Metabolic Syndrome And Chiropractic

Metabolic Syndrome:

Key indexing terms:

- Metabolic syndrome X

- Insulin resistance

- Hyperglycemia

- Inflammation

- Weight loss

Abstract

Objective: This article presents an overview of metabolic syndrome (MetS), which is a collection of risk factors that can lead to diabetes, stroke, and heart disease. The purposes of this article are to describe the current literature on the etiology and pathophysiology of insulin resistance as it relates to MetS and to suggest strategies for dietary and supplemental management in chiropractic practice.

Methods: The literature was searched in PubMed, Google Scholar, and the Web site of the American Heart Association, from the earliest date possible to May 2014. Review articles were identified that outlined pathophysiology of MetS and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and relationships among diet, supplements, and glycemic regulation, MetS, T2DM, and musculoskeletal pain.

Results: Metabolic syndrome has been linked to increased risk of developing T2DM and cardiovascular disease and increased risk of stroke and myocardial infarction. Insulin resistance is linked to musculoskeletal complaints both through chronic inflammation and the effects of advanced glycosylation end products. Although diabetes and cardiovascular disease are the most well-known diseases that can result from MetS, an emerging body of evidence demonstrates that common musculoskeletal pain syndromes can be caused by MetS.

Conclusions: This article provides an overview of lifestyle management of MetS that can be undertaken by doctors of chiropractic by means of dietary modification and nutritional support to promote blood sugar regulation.

Introduction: Metabolic Syndrome

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) has been described as a cluster of physical examination and laboratory findings�that directly increases the risk of degenerative metabolic disease expression. Excess visceral adipose tissue, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension are conditions that significantly contribute to the syndrome. These conditions are united by a pathophysiological basis in low-grade chronic inflammation and increase an individual’s risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and all-cause mortality.1

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003-2006 estimated that approximately 34% of United States adults aged 20 years and more had MetS.2 The same NHANES data found that 53% had abdominal adiposity, a condition that is closely linked to visceral adipose stores. Excess visceral adiposity generates increased systemic levels of pro-inflammatory mediator molecules. Chronic, low- grade inflammation has been well documented as an associated and potentially inciting factor for the development of insulin resistance and T2DM.1

NHANES 2003-2006 data showed that 39% of subjects met criteria for insulin resistance. Insulin resistance is a component of MetS that significantly contributes to the expression of chronic, low-grade inflammation and predicts T2DM expression. T2DM costs the United States in excess of $174 billion in 2007. 3 It is estimated that 1 in 4 adults will have T2DM by the year 2050.3 Currently, more than one third of US adults (34.9%) are obese, 4 and, in 2008, the annual medical cost of obesity was $147 billion.4,5 This clearly represents a health care concern.

The pervasiveness of MetS dictates that doctors of chiropractic will see a growing proportion of patients who fit the syndrome criteria.6 Chiropractic is most commonly used for musculoskeletal complaints believed to be mechanical in nature;6 however, an emerging body of evidence identifies MetS as a biochemical promoter of musculoskeletal complaints such as neck pain, shoulder pain, patella tendinopathy, and widespread musculoskeletal pain. 7�13 As an example, the cross-linking of collagen fibers can be caused by increased advanced glycation end-product (AGE) formation as seen in insulin resistance.14 Increased collagen cross-linking is observed in both osteoarthritis and degenerative disc disease, 15 and reduced mobility in elderly patients with T2DM has also been attributed to AGE-induced collagen cross-linking. 16,17

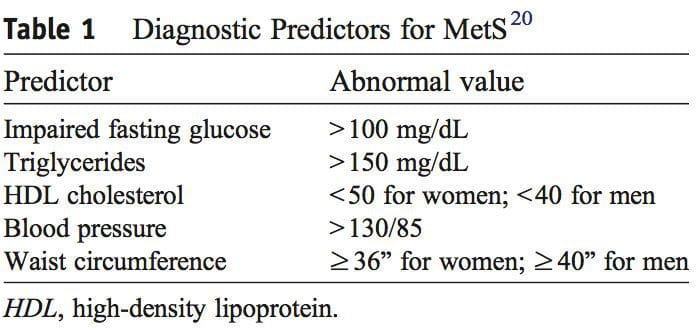

A diagnosis of MetS is made from a patient having 3 of the 5 findings presented in Table 1. Fasting hyperglycemia is termed impaired fasting glucose and indicates insulin resistance. 18,19 An elevated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level measures long-term blood glucose�regulation and is diagnostic for T2DM when elevated in the presence of impaired fasting glucose. 3,18

The emerging evidence demonstrates that we cannot view musculoskeletal pain as only coming from conditions that are purely mechanical in nature. Doctors of chiropractic must demonstrate prowess in identification and management of MetS and an understanding of insulin resistance as its main pathophysiological feature. The purposes of this article are to describe the current literature on the etiology and pathophysiology of insulin resistance as it relates to MetS and to suggest strategies for dietary and supplemental management in chiropractic practice.

Methods

PubMed was searched from the earliest possible date to May 2014 to identify review articles that outlined the pathophysiology of MetS and T2DM. This led to further search refinements to identify inflammatory mechanisms that occur in the pancreas, adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, and hypothalamus. Searches were also refined to identify relationships among diet, supplements, and glycemic regulation. Both animal and human studies were reviewed. The selection of specific supplements was based on those that were most commonly used in the clinical setting, namely, gymnema sylvestre, vanadium, chromium and ?-lipoic acid.

PubMed was searched from the earliest possible date to May 2014 to identify review articles that outlined the pathophysiology of MetS and T2DM. This led to further search refinements to identify inflammatory mechanisms that occur in the pancreas, adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, and hypothalamus. Searches were also refined to identify relationships among diet, supplements, and glycemic regulation. Both animal and human studies were reviewed. The selection of specific supplements was based on those that were most commonly used in the clinical setting, namely, gymnema sylvestre, vanadium, chromium and ?-lipoic acid.

Discussion

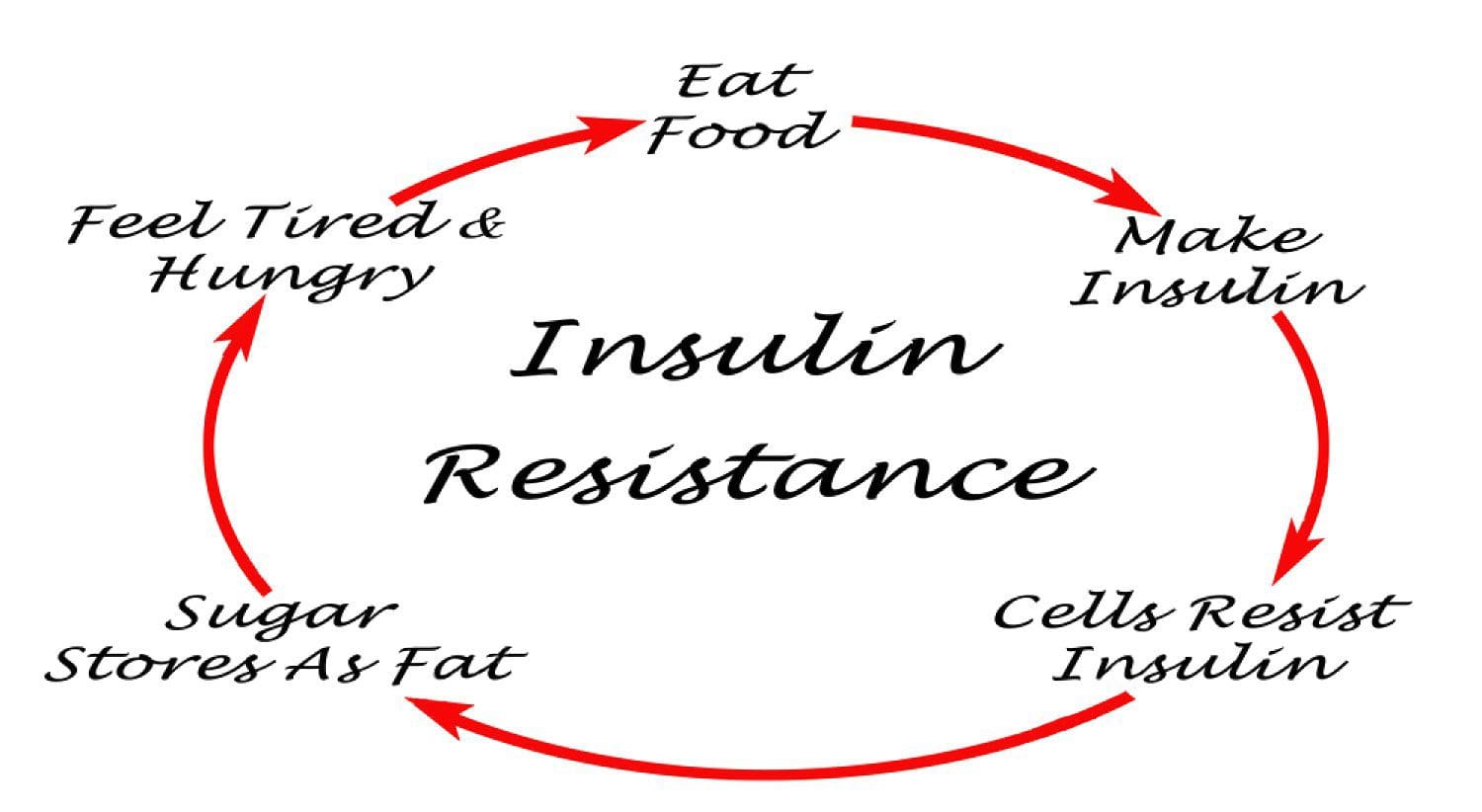

Insulin Resistance Overview

Under normal conditions, skeletal muscle, hepatic, and adipose tissues require the action of insulin for cellular glucose entry. Insulin resistance represents an inability of insulin to signal glucose passage into insulin-dependent cells. Although a genetic predisposition can exist, the�etiology of insulin resistance has been linked to chronic low-grade inflammation.1 Combined with insulin resistance-induced hyperglycemia, chronic low-grade inflammation also sustains MetS pathophysiology.1

Under normal conditions, skeletal muscle, hepatic, and adipose tissues require the action of insulin for cellular glucose entry. Insulin resistance represents an inability of insulin to signal glucose passage into insulin-dependent cells. Although a genetic predisposition can exist, the�etiology of insulin resistance has been linked to chronic low-grade inflammation.1 Combined with insulin resistance-induced hyperglycemia, chronic low-grade inflammation also sustains MetS pathophysiology.1

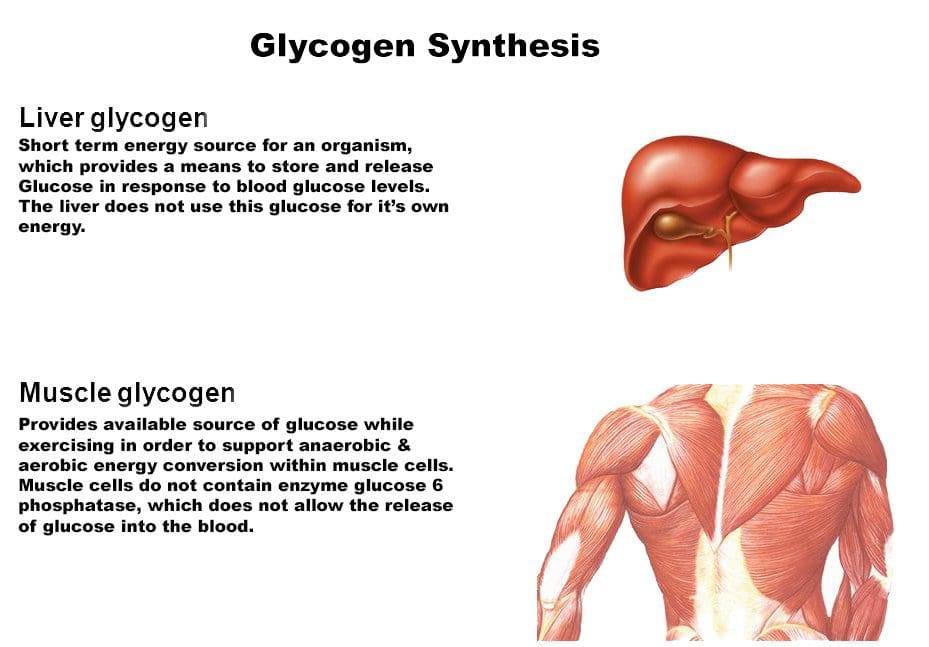

Two thirds of postprandial blood glucose metabolism occurs within skeletal muscle via an insulin-dependent mechanism.18,19 Insulin binding to its receptor triggers glucose entry and subsequently inhibits lipolysis within the target tissue.21,22 Glucose enters skeletal muscles cells by way of a glucose transporter designated Glut4. 18 Owing to genetic variability, insulin-mediated glucose uptake can vary more than 6-fold among non-diabetic individuals. 23

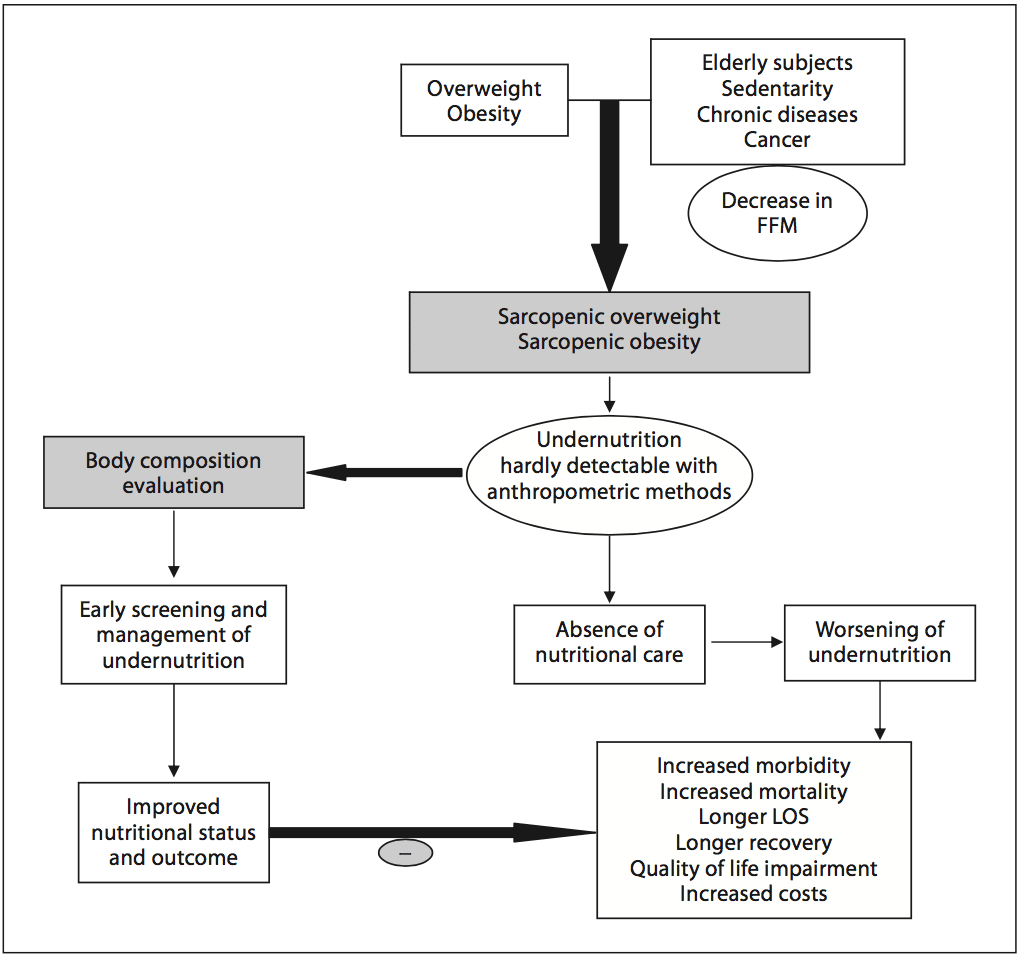

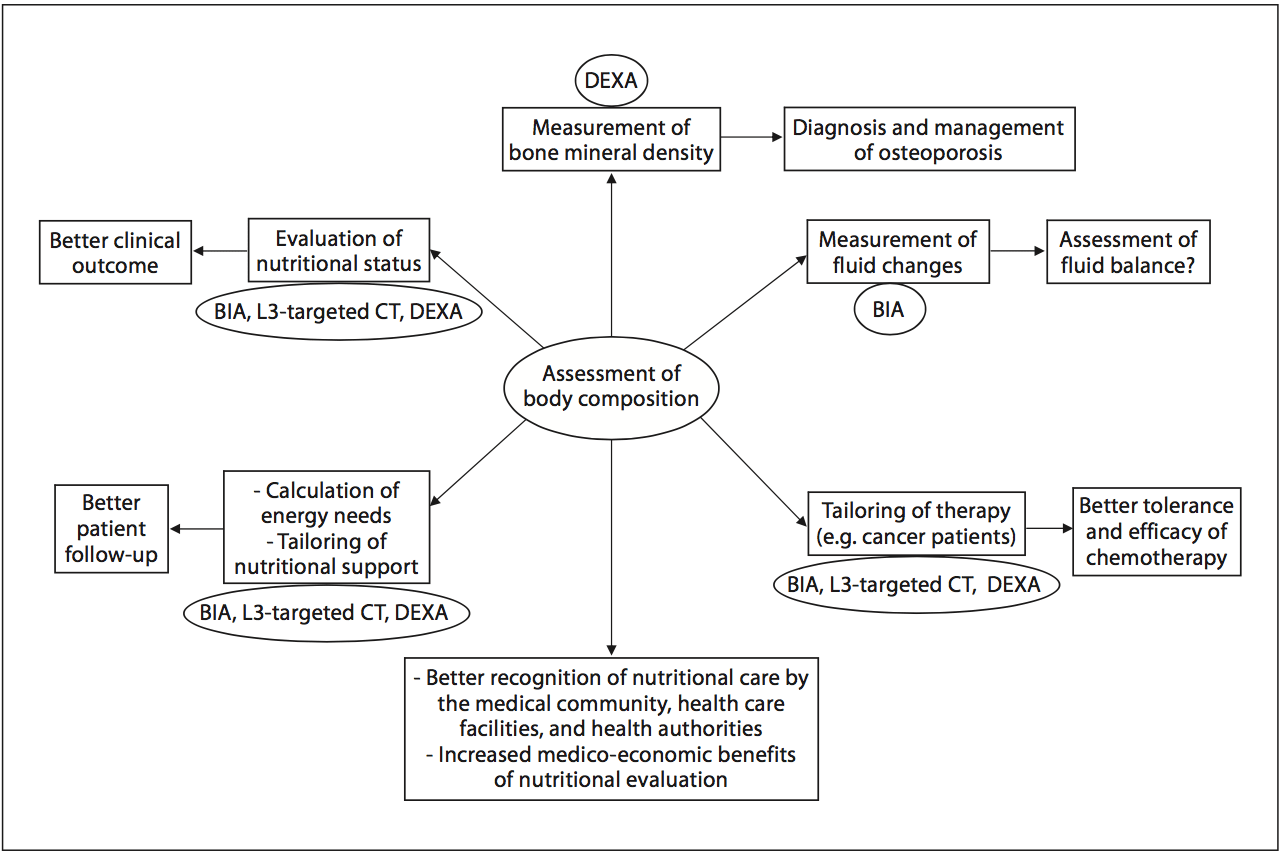

Prolonged insulin resistance leads to structural changes within skeletal muscle such as decreased Glut4 transporter number, intramyocellular fat accu- mulation, and a reduction in mitochondrial con- tent.19,24 These events are thought to impact energy generation and functioning of affected skeletal mus- cle.24 Insulin-resistant skeletal muscle is less able to suppress lipolysis in response to insulin binding.25 Subsequently, saturated free fatty acids accumulate and generate oxidative stress. 22 The same phenomenon within adipose tissue generates a rapid adipose cell expansion and tissue hypoxia.26 Both these processes increase inflammatory pathway activation and the generation of proinflammatory cytokines (PICs).27

Multiple inflammatory mediators are associated with the promotion of skeletal muscle insulin resistance. The PICs tumor necrosis factor ? (TNF-?), interleukin 1 (IL- 1), and IL-6 have received much attention because of their direct inhibition of insulin signaling.28�30 Since cytokine testing is not performed clinically, elevated levels of high- sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) best represent the low-grade systemic inflammation that characterizes insulin resistance.31,32

Insulin resistance�induced hyperglycemia can lead to irreversible changes in protein structure, termed glycation, and the formation of AGEs. Cells such as those of the vascular endothelium are most vulnerable to hyperglycemia due to utilization of an insulin-independent Glut1 transporter. 33 This makes AGE generation responsible for most diabetic complications, 15,33,34 including collagen cross-linking.15

If unchanged, prolonged insulin resistance can lead to T2DM expression. The relationship between chronic low-grade inflammation and T2DM has been well characterized. 35 Research has demonstrated that patients with T2DM also have chronic inflammation within the pancreas, termed insulitis, and it worsens hyperglycemia due to the progressive loss of insulin- producing ? cells.36�39

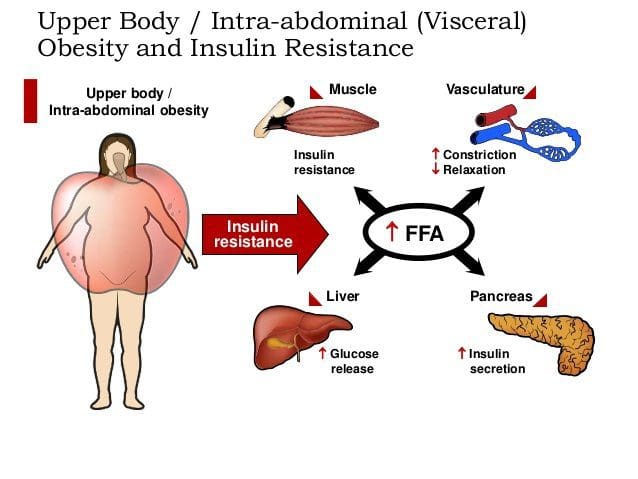

Visceral Adiposity And Insulin Resistance

Caloric excess and a sedentary lifestyle contribute to the accumulation of subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue. Adipose tissue was once thought of as a metabolically inert passive energy depot. A large body of evidence now demonstrates that excess visceral adipose tissue acts as a driver of chronic low-grade inflammation and insulin resistance.27,34

Caloric excess and a sedentary lifestyle contribute to the accumulation of subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue. Adipose tissue was once thought of as a metabolically inert passive energy depot. A large body of evidence now demonstrates that excess visceral adipose tissue acts as a driver of chronic low-grade inflammation and insulin resistance.27,34

It has been documented that immune cells infiltrate rapidly expanding visceral adipose tissue. 26,40 Infil- trated macrophages become activated and release PICs that ultimately cause a phenotypic shift in resident macrophage phenotype to a classic inflammatory M1 profile.27 This vicious cycle creates a chronic inflam- matory response within adipose tissue and decreases the production of adipose-derived anti-inflammatory cytokines.43 As an example, adiponectin is an adipose- derived anti-inflammatory cytokine. Macrophage- invaded adipose tissue produces less adiponectin, and this has been correlated with increasing insulin resistance. 26

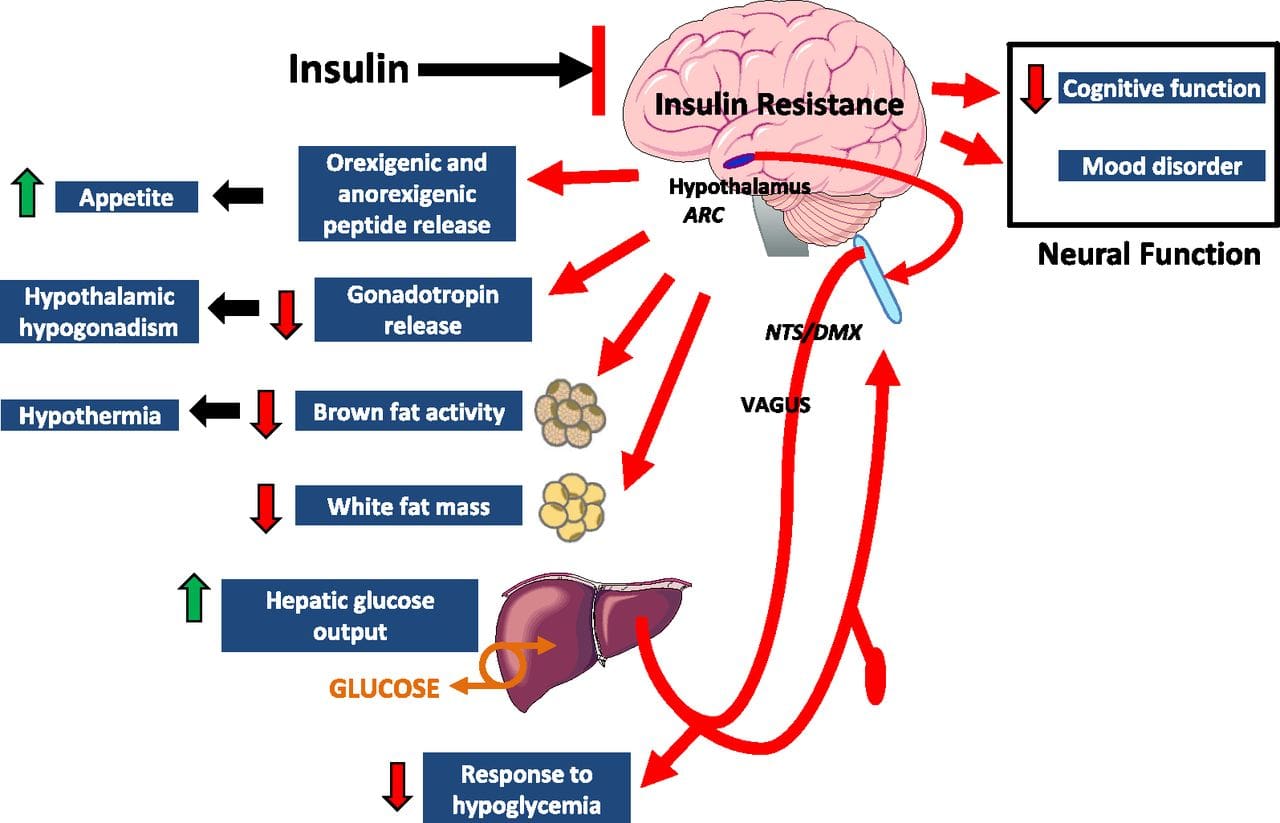

Hypothalamic Inflammation And Insulin Resistance

Eating behavior in the obese and overweight has been popularly attributed to a lack of will power or genetics. However, recent research has demonstrated a link between hypothalamic inflammation and increased body weight.41,41

Eating behavior in the obese and overweight has been popularly attributed to a lack of will power or genetics. However, recent research has demonstrated a link between hypothalamic inflammation and increased body weight.41,41

Centers that govern energy balance and glucose homeostasis are located within the hypothalamus. Recent studies demonstrate that inflammation in the hypothalamus coincides with metabolic inflammation and an increase in appetite.43 These hypothalamic centers simultaneously become resistant to anorexigenic stimuli, leading to altered energy intake. It has been suggested that this provides a neuropathological basis for MetS and drives a progressive increase in body weight. 41

Central metabolic inflammation pathologically activates hypothalamic immune cells and disrupts central insulin and leptin signaling.41 Peripherally, this has been associated with dysregulated glucose homeostasis that also impairs pancreatic ? cell functioning.41,44 Hypothalamic inflammation contributes to hypertension through similar mechanisms, and it is thought that central inflammation parallels chronic low-grade systemic inflammation and insulin resistance.41�44

Clinical Correlates Diet-Induced Inflammation & Insulin Resistance

Feeding generally leads to a short-term increase in both oxidative stress and inflammation. 41 Total�calories consumed, glycemic index, and fatty acid profile of a meal all influence the degree of postprandial inflammation. It is estimated that the average American consumes approximately 20% of calories from refined sugar, 20% from refined grains and flour, 15% to 20% from excessively fatty meat products, and 20% from refined seed/legume oils.45 This pattern of eating contains a macronutrient composition and glycemic index that promote hyperglycemia, hyperlipemia, and an acute postprandial inflammatory response. 46 Collectively referred to as postprandial dysmetabolism, this pro-inflammatory response can sustain levels of chronic low-grade inflammation that leads to excess body fat, coronary heart disease (CHD), insulin resistance, and T2DM.28,29,47

Feeding generally leads to a short-term increase in both oxidative stress and inflammation. 41 Total�calories consumed, glycemic index, and fatty acid profile of a meal all influence the degree of postprandial inflammation. It is estimated that the average American consumes approximately 20% of calories from refined sugar, 20% from refined grains and flour, 15% to 20% from excessively fatty meat products, and 20% from refined seed/legume oils.45 This pattern of eating contains a macronutrient composition and glycemic index that promote hyperglycemia, hyperlipemia, and an acute postprandial inflammatory response. 46 Collectively referred to as postprandial dysmetabolism, this pro-inflammatory response can sustain levels of chronic low-grade inflammation that leads to excess body fat, coronary heart disease (CHD), insulin resistance, and T2DM.28,29,47

Recent evidence suggests that several MetS criteria may not sufficiently identify all individuals with postprandial dysmetabolism. 48,49 A 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (2-h OGTT) result greater than 200 mg/dL can be used clinically to diagnose T2DM. Although MetS includes a fasting blood glucose level less than 100 mg/dL, population studies have shown that a fasting glucose as low as 90 mg/dL can be associated with an 2-h OGTT level greater than 200 mg/dL.49 Further, a recent large cohort study indicated that an increased 2-h OGTT was independently predictive of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in a nondiabetic population. 48 Mounting evidence indicates that post- prandial glucose levels are better correlated with MetS and predicting future cardiovascular events than fasting blood glucose alone.41,48

Fasting triglyceride levels generally correlate with postprandial levels, and a fasting triglyceride level greater than 150 mg/dL reflects MetS and insulin resistance. Contrastingly, epidemiologic data indicate that a fasting triglyceride level greater than 100 mg/dL influences CHD risk via postprandial dysmetabolism. 48 The acute postprandial inflammatory response that contributes to CHD risk includes an increase in PICs, free radicals, and hsCRP.48,49 These levels are not measured clinically but, monitoring fasting glucose, 2-hour postprandial glucose and fasting triglycerides can be used as correlates of postprandial dysmetabolic and low-grade systemic inflammation.

MetS And Disease Expression

Diagnosis of MetS has been linked to an increased risk of developing T2DM and cardiovascular disease over the following 5 to 10 years. 1 It further increases a patient’s risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, and death from any of the aforementioned conditions.1

Diagnosis of MetS has been linked to an increased risk of developing T2DM and cardiovascular disease over the following 5 to 10 years. 1 It further increases a patient’s risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, and death from any of the aforementioned conditions.1

Facchini et al47 followed 208 apparently healthy, non-obese subjects for 4 to 11 years while monitoring the incidence of clinical events such as hypertension, stroke, CHD, cancer, and T2DM. Approximately one fifth of participants experienced clinical events, and all of these subjects were either classified as intermediately or severely insulin resistant. It is important to note that all of these clinical events have a pathological basis in chronic low-grade inflammation,50 and no events were experienced in the insulin-sensitive groupings. 47

Insulin resistance is linked to musculoskeletal com- plaints both through chronic inflammation and the effects of AGEs. Advanced glycation end-products have been shown to extensively accumulate in osteoarthritic cartilage and treatment of human chondrocytes with AGEs increased their catabolic activity. 51 Advanced glycation end-products increase collagen stiffness via cross-linking and likely contribute to reduced joint mobility seen in elderly patients with T2DM.52 Com- pared to non-diabetics, type II diabetic patients are known to have altered proteoglycan metabolism in their intervertebral discs. This altered metabolism may pro- mote weakening of the annular fibers and subsequently, disc herniation.53 The presence of T2DM increases a person’s risk of expressing disc herniation in both the cervical and lumbar spines.17,54 Patients with T2DM are also more likely to develop lumbar stenosis compared with non-diabetics, and this has been documented as a plausible relationship between MetS risk factors and physician-diagnosed lumbar disc herniation. 55�57

There are no specific symptoms that denote early skeletal muscle structural changes. Fatty infiltration and decreased muscle mitochondria content are observed within age-related sarcopenia 58 ; however, it is still being argued whether fatty infiltration is a risk factor for low back pain. 59,60

Clinical management of MetS should be geared toward improving insulin sensitivity and reducing chronic low-grade inflammation. 1 Regular exercise without weight loss is associated with reduced insulin resistance, and at least 30 minutes of aerobic activity and resistance training is recommended daily. 61,62 Although frequently considered preventative, exercise, dietary, and weight loss interventions should be considered alongside pharmacological management in those with MetS. 1

Data regarding the exact amount of weight loss needed to improve chronic inflammation are inconclusive. In overweight individuals without diagnosed MetS, a very-low-carbohydrate diet (b 10% calories from carbohydrate) has significantly reduced plasma inflammatory markers (TNF-?, hsCRP, and IL-6) with�as little as 6% reduction in body weight.63,64 Individuals who meet MetS criteria may require 10% to 20% body weight loss to reduce inflammatory markers. 65 Interestingly, the Mediterranean Diet has been shown to reduce markers of systemic inflammation independent of weight loss65 and was recommended in the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association Adult Treatment Panel 4 guidelines.66

A growing body of research has examined the effects of the Spanish ketogenic Mediterranean diet, including olive oil, green vegetables and salads, fish as the primary protein, and moderate red wine consumption. In a sample of 22 patients, adoption of the Spanish ketogenic Mediterranean diet with 9 g of supplemental salmon oil on days when fish was not consumed has led to complete resolution of MetS.67 Significant reductions in markers of chronic systemic inflammation were seen in 31 patients following this diet for 12 weeks.68

A Paleolithic diet based on lean meat, fish, fruits, vegetables, root vegetables, eggs, and nuts has been described as more satiating per calorie than a diabetes diet in patients with T2DM.69 In a randomized crossover study, a Paleolithic diet resulted in lower mean HbA1c values, triglycerides, diastolic blood pressure, waist circumference, improved glucose tolerance, and higher high-density lipoprotein (HDL) values compared to a diabetes diet.70 Within the context of these changes, a referral for medication management may be advisable.

Irrespective of name, a low-glycemic diet that focuses on vegetables, fruits, lean meats, omega-3 fish, nuts, and tubers can be considered anti-inflammatory and has been shown to ameliorate insulin resistance. 49,71�73 Inflammatory markers and insulin resistance further improve when weight loss coincides with adherence to an anti-inflammatory diet.70 A growing body of evidence suggests that specific supplemental nutrients also reduce insulin resistance and improve chronic low-grade inflammation.

Key Nutrients That Promote Insulin Sensitivity

Research has identified nutrients that play key roles in promoting proper insulin sensitivity, including vitamin D, magnesium, omega-3 (n-3) fatty acids, curcumin, gymnema, vanadium, chromium, and ?-lipoic acid. It is possible to get adequate vitamin D from sun exposure and adequate amounts of magnesium and omega-3 fatty acids from food. Contrastingly, the therapeutic levels of chromium and ?-lipoic acid that affect insulin sensitivity and reduce�insulin resistance cannot be obtained in food and must be supplemented.

Research has identified nutrients that play key roles in promoting proper insulin sensitivity, including vitamin D, magnesium, omega-3 (n-3) fatty acids, curcumin, gymnema, vanadium, chromium, and ?-lipoic acid. It is possible to get adequate vitamin D from sun exposure and adequate amounts of magnesium and omega-3 fatty acids from food. Contrastingly, the therapeutic levels of chromium and ?-lipoic acid that affect insulin sensitivity and reduce�insulin resistance cannot be obtained in food and must be supplemented.

Vitamin D, Magnesium, Omega-3 Fatty Acids, & Curcumin

Vitamin D, magnesium, and n-3 fatty acids have multiple functions, and generalized inflammation reduction is a common mechanism of action.74�80 Their supplemental use should be considered in the context of low-grade inflammation reduction and health promotion, rather than as a specific treatment for MetS or T2DM.

Vitamin D, magnesium, and n-3 fatty acids have multiple functions, and generalized inflammation reduction is a common mechanism of action.74�80 Their supplemental use should be considered in the context of low-grade inflammation reduction and health promotion, rather than as a specific treatment for MetS or T2DM.

Evidence pertaining to the precise role of vitamin D in MetS and insulin resistance is inconclusive. Increas- ing dietary and supplemental vitamin D intake in young men and women may lower the risk of MetS and T2DM development,81 and a low serum vitamin D level has been associated with insulin resistance and T2DM expression. 82 Supplementation to improve low serum vitamin D (reference range, 32-100 ng/mL) is effective, but its impact on improving central glycemia and insulin sensitivity is conflicting. 83 Treating insulin resistance and MetS with vitamin D as a monotherapy appears to be unsuccessful. 82,83 Achieving normal vitamin D blood levels through adequate sun exposure and/or supplementation is advised for general health. 84�86

The average American diet commonly contains a low magnesium intake.80 Recent studies suggest that supple- mental magnesium can improve insulin sensitivity. 81,82 Taking 365 mg/d may be effective in reducing fasting glucose and raising HDL cholesterol in T2DM,83 as well as normomagnesemic, overweight, nondiabetics. 84

Diets high in the omega-6 fat linoleic acid have been associated with insulin resistance85 and higher levels of serum pro-inflammatory mediator markers including IL-6, IL-1?, TNF-?, and hsCRP.87 Supplementation to increase dietary omega-3 fatty acids at the expense of omega-6 fatty acids has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity. 88�90 Six months of omega-3 supplementation at 3 g/d with meals has been shown to reduce MetS markers including fasting triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, and an increase in anti-inflammatory adiponectin. 91

Curcumin is responsible for the yellow pigmentation of the spice turmeric. Its biological effects can be characterized as antidiabetic and antiobesity via down- regulating TNF-?, suppressing nuclear factor ?B activation, adipocytokine expression, and leptin level modulation,. 92�95 Curcumin has been reported to activate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-?, the nuclear target of the thiazolidinedione class of antidiabetic drugs,93 and it also protects hepatic and pancreatic cells. 92,93 Numerous studies have reported�weight loss, hsCRP reduction, and improved insulin sensitivity after curcumin supplementation.92�95

There is no established upper limit for curcumin, and doses of up to 12 g/d are safe and tolerable in humans. 96 A randomized, double-blinded, placebo- controlled trial (N = 240) showed a reduced progression of prediabetes to T2DM after 9 months of 1500 mg/d curcumin supplementation.97

Curcumin, 98 vitamin D, 84 magnesium, 91 and omega-3 fatty acids80 are advocated as daily supplements to promote general health. A growing body of evidence supports the views of Gymnema sylvestre, vanadium, chromium, and ?-lipoic acid should as therapeutic supplements to assist in glucose homeostasis.

G Sylvestre

Gymnemic acids are the active component of the G sylvestre plant leaves. Gymnemic acids are the active component of the G sylvestre plant leaves. Studies evaluating G sylvestre’s effects on diabetes in humans have generally been of poor methodological quality. Experimental animal studies have found that gymnemic acids may decrease glucose uptake in the small intestine, inhibit gluconeogenesis, and reduce hepatic and skeletal muscle insulin resistance.99 Other animal studies suggest that gymnemic acids may have comparable efficacy in reducing blood sugar levels to the first-generation sulfonylurea, tolbutamide.100

Gymnemic acids are the active component of the G sylvestre plant leaves. Gymnemic acids are the active component of the G sylvestre plant leaves. Studies evaluating G sylvestre’s effects on diabetes in humans have generally been of poor methodological quality. Experimental animal studies have found that gymnemic acids may decrease glucose uptake in the small intestine, inhibit gluconeogenesis, and reduce hepatic and skeletal muscle insulin resistance.99 Other animal studies suggest that gymnemic acids may have comparable efficacy in reducing blood sugar levels to the first-generation sulfonylurea, tolbutamide.100

Evidence from open-label trials suggests its use as a supplement to oral antidiabetic hypoglycemic agents. 96 One quarter of patients were able to discontinue their drug and maintain normal glucose levels on an ethanolic gymnema extract alone. Although the evidence to date suggests its use in humans and animals is safe and well tolerated, higher quality human studies are warranted.

Vanadyl Sulfate

Vanadyl sulfate has been reported to prolong the events of insulin signaling and may actually improve insulin sensitivity.101 Limited data suggest that it inhibits gluconeogenesis, possibly ameliorating hepatic insulin resistance. 100,101 Uncontrolled clinical trials have reported improvements in insulin sensitivity using 50 to 300 mg daily for periods ranging from 3 to 6 weeks. 101�103 Contrastingly, a recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial found that 50 mg of vanadyl sulfate twice daily for 4 weeks had no effect in individuals with impaired glucose tolerance. 104 Limited clinical and experimental data exist supporting the use of vanadyl sulfate to improve insulin resistance,�and further research is warranted regarding its safety and efficacy.

Vanadyl sulfate has been reported to prolong the events of insulin signaling and may actually improve insulin sensitivity.101 Limited data suggest that it inhibits gluconeogenesis, possibly ameliorating hepatic insulin resistance. 100,101 Uncontrolled clinical trials have reported improvements in insulin sensitivity using 50 to 300 mg daily for periods ranging from 3 to 6 weeks. 101�103 Contrastingly, a recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial found that 50 mg of vanadyl sulfate twice daily for 4 weeks had no effect in individuals with impaired glucose tolerance. 104 Limited clinical and experimental data exist supporting the use of vanadyl sulfate to improve insulin resistance,�and further research is warranted regarding its safety and efficacy.

Chromium

Diets high in refined sugar and flour are deficient in chromium (Cr) and lead to an increased urinary excretion of chromium. 105,106 The progression of MetS is not likely caused by a chromium deficiency, 107 and dosages that benefit glycemic regulation are not achievable through food. 106,108,109

Diets high in refined sugar and flour are deficient in chromium (Cr) and lead to an increased urinary excretion of chromium. 105,106 The progression of MetS is not likely caused by a chromium deficiency, 107 and dosages that benefit glycemic regulation are not achievable through food. 106,108,109

A recent randomize, double-blind trial demonstrated that 1000 ?g Cr per day for 8 months improved insulin sensitivity by 10% in subjects with T2DM.110 Cefalu et al110 further suggested that these improvements might be more applicable to patients with a greater degree of insulin resistance, impaired fasting plasma glucose, and higher HbA1c values. Chromium’s mechanism of action for improving insulin sensitivity is through increased Glut4 translocation via prolonging insulin receptor signaling.109 Chromium has been well tolerated at 1000 ?g/d,105 and animal models using significantly more than 1000 ? Cr per day were not associated with toxicological consequences.109

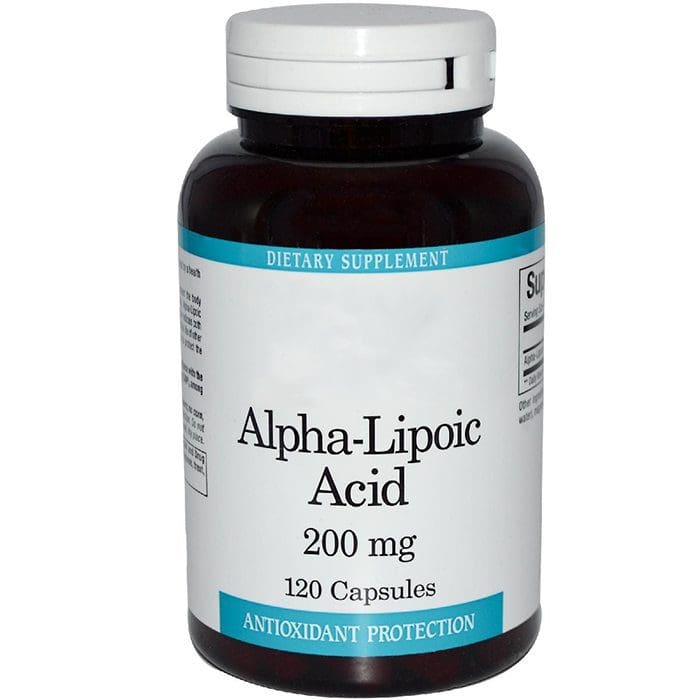

?-Lipoic Acid

Humans derive ?-lipoic acid through dietary means and from endogenous synthesis. 111 The foods richest in ?-lipoic acid are animal tissues with extensive metabolic activity such as animal heart, liver, and kidney, which are not consumed in large amounts in the typical American diet. 111 Supplemental amounts of ?-lipoic acid used in the treatment of T2DM (300-600 mg) are likely to be as much as 1000 times greater than the amounts that could be obtained from the diet.112

Humans derive ?-lipoic acid through dietary means and from endogenous synthesis. 111 The foods richest in ?-lipoic acid are animal tissues with extensive metabolic activity such as animal heart, liver, and kidney, which are not consumed in large amounts in the typical American diet. 111 Supplemental amounts of ?-lipoic acid used in the treatment of T2DM (300-600 mg) are likely to be as much as 1000 times greater than the amounts that could be obtained from the diet.112

Lipoic acid synthase (LASY) appears to be the key enzyme involved in the generation of endogenous lipoic acid, and obese mice with diabetes have reduced LASY expression when compared with age-and sex- matched controls.111 In vitro studies to identify potential inhibitors of lipoic acid synthesis suggest a role for diet-induced hyperglycemia and the PIC TNF- ? in the down-regulation of LASY.113 The inflammatory basis of insulin resistance may therefore drive lowered levels of endogenous lipoic acid via reducing the activity of LASY.

?-Lipoic acid has been found to act as insulin mimetic via stimulating Glut4-mediated glucose trans- port in muscle cells. 110,114?-Lipoic acid is a lipophilic free radical scavenger and may affect glucose homeostasis through protecting the insulin receptor from damage114 and indirectly via decreasing nuclear factor ?B�mediated TNF-? and IL-1 production. 110 In�postmenopausal women with MetS (presence of at least 3 ATPIII clinical criteria) 4 g/d of a combined inositol and ?-lipoic acid supplement for 6 months significantly improved OGTT scores by 20% in two thirds of the subjects. 114 A recent randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled study showed that 300 mg/d ?- lipoic acid for 90 days significantly decreased HbA1c values in subjects with T2DM.115

Side effects to ?-lipoic acid supplementation as high as 1800 mg/d have largely been limited to nausea. 116 It may be best to take supplemental ?-lipoic acid on an empty stomach (1 hour before or 2 hours after eating) because food intake reportedly reduces its bioavailability.117 Clinicians should be aware that ?-lipoic acid supplementation might increase the risk of hypoglycemia in diabetic patients using insulin or oral antidiabetic agents.117

Limitations

This is a narrative overview of the topic of MetS. A systematic review was not performed; therefore, there may be relevant information missing from this review. The contents of this overview focuses on the opinions of the authors, and therefore, others may disagree with our opinions or approaches to management. This overview is limited by the studies that have been published. To date, no studies have been published that identify the effectiveness of a combination of a dietary intervention, such as the Spanish ketogenic diet, and nutritional supplementation on the expression of the MetS. Similarly, this approach has not been studied in patients with musculoskeletal pain who also have the MetS. Consequently, the information presented in this article is speculative. Longitudinal studies are needed before any specific recommendations can be made for patients with musculoskeletal that may be influenced by the MetS.

This is a narrative overview of the topic of MetS. A systematic review was not performed; therefore, there may be relevant information missing from this review. The contents of this overview focuses on the opinions of the authors, and therefore, others may disagree with our opinions or approaches to management. This overview is limited by the studies that have been published. To date, no studies have been published that identify the effectiveness of a combination of a dietary intervention, such as the Spanish ketogenic diet, and nutritional supplementation on the expression of the MetS. Similarly, this approach has not been studied in patients with musculoskeletal pain who also have the MetS. Consequently, the information presented in this article is speculative. Longitudinal studies are needed before any specific recommendations can be made for patients with musculoskeletal that may be influenced by the MetS.

Conclusion: Metabolic Syndrome

This overview suggests that MetS and type 2 diabetes are complex conditions, and their prevalence is expected to increase substantially in the coming years. Thus, it is important to identify if the MetS may be present in patients who are nonresponsive to manual care and to help predict who may not respond adequately.

We suggest that diet and exercise are essential to managing these conditions, which can be supported with key nutrients, such as vitamin D, magnesium, and�omega-3 fatty acids. We also suggest that curcumin, G sylvestre, vanadyl sulfate chromium, and ?-lipoic acid could be viewed as specific nutrients that may be taken during the process of restoring appropriate insulin sensitivity and signaling.

Chiropractic Care

David R. Seaman DC, MS,?, Adam D. Palombo DC

Professor, Department of Clinical Sciences, National University of Health Sciences, Pinellas Park, FL Private Chiropractic Practice, Newburyport, MA

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

No funding sources were reported for this study. David Seaman is a paid consultant for Anabolic Laboratories, a manufacturer of nutritional products for health care professionals. Adam Palombo was sponsored and remunerated by Anabolic laboratories to speak at chiropractic conventions/meetings.

Blank

References:

1. Kaur J. A comprehensive review on metabolic syndrome.<br />

Cardiol Res Pract 2014:943162, http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/<br />

2014/943162.<br />

2. Ford ES, Giles WH, Dietz WH. Prevalence of the metabolic<br />

syndrome among US adults. Findings from the Third National<br />

Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Am Med Assoc<br />

2006;287:356�9.<br />

3. Boyle JP, Thompson TJ, Gregg EW, Barker LE, Williamson<br />

DF. Projection of the year 2050 burden of diabetes in the US<br />

adult population: dynamic modeling of incidence, mortality,<br />

and prediabetes prevalence. Popul Health Metr 2010;8:29,<br />

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1478-7954-8-29.<br />

4. [Internet]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.<br />

Adult Obesity Facts. Atlanta: CDC; 2014. [Available from<br />http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html].<br />

5. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of<br />

childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011�2012.<br />

JAMA 2014;311(8):806�14.<br />

6. Riksman JS, Williamson OD, Walker BF. Delineating<br />

inflammatory and mechanical sub-types of low back pain: a<br />

pilot survey of fifty low back pain patients in a chiropractic<br />

setting. Chiropr Man Therap 2011;19(1):5, http://dx.doi.org/<br />

10.1186/2045-709X-19-5.<br />

7. Dobretsov M, Ghaleb AH, Romanovsky D, Pablo CS, Stimers<br />

JR. Impaired insulin signaling as a potential trigger of<br />

pain in diabetes and prediabetes. Int Anesthesiol Clin<br />

2007;45(2):95�105.<br />

8. Mantyselka P, Miettola J, Niskanen L, Kumpusalo E. Glucose<br />

regulation and chronic pain at multiple sites. Rheumatology<br />

2008;47(8):1235�8.<br />

9. M�ntyselk� P, Miettola J, Niskanen L, Kumpusalo E.<br />

Persistent pain at multiple sites�connection to glucose<br />

derangement. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2009;84(2):e30�2.<br />

10. Mantyselka P, Kautianen H, Vanhala M. Prevalence of neck<br />

pain in subjects with metabolic syndrome�a cross-sectional<br />

population-based study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2010;11:<br />

171, http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-11-171.<br />

11. Rechardt M, Shiri R, Karppinen J, Jula A, Heli�vaara M,<br />

Viikari-Juntura E. Lifestyle and metabolic factors in relation<br />

to shoulder pain and rotator cuff tendinitis: a population-based<br />

study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2010;11:165.<br />

12. Gaida JE, Alfredson L, Kiss ZS, Wilson AM, Alfredson H,<br />

Cook JL. Dyslipidemia in Achilles tendinopathy is<br />

characteristic of insulin resistance. Med Sci Sports Exerc<br />

2009;41:1194�7.<br />

13. Malliaras P, Cook JL, Kent PM. Anthropometric risk factors<br />

for patellar tendon injury among volleyball players. Br J<br />

Sports Med 2007;41:259�63.<br />

14. Skrzynski S. DSC study of collagen in disc disease. J Biophys<br />

2009;2009:819635, http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2009/819635.<br />

15. Luevano-Contreras C, Chapman-Novakofski K. Dietary<br />

advanced glycation end products and aging. Nutrients<br />

2010;2(12):1247�65 [2009;2009:819635].<br />

16. Abate M, Schiavone C, Pelotti P, Salini V. Limited joint<br />

mobility (LJM) in elderly subjects with type II diabetes<br />

mellitus. Arch Gerontol Geriatrics 2011;53:135�40.<br />

17. Sakellaridis N. The influence of diabetes mellitus on lumbar<br />

intervertebral disk herniation. Surg Neurol 2006;66:152�4.<br />

18. Shepherd PR, Kahn BB. Glucose transporters and insulin<br />

action: implications for insulin resistance and diabetes<br />

mellitus. New Eng J Med 1999;341(4):248�57.<br />

19. Abdul-Ghani MA, DeFronzo RA. Pathogenesis of insulin<br />

resistance in skeletal muscle. J Biomed Biotechnol 2010:19,<br />

http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2010/476279 [Article ID 476279].<br />

20. [Internet]American Heart Association. About metabolic<br />

syndrome. Dallas: The Association; 2014. [Available from<br />http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/More/<br />MetabolicSyndrome/About-Metabolic-Syndrome_UCM_<br />301920_Article.jsp].<br />

21. Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders.<br />

Nature 2006;444:860�7.<br />

22. Glass CK, Olefsky JM. Inflammation and lipid signaling in the<br />

etiology of insulin resistance. Cell Metab 2012;15(5):635�45.<br />

23. Reaven GM. All obese individuals are not created equal:<br />

insulin resistance is the major determinant of cardiovascular<br />

disease in overweight/obese individuals. Diabetes Vasc Dis<br />

Res 2005;2:105�12.<br />

24. Ritov VB, Menshikova EV, He J, Ferrell RE, Goodpaster<br />

BH, Kelley DE. Deficiency of subsarcolemmal mitochondria<br />

in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2005;54:8�14.<br />

25. Corcoran MP, Lamon-Fava S, Fielding RA. Trans fats and<br />

insulin resistance: skeletal muscle lipid deposition and insulin<br />

resistance: effect of dietary fatty acids and exercise. Am J Clin<br />

Nutr 2007;85:662�77.<br />

26. Schipper HS, Prakken B, Kalkhoven E, Boes M. Adipose<br />

tissue-resident immune cells: key players in immunometabolism.<br />

Trends Endocrinol Metab 2012;23:407�15.<br />

27. Antuna-Puente B, Feve B, Fellahi S, Bastard JP. Adipokines:<br />

the missing link between insulin resistance and obesity.<br />

Diabetes Metab 2008;34:2�11.<br />

28. Grimble RF. Inflammatory status and insulin resistance. Curr<br />

Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2003;5:551�9.<br />

29. Tilg H, Moschen AR. Inflammatory mechanisms in<br />

the regulation of insulin resistance. Mol Med 2008;3�4:222�31.<br />

30. Johnson DR, O’Conner JC, Satpathy A, Freund GG.<br />

Cytokines in type 2 diabetes. Vitam Horm 2006;74:405�41.<br />

31. Ridker PM, Wilson PW, Grundy SM. Should C-reactive<br />

protein be added to the metabolic syndrome and to<br />

assessment of global cardiovascular risk? Circulation 2004;<br />

109:2818�25.<br />

32. Gelaye B, Revilla L, Lopez T, et al. Association between<br />

insulin resistance and c-reactive protein among Peruvian<br />

adults. Diabetol Metab Syn 2010;2:30.<br />

33. Singh VP, Bali A, Singh N, et al. Advanced glycation end<br />

products and diabetic complications. Korean J Physiol<br />

Pharmacol 2014;18(1):1�14.<br />

34. Baker RG, Hayden MS. NF-kB, inflammation and metabolic<br />

disease. Cell Metab 2011;13(1):11�22.<br />

35. Purkayastha S, Cair D. Neuroinflammatory basis of metabolic<br />

syndrome. Mol Metab Nov 2013;2(4):356�63.<br />

36. Ehse JA, Boni-Schnetzler M, Faulenbach M, Donath MY.<br />

Macrophages, cytokines and beta-cell death in type 2 diabetes.<br />

Biochem Soc Trans 2008;36(3):340�2.<br />

37. Boni-Schnetzler M, Ehses JA, Faulenbach M, Donath MY.<br />

Insulitis in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2008;10<br />

(Suppl 4):201�4.<br />

38. Donath MY, Schumann DM, Faulenbach M, Ellingsgaard H,<br />

Perren A, Ehses JA. Islet inflammation in type 2<br />

diabetes: from metabolic stress to therapy. Diabetes Care<br />

2008;31(Suppl 2):S161�4.<br />

39. Donath MY, Boni-Schnetzler M, Ellingsgaard H, Ehses JA.<br />

Islet inflammation impairs the pancreatic beta-cell in type 2<br />

diabetes. Physiology 2009;24:325�31.<br />

40. Harford KA, Reynolds CM, McGillicuddy FC, Roche HM.<br />

Fats, inflammation and insulin resistance: insights to the role<br />

of macrophage and T-cell accumulation in adipose tissue.<br />

Proc Nutr Soc 2011;70:408�17.<br />

41. Munoz A, Costa M. Nutritionally mediated oxidative stress and<br />

inflammation. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2013;2013:610950, http://<br />

dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/610950.<br />

42. Wisse BE, Schwartz MW. Does hypothalamic inflammation<br />

cause obesity? Cell Metab 2009;10(4):241�2.<br />

43. Purkayastha S, Cair D. Neuroinflammatory basis of metabolic<br />

syndrome. Mol Metab Nov 2013;2(4):356�63.<br />

44. Calegari VC, Torsoni AS, Vanzela EC, Ara�jo EP, Morari<br />

J, Zoppi CC, et al. Inflammation of the hypothalamus leads<br />

to defective pancreatic islet function. J Biol Chem 2011;<br />

286(15):12870�80.<br />

45. Cordain L, Eaton SB, Sebastian A, et al. Origins and evolution<br />

of the Western diet: health implications for the 21st century.<br />

Am J Clin Nutr 2005;81:341�54.<br />

46. Barclay AW, Petocz P, McMillan-Price J, et al. Glycemic<br />

index, glycemic load, and chronic disease risk�a metaanalysis<br />

of observational studies. Am J Clin Nutr<br />

2008;87:627�37.<br />

47. Facchini FS, Hua N, Abbasi F, Reaven GM. Insulin resistance<br />

as a predictor of age-related disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab<br />

2001;86:3574�8.<br />

48. Lin H, Lee B, Ho Y, et al. Postprandial glucose improves the<br />

risk prediction of cardiovascular death beyond the metabolic<br />

syndrome in the nondiabetic population. Diabetes Care Sep<br />

2009;32(9):1721�6.<br />

49. O’Keefe JH, Bell DS. Postprandial hyperglycemia/<br />

hyperlipidemia (postprandial dysmetabolism) is a cardiovascular<br />

risk factor. Am J Cardiol 2007;100:899�904.<br />

50. Cao H. Adipocytokines in obesity and metabolic disease.<br />

J Endocrinol 2014;220(2):T47�59.<br />

51. Nah SS, Choi IY, Lee CK, et al. Effects of advanced glycation<br />

end products on the expression of COX2, PGE2 and NO in human osteoarthritic chondrocytes. Rheumatology (Oxford)<br />

2008;47(4):425�31.<br />

52. Abate M, Schiavone C, Pelotti P, Salini V. Limited joint<br />

mobility (LJM) in elderly subjects with type II diabetes<br />

mellitus. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2011;53:135�40.<br />

53. Robinson D, Mirovsky Y, Halperin N, Evron Z, Nevo Z.<br />

Changes in proteoglycans of intervertebral disc in diabetic<br />

patients: a possible cause of increased back pain. Spine<br />

1998;23:849�56.<br />

54. Sakellaridis N, Androulis A. Influence of diabetes mellitus on<br />

cervical intervertebral disc herniation. Clin Neurol Neurosurg<br />

2008;110:810�2.<br />

55. Jhawar BS, Fuchs CS, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ. Cardiovascular<br />

risk factors for physician-diagnosed lumbar disc<br />

herniation. Spine J 2006;6:684�91.<br />

56. Lotan R, Oron A, Anekstein Y, Shalmon E, Mirovsky Y.<br />

Lumbar stenosis and systemic diseases: is there any relevance.<br />

J Spinal Disord Tech 2008;21:247�51.<br />

57. Anekstein Y, Smorgick Y, Lotan R, et al. Diabetes mellitus as<br />

a risk factor for the development of lumbar spinal stenosis. Isr<br />

Med Assoc J 2010;12:16�20.<br />

58. Choi KM. Sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity. Endocrinol<br />

Metab (Seoul) 2013;28(2):86�9.<br />

59. D’hooge R, Cagnie B, Crombez G, et al. Increased<br />

intramuscular fatty infiltration without differences in lumbar<br />

muscle cross-sectional area during remission of unilateral<br />

recurrent low back pain. Man Ther 2012 Dec;17(6):5584�8.<br />

60. Chen YY, Pao JL, Liaw CK, et al. Image changes of paraspinal<br />

muscles and clinical correlations in patients with unilateral<br />

lumbar spinal stenosis. Eur Spine J 2014;23(5):999�1006.<br />

61. Kim Y, Park H. Does regular exercise without weight loss<br />

reduce insulin resistance in children and adolescents? In J<br />

Endocrinol 2013:402592, http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/<br />

402592 [Epub 2013 Dec 12].<br />

62. Strasser B, Siebert U, Schobersberger W. Resistance training<br />

in the treatment of the metabolic syndrome: a systematic<br />

review and meta-analysis of the effect of resistance training on<br />

metabolic clustering in patients with abnormal glucose<br />

metabolism. Sports Med 2010;40:397�415.<br />

63. Sharman MJ, Volek JS. Weight loss leads to reductions in<br />

inflammatory biomarkers after a very-low-carbohydrate diet<br />

and a low-fat diet in overweight men. Clin Sci (Lond)<br />

2004;13:365�9.<br />

64. Teng KT, Chang CY, Chang LF, et al. Modulation of obesityinduced<br />

inflammation by dietary fats: mechanisms and<br />

clinical evidence. Nutr J 2014;13:12, http://dx.doi.org/<br />

10.1186/1475-2891-13-12.<br />

65. Tzotzas T, Evangelou P, Kiortsis DN. Obesity, weight loss<br />

and conditional cardiovascular risk factors. Obes Rev 2011;12<br />

(5):e282�9.<br />

66. Stone N, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA<br />

Guideline on the Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce<br />

Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk in Adults: A report of<br />

the American College of Cardiology/American Heart<br />

Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation<br />

2014;129(25 Suppl 2):S1�S45.<br />

67. P�rez-Guisado J, Mu�oz-Serrano A. A pilot study of the<br />

Spanish ketogenic Mediterranean diet: an effective therapy for<br />

the metabolic syndrome. J Med Food 2011;14(7�8):681�7.<br />

68. P�rez-Guisado J, Mu�oz-Serrano A, Alonso-Moraga A.<br />

Spanish ketogenic Mediterranean diet: a healthy cardiovascular<br />

diet for weight loss. Nutr J 2008;7:30, http://dx.doi.org/<br />

10.1186/1475-2891-7-30.<br />

69. Jonsson T, Granfeldt Y, Lindeberg S, et al. Subjective satiety<br />

and other experiences of a Paleolithic diet compared to a<br />

diabetes diet in patients with T2DM. Nutr J 2013;12:105,<br />

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-12-105.<br />

70. Jonsson T, Granfeldt Y, Ahren B, et al. Beneficial effects of a<br />

Paleolithic diet on cardiovascular risk factors in T2DM: a<br />

randomized cross-over pilot study. Cardiovasc Diabetol<br />

2009;8:35, http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1475-2840-8-35.<br />

71. Nicklas BJ, You T, Pahor M. Behavioural treatments<br />

for chronic system inflammation: effects of dietary<br />

weight loss and exercise training. Can Med Assoc J<br />

2005;172(9):1199�209.<br />

72. O’Keefe JH, Gheewala NM, O’Keefe JO. Dietary<br />

strategies for improving post-prandial glucose, lipids, inflammation,<br />

and cardiovascular health. J Am Coll Cardiol<br />

2008;51:249�55.<br />

73. O’Keefe Jr JH, Cordain L. Cardiovascular disease resulting<br />

from a diet and lifestyle at odds with our Paleolithic genome:<br />

how to become a 21st-century hunter�gatherer. Mayo Clin<br />

Proc 2004;79(1):101�8.<br />

74. Ames BN. Low micronutrient intake may accelerate the<br />

degenerative diseases of aging through allocation of scarce<br />

micronutrients by triage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103<br />

(47):17589�94.<br />

75. Holick MF, Chen TC. Vitamin D deficiency: a worldwide<br />

problem with health consequences. Am J Clin Nutr<br />

2008;87:1080S�6S [Suppl.].<br />

76. Toubi E, Shoenfeld Y. The role of vitamin D in regulating<br />

immune responses. Isr Med Assoc J 2010;12(3):174�5.<br />

77. King DE, Mainous AG, Geesey ME, Egan BM, Rehman S.<br />

Magnesium supplement intake and C-reactive protein levels<br />

in adults. Nutr Res 2006;26:193�6.<br />

78. Rosanoff A, Weaver CM, Rude RK. Suboptimal magnesium<br />

status in the United States: are the health consequences<br />

underestimated? Nutr Rev 2012;70(3):153�64.<br />

79. Simopoulos AP. Omega-3 fatty acids in inflammation and<br />

autoimmune diseases. J Am Coll Nutr 2002;21(6):495�505.<br />

80. Simopoulos AP. The importance of the omega-6/omega-3<br />

fatty acid ratio in cardiovascular disease and other chronic<br />

diseases. Exp Biol Med 2008;233:674�88.<br />

81. Fung GJ, Steffen LM, Zhou X, et al. Vitamin D intake is<br />

inversely related to risk of developing metabolic syndrome<br />

in African American and white men and women over 20 y:<br />

the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults<br />

study. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;96(1):24�9 [Published online<br />2012 May 30].<br />

82. Palomer X, Gonzalez-Clemente JM, Blanco-Vaca F, Mauricio<br />

D. Role of vitamin D in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes<br />

mellitus. Diabetes Obes Metab 2008;10:185�97.<br />

83. Guadarrama-Lopez AL, Valdes-Ramos R, Martinex-Carrillo<br />

BE. T2DM, PUFAs, and vitamin D: their relation to<br />

inflammation. J Immunol Res 2014;2014:860703, http://dx.<br />

doi.org/10.1155/2014/860703.<br />

84. Cannell JJ, Hollis BW. Use of vitamin D in clinical practice.<br />

Altern Med Rev 2008;13(1):6�20.<br />

85. Davidson MB, Duran P, Lee ML, Friedman TC. High-dose<br />

vitamin D supplementation in people with prediabetes and<br />

hypovitaminosis D. Diabetes Care 2013;36(2):260�6, http://<br />

dx.doi.org/10.2337/dc12-1204.<br />

86. Schwalfenberg G. Vitamin D, and diabetes: improvement of<br />

glycemic control with vitamin D3 repletion. Can Fam<br />

Physician 2008;54:864�6.<br />

87. Kim DJ, Xun P, Liu K, et al. Magnesium intake in relation to<br />

systemic inflammation, insulin resistance, and the incidence<br />

of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2010;33(12):2604�10, http://dx.<br />

doi.org/10.2337/dc10-0994.<br />

88. Guerrero-Romero F, Tamez-Perez HE, Gonz�lez-Gonz�lez G,<br />

et al. Oral magnesium supplementation improves insulin<br />

sensitivity in non-diabetic subjects with insulin resistance. A<br />

double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trial. Diabetes<br />

Metab 2004;30(3):253�8.<br />

89. Rodr�guez-Mor�n M, Guerrero-Romero F. Oral magnesium<br />

supplementation improves insulin sensitivity and metabolic<br />

control in type 2 diabetic subjects: a randomized double-blind<br />

controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2003;26(4):1147�52.<br />

90. Song Y, He K, Levitan EB, Manson JE, Liu S. Effects of oral<br />

magnesium supplementation on glycaemic control in type 2<br />

diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized double-blind controlled<br />

trials. Diabet Med 2006;23(10):1050�6.<br />

91. Mooren FC, Kr�ger K, V�lker K, Golf SW,Wadepuhl M, Kraus<br />

A. Oral magnesium supplementation reduces insulin resistance<br />

in non-diabetic subjects�a double-blind, placebo-controlled,<br />

randomized trial. Diabetes Obes Metab 2011;13(3):281�4.<br />

92. Aggarwal BB. Targeting inflammation induced obesity and<br />

metabolic diseases by curcumin and other nutraceuticals.<br />

Annu Rev Nutr 2010;30:173�9.<br />

93. Alappat L, Awad AB. Curcumin and obesity: evidence and<br />

mechanisms. Nutr Rev 2010;68(12):729�38.<br />

94. Gonzales AM, Orlando RA. Curcumin and resveratrol inhibit<br />

nuclear factor-kappaB-mediated cytokine expression in adipocytes.<br />

Nutr Metab 2008;5:17, http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/<br />

1743-7075-5-17.<br />

95. Sahebkar A. Why it is necessary to translate curcumin into<br />

clinical practice for the prevention and treatment of metabolic<br />

syndrome? Biofactors 2012, http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/<br />

biof.1062 [Epub ahead of print].<br />

96. Hsu CH, Cheng AL. Clinical studies with curcumin. Adv Exp<br />

Med Biol 2007;595:471�80.<br />

97. Chuengsamarn S, Rattanamongkolgul S, Luechapudiporn R,<br />

Phisalaphong C, Jirawatnotai S. Curcumin extract for prevention<br />

of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012;35(11):2121�7.<br />

98. Jurenka JS. Anti-inflammatory properties of curcumin, a<br />

major constituent of curcuma longa: a review of preclinical<br />

and clinical research. Altern Med Rev 2009;14(2):141�53.<br />

99. Leach M. Gymnema sylvestre for diabetes mellitus: a systematic<br />

review. J Altern Complement Med 2007;13(9):977�83.<br />

100. Chattopadhyay R. A comparative evaluation of some blood<br />

sugar lowering agents of plant origin. J Ethnopharmacol<br />

1999;67:367�72.<br />

101. Nahas R, Moher M. Complementary and alternative medicine<br />

for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Can Fam Physician<br />

2009;55:591�6.<br />

102. Vanadium/Vanadyl sulfate: monograph. Altern Med Rev<br />

2009;14:17�80.<br />

103. Boden G, Chen X, Ruiz J, et al. Effects of vanadyl sulfate<br />

on carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in patients with noninsulin-dependent<br />

diabetes mellitus. Metabolism 1996;45:<br />

1130�5.<br />

104. Jacques-Camarena O, Gonz�lez-Ortiz M, Mart�nez-Abundis E,<br />

et al. Effect of vanadium on insulin sensitivity in patients with<br />

impaired glucose tolerance. Ann Nutr Metab 2008;53:195�8.<br />

105. Vincent JB. The biochemisty of chromium. J Nutr<br />

2000;130:715�8.<br />

106. Anderson RA. Chromium and insulin resistance. Nutr Res<br />

Rev 2003;16:267�75.<br />

107. Vincent JB. Chromium: celebrating 50 years as an essential<br />

element? Dalton Trans 2010;39:3787�94.<br />

108. Office of Dietary Supplements. [Internet]. Dietary supplement<br />

fact sheet: Chromium. Washington, DC: United States<br />

Department of Health and Human Services. http://ods.od.nih.<br />

gov/factsheets/chromium/. Reviewed November 4, 2013.<br />

109. Anderson RA. Chromium, glucose intolerance and diabetes.<br />

J Am Coll Nutr 1998;17(6):548�55.<br />

110. Cefalu WT, Rood J, Patricia Pinsonat P, et al. Characterization<br />

of the metabolic and physiologic response to chromium<br />

supplementation in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus.<br />

Metab Clin Exp 2010;59:755�62.<br />

111. Heimbach JT, Anderson RA. Chromium: recent studies regarding<br />

nutritional roles and safety. Nutr Today 2005;40(4):180�95.<br />

112. Shay KP, Moreau RF, Smith EJ, Smith AR, Hagen TM.<br />

Alpha-lipoic acid as a dietary supplement: molecular<br />

mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Biochim Biophys<br />

Acta 2009;1790:1149�60.<br />

113. Morikawa T, Yasuno R, Wada H. Do mammalian cells<br />

synthesize lipoic acid? Identification of a mouse cDNA<br />

encoding a lipoic acid synthase located in mitochondria.<br />

FEBS Lett 2001;498:16�21.<br />

114. Singh U, Jialal I. Alpha-lipoic acid supplementation and<br />

diabetes. Nutr Rev 2008;66(11):646�57.<br />

115. Padmalayam I, Hasham S, Saxena U, Pillarisetti S. Lipoic acid<br />

synthase (LASY): a novel role in inflammation, mitochondrial<br />

function, and insulin resistance. Diabetes 2009;58:600�8.<br />

116. Capasso I, Esposito E, Maurea N, et al. Combination of<br />

inositol and alpha lipoic acid in metabolic syndrome-affected<br />

women: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Trial<br />

2013;14:273, http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-14-273.<br />

117. Udupa A, Nahar P, Shah S, et al. A comparative study of<br />

effects of omega-3 fatty acids, alpha lipoic acid and vitamin E<br />

in T2DM. Ann Med Health Sci Res 2013;3(3):442�6.

There are 3 known types of negative reactions to wheat proteins, collectively known as wheat protein reactivity: wheat allergy (WA), gluten sensitivity (GS),�and celiac disease (CD). Of the 3, only CD is known to involve autoimmune reactivity, generation of antibodies, and intestinal mucosal damage. Wheat allergy involves the release of histamine by way of immunoglobulin (Ig) E cross-linking with gluten peptides and presents within hours after ingestion of wheat proteins. Gluten sensitivity is considered to be a diagnosis of exclusion; sufferers improve symptomatically with a gluten-free diet (GFD) but do not express antibodies or IgE reactivity.1

There are 3 known types of negative reactions to wheat proteins, collectively known as wheat protein reactivity: wheat allergy (WA), gluten sensitivity (GS),�and celiac disease (CD). Of the 3, only CD is known to involve autoimmune reactivity, generation of antibodies, and intestinal mucosal damage. Wheat allergy involves the release of histamine by way of immunoglobulin (Ig) E cross-linking with gluten peptides and presents within hours after ingestion of wheat proteins. Gluten sensitivity is considered to be a diagnosis of exclusion; sufferers improve symptomatically with a gluten-free diet (GFD) but do not express antibodies or IgE reactivity.1 A 28-year-old man presented to a chiropractic teaching clinic with complaints of constant muscle fasciculations of 2 years� duration. The muscle fasciculations originally started in the left eye and remained there for about 6 months. The patient then noticed that the fasciculations began to move to other areas of his body. They first moved into the right eye, followed by the lips,�and then to the calves, quadriceps, and gluteus muscles. The twitching would sometimes occur in a single muscle or may involve all of the above muscles simultaneously. Along with the twitches, he reports a constant �buzzing� or �crawling� feeling in his legs. There was no point during the day or night when the twitches ceased.

A 28-year-old man presented to a chiropractic teaching clinic with complaints of constant muscle fasciculations of 2 years� duration. The muscle fasciculations originally started in the left eye and remained there for about 6 months. The patient then noticed that the fasciculations began to move to other areas of his body. They first moved into the right eye, followed by the lips,�and then to the calves, quadriceps, and gluteus muscles. The twitching would sometimes occur in a single muscle or may involve all of the above muscles simultaneously. Along with the twitches, he reports a constant �buzzing� or �crawling� feeling in his legs. There was no point during the day or night when the twitches ceased. Discussion

Discussion The authors could not find any published case studies related to a presentation such as the one�described here. We believe this is a unique presentation of wheat protein reactivity and thereby represents a contribution to the body of knowledge in this field.

The authors could not find any published case studies related to a presentation such as the one�described here. We believe this is a unique presentation of wheat protein reactivity and thereby represents a contribution to the body of knowledge in this field. This report describes improvement in chronic, widespread muscle fasciculations and various other systemic symptoms with dietary change. There is strong suspicion that this case represents one of

This report describes improvement in chronic, widespread muscle fasciculations and various other systemic symptoms with dietary change. There is strong suspicion that this case represents one of

Nutrition is increasingly recognized as a key component of optimal sporting performance, with both the science and practice of sports nutrition developing rapidly.1 Recent studies have found that a planned scientific nutritional strategy (consisting of fluid, carbohydrate, sodium, and caffeine) compared with a self-chosen nutritional strategy helped non-elite runners complete a marathon run faster2 and trained cyclists complete a time trial faster.3 Whereas training has the greatest potential to increase performance, it has been estimated that consumption of a carbohydrate�electrolyte drink or relatively low doses of caffeine may improve a 40 km cycling time trial performance by 32�42 and 55�84 seconds, respectively.4

Nutrition is increasingly recognized as a key component of optimal sporting performance, with both the science and practice of sports nutrition developing rapidly.1 Recent studies have found that a planned scientific nutritional strategy (consisting of fluid, carbohydrate, sodium, and caffeine) compared with a self-chosen nutritional strategy helped non-elite runners complete a marathon run faster2 and trained cyclists complete a time trial faster.3 Whereas training has the greatest potential to increase performance, it has been estimated that consumption of a carbohydrate�electrolyte drink or relatively low doses of caffeine may improve a 40 km cycling time trial performance by 32�42 and 55�84 seconds, respectively.4

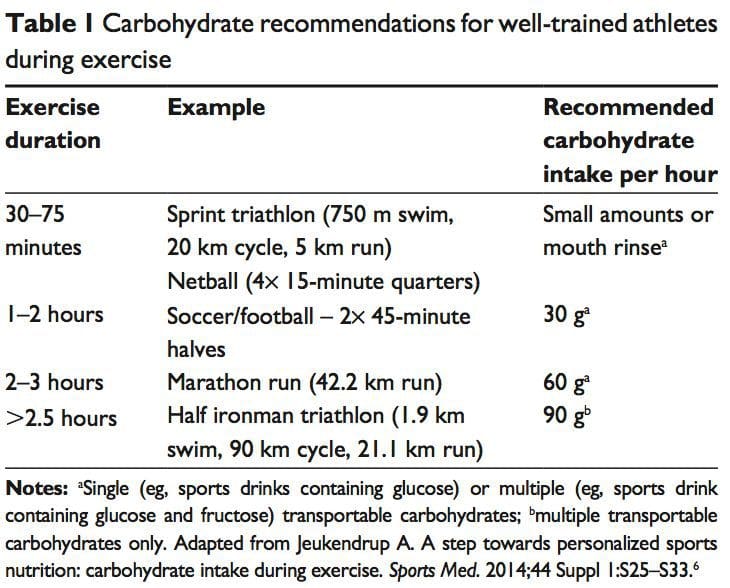

Carbohydrate ingestion has been shown to improve performance in events lasting approximately 1 hour.6 A growing body of evidence also demonstrates beneficial effects of a carbohydrate mouth rinse on performance.22 It is thought that receptors in the oral cavity signal to the central nervous system to positively modify motor output.23

Carbohydrate ingestion has been shown to improve performance in events lasting approximately 1 hour.6 A growing body of evidence also demonstrates beneficial effects of a carbohydrate mouth rinse on performance.22 It is thought that receptors in the oral cavity signal to the central nervous system to positively modify motor output.23

The �train-low, compete-high� concept is training with low carbohydrate availability to promote adaptations such as�enhanced activation of cell-signaling pathways, increased mitochondrial enzyme content and activity, enhanced lipid oxidation rates, and hence improved exercise capacity.26 However, there is no clear evidence that performance is improved with this approach.27 For example, when highly trained cyclists were separated into once-daily (train-high) or twice-daily (train-low) training sessions, increases in resting muscle glycogen content were seen in the low-carbohydrate- availability group, along with other selected training adaptations.28 However, performance in a 1-hour time trial after 3 weeks of training was no different between groups. Other research has produced similar results.29 Different strategies have been suggested (eg, training after an overnight fast, training twice per day, restricting carbohydrate during recovery),26 but further research is needed to establish optimal dietary periodization plans.27

The �train-low, compete-high� concept is training with low carbohydrate availability to promote adaptations such as�enhanced activation of cell-signaling pathways, increased mitochondrial enzyme content and activity, enhanced lipid oxidation rates, and hence improved exercise capacity.26 However, there is no clear evidence that performance is improved with this approach.27 For example, when highly trained cyclists were separated into once-daily (train-high) or twice-daily (train-low) training sessions, increases in resting muscle glycogen content were seen in the low-carbohydrate- availability group, along with other selected training adaptations.28 However, performance in a 1-hour time trial after 3 weeks of training was no different between groups. Other research has produced similar results.29 Different strategies have been suggested (eg, training after an overnight fast, training twice per day, restricting carbohydrate during recovery),26 but further research is needed to establish optimal dietary periodization plans.27 There has been a recent resurgence of interest in fat as a fuel, particularly for ultra endurance exercise. A high-carbohydrate strategy inhibits fat utilization during exercise,30 which may not be beneficial due to the abundance of energy stored in the body as fat. Creating an environment that optimizes fat oxidation potentially occurs when dietary carbohydrate is reduced to a level that promotes ketosis.31 However, this strategy may impair performance of high-intensity activity, by contributing to a reduction in pyruvate dehydrogenase activity and glycogenolysis. 32 The lack of performance benefits seen in studies investigating �high-fat� diets may be attributed to inadequate carbohydrate restriction and time for adaptation.31 Research into the performance effects of high fat diets continues.

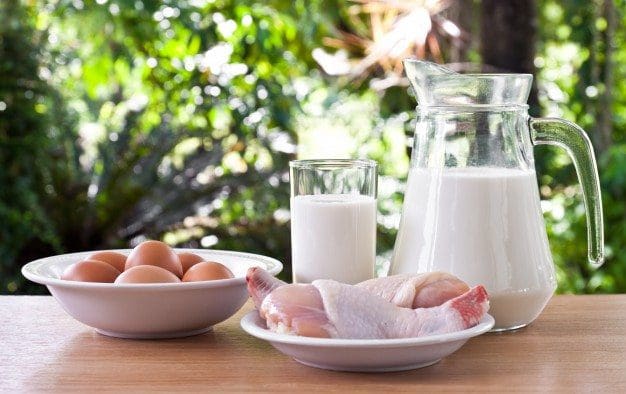

There has been a recent resurgence of interest in fat as a fuel, particularly for ultra endurance exercise. A high-carbohydrate strategy inhibits fat utilization during exercise,30 which may not be beneficial due to the abundance of energy stored in the body as fat. Creating an environment that optimizes fat oxidation potentially occurs when dietary carbohydrate is reduced to a level that promotes ketosis.31 However, this strategy may impair performance of high-intensity activity, by contributing to a reduction in pyruvate dehydrogenase activity and glycogenolysis. 32 The lack of performance benefits seen in studies investigating �high-fat� diets may be attributed to inadequate carbohydrate restriction and time for adaptation.31 Research into the performance effects of high fat diets continues. While protein consumption prior to and during endurance and resistance exercise has been shown to enhance rates of muscle protein synthesis (MPS), a recent review found protein ingestion alongside carbohydrate during exercise does not improve time�trial performance when compared with the ingestion of adequate amounts of carbohydrate alone.33

While protein consumption prior to and during endurance and resistance exercise has been shown to enhance rates of muscle protein synthesis (MPS), a recent review found protein ingestion alongside carbohydrate during exercise does not improve time�trial performance when compared with the ingestion of adequate amounts of carbohydrate alone.33 The purpose of fluid consumption during exercise is primarily to maintain hydration and thermoregulation, thereby benefiting performance. Evidence is emerging on increased risk of oxidative stress with dehydration.34 Fluid consumption prior to exercise is recommended to ensure that the athlete is well-hydrated prior to commencing exercise.35 In addition,�carefully planned hyperhydration ( fluid overloading) prior to an event may reset fluid balance and increase fluid retention, and consequently improve heat tolerance.36 However, fluid overloading may increase the risk of hyponatremia 37 and impact negatively on performance due to feelings of fullness and the need to urinate.

The purpose of fluid consumption during exercise is primarily to maintain hydration and thermoregulation, thereby benefiting performance. Evidence is emerging on increased risk of oxidative stress with dehydration.34 Fluid consumption prior to exercise is recommended to ensure that the athlete is well-hydrated prior to commencing exercise.35 In addition,�carefully planned hyperhydration ( fluid overloading) prior to an event may reset fluid balance and increase fluid retention, and consequently improve heat tolerance.36 However, fluid overloading may increase the risk of hyponatremia 37 and impact negatively on performance due to feelings of fullness and the need to urinate. Performance supplements shown to enhance performance include caffeine, beetroot juice, beta-alanine (BA), creatine, and bicarbonate.40 Comprehensive reviews on other supplements including caffeine, creatine, and bicarbonate can be found elsewhere.41 In recent years, research has focused on the role of nitrate, BA, and vitamin D and performance. Nitrate is most commonly provided as sodium nitrate or beetroot juice.42 Dietary nitrates are reduced (in mouth and stomach) to nitrites, and then to nitric oxide. During exercise, nitric oxide potentially influences skeletal muscle function through regulation of blood ow and glucose homeostasis, as well as mitochondrial respiration.43 During endurance exercise, nitrate supplementation has been shown to increase exercise efficiency (4%�5% reduction in VO at a steady attenuate oxidative stress.42 Similarly, a 4.2% improvement in performance was shown in a test designed to simulate a football game.44

Performance supplements shown to enhance performance include caffeine, beetroot juice, beta-alanine (BA), creatine, and bicarbonate.40 Comprehensive reviews on other supplements including caffeine, creatine, and bicarbonate can be found elsewhere.41 In recent years, research has focused on the role of nitrate, BA, and vitamin D and performance. Nitrate is most commonly provided as sodium nitrate or beetroot juice.42 Dietary nitrates are reduced (in mouth and stomach) to nitrites, and then to nitric oxide. During exercise, nitric oxide potentially influences skeletal muscle function through regulation of blood ow and glucose homeostasis, as well as mitochondrial respiration.43 During endurance exercise, nitrate supplementation has been shown to increase exercise efficiency (4%�5% reduction in VO at a steady attenuate oxidative stress.42 Similarly, a 4.2% improvement in performance was shown in a test designed to simulate a football game.44

Consuming carbohydrates immediately

Consuming carbohydrates immediately  An acute bout of intense endurance or resistance exercise can induce a transient increase in protein turnover, and, until feeding, protein balance remains negative. Protein consumption after exercise enhances MPS and net protein balance,58 predominantly by increasing mitochondrial protein fraction with endurance training, and myofibrillar protein fraction with resistance training.59

An acute bout of intense endurance or resistance exercise can induce a transient increase in protein turnover, and, until feeding, protein balance remains negative. Protein consumption after exercise enhances MPS and net protein balance,58 predominantly by increasing mitochondrial protein fraction with endurance training, and myofibrillar protein fraction with resistance training.59 Fluid and electrolyte replacement after exercise can be achieved through resuming normal hydration practices. However, when euhydration is needed within 24 hours or substantial body weight has been lost (.5% of BM), a more structured response may be warranted to replace fluids and electrolytes.77

Fluid and electrolyte replacement after exercise can be achieved through resuming normal hydration practices. However, when euhydration is needed within 24 hours or substantial body weight has been lost (.5% of BM), a more structured response may be warranted to replace fluids and electrolytes.77 The availability of nutrition information for athletes varies. Younger or recreational athletes are more likely to receive generalized nutritional information of poorer quality from individuals such as coaches.78 Elite athletes are more likely to have access to specialized sports-nutrition input from qualified professionals. A range of sports science and medicine support systems are in place in different countries to assist elite athletes,1 and nutrition is a key component of these services. Some countries have nutrition programs embedded within sports institutes (eg, Australia) or alternatively have National Olympic Committees that support nutrition programs (eg, United States of America).1 However, not all athletes at the elite level have access to sports-nutrition services. This may be due to financial constraints of the sport, geographical issues, and a lack of recognition of the value of a sports-nutrition service.78

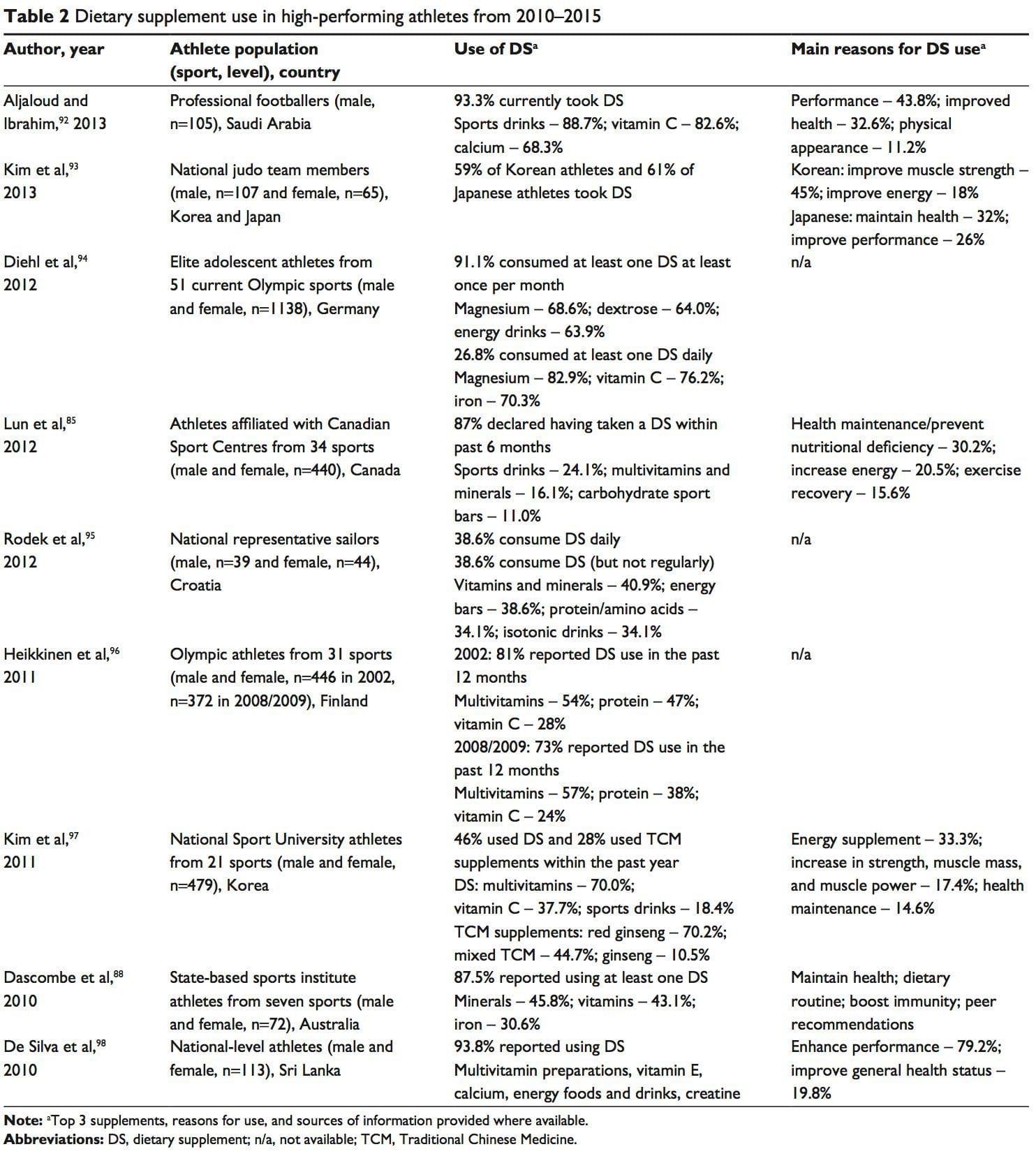

The availability of nutrition information for athletes varies. Younger or recreational athletes are more likely to receive generalized nutritional information of poorer quality from individuals such as coaches.78 Elite athletes are more likely to have access to specialized sports-nutrition input from qualified professionals. A range of sports science and medicine support systems are in place in different countries to assist elite athletes,1 and nutrition is a key component of these services. Some countries have nutrition programs embedded within sports institutes (eg, Australia) or alternatively have National Olympic Committees that support nutrition programs (eg, United States of America).1 However, not all athletes at the elite level have access to sports-nutrition services. This may be due to financial constraints of the sport, geographical issues, and a lack of recognition of the value of a sports-nutrition service.78 Supplement use is widespread in athletes.86,87 For example, 87.5% of elite athletes in Australia used dietary supplements88 and 87% of Canadian high-performance athletes took dietary supplements within the past 6 months85 (Table 2). It is difficult to compare studies due to differences in the criteria used to define dietary supplements, variations in assessing supplement intake, and disparities in the populations studied.85

Supplement use is widespread in athletes.86,87 For example, 87.5% of elite athletes in Australia used dietary supplements88 and 87% of Canadian high-performance athletes took dietary supplements within the past 6 months85 (Table 2). It is difficult to compare studies due to differences in the criteria used to define dietary supplements, variations in assessing supplement intake, and disparities in the populations studied.85 A positive drug test in an athlete can occur with even a minute quantity of a banned substance.41,87 WADA maintains a �strict liability� policy, whereby every athlete is responsible for any substance found in their body regardless of how it got there.41,86,87,89 The World Anti-Doping Code (January 1, 2015) does recognize the issue of contaminated supplements.91 Whereas the code upholds the principle of strict liability, athletes may receive a lesser ban if they can��show �no significant fault� to demonstrate they did not intend to cheat. The updated code imposes longer bans on those who cheat intentionally, includes athlete support personnel (eg, coaches, medical staff), and has an increased focus on anti-doping education.91,99