Psychology, Headache, Back Pain, Chronic Pain and Chiropractic in El Paso, TX

Everyone experiences pain from time to time. Pain is a physical feeling of discomfort caused by injury or illness. When you pull a muscle or cut your finger, for instance, a signal is sent through the nerve roots to the brain, signaling you that something is wrong in the body. Pain may be different for everyone and there are several ways of feeling and describing pain. After an injury or illness heals, the pain will subside, however, what happens if the pain continues even after you’ve healed?

Chronic pain is often defined as any pain which lasts more than 12 weeks. Chronic pain can range from mild to severe and it can be the result of previous injury or surgery, migraine and headache, arthritis, nerve damage, infection and fibromyalgia. Chronic pain can affect an individual’s emotional and mental disposition, making it more difficult to relieve the symptoms. Research studies have demonstrated that psychological interventions can assist the chronic pain recovery process. Several healthcare professionals, like a doctor of chiropractic, can provide chiropractic care together with psychological interventions to help restore the overall health and wellness of their patients. The purpose of the following article is to demonstrate the role of psychological interventions in the management of patients with chronic pain, including headache and back pain.

The Role of Psychological Interventions in the Management of Patients with Chronic Pain

Abstract

Chronic pain can be best understood from a biopsychosocial perspective through which pain is viewed as a complex, multifaceted experience emerging from the dynamic interplay of a patient�s physiological state, thoughts, emotions, behaviors, and sociocultural influences. A biopsychosocial perspective focuses on viewing chronic pain as an illness rather than disease, thus recognizing that it is a subjective experience and that treatment approaches are aimed at the management, rather than the cure, of chronic pain. Current psychological approaches to the management of chronic pain include interventions that aim to achieve increased self-management, behavioral change, and cognitive change rather than directly eliminate the locus of pain. Benefits of including psychological treatments in multidisciplinary approaches to the management of chronic pain include, but are not limited to, increased self-management of pain, improved pain-coping resources, reduced pain-related disability, and reduced emotional distress � improvements that are effected via a variety of effective self-regulatory, behavioral, and cognitive techniques. Through implementation of these changes, psychologists can effectively help patients feel more in command of their pain control and enable them to live as normal a life as possible despite pain. Moreover, the skills learned through psychological interventions empower and enable patients to become active participants in the management of their illness and instill valuable skills that patients can employ throughout their lives.

Keywords: chronic pain management, psychology, multidisciplinary pain treatment, cognitive behavioral therapy for pain

Dr. Alex Jimenez’s Insight

Chronic pain has previously been determined to affect the psychological health of those with persistent symptoms, ultimately altering their overall mental and emotional disposition. In addition, patients with overlapping conditions, including stress, anxiety and depression, can make treatment a challenge. The role of chiropractic care is to restore as well as maintain and improve the original alignment of the spine through the use of spinal adjustments and manual manipulations. Chiropractic care allows the body to naturally heal itself without the need for drugs/medications and surgical interventions, although these can be referred to by a chiropractor if needed. However, chiropractic care focuses on the body as a whole, rather than on a single injury and/or condition and its symptoms. Spinal adjustments and manual manipulations, among other treatment methods and techniques commonly used by a chiropractor, require awareness of the patient’s mental and emotional disposition in order to effectively provide them with overall health and wellness. Patients who visit my clinic with emotional distress from their chronic pain are often more susceptible to experience psychological issues as a result. Therefore, chiropractic care can be a fundamental psychological intervention for chronic pain management, along with those demonstrated below.

Introduction

Pain is a ubiquitous human experience. It is estimated that approximately 20%�35% of adults experience chronic pain.[1,2] The National Institute of Nursing Research reports that pain affects more Americans than diabetes, heart disease, and cancer combined.[3] Pain has been cited as the primary reason to seek medical care in the United States.[4] Furthermore, pain relievers are the second most commonly prescribed medications in physicians� offices and emergency rooms.[5] Further solidifying the importance of adequate assessment of pain, the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations issued a mandate requiring that pain be evaluated as the fifth vital sign during medical visits.[6]

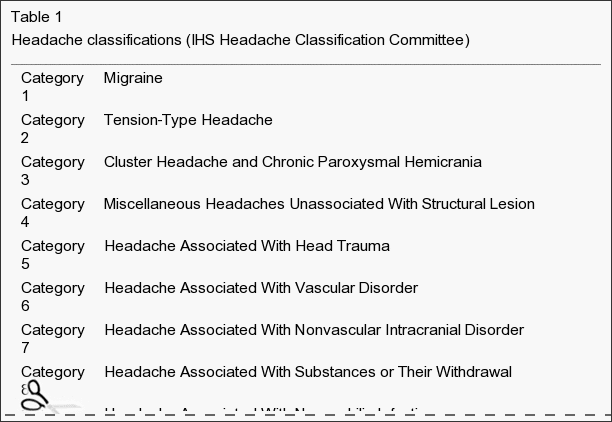

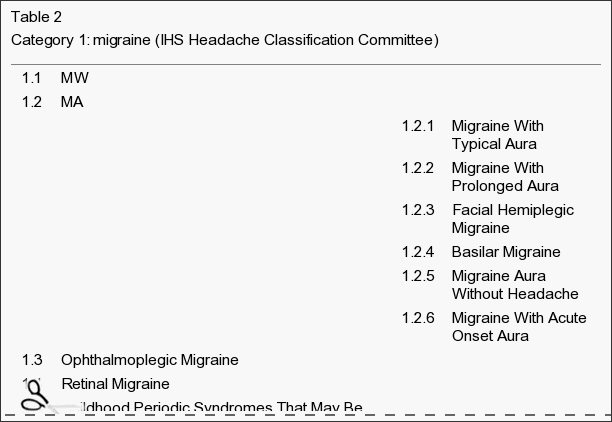

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines pain as �an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage�.[7] The IASP�s definition highlights the multidimensional and subjective nature of pain, a complex experience that is unique to each individual. Chronic pain is typically differentiated from acute pain based on its chronicity or persistence, its physiological maintenance mechanisms, and/or its detrimental impact on an individual�s life. Generally, it is accepted that pain that persists beyond the expected period of time for tissue healing following an injury or surgery is considered chronic pain. However, the specific timeframe constituting an expected healing period is variable and often difficult to ascertain. For ease of classification, certain guidelines suggest that pain persisting beyond a 3�6 month time window is considered chronic pain.[7] Nevertheless, classification of pain based solely on duration is a strictly practical and, in some instances, arbitrary criterion. More commonly, additional factors such as etiology, pain intensity, and impact are considered alongside duration when classifying chronic pain. An alternative way to characterize chronic pain has been based on its physiological maintenance mechanism; that is, pain that is thought to emerge as a result of peripheral and central reorganization. Common chronic pain conditions include musculoskeletal disorders, neuropathic pain conditions, headache pain, cancer pain, and visceral pain. More broadly, pain conditions may be primarily nociceptive (producing mechanical or chemical pain), neuropathic (resulting from nerve damage), or central (resulting from dysfunction in the neurons of the central nervous system).[8]

Unfortunately, the experience of pain is frequently characterized by undue physical, psychological, social, and financial suffering. Chronic pain has been recognized as the leading cause of long-term disability in the working- age American population.[9] Because chronic pain affects the individual at multiple domains of his/her existence it also constitutes an enormous financial burden to our society. The combined direct and indirect costs of pain have been estimated to range from $125 billion to $215 billion, annually.[10,11] The widespread implications of chronic pain include increased reports of emotional distress (eg, depression, anxiety, and frustration), increased rates of pain-related disability, pain-related alterations in cognition, and reduced quality of life. Thus, chronic pain can be best understood from a biopsychosocial perspective through which pain is viewed as a complex, multifaceted experience emerging from the dynamic interplay of a patient�s physiological state, thoughts, emotions, behaviors, and sociocultural influences.

Pain Management

Given the widespread prevalence of pain and its multi-dimensional nature, an ideal pain management regimen will be comprehensive, integrative, and interdisciplinary. Current approaches to the management of chronic pain have increasingly transcended the reductionist and strictly surgical, physical, or pharmacological approach to treatment. Current approaches recognize the value of a multidisciplinary treatment framework that targets not only nociceptive aspects of pain but also cognitive-evaluative, and motivational-affective aspects alongside equally unpleasant and impacting sequelae. The interdisciplinary management of chronic pain typically includes multimodal treatments such as combinations of analgesics, physical therapy, behavioral therapy, and psychological therapy. The multimodal approach more adequately and comprehensively addresses pain management at the molecular, behavioral, cognitive-affective, and functional levels. These approaches have been shown to lead to superior and long-lasting subjective and objective outcomes including pain reports, mood, restoration of daily functioning, work status, and medication or health care use; multimodal approaches have also been shown to be more cost-effective than unimodal approaches.[12,13] The focus of this review will be specifically on elucidating the benefits of psychology in the management of chronic pain.

Patients will typically initially present to a physician�s office in the pursuit of a cure or treatment for their ailment/acute pain. For many patients, depending on the etiology and pathology of their pain alongside biopsychosocial influences on the pain experience, acute pain will resolve with the passage of time, or following treatments aimed at targeting the presumed cause of pain or its transmission. Nonetheless, some patients will not achieve resolution of their pain despite numerous medical and complementary interventions and will transition from an acute pain state to a state of chronic, intractable pain. For instance, research has demonstrated that approximately 30% of patients presenting to their primary-care physician for complaints related to acute back pain will continue to experience pain and, for many others, severe activity limitations and suffering 12 months later.[14] As pain and its consequences continue to develop and manifest in diverse aspects of life, chronic pain may become primarily a biopsychosocial problem, whereby numerous biopsychosocial aspects may serve to perpetuate and maintain pain, thus continuing to negatively impact the affected individual�s life. It is at this point that the original treatment regimen may diversify to include other therapeutic components, including psychological approaches to pain management.

Psychological approaches for the management of chronic pain initially gained popularity in the late 1960s with the emergence of Melzack and Wall�s �gate-control theory of pain�[15] and the subsequent �neuromatrix theory of pain�.[16] Briefly, these theories posit that psychosocial and physiological processes interact to affect perception, transmission, and evaluation of pain, and recognize the influence of these processes as maintenance factors involved in the states of chronic or prolonged pain. Namely, these theories served as integral catalysts for instituting change in the dominant and unimodal approach to the treatment of pain, one heavily dominated by strictly biological perspectives. Clinicians and patients alike gained an increasing recognition and appreciation for the complexity of pain processing and maintenance; consequently, the acceptance of and preference for multidimensional conceptualizations of pain were established. Currently, the biopsychosocial model of pain is, perhaps, the most widely accepted heuristic approach to understanding pain.[17] A biopsychosocial perspective focuses on viewing chronic pain as an illness rather than disease, thus recognizing that it is a subjective experience and that treatment approaches are aimed at the management, rather than the cure, of chronic pain.[17] As the utility of a broader and more comprehensive approach to the management of chronic pain has become evident, psychologically-based interventions have witnessed a remarkable rise in popularity and recognition as adjunct treatments. The types of psychological interventions employed as part of a multidisciplinary pain treatment program vary according to therapist orientation, pain etiology, and patient characteristics. Likewise, research on the effectiveness of psychologically based interventions for chronic pain has shown variable, albeit promising, results on key variables studied. This overview will briefly describe frequently employed psychologically based treatment options and their respective effectiveness on key outcomes.

Current psychological approaches to the management of chronic pain include interventions that aim to achieve increased self-management, behavioral change, and cognitive change rather than directly eliminate the locus of pain. As such, they target the frequently overlooked behavioral, emotional, and cognitive components of chronic pain and factors contributing to its maintenance. Informed by the framework offered by Hoffman et al[18] and Kerns et al,[19] the following frequently employed psychologically-based treatment domains are reviewed: psychophysiological techniques, behavioral approaches to treatment, cognitive behavioral therapy, and acceptance-based interventions.

Psychophysiological Techniques

Biofeedback

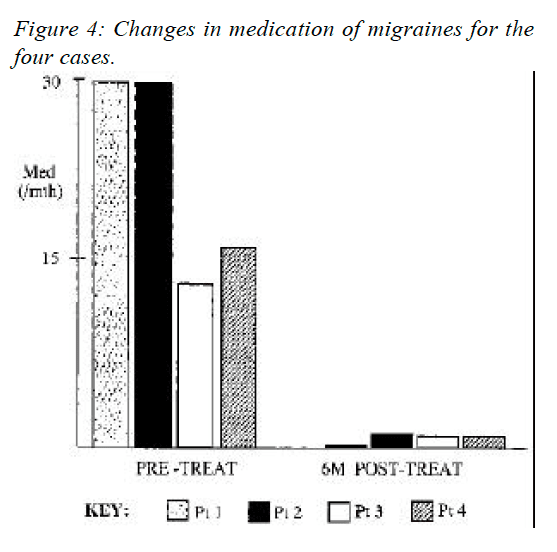

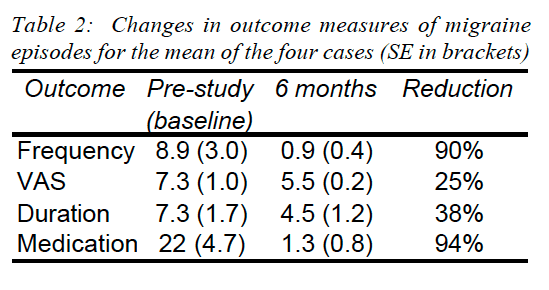

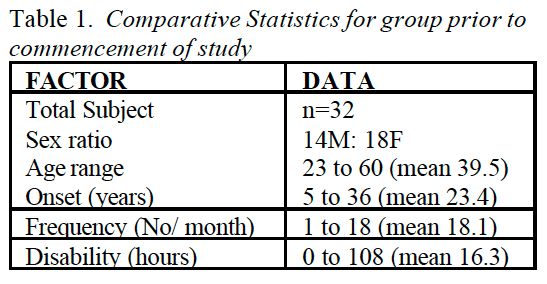

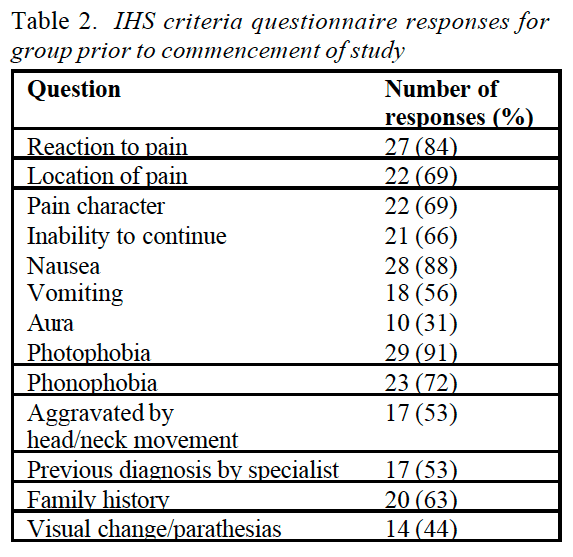

Biofeedback is a learning technique through which patients learn to interpret feedback (in the form of physiological data) regarding certain physiological functions. For instance, a patient may use biofeedback equipment to learn to recognize areas of tension in their body and subsequently learn to relax those areas to reduce muscular tension. Feedback is provided by a variety of measurement instruments that can yield information about brain electrical activity, blood pressure, blood flow, muscle tone, electrodermal activity, heart rate, and skin temperature, among other physiological functions in a rapid manner. The goal of biofeedback approaches is for the patient to learn how to initiate physiological self-regulatory processes by achieving voluntary control over certain physiological responses to ultimately increase physiological flexibility through greater awareness and specific training. Thus a patient will use specific self-regulatory skills in an attempt to reduce an undesired event (eg, pain) or maladaptive physiological reactions to an undesired event (eg, stress response). Many psychologists are trained in biofeedback techniques and provide these services as part of therapy. Biofeedback has been designated as an efficacious treatment for pain associated with headache and temporomandibular disorders (TMD).[20] A meta-analysis of 55 studies revealed that biofeedback interventions (including various biofeedback modalities) yielded significant improvements with regard to frequency of migraine attacks and perceptions of headache management self-efficacy when compared to control conditions.[21] Studies have provided empirical support for biofeedback for TMD, albeit more robust improvements with regard to pain and pain-related disability have been found for protocols that combine biofeedback with cognitive behavioral skills training, under the assumption that a combined treatment approach more comprehensively addresses the gamut of biopsychosocial problems that may be encountered as a result of TMD.[22]

Behavioral Approaches

Relaxation Training

It is generally accepted that stress is a key factor involved in the exacerbation and maintenance of chronic pain.[16,23] Stress can be predominantly of an environmental, physical, or psychological/emotional basis, though typically these mechanisms are intricately intertwined. The focus of relaxation training is to reduce tension levels (physical and mental) through activation of the parasympathetic nervous system and through attainment of greater awareness of physiological and psychological states, thereby achieving reductions in pain and increasing control over pain. Patients can be taught several relaxation techniques and practice them individually or in conjunction with one another, as well as adjuvant components to other behavioral and cognitive pain management techniques. The following are brief descriptions of relaxation techniques commonly taught by psychologists specializing in the management of chronic pain.

Diaphragmatic breathing. Diaphragmatic breathing is a basic relaxation technique whereby patients are instructed to use the muscles of their diaphragm as opposed to the muscles of their chest to engage in deep breathing exercises. Breathing by contracting the diaphragm allows the lungs to expand down (marked by expansion of abdomen during inhalation) and thus increase oxygen intake.[24]

Progressive muscle relaxation (PMR). PMR is characterized by engaging in a combination of muscle tension and relaxation exercises of specific muscles or muscle groups throughout the body.[25] The patient is typically instructed to engage in the tension/relaxation exercises in a sequential manner until all areas of the body have been addressed.

Autogenic training (AT). AT is a self-regulatory relaxation technique in which a patient repeats a phrase in conjunction with visualization to induce a state of relaxation.[26,27] This method combines passive concentration, visualization, and deep breathing techniques.

Visualization/Guided imagery. This technique encourages patients to use all of their senses in imagining a vivid, serene, and safe environment to achieve a sense of relaxation and distraction from their pain and pain-related thoughts and sensations.[27]

Collectively, relaxation techniques have generally been found to be beneficial in the management of a variety of types of acute and chronic pain conditions as well as in the management of important pain sequelae (eg, health-related quality of life).[28�31] Relaxation techniques are usually practiced in conjunction with other pain management modalities, and there is considerable overlap in the presumed mechanisms of relaxation and biofeedback, for instance.

Operant Behavior Therapy

Operant behavior therapy for chronic pain is guided by the original operant conditioning principles proposed by Skinner[32] and refined by Fordyce[33] to be applicable to pain management. The main tenets of the operant conditioning model as it relates to pain hold that pain behavior can eventually evolve into and be maintained as chronic pain manifestations as a result of positive or negative reinforcement of a given pain behavior as well as punishment of more adaptive, non-pain behavior. If reinforcement and the ensuing consequences occur with sufficient frequency, they can serve to condition the behavior, thus increasing the likelihood of repeating the behavior in the future. Therefore, conditioned behaviors occur as a product of learning of the consequences (actual or anticipated) of engaging in the given behavior. An example of a conditioned behavior is continued use of medication � a behavior that results from learning through repeated associations that taking medication is followed by removal of an aversive sensation (pain). Likewise, pain behaviors (eg, verbal expressions of pain, low activity levels) can be become conditioned behaviors that serve to perpetuate chronic pain and its sequelae. Treatments that are guided by operant behavior principles aim to extinguish maladaptive pain behaviors through the same learning principles that these may have been established by. In general, treatment components of operant behavior therapy include graded activation, time contingent medication schedules, and use of reinforcement principles to increase well behaviors and decrease maladaptive pain behaviors.

Graded activation. Psychologists can implement graded activity programs for chronic pain patients who have vastly reduced their activity levels (increasing likelihood of physical deconditioning) and subsequently experience high levels of pain upon engaging in activity. Patients are instructed to safely break the cycle of inactivity and deconditioning by engaging in activity in a controlled and time-limited fashion. In this manner, patients can gradually increase the length of time and intensity of activity to improve functioning. Psychologists can oversee progress and provide appropriate reinforcement for compliance, correction of misperceptions or misinterpretations of pain resulting from activity, where appropriate, and problem-solve barriers to adherence. This approach is frequently embedded within cognitive-behavioral pain management treatments.

Time-contingent medication schedules. A psychologist can be an important adjunct healthcare provider in overseeing the management of pain medications. In some cases, psychologists have the opportunity for more frequent and in-depth contact with patients than physicians and thus can serve as valuable collaborators of an integrated multidisciplinary treatment approach. Psychologists can institute time-contingent medication schedules to reduce the likelihood of dependence on pain medications for attaining adequate control over pain. Furthermore, psychologists are well equipped to engage patients in important conversations regarding the importance of proper adherence to medications and medical recommendations and problem-solve perceived barriers to safe adherence.

Fear-avoidance. The fear-avoidance model of chronic pain is a heuristic most frequently applied in the context of chronic low back pain (LBP).[34] This model draws largely from the operant behavior principles described previously. In essence, the fear-avoidance model posits that when acute pain states are repeatedly misinterpreted as danger signals or signs of serious injury, patients may be at risk of engaging in fear-driven avoidance behaviors and cognitions that further reinforce the belief that pain is a danger signal and perpetuate physical deconditioning. As the cycle continues, avoidance may generalize to broader types of activity and result in hypervigilance of physical sensations characterized by misinformed catastrophic interpretations of physical sensations. Research has shown that a high degree of pain catastrophizing is associated with maintenance of the cycle.[35] Treatments aimed at breaking the fear-avoidance cycle employ systematic graded exposure to feared activities to disconfirm the feared, often catastrophic, consequences of engaging in activities. Graded exposure is typically supplemented with psychoeducation about pain and cognitive restructuring elements that target maladaptive cognitions and expectations about activity and pain. Psychologists are in an excellent position to execute these types of interventions that closely mimic exposure treatments traditionally used in the treatment of some anxiety disorders.

Though specific graded exposure treatments have been shown to be effective in the treatment of complex regional pain syndrome type I (CRPS-1)[36] and LBP[37] in single-case designs, a larger-scale randomized controlled trial comparing systematic graded exposure treatment combined with multidisciplinary pain program treatment with multidisciplinary pain program treatment alone and with a wait-list control group found that the two active treatments resulted in significant improvements on outcome measures of pain intensity, fear of movement/injury, pain self-efficacy, depression, and activity level.[38] Results from this trial suggest that both interventions were associated with significant treatment effectiveness such that the graded exposure treatment did not appear to result in additional treatment gains.[38] A cautionary note in the interpretation of these results highlights that the randomized controlled trial (RCT) included a variety of chronic pain conditions that extended beyond LBP and CRPS-1 and did not exclusively include patients with high levels of pain-related fear; the interventions were also delivered in group formats rather than individual formats. Although in-vivo exposure treatments are superior at reducing pain catastrophizing and perceptions of harmfulness of activities, exposure treatments seem to be as effective as graded activity interventions in improving functional disability and chief complaints.[39] Another clinical trial compared the effectiveness of treatment-based classification (TBC) physical therapy alone to TBC augmented with graded activity or graded exposure for patients with acute and sub-acute LBP.[40] Outcomes revealed that there were no differences in 4-week and 6-month outcomes for reduction of disability, pain intensity, pain catastrophizing, and physical impairment among treatment groups, although graded exposure and TBC yielded larger reductions in fear-avoidance beliefs at 6 months.[40] Findings from this clinical trial suggest that enhancing TBC with graded activity or graded exposure does not lead to improved outcomes with regard to measures associated with the development of chronic LBP beyond improvements achieved with TBC alone.[40]

Cognitive-Behavioral Approaches

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) interventions for chronic pain utilize psychological principles to effect adaptive changes in the patient�s behaviors, cognitions or evaluations, and emotions. These interventions are generally comprised of basic psychoeducation about pain and the patient�s particular pain syndrome, several behavioral components, coping skills training, problem-solving approaches, and a cognitive restructuring component, though the exact treatment components vary according to the clinician. Behavioral components may include a variety of relaxation skills (as reviewed in the behavioral approaches section), activity pacing instructions/graded activation, behavioral activation strategies, and promotion of resumption of physical activity if there is a significant history of activity avoidance and subsequent deconditioning. The primary aim in coping skills training is to identify current maladaptive coping strategies (eg, catastrophizing, avoidance) that the patient is engaging in alongside their use of adaptive coping strategies (eg, use of positive self-statements, social support). As a cautionary note, the degree to which a strategy is adaptive or maladaptive and the perceived effectiveness of particular coping strategies varies from individual to individual.[41] Throughout treatment, problem-solving techniques are honed to aid patients in their adherence efforts and to help them increase their self-efficacy. Cognitive restructuring entails recognition of current maladaptive cognitions the patient is engaging in, challenging of the identified negative cognitions, and reformulation of thoughts to generate balanced, adaptive alternative thoughts. Through cognitive restructuring exercises, patients become increasingly adept at recognizing how their emotions, cognitions, and interpretations modulate their pain in positive and negative directions. As a result, it is presumed that the patients will attain a greater perception of control over their pain, be better able to manage their behavior and thoughts as they relate to pain, and be able to more adaptively evaluate the meaning they ascribe to their pain. Additional components sometimes included in a CBT intervention include social skills training, communication training, and broader approaches to stress management. Via a pain-oriented CBT intervention, many patients profit from improvements with regard to their emotional and functional well-being, and ultimately their global perceived health-related quality of life.

CBT interventions are delivered within a supportive and empathetic environment that strives to understand the patient�s pain from a biopsychosocial perspective and in an integrated manner. Therapists see their role as �teachers� or �coaches� and the message communicated to patients is that of learning to better manage their pain and improve their daily function and quality of life as opposed to aiming to cure or eradicate the pain. The overarching goal is to increase the patients� understanding of their pain and their efforts to manage pain and its sequelae in a safe and adaptive manner; therefore, teaching patients to self-monitor their behavior, thoughts, and emotions is an integral component of therapy and a useful strategy to enhance self-efficacy. Additionally, the therapist endeavors to foster an optimistic, realistic, and encouraging environment in which the patient can become increasingly skilled at recognizing and learning from their successes and learning from and improving upon unsuccessful attempts. In this manner, therapists and patients work together to identify patient successes, barriers to adherence, and to develop maintenance and relapse-prevention plans in a constructive, collaborative, and trustworthy atmosphere. An appealing feature of the cognitive behavioral approach is its endorsement of the patient as an active participant of his/her pain rehabilitation or management program.

Research has found CBT to be an effective treatment for chronic pain and its sequelae as marked by significant changes in various domains (ie, measures of pain experience, mood/affect, cognitive coping and appraisal, pain behavior and activity level, and social role function) when compared with wait-list control conditions.[42] When compared with other active treatments or control conditions, CBT has resulted in notable improvements, albeit smaller effects (effect size ~ 0.50), with regard to pain experience, cognitive coping and appraisal, and social role function.[42] A more recent meta-analysis of 52 published studies compared behavior therapy (BT) and CBT against treatment as usual control conditions and active control conditions at various time-points.[43] This meta-analysis concluded that their data did not lend support for BT beyond improvements in pain immediately following treatment when compared with treatment as usual control conditions.[43] With regard to CBT, they concluded that CBT has limited positive effects for pain disability, and mood; nonetheless, there are insufficient data available to investigate the specific influence of treatment content on selected outcomes.[43] Overall, it appears that CBT and BT are effective treatment approaches to improve mood; outcomes that remain robust at follow-up data points. However, as highlighted by several reviews and meta-analyses, a critical factor to consider in evaluating the effectiveness of CBT for the management of chronic pain is centered on issues of effective delivery, lack of uniform treatment components, differences in delivery across clinicians and treatment populations, and variability in outcome variables of interest across research trials.[13] Further complicating the interpretation of effectiveness findings are patient characteristics and additional variables that may independently affect treatment outcome.

Acceptance-Based Approaches

Acceptance-based approaches are frequently identified as third-wave cognitive-behavioral therapies. Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is the most common of the acceptance-based psychotherapies. ACT emphasizes the importance of facilitating the client�s progress toward attaining a more valued and fulfilling life by increasing psychological flexibility rather than strictly focusing on restructuring cognitions.[44] In the context of chronic pain, ACT targets ineffective control strategies and experiential avoidance by fostering techniques that establish psychological flexibility. The six core processes of ACT include: acceptance, cognitive defusion, being present, self as context, values, and committed action.[45] Briefly, acceptance encourages chronic pain patients to actively embrace pain and its sequelae rather than attempt to change it, in doing so encouraging the patient to cease a futile fight directed at the eradication of their pain. Cognitive defusion (deliteralization) techniques are employed to modify the function of thoughts rather than to reduce their frequency or restructure their content. In this manner, cognitive defusion may simply alter the undesirable meaning or function of negative thoughts and thus decrease the attachment and subsequent emotional and behavioral response to such thoughts. The core process of being present emphasizes a non-judgmental interaction between the self and private thoughts and events. Values are utilized as guides for electing behaviors and interpretations that are characterized by those values an individual strives to instantiate in everyday life. Finally, through committed action, patients can realize behavior changes aligned with individual values. Thus, ACT utilizes the six core principles in conjunction with one another to take a holistic approach toward increasing psychological flexibility and decreasing suffering. Patients are encouraged to view pain as inevitable and accept it in a nonjudgmental manner so that they can continue to derive meaning from life despite the presence of pain. The interrelated core processes exemplify mindfulness and acceptance processes and commitment and behavior change processes.[45]

Results of research on the effectiveness of ACT-based approaches for the management of chronic pain are promising, albeit still warranting further evaluation. A RCT comparing ACT with a waitlist control condition reported significant improvements in pain catastrophizing, pain-related disability, life satisfaction, fear of movements, and psychological distress that were maintained at the 7 month follow-up.[46] A larger trial reported significant improvements for pain, depression, pain-related anxiety, disability, medical visits, work status, and physical performance.[47] A recent meta-analysis evaluating acceptance-based interventions (ACT and mindfulness-based stress reduction) in patients with chronic pain found that, in general, acceptance-based therapies lead to favorable outcomes for patients with chronic pain.[48] Specifically, the meta-analysis revealed small to medium effect sizes for pain intensity, depression, anxiety, physical wellbeing, and quality of life, with smaller effects found when controlled clinical trials were excluded and only RCTs were included in the analyses.[48] Other acceptance-based interventions include contextual cognitive-behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, though empirical research on the effectiveness of these therapies for the management of chronic pain is still in its infancy.

Expectations

An important and vastly overlooked common underlying element of all treatment approaches is consideration of the patient�s expectation for treatment success. Despite the numerous advances in the formulation and delivery of effective multidisciplinary treatments for chronic pain, relatively little emphasis has been placed on recognizing the importance of expectations for success and on focusing efforts on enhancement of patients� expectations. The recognition that placebo for pain is characterized by active properties leading to reliable, observable, and quantifiable changes with neurobiological underpinnings is currently at the vanguard of pain research. Numerous studies have confirmed that, when induced in a manner that optimizes expectations (via manipulation of explicit expectations and/or conditioning), analgesic placebos can result in observable and measurable changes in pain perception at a conscious self-reported level as well as a neurological pain-processing level.[49,50] Analgesic placebos have been broadly defined as simulated treatments or procedures that occur within a psychosocial context and exert effects on an individual�s experience and/or physiology.[51] The current conceptualization of placebo emphasizes the importance of the psychosocial context within which placebos are embedded. Underlying the psychosocial context and ritual of treatment are patients� expectations. Therefore, it is not surprising that the placebo effect is intricately embedded in virtually every treatment; as such, clinicians and patients alike will likely benefit from recognition that therein lies an additional avenue by which current treatment approaches to pain can be enhanced.

It has been proposed that outcome expectancies are core influences driving the positive changes attained through the various modes of relaxation training, hypnosis, exposure treatments, and many cognitive-oriented therapeutic approaches. Thus, a sensible approach to the management of chronic pain capitalizes on the power of patients� expectations for success. Regrettably, too often, health care providers neglect to directly address and emphasize the importance of patients� expectations as integral factors contributing to successful management of chronic pain. The zeitgeist in our society is that of mounting medicalization of ailments fueling the general expectation that pain (even chronic pain) ought to be eradicated through medical advancements. These all too commonly held expectations leave many patients disillusioned with current treatment outcomes and contribute to an incessant search for the �cure�. Finding the �cure� is the exception rather than the rule with respect to chronic pain conditions. In our current climate, where chronic pain afflicts millions of Americans annually, it is in our best interest to instill and continue to advocate a conceptual shift that instead focuses on effective management of chronic pain. A viable and promising route to achieving this is to make the most of patients� positive (realistic) expectations and educate pain patients as well as the lay public (20% of whom will at some future point become pain patients) on what constitutes realistic expectations regarding the management of pain. Perhaps, this can occur initially through current, evidence-based education regarding placebo and nonspecific treatment effects such that patients can correct misinformed beliefs they may have previously held. Subsequently clinicians can aim to enhance patients� expectations within treatment contexts (in a realistic fashion) and minimize pessimistic expectations that deter from treatment success, therefore, learning to enhance their current multidisciplinary treatments through efforts guided at capitalizing on the improvements placebo can yield, even within an �active treatment�. Psychologists can readily address these issues with their patients and help them become advocates of their own treatment success.

Emotional Concomitants of Pain

An often challenging aspect of the management of chronic pain is the unequivocally high prevalence of comorbid emotional distress. Research has demonstrated that depression and anxiety disorders are upward to three times more prevalent among chronic pain patients than among the general population.[52,53] Frequently, pain patients with psychiatric comorbidities are labeled �difficult patients� by healthcare providers, possibly diminishing the quality of care they will receive. Patients with depression have poorer outcomes for both depression and pain treatments, compared with patients with single diagnoses of pain or depression.[54,55] Psychologists are remarkably suited to address most of the psychiatric comorbidities typically encountered in chronic pain populations and thus improve pain treatment outcomes and decrease the emotional suffering of patients. Psychologists can address key symptoms (eg, anhedonia, low motivation, problem-solving barriers) of depression that readily interfere with treatment participation and emotional distress. Moreover, irrespective of a psychiatric comorbidity, psychologists can help chronic pain patients process important role transitions they may undergo (eg, loss of job, disability), interpersonal difficulties they may be encountering (eg, sense of isolation brought about by pain), and emotional suffering (eg, anxiety, anger, sadness, disappointment) implicated in their experience. Thus, psychologists can positively impact the treatment course by reducing the influence of emotional concomitants that are addressed as part of therapy.

Conclusion

Benefits of including psychological treatments in multidisciplinary approaches to the management of chronic pain are abundant. These include, but are not limited to, increased self-management of pain, improved pain-coping resources, reduced pain-related disability, and reduced emotional distress-improvements that are effected via a variety of effective self-regulatory, behavioral, and cognitive techniques. Through implementation of these changes, a psychologist can effectively help patients feel more in command of their pain control and enable them to live as normal a life as possible despite pain. Moreover, the skills learned through psychological interventions empower and enable patients to become active participants in the management of their illness and instill valuable skills that patients can employ throughout their lives. Additional benefits of an integrated and holistic approach to the management of chronic pain may include increased rates of return to work, reductions in health care costs, and increased health-related quality of life for millions of patients throughout the world.

Footnotes

Disclosure: No conflicts of interest were declared in relation to this paper.

In conclusion, psychological interventions can be effectively used to help relieve symptoms of chronic pain along with the use of other treatment modalities, such as chiropractic care. Furthermore, the research study above demonstrated how specific psychological interventions can improve the outcome measures of chronic pain management. Information referenced from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic as well as to spinal injuries and conditions. To discuss the subject matter, please feel free to ask Dr. Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

Curated by Dr. Alex Jimenez

Additional Topics: Back Pain

According to statistics, approximately 80% of people will experience symptoms of back pain at least once throughout their lifetimes. Back pain is a common complaint which can result due to a variety of injuries and/or conditions. Often times, the natural degeneration of the spine with age can cause back pain. Herniated discs occur when the soft, gel-like center of an intervertebral disc pushes through a tear in its surrounding, outer ring of cartilage, compressing and irritating the nerve roots. Disc herniations most commonly occur along the lower back, or lumbar spine, but they may also occur along the cervical spine, or neck. The impingement of the nerves found in the low back due to injury and/or an aggravated condition can lead to symptoms of sciatica.

EXTRA IMPORTANT TOPIC: Managing Workplace Stress

MORE IMPORTANT TOPICS: EXTRA EXTRA: Car Accident Injury Treatment El Paso, TX Chiropractor