical judgment nor a prescriptive standard of care for individual patients.

Methods

Process development was guided by experience of commission members with the RAND consensus process, Cochrane collaboration, Agency for Health Care and Policy Research, and published recommendations modified to the needs of the council.

Identification and Retrieval

The domain for this report is that of LBP and low backrelated leg symptoms. Using surveys of the profession and publications on practice audits, the team selected the topics for review by this iteration.

Topics were selected based on the most common disorders seen and most common classifications of treatments used by chiropractors based on the literature. Material for review was obtained through formal hand searches of published literature and of electronic databases, with assistance from a professional chiropractic college librarian. A search strategy was developed, based upon the CochraneWorking Group for Low Back Pain. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), systematic reviews/meta-analyses, and guidelines published through 2006 were included; all other types of studies were included through 2004. Invitations to submit relevant articles were extended to the profession via widely distributed professional news and association media. Searches focused on guidelines, meta-analyses, systematic reviews, randomized clinical trials, cohort studies, and case series.

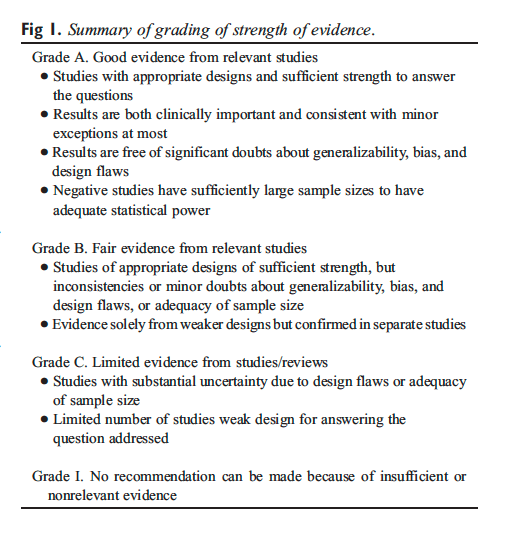

Evaluation

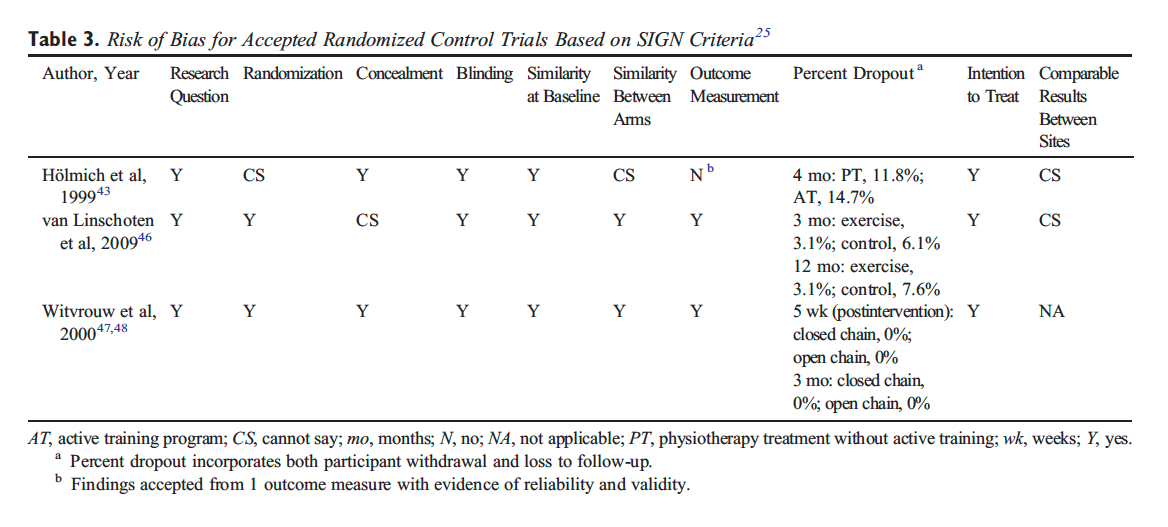

Standardized and validated instruments used by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network were used to evaluate RCTs and systematic reviews. For guidelines, the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation instrument was used. A standardized method for grading the strength of the evidence was used, as summarized in Figure 1. Each team’s multidisciplinary panel conducted the review and evaluation of the evidence.

Search results were sorted into related topic groups as follows: RCTs of LBP and manipulation; randomized trials of other interventions for LBP; guidelines; systematic reviews and meta-analyses; basic science; diagnosticrelated articles; methodology; cognitive therapy and psychosocial issues; cohort and outcome studies; and others. Each group was subdivided by topic so that team members received approximately equal numbers of articles from each group, chosen randomly for distribution. On the basis of the CCGPP formation of an iterative process and the volume of work available, the team elected to limit consideration in this first iteration to guidelines, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, RCTs, and cohort studies.

Dr. Alex Jimenez’s Insight

How does chiropractic care benefit people with low back pain and sciatica?�As a chiropractor experienced in the management of a variety of spine health issues, including low back pain and sciatica, spinal adjustments and manual manipulations, as well as other non-invasive treatment methods, can be safely and effectively implemented towards the improvement of back pain symptoms. The purpose of the following research study is to demonstrate the evidence-based effects of chiropractic in the treatment of injuries and conditions of the musculoskeletal and nervous systems. The information in this article can educate patients on how alternative treatment options can help improve their low back pain and sciatica. As a chiropractor, patients may also be referred to other healthcare professionals, such as physical therapists, functional medicine practitioners and medical doctors, to help them further manage their low back pain and sciatica symptoms. Chiropractic care can be used to avoid surgical interventions for spine health issues.

Results and Discussion

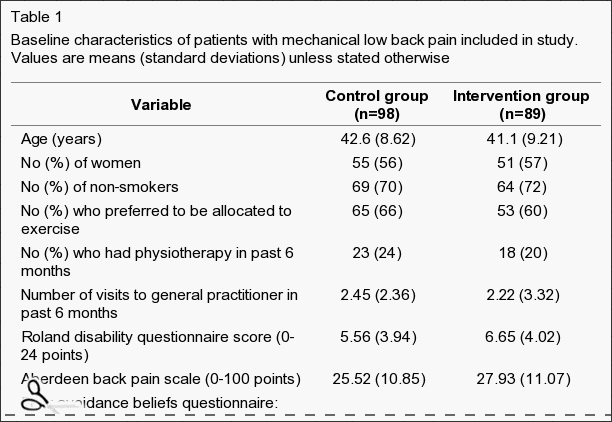

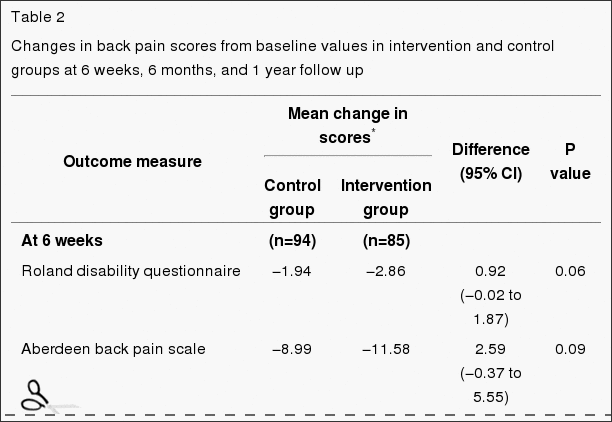

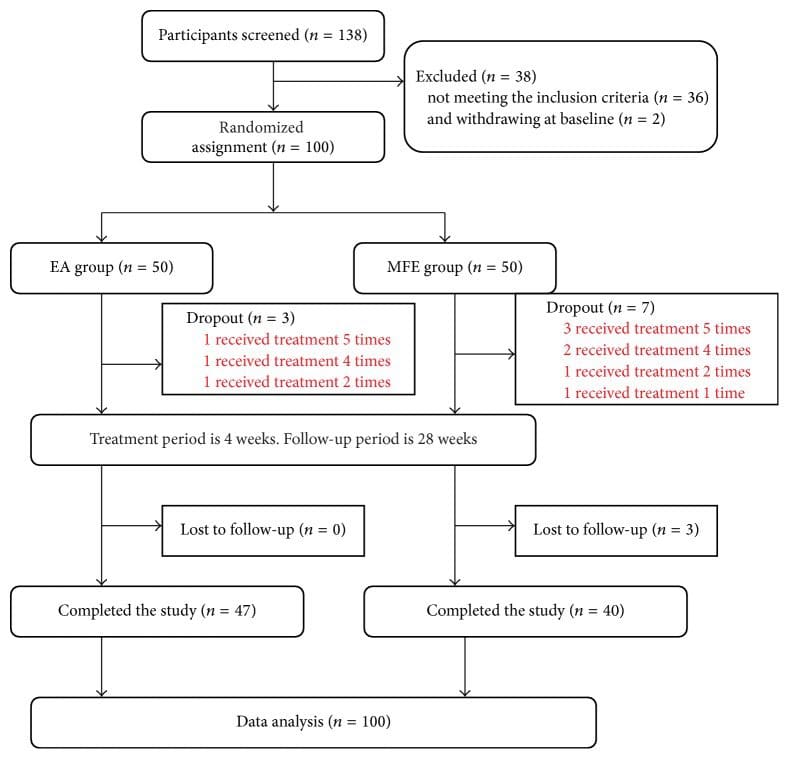

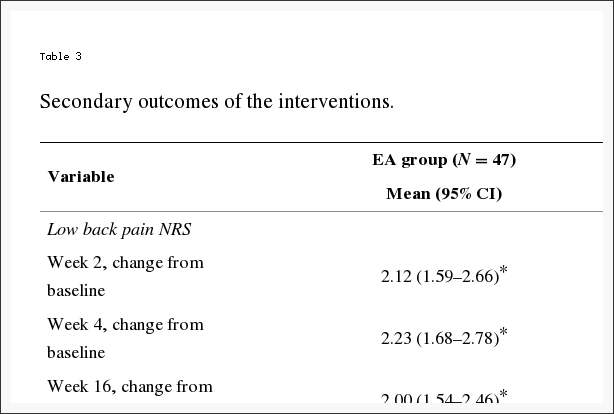

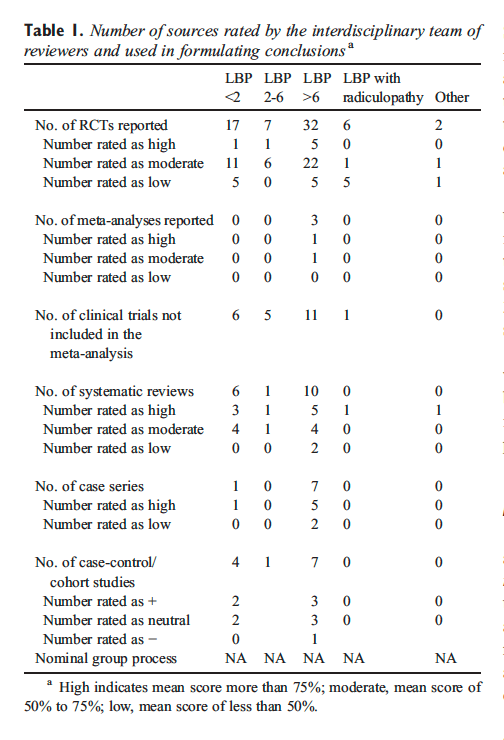

A total of 887 source documents were initially obtained. This included a total of 12 guidelines, 64 RCTs, 20 systematic reviews/meta-analyses, and 12 cohort studies. Table 1 provides an overall summary of the number of studies evaluated.

Assurance and Advice

The search strategy used by the team was that developed by van Tulder et al, and the team identified 11 trials. Good evidence indicates that patients with acute LBP on bed rest have more pain and less functional recovery than those who stay active. There is no difference in pain and functional status between bed rest and exercises. For sciatica patients, fair evidence shows no real difference in pain and functional status between bed rest and staying active. There is fair evidence of no difference in pain intensity between bed rest and physiotherapy but small improvements in functional status. Finally, there is little difference in pain intensity or functional status between shorter-term or longer-term bed rest.

A Cochrane review by Hagen et al demonstrated small advantages in short-term and long-term for staying active over bed rest, as did a high-quality review by the Danish Society of Chiropractic and Clinical Biomechanics, including 4 systematic reviews, 4 additional RCTS, and 6 guidelines, on acute LBP and sciatica. The Cochrane review by Hilde et al included 4 trials and concluded a small beneficial effect for staying active for acute, uncomplicated LBP, but no benefit for sciatica. Eight studies on staying active and 10 on bed rest were included in an analysis by the group of Waddell. Several therapies were coupled with advice to stay active and include analgesic medication, physical therapy, back school, and behavioral counseling. Bed rest for acute LBP was similar to no treatment and placebo and less effective than alternative treatment. Outcomes considered across the studies were rate of recovery, pain, activity levels, and work time loss. Staying active was found to have a favorable effect.

Review of 4 studies not covered elsewhere assessed the use of brochures/booklets. The trend was for no differences in outcome for pamphlets. One exception was noted�that those who received manipulation had less bothersome symptoms at 4 weeks and significantly less disability at 3 months for those who received a booklet encouraging staying active.

In summary, assuring patients that they are likely to do well and advising them to stay active and avoid bed rest is a best practice for management of acute LBP. Bed rest for short intervals may be beneficial for patients with radiating leg pain who are intolerant of weight bearing.

Adjustment/Manipulation/Mobilization Vs Multiple Modalities

This review considered literature on high-velocity, lowamplitude (HVLA) procedures, often termed adjustment or manipulation, and mobilization. The HVLA procedures use thrusting maneuvers applied quickly; mobilization is applied cyclically. The HVLA procedure and mobilization may be mechanically assisted; mechanical impulse devices are considered HVLA, and flexion-distraction methods and continuous passive motion methods are within mobilization.

The team recommends adopting the findings of the systematic review by Bronfort et al, with a quality score (QS) of 88, covering literature up to 2002. In 2006, the Cochrane collaboration reissued an earlier (2004) review of spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) for back pain performed by Assendelft et al. This reported on 39 studies up to 1999, several overlapping with those reported by Bronfort et al using different criteria and a novel analysis. They report no difference in outcome from treatment with manipulation vs alternatives. As several additional RCTs had appeared in the interim, the rationale for reissuing the older review without acknowledging new studies was unclear.

Acute LBP. There was fair evidence that HVLA has better short-term efficacy than mobilization or diathermy and limited evidence of better short-term efficacy than diathermy, exercise, and ergonomic modifications.

Chronic LBP. The HVLA procedure combined with strengthening exercise was as effective for pain relief as nonsteroidal antiinflammatory dugs with exercise. Fair evidence indicated that manipulation is better than physical therapy and home exercise for reducing disability. Fair evidence shows that manipulation improves outcomes more than general medical care or placebo in the short-term and to physical therapy in the long-term. The HVLA procedure had better outcomes than home exercise, transcutaneous�electrical nerve stimulation, traction, exercise, placebo and sham manipulation, or chemonucleolysis for disk herniation.

Mixed (Acute and Chronic) LBP. Hurwitz found that HVLA was the same as medical care for pain and disability; adding physical therapy to manipulation did not improve outcomes. Hsieh found no significant value for HVLA over back school or myofascial therapy. A short-term value of manipulation over a pamphlet and no difference between manipulation and McKenzie technique were reported by Cherkin et al. Meade contrasted manipulation and hospital care, finding greater benefit for manipulation over both short-term and long-term. Doran and Newell found that SMT resulted in greater improvement than physical therapy or corsets.

Acute LBP

Sick List Comparisons. Seferlis found that sick patients listed were significantly improved symptomatically after 1 month regardless of the intervention, including manipulation. Patients were more satisfied and felt that they were provided better explanations about their pain from practitioners who used manual therapy (QS, 62.5). Wand et al examined the effects of sick-listing oneself and noted that a group receiving assessment, advice, and treatment improved better than did a group getting assessment, advice, and who were put on a wait list for a 6-week period. Improvements were observed in disability, general health, quality of life, and mood, though pain and disability were not different at longterm follow-up (QS, 68.75).

Physiologic Therapeutic Modality and Exercise. Hurley and colleagues tested the effects of manipulation combined with interferential therapy compared to either modality alone. Their results showed all 3 groups improved function to the same degree, both at 6-month and at 12-month follow-up (QS, 81.25). Using a single-blinded experimental design to compare manipulation to massage and low-level electrostimulation, Godfrey et al found no differences between groups at the 2 to 3-week observation time frame (QS, 19). In the study by Rasmussen, results showed that 94% of the patients treated with manipulation were symptom-free within 14 days, compared to 25% in the group that received short-wave diathermy. Sample size was small, however, and as a result, the study was underpowered (QS, 18). The Danish systematic review examined 12 international sets of guidelines, 12 systematic reviews, and 10 randomized clinical trials on exercise. They found no specific exercises, regardless of type, that were useful for the treatment of acute LBP with the exception of McKenzie maneuvers.

Sham and Alternate Manual Method Comparisons. The study of Hadler balanced for effects of provider attention and physical contact with a first effort at a manipulation sham procedure. Patients in the group that entered the trial with greater prolonged illness at the outset were reported to have benefited from the manipulation. Similarly, they improved faster and to a greater degree (QS, 62.5). Hadler demonstrated that there was a benefit for a single session of manipulation compared to a session of mobilization (QS, 69). Erhard reported that the rate of positive response to manual treatment with a hand-heel rocking motion was greater than with extension exercises (QS, 25). Von Buerger examined the use of manipulation for acute LBP, comparing rotational manipulation to soft tissue massage. He found that the manipulation group responded better than the soft tissue group, although the effects occurred mainly in the short-term. The results were also hampered by the nature of the forced multiple choice selections on the data forms (QS, 31). Gemmell compared 2 forms of manipulation for LBP of less than 6 weeks of duration as follows: Meric adjusting (a form of HVLA) and Activator technique (a form of mechanically assisted HVLA). No difference was observed, and both helped to reduce pain intensity (QS, 37.5). MacDonald reported a short-term benefit in disability measures within the first 1 to 2 weeks of starting therapy for the manipulation group that disappeared by 4 weeks in a control group (QS, 38). The work of Hoehler, although containing mixed data for patients with acute and chronic LBP, is included here because a larger proportion of patients with acute LBP were involved in the study. Manipulation patients reported immediate relief more often, but there were no differences between groups at discharge (QS, 25).

Medication. Coyer showed that 50% of the manipulation group was symptom-free within 1 week and 87% were discharged symptom-free in 3 weeks, compared to 27% and 60%, respectively, of the control group (bed rest and analgesics) (QS, 37.5). Doran and Newell compared manipulation, physiotherapy, corset, or analgesic medication, using outcomes that examined pain and mobility. There were no differences between groups over time (QS, 25). Waterworth compared manipulation to conservative physiotherapy and 500 mg of diflunisal twice per day for 10 days. Manipulation showed no benefit for the rate of recovery (QS, 62.5). Blomberg compared manipulation to steroid injections and to a control group receiving conventional activating therapy. After 4 months, the manipulation group had less restricted motion in extension, less restriction in side-bending to both sides, less local pain on extension and right sidebending, less radiating pain, and less pain when performing a straight leg raise (QS, 56.25). Bronfort found no outcome differences between chiropractic care compared to medical care at 1 month of treatment, but there were noticeable improvements in the chiropractic group at both 3 and 6-month follow-up (QS, 31).

Subacute Back Pain

Staying Active. Grunnesjo compared combined effects of manual therapy with advice to stay active to advice alone in patients with acute and subacute LBP. The addition of�manual therapy appeared to reduce pain and disability more effectively than the �stay active� concept alone (QS, 68.75).

Physiologic Therapeutic Modality and Exercise. Pope demonstrated that manipulation offered better pain improvement than transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (QS 38). Sims-Williams compared manipulation to �physiotherapy.� Results demonstrated a short-term benefit for manipulation on pain and ability to do light work. Differences between groups waned at 3 and 12-month follow-ups (QS, 43.75, 35). Skargren et al compared chiropractic to physiotherapy for patients with LBP who had no treatment for the prior month. No differences in health improvements, costs, or recurrence rates were noted between the 2 groups. However, based on Oswestry scores, chiropractic performed better for patients who had pain for less than 1 week, whereas the physiotherapy seemed to be better for those who had pain for more than 4 weeks (QS, 50).

The Danish systematic review examined 12 international sets of guidelines, 12 systematic reviews, and 10 randomized clinical trials on exercise. Results suggested that exercise, in general, benefits patients with subacute back pain. Use of a basic program that can be readily modified to meet individual patient needs is recommended. Issues of strength, endurance, stabilization, and coordination without excessive loading can all be addressed without the use of high-tech equipment. Intensive training consisting of greater than 30 and less than 100 hours of training are most effective.

Sham and Alternate Manual Method Comparisons. Hoiriis compared efficacy of chiropractic manipulation to placebo/ sham for subacute LBP. All groups improved on measures of pain, disability, depression, and Global Impression of Severity. Chiropractic manipulation scored better than placebo in reducing pain and Global Impression of Severity scores (QS, 75). Andersson and colleagues compared osteopathic manipulation to standard care to patients with subacute LBP, finding that both groups improved for a 12-week period at about the same rate (QS, 50).

Medication Comparisons. In a separate treatment arm of the study of Hoiriis, the relative efficacy of chiropractic manipulation to muscle relaxants for subacute LBP was studied. In all groups, pain, disability, depression, and Global Impression of Severity decreased. Chiropractic manipulation was more effective than muscle relaxants in reducing Global Impression of Severity scores (QS, 75).

Chronic LBP

Staying Active Comparisons. Aure compared manual therapy to exercise in patients with chronic LBP who were sick listed. Although both groups showed improvements in pain intensity, functional disability, general health, and return to work, the manual therapy group showed significantly greater improvements than did the exercise group for all outcomes. Results were consistent for both the short-term and the longterm (QS, 81.25).

Physician Consult/Medical Care/Education. Niemisto compared combined manipulation, stabilization exercise, and physician consultation to consultation alone. The combined intervention was more effective in reducing pain intensity and disability (QS, 81.25). Koes compared general practitioner treatment to manipulation, physiotherapy, and a placebo (detuned ultrasound). Assessments were made at 3, 6, and 12 weeks. The manipulation group had a quicker and larger improvement in physical function compared to the other therapies. Changes in spinal mobility in the groups were small and inconsistent (QS, 68). In a follow-up report, Koes found during subgroup analysis that improvement in pain was greater for manipulation than for other treatments at 12 months when considering patients with chronic conditions, as well as those who were younger than 40 years (QS, 43). Another study by Koes showed that many patients in the nonmanipulation treatment arms had received additional care during follow-up. Yet, improvement in the main complaints and in physical functioning remained better in the manipulation group (QS, 50). Meade observed that chiropractic treatment was more effective than hospital outpatient care, as assessed using the Oswestry Scale (QS, 31). An RCT conducted in Egypt by Rupert compared chiropractic manipulation, after medical and chiropractic evaluation. Pain, forward flexion, active, and passive leg raise all improved to a greater degree in the chiropractic group; however, the description of alternate treatments and outcomes was ambiguous (QS, 50).

Triano compared manual therapy to educational programs for chronic LBP. There was greater improvement in pain, function, and activity tolerance in the manipulation group, which continued beyond the 2-week treatment period (QS, 31).

Physiologic Therapeutic Modality. A negative trial for manipulation was reported by Gibson (QS, 38). Detuned diathermy was reported to achieve better results over manipulation, although there were baseline differences between groups. Koes studied the effectiveness of manipulation, physiotherapy, treatment by a general practitioner, and a placebo of detuned ultrasound. Assessments were made at 3, 6, and 12 weeks. The manipulation group showed a quicker and better improvement in physical function capacity compared to the other therapies. Flexibility differences between groups were not significant (QS, 68). In a follow-up report, Koes found that a subgroup analysis demonstrated that improvement in pain was greater for those treated with manipulation, both for younger (b40) patients and those with chronic conditions at 12-month follow-up (QS, 43). Despite many patients in the nonmanipulation groups received additional care during follow-up, improvements remained better in the manipulation group than in the physical therapy group (QS, 50). In a separate report by the same group, there were improvements in both the physiotherapy and manual therapy groups with regard to severity of complaints and global perceived effect compared to general practitioner care;�however, the differences between the 2 groups was not significant (QS, 50). Mathews et al found that manipulation hastened recovery from LBP more than the control did.

Exercise Modality. Hemilla observed that SMT led to better long-term and short-term disability reduction compared to physical therapy or home exercise (QS, 63). A second article by the same group found that neither bone-setting nor exercise differed significantly from physical therapy for symptom control, though bone-setting was associated with improved lateral and forward-bending of the spine more than exercise (QS, 75). Coxhea reported that HVLA provided better outcomes when compared to exercise, corsets, traction, or no exercise when studied in the short-term (QS, 25). Conversely, Herzog found no differences between manipulation, exercise, and back education in reducing either pain or disability (QS, 6). Aure compared manual therapy to exercise in patients with chronic LBP who were also sick listed. Although both groups showed improvements in pain intensity, functional disability, and general health and returned to work, the manual therapy group showed significantly greater improvements than did the exercise group for all outcomes. This result persisted for both the short-term and the long-term (QS, 81.25). In the article by Niemisto and colleagues, the relative efficacy of combined manipulation, exercise (stabilizing forms), and physician consultation compared to consultation alone was investigated. The combined intervention was more effective in reducing pain intensity and disability (QS, 81.25). The United Kingdom Beam study found that manipulation followed by exercise achieved a moderate benefit at 3 months and a small benefit at 12 months. Likewise, manipulation achieved a small to moderate benefit at 3 months and a small benefit at 12 months. Exercise alone had a small benefit at 3 months but no benefit at 12 months. Lewis et al found improvement occurred when patients were treated by combined manipulation and spinal stabilization exercises vs use of a 10-station exercise class.

The Danish systematic review examined 12 international sets of guidelines, 12 systematic reviews, and 10 randomized clinical trials on exercise. Results suggested that exercise, in general, benefits patients with chronic LBP. No clear superior method is known. Use of a basic program that can be readily modified to meet individual patient needs is recommended. Issues of strength, endurance, stabilization, and coordination without excessive loading can all be addressed without the use of high-tech equipment. Intensive training consisting of greater than 30 and less than 100 hours of training are most effective. Patients with severe chronic LBP, including those off work, are treated more effectively with a multidisciplinary rehabilitation program. For post surgical rehabilitation, patients starting 4 to 6 weeks after disk surgery under intensive training receive greater benefit than with light exercise programs.

Sham and Alternate Manual Methods. Triano found that SMT produced significantly better results for pain and disability relief for the short-term, than did sham manipulation (QS, 31). Cote found no difference over time or for comparisons within or between the manipulation and mobilization groups (QS, 37.5). The authors posed that failure to observe differences may have been due to low responsiveness to change in the instruments used for algometry, coupled with a small sample size. Hsieh found no significant value for HVLA over back school or myofascial therapy (QS, 63). In the study by Licciardone, a comparison was made between osteopathic manipulation (which includes mobilization and soft tissue procedures as well as HVLA), sham manipulation, and a no-intervention control for patients with chronic LBP. All groups showed improvement. Sham and osteopathic manipulation were associated with greater improvements than seen in the no-manipulation group, but no difference was observed between the sham and manipulation groups (QS, 62.5). Both subjective and objective measures showed greater improvements in the manipulation group compared to a sham control, in a report by Waagen (QS, 44). In the work of Kinalski, manual therapy reduced the time of treatment of patients with LBP and concomitant intervertebral disk lesions. When disk lesions were not advanced, a decreased muscular hypertonia and increased mobility was noted. This article, however, was limited by a poor description of patients and methods (QS, 0).

Harrison et al reported a nonrandomized cohort controlled trial of treatment of chronic LBP consisting of 3-point bending traction designed to increase curvature of the lumbar spine. The experimental group received HVLA for pain control during the first 3 weeks (9 treatments). The control group received no treatment. Follow-up at a mean of 11 weeks showed no change in pain or curvature status for controls but a significant increase in curvature and reduction of pain in the experimental group. Average number of treatments to achieve this result was 36. Long-term followup at 17 months showed retention of benefits. No report of relationship between clinical changes and structural change was given.

Haas and colleagues examined the dose-response patterns of manipulation for chronic LBP. Patients were randomly allocated to groups receiving 1, 2, 3, or 4 visits per week for 3 weeks, with outcomes recorded for pain intensity and functional disability. A positive and clinically important effect of the number of chiropractic treatments on pain intensity and disability at 4 weeks was associated with the groups receiving the higher rates of care (QS, 62.5). Descarreaux et al extended this work, treating 2 small groups for 4 weeks (3 times per week) after 2 baseline evaluations separated by 4 weeks. One group was then treated every 3 weeks; the other did not. Although both groups had lower Oswestry scores at 12 weeks, at 10 months, the improvement only persisted for the extended SMT group.

Medication. Burton and colleagues demonstrated that HVLA led to greater short-term improvements in pain and disability than did chemonucleolysis for managing disk�herniation (QS, 38). Bronfort studied SMT combined with exercise vs a combination of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and exercise. Similar results were obtained for both groups (QS, 81). Forceful manipulation coupled with sclerosant therapy (injection of a proliferant solution composed of dextrose-glycerine-phenol) was compared to lower force manipulation combined with saline injections, in a study by Ongley. The group receiving forceful manipulation with sclerosant fared better than the alternate group, but effects cannot be separated between the manual procedure and the sclerosant (QS, 87.5). Giles and Muller compared HVLA procedures to medication and acupuncture. Manipulation showed greater improvement in frequency of back pain, pain scores, Oswestry, and SF-36 compared to the other 2 interventions. Improvements lasted for 1 year. Weaknesses of the study were use of a compliers-only analysis as intention to treat for the Oswestry, and Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) was not significant.

Sciatica/Radicular/Radiating Leg Pain

Staying Active/Bed Rest. Postacchini studied a mixed group of patients with LBP, with and without radiating leg pain. Patients could be classified as acute or chronic and were evaluated at 3 weeks, 2 months, and 6 months postonset. Treatments included manipulation, drug therapy, physiotherapy, placebo, and bed rest. Acute back pain without radiation and chronic back pain responded well to manipulation; however, in none of the other groups did manipulation fare as well as other interventions (QS, 6).

Physician Consult/Medical Care/Education. Arkuszewski looked at patients with lumbosacral pain or sciatica. One group received drugs, physiotherapy, and manual examination, whereas the second added manipulation. The group receiving manipulation had a shorter treatment time and a more marked improvement. At 6-month follow-up, the manipulation group showed better neuromotor system function and a better ability to continue employment. Disability was lower in the manipulation group (QS, 18.75).

Physiologic Therapeutic Modality. Physiotherapy combined with manual manipulation and medication was examined by Arkuszewski, in contrast to the same scheme with manipulation added, as noted above. Outcomes from manipulation were better for neurologic and motor function as well as disability (QS, 18.75). Postacchini looked at patients with acute or chronic symptoms evaluated at 3 weeks, 2 months, and 6 months postonset. Manipulation was not as effective for managing the patients with radiating leg pain as the other treatment arms (QS, 6). Mathews and colleagues examined multiple treatments including manipulation, traction, sclerosant use, and epidural injections for back pain with sciatica. For patients with LBP and restricted straight leg raise test, manipulation conferred highly significant relief, more so than alternate interventions (QS, 19). Coxhead et al included among their subjects patients who had radiating pain at least to the buttocks. Interventions included traction, manipulation, exercise, and corset, using a factorial design. After 4 weeks of care, manipulation showed a significant degree of benefit on one of the scales used to assess progress. There were no real differences between groups at 4 months and 16 months posttherapy, however (QS, 25).

Exercise Modality. In the case of LBP after laminectomy, Timm reported that exercises conferred benefit both for pain relief and cost-effectiveness (QS, 25). Manipulation had only a small influence on improvement of either symptoms or function (QS, 25). In the study by Coxhead et al, radiating pain to at least the buttocks was better after 4 weeks of care for manipulation, in contrast to other treatments that disappeared 4 months and 16 months posttherapy (QS, 25).

Sham and Alternate Manual Method. Siehl looked at the use of manipulation under general anesthesia for patients with LBP and unilateral or bilateral radiating leg pain. Only temporary clinical improvement was noted when traditional electromyographic evidence of nerve root involvement was present. With negative electromyography, manipulation was reported to provide lasting improvement (QS, 31.25) Santilli and colleagues compared HVLA to soft tissue pressing without any sudden thrust in patients with moderate acute back and leg pain. The HVLA procedures were significantly more effective in reducing pain, reaching a pain-free status, and the total number of days with pain. Clinically significant differences were noted. The total number of treatment sessions was capped at 20 on a dosage of 5 times per week with care depending on pain relief. Follow-up showed relief persisting through 6 months.

Medication. Mixed acute and chronic back pain with radiation treated in a study using multiple treatment arms were evaluated at 3 weeks, 2 months, and 6 months postonset by the group of Postacchini. Medication management fared better than did manipulation when radiating leg pain was present (QS, 6). Conversely, for the work of Mathews and colleagues, the group of patients with LBP and limited straight leg raise test responded more to manipulation than to epidural steroid or sclerosants (QS, 19).

Disk Herniation

Nwuga studied 51 subjects who were having a diagnosis of prolapsed intervertebral disk and who had been referred for physical therapy. Manipulation was reported to be superior to conventional therapy (QS, 12.5). Zylbergold found that there were no statistical differences between 3 treatments�lumbar flexion exercises, home care, and manipulation. Short-term follow-up and a small sample size were posed by the author as a basis for failing to reject the null hypothesis (QS, 38).

Exercise

Exercise is one of the most well-studied forms of treatment of low back disorders. There are many different approaches to�exercise. For this report, it is important only to differentiate multidisciplinary rehabilitation. These programs are designed for patients with especially chronic condition with significant psychosocial problems. They involve trunk exercise, functional task training including work simulation/vocational training, and psychological counseling.

In a recent Cochrane review on exercise for the treatment of nonspecific LBP (QS, 82), effectiveness of exercise therapy in patients classified as acute, subacute, and chronic was compared to no treatment and alternate treatments. Outcomes included the assessment of pain, function, return to work, absenteeism, and/or global improvements. In the review, 61 trials met the inclusion criteria, most of which dealt with chronic (n = 43), whereas smaller numbers addressed acute (n = 11) and subacute (n = 6) pain. The general conclusions were as follows:

- exercise is not effective as a treatment of acute LBP,

- evidence that exercise was effective in chronic populations relative to comparisons made at follow-up periods,

- mean improvements of 13.3 points for pain and 6.9 points for function were observed, and

- there is some evidence that graded-activity exercise is effective for subacute LBP but only in the occupational setting

The review examined population and intervention characteristics, as well as outcomes to reach its conclusions. Extracting data on return to work, absenteeism, and global improvement proved so difficult that only pain and function could be quantitatively described.

Eight studies scored positively on key validity criteria. With regard to clinical relevance, many of the trials presented inadequate information, with 90% reporting the study population but only 54% adequately describing the exercise intervention. Relevant outcomes were reported in 70% of the trials.

Exercise for Acute LBP. Of the 11 trials (total n = 1192), 10 had nonexercise comparison groups. The trials presented conflicting evidence. Eight low-quality trials showed no differences between exercise and usual care or no treatment. Pooled data showed that there was no difference in shortterm pain relief between exercise and no treatment, no difference in early follow-up for pain when compared to other interventions, and no positive effect of exercise on functional outcomes.

Subacute LBP. In 6 studies (total n = 881), 7 exercise groups had a nonexercise comparison group. The trials offered mixed results with regard to evidence of effectiveness, with fair evidence of effectiveness for a graded-exercise activity program as the only notable finding. Pooled data did not show evidence to either support or refute the use of exercise for subacute LBP, either for decreasing pain or improving function.

Chronic LBP. There were 43 trials included in this group (total n = 3907). Thirty-three of the studies had nonexercise comparison groups. Exercise was at least as effective as other conservative interventions for LBP, and 2 high-quality studies and 9 lower-quality studies found exercise to be more effective. These studies used individualized exercise programs, focusing mainly on strengthening or trunk stabilization. There were 14 trials that found no difference between exercise and other conservative interventions; of these, 2 were rated highly and 12 rated lower. Pooling the data showed a mean improvement of 10.2 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.31-19.09) points on a 100-mm pain scale for exercise compared to no treatment and 5.93 (95% CI, 2.21- 9.65) points compared to other conservative treatments. Functional outcomes also showed improvements as follows: 3.0 points at earliest follow-up compared to no treatment (95% CI, ?0.53 to 6.48) and 2.37 points (95% CI, 1.04-3.94) compared to other conservative treatments.

Indirect subgroup analysis found that trials examining health care study populations had higher mean improvements in pain and physical functioning compared to their comparison groups or to trials set in occupational or general populations.

The review authors offered the following conclusions:

- In acute LBP, exercises are not more effective than other conservative interventions. Meta-analysis showed no advantage over no treatment of pain and functional outcomes over the short or long-term.

- There is fair evidence of effectiveness of a gradedactivity exercise program in subacute LBP in occupational settings. The effectiveness for other types of exercise therapy in other populations is unclear.

- In chronic LBP, there is good evidence that exercise is at least as effective as other conservative treatments. Individually designed strengthening or stabilizing programs appear to be effective in health care settings. Meta-analysis found functional outcomes significantly improved; however, the effects were very small, with a less than 3-point (of 100) difference between the exercise and comparison groups at earliest follow-up. Pain outcomes were also significantly improved in groups receiving exercises relative to other comparisons, with a mean of approximately 7 points. Effects were similar over longer follow-up, though confidence intervals increased. Mean improvements in pain and functioning may be clinically meaningful in studies from health care populations in which improvements were significantly greater than those observed in studies from general or mixed populations.

The Danish group review of exercise was able to identify 5 systematic reviews and 12 guidelines that discussed exercise for acute LBP, 1 systematic review and 12 guidelines for subacute, and 7 systematic reviews and 11 guidelines for chronic. Furthermore, they identified 1 systematic review that selectively evaluated for postsurgical�cases. Conclusions were essentially the same as the Cochrane review, with the exceptions that there was limited support for McKenzie maneuvers for patients with acute condition and for intensive rehabilitation programs for 4 to 6 weeks after disk surgery over light exercise programs.

Natural and Treatment History for LBP

Most studies have demonstrated that nearly half of LBP will improve within 1 week, whereas nearly 90% of it will be gone by 12 weeks. Even more, Dixon demonstrated that perhaps as much as 90% of LBP will resolve on its own, without any intervention whatsoever. Von Korff demonstrated that a significant number of patients with acute LBP will have persistent pain if they are observed up to 2 years.

Phillips found that nearly 4 of 10 people will have LBP after an episode at 6 months from onset, even if the original pain has disappeared because more than 6 in 10 will have at least 1 relapse during the first year after an episode. These initial relapses occur within 8 weeks most commonly and may reoccur over time, though in decreasing percentages.

Workers’ compensation injury patients were observed for 1 year to examine symptom severity and work status. Half of those studied lost no work time in the first month after injury, but 30% did lose time from work due to their injury over the course of 1 year. Of those who missed work in the first month due to their injury and had already been able to return to work, nearly 20% had absence later in that same year. This implies that assessing return to work at 1 month after injury will fail to give an honest depiction of the chronic, episodic nature of LBP. Although many patients have returned to work, they will later experience continuing problems and work-related absences. Impairment present at more than 12 weeks postinjury may be far higher than what has been previously reported in the literature, where rates of 10% are common. In fact, the rates may go up to 3 to 4 times higher.

In a study by Schiotzz-Christensen and colleagues, the following was noted. In relation to sick leave, LBP has a favorable prognosis, with a 50% return to work within the first 8 days and only 2% on sick leave after 1 year. However, 15% had been on sick leave during the following year and about half continued to complain of discomfort. This suggested that an acute episode of LBP significant enough to cause the patient to seek a visit to a general practitioner is followed by a longer period of low-grade disability than previously reported. Also, even for those who returned to work, up to 16% indicated that they were not functionally improved. In another study looking at outcomes after 4 weeks after initial diagnosis and treatment, only 28% of patients did not experience any pain. More strikingly, the persistence of pain differed between groups that had radiating pain and those that did not, with 65% of the former feeling improvement at 4 weeks, vs 82% of the latter. The general findings from this study differ from others in that 72% of patients still experienced pain 4 weeks after initial diagnosis.

Hestbaek and colleagues reviewed a number of articles in a systematic review. The results showed that the reported proportion of patients who still experienced pain after 12 months after onset was 62% on average, with 16% sick-listed 6 months after onset, and with 60% experiencing relapse of work absence. Also, they found that the mean reported prevalence of LBP in patients who had past episodes of LBP was 56%, compared to just 22% for those who had no such history. Croft and colleagues performed a prospective study looking at the outcomes of LBP in general practice, finding that 90% of patients with LBP in primary care had stopped consulting with symptoms within 3 months; however, most were still experiencing LBP and disability 1 year after the initial visit. Only 25% had fully recovered within that same year.

There are even different results in the study by Wahlgren et al. Here, most patients continued to experience pain at both 6 and 12 months (78% and 72%, respectively). Only 20% of the sample had fully recovered by 6 months and only 22% by 12 months.

Von Korff has provided a lengthy list of data he considers relevant to assessing the clinical course of back pain as follows: age, sex, race/ethnicity, years of education, occupation, change in occupation, employment status, disability insurance status, litigation status, recency/age at first onset of back pain, recency/age when care was sought, recency of back pain episode, duration of current/most recent episode of back pain, number of back pain days, current pain intensity, average pain intensity, worst pain intensity, ratings of interference with activities, activity limitation days, clinical diagnosis for this episode, bed rest days, work loss days, recency of back pain flare-up, and duration of the most recent flare-up.

In a practice-based observational study by Haas et al of almost 3000 patients with acute and chronic condition treated by chiropractors and primary care medical doctors, pain was noted in patients with acute and chronic condition up to 48 months after enrollment. At 36 months, 45% to 75% of patients reported at least 30 days of pain in the prior year, and 19% to 27% of patients with chronic condition recalled daily pain over the previous year.

The variability noted in these and many other studies can be explained in part by the difficulty in making an adequate diagnosis, by the different classification schemes used in classifying LBP, by the different outcome tools used in each study and by many other factors. It also points up the extreme difficulty in getting a handle on the day-to-day reality for those who have LBP.

Common Markers and Rating Complexity for LBP

What Are the Relevant Benchmarks for Evaluating Process of Care?. One benchmark is described above, that being natural history. Complexity and risk stratification are important, as�are cost issues; however, cost-effectiveness is beyond the scope of this report.

It is understood that patients with uncomplicated LBP improve faster than those with various complications, the most notable of which is radiating pain. Many factors may influence the course of back pain, including comorbidity, ergonomic factors, age, the level of fitness of the patient, environmental factors, and psychosocial factors. The latter is receiving a great deal of attention in the literature, though as noted elsewhere in this book, such consideration may not be justified. Any of these factors, alone or in combination, may hamper or retard the recovery period after injury.

It seems that biomechanical factors play an important role in the incidence of first-time episodes of LBP and its attendant problems such as work loss; psychosocial factors come into play more in subsequent episodes of LBP. The biomechanical factors can lead to tissue tearing, which then create pain and limited ability for years to follow. This tissue damage cannot be seen on standard imaging and may only be apparent upon dissection or surgery.

Risk factors for LBP include the following:

- age, sex, severity of symptoms;

- increased spinal flexibility, decreased muscle endurance;

- prior recent injury or surgery;

- abnormal joint motion or decreased body mechanics;

- prolonged static posture or poor motor control;

- work-related such as vehicle operation, sustained loads, materials handling;

- employment history and satisfaction; and

- wage status.

IJzelenberg and Burdorf investigated whether demographic, work-related physical, or psychosocial risk factors involved in the occurrence of musculoskeletal conditions determine subsequent health care use and sick leave. They found that within 6 months, nearly one third of industrial workers with LBP (or neck and upper extremity problems) had a recurrence of sick leave for that same problem and a 40% recurrence of health care use. Work-related factors associated with musculoskeletal symptoms were similar to those associated with health care use and sick leave; but, for LBP, older age and living alone strongly determined whether patients with these problems took any sick leave. The 12- month prevalence of LBP was 52%, and of those with symptoms at baseline, 68% had a recurrence of the LBP. Jarvik and colleagues add depression as an important predictor of new LBP. They found the use of MRI to be a less important predictor of LBP than depression.

What Are the Relevant Outcome Measures?. The Clinical Practice Guidelines formulated by the Canadian Chiropractic Association and the Canadian Federation of Chiropractic Regulatory Boards note that there are a number of outcomes that may be used to demonstrate change as a result of treatment. These should be both reliable and valid. According to the Canadian guidelines, appropriate standards are useful in chiropractic practice because they are able to perform the following:

- consistently evaluate the effects of care over time;

- help indicate the point of maximum therapeutic improvement;

- uncover problems related to care such as noncompliance;

- document improvement to the patient, doctor, and third parties;

- suggest modifications of the goals of treatment if necessary;

- quantify the clinical experience of the doctor;

- justify the type, dose, and duration of care;

- help provide a database for research; and

- assist in establishing standards of treatment of specific conditions.

The broad general classes of outcomes include functional outcomes, patient perception outcomes, physiologic outcomes, general health assessments, and subluxation syndrome outcomes. This chapter addresses only functional and patient perception outcomes assessed by questionnaires and functional outcomes assessed by manual procedures.

Functional Outcomes. These are outcomes that measure the patient’s limitations in going about his or her normal daily activities. What is being looked at is the effect of a condition or disorder on the patient (ie, LBP, for which a specific diagnosis may not be present or possible) and its outcome of care. Many such outcome tools exist. Some of the better known include the following:

- Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire,

- Oswestry Disability Questionnaire,

- Pain Disability Index,

- Neck Disability Index,

- Waddell Disability Index, and

- Million Disability Questionnaire.

These are only some of the existing tools for assessing function.

In the existing RCT literature for LBP, functional outcomes have been shown to be the outcome that demonstrates the greatest change and improvement with SMT. Activities of daily living, along with patient selfreporting of pain, were the 2 most notable outcomes to show such improvement. Other outcomes fared less well, including trunk range of motion (ROM) and straight leg raise.

In the chiropractic literature, the outcome inventories used most frequently for LBP are the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire and the Oswestry Questionnaire. In a study in 1992, Hsieh found that both tools provided consistent results over the course of his trial, although the results from the 2 questionnaires differed.

Patient Perception Outcomes. Another important set of outcomes involve patient perception of pain and their satisfaction with care. The first involves measuring changes in pain perception over time of its intensity, duration, and frequency. There are a number of valid tools available that can accomplish this, including the following:

Visual analog scale�this is a 10-cm line that has pain descriptions noted at both ends of that line representing no pain to intolerable pain; the patient is asked to mark a point on that line that reflects their perceived pain intensity. There are a number of variants for this outcome, including the Numerical Rating Scale (where the patient provides a number between 0 and 10 to represent the amount of pain they have) and the use of pain levels from 0 to 10 depicted pictorially in boxes, which the patient may check. All of these appear to be equally reliable, but for ease of use, either the standard VAS or Numerical Rating Scale is commonly used.

Pain diary�these may be used to help monitor a variety of different pain variables (for example, frequency, which the VAS cannot measure). Different forms may be used to collect this information, but it is typically completed on a daily basis.

McGill Pain Questionnaire�this scale helps quantify several psychologic components of pain as follows: cognitive-evaluative, motivational-affective, and sensory discriminative. In this instrument, there are 20 categories of words that describe the quality of pain. From the results, 6 different pain variables can be determined.

All of the above instruments have been used at various times to monitor the progress of treatment of back pain with SMT.

Patient satisfaction addresses both the effectiveness of care as well as the method of receiving that care. There are numerous methods of assessing patient satisfaction, and not all of them were designed to be specifically used for LBP or for manipulation. However, Deyo did develop one for use with LBP. His instrument examines the effectiveness of care, information, and caring. There is also the Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire, which assesses 8 separate indices (such as efficacy/outcomes or professional skill, for example). Cherkin noted that the Visit Specific Satisfaction Questionnaire can be used for chiropractic outcome assessment.

Recent work has shown that patient confidence and satisfaction with care are related to outcomes. Seferlis found that patients were more satisfied and felt that they were provided better explanations about their pain from practitioners who used manual therapy. Regardless of treatment, highly satisfied patients at 4 weeks were more likely than less satisfied patients to perceive greater pain improvement throughout 18-month follow-up in a study by Hurwitz et al. Goldstein and Morgenstern found a weak association between treatment confidence in the therapy they received and greater improvement in LBP. A frequent assertion is that benefits observed from application of manipulation methods are a result of physician attention and touching. Studies directly testing this hypothesis were conducted by Hadler et al in patients with acute condition and by Triano et al in patients with subacute and chronic condition. Both studies compared manipulation to a placebo control. In the study of Hadler, the control balanced for provider time attention and frequency, whereas Triano et al also added an education program with home exercise recommendations. In both cases, results demonstrated that although attention given to patients was associated with improvement over time, patients receiving manipulation procedures improved more quickly.

General Health Outcome Measures. This has traditionally been a difficult outcome to effectively measure but a number of more recent instruments are demonstrating that it can be done reliably. The 2 major instruments for doing so are the Sickness Impact Profile and the SF-36. The first assesses dimensions such as mobility, ambulation, rest, work, social interaction, and so on; the second looks primarily at well being, functional status, and overall health, as well as 8 other health concepts, to ultimately determine 8 indices that can be used to determine overall health status. Items here include physical functioning, social functioning, mental health, and others. This tool has been used in many settings and has also been adapted into shorter forms as well.

Physiologic Outcome Measures. The chiropractic profession has a number of physiologic outcomes that are used with regard to the patient care decision-making process. These include such procedures as ROM testing, muscle function testing, palpation, radiography, and other less common procedures (leg length analysis, thermography, and others). This chapter addresses only the physiologic outcomes assessed manually.

Range of Motion. This examination procedure is used by nearly every chiropractor and is used to assess impairment because it is related to spinal function. It is possible to use ROM as a means to monitor improvement in function over time and, therefore, improvement as it relates to the use of SMT. One can assess regional and global lumbar motion, for example, and use that as one marker for improvement.

Range of motion can be measured via a number of different means. One can use standard goniometers, inclinometers, and more sophisticated tools that require the use of specialized equipment and computers. When doing so, it is important to consider the reliability of each individual method. A number of studies have assessed various devices as follows:

- Zachman found the use of the rangiometer moderately reliable,

- Nansel found that using 5 repeated measures of cervical spine motion with an inclinometer to be reliable,

- Liebenson found that the modified Schrober technique, along with inclinometers and flexible spinal rulers had the best support from the literature,

- Triano and Schultz found that ROM for the trunk, along with trunk strength ratios and myoelectrical activity, was good indicator for LBP disability, and

- a number of studies found that the kinematic measurement of ROM for spinal mobility is reliable.

Muscle Function. Evaluating muscle function may be done using an automated system or by manual means. Although manual muscle testing has been a common diagnostic practice within the chiropractic profession, there are few studies demonstrating clinical reliability for the procedure, and these are not considered to be of high quality.

Automated systems are more reliable and are capable of assessing muscle parameters such as strength, power, endurance, and work, as well as assess different modes of muscle contraction (isotonic, isometric, isokinetic). Hsieh found that a patient-initiated method worked well for specific muscles, and other studies have shown the dynamometer to have good reliability.

Leg Length Inequality. Very few studies of leg length have shown acceptable levels of reliability. The best methods for assessing reliability and validity of leg length involve radiographic means and are therefore subject to exposure to ionizing radiation. Finally, the procedure has not been studied as to validity, making the use of this as an outcome questionable.

Soft Tissue Compliance. Compliance is assessed by both manual and mechanical means, using the hand alone or using a device such as an algometer. By assessing compliance, the chiropractor is looking to assess muscle tone.

Early tests of compliance by Lawson demonstrated good reliability. Fisher found increases in tissue compliance with subjects involved in physical therapy. Waldorf found that prone segmental tissue compliance had good test/retest variation of less than 10%.

Pain tolerance assessed using these means has been found reliable, and Vernon found it was a useful measure in assessing the cervical paraspinal musculature after adjusting. The guidelines group from the Canadian Chiropractic Association and the Canadian Federation of Chiropractic Regulatory Boards concluded that �the assessments are safe and inexpensive and appear to be responsive to conditions and treatments commonly seen in chiropractic practice.�

Conclusion

Existing research evidence regarding the usefulness of spinal adjusting/manipulation/mobilization indicates the following:

- As much or more evidence exists for the use of SMT to reduce symptoms and improve function in patients with chronic LBP as for use in acute and subacute LBP.

- Use of exercise in conjunction with manipulation is likely to speed and improve outcomes as well as minimize episodic recurrence.

- There was less evidence for the use of manipulation for patients with LBP and radiating leg pain, sciatica, or radiculopathy.

- Cases with high severity of symptoms may benefit by referral for comanagement of symptomswith medication.

- There was little evidence for the use of manipulation for other conditions affecting the low back and very few articles to support a higher rating.

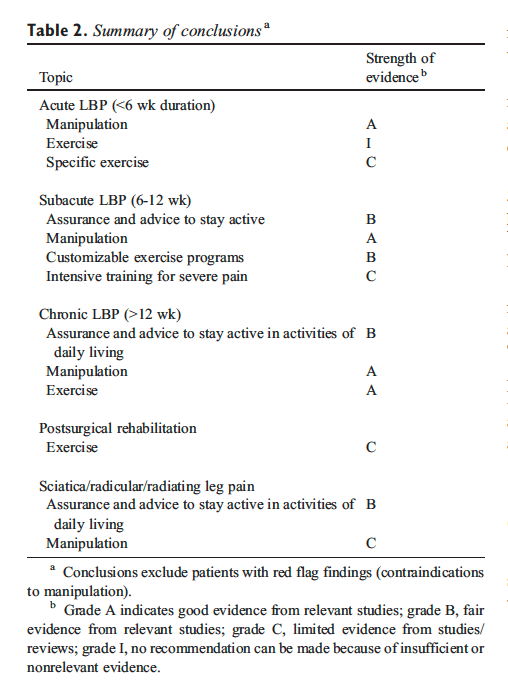

Exercise and reassurance have been shown to be of value primarily in chronic LBP and low back problems associated with radicular symptoms. A number of standardized, validated tools are available to help capture meaningful clinical improvement over the course of low back care. Typically, functional improvement (as opposed to simple reported reduction in pain levels) may be clinically meaningful for monitoring responses to care. The literature reviewed remains relatively limited in predicting responses to care, tailoring specific combinations of intervention regimens (although the combination of manipulation and exercise may be better than exercise alone), or formulating condition-specific recommendations for frequency and�duration of interventions. Table 2 summarizes the recommendations of the team, based on the review of the evidence.

Practical Applications

- Evidence exists for the use of spinal manipulation to reduce symptoms and improve function in patients with chronic, acute, and subacute LBP.

- Exercise in conjunction with manipulation is likely to speed and improve outcomes and minimize recurrence

In conclusion,�more evidence-based research studies have become available regarding the effectiveness of chiropractic care for low back pain and sciatica. The article also demonstrated that exercise should be used together with chiropractic to help speed up the rehabilitation process and further improve recovery. In most cases, chiropractic care can be used for the management of low back pain and sciatica, without the need for surgical interventions. However, if surgery is required to achieve recovery, a chiropractor may refer the patient to the next best healthcare professional. Information referenced from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic as well as to spinal injuries and conditions. To discuss the subject matter, please feel free to ask Dr. Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

Curated by Dr. Alex Jimenez

Additional Topics: Sciatica

Sciatica is referred to as a collection of symptoms rather than a single type of injury or condition. The symptoms are characterized as radiating pain, numbness and tingling sensations from the sciatic nerve in the lower back, down the buttocks and thighs and through one or both legs and into the feet. Sciatica is commonly the result of irritation, inflammation or compression of the largest nerve in the human body, generally due to a herniated disc or bone spur.

IMPORTANT TOPIC: EXTRA EXTRA: Treating Sciatica Pain

Blank

References

- Leape, LL, Park, RE, Kahan, JP, and Brook, RH. Group judgments of appropriateness: the effect of panel composition. Qual Assur Health Care. 1992; 4: 151�159

- Bigos S, Bowyer O, Braen G, et al. Acute low back problems in adults. Rockville (Md): Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service, U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services; 1994.

- National Health and Medical Research Council. A guide to the development, implementation and evaluation of clinical practice guidelines. AusInfo, Canberra, Australia; 1999

- McDonald, WP, Durkin, K, and Pfefer, M. How chiropractors think and practice: the survey of North American Chiropractors. Semin Integr Med. 2004; 2: 92�98

- Christensen, M, Kerkoff, D, Kollasch, ML, and Cohen, L. Job analysis of chiropractic. National Board of Chiropractic Examiners, Greely (Colo); 2000

- Christensen, M, Kollasch, M, Ward, R, Webb, K, Day, A, and ZumBrunnen, J. Job analysis of chiropractic. NBCE, Greeley (Colo); 2005

- Hurwitz, E, Coulter, ID, Adams, A, Genovese, BJ, and Shekelle, P. Use of chiropractic services from 1985 through 1991 in the United States and Canada. Am J Public Health. 1998; 88: 771�776

- Coulter, ID, Hurwitz, E, Adams, AH, Genovese, BJ, Hays, R, and Shekelle, P. Patients using chiropractors in North America. Who are they, and why are they in chiropractic care?. Spine. 2002; 27: 291�296

- Coulter, ID and Shekelle, P. Chiropractic in North America: a descriptive analysis. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005; 28: 83�89

- Bombadier, C, Bouter, L, Bronfort, G, de Bie, R, Deyo, R, Guillemin, F, Kreder, H, Shekelle, P, van Tulder, MW, Waddell, G, and Weinstein, J. Back Group. in: The Cochrane Library, Issue 1. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester, UK; 2004

- Bombardier, C, Hayden, J, and Beaton, DE. Minimal clinically important difference. Low back pain: outcome measures. J Rheumatol. 2001; 28: 431�438

- Bronfort, G, Haas, M, Evans, RL, and Bouter, LM. Efficacy of spinal manipulation and mobilization for low back pain and neck pain: a systematic review and best evidence synthesis. Spine J. 2004; 4: 335�356

- Petrie, JC, Grimshaw, JM, and Bryson, A. The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network Initiative: getting validated guidelines into local practice. Health Bull (Edinb). 1995; 53: 345�348

- Cluzeau, FA and Littlejohns, P. Appraising clinical practice guidelines in England and Wales: the development of a methodologic framework and its application to policy. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1999; 25: 514�521

- Stroup, DF, Berlin, JA, Morton, SC et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000; 283: 2008�2012

- Shekelle, P, Morton, S, Maglione, M et al. Ephedra and ephedrine for weight loss and athletic performance enhancement: clinical efficacy and side effects. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 76 [Prepared by Southern California Evidence-based Practice Center, RAND, under contract no. 290-97-0001, Task Order No. 9]. AHRQ Publication No. 03-E022. Agency for Health Care Research and Quality, Rockville (Md); 2003

- van Tulder, MW, Koes, BW, and Bouter, LM. Conservative treatment of acute and chronic nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials of the most common interventions. Spine. 1997; 22: 2128�2156

- Hagen, KB, Hilde, G, Jamtvedt, G, and Winnem, M. Bed rest for acute low back pain and sciatica (Cochrane Review). in: The Cochrane Library. vol. 2. Update Software, Oxford; 2000

- (L�ndesmerter og kiropraktik. Et dansk evidensbaseret kvalitetssikringsprojekt)in: Danish Society of Chiropractic and Clinical Biomechanics (Ed.) Low back pain and Chiropractic. A Danish evidence-based quality assurance project report. 3rd ed.�Danish Society of Chiropractic and Clinical Biomechanics, Denmark; 2006

- Hilde, G, Hagen, KB, Jamtvedt, G, and Winnem, M. Advice to stay active as a single treatment for low back pain and sciatica. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002; : CD003632

- Waddell, G, Feder, G, and Lewis, M. Systematic reviews of bed rest and advice to stay active for acute low back pain. Br J Gen Pract. 1997; 47: 647�652

- Assendelft, WJ, Morton, SC, Yu, EI, Suttorp, MJ, and Shekelle, PG. Spinal manipulative therapy for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004; : CD000447

- Hurwitz, EL, Morgenstern, H, Harber, P et al. Second prize: the effectiveness of physical modalities among patients with low back pain randomized to chiropractic care: findings from the UCLA low back pain study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2002; 25: 10�20

- Hsieh, CY, Phillips, RB, Adams, AH, and Pope, MH. Functional outcomes of low back pain: comparison of four treatment groups in a randomized clinical trial. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1992; 15: 4�9

- Cherkin, DC, Deyo, RA, Battie, M, Street, J, and Barlow, W. A comparison of physical therapy, chiropractic manipulation, and provision of an educational booklet for low back pain. N Engl J Med. 1998; 339: 1021�1029

- Meade, TW, Dyer, S, Browne, W, Townsend, J, and Frank, AO. Low back pain of mechanical origin: randomized comparison of chiropractic and hospital outpatient treatment. Br Med J. 1990; 300: 1431�1437

- Meade, TW, Dyer, S, Browne, W, and Frank, AO. Randomized comparison of chiropractic and hospital outpatient management for low back pain: results from extended follow-up. Br Med J. 1995; 311: 349�351

- Doran, DM and Newell, DJ. Manipulation in treatment of low back pain: a multicentre study. Br Med J. 1975; 2: 161�164

- Seferlis, T, Nemeth, G, Carlsson, AM, and Gillstrom, P. Conservative treatment in patients sick-listed for acute low-back pain: a prospective randomized study with 12 months’ follow up. Eur Spine J. 1998; 7: 461�470

- Wand, BM, Bird, C, McAuley, JH, Dore, CJ, MacDowell, M, and De Souza, L. Early intervention for the management of acute low back pain. Spine. 2004; 29: 2350�2356

- Hurley, DA, McDonough, SM, Dempster, M, Moore, AP, and Baxter, GD. A randomized clinical trial of manipulative therapy and interferential therapy for acute low back pain. Spine. 2004; 29: 2207�2216

- Godfrey, CM, Morgan, PP, and Schatzker, J. A randomized trail of manipulation for low back pain in a medical setting. Spine. 1984; 9: 301�304

- Rasmussen, GG. Manipulation in the treatment of low back pain (-a randomized clinical trial). Man Medizin. 1979; 1: 8�10

- Hadler, NM, Curtis, P, Gillings, DB, and Stinnett, S. A benefit of spinal manipulation as adjunctive therapy for acute low-back pain: a stratified controlled trial. Spine. 1987; 12: 703�706

- Hadler, NM, Curtis, P, Gillings, DB, and Stinnett, S. Der nutzen van manipulationen als zusatzliche therapie bei akuten lumbalgien: eine gruppenkontrollierte studie. Man Med. 1990; 28: 2�6

- Erhard, RE, Delitto, A, and Cibulka, MT. Relative effectiveness of an extension program and a combined program of manipulation and flexion and extension exercises in patients with acute low back syndromes. Phys Ther. 1994; 174: 1093�1100

- von Buerger, AA. A controlled trial of rotational manipulation in low back pain. Man Medizin. 1980; 2: 17�26

- Gemmell, H and Jacobson, BH. The immediate effect of Activator vs. Meric adjustment on acute low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1995; 18: 5453�5456

- MacDonald, R and Bell, CMJ. An open controlled assessment of osteopathic manipulation in nonspecific low-back pain. Spine. 1990; 15: 364�370

- Hoehler, FK, Tobis, JS, and Buerger, AA. Spinal manipulation for low back pain. JAMA. 1981; 245: 1835�1838

- Coyer, AB and Curwen, IHM. Low back pain treated by manipulation: a controlled series. Br Med J. 1955; : 705�707

- Waterworth, RF and Hunter, IA. An open study of diflunisal, conservative and manipulative therapy in the management of acute mechanical low back pain. N Z Med J. 1985; 98: 372�375

- Blomberg, S, Hallin, G, Grann, K, Berg, E, and Sennerby, U. Manual therapy with steroid injections- a new approach to treatment of low back pain: a controlled multicenter trial with an evaluation by orthopedic surgeons. Spine. 1994; 19: 569�577

- Bronfort, G. Chiropractic versus general medical treatment of low back pain: a small scale controlled clinical trial. Am J Chiropr Med. 1989; 2: 145�150

- Grunnesjo, MI, Bogefledt, JP, Svardsudd, KF, and Blomberg, SIE. A randomized controlled clinical trial of stay-active care versus manual therapy in addition to stay-active care: functional variables and pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2004; 27: 431�441

- Pope, MH, Phillips, RB, Haugh, LD, Hsieh, CY, MacDonald, L, and Haldeman, S. A prospective, randomized three-week trial of spinal manipulation, transcutaneous muscle stimulation, massage and corset in the treatment of subacute low back pain. Spine. 1994; 19: 2571�2577

- Sims-Williams, H, Jayson, MIV, Young, SMS, Baddeley, H, and Collins, E. Controlled trial of mobilization and manipulation for patients with low back pain in general practice. Br Med J. 1978; 1: 1338�1340

- Sims-Williams, H, Jayson, MIV, Young, SMS, Baddeley, H, and Collins, E. Controlled trial of mobilization and manipulation for low back pain: hospital patients. Br Med J. 1979; 2: 1318�1320

- Skargren, EI, Carlsson, PG, and Oberg, BE. One-year follow-up comparison of the cost and effectiveness of chiropractic and physiotherapy as primary management for back pain: subgroup analysis, recurrent, and additional health care utilization. Spine. 1998; 23: 1875�1884

- Hoiriis, KT, Pfleger, B, McDuffie, FC, Cotsonis, G, Elsnagak, O, Hinson, R, and Verzosa, GT. A randomized trial comparing chiropractic adjustments to muscle relaxants for subacute low back pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2004; 27: 388�398

- Andersson, GBJ, Lucente, T, Davis, AM, Kappler, RE, Lipton, JA, and Leurgens, S. A comparison of osteopathic spinal manipulation with standard care for patients with low back pain. N Engl J Med. 1999; 341: 1426�1431

- Aure, OF, Nilsen, JH, and Vasseljen, O. Manual therapy and exercise therapy in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. Spine. 2003; 28: 525�538

- Niemisto, L, Lahtinen-Suopanki, T, Rissanen, P, Lindgren, KA, Sarno, S, and Hurri, H. A randomized trial of combined manipulation, stabilizing exercises, and physical consultation compared to physician consultation alone for chronic low back pain. Spine. 2003; 28: 2185�2191

- Koes, BW, Bouter, LM, van Mameren, H, Essers, AHM, Verstegen, GMJR, Hafhuizen, DM, Houben, JP, and Knipschild, P. A blinded randomized clinical trial of manual therapy and physiotherapy for chronic back and neck complaints: physical outcome measures. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1992; 15: 16�23

- Koes, BW, Bouter, LM, van mameren, H, Essers, AHM, Verstegen, GJMG, Hofhuizen, DM, Houben, JP, and Knipschild, PG. A randomized trial of manual therapy and physiotherapy for persistent back and neck complaints: subgroup analysis and relationship between outcome measures. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1993; 16: 211�219

- Koes, BM, Bouter, LM, van Mameren, H, Essers, AHM, Verstegen, GMJR, hofhuizen, DM, Houben, JP, and Knipschild, PG. Randomized clinical trial of manipulative therapy and physiotherapy for persistent back and neck complaints: results of a one-year follow-up. Br Med J. 1992; 304: 601�605

- Rupert, R, Wagnon, R, Thompson, P, and Ezzeldin, MT. Chiropractic adjustments: results of a controlled clinical trial in Egypt. ICA Int Rev Chir. 1985; : 58�60

- Triano, JJ, McGregor, M, Hondras, MA, and Brennan, PC. Manipulative therapy versus education programs in chronic low back pain. Spine. 1995; 20: 948�955

- Gibson, T, Grahame, R, Harkness, J, Woo, P, Blagrave, P, and Hills, R. Controlled comparison of short-wave diathermy treatment with osteopathic treatment in non-specific low back pain. Lancet. 1985; 1: 1258�1261

- Koes, BW, Bouter, LM, van Mameren, H, Essers, AHM, Verstegen, GMJR, Hofhuizen, DM, Houben, JP, and Knipschild, PG. The effectiveness of manual therapy, physiotherapy, and treatment by the general practitioner for nonspecific back and neck complaints: a randomized clinical trial. Spine. 1992; 17: 28�35

- Mathews, JA, Mills, SB, Jenkins, VM, Grimes, SM, Morkel, MJ, Mathews, W, Scott, SM, and Sittampalam, Y. Back pain and sciatica: controlled trials of manipulation, traction, sclerosant and epidural injections. Br J Rheumatol. 1987; 26: 416�423

- Hemilla, HM, Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi, S, Levoska, S, and Puska, P. Long-term effectiveness of bone-setting, light exercise therapy, and physiotherapy for prolonged back pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2002; 25: 99�104

- Hemilla, HM, Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi, S, Levoska, S, and Puska, P. Does folk medicine work? A randomized clinical trial on patients with prolonged back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997; 78: 571�577

- Coxhead, CE, Inskip, H, Meade, TW, North, WR, and Troup, JD. Multicentre trial of physiotherapy in the management of sciatic symptoms. Lancet. 1981; 1: 1065�1068

- Herzog, W, Conway, PJ, and Willcox, BJ. Effects of different treatment modalities on gait symmetry and clinical measurements for sacroiliac joint patients. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1991; 14: 104�109