Evaluation of Patients Presenting with Knee Pain: Part II. Differential Diagnosis

The knee is the largest joint in the human body, where the complex structures of the lower and upper legs come together. Consisting of three bones, the femur, the tibia, and the patella which are surrounded by a variety of soft tissues, including cartilage, tendons and ligaments, the knee functions as a hinge, allowing you to walk, jump, squat or sit. As a result, however, the knee is considered to be one of the joints that are most prone to suffer injury. A knee injury is the prevalent cause of knee pain.

A knee injury can occur as a result of a direct impact from a slip-and-fall accident or automobile accident, overuse injury from sports injuries, or even due to underlying conditions, such as arthritis. Knee pain is a common symptom which affects people of all ages. It may also start suddenly or develop gradually over time, beginning as a mild or moderate discomfort then slowly worsening as time progresses. Moreover, being overweight can increase the risk of knee problems. The purpose of the following article is to discuss the evaluation of patients presenting with knee pain and demonstrate their differential diagnosis.

Abstract

Knee pain is a common presenting complaint with many possible causes. An awareness of certain patterns can help the family physician identify the underlying cause more efficiently. Teenage girls and young women are more likely to have patellar tracking problems such as patellar subluxation and patellofemoral pain syndrome, whereas teenage boys and young men are more likely to have knee extensor mechanism problems such as tibial apophysitis (Osgood-Schlatter lesion) and patellar tendonitis. Referred pain resulting from hip joint pathology, such as slipped capital femoral epiphysis, also may cause knee pain. Active patients are more likely to have acute ligamentous sprains and overuse injuries such as pes anserine bursitis and medial plica syndrome. Trauma may result in acute ligamentous rupture or fracture, leading to acute knee joint swelling and hemarthrosis. Septic arthritis may develop in patients of any age, but crystal-induced inflammatory arthropathy is more likely in adults. Osteoarthritis of the knee joint is common in older adults. (Am Fam Physician 2003;68:917-22. Copyright� 2003 American Academy of Family Physicians.)

Introduction

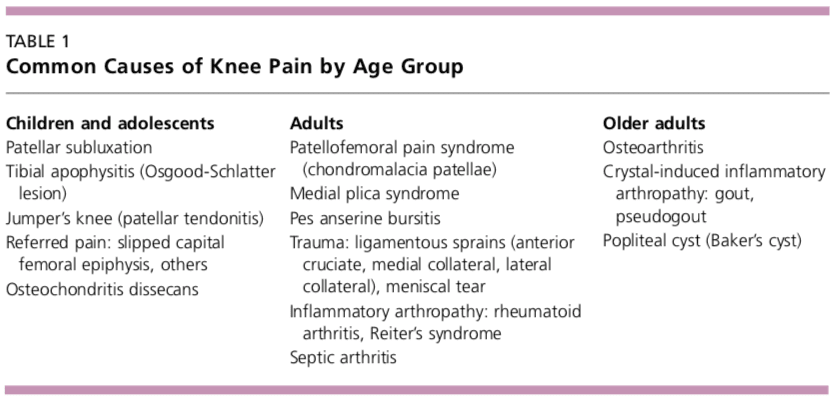

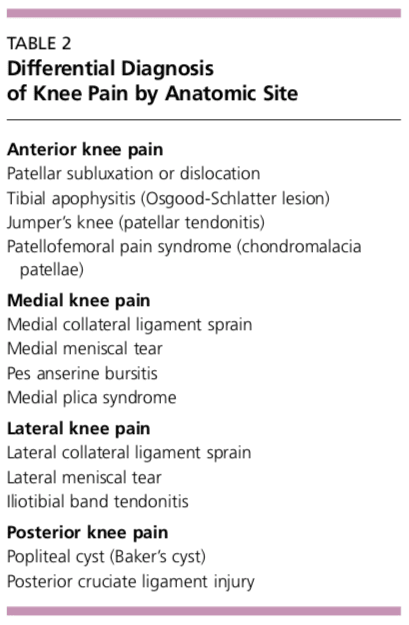

Determining the underlying cause of knee pain can be difficult, in part because of the extensive differential diagnosis. As discussed in part I of this two-part article,1 the family physician should be familiar with knee anatomy and common mechanisms of injury, and a detailed history and focused physical examination can narrow possible causes. The patient�s age and the anatomic site of the pain are two factors that can be important in achieving an accurate diagnosis (Tables 1 and 2). �

�

�

Children and Adolescents

Children and adolescents who present with knee pain are likely to have one of three common conditions: patellar subluxation, tibial apophysitis, or patellar tendonitis. Additional diagnoses to consider in children include slipped capital femoral epiphysis and septic arthritis.

Patellar Subluxation

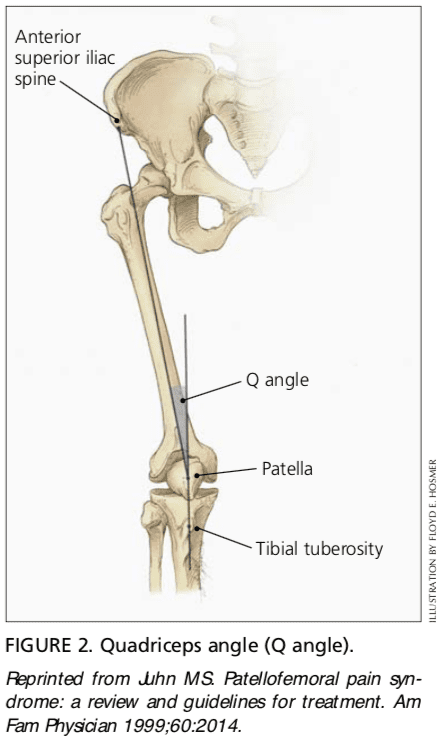

Patellar subluxation is the most likely diagnosis in a teenage girl who presents with giving-way episodes of the knee.2 This injury occurs more often in girls and young women because of an increased quadriceps angle (Q angle), usually greater than 15 degrees.

Patellar apprehension is elicited by subluxing the patella laterally, and a mild effusion is usually present. Moderate to severe knee swelling may indicate hemarthrosis, which suggests patellar dislocation with osteochondral fracture and bleeding.

Tibial Apophysitis

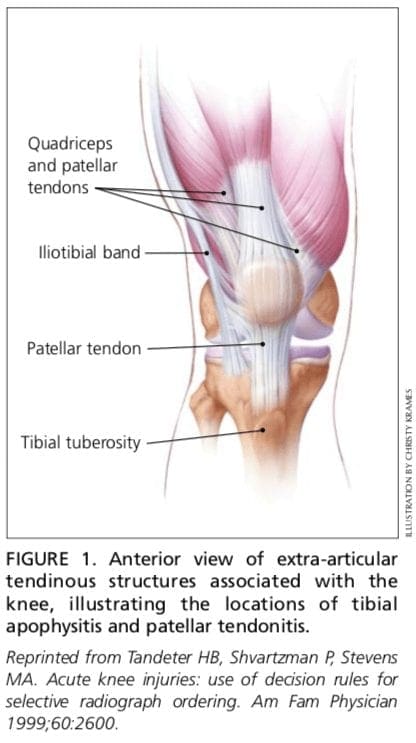

A teenage boy who presents with anterior knee pain localized to the tibial tuberosity is likely to have tibial apophysitis or Osgood- Schlatter lesion3,4 (Figure 1).5 The typical patient is a 13- or 14-year-old boy (or a 10- or 11-year-old girl) who has recently gone through a growth spurt.

The patient with tibial apophysitis generally reports waxing and waning of knee pain for a period of months. The pain worsens with�squatting, walking up or down stairs, or forceful contractions of the quadriceps muscle. This overuse apophysitis is exacerbated by jumping and hurdling because repetitive hard landings place excessive stress on the insertion of the patellar tendon.

On physical examination, the tibial tuberosity is tender and swollen and may feel warm. The knee pain is reproduced with the resisted active extension or passive hyperflexion of the knee. No effusion is present. Radiographs are usually negative; rarely, they show avulsion of the apophysis at the tibial tuberosity. However, the physician must not mistake the normal appearance of the tibial apophysis for an avulsion fracture. �

�

�

�

Patellar Tendonitis

Jumper�s knee (irritation and inflammation of the patellar tendon) most commonly occurs in teenage boys, particularly during a growth spurt2 (Figure 1).5 The patient reports vague anterior knee pain that has persisted for months and worsens after activities such as walking down stairs or running.

On physical examination, the patellar tendon is tender, and the pain is reproduced by resisted knee extension. There is usually no effusion. Radiographs are not indicated.

Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis

A number of pathologic conditions result in referral of pain to the knee. For example, the possibility of slipped capital femoral epiphysis must be considered in children and teenagers who present with knee pain.6 The patient with this condition usually reports poorly localized knee pain and no history of knee trauma.

The typical patient with slipped capital femoral epiphysis is overweight and sits on the examination table with the affected hip slightly flexed and externally rotated. The knee examination is normal, but hip pain is elicited with passive internal rotation or extension of the affected hip.

Radiographs typically show displacement of the epiphysis of the femoral head. However, negative radiographs do not rule out the diagnosis in patients with typical clinical findings. Computed tomographic (CT) scanning is indicated in these patients.

Osteochondritis Dissecans

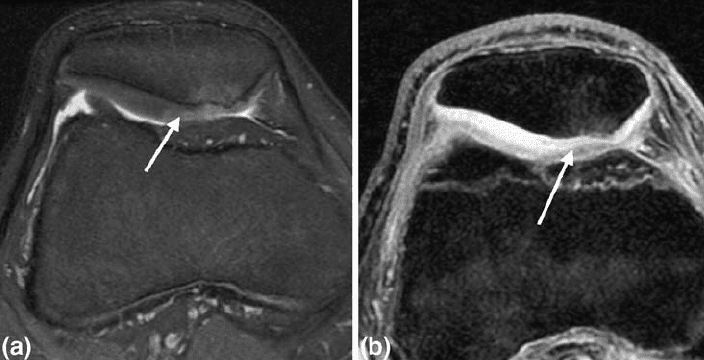

Osteochondritis dissecans is an intra-articular osteochondrosis of unknown etiology that is characterized by degeneration and recalcification of articular cartilage and underlying bone. In the knee, the medial femoral condyle is most commonly affected.7

The patient reports vague, poorly localized knee pain, as well as morning stiffness or recurrent effusion. If a loose body is present, mechanical symptoms of locking or catching of the knee joint also may be reported. On physical examination, the patient may demonstrate quadriceps atrophy or tenderness along the involved chondral surface. A mild joint effusion may be present.7

Plain-film radiographs may demonstrate the osteochondral lesion or a loose body in the knee joint. If osteochondritis dissecans is suspected, recommended radiographs include anteroposterior, posteroanterior tunnel, lateral, and Merchant�s views. Osteochondral lesions at the lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle may be visible only on the posteroanterior tunnel view. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is highly sensitive in detecting these abnormalities and is indicated in patients with a suspected osteochondral lesion.7 �

�

A knee injury caused by sports injuries, automobile accidents, or an underlying condition, among other causes, can affect the cartilage, tendons and ligaments which form the knee joint itself. The location of the knee pain can differ according to the structure involved, also, the symptoms can vary. The entire knee may become painful and swollen as a result of inflammation or infection, whereas a torn meniscus or fracture may cause symptoms in the affected region. Dr. Alex Jimenez D.C., C.C.S.T. Insight

Adults

Overuse Syndromes

Anterior Knee Pain. Patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome (chondromalacia patellae) typically present with a vague history of mild to moderate anterior knee pain that usually occurs after prolonged periods of sitting (the so-called �theater sign�).8 Patellofemoral pain syndrome is a common cause of anterior knee pain in women.

On physical examination, a slight effusion may be present, along with patellar crepitus on the range of motion. The patient�s pain may be reproduced by applying direct pressure to the anterior aspect of the patella. Patellar tenderness may be elicited by subluxing the patella medially or laterally and palpating the superior and inferior facets of the patella. Radiographs usually are not indicated.

Medial Knee Pain. One frequently overlooked diagnosis is medial plica syndrome. The plica, a redundancy of the joint synovium medially, can become inflamed with repetitive overuse.4,9 The patient presents with acute onset of medial knee pain after a marked increase in usual activities. On physical examination, a tender, mobile nodularity is present at the medial aspect of the knee, just anterior to the joint line. There is no joint effusion, and the remainder of the knee examination is normal. Radiographs are not indicated.

Pes anserine bursitis is another possible cause of medial knee pain. The tendinous insertion of the sartorius, gracilis, and semitendinosus muscles at the anteromedial aspect of the proximal tibia forms the pes anserine bursa.9 The bursa can become inflamed as a result of overuse or a direct contusion. Pes�anserine bursitis can be confused easily with a medial collateral ligament sprain or, less commonly, osteoarthritis of the medial compartment of the knee. �

�

�

The patient with pes anserine bursitis reports pain at the medial aspect of the knee. This pain may be worsened by repetitive flexion and extension. On physical examination, tenderness is present at the medial aspect of the knee, just posterior and distal to the medial joint line. No knee joint effusion is present, but there may be slight swelling at the insertion of the medial hamstring muscles. Valgus stress testing in the supine position or resisted knee flexion in the prone position may reproduce the pain. Radiographs are usually not indicated.

Lateral Knee Pain. Excessive friction between the iliotibial band and the lateral femoral condyle can lead to iliotibial band tendonitis.9 This overuse syndrome commonly occurs in runners and cyclists, although it may develop in any person subsequent to activity involving repetitive knee flexion. The tightness of the iliotibial band, excessive foot pronation, genu varum, and tibial torsion are predisposing factors.

The patient with iliotibial band tendonitis reports pain at the lateral aspect of the knee joint. The pain is aggravated by activity, particularly running downhill and climbing stairs. On physical examination, tenderness is present at the lateral epicondyle of the femur, approximately 3 cm proximal to the joint line. Soft tissue swelling and crepitus also may be present, but there is no joint effusion. Radiographs are not indicated.

Noble�s test is used to reproduce the pain in iliotibial band tendonitis. With the patient in a supine position, the physician places a thumb over the lateral femoral epicondyle as the�patient repeatedly flexes and extends the knee. Pain symptoms are usually most prominent with the knee at 30 degrees of flexion.

Popliteus tendonitis is another possible cause of lateral knee pain. However, this condition is fairly rare.10

Trauma

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Sprain. Injury to the anterior cruciate ligament usually occurs because of noncontact deceleration forces, as when a runner plants one foot and sharply turns in the opposite direction. Resultant valgus stress on the knee leads to anterior displacement of the tibia and sprain or rupture of the ligament.11 The patient usually reports hearing or feeling a �pop� at the time of the injury and must cease activity or competition immediately. Swelling of the knee within two hours after the injury indicates rupture of the ligament and consequent hemarthrosis.

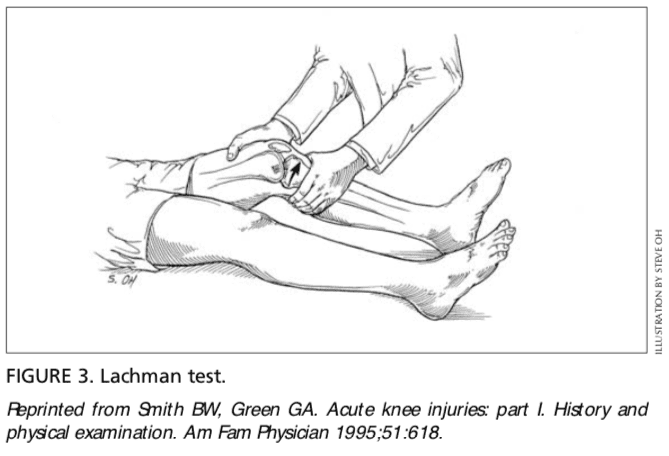

On physical examination, the patient has a moderate to severe joint effusion that limits the range of motion. The anterior drawer test may be positive, but can be negative because of hemarthrosis and guarding by the hamstring muscles. The Lachman test should be positive and is more reliable than the anterior drawer test (see text and Figure 3 in part I of the article1).

Radiographs are indicated to detect possible tibial spine avulsion fracture. MRI of the knee is indicated as part of a presurgical evaluation.

Medial Collateral Ligament Sprain. Injury to the medial collateral ligament is fairly common and is usually the result of acute trauma. The patient reports a misstep or collision that places valgus stress on the knee, followed by the immediate onset of pain and swelling at the medial aspect of the knee.11

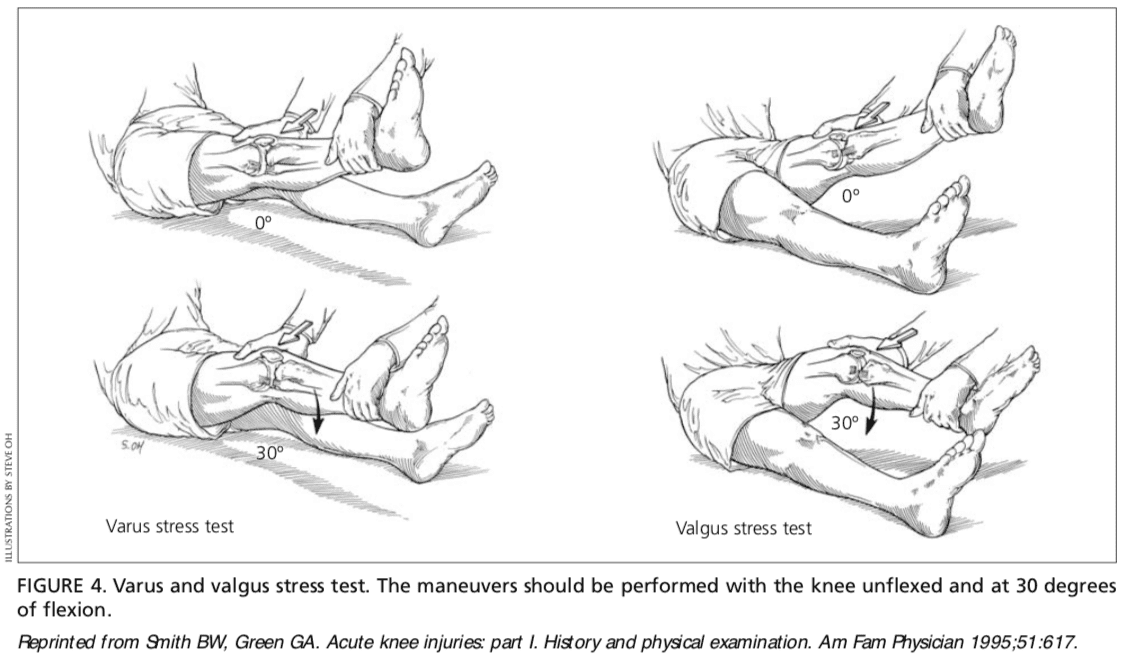

On physical examination, the patient with medial collateral ligament injury has point tenderness at the medial joint line. Valgus stress testing of the knee flexed to 30 degrees reproduces the pain (see text and Figure 4 in part I of this article1). A clearly defined endpoint on valgus stress testing indicates a grade 1�or grade 2 sprain, whereas complete medial instability indicates full rupture of the ligament (grade 3 sprain).

Lateral Collateral Ligament Sprain. Injury of the lateral collateral ligament is much less common than the injury of the medial collateral ligament. Lateral collateral ligament sprain usually results from varus stress to the knee, as occurs when a runner plants one foot and then turns toward the ipsilateral knee.2 The patient reports acute onset of lateral knee pain that requires prompt cessation of activity.

On physical examination, point tenderness is present at the lateral joint line. Instability or pain occurs with varus stress testing of the knee flexed to 30 degrees (see text and Figure 4 in part I of this article1). Radiographs are not usually indicated.

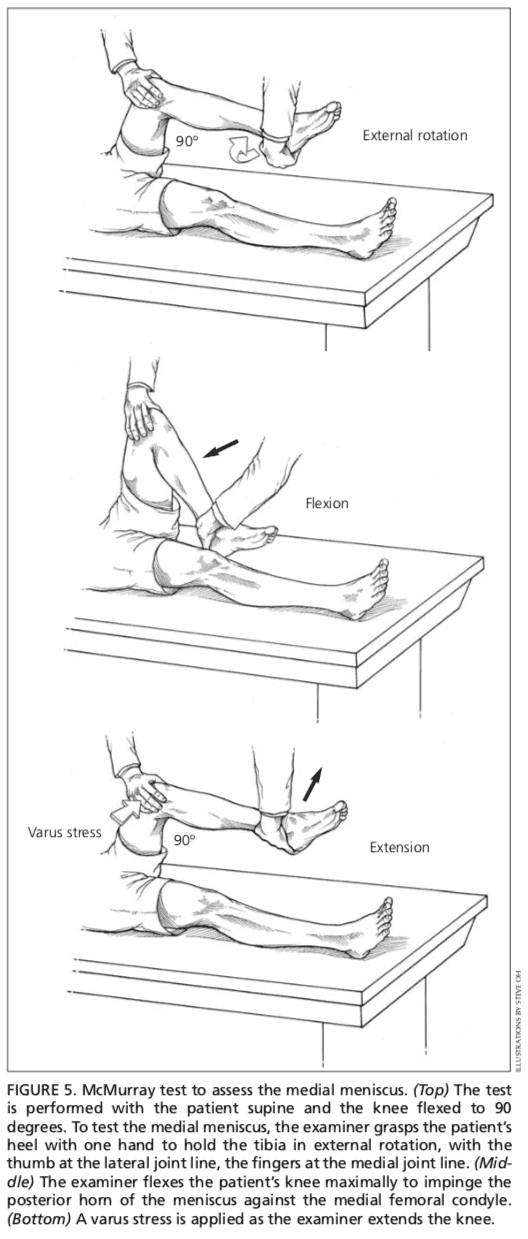

Meniscal Tear. The meniscus can be torn acutely with a sudden twisting injury of the knee, such as may occur when a runner suddenly changes direction.11,12 Meniscal tear also may occur in association with a prolonged degenerative process, particularly in a patient with an anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knee. The patient usually reports recurrent knee pain and episodes of catching or locking of the knee joint, especially with squatting or twisting of the knee.

On physical examination, a mild effusion is usually present, and there is tenderness at the medial or lateral joint line. Atrophy of the vastus medialis obliquus portion of the quadriceps muscle also may be noticeable. The McMurray test may be positive (see Figure 5 in part I of this article1), but a negative test does not eliminate the possibility of a meniscal tear.

Plain-film radiographs usually are negative and seldom are indicated. MRI is the radiologic test of choice because it demonstrates most significant meniscal tears.

Infection

Infection of the knee joint may occur in patients of any age but is more common in those whose immune system has been weakened by cancer, diabetes mellitus, alcoholism,�acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, or corticosteroid therapy. The patient with septic arthritis reports abrupt onset of pain and swelling of the knee with no antecedent trauma.13

On physical examination, the knee is warm, swollen, and exquisitely tender. Even slight motion of the knee joint causes intense pain.

Arthrocentesis reveals turbid synovial fluid. Analysis of the fluid yields a white blood cell count (WBC) higher than 50,000 per mm3 (50 ? 109 per L), with more than 75 percent (0.75) polymorphonuclear cells, an elevated protein content (greater than 3 g per dL [30 g per L]), and a low glucose concentration (more than 50 percent lower than the serum glucose concentration).14 Gram stain of the fluid may demonstrate the causative organism. Common pathogens include Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus species, Haemophilus influenza, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

Hematologic studies show an elevated WBC, an increased number of immature polymorphonuclear cells (i.e., a left shift), and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (usually greater than 50 mm per hour).

Older Adults

Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis of the knee joint is a common problem after 60 years of age. The patient presents with knee pain that is aggravated by weight-bearing activities and relieved by rest.15 The patient has no systemic symptoms but usually awakens with morning stiffness that dissipates somewhat with activity. In addition to chronic joint stiffness and pain, the patient may report episodes of acute synovitis.

Findings on physical examination include decreased range of motion, crepitus, a mild joint effusion, and palpable osteophytic changes at the knee joint.

When osteoarthritis is suspected, recommended radiographs include weight-bearing anteroposterior and posteroanterior tunnel views, as well as non-weight-bearing Merchants and lateral views. Radiographs show�joint-space narrowing, subchondral bony sclerosis, cystic changes, and hypertrophic osteophyte formation.

Crystal-Induced Inflammatory Arthropathy

Acute inflammation, pain, and swelling in the absence of trauma suggest the possibility of a crystal-induced inflammatory arthropathy such as gout or pseudogout.16,17 Gout commonly affects the knee. In this arthropathy, sodium urate crystals precipitate in the knee joint and cause an intense inflammatory response. In pseudogout, calcium pyrophosphate crystals are the causative agents.

On physical examination, the knee joint is erythematous, warm, tender, and swollen. Even minimal range of motion is exquisitely painful.

Arthrocentesis reveals clear or slightly cloudy synovial fluid. Analysis of the fluid yields a WBC count of 2,000 to 75,000 per mm3 (2 to 75 ? 109 per L), a high protein content (greater than 32 g per dL [320 g per L]), and a glucose concentration that is approximately 75 percent of the serum glucose con- centration.14 Polarized-light microscopy of the synovial fluid displays negatively birefringent rods in the patient with gout and positively birefringent rhomboids in the patient with pseudogout.

Popliteal Cyst

The popliteal cyst (Baker�s cyst) is the most common synovial cyst of the knee. It originates from the posteromedial aspect of the knee joint at the level of the gastrocnemio-semimembranous bursa. The patient reports insidious onset of mild to moderate pain in the popliteal area of the knee.

On physical examination, palpable fullness is present at the medial aspect of the popliteal area, at or near the origin of the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle. The McMurray test may be positive if the medial meniscus is injured. Definitive diagnosis of a popliteal cyst may be made with arthrography, ultrasonography, CT scanning, or, less commonly, MRI.

The authors indicate that they do not have any conflicts of interest. Sources of funding: none reported.

In conclusion, although the knee is the largest joint in the human body where the structures of the lower extremities meet, including the femur, the tibia, the patella, and many other soft tissues, the knee can easily suffer damage or injury and result in knee pain. Knee pain is one of the most common complaints among the general population, however, it commonly occurs in athletes. Sports injuries, slip-and-fall accidents, and automobile accidents, among other causes, can lead to knee pain.

As described in the article above, diagnosis is essential towards determining the best treatment approach for each type of knee injury, according to their underlying cause. While the location and the severity of the knee injury may vary depending on the cause of the health issue, knee pain is the most common symptom. Treatment options, such as chiropractic care and physical therapy, can help treat knee pain. The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic and spinal health issues. To discuss the subject matter, please feel free to ask Dr. Jimenez or contact us at�915-850-0900�.

Curated by Dr. Alex Jimenez �

�

�

Additional Topic Discussion: Relieving Knee Pain without Surgery

�

Knee pain is a well-known symptom which can occur due to a variety of knee injuries and/or conditions, including�sports injuries. The knee is one of the most complex joints in the human body as it is made-up of the intersection of four bones, four ligaments, various tendons, two menisci, and cartilage. According to the American Academy of Family Physicians, the most common causes of knee pain include patellar subluxation, patellar tendinitis or jumper’s knee, and Osgood-Schlatter disease. Although knee pain is most likely to occur in people over 60 years old, knee pain can also occur in children and adolescents. Knee pain can be treated at home following the RICE methods, however, severe knee injuries may require immediate medical attention, including chiropractic care.

�

�

�