Non-Invasive Treatment Modalities for Back Pain

Attributed from a personal perspective, as a practicing chiropractor with experience on a variety of spinal injuries and conditions, back pain is one of the most common health issues reported among the general population, affecting about 8 out of 10 individuals at some point throughout their lives. While many different types of treatments are currently available to help improve the symptoms of back pain, health care based on clinical and experimental evidence has caused an impact on the type of treatment individuals will receive for their back pain. Many patients in health care are turning to non-invasive treatment modalities for their back pain as a result of growing evidence associated with its safety and effectiveness.

On a further note, non-invasive treatment modalities are defined as conservative procedures which do not require incision into the body, where no break in the skin is created and there is no contact with the mucosa or internal body cavity beyond a natural or artificial body orifice, or the removal of tissue. The clinical and experimental methods and results of a variety of non-invasive treatment modalities on back pain have been described and discussed in detail below.

Abstract

At present, there is an increasing international trend towards evidence-based health care. The field of low back pain (LBP) research in primary care is an excellent example of evidence-based health care because there is a huge body of evidence from randomized trials. These trials have been summarized in a large number of systematic reviews. This paper summarizes the best available evidence from systematic reviews conducted within the framework of the Cochrane Back Review Group on non-invasive treatments for non-specific LBP. Data were gathered from the latest Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 2. The Cochrane reviews were updated with additional trials, if available. Traditional NSAIDs, muscle relaxants, and advice to stay active are effective for short-term pain relief in acute LBP. Advice to stay active is also effective for long-term improvement of function in acute LBP. In chronic LBP, various interventions are effective for short-term pain relief, i.e. antidepressants, COX2 inhibitors, back schools, progressive relaxation, cognitive�respondent treatment, exercise therapy, and intensive multidisciplinary treatment. Several treatments are also effective for short-term improvement of function in chronic LBP, namely COX2 inhibitors, back schools, progressive relaxation, exercise therapy, and multidisciplinary treatment. There is no evidence that any of these interventions provides long-term effects on pain and function. Also, many trials showed methodological weaknesses, effects are compared to placebo, no treatment or waiting list controls, and effect sizes are small. Future trials should meet current quality standards and have adequate sample size.

Keywords: Non-specific low back pain, Non-invasive treatment, Primary care, Effectiveness, Evidence review

Introduction

Low back pain is most commonly treated in primary health care settings. Clinical management of acute as well as chronic low back pain (LBP) varies substantially among health care providers. Also, many different primary health care professionals are involved in the management of LBP, such as general practitioners, physical therapists, chiropractors, osteopaths, manual therapists, and others. There is a need to increase consistency in the management of LBP across professions.

At present, there is an increasing international trend towards evidence-based health care. Within the framework of evidence-based health care, clinicians should conscientiously, explicitly, and judiciously use the best current evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. The field of LBP research in primary care is an excellent example of evidence-based health care because there is a huge body of evidence. At present, more than 500 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been published, evaluating all types of conservative and alternative treatments for LBP that are commonly used in primary care. These trials have been summarized in a large number of systematic reviews. The Cochrane Back Review Group (CBRG) offers a framework for conducting and publishing systematic reviews in the fields of back and neck pain. However, method guidelines have also been developed and published by the CBRG to improve the quality of reviews in this field and to facilitate comparison across reviews and enhance consistency among reviewers. This paper summarizes the best available evidence from systematic reviews conducted within the framework of the CBRG on non-invasive treatments for non-specific LBP.

Objectives

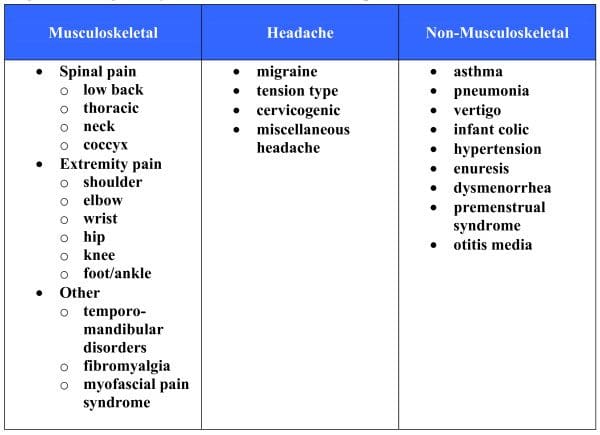

To determine the effectiveness of non-invasive (pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical) interventions compared to placebo (or sham treatment, no intervention and waiting list control) or other interventions for acute, subacute, and chronic non-specific LBP. Trials comparing various types of the same interventions (e.g. various types of NSAIDs or various types of exercises) were excluded. The evidence on complementary and alternative medicine interventions (acupuncture, botanical medicines, massage, and neuroreflexotherapy) has been published elsewhere. Evidence on surgical and other invasive interventions for LBP will be presented in another paper in the same issue of the European Spine Journal.

Methods

The results of systematic reviews conducted within the framework of the CBRG were used. Most of these reviews were published, but preliminary results from one Cochrane review on patient education (A. Engers et al., submitted for publication) that has been submitted for publication were also used. Because no Cochrane review was available, we used two recently published systematic reviews for the evidence summary on antidepressants. The Cochrane review on work conditioning, work hardening, and functional restoration was not taken into account because all trials included in this review were also included in the reviews on exercise therapy and multidisciplinary treatment. The Cochrane reviews were updated with additional trials, if available, using Clinical Evidence as source (www.clinicalevidence.com). This manuscript consists of two parts: one on evidence of pharmaceutical interventions and the other on evidence of non-pharmaceutical interventions for non-specific LBP.

Search Strategy and Study Selection

The following search strategy was used in the Cochrane reviews:

- A computer aided search of the Medline and Embase databases since their beginning.

- A search of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Central).

- Screening references given in relevant systematic reviews and identified trials.

- Personal communication with content experts in the field.

Two reviewers independently applied the inclusion criteria to select the potentially relevant trials from the titles, abstracts, and keywords of the references retrieved by the literature search. Articles for which disagreement existed, and articles for which title, abstract, and keywords provided insufficient information for a decision on selection were obtained to assess whether they met the inclusion criteria. A consensus method was used to resolve disagreements between the two reviewers regarding the inclusion of studies. A third reviewer was consulted if disagreements were not resolved in the consensus meeting.

Inclusion Criteria

Study design. RCTs were included in all reviews.

Participants. Participants of trials that were included in the systematic reviews usually had acute (less than 6 weeks), subacute (6�12 weeks), and/or chronic (12 weeks or more) LBP. All reviews included patients with non-specific LBP.

Interventions. All reviews included one specific intervention. Typically any comparison group was allowed, but comparisons with no treatment/placebo/waiting list controls and other interventions were separately presented.

Outcomes. The outcome measures included in the systematic reviews were outcomes of symptoms (e.g. pain), overall improvement or satisfaction with treatment, function (e.g. back-specific functional status), well-being (e.g. quality of life), disability (e.g. activities of daily living, work absenteeism), and side effects. Results were separately presented for short-term and long-term follow-up.

Methodological Quality Assessment

In most reviews, the methodological quality of trials included in the reviews was assessed using the criteria recommended by the CBRG. The studies were not blinded for authors, institutions, or the journals in which the studies were published. The criteria were: (1) adequate allocation concealment, (2) adequate method of randomization, (3) similarity of baseline characteristics, (4) blinding of patients, (5) blinding of care provider, (6) equal co-interventions, (7) adequate compliance, (8) identical timing of outcome assessment, (9) blinded outcome assessment, (10) withdrawals and drop outs adequate, and (11) intention-to-treat analysis. All items were scored as positive, negative, or unclear. High quality was typically defined as fulfilling 6 or more of the 11 quality criteria. We refer readers to the original Cochrane reviews for details of the quality of trials.

Data Extraction

The data that were extracted and presented in tables included characteristics of participants, interventions, outcomes, and results. We refer readers to the original Cochrane reviews for summaries of trial data.

Data Analysis

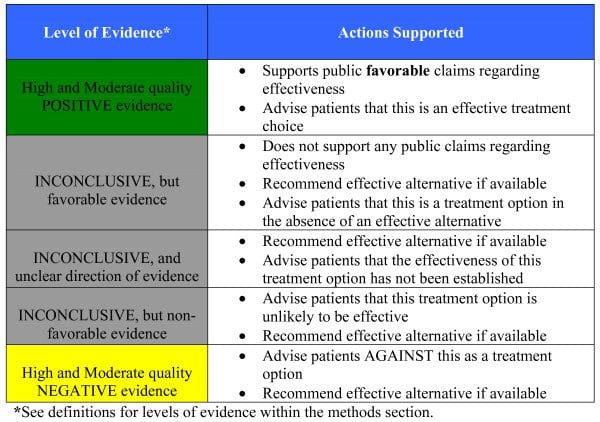

Some reviews conducted a meta-analysis using statistical methods to analyse and summarize the data. If relevant valid data were lacking (data were too sparse or of inadequate quality) or if data were statistically too heterogeneous (and the heterogeneity could not be explained), statistical pooling was avoided. In these cases, reviewers performed a qualitative analysis. In the qualitative analyses, various levels of evidence were used that took into account the participants, interventions, outcomes, and methodological quality of the original studies. If only a subset of available trials provided sufficient data for inclusion in a meta-analysis (e.g. only some trials reported standard deviations), both a quantitative and qualitative analysis was used.

Dr. Alex Jimenez’s Insight

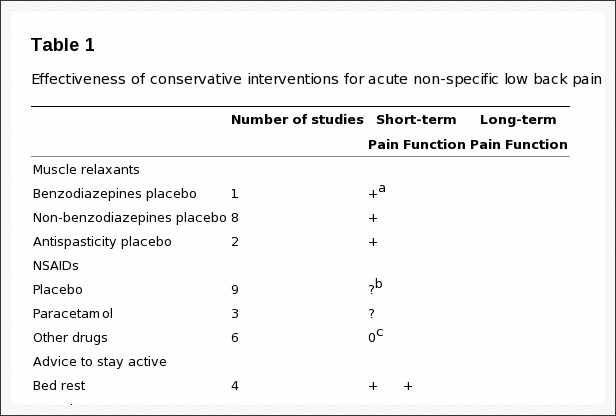

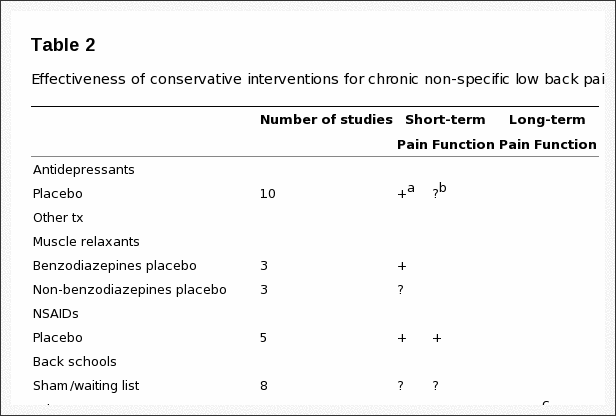

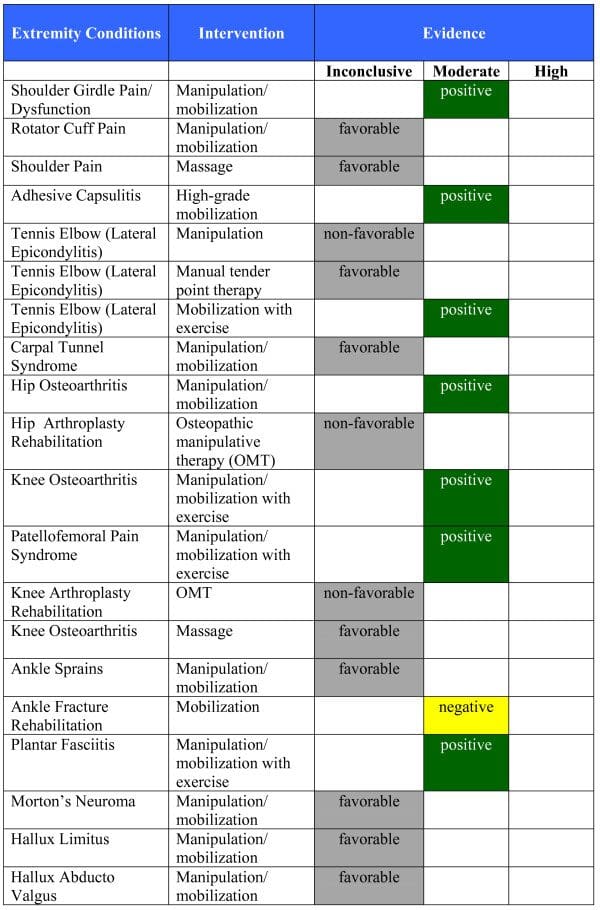

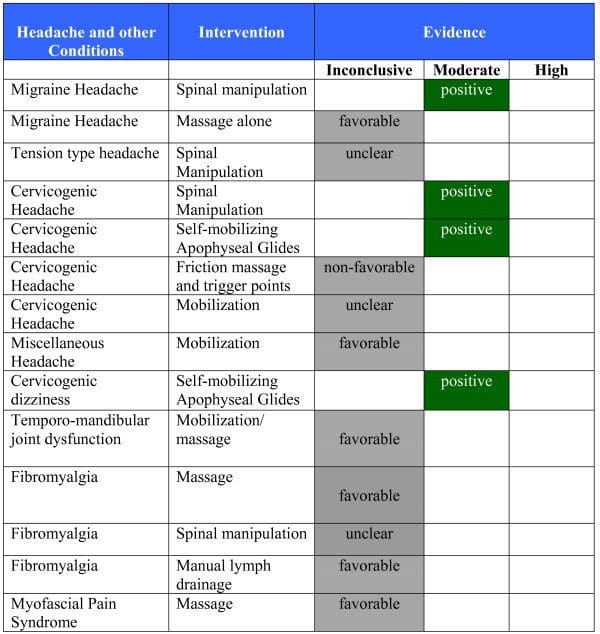

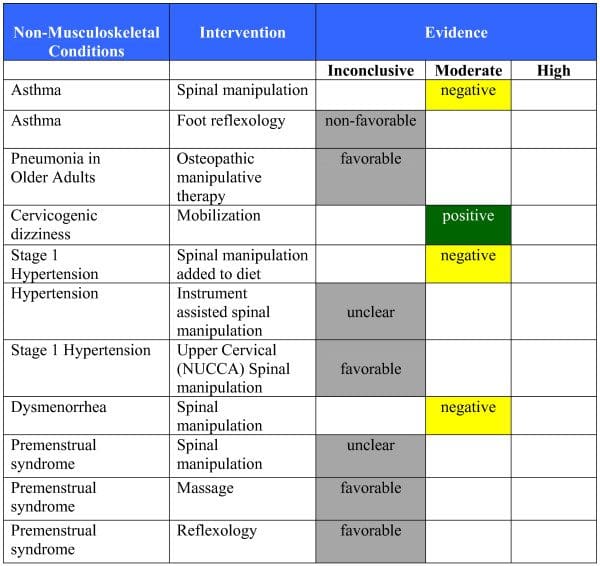

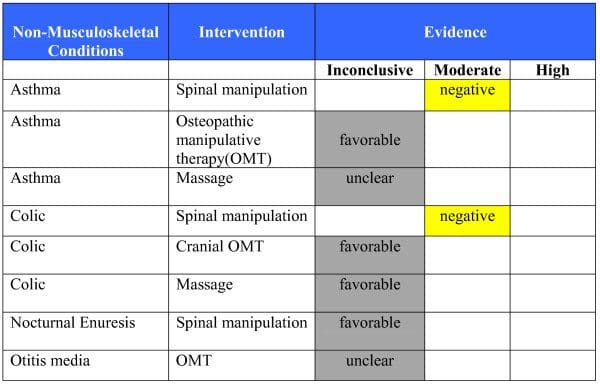

The purpose of the following research study was to determine which of the various non-invasive treatment modalities used could be safe and most effective towards the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of acute, subacute and chronic non-specific low back pain, as well as general back pain. All of the systematic reviews included participants with some type of non-specific low back pain, or LBP, where each received health care for one specific intervention. The outcome measures included in the systematic reviews were based on symptoms, overall improvement or satisfaction with treatment, function, well-being, disability and side effects. The data of the results was extracted and presented in Tables 1 and 2. The researchers of the study performed a qualitative analysis of all the presented clinical and experimental data before demonstrating it in this article. As a healthcare professional, or patient with back pain, the information in this research study may help determine which non-invasive treatment modality should be considered to achieve the desired recovery outcome measures.

Results

Pharmaceutical Interventions

Antidepressants

There are three reasons for using antidepressants in the treatment of LBP. The first reason is that chronic LBP patients often also cope with depression, and treatment with antidepressants may elevate mood and increase pain tolerance. Second, many antidepressant drugs are sedating, and it has been suggested that part of their value for managing chronic pain syndromes simply could be improving sleep. The third reason for the use of antidepressants in chronic LBP patients is their supposed analgesic action, which occurs at lower doses than the antidepressant effect.

Effectiveness of antidepressants for acute LBP No trials were identified.

Effectiveness of antidepressants for chronic LBP Antidepressants versus placebo. We found two systematic reviews including a total of nine trials. One review found that antidepressants significantly increased pain relief compared with placebo but found no significant difference in functioning [pain: standardized mean difference (SMD) 0.41, 95% CI 0.22�0.61; function: SMD 0.24, 95% CI -0.21 to +0.69]. The other review did not statistically pool data but had similar results.

Adverse effects Adverse effects of antidepressants include dry mouth, drowsiness, constipation, urinary retention, orthostatic hypotension, and mania. One RCT found that the prevalence of dry mouth, insomnia, sedation, and orthostatic symptoms was 60�80% with tricyclic antidepressants. However, rates were only slightly lower in the placebo group and none of the differences were significant. In many trials, the reporting of side effects was insufficient.

Muscle Relaxants

The term �muscle relaxants� is very broad and includes a wide range of drugs with different indications and mechanisms of action. Muscle relaxants can be divided into two main categories: antispasmodic and antispasticity medications.

Antispasmodics are used to decrease muscle spasm associated with painful conditions such as LBP. Antispasmodics can be subclassified into benzodiazepines and non-benzodiazepines. Benzodiazepines (e.g. diazepam, tetrazepam) are used as anxiolytics, sedatives, hypnotics, anticonvulsants, and/or skeletal muscle relaxants. Non-benzodiazepines include a variety of drugs that can act at the brain stem or spinal cord level. The mechanisms of action with the central nervous system are still not completely understood.

Antispasticity medications are used to reduce spasticity that interferes with therapy or function, such as in cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis, and spinal cord injuries. The mechanism of action of the antispasticity drugs with the peripheral nervous system (e.g. dantrolene sodium) is the blockade of the sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium channel. This reduces calcium concentration and diminishes actin�myosin interaction.

Effectiveness of muscle relaxants for acute LBP Benzodiazepines versus placebo. One study showed that there is limited evidence (one trial; 50 people) that an intramuscular injection of diazepam followed by oral diazepam for 5 days is more effective than placebo for patients with acute LBP on short-term pain relief and better overall improvement, but is associated with substantially more central nervous system side effects.

Non-benzodiazepines versus placebo. Eight studies were identified. One high quality study on acute LBP showed that there is moderate evidence (one trial; 80 people) that a single intravenous injection of 60 mg orphenadrine is more effective than placebo in immediate relief of pain and muscle spasm for patients with acute LBP.

Three high quality and one low quality trial showed that there is strong evidence (four trials; 294 people) that oral non-benzodiazepines are more effective than placebo for patients with acute LBP on short-term pain relief, global efficacy, and improvement of physical outcomes. The pooled RR and 95% CIs for pain intensity was 0.80 (0.71�0.89) after 2�4 days (four trials; 294 people) and 0.58 (0.45�0.76) after 5�7 days follow-up (three trials; 244 people). The pooled RR and 95% CIs for global efficacy was 0.49 (0.25�0.95) after 2�4 days (four trials; 222 people) and 0.68 (0.41�1.13) after 5�7 days follow-up (four trials; 323 people).

Antispasticity drugs versus placebo. Two high quality trials showed that there is strong evidence (two trials; 220 people) that antispasticity muscle relaxants are more effective than placebo for patients with acute LBP on short-term pain relief and reduction of muscle spasm after 4 days. One high quality trial also showed moderate evidence on short-term pain relief, reduction of muscle spasm, and overall improvement after 10 days.

Effectiveness of muscle relaxants for chronic LBP Benzodiazepines versus placebo. Three studies were identified. Two high quality trials on chronic LBP showed that there is strong evidence (two trials; 222 people) that tetrazepam 50 mg t.i.d. is more effective than placebo for patients with chronic LBP on short-term pain relief and overall improvement. The pooled RRs and 95% CIs for pain intensity were 0.82 (0.72�0.94) after 5�7 days follow-up and 0.71 (0.54�0.93) after 10�14 days. The pooled RR and 95% CI for overall improvement was 0.63 (0.42�0.97) after 10�14 days follow-up. One high quality trial showed that there is moderate evidence (one trial; 50 people) that tetrazepam is more effective than placebo on short-term decrease of muscle spasm.

Non-benzodiazepines versus placebo. Three studies were identified. One high quality trial showed that there is moderate evidence (one trial; 107 people) that flupirtin is more effective than placebo for patients with chronic LBP on short-term pain relief and overall improvement after 7 days, but not on reduction of muscle spasm. One high quality trial showed that there is moderate evidence (one trial; 112 people) that tolperisone is more effective than placebo for patients with chronic LBP on short-term overall improvement after 21 days, but not on pain relief and reduction of muscle spasm.

Adverse effects Strong evidence from all eight trials on acute LBP (724 people) showed that muscle relaxants are associated with more total adverse effects and central nervous system adverse effects than placebo, but not with more gastrointestinal adverse effects; RRs and 95% CIs were 1.50 (1.14�1.98), 2.04 (1.23�3.37), and 0.95 (0.29�3.19), respectively. The most commonly and consistently reported adverse events involving the central nervous system were drowsiness and dizziness. For the gastrointestinal tract this was nausea. The incidence of other adverse events associated with muscle relaxants was negligible.

NSAIDs

The rationale for the treatment of LBP with NSAIDs is based both on their analgesic potential and their anti-inflammatory action.

Effectiveness of NSAIDs for acute LBP NSAIDs versus placebo. Nine studies were identified. Two studies reported on LBP without radiation, two on sciatica, and the other five on a mixed population. There was conflicting evidence that NSAIDs provide better pain relief than placebo in acute LBP. Six of the nine studies which compared NSAIDs with placebo for acute LBP reported dichotomous data on global improvement. The pooled RR for global improvement after 1 week using the fixed effects model was 1.24 (95% CI 1.10�1.41), indicating a statistically significant effect in favour of NSAIDs compared to placebo. The pooled RR (three trials) for analgesic use using the fixed effects model was 1.29 (95% CI 1.05�1.57), indicating significantly less use of analgesics in the NSAIDs group.

NSAIDs versus paracetamol/acetaminophen. There were no differences between NSAIDs and paracetamol reported in two studies, but one study reported better outcomes for two of the four types of NSAIDs. There is conflicting evidence that NSAIDs are more effective than paracetamol for acute LBP.

NSAIDs versus other drugs. Six studies reported on acute LBP, of which five did not find any differences between NSAIDs and narcotic analgesics or muscle relaxants. Group sizes in these studies ranged from 19 to 44 and, therefore, these studies simply may have lacked power to detect a statistically significant difference. There is moderate evidence that NSAIDs are not more effective than other drugs for acute LBP.

Effectiveness of NSAIDs for chronic LBP NSAIDs versus placebo. One small cross-over study (n=37) found that naproxen sodium 275 mg capsules (two capsules b.i.d.) decreased pain more than placebo at 14 days.

COX2 inhibitors versus placebo. Four additional trials were identified. There is strong evidence that COX2 inhibitors (etoricoxib, rofecoxib and valdecoxib) decreased pain and improved function compared with placebo at 4 and 12 weeks, but effects were small.

Adverse effects NSAIDs may cause gastrointestinal complications. Seven of the nine studies which compared NSAIDs with placebo for acute LBP reported data on side effects. The pooled RR for side effects using the fixed effects model was 0.83 (95% CI 0.64�1.08), indicating no statistically significant difference. One systematic review of the harms of NSAIDs found that ibuprofen and diclofenac had the lowest gastrointestinal complication rate, mainly because of the low doses used in practice (pooled OR for adverse effects vs. placebo 1.30, 95% CI 0.91�1.80). COX2 inhibitors have been shown to have less gastrointestinal side effects in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis studies. However, increased cardiovascular risk (myocardial infarction and stroke) has been reported with long-term use.

Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions

Advice to Stay Active

Effectiveness of advice to stay active for acute LBP Stay active versus bed rest. The Cochrane review found four studies that compared advice to stay active as single treatment with bed rest. One high quality study showed that advice to stay active significantly improved functional status and reduced sick leave after 3 weeks compared with advice to rest in bed for 2 days. It also found a significant reduction of pain intensity in favour of the stay active group at intermediate follow-up (more than 3 weeks). The low quality studies showed conflicting results. The additional trial (278 people) found no significant differences in pain intensity and functional disability between advice to stay active and bed rest after 1 month. However, it found that advice to stay active significantly reduced sick leave compared with bed rest up to day 5 (52% with advice to stay active vs. 86% with bed rest; P<0.0001).

Stay active versus exercise. One trial found short-term improvement in functional status and reduction in sick leave in favour of advice to stay active. A significant reduction in sick leave in favour of the stay active group was also reported at long-term follow-up.

Effectiveness of advice to stay active for chronic LBP No trials identified.

Adverse effects No trials reported side effects.

Back Schools

The original �Swedish back school� was introduced by Zachrisson Forsell in 1969. It was intended to reduce the pain and prevent recurrences. The Swedish back school consisted of information on the anatomy of the back, biomechanics, optimal posture, ergonomics, and back exercises. Four small group sessions were scheduled during a 2-week period, with each session lasting 45 min. The content and length of back schools has changed and appears to vary widely today.

Effectiveness of back schools for acute LBP Back schools versus waiting list controls or �placebo� interventions. Only one trial compared back school with placebo (shortwaves at the lowest intensity) and showed better short-term recovery and return to work for the back school group. No other short- or long-term differences were found.

Back schools versus other interventions. Four studies (1,418 patients) showed conflicting evidence on the effectiveness of back schools compared to other treatments for acute and subacute LBP on pain, functional status, recovery, recurrences, and return to work (short-, intermediate-, and long-term follow-up).

Effectiveness of back schools for chronic LBP Back schools versus waiting list controls or �placebo� interventions. There is conflicting evidence (eight trials; 826 patients) on the effectiveness of back schools compared to waiting list controls or placebo interventions on pain, functional status, and return to work (short-, intermediate-, and long-term follow-up) for patients with chronic LBP.

Back schools versus other treatments. Six studies were identified comparing back schools with exercises, spinal or joint manipulation, myofascial therapy, and some kind of instructions or advice. There is moderate evidence (five trials; 1,095 patients) that a back school is more effective than other treatments for patients with chronic LBP for pain and functional status (short- and intermediate-term follow-up). There is moderate evidence (three trials; 822 patients) that there is no difference in long-term pain and functional status.

Adverse effects None of the trials reported any adverse effects.

Bed Rest

One rationale for bed rest is that many patients experience relief of symptoms in a horizontal position.

Effectiveness of bed rest for acute LBP Twelve trials were included in the Cochrane review. Some trials were on a mixed population of patients with acute and chronic LBP or on a population of patients with sciatica.

Bed rest versus advice to stay active. Three trials (481 patients) were included in this comparison. The results of two high quality trials showed small but consistent and significant differences in favour of staying active, at 3- to 4-week follow-up [pain: SMD 0.22 (95% CI 0.02�0.41); function: SMD 0.31 (95% CI 0.06�0.55)], and at 12-week follow-up [pain: SMD 0.25 (95% CI 0.05�0.45); function: SMD 0.25 (95% CI 0.02�0.48)]. Both studies also reported significant differences in sick leave in favour of staying active. There is strong evidence that advice to rest in bed is less effective than advice to stay active for reducing pain and improving functional status and speeding-up return to work.

Bed rest versus other interventions. Three trials were included. Two trials compared advice to rest in bed with exercises and found strong evidence that there was no difference in pain, functional status, or sick leave at short- and long-term follow-up. One study found no difference in improvement on a combined pain, disability, and physical examination score between bed rest and manipulation, drug therapy, physiotherapy, back school, or placebo.

Short bed rest versus longer bed rest. One trial in patients with sciatica reported no significant difference in pain intensity between 3 and 7 days of bed rest, measured 2 days after the end of treatment.

Effectiveness of bed rest for chronic LBP There were no trials identified.

Adverse effects No trials reported adverse effects.

Behavioural Treatment

The treatment of chronic LBP not only focuses on removing the underlying organic pathology, but also tries to reduce disability through the modification of environmental contingencies and cognitive processes. In general, three behavioural treatment approaches can be distinguished: operant, cognitive, and respondent. Each of these approaches focus on the modification of one of the three response systems that characterize emotional experiences: behaviour, cognition, and physiological reactivity.

Operant treatments include positive reinforcement of healthy behaviours and consequent withdrawal of attention towards pain behaviours, time-contingent instead of pain-contingent pain management, and spousal involvement. The operant treatment principles can be applied by all health care disciplines involved with the patient.

Cognitive treatment aims to identify and modify patients� cognitions regarding their pain and disability. Cognition (the meaning of pain, expectations regarding control over pain) can be modified directly by cognitive restructuring techniques (such as imagery and attention diversion), or indirectly by the modification of maladaptive thoughts, feelings, and beliefs.

Respondent treatment aims to modify the physiological response system directly, e.g. by reduction of muscular tension. Respondent treatment includes providing the patient with a model of the relationship between tension and pain, and teaching the patient to replace muscular tension by a tension-incompatible reaction, such as the relaxation response. Electromyographic (EMG) biofeedback, progressive relaxation, and applied relaxation are frequently used.

Behavioural techniques are often applied together as part of a comprehensive treatment approach. This so-called cognitive�behavioural treatment is based on a multidimensional model of pain that includes physical, affective, cognitive, and behavioural components. A large variety of behavioural treatment modalities are used for chronic LBP because there is no general consensus about the definition of operant and cognitive methods. Furthermore, behavioural treatment often consists of a combination of these modalities or is applied in combination with other therapies (such as medication or exercises).

Effectiveness of behavioural therapy for acute LBP One RCT (107 people) identified by the review found that cognitive�behavioural therapy reduced pain and perceived disability after 9�12 months compared with traditional care (analgesics plus back exercises until pain had subsided).

Effectiveness of behavioural therapy for chronic LBP Behavioural treatment versus waiting list controls. There is moderate evidence from two small trials (total of 39 people) that progressive relaxation has a large positive effect on pain (1.16; 95% CI 0.47�1.85) and behavioural outcomes (1.31; 95% CI 0.61�2.01) in the short-term. There is limited evidence that progressive relaxation has a positive effect on short-term back-specific and generic functional status.

There is moderate evidence from three small trials (total of 88 people) that there is no significant difference between EMG biofeedback and waiting list control on behavioural outcomes in the short-term. There is conflicting evidence (two trials; 60 people) on the effectiveness of EMG versus waiting list control on general functional status.

There is conflicting evidence from three small trials (total of 153 people) regarding the effect of operant therapy on short-term pain intensity, and moderate evidence that there is no difference [0.35 (95% CI -0.25 to 0.94)] between operant therapy and waiting list control for short-term behavioural outcomes. Five studies compared combined respondent and cognitive therapy with waiting list controls. There is strong evidence from four small trials (total of 134 people) that combined respondent and cognitive therapy has a medium sized, short-term positive effect on pain intensity. There is strong evidence that there are no differences [0.44 (95% CI -0.13 to 1.01)] on short-term behavioural outcomes.

Behavioural treatment versus other interventions. There is limited evidence (one trial; 39 people) that there are no significant differences between behavioural treatment and exercise on pain intensity, generic functional status and behavioural outcomes, either post-treatment, or at 6- or 12-month follow-up.

Adverse effects None reported in the trials.

Exercise Therapy

Exercise therapy is a management strategy that is widely used in LBP; it encompasses a heterogeneous group of interventions ranging from general physical fitness or aerobic exercise, to muscle strengthening, to various types of flexibility and stretching exercises.

Effectiveness of exercise therapy for acute LBP Exercise versus no treatment. The pooled analysis failed to show a difference in short-term pain relief between exercise therapy and no treatment, with an effect of -0.59 points/100 (95% CI -12.69 to 11.51).

Exercise versus other interventions. Of 11 trials involving 1,192 adults with acute LBP, 10 had non-exercise comparisons. These trials provide conflicting evidence. The pooled analysis showed that there was no difference at the earliest follow-up in pain relief when compared to other conservative treatments: 0.31 points (95% CI -0.10 to 0.72). Similarly, there was no significant positive effect of exercise on functional outcomes. Outcomes show similar trends at short-, intermediate-, and long-term follow-up.

Effectiveness of exercise therapy for subacute LBP Exercise versus other interventions. Six studies involving 881 subjects had non-exercise comparisons. Two trials found moderate evidence of reduced work absenteeism with a graded activity intervention compared to usual care. The evidence is conflicting regarding the effectiveness of other exercise therapy types in subacute LBP compared to other treatments.

Effectiveness of exercise therapy for chronic LBP Exercise versus other interventions. Thirty-three exercise groups in 25 trials on chronic LBP had non-exercise comparisons. These trials provide strong evidence that exercise therapy is at least as effective as other conservative interventions for chronic LBP. Two exercise groups in high quality studies and nine groups in low quality studies found exercise more effective than comparison treatments. These studies, mostly conducted in health care settings, commonly used exercise programs that were individually designed and delivered (as opposed to independent home exercises). The exercise programs commonly included strengthening or trunk stabilizing exercises. Conservative care in addition to exercise therapy was often included in these effective interventions, including behavioural and manual therapy, advice to stay active, and education. One low quality trial found a group-delivered aerobics and strengthening exercise program resulted in less improvement in pain and function outcomes than behavioural therapy. Of the remaining trials, 14 (2 high quality and 12 low quality) found no statistically significant or clinically important differences between exercise therapy and other conservative treatments; 4 of these trials were inadequately powered to detect clinically important differences on at least one outcome. Trials were rated low quality most commonly because of inadequate assessor blinding.

Meta-analysis of pain outcomes at the earliest follow-up included 23 exercise groups with an independent comparison and adequate data. Synthesis resulted in a pooled weighted mean improvement of 10.2 points (95% CI 1.31�19.09) for exercise therapy compared to no treatment, and 5.93 points (95% CI 2.21�9.65) compared to other conservative treatment [vs. all comparisons 7.29 points (95% CI 3.67�0.91)]. Smaller improvements were seen in functional outcomes with an observed mean positive effect of 3.15 points (95% CI -0.29 to 6.60) compared to no treatment, and 2.37 points (95% CI 0.74�4.0) versus other conservative treatment at the earliest follow-up [vs. all comparisons 2.53 points (95% CI 1.08�3.97)].

Adverse effects Most trials did not report any side effects. Two studies reported cardiovascular events that were considered not to be caused by the exercise therapy.

Lumbar Supports

Lumbar supports are provided as treatment to people suffering from LBP with the aim of making the impairment and disability vanish or decrease. Different desired functions have been suggested for lumbar supports: (1) to correct deformity, (2) to limit spinal motion, (3) to stabilize part of the spine, (4) to reduce mechanical uploading, and (5) miscellaneous effects: massage, heat, placebo. However, at the present time the putative mechanisms of action of a lumbar support remain a matter of debate.

Effectiveness of lumbar supports for acute LBP No trials were identified.

Effectiveness of lumbar supports for chronic LBP No RCT compared lumbar supports with placebo, no treatment, or other treatments for chronic LBP.

Effectiveness of lumbar supports for a mixed population of acute, subacute, and chronic LBP Four studies included a mix of patients with acute, subacute, and chronic LBP. One study did not give any information about the duration of the LBP complaints of the patients. There is moderate evidence that a lumbar support is not more effective in reducing pain than other types of treatment. Evidence on overall improvement and return to work was conflicting.

Adverse effects Potential adverse effects associated with prolonged lumbar support use include decreased strength of the trunk musculature, a false sense of security, heat, skin irritation, skin lesions, gastrointestinal disorders and muscle wasting, higher blood pressure and higher heart rates, and general discomfort.

Multidisciplinary Treatment Programmes

Multidisciplinary treatments for back pain evolved from pain clinics. Initially, multidisciplinary treatments focused on a traditional biomedical model and in the reduction of pain. Current multidisciplinary approaches to chronic pain are based on a multifactorial biopsychosicial model of interrelating physical, psychological, and social/occupational factors. The content of multidisciplinary programs varies widely and, at present, it is unclear what the optimal content is and who should be involved.

Effectiveness of multidisciplinary treatment for subacute LBP No trials identified.

Effectiveness of multidisciplinary treatment for subacute LBP Multidisciplinary treatment versus usual care. Two RCTs on subacute LBP were included. The study population in both studies consisted of workers on sick leave. In one study the patients in the intervention group returned to work sooner (10 weeks) compared with the control group (15 weeks) (P=0.03). The intervention group also had fewer sick leave during follow-up than the control group (mean difference=-7.5 days, 95% CI -15.06 to 0.06). There was no statistically significant difference in pain intensity between the intervention and control group, but subjective disability had decreased significantly more in the intervention group than in the control group (mean difference=-1.2, 95% CI -1.984 to -0.416). In the other study, the median duration of absence from regular work was 60 days for the group with a combination of occupational and clinical intervention, 67 days with the occupational intervention group, 131 days with the clinical intervention group, and 120.5 days with the usual care group (P=0.04). Return to work was 2.4 times faster in the group with both an occupational and clinical intervention (95% CI 1.19�4.89) than the usual care group, and 1.91 times faster in the two groups with occupational intervention than the two groups without occupational interventions (95% CI 1.18�3.1). There is moderate evidence that multidisciplinary treatment with a workplace visit and comprehensive occupational health care intervention is effective with regard to return to work, sick leave, and subjective disability for patients with subacute LBP.

Effectiveness of multidisciplinary treatment for chronic LBP Multidisciplinary treatment versus other interventions. Ten RCTs with a total of 1,964 subjects were included in the Cochrane review. Three additional papers reported on long-term outcomes of two of these trials. All ten trials excluded patients with significant radiculopathy or other indication for surgery. There is strong evidence that intensive multidisciplinary treatment with a functional restoration approach improves function when compared with inpatient or outpatient non-multidisciplinary treatments. There is moderate evidence that intensive multidisciplinary treatment with a functional restoration approach reduces pain when compared with outpatient non-multidisciplinary rehabilitation or usual care. There is contradictory evidence regarding vocational outcomes. Five trials evaluating less intensive multidisciplinary treatment programmes could not demonstrate beneficial effects on pain, function, or vocational outcomes when compared with non-multidisciplinary outpatient treatment or usual care. One additional RCT was found that showed no difference between multidisciplinary treatment and usual care on function and health related quality of life after 2 and 6 months.

The reviewed studies provide evidence that intensive (>100 h of therapy) MBPSR with a functional restoration approach produces greater improvements in pain and function for patients with disabling chronic LBP than non-multidisciplinary rehabilitation or usual care. Less intensive treatments did not seem effective.

Adverse effects No adverse effects were reported.

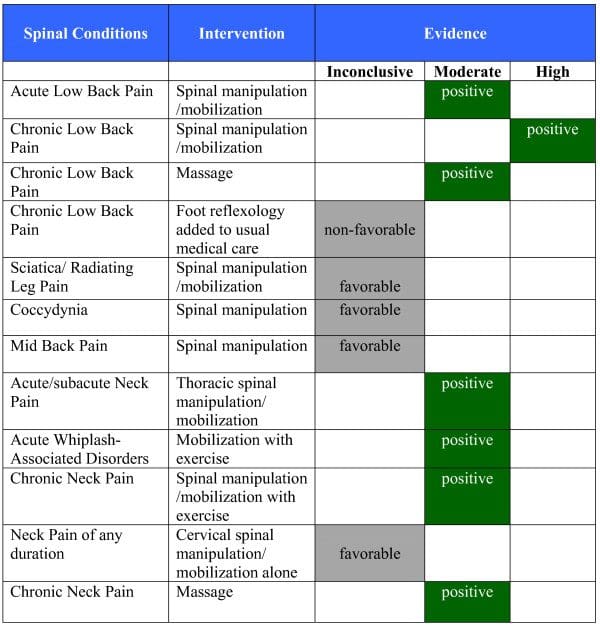

Spinal Manipulation

Spinal manipulation is defined as a form of manual therapy which involves movement of a joint past its usual end range of motion, but not past its anatomic range of motion. Spinal manipulation is usually considered as that of long lever, low velocity, non-specific type manipulation as opposed to short lever, high velocity, specific adjustment. Potential hypotheses for the working mechanism of spinal manipulation are: (1) release for the entrapped synovial folds, (2) relaxation of hypertonic muscle, (3) disruption of articular or periarticular adhesion, (4) unbuckling of motion segments that have undergone disproportionate displacement, (5) reduction of disc bulge, (6) repositioning of miniscule structures within the articular surface, (7) mechanical stimulation of nociceptive joint fibres, (8) change in neurophysiological function, and (9) reduction of muscle spasm.

Effectiveness of spinal manipulation for acute LBP Spinal manipulation versus sham. Two trials were identified. Patients receiving treatment that included spinal manipulation had statistically significant and clinically important short-term improvements in pain (10-mm difference; 95% CI 2�17 mm) compared with sham therapy. However, the improvement in function was considered clinically relevant but not statistically significant (2.8-mm difference on the Roland Morris scale; 95% CI -0.1 to 5.6).

Spinal manipulation versus other therapies. Twelve trials were identified. Spinal manipulation resulted in statistically significant more short-term pain relief compared with other therapies judged to be ineffective or possibly even harmful (4-mm difference; 95% CI 1�8 mm). However, the clinical significance of this finding is questionable. The point estimate of improvement in short-term function for treatment with spinal manipulation compared with the ineffective therapies was considered clinically significant but was not statistically significant (2.1-point difference on the Roland Morris scale; 95% CI -0.2 to 4.4). There were no differences in effectiveness between patients treated with spinal manipulation and those treated with any of the conventionally advocated therapies.

Effectiveness of spinal manipulation for chronic LBP Spinal manipulation versus sham. Three trials were identified. Spinal manipulation was statistically significantly more effective compared with sham manipulation on short-term pain relief (10 mm; 95% CI 3�17 mm) and long-term pain relief (19 mm; 95% CI 3�35 mm). Spinal manipulation was also statistically significantly more effective on short-term improvement of function (3.3 points on the Roland and Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ); 95% CI 0.6�6.0).

Spinal manipulation versus other therapies. Eight trials were identified. Spinal manipulation was statistically significantly more effective compared with the group of therapies judged to be ineffective or perhaps harmful on short-term pain relief (4 mm; 95% CI 0�8), and short-term improvement in function (2.6 points on the RMDQ; 95% CI 0.5�4.8). There were no differences in short- and long-term effectiveness compared with other conventionally advocated therapies such as general practice care, physical or exercise therapy, and back school.

Adverse effects In the RCTs identified by the review that used a trained therapist to select people and perform spinal manipulation, the risk of serious complications was low. An estimate of the risk of spinal manipulation causing a clinically worsened disk herniation or cauda equina syndrome in a patient presenting with lumbar disk herniation is calculated from published data to be less than 1 in 3.7 million.

Traction

Lumbar traction uses a harness (with velcro strapping) that is put around the lower rib cage and around the iliacal crest. Duration and level of force exerted through this harness can be varied in a continuous or intermittent mode. Only in motorized and bed rest traction can the force be standardized. With other techniques total body weight and the strength of the patient or therapist determine the forces exerted. In the application of traction force, consideration must be given to counterforces such as lumbar muscle tension, lumbar skin stretch and abdominal pressure, which depend on the patient�s physical constitution. If the patient is lying on the traction table, the friction of the body on the table provides the main counterforce during traction. The exact mechanism through which traction might be effective is unclear. It has been suggested that spinal elongation, through decreasing lordosis and increasing intervertebral space, inhibits nociceptive impulses, improves mobility, decreases mechanical stress, reduces muscle spasm or spinal nerve root compression (due to osteophytes), releases luxation of a disc or capsule from the zygo-apophysial joint, and releases adhesions around the zygo-apophysial joint and the annulus fibrosus. So far, the proposed mechanisms have not been supported by sufficient empirical information.

Thirteen of the studies identified in the Cochrane review included a homogeneous population of LBP patients with radiating symptoms. The remaining studies included a mix of patients with and without radiation. There were no studies exclusively involving patients who had no radiating symptoms.

Five studies included solely or primarily patients with chronic LBP of more than 12 weeks; in one study patients were all in the subacute range (4�12 weeks). In 11 studies the duration of LBP was a mixture of acute, subacute, and chronic. In four studies duration was not specified.

Effectiveness of traction for acute LBP No RCTs included primarily people with acute LBP. One study was identified that included patients with subacute LBP, but this population consisted of a mix of patients with and without radiation.

Effectiveness of traction for chronic LBP One trial found that continuous traction is not more effective on pain, function, overall improvement, or work absenteeism than placebo. One RCT (42 people) found no difference in effectiveness between standard physical therapy including continuous traction and the same program without traction. One RCT (152 people) found no significant difference between lumbar traction plus massage and interferential treatment in pain relief, or improvement of disability 3 weeks and 4 months after the end of treatment. This RCT did not exclude people with sciatica, but no further details of the proportion of people with sciatica were reported. One RCT (44 people) found that autotraction is more effective than mechanical traction on global improvement, but not on pain and function, in chronic LBP patients with or without radiating symptoms. However, this trial had several methodological problems that may be associated with biased results.

Adverse effects Little is known about the adverse effects of traction. Only a few case reports are available, which suggest that there is some danger for nerve impingement in heavy traction, i.e. lumbar traction forces exceeding 50% of the total body weight. Other risks described for lumbar traction are respiratory constraints due to the traction harness or increased blood pressure during inverted positional traction. Other potential adverse effects of traction include debilitation, loss of muscle tone, bone demineralization, and thrombophlebitis.

Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) is a therapeutic non-invasive modality mainly used for pain relief by electrically stimulating peripheral nerves via skin surface electrodes. Several types of TENS applications, differing in intensity and electrical characteristics, are used in clinical practice: (1) high frequency, (2) low frequency, (3) burst frequency, and (4) hyperstimulation.

Effectiveness of TENS for acute LBP: No trials were identified.

Effectiveness of TENS for chronic LBP The Cochrane review included two RCTs of TENS for chronic LBP. The results of one small trial (N=30) showed a significant decrease in subjective pain intensity with active TENS treatment compared to placebo over the course of the 60-min treatment session. The pain reduction seen at the end of stimulation was maintained for the entire 60-min post-treatment time interval assessed (data not shown). Longer term follow-up was not conducted in this study. The second trial (N=145) demonstrated no significant difference between active TENS and placebo for any of the outcomes measured, including pain, functional status, range of motion, and use of medical services.

Adverse effects In a third of the participants in one trial, minor skin irritation occurred at the site of electrode placement. These adverse effects were observed equally in the active TENS and placebo groups. One participant randomized to placebo TENS developed severe dermatitis 4 days after beginning therapy and was required to withdraw (Tables 1, ?2).

Table 1: Effectiveness of conservative interventions for acute non-specific low back pain.

Table 2: Effectiveness of conservative interventions for chronic non-specific low back pain.

Discussion

The best available evidence for conservative treatments for non-specific LBP summarized in this paper shows that some interventions are effective. Traditional NSAIDs, muscle relaxants, and advice to stay active are effective for short-term pain relief in acute LBP. Advice to stay active is also effective for long-term improvement of function in acute LBP. In chronic LBP, various interventions are effective for short-term pain relief, i.e. antidepressants, COX2 inhibitors, back schools, progressive relaxation, cognitive�respondent treatment, exercise therapy, and intensive multidisciplinary treatment. Several treatments are also effective for short-term improvement of function in chronic LBP, namely COX2 inhibitors, back schools, progressive relaxation, exercise therapy, and multidisciplinary treatment. There is no evidence that any of these interventions provides long-term effects on pain and function. Also, many trials showed methodological weaknesses, effects are compared to placebo, no treatment or waiting list controls, and effect sizes are small. Future trials should meet current quality standards and have adequate sample size. However, in summary, there is evidence that some interventions are effective while evidence for many other interventions is lacking or there is evidence that they are not effective.

During the last decade, various clinical guidelines on the management of acute LBP in primary care have been published that have used this evidence. At present, guidelines exist in at least 12 different countries: Australia, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Israel, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Since the available evidence is international, one would expect that each country�s guidelines would give more or less similar recommendations regarding diagnosis and treatment. Comparison of clinical guidelines for the management of LBP in primary care from 11 different countries showed that the content of the guidelines regarding therapeutic interventions is quite similar. However, there were also some discrepancies in recommendations across guidelines. Differences in recommendations between guidelines may be due to incompleteness of the evidence, different levels of evidence, magnitude of effects, side effects and costs, differences in health care systems (organization/financial), or differences in membership of guidelines committees. More recent guidelines may have included more recently published trials and, therefore, may end up with slightly different recommendations. Also, guidelines may have been based on systematic reviews that included trials in different languages; the majority of existing reviews have considered only studies published in a few languages, and several, only those published in English. Recommendations in guidelines are not only based on scientific evidence, but also on consensus. Guideline committees may consider various arguments differently, such as the magnitude of the effects, potential side effects, cost-effectiveness, and current routine practice and available resources in their country. Especially as we know that effects in the field of LBP, if any, are usually small and short-term effects only, interpretation of effects may vary among guideline committees. Also, guideline committees may differently weigh other aspects such as side effects and costs. The constitution of the guideline committees and the professional bodies they represent may introduce bias�either for or against a particular treatment. This does not necessarily mean that one guideline is better than the other or that one is right and the other is wrong. It merely shows that when translating the evidence into clinically relevant recommendations more aspects play a role, and that these aspects may vary locally or nationally.

Recently European guidelines for the management of LBP were developed to increase consistency in the management of non-specific LBP across countries in Europe. The European Commission has approved and funded this project called �COST B13�. The main objectives of this COST action were developing European guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of non-specific LBP, ensuring an evidence-based approach through the use of systematic reviews and existing clinical guidelines, enabling a multidisciplinary approach, and stimulating collaboration between primary health care providers and promoting consistency across providers and countries in Europe. Representatives from 13 countries participated in this project that was conducted between 1999 and 2004. The experts represented all relevant health professions in the field of LBP: anatomy, anaesthesiology, chiropractic, epidemiology, ergonomy, general practice, occupational care, orthopaedic surgery, pathology, physiology, physiotherapy, psychology, public health care, rehabilitation, and rheumatology. Within this COST B13 project four European guidelines were developed on: (1) acute LBP, (2) chronic LBP, (3) prevention of LBP, and (4) pelvic girdle pain. The guidelines will soon be published as a supplement to the European Spine Journal.

Contributor Information

Maurits W. van Tulder, Bart Koes, Antti Malmivaara: Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

In conclusion,�the clinical and experimental evidence above for non-invasive treatment modalities on back pain demonstrated that several of the treatments are safe and effective. While the results of a variety of the methods used to improve back pain symptoms were proven to be efficient, many other treatment modalities requires additional evidence and others were reported to not be effective towards improving symptoms of back pain.�The main objective of the research study was to determine the safest and most effective guideline for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of non-specific back pain.�Information referenced from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic as well as to spinal injuries and conditions. To discuss the subject matter, please feel free to ask Dr. Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

Curated by Dr. Alex Jimenez

Additional Topics: Sciatica

Sciatica is referred to as a collection of symptoms rather than a single type of injury or condition. The symptoms are characterized as radiating pain, numbness and tingling sensations from the sciatic nerve in the lower back, down the buttocks and thighs and through one or both legs and into the feet. Sciatica is commonly the result of irritation, inflammation or compression of the largest nerve in the human body, generally due to a herniated disc or bone spur.

IMPORTANT TOPIC: EXTRA EXTRA: Treating Sciatica Pain

Edward Stiles

Edward Stiles

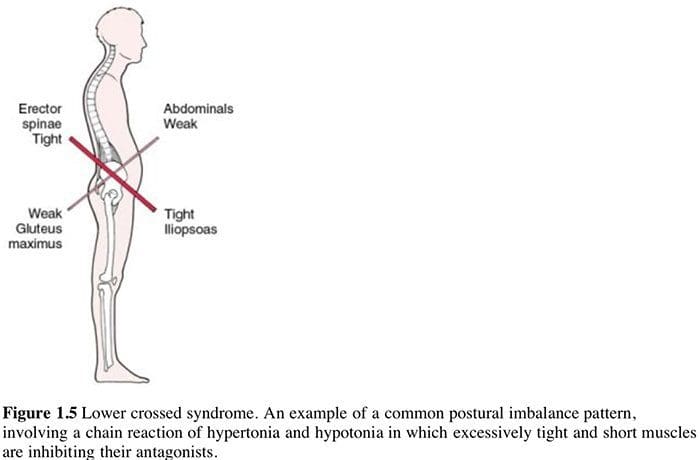

Liebenson (1996) discusses both the benefits of, and the mechanisms involved in, use of muscle energy techniques (which he terms �manual resistance techniques�, or MRT):

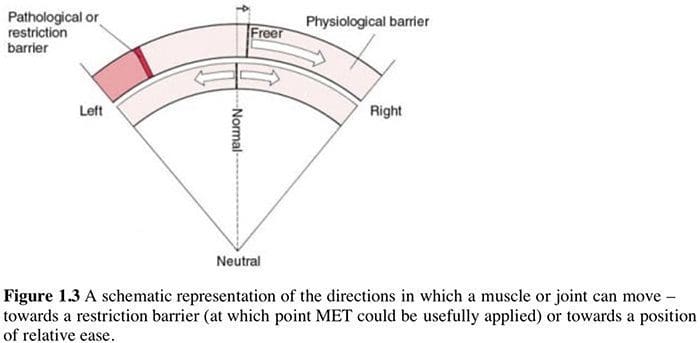

Liebenson (1996) discusses both the benefits of, and the mechanisms involved in, use of muscle energy techniques (which he terms �manual resistance techniques�, or MRT): Using agonist or antagonist? (Box 1.4)

Using agonist or antagonist? (Box 1.4)

What Is Happening?

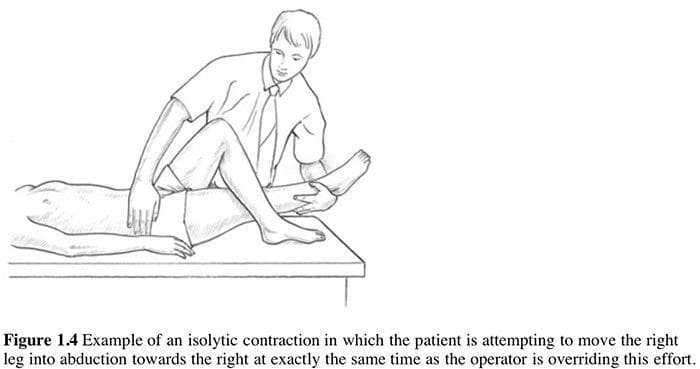

What Is Happening? This stretches the muscles which are contracting (TFL shown in example) thereby inducing a degree of controlled microtrauma, with the aim of increasing the elastic potential of shortened or fibrosed tissues.

This stretches the muscles which are contracting (TFL shown in example) thereby inducing a degree of controlled microtrauma, with the aim of increasing the elastic potential of shortened or fibrosed tissues. Muscle energy techniques are designed to assist in this endeavor and, as discussed above, also provides an excellent method for assisting in the toning of weak musculature, should this still be required, after the

Muscle energy techniques are designed to assist in this endeavor and, as discussed above, also provides an excellent method for assisting in the toning of weak musculature, should this still be required, after the  The relevance of this to soft tissue techniques is explained as follows:

The relevance of this to soft tissue techniques is explained as follows:

El Paso, TX, INJURY MEDICAL & CHIROPRACTIC CLINIC announces its newest east side location at 11860 Vista Del Sol, Suite 128 will officially open. The clinic is located in The Mission Business Center near Walgreens.

El Paso, TX, INJURY MEDICAL & CHIROPRACTIC CLINIC announces its newest east side location at 11860 Vista Del Sol, Suite 128 will officially open. The clinic is located in The Mission Business Center near Walgreens. Based in El Paso, TX Injury Medical & Chiropractic Clinic is reinventing chiropractic by making quality care convenient and affordable for patients seeking pain relief and ongoing wellness. Extended hours and three convenient locations make care more accessible. Injury Medical & Chiropractic Clinic is an emerging company and key leader in the chiropractic profession. For more information, visit

Based in El Paso, TX Injury Medical & Chiropractic Clinic is reinventing chiropractic by making quality care convenient and affordable for patients seeking pain relief and ongoing wellness. Extended hours and three convenient locations make care more accessible. Injury Medical & Chiropractic Clinic is an emerging company and key leader in the chiropractic profession. For more information, visit