Stress Management & Low Back Pain in El Paso, TX

People experience stress on a regular basis. From worries about finances or employment to problems with your kids or significant other, even concerns about the condition of the world, can register as stressors for many individuals. Stress causes both acute (immediate) and chronic (long-term) health issues, including low back pain, a common symptom frequently reported by many patients who suffer from constant stress. Fortunately, several holistic treatment approaches, including chiropractic care, can help alleviate both the feelings and effect of stress, ultimately guiding people through proper stress management methods.

Symptoms of Stress

Stress triggers the body’s fight or flight response. The adrenaline surge you experience after hearing a loud sound is simply one of the remaining characteristics of our ancestors, afraid that that loud noise came from something which wanted to eat them.

Stress causes a number of physical changes in the body, starting with the brain. The heart rate increases and starts directing blood to the other extremities. Hearing and eyesight become more acute. And the adrenal glands begin secreting adrenaline as a means of preparing the body for physical exertion. This is exactly what the “flight or fight response” really means.

If you are walking alone at night and hear footsteps behind you, the fight of flight response can be incredibly effective towards your safety. However, if you experience prolonged stress, this sort of physical reaction contributes to a variety of health issues, such as high blood pressure, diabetes, a compromised immune system and muscle tissue damage. That’s because your body doesn’t recognize that there are different kinds of stress; it only knows that stress represents danger and it reacts accordingly.

Stress Management with Chiropractic Care

Chiropractic care can help improve as well as manage many symptoms of stress. This is because the spine is the root of the nervous system. Spinal adjustments and manual manipulations calm the fight or flight response by activating the parasympathetic system. Additionally, chiropractic can relieve pain and muscular tension, improve circulation, and correct spinal misalignments. These benefits all combine to ease the symptoms of stress, which reduces how stressed the patient feels.

A Well-Rounded Strategy

Chiropractors guide their patients through an assortment of stress management procedures, including dietary changes, exercise, meditation, and relaxation methods. A healthy diet can help the body handle an assortment of issues, including stress. Following a diet rich in fruits and vegetables, lean proteins, and complex carbohydrates, with minimal processed and prepackaged foods, can significantly improve overall health and wellness. Exercise is an effective stress reliever. The energy you expend through exercise relieves tension as well as the energy of stress. It also releases endorphins, which help elevate mood. Yoga is an especially effective kind of physical activity for relieving stress.

Meditation can be performed in a variety of ways and it can be practiced by various healthcare professionals. For some, writing in a journal is a kind of meditation, while others are more conventional in their strategy. Many relaxation techniques are closely linked to meditation, such as breathing exercises, releasing muscle tension, and listening to calming music or nature sounds.

- Breathing exercises are simple and offer immediate stress relief. Begin with inhaling slowly and deeply through your nose, while counting to six and extending your stomach. Hold your breath for a count of four, then release the breath through your mouth, counting to six again. Repeat the cycle for three to five occasions.

- Release muscle tension through a technique known as “progressive muscle relaxation”. Find a comfortable position, either sitting with your feet on the ground, or lying on your back. Work your way through each muscle group, beginning at your toes or your head, tensing the muscle for a count of five, and then releasing. Wait 30 minutes and then proceed to the next muscle group. Wondering how to tense the muscles of your face? For the face, raise your eyebrows as large as you can and feel the tension in your forehead and scalp. For the central portion of your own face, squint your eyes and wrinkle your nose and mouth. Finally, for the lower face, clench your teeth and pull back the corners of your mouth.

- Soothing sounds like instrumental music or nature sounds help relax the body and the brain.

Maintaining a balanced lifestyle while also incorporating chiropractic care as a stress management strategy is an effective way to help improve and cope with the symptoms of stress. Reducing stress can ultimately help maintain your overall well-being.

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction and Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Chronic Low Back Pain: Similar Effects on Mindfulness, Catastrophizing, Self-Efficacy and Acceptance in a Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is believed to improve chronic pain problems by decreasing patient catastrophizing and increasing patient self-efficacy for managing pain. Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) is believed to benefit chronic pain patients by increasing mindfulness and pain acceptance. However, little is known about how these therapeutic mechanism variables relate to each other or whether they are differentially impacted by MBSR versus CBT. In a randomized controlled trial comparing MBSR, CBT, and usual care (UC) for adults aged 20-70 years with chronic low back pain (CLBP) (N = 342), we examined (1) baseline relationships among measures of catastrophizing, self-efficacy, acceptance, and mindfulness; and (2) changes on these measures in the 3 treatment groups. At baseline, catastrophizing was associated negatively with self-efficacy, acceptance, and 3 aspects of mindfulness (non-reactivity, non-judging, and acting with awareness; all P-values <0.01). Acceptance was associated positively with self-efficacy (P < 0.01) and mindfulness (P-values < 0.05) measures. Catastrophizing decreased slightly more post-treatment with MBSR than with CBT or UC (omnibus P = 0.002). Both treatments were effective compared with UC in decreasing catastrophizing at 52 weeks (omnibus P = 0.001). In both the entire randomized sample and the sub-sample of participants who attended ?6 of the 8 MBSR or CBT sessions, differences between MBSR and CBT at up to 52 weeks were few, small in size, and of questionable clinical meaningfulness. The results indicate overlap across measures of catastrophizing, self-efficacy, acceptance, and mindfulness, and similar effects of MBSR and CBT on these measures among individuals with CLBP.

Keywords: chronic back pain, self-efficacy, mindfulness, acceptance, catastrophizing, CBT, MBSR

Introduction

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has been demonstrated effective, and is widely recommended, for chronic pain problems.[20] Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) also show promise for patients with chronic pain[12,14,25,44,65] and their use by this population is increasing. Understanding the mechanisms of action of psychosocial treatments for chronic pain and commonalities in these mechanisms across different therapies is critical to improving the effectiveness and efficiency of these treatments.[27,52] Key mechanisms of action of CBT for chronic pain include decreased catastrophizing and increased self-efficacy for managing pain.[6-8,56] Increased mindfulness is considered a central mechanism of change in MBIs,[14,26,30] which also increase pain acceptance.[16,21,27,38,59] However, little is known about the associations among pain catastrophizing, self-efficacy, acceptance, and mindfulness prior to psychosocial treatment or about differences in effects of CBT versus MBIs on these variables.

There is some evidence suggesting significant associations among these therapeutic mechanism variables. Evidence regarding relationships between catastrophizing and mindfulness is mixed. Some studies[10,18,46] have found negative associations between measures of pain catastrophizing and mindfulness. However, others found no significant relationship[19] or associations (inverse) between catastrophizing and some aspects of mindfulness (non-judging, non-reactivity, and acting with awareness) but not others (e.g., observing).[18] Catastrophizing has also been reported to be associated negatively with pain acceptance.[15,22,60] In a pain clinic sample, general acceptance of psychological experiences was associated negatively with catastrophizing and positively with mindfulness.[19] Pain self-efficacy has been observed to be correlated positively with acceptance and negatively with catastrophizing.[22]

Further suggesting overlap across mechanisms of different psychosocial treatments for chronic pain, increases in mindfulness[10] and acceptance[1,64] have been found after cognitive-behavioral pain treatments, and reductions in catastrophizing have been observed after mindfulness-based pain management programs.[17,24,37] Little research has examined effects of MBIs for chronic pain on self-efficacy, although a small pilot study of migraine patients found greater increases in self-efficacy with Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) training than with usual care.[63] We were unable to identify any studies of the relationships among all these therapeutic mechanism variables or of changes in all these variables with CBT versus an MBI for chronic pain.

The aim of this study was to replicate and extend prior research by using data from a randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing MBSR, CBT, and usual care (UC) for chronic low back pain (CLBP)[12] to examine: (1) baseline relationships among measures of mindfulness and pain catastrophizing, self-efficacy, and acceptance; and (2) short- and long-term changes on these measures in the 3 treatment groups. Based on theory and previous research, we hypothesized that: (1) at baseline, catastrophizing would be inversely related to acceptance, self-efficacy, and 3 dimensions of mindfulness (non-reactivity, non-judging, acting with awareness), but not associated with the observing dimension of mindfulness; (2) at baseline, acceptance would be associated positively with self-efficacy; and (3) from baseline to 26 and 52 weeks, acceptance and mindfulness would increase more with MBSR than with CBT and UC, and catastrophizing would decrease more and self-efficacy would increase more with CBT than with MBSR and UC.

Methods

Setting, Participants and Procedures

Study participants were enrolled in an RCT comparing group MBSR, group CBT, and UC for non-specific chronic back pain between September 2012 and April 2014. We previously reported details of the study methods,[13] Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram,[12] and outcomes.[12] In brief, participants were recruited from Group Health, an integrated healthcare system in Washington State, and from mailings to residents of communities served by Group Health. Eligibility criteria included age 20 – 70 years, back pain for at least 3 months, patient-rated bothersomeness of pain during the previous week ?4 (0 – 10 scale), and patient-rated pain interference with activities during the previous week ?3 (0 – 10 scale). We used International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM)43 diagnostic codes from electronic medical records (EMR) of visits in the previous year and telephone screening to exclude patients with specific causes of low back pain. Exclusion criteria also included pregnancy, spine surgery in the previous 2 years, disability compensation or litigation, fibromyalgia or cancer diagnosis, other major medical condition, plans to see a medical specialist for back pain, inability to read or speak English, and participation in a �mind-body� treatment for back pain in the past year. Potential participants were told that they would be randomized to one of �two different widely-used pain self-management programs that have been found helpful for reducing pain and making it easier to carry out daily activities� or to continued usual care. Those assigned to MBSR or CBT were unaware of the specific treatment they would receive until the first intervention session. The study was approved by the Group Health institutional review board and all participants provided informed consent.

Participants were randomized to the MBSR, CBT, or UC conditions. Randomization was stratified based on the baseline value of the primary outcome, a modified version of the Roland Disability Questionnaire (RDQ),[42] into 2 back pain-related physical limitation stratification groups: moderate (RDQ score ?12 on the 0 – 23 scale) and high (RDQ scores ?13). To mitigate possible disappointment with not being randomized to CBT or MBSR, participants randomized to UC received $50 compensation. Data were collected from participants in computer-assisted telephone interviews by trained survey staff. All participants were paid $20 for each interview completed.

Measures

Participants provided descriptive information at the screening and baseline interviews, and completed the study measures at baseline (before randomization) and 8 (post-treatment), 26 (the primary study endpoint), and 52 weeks post-randomization. Participants also completed a subset of the measures at 4 weeks, but these data were not examined for the current report.

Descriptive Measures and Covariates

The screening and baseline interviews assessed, among other variables not analyzed for the present study, sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, race, ethnicity, education, work status); pain duration (defined as length of time since a period of 1 or more weeks without low back pain); and number of days with back pain in the past 6 months. In this report, we describe the sample at baseline on these measures and on the primary outcome measures in the RCT: the modified Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RDQ)[42] and a numerical rating of back pain bothersomeness. The RDQ, a widely-used measure of back pain-related functional limitations, asks whether 24 specific activities are limited today by back pain (yes or no).[45] We used a modified version that included 23 items[42] and asked about the previous week rather than today only. Back pain bothersomeness was measured by participants� ratings of how bothersome their back pain was during the previous week on a 0 to 10 numerical rating scale (0 = �not at all bothersome� and 10 = �extremely bothersome�). The covariates for the current report were the same as those in our prior analyses of the interventions� effects on the outcomes:[12] age, gender, education, and pain duration (less than one year versus at least one year since experiencing 1 week without low back pain). We decided a priori to control for these variables because of their potential to affect the therapeutic mechanism measures, participant response to treatment, and/or likelihood of obtaining follow-up information.

Measures of Potential Therapeutic Mechanisms

Mindfulness. Mindfulness has been defined as the awareness that emerges through purposeful, non-judgmental attention to the present moment.[29] We administered 4 subscales of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire-Short Form (FFMQ-SF):[5] Observing (noticing internal and external experiences; 4 items); Acting with Awareness (attending to present moment activities, as contrasted to behaving automatically while attention is focused elsewhere; 5 items); Non-reactivity (non-reactivity to inner experiences: allowing thoughts and feelings to arise and pass away without attachment or aversion; 5 items); and Non-judging (non-judging of inner experiences: engaging in a non-evaluative stance towards thoughts, emotions, and feelings; 5-item scale; however, one question [�I make judgments about whether my thoughts are good or bad�] inadvertently was not asked.). The FFMQ-SF has been demonstrated to be reliable, valid, and sensitive to change.[5] Participants rated their opinion of what generally is true for them in terms of their tendency to be mindful in their daily lives (scale from 1 = �never or very rarely true� to 5 = �very often or always true�). For each scale, the score was calculated as the mean of the answered items and thus the possible range was 1-5, with higher scores indicating higher levels of the mindfulness dimension. Prior studies have used sum scores rather than means, but we elected to use mean scores given the greater ease of interpretation.

Pain catastrophizing. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) is a 13-item measure assessing pain-related catastrophizing, including rumination, magnification, and helplessness.[50] Participants rated the degree to which they had certain thoughts and feelings when experiencing pain (scale from 0 = �not at all� to 4 = �all the time�). Item responses were summed to yield a total score (possible range = 0-52). Higher scores indicate greater endorsement of catastrophic thinking in response to pain.

Pain acceptance. The Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire-8 (CPAQ-8), an 8-item version of the 20-item Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire (CPAQ), has been shown to be reliable and valid.[22,23] It has 2 scales: Activity Engagement (AE; engagement in life activities in a normal manner even while pain is being experienced) and Pain Willingness (PW; disengagement from attempts to control or avoid pain). Participants rated items on a scale from 0 (�never true�) to 6 (�always true�). Item responses were summed to create scores for each subscale (possible range 0-24) and the overall questionnaire (possible range 0-48). Higher scores indicate greater activity engagement/pain willingness/pain acceptance. Prior research suggests that the 2 subscales are moderately correlated and that each makes an independent contribution to the prediction of adjustment in people with chronic pain.[22]

Pain self-efficacy. The Pain Self-efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ) consists of 10 items assessing individuals� confidence in their ability to cope with their pain and engage in activities despite their pain, each rated on a scale from 0 = �not at all confident� to 6 = �completely confident.�[39] The questionnaire has been demonstrated to be valid, reliable, and sensitive to change.[39] Item scores are summed to yield a total score (possible range 0-60); higher scores indicate greater self-efficacy.

Interventions

The 2 interventions were comparable in format (group), duration, frequency, and number of participants per group cohort. Both the MBSR and CBT interventions consisted of 8 weekly 2-hour sessions supplemented by home activities. For each intervention, we developed a therapist/instructor’s manual and participant’s workbook, both with structured and detailed content for each session. In each intervention, participants were assigned home activities and there was emphasis on incorporating intervention content in their daily lives. Participants were given materials to read at home and CDs with relevant content for home practice (e.g., meditation, body scan, and yoga in MBSR; relaxation and imagery exercises in CBT). We previously published detailed descriptions of both interventions,[12,13] but describe them briefly here.

MBSR

The MBSR intervention was modeled closely after the original program developed by Kabat-Zinn[28] and based on the 2009 MBSR instructor’s manual.[4] It consisted of 8 weekly sessions and an optional 6-hour retreat between the 6th and 7th sessions. The protocol included experiential training in mindfulness meditation and mindful yoga. All sessions included mindfulness exercises (e.g., body scan, sitting meditation) and mindful movement (most commonly, yoga).

CBT

The group CBT protocol included the techniques most commonly applied in CBT for CLBP[20,58] and used in prior studies.[11,33,41,51,53-55,57,61] The intervention included: (1) education about (a) chronic pain, (b) maladaptive thoughts (including catastrophizing) and beliefs (e.g., inability to control pain, hurt equals harm) common among individuals with chronic pain, (c) the relationships between thoughts and emotional and physical reactions, (d) sleep hygiene, and (e) relapse prevention and maintenance of gains; and (2) instruction and practice in identifying and challenging unhelpful thoughts, generating alternative appraisals that are more accurate and helpful, setting and working towards behavioral goals, abdominal breathing and progressive muscle relaxation techniques, activity pacing, thought-stopping and distraction techniques, positive coping self-statements, and coping with pain flare-ups. None of these techniques were included in the MBSR intervention, and mindfulness, meditation, and yoga techniques were not included in CBT. CBT participants were also given a book (The Pain Survival Guide[53]) and asked to read specific chapters between sessions. During each session, participants completed a personal action plan for activities to do between sessions.

Usual Care

Patients assigned to UC received no MBSR training or CBT as part of the study and received whatever health care they would customarily receive during the study period.

Instructors/Therapists and Treatment Fidelity Monitoring

As previously reported,[12] all 8 MBSR instructors received formal training in teaching MBSR from the Center for Mindfulness at the University of Massachusetts or equivalent training and had extensive previous experience teaching MBSR. The CBT intervention was conducted by 4 Ph.D.-level licensed psychologists with previous experience providing individual and group CBT to patients with chronic pain. Details of instructor training and supervision and treatment fidelity monitoring were provided previously.[12]

Statistical Analyses

We used descriptive statistics to summarize the observed baseline characteristics by randomization group, separately for the entire randomized sample and the subsample of participants who attended 6 or more of the 8 intervention classes (MBSR and CBT groups only). To examine the associations between the therapeutic mechanism measures at baseline, we calculated Spearman rho correlations for each pair of measures.

To estimate changes over time in the therapeutic mechanism variables, we constructed linear regression models with the change from baseline as the dependent variable, and included all post-treatment time points (8, 26, and 52 weeks) in the same model. A separate model was estimated for each therapeutic mechanism measure. Consistent with our approach for analyzing outcomes in the RCT,[12] we adjusted for age, gender, education, and baseline values of pain duration, pain bothersomeness, the modified RDQ, and the therapeutic mechanism measure of interest in that model. To estimate the treatment effect (difference between groups in change on the therapeutic mechanism measure) at each time point, the models included main effects for treatment group (CBT, MBSR, and UC) and time point (8, 26, and 52 weeks), and terms for the interactions between these variables. We used generalized estimating equations (GEE)[67] to fit the regression models, accounting for possible correlation between repeated measures from individual participants. To account for potential bias caused by differential attrition across treatment groups, our primary analysis used a 2-step GEE modeling approach to impute missing data on the therapeutic mechanism measures. This approach uses a pattern mixture model framework for non-ignorable non-response and adjusts the variance estimates in the final outcome model parameters to account for using imputed data.[62] We also, as a sensitivity analysis, conducted the regression analyses again with observed rather than imputed data to evaluate whether using imputed data had a substantial effect on the results and to allow direct comparison to other published studies.

The primary analysis included all randomized participants, using an intent-to-treat (ITT) approach. We repeated the regression analyses using the subsample of participants who were randomized to MBSR or CBT and who attended at least 6 of the 8 sessions of their assigned treatment (�as-treated� or �per protocol� analysis). For descriptive purposes, using regression models for the ITT sample with imputed data, we estimated mean scores (and their 95% confidence intervals [CI]) on the therapeutic mechanism variables at each time point adjusted for age, gender, education, and baseline values of pain duration, pain bothersomeness, and the modified RDQ.

To provide context for interpreting the results, we used t-tests and chi-square tests to compare the baseline characteristics of participants who did versus did not complete at least 6 of the 8 intervention sessions (MBSR and CBT groups combined). We compared intervention participation by group, using a chi-square test to compare the proportions of participants randomized to MBSR versus CBT who completed at least 6 of the 8 sessions.

Dr. Alex Jimenez’s Insight

Stress is primarily a part of the “fight or flight” response which helps the body effectively prepare for danger. When the body enters�a state of mental or emotional strain or tension due to adverse or very demanding circumstances,�a complex mix of hormones and chemicals, such as adrenaline, cortisol and norepinephrine, are secreted in order to prepare the body for physical and psychological action.�While short-term stress provides us with the necessary amount of edge required to improve our overall performance, long-term stress has been associated to a variety of health issues, including low back pain and sciatica. Stress management methods and techniques, including meditation and chiropractic care, have been demonstrated to help improve treatment outcomes of low back pain and sciatica. The following article discusses several types of stress management treatments and describes their effect on overall health and wellness.

Results

Characteristics of the Study Sample

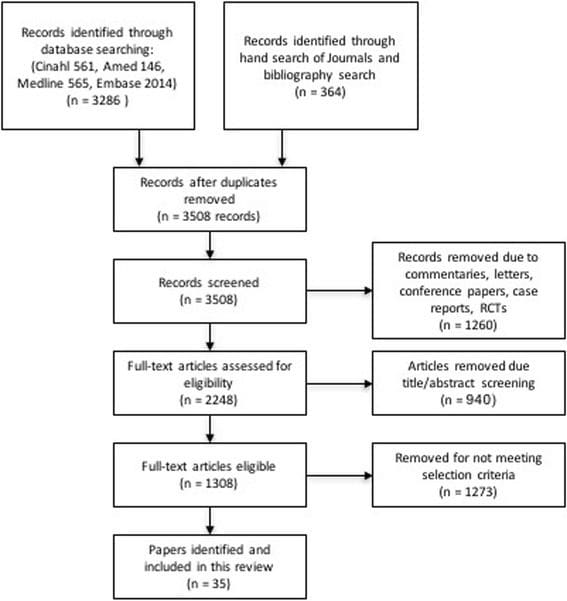

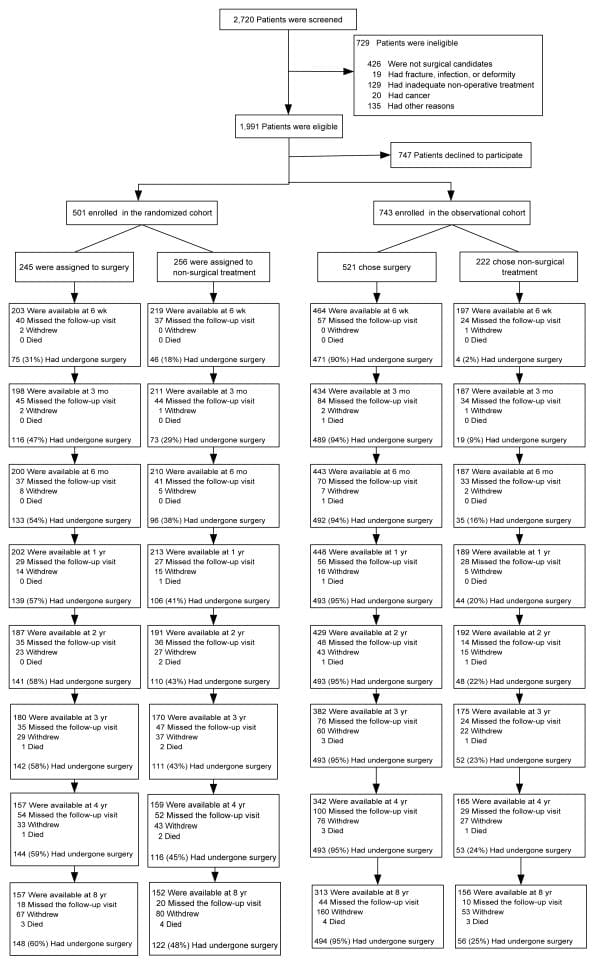

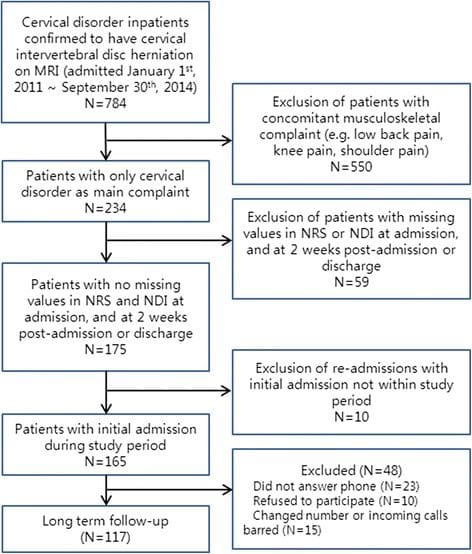

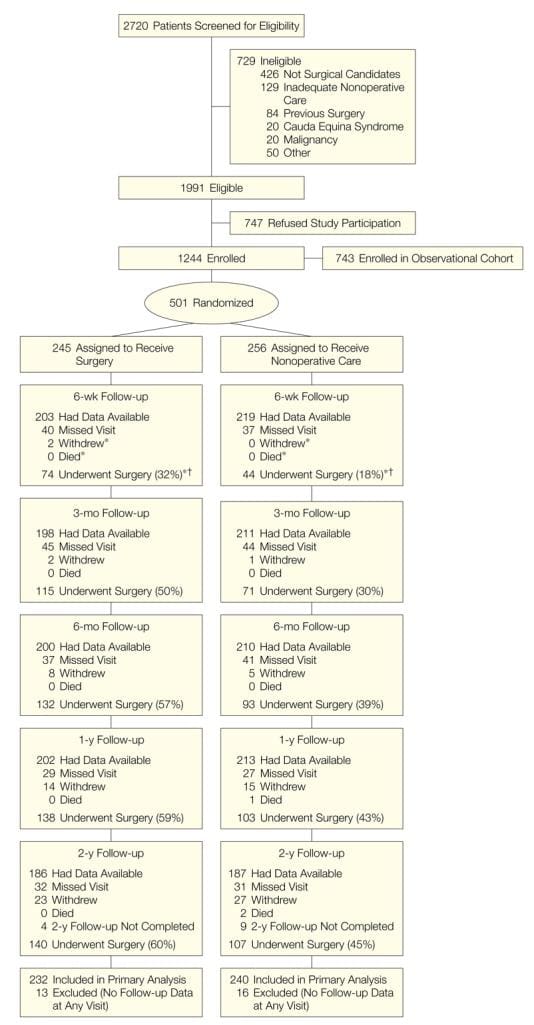

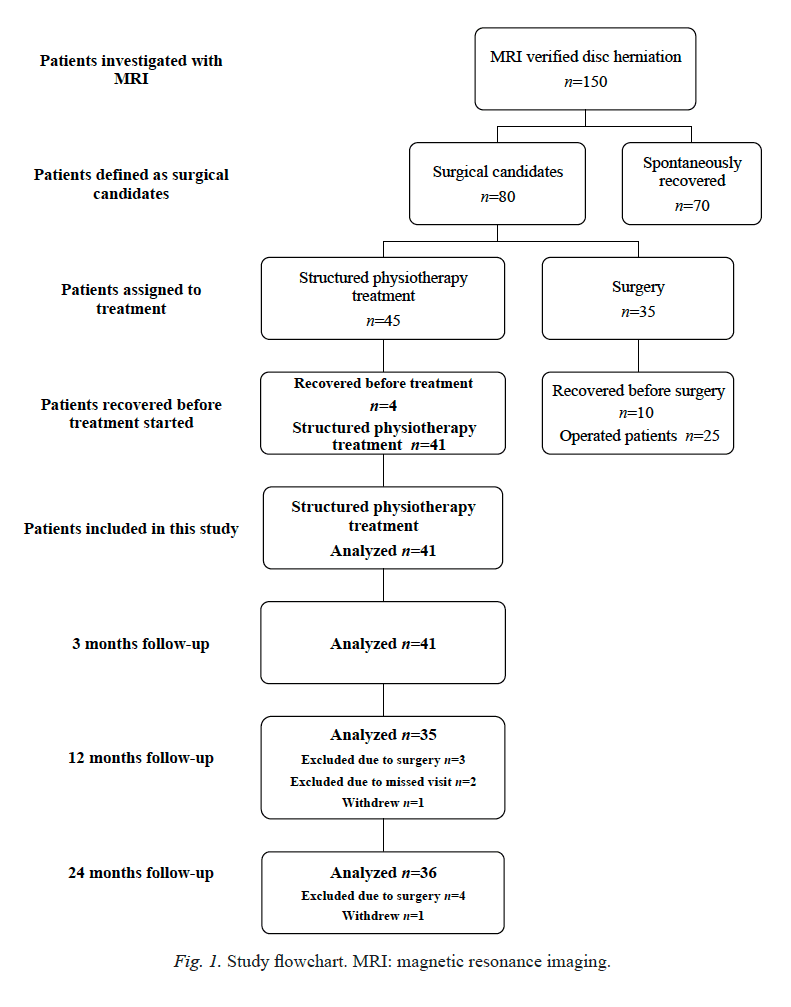

As previously reported,[12] among 1,767 individuals who expressed interest in the study and were screened for eligibility, 1,425 were excluded (most commonly due to pain not present for more than 3 months and inability to attend the intervention sessions). The remaining 342 individuals enrolled and were randomized. Among the 342 individuals randomized, 298 (87.1%), 294 (86.0%), and 290 (84.8%) completed the 8-, 26-, and 52-week assessments, respectively.

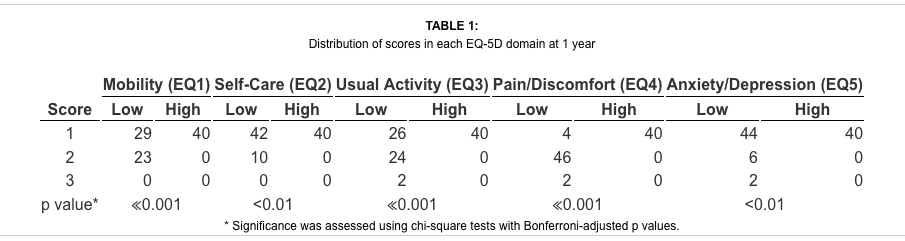

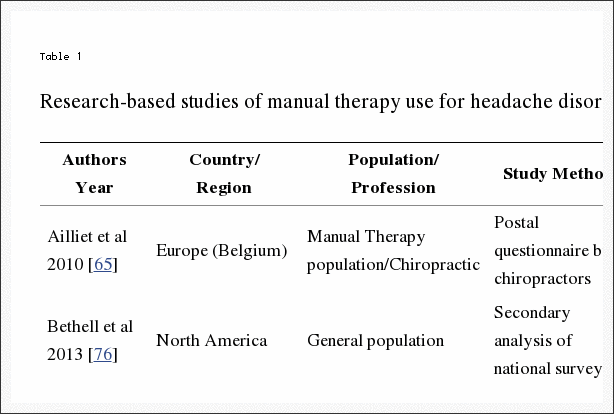

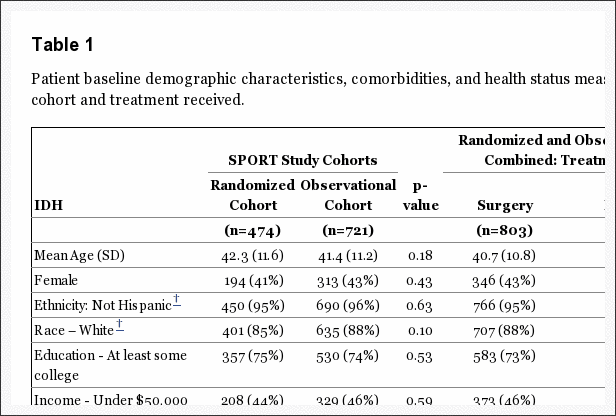

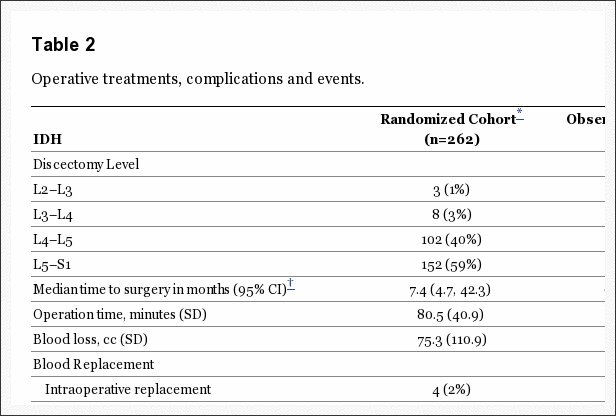

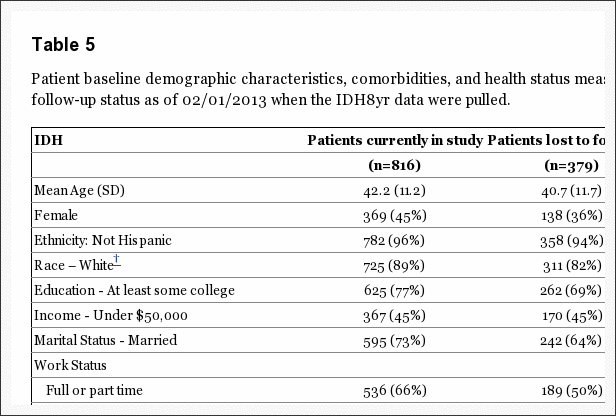

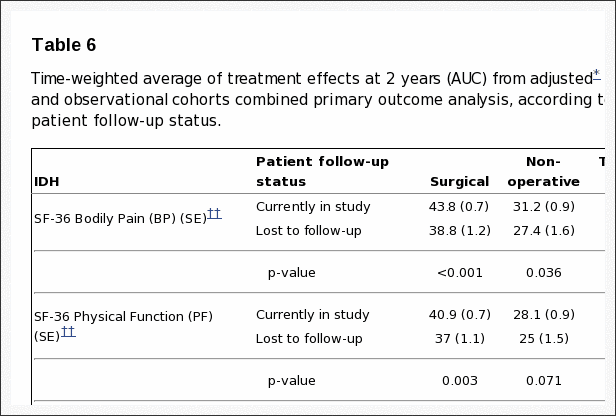

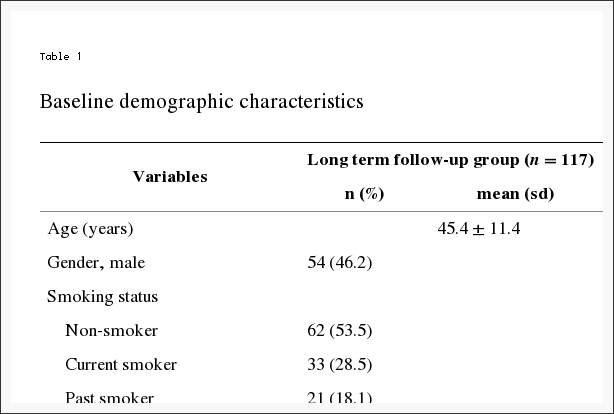

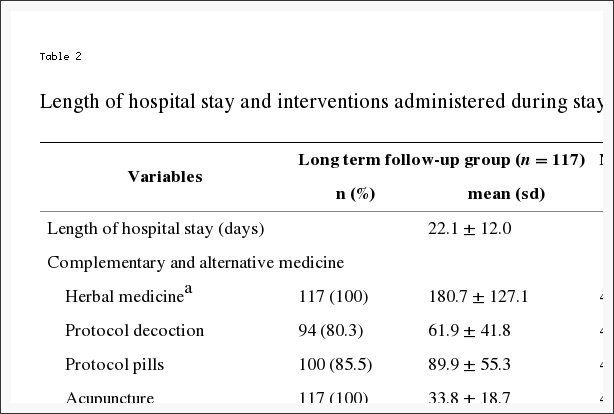

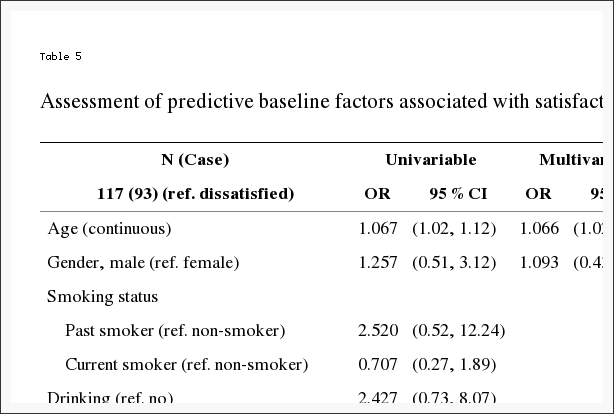

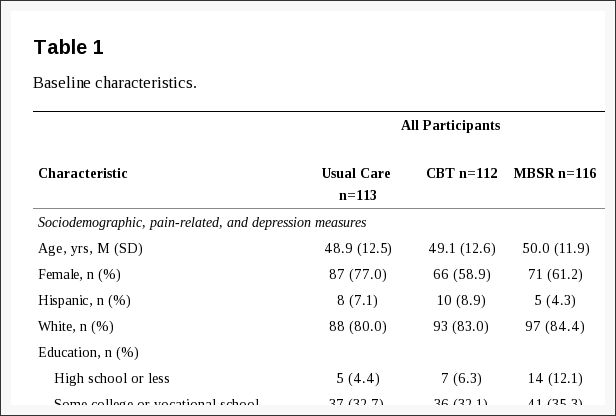

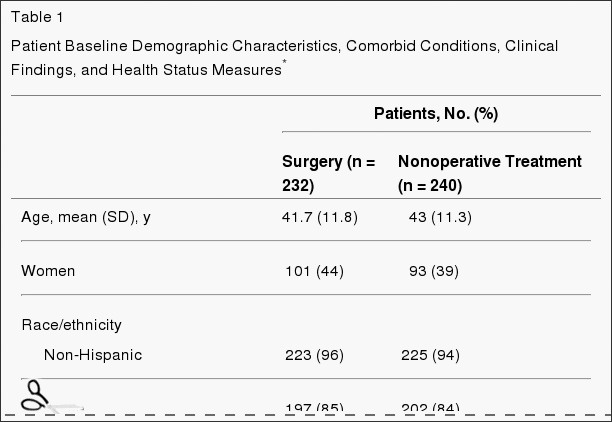

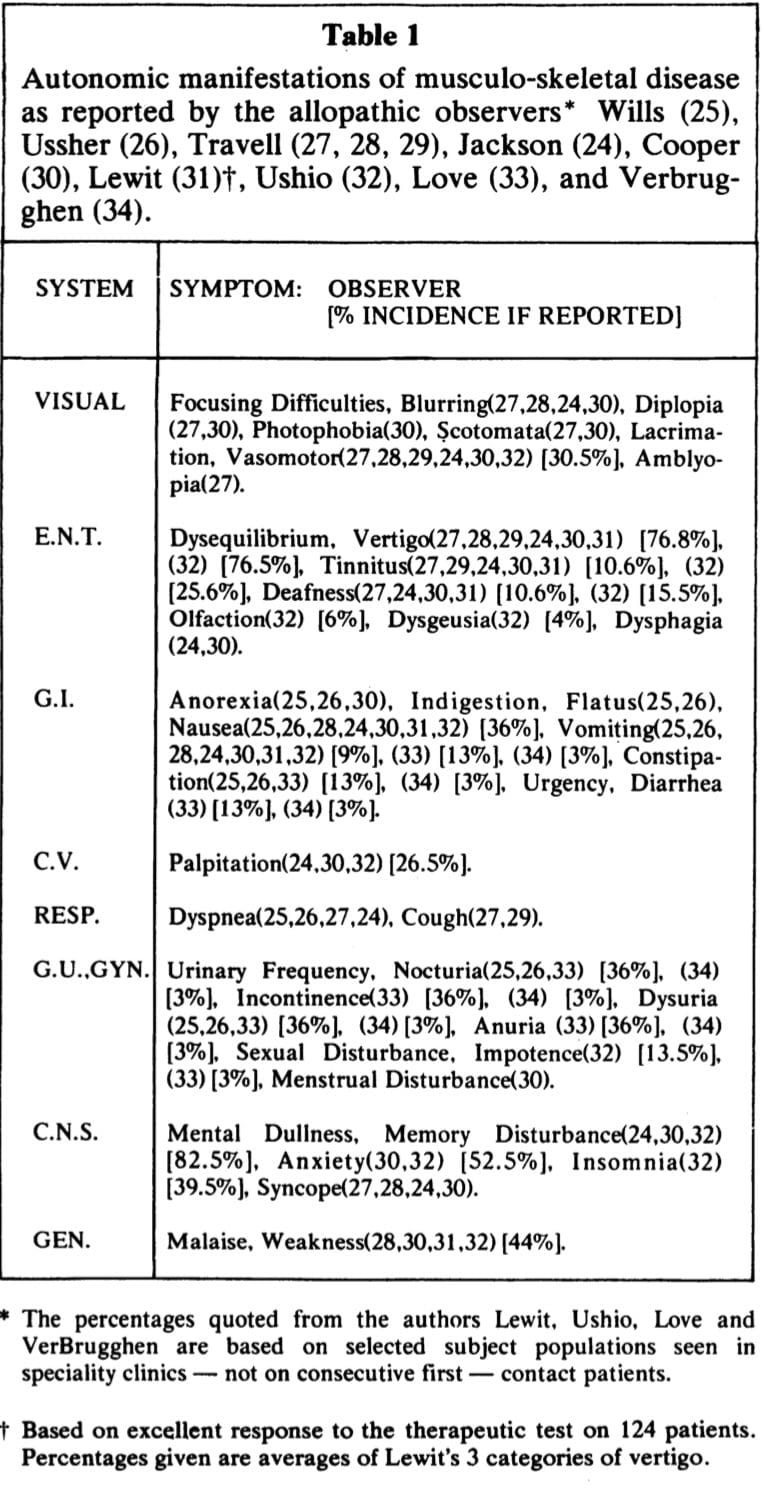

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the sample at baseline. Among all participants, the mean age was 49 years, 66% were female, and 79% reported having had back pain for at least one year without a pain-free week. On average, PHQ-8 scores were at the threshold for mild depressive symptom severity.[32] Mean scores on the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (16-18) were below the various cut-points suggested for clinically relevant catastrophizing (e.g., 24,47 3049). Pain Self-Efficacy Scale scores were somewhat higher on average (about 5 points on the 0-60 scale) in our sample as compared with the primary care patients with low back pain enrolled in an RCT evaluating group CBT in England,[33] and about 15 points higher than among individuals with chronic pain attending a mindfulness-based pain management program in England.[17]

About half of participants randomized to MBSR (50.9%) or CBT (56.3%) attended at least 6 sessions of their assigned treatment; the difference between treatments was not statistically significant (chi-square test, P = 0.42). At baseline, those randomized to MBSR and CBT who completed at least 6 sessions, as compared to those who did not, were significantly older (mean [SD] = 52.2 [10.9] versus 46.5 [13.0] years) and reported significantly lower levels of pain bothersomeness (mean [SD] = 5.7 [1.3] versus 6.4 [1.7]), disability (mean [SD] RDQ = 10.8 [4.5] versus 12.7 [5.0]), depression (mean [SD] PHQ-8 = 5.2 [4.1] versus 6.3 [4.3]), and catastrophizing (mean [SD] PCS = 15.9 [10.3] versus 18.9 [9.8]), and significantly greater pain self-efficacy (mean [SD] PSEQ = 47.8 [8.3] versus 43.2 [10.3]) and pain acceptance (CPAQ-8 total score mean [SD] = 31.3 [6.2] versus 29.0 [6.7]; CPAQ-8 Pain Willingness mean [SD] = 12.3 [4.1] versus 10.9 [4.8]) (all P-values < 0.05). They did not differ significantly on any other variable shown in Table 1.

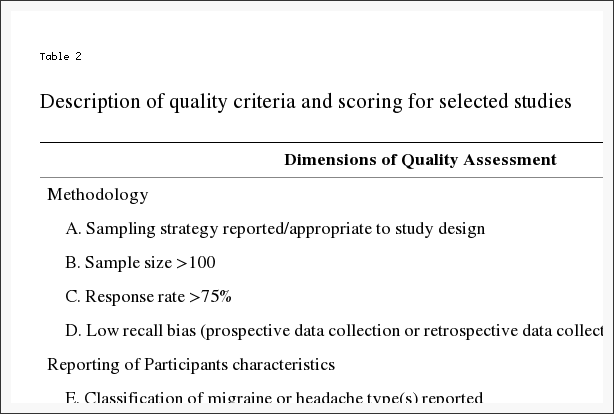

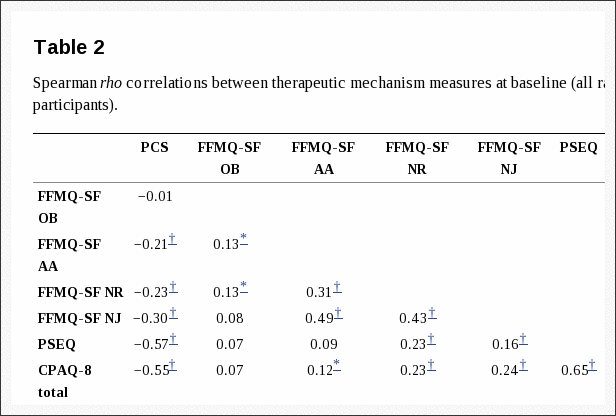

Baseline Associations Between Therapeutic Mechanism Measures

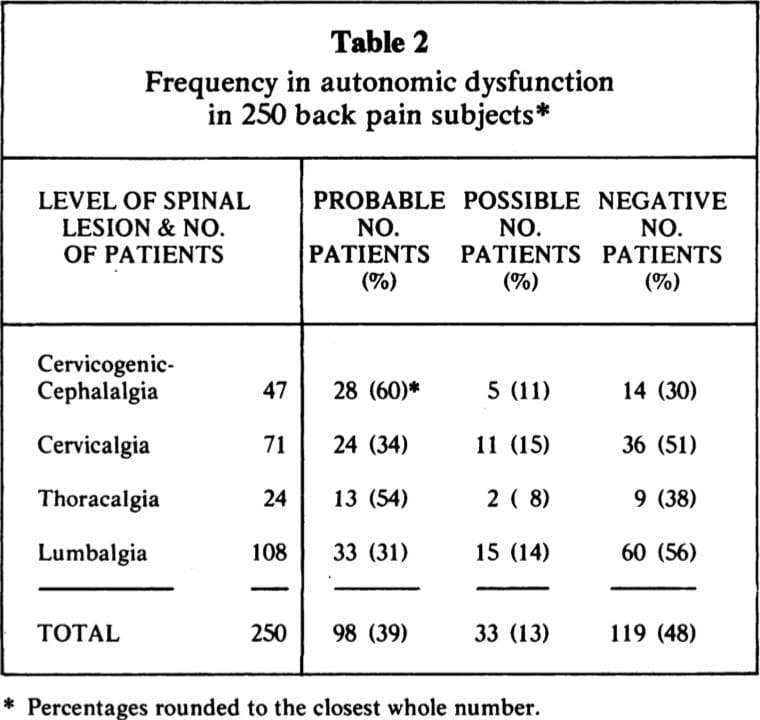

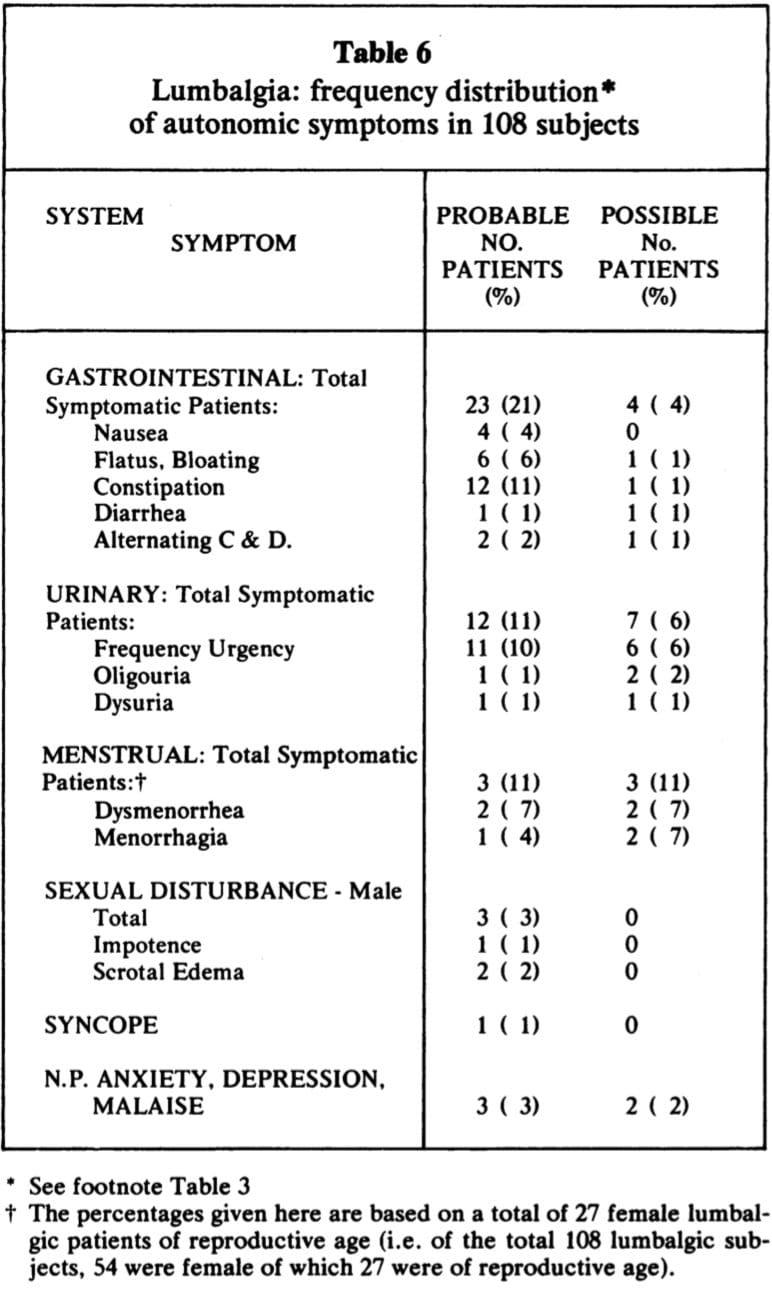

Table 2 shows the Spearman correlations between the therapeutic mechanism measures at baseline. Our hypotheses about the baseline relationships among these measures were confirmed. Catastrophizing was correlated negatively with 3 dimensions of mindfulness (non-reactivity rho = ?0.23, non-judging rho = ?0.30, and acting with awareness rho = ?0.21; all P-values < 0.01), but not associated with the observing dimension of mindfulness (rho = ?0.01). Catastrophizing was also correlated negatively with acceptance (total CPAQ-8 score rho = ?0.55, Pain Willingness subscale rho = ?0.47, Activity Engagement subscale rho = ?0.40) and pain self-efficacy (rho = ?0.57) (all P-values < 0.01). Finally, pain self-efficacy was correlated positively with pain acceptance (total CPAQ-8 score rho = 0.65, Pain Willingness subscale rho = 0.46, Activity Engagement subscale rho = 0.58; all P-values < 0.01).

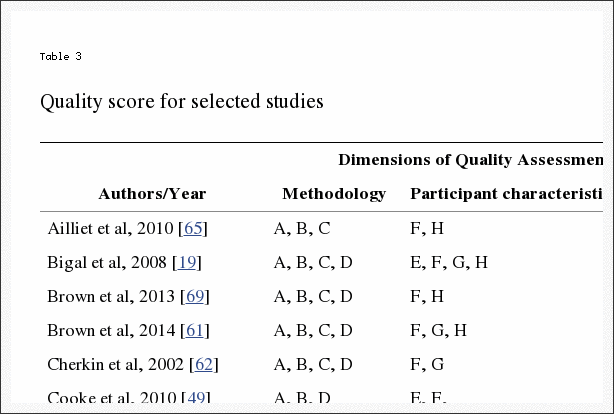

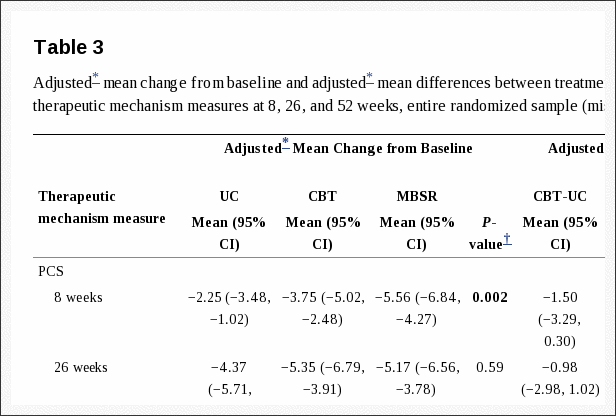

Treatment Group Differences in Changes on Therapeutic Mechanism Measures Among all Randomized Participants

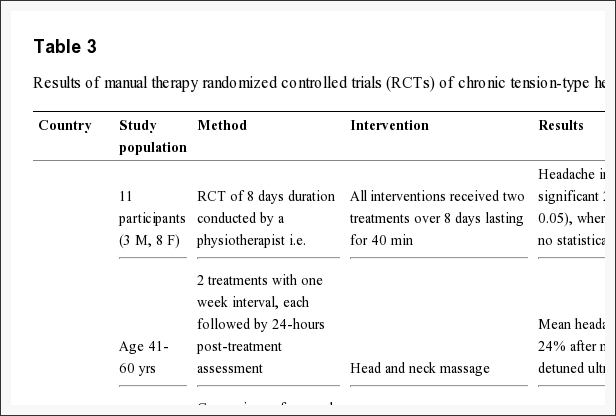

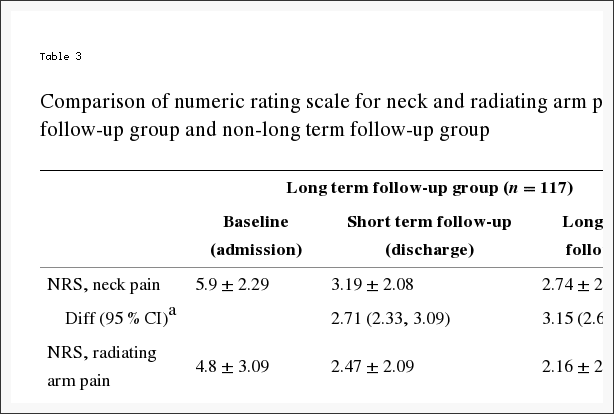

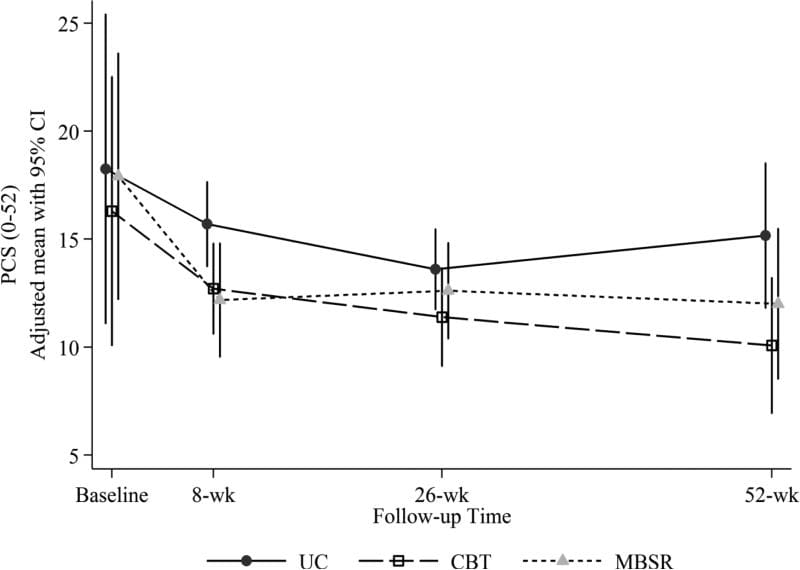

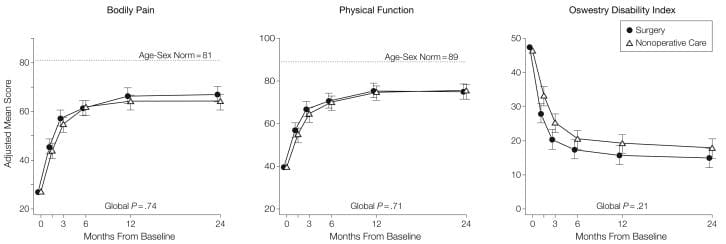

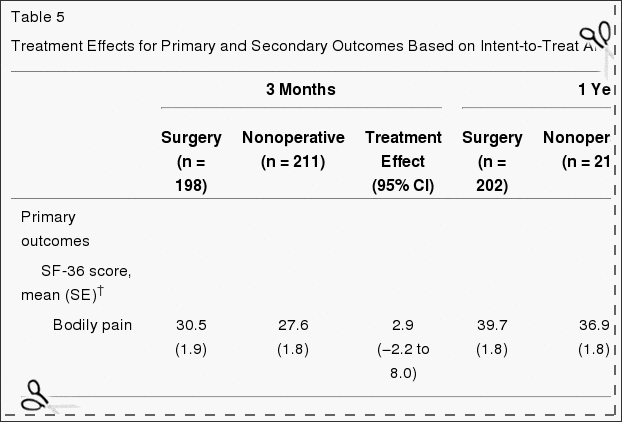

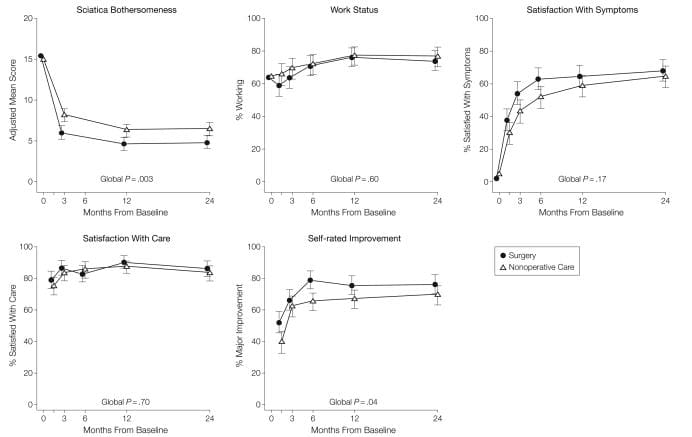

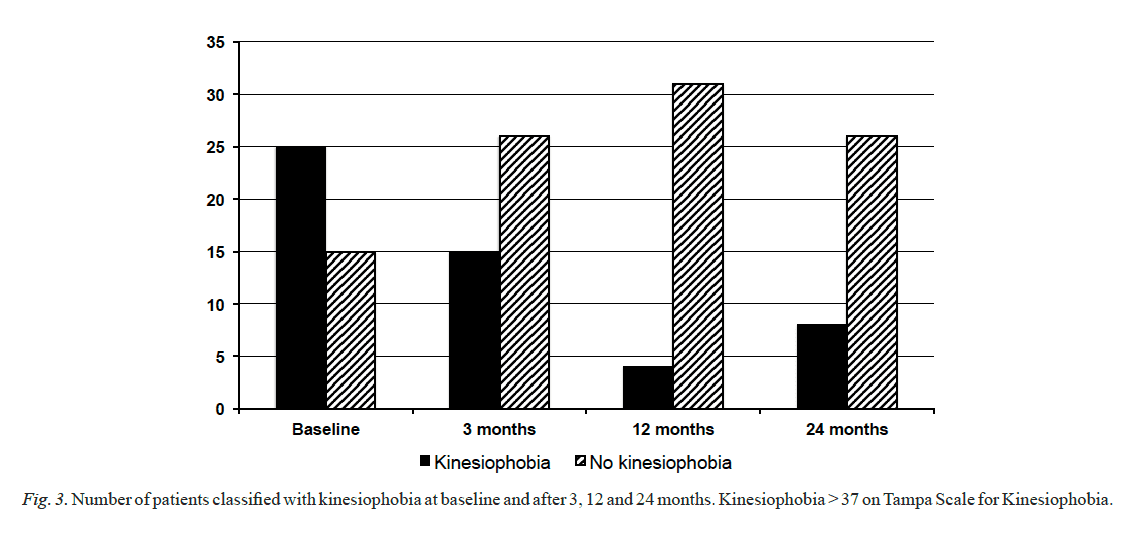

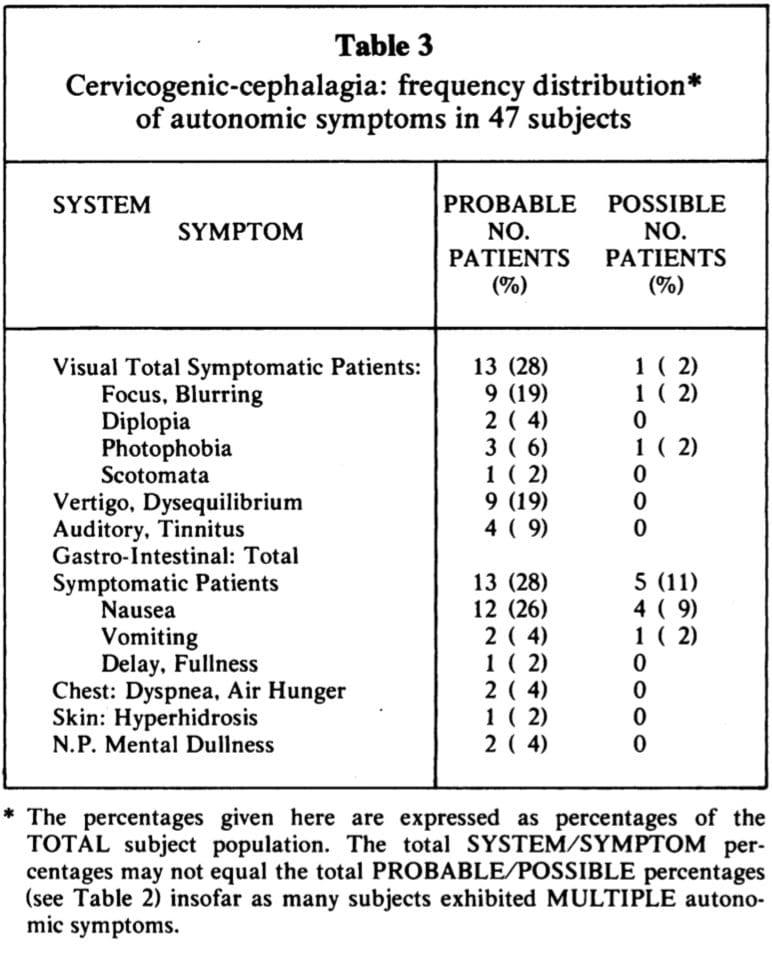

Table 3 shows the adjusted mean changes from baseline in each study group and the adjusted mean differences between treatment groups on the therapeutic mechanism measures at each follow-up in the entire randomized sample. Figure 1 shows the adjusted mean PCS scores for each group at each time point. Contrary to our hypothesis that catastrophizing would decrease more with CBT than with MBSR, catastrophizing (PCS score) decreased significantly more from pre- to post-treatment in the MBSR group than in the CBT group (MBSR versus CBT adjusted mean [95% CI] difference in change = ?1.81 [?3.60, ?0.01]). Catastrophizing also decreased significantly more in MBSR than in UC (MBSR versus UC adjusted mean [95% CI] difference in change = ?3.30 [?5.11, ?1.50]), whereas the difference between CBT and UC was not significant. At 26 weeks, the treatment groups did not differ significantly in change in catastrophizing from baseline. However, at 52 weeks, both the MBSR and the CBT groups showed significantly greater decreases than did the UC group, and there was no significant difference between MBSR and CBT.

Figure 1: Adjusted mean Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) scores (and 95% confidence intervals) at baseline (pre-randomization), 8 weeks (post-treatment), 26 weeks, and 52 weeks for participants randomized to CBT, MBSR, and UC. Estimated means are adjusted for participant age, gender, education, whether or not at least 1 year since week without pain, and baseline RDQ and pain bothersomeness.

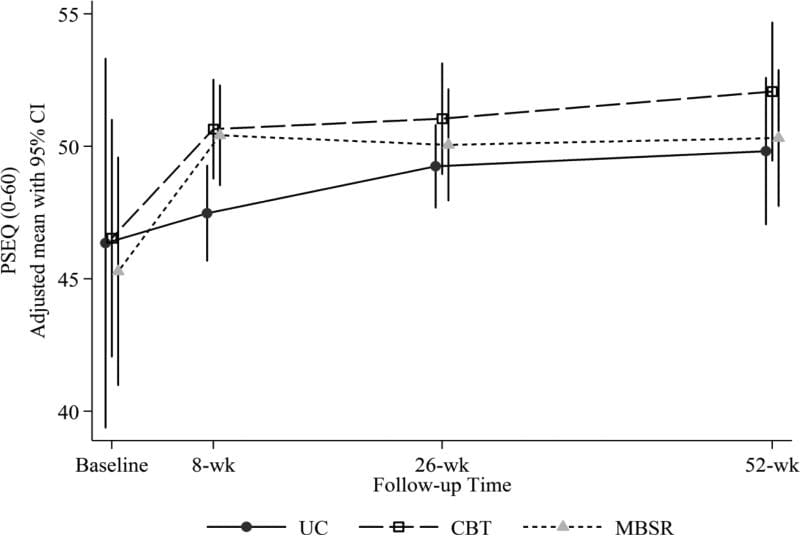

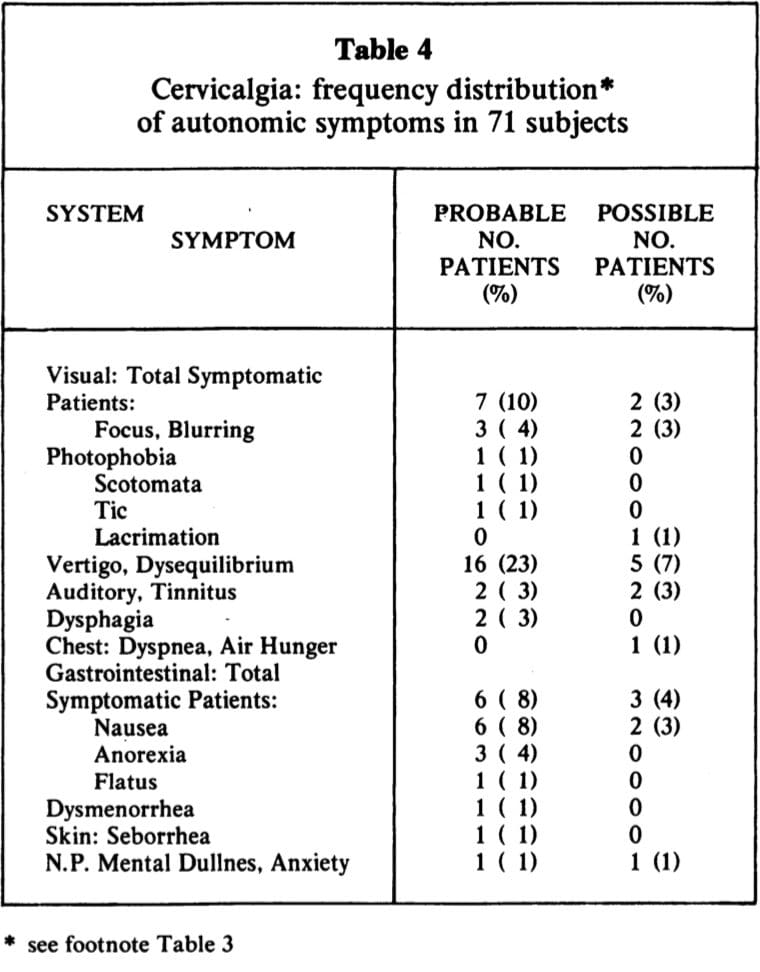

Figure 2 shows the adjusted mean PSEQ scores for each group at each time point. Our hypothesis that self-efficacy would increase more with CBT than with MBSR and with UC was only partially confirmed. Self-efficacy (PSEQ scores) did increase significantly more from pre- to post-treatment with CBT than with UC, but not with CBT relative to the MBSR group, which also increased significantly more than did the UC group (adjusted mean [95% CI] difference in change on PSEQ from baseline for CBT versus UC = 2.69 [0.96, 4.42]; CBT versus MBSR = 0.34 [?1.43, 2.10]; MBSR versus UC = 3.03 [1.23, 4.82]) (Table 3). The omnibus test for differences across groups in self-efficacy change was not significant at 26 or 52 weeks.

Figure 2: Adjusted mean Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ) scores (and 95% confidence intervals) at baseline (pre-randomization), 8 weeks (post-treatment), 26 weeks, and 52 weeks for participants randomized to CBT, MBSR, and UC. Estimated means are adjusted for participant age, gender, education, whether or not at least 1 year since week without pain, and baseline RDQ and pain bothersomeness.

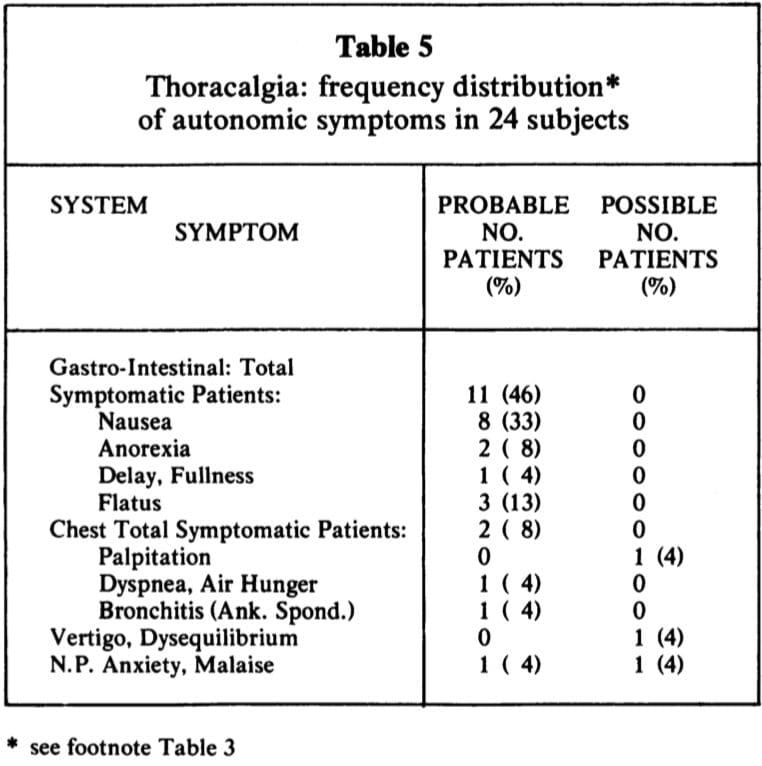

Our hypothesis that acceptance would increase more with MBSR than with CBT and with UC was generally not confirmed. The omnibus test for differences across groups was not significant for the total CPAQ-8 or the Activity Engagement subscale at any time point (Table 3). The test for the Pain Willingness subscale was significant at 52 weeks only, when both the MBSR and CBT groups showed greater increases as compared with UC, but not as compared with each other (adjusted mean [95% CI] difference in change for MBSR versus UC = 1.15 [0.05, 2.24]; CBT versus UC = 1.23 [0.16, 2.30]).

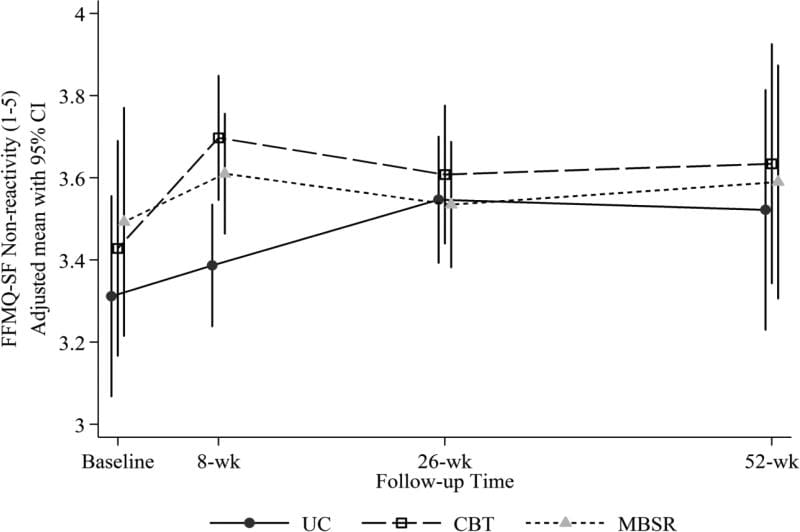

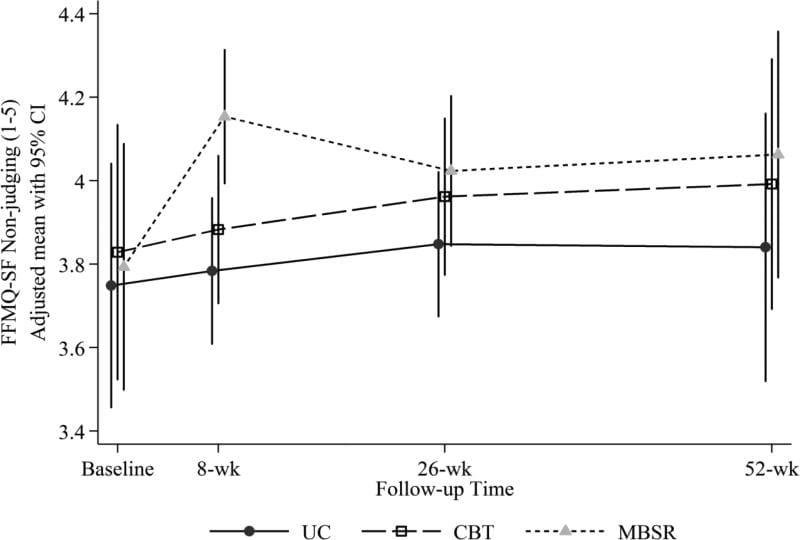

Our hypothesis that mindfulness would increase more with MBSR than with CBT was partially confirmed. Both the MBSR and CBT groups showed greater increases as compared with UC on the FFMQ-SF Non-reactivity scale at 8 weeks (MBSR versus UC = 0.18 [0.01, 0.36]; CBT versus UC = 0.28 [0.10, 0.46]), but differences at later follow-ups were not statistically significant (Table 3, Figure 3). There was a significantly greater increase on the Non-judging scale with MBSR versus CBT (adjusted mean [95% CI] difference in change = 0.29 [0.12, 0.46]) as well as between MBSR and UC (0.32 [0.13, 0.50]) at 8 weeks, but no significant difference between groups at later time points (Figure 4). The omnibus test for differences among groups was not significant for the Acting with Awareness or Observing scales at any time point.

Figure 3: Adjusted mean Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire-Short Form (FFMQ-SF) Non-reactivity scores (and 95% confidence intervals) at baseline (pre-randomization), 8 weeks (post-treatment), 26 weeks, and 52 weeks for participants randomized to CBT, MBSR, and UC. Estimated means are adjusted for participant age, gender, education, whether or not at least 1 year since week without pain, and baseline RDQ and pain bothersomeness.

Figure 4: Adjusted mean Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire-Short Form (FFMQ-SF) Non-judging scores (and 95% confidence intervals) at baseline (pre-randomization), 8 weeks (post-treatment), 26 weeks, and 52 weeks for participants randomized to CBT, MBSR, and UC. Estimated means are adjusted for participant age, gender, education, whether or not at least 1 year since week without pain, and baseline RDQ and pain bothersomeness.

The sensitivity analyses using observed rather than imputed data yielded almost identical results, with 2 minor exceptions. The difference between MBSR and CBT in change in catastrophizing at 8 weeks, although similar in magnitude, was no longer statistically significant due to slight confidence interval changes. Second, the omnibus test for the CPAQ-8 Pain Willingness scale at 52 weeks was no longer statistically significant (P = 0.07).

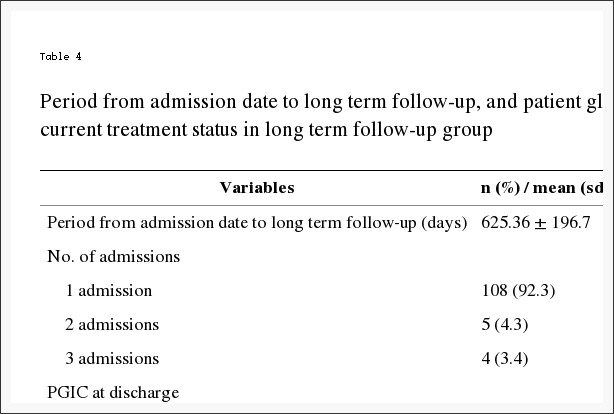

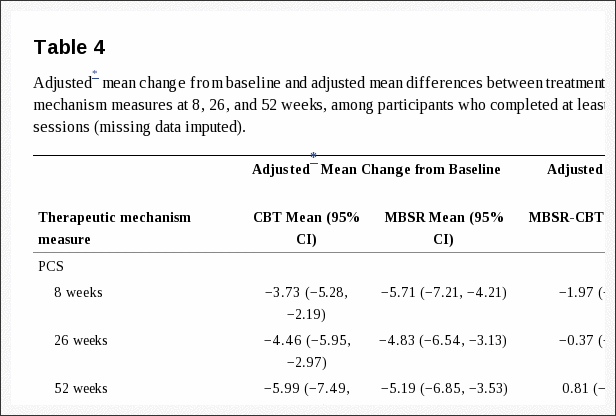

Treatment Group Differences in Changes on Therapeutic Mechanism Measures Among Participants Randomized to CBT or MBSR Who Completed at Least 6 Sessions

Table 4 shows the adjusted mean change from baseline and adjusted mean between-group differences on the therapeutic mechanism measures at 8, 26, and 52 weeks for participants who were randomized to MBSR or CBT and completed 6 or more sessions of their assigned treatment. The differences between MBSR and CBT were similar in size to those in the ITT sample. There were only a few differences in statistical significance of the comparisons. In contrast to the results using the ITT sample, the difference between MBSR and CBT in catastrophizing (PCS) at 8 weeks was no longer statistically significant and at 52 weeks, the CBT group increased significantly more than did the MBSR group on the FFMQ-SF Observing scale (adjusted mean difference in change from baseline for MBSR versus CBT = ?0.30 [?0.53, ?0.07]). The sensitivity analyses using observed rather than imputed data yielded no meaningful differences in results.

Discussion

In this analysis of data from an RCT comparing MBSR, CBT, and UC for CLBP, our hypotheses that MBSR and CBT would differentially affect measures of constructs believed to be therapeutic mechanisms generally were not confirmed. For example, our hypothesis that mindfulness would increase more with MBSR than with CBT was confirmed for only 1 of 4 measured facets of mindfulness (non-judging). Another facet, acting with awareness, increased more with CBT than with MBSR at 26 weeks. Both differences were small. Increased mindfulness after a CBT-based multidisciplinary pain program[10] was reported previously; our findings further support a view that both MBSR and CBT increase mindfulness in the short-term. We found no long-term effects of either treatment relative to UC on mindfulness.

Also contrary to hypothesis, catastrophizing decreased more post-treatment with MBSR than with CBT. However, the difference between treatments was small and not statistically significant at later follow-ups. Both treatments were effective compared with UC in decreasing catastrophizing at 52 weeks. Although previous studies demonstrated reductions in catastrophizing after both CBT[35,48,56,57] and mindfulness-based pain management programs,[17,24,37] ours is the first to demonstrate similar decreases for both treatments, with effects up to 1 year.

Increased self-efficacy has been shown to be associated with improvements in pain intensity and functioning,[6] and an important mediator of CBT benefits.[56] However, contrary to our hypothesis, pain self-efficacy did not increase more with CBT than with MBSR at any time point. Compared with UC, there were significantly greater increases in self-efficacy with both MBSR and CBT post-treatment. These results mirror previous findings of positive effects of CBT, including group CBT for back pain,[33] on self-efficacy.[3,56,57] Little research has examined self-efficacy changes after MBIs for chronic pain, although self-efficacy increased more with MBSR than with usual care for patients with migraines in a pilot study[63] and more with MBSR than with health education for CLBP in an RCT.[37] Our findings add to knowledge in this area by indicating that MBSR has short-term benefits for pain self-efficacy similar to those of CBT.

Prior uncontrolled studies found equivalent increases in pain acceptance after group CBT and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy64 (which, unlike traditional CBT, specifically fosters pain acceptance), and increased acceptance after CBT-based multidisciplinary pain treatment.[1,2] In our RCT, acceptance increased in all groups over time, with only 1 statistically significant difference among the 3 groups across the 3 acceptance measures and 3 follow-up time points (a greater increase with both MBSR and CBT than with UC on the Pain Willingness subscale at 52 weeks). This suggests that acceptance may increase over time regardless of treatment, although this needs to be confirmed in additional research.

Two possibilities could explain our previously-reported findings of generally similar effectiveness of MBSR and CBT for CLBP:[12] (1) the treatment effects on outcomes were due to different, but equally effective, therapeutic mechanisms, or (2) the treatments had similar effects on the same therapeutic mechanisms. Our current findings support the latter view. Both treatments may improve pain, function, and other outcomes through different strategies that decrease individuals� views of their pain as threatening and disruptive and encourage activity participation despite pain. MBSR and CBT differ in content, but both include relaxation techniques (e.g., progressive muscle relaxation in CBT, meditation in MBSR, breathing techniques in both) and strategies to decrease the threat value of pain (education and cognitive restructuring in CBT, accepting experiences without reactivity or judgment in MBSR). Thus, although CBT emphasizes learning skills for managing pain and decreasing negative emotional responses, and MBSR emphasizes mindfulness and meditation, both treatments may help patients relax, react less negatively to pain, and view thoughts as mental processes rather than as accurate representations of reality, thereby resulting in decreased emotional distress, activity avoidance, and pain bothersomeness.

Our analyses also revealed overlap among measures of different constructs believed to mediate the effects of MBSR and CBT on chronic pain outcomes. As hypothesized, prior to treatment, pain catastrophizing was associated negatively with pain self-efficacy, pain acceptance, and 3 dimensions of mindfulness (non-reactivity, non-judging, and acting with awareness), and pain acceptance was associated positively with pain self-efficacy. Pain acceptance and self-efficacy were also associated positively with measures of mindfulness. Our results are consistent with prior observations of negative associations between measures of catastrophizing and acceptance,[15,19,60] negative correlations between measures of catastrophizing and mindfulness,[10,46,18] and positive associations between measures of pain acceptance and mindfulness.[19]

As a group, to the extent that these measures reflect their intended constructs, these findings support a view of catastrophizing as inversely associated with two related constructs that reflect participation in customary activities despite pain but differ in emphasis on disengagement from attempts to control pain: pain acceptance (disengagement from attempts to control pain and participation in activities despite pain) and self-efficacy (confidence in ability to manage pain and participate in customary activities). The similarity of some questionnaire items further supports this view and likely contributes to the observed associations. For example, both the CPAQ-8 and the PSEQ contain items about doing normal activities despite pain. Furthermore, there is an empirical and conceptual basis for a view of catastrophizing (focus on pain with highly negative cognitive and affective responses) as also inversely associated with mindfulness (i.e., awareness of stimuli without judgment or reactivity), and for viewing mindfulness as consistent with, but distinct from, acceptance and self-efficacy. Further work is needed to clarify the relationships between these theoretical constructs and the extent to which their measures assess (a) constructs that are related but theoretically and clinically distinct versus (b) different aspects of an overarching theoretical construct.

It remains possible that MBSR and CBT differentially affect important mediators not assessed in this study. Our results highlight the need for further research to more definitively identify the mediators of the effects of MBSR and CBT on different pain outcomes, develop measures that assess these mediators most comprehensively and efficiently, better understand the relationships among therapeutic mechanism variables in affecting outcomes (e.g., decreased catastrophizing may mediate the effect of mindfulness on disability[10]), and refine psychosocial treatments to more effectively and efficiently impact these mediators. Research is also needed to identify patient characteristics associated with response to different psychosocial interventions for chronic pain.

Several study limitations warrant discussion. Participants had low baseline levels of psychosocial distress (e.g., catastrophizing, depression) and we studied group CBT, which has demonstrated efficacy,[33,40,55] resource-efficiency, and potential social benefits, but which may be less effective than individual CBT.[36,66] The results may not generalize to more distressed populations (e.g., pain clinic patients), which would have more room to improve on measures of maladaptive functioning and greater potential for treatments to differentially affect these measures, or to comparisons of MBSR with individual CBT.

Only somewhat over half of the participants randomized to MBSR or CBT attended at least 6 of the 8 sessions. Results could differ in studies with higher rates of treatment adherence; however, our results in �as-treated� analyses generally mirrored those of ITT analyses. Treatment adherence has been shown to be associated with benefits from both CBT for chronic back pain[31] and MBSR.[9] Research is needed to identify ways to increase MBSR and CBT session attendance, and to determine whether treatment effects on therapeutic mechanism and outcome variables are strengthened with greater adherence and practice.

Finally, our measures may not have adequately captured the intended constructs. For example, our mindfulness and pain acceptance measures were short forms of original measures; although these short forms have demonstrated reliability and validity, the original measures or other measures of these constructs might perform differently. Lauwerier et al.[34] note several problems with the CPAQ-8 Pain Willingness scale, including under-representation of pain willingness items. Furthermore, pain acceptance is measured differently across different pain acceptance measures, possibly reflecting differences in definitions.[34]

In sum, this is the first study to examine relationships among measures of key hypothesized mechanisms of MBSR and CBT for chronic pain – mindfulness and pain catastrophizing, self-efficacy, and acceptance – and to examine changes in these measures among participants in an RCT comparing MBSR and CBT for chronic pain. The catastrophizing measure was inversely associated with moderately inter-related measures of acceptance, self-efficacy, and mindfulness. In this sample of individuals with generally low levels of psychosocial distress at baseline, MBSR and CBT had similar short- and long-term effects on these measures. Measures of catastrophizing, acceptance, self-efficacy, and mindfulness may tap different aspects of a continuum of cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses to pain, with catastrophizing and activity avoidance at one end of the continuum and continued participation in usual activities and lack of negative cognitive and affective reactivity to pain at the other. Both MBSR and CBT may have therapeutic benefits by helping individuals with chronic pain shift from the former to the latter. Our results suggest the potential value of refining both measures and models of mechanisms of psychosocial pain treatments to more comprehensively and efficiently capture key constructs important in adaptation to chronic pain.

Summary

MBSR and CBT had similar short- and long-term effects on measures of mindfulness and pain catastrophizing, self-efficacy, and acceptance.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Complementary & Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AT006226. Preliminary results related to this study were presented in a poster at the 34th annual meeting of the American Pain Society, Palm Springs, May 2015 (Turner, J., Sherman, K., Anderson, M., Balderson, B., Cook, A., and Cherkin, D.: Catastrophizing, pain self-efficacy, mindfulness, and acceptance: Relationships and changes among individuals receiving CBT, MBSR, or usual care for chronic back pain).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: Judith Turner receives royalties from PAR, Inc. on sales of the Chronic Pain Coping Inventory (CPCI) and CPCI/Survey of Pain Attitudes (SOPA) score report software. The other authors report no conflicts of interest.

In conclusion, stress is part of an essential response necessary to keep our body’s on edge in the case of danger, however, constant stress when there’s no real danger can become a real issue for many individuals, especially when symptoms of low back pain, among others begin to manifest. The purpose of the article above was to determine the effectiveness of stress management in the treatment of low back pain. Ultimately, stress management was concluded to help with treatment. Information referenced from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic as well as to spinal injuries and conditions. To discuss the subject matter, please feel free to ask Dr. Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

Curated by Dr. Alex Jimenez

Additional Topics: Back Pain

According to statistics, approximately 80% of people will experience symptoms of back pain at least once throughout their lifetimes. Back pain is a common complaint which can result due to a variety of injuries and/or conditions. Often times, the natural degeneration of the spine with age can cause back pain. Herniated discs occur when the soft, gel-like center of an intervertebral disc pushes through a tear in its surrounding, outer ring of cartilage, compressing and irritating the nerve roots. Disc herniations most commonly occur along the lower back, or lumbar spine, but they may also occur along the cervical spine, or neck. The impingement of the nerves found in the low back due to injury and/or an aggravated condition can lead to symptoms of sciatica.

IMPORTANT TOPIC: EXTRA EXTRA: A Healthier You!

OTHER IMPORTANT TOPICS: EXTRA: Sports Injuries? | Vincent Garcia | Patient | El Paso, TX Chiropractor

Case 7: Mr. V. presented with acute lumbo-

Case 7: Mr. V. presented with acute lumbo-