1.�Phillips, K. & Clauw, D. J. (2011). Central pain mechanisms in chronic pain states � maybe it is all in their head.�Best Practice Research in Clinical Rheumatology, 25, 141-154.

2.�Yunus, M. B. (2007). The role of central sensitization in symptoms beyond muscle pain, and the evaluation of a patient with widespread pain.�Best Practice Research in Clinical Rheumatology, 21, 481-497.

3.�Curatolo, M., Arendt-Nielsen, L., & Petersen-Felix, S. (2006). Central hypersensitivity in chronic pain: Mechanisms and clinical implications.�Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, 17, 287-302.

4.�Wieseler-Frank, J., Maier, S. F., & Watkins, L. R. (2005). Immune-to-brain communication dynamically modulates pain: Physiological and pathological consequences.�Brain, Behavior, & Immunity, 19, 104-111.

5.�Meeus M., & Nijs, J. (2007). Central sensitization: A biopsychosocial explanation for chronic widespread pain in patients with fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome.�Clinical Journal of Rheumatology, 26, 465-473.

6. Melzack, R., Coderre, T. J., Kat, J., & Vaccarino, A. L. (2001). Central neuroplasticity and pathological pain.�Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 933, 157-174.

7.�Flor, H., Braun, C., Elbert, T., & Birbaumer, N. (1997). Extensive reorganization of primary somatosensory cortex in chronic back pain patients.�Neuroscience Letters, 224, 5-8.

8. O�Neill, S., Manniche, C., Graven-Nielsen, T., Arendt-Nielsen, L. (2007). Generalized deep-tissue hyperalgesia in patients with chronic low-back pain.�European Journal of Pain, 11, 415-420.

9.�Chua, N. H., Van Suijlekom, H. A., Vissers, K. C., Arendt-Nielsen, L., & Wilder-Smith, O. H. (2011). Differences in sensory processing between chronic cervical zygapophysial joint pain patients with and without cervicogenic headache.�Cephalalgia, 31, 953-963.

10.�Banic, B, Petersen-Felix, S., Andersen O. K., Radanov, B. P., Villiger, P. M., Arendt-Nielsen, L., & Curatolo, M. (2004). Evidence for spinal cord hypersensitivity in chronic pain after whiplash injury and fibromyalgia.�Pain, 107, 7-15.

11.�Bendtsen, L. (2000). Central sensitization in tension-type headaches � possible pathophysiological mechanisms.�Cephalalgia, 20, 486-508.

12. Coppola, G., DiLorenzo, C., Schoenen, J. & Peirelli, F. (2013). Habituation and sensitization in primary headaches. Journal of Headache and Pain, 14, 65.

13.�Stankewitz, A., & May, A. (2009). The phenomenon of changes in cortical excitability in migraine is not migraine-specific � A unifying thesis.�Pain, 145, 14-17.

14.�Meeus M., Vervisch, S., De Clerck, L. S., Moorkens, G., Hans, G., & Nijs, J. (2012). Central sensitization in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic literature review.�Seminars in Arthritis & Rheumatism, 41, 556-567.

15.�Arendt-Nielsen, L., Nie, H., Laursen M. B., Laursen, B. S., Madeleine P., Simonson O. H., & Graven-Nielsen, T. (2010). Sensitization in patients with painful knee osteoarthritis.�Pain, 149, 573-581.

16.�Bajaj, P., Bajaj, P., Madsen, H., & Arendt-Nielsen, L. (2003). Endometriosis is associated with central sensitization: A psychophysical controlled study.�The Journal of Pain, 4, 372-380.

17.�McLean, S., Clauw, D. J., Abelson, J. L., & Liberzon, I. (2005). The development of persistent pain and psychological morbidity after motor vehicle collision: Integrating the potential role of stress response systems into a biopsychosocial model.�Psychosomatic Medicine, 67, 783-790.

18.�Fernandez-Lao, Cantarero-Villanueva, I., Fernandez-de-Las-Penas, C, Del-Moral-Avila, R., Arendt-Nielsen, L., Arroyo-Morales, M. (2010). Myofascial trigger points in neck and shoulder muscles and widespread pressure pain hypersensitivity in patients with post-mastectomy pain: Evidence of peripheral and central sensitization.�Clinical Journal of Pain, 26, 798-806.

19.�Staud, R. (2006). Biology and therapy of fibromyalgia: Pain in fibromyalgia syndrome.�Arthritis Research and Therapy, 8, 208.

20. Verne, V. N., & Price, D. D. (2002). Irritable bowel syndrome as a common precipitant of central sensitization.�Current Rheumatology Reports, 4, 322-328.

21.�Meeus M., & Nijs, J. (2007). Central sensitization: A biopsychosocial explanation for chronic widespread pain in patients with fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome.�Clinical Journal of Rheumatology, 26, 465-473.

22.�Schwartzman, R. J., Grothusen, R. J., Kiefer, T. R., & Rohr, P. (2001). Neuropathic central pain: Epidemiology, etiology, and treatment options.�Archives of Neurology, 58, 1547-1550.

23.�Alexander, J., DeVries, A., Kigerl, K., Dahlman, J., & Popovich, P. (2009). Stress exacerbates neuropathic pain via glucocorticoid and NMDA receptor activation.�Brain, Behavior and Immunity, 23, 851-860.

24. Imbe, H., Iwai-Liao, Y., & Senba, E. (2006). Stress-induced hyperalgesia: Animal models and putative mechanisms.�Frontiers in Bioscience, 11, 2179-2192.

25. Kuehl, L. �K., Michaux, G. �P., Richter, S., Schachinger, H., & Anton F. (2010). Increased basal mechanical sensitivity but decreased perceptual wind-up in a human model of relative hypocortisolism.�Pain, 194, 539-546.

26. Rivat, C., Becker, C., Blugeot, A., Zeau, B., Mauborgne, A., Pohl, M., & Benoliel, J. (2010). Chronic stress induces transient spinal neuroinflammation, triggering sensory hypersensitivity and long-lasting anxiety-induced hyperalgesia.�Pain, 150, 358-368.

27.�Slade, G. D., Diatchenko, L., Bhalang, K., Sigurdsson, A., Fillingim, R. B., Belfer, I., Max, M. B., Goldman, D., & Maixner, W. (2007). Influence of psychological factors on risk of temporomandibular disorders.�Journal of Dental Research, 86, 1120-1125.

28.�Hirsh, A. T., George, S. Z., Bialosky, J. E., & Robinson, M. E. (2008). Fear of pain, pain catastrophizing, and acute pain perception: Relative prediction and timing of assessment.�Journal of Pain, 9, 806-812.

29. Sullivan, M. J. Thorn, B., Rodgers, W., & Ward, L. C. (2004). Path model of psychological antecedents to pain experience: Experimental and clinical findings.�Clinical Journal of Pain, 20, 164-173.

30.�Nahit, E. S., Hunt, I. M., Lunt, M., Dunn, G., Silman, A. J., & Macfarlane, G. J. (2003). Effects of psychosocial and individual psychological factors on the onset of musculoskeletal pain: Common and site-specific effects.�Annals of Rheumatic Disease, 62, 755-760.

31. Talbot, N. L., Chapman, B., Conwell, Y., McCollumn, K., Franus, N., Cotescu, S., & Duberstein, P. R. (2009). Childhood sexual abuse is associated with physical illness burden and functioning in psychiatric patients 50 years of age or older.�Psychosomatic Medicine, 71, 417-422.

32. McLean, S. A., Clauw, D. J., Abelson, J. L., & Liberzon, I. (2005). The development of persistent pain and psychological morbidity after motor vehicle collision: Integrating the potential role of stress response systems into a biopsychosocial model.�Psychosomatic Medicine, 67, 783-790.

33. Hauser, W., Galek, A., Erbsloh-Moller, B., Kollner, V., Kuhn-Becker, H., Langhorst, J… & Glaesmer, H. (2013). Posttraumatic stress disorder in fibromyalgia syndrome: Prevalence, temporal relationship between posttraumatic stress and fibromyalgia symptoms and impact on clinical outcome.�Pain, 154, 1216-1223.

34.�Diatchenko, L., Nackley, A. G., Slade, G. D., Fillingim, R. B., & Maixner, W. (2006). Idiopathic pain disorders � Pathways of vulnerability.�Pain, 123, 226-230.

35.�Azevedo, E., Manzano, G. M., Silva, A., Martins, R., Andersen, M. L., & Tufik, S. (2011). The effects of total and REM sleep deprivation on laser-invoked potential threshold and pain perception.�Pain, 152, 2052-2058.

36. Chiu, Y. H., Silman, A. J., Macfarlane, G. J., Ray, D., Gupta, A., Dickens, C., Morris, R., & McBeth, J. (2005). Poor sleep and depression are independently associated with a reduced pain threshold: Results of a population based study.�Pain, 115, 316-321.

37.�Holzl, R., Kleinbohl, D. & Huse, E. (2005). Implicit operant learning of pain sensitization.�Pain, 115, 12-20.

38. Baumbauer, K. M., Young, E. E., & Joynes, R. L. (2009). Pain and learning in spinal system: Contradictory outcomes from common origins.�Brain Research Reviews, 61, 124-143.

39. Becker, S., Kleinbohl, D., Baus, D., & Holzl, R. (2011). Operant learning of perceptual sensitization and habituation is impaired in fibromyalgia patients with and without irritable bowel syndrome.�Pain, 152, 1408-1417.

40.�Hauser, W., Wolfe, F., Tolle, T., Uceyler, N. & Sommer, C. (2012). The role of antidepressants in the management of fibromyalgia: A systematic review and meta-analysis.�CNS Drugs, 26, 297-307.

41.�Hauser, W., Bernardy, K., Uceyler, N., & Sommer, C. (2009). Treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome with gabapentin and pregabalin � A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.�Pain, 145, 169-181.

42. Straube, S., Derry, S., Moore, R. A., & McQuay, H. J. (2010). Pregabalin in fibromyalgia: Meta-analysis of efficacy and safety from company clinical trial reports.�Rheumatology, 49, 706-715.

43. Tzellos, T. G., Toulis, K. A., Goulis, D. G., Papazisis, G., Zampellis, Z. A., Vakfari, A., & Kouvelas, D. (2010). Gabapentin and pregabalin in the treatment of fibromyalgia: A systematic review and meta-analysis.�Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 35, 639-656.

44.�Thieme, K. Flor, H., & Turk, D. C. (2006). Psychological pain treatment in fibromyalgia syndrome: Efficacy of operant behavioral and cognitive behavioral treatments.�Arthritis Research & Therapy, 8, R121.

45. Lackner, J. M., Mesmer, C., Morley, S., Dowzer, C., & Hamilton, S. (2004). Psychological treatments for irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis.�Journal of Clinical and Consulting Psychology, 72, 1100-1113.

46. Salomons, T. V., Moayedi, M. Erpelding, N., & Davis, K. D. (2014). A brief cognitive-behavioral intervention for pain reduces secondary hyperalgesia. Pain, 155, 1446-1452. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014,02.012

47.�Erickson, K. I., Voss., M. W., Prakesh, R. S., et al. (2011). Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory.�Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, 3017-3022.

48. Hilman, C. H., Erickson, K. I., & Kramer, A. F. (2008). Be smart, exercise your heart: Exercise effects on brain and cognition.�Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9, 58-65.

49.�Busch, A. J., Barber, K. A., Overend, T. J., Peloso, P. M., & Schachter, C. L. (Updated August 17, 2007). Exercise for treating fibromyalgia. In Cochrane Database Reviews, 2007, (4). Retrieved May 16, 2011, from The Cochrane Library, Wiley Interscience.

50.�Fordyce, W. E., Fowler, R. S., Lehmann, J. F., Delateur, B. J., Sand, P. L., & Trieschmann, R. B. (1973). Operant conditioning in the treatment of chronic pain.�Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 54, 399-408.

51. Gatzounis, R., Schrooten, M. G., Crombez, G., & Vlaeyen, J. W. (2012). Operant learning theory in pain and chronic pain rehabilitation.�Current Pain and Headache Reports, 16, 117-126.

52.�Hauser, W., Bernardy, K., Arnold, B., Offenbacher, M., & Schiltenwolf, M. (2009). Efficacy of multicomponent treatment in fibromyalgia syndrome: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials.�Arthritis & Rheumatism, 61, 216-224.

53. Flor, H., Fydrich, T. & Turk, D. C. (1992). Efficacy of multidisciplinary pain treatment centers: A meta-analytic review.�Pain, 49, 221-230.

54. Gatchel, R., J., & Okifuji, A. (2006). Evidence-based scientific data documenting the treatment and cost-effectiveness of comprehensive pain programs for chronic non-malignant pain.�Journal of Pain, 7, 779-793.

55. Turk, D. C. (2002). Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of treatments for patients with chronic pain.�The Clinical Journal of Pain, 18, 355-365.

We are blessed to present to you�El Paso�s Premier Wellness & Injury Care Clinic.

We are blessed to present to you�El Paso�s Premier Wellness & Injury Care Clinic.

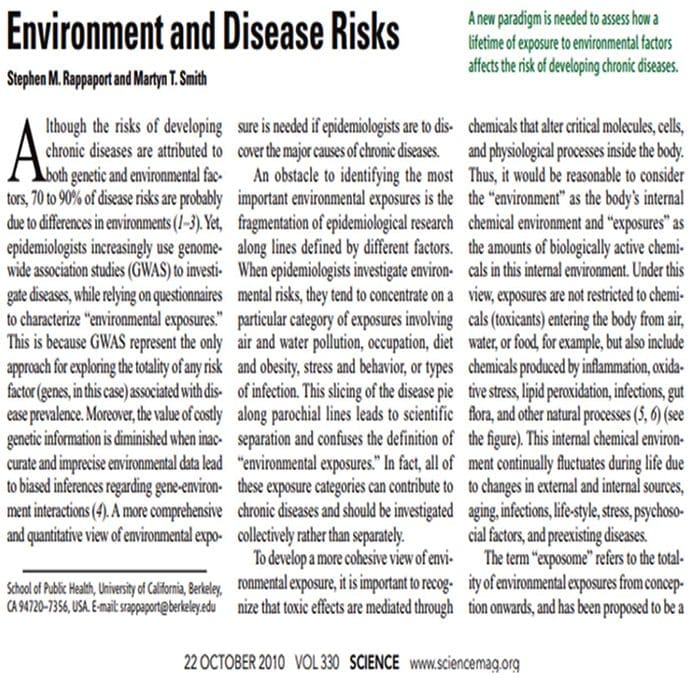

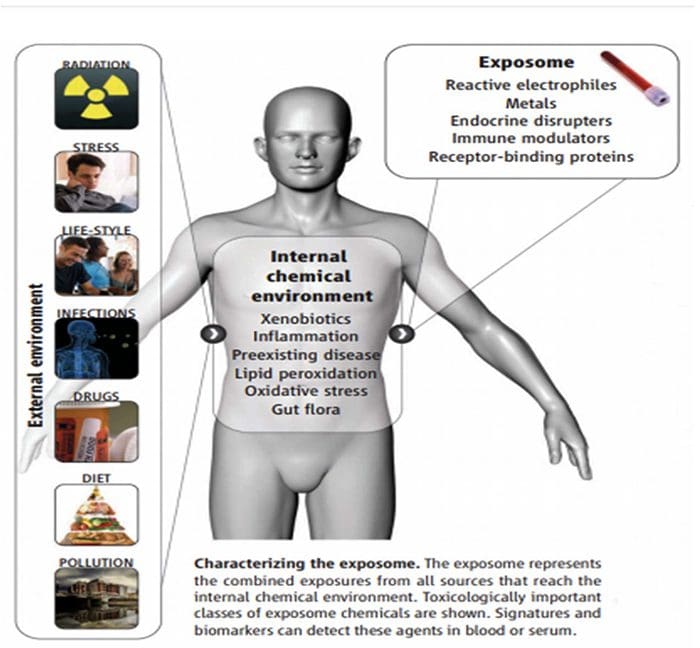

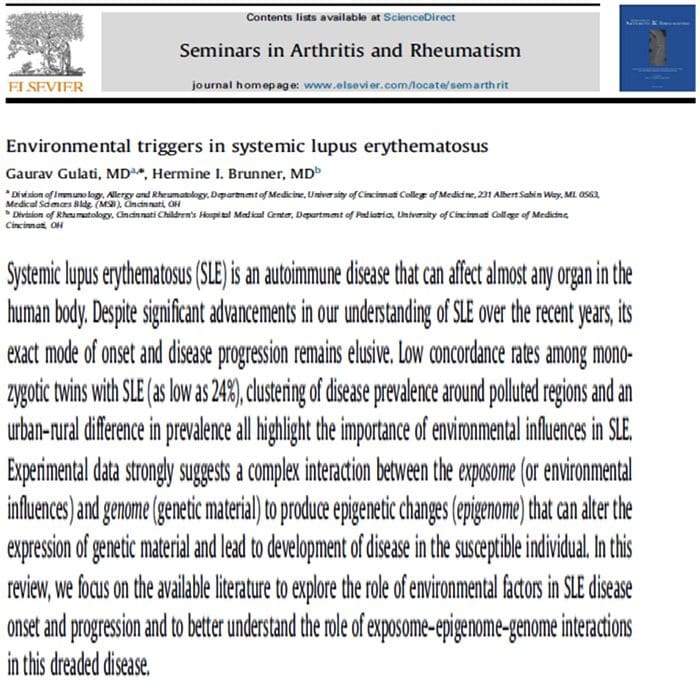

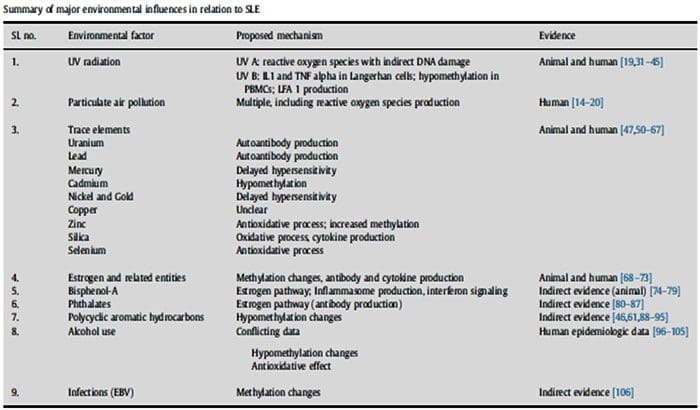

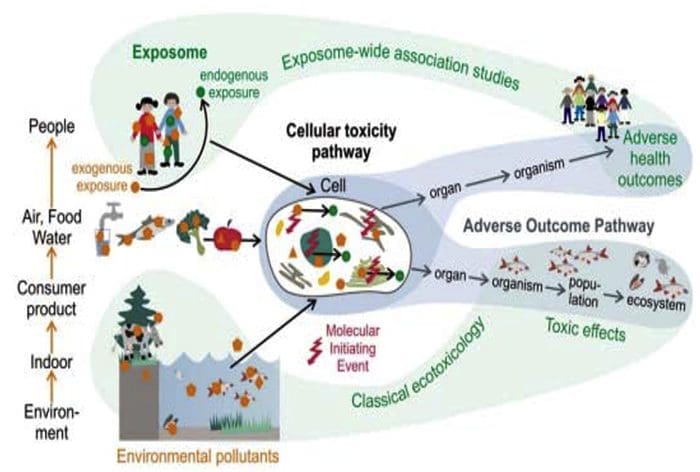

The Ecology Of The Exposome

The Ecology Of The Exposome Exposome & The Alteration Of �Self�

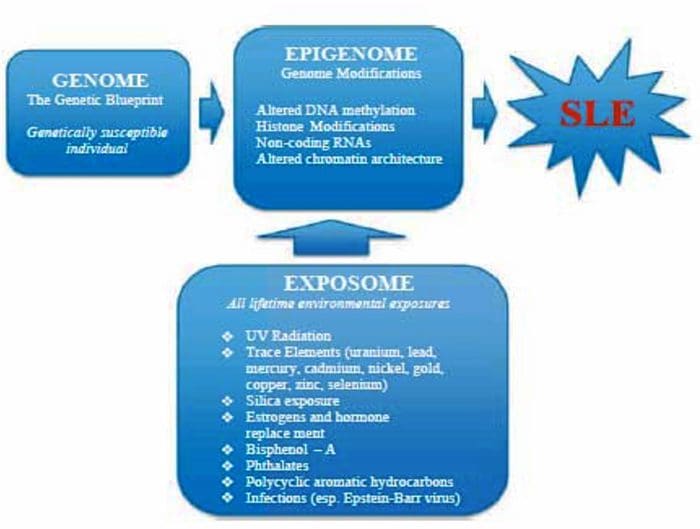

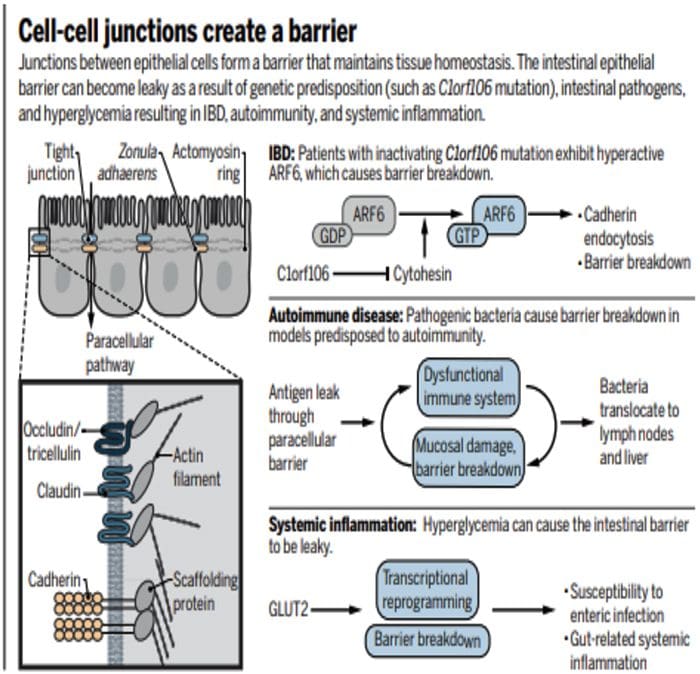

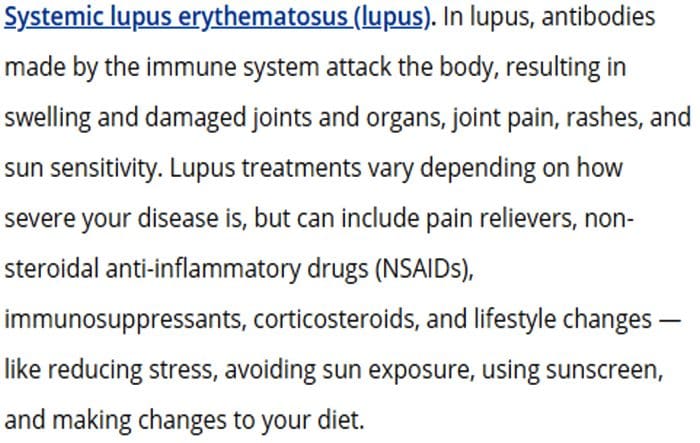

Exposome & The Alteration Of �Self� The Exposome Connections To Autoimmune Diseases Converting Self Into Non?Self

The Exposome Connections To Autoimmune Diseases Converting Self Into Non?Self

Multi?Organ Network Biology

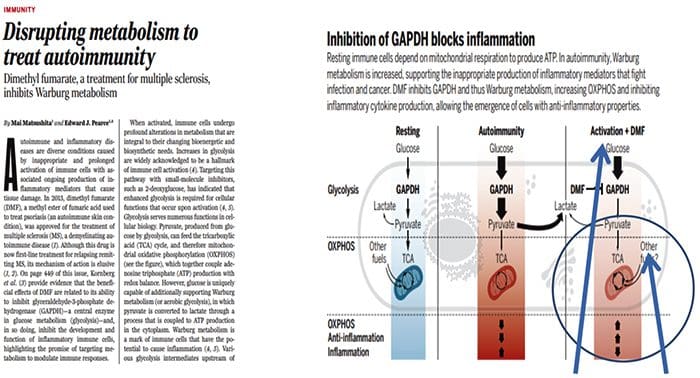

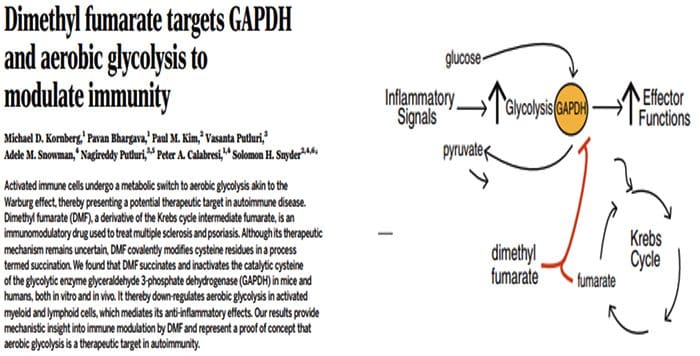

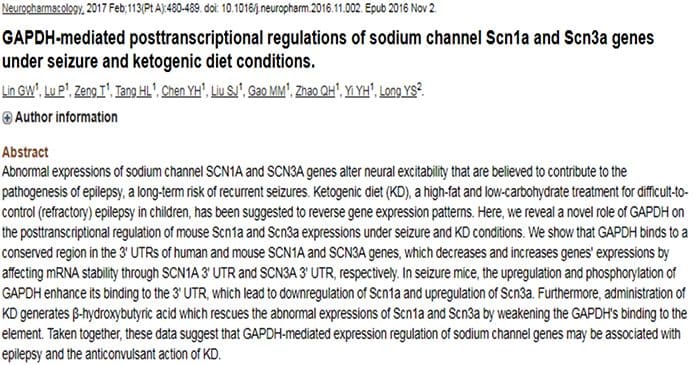

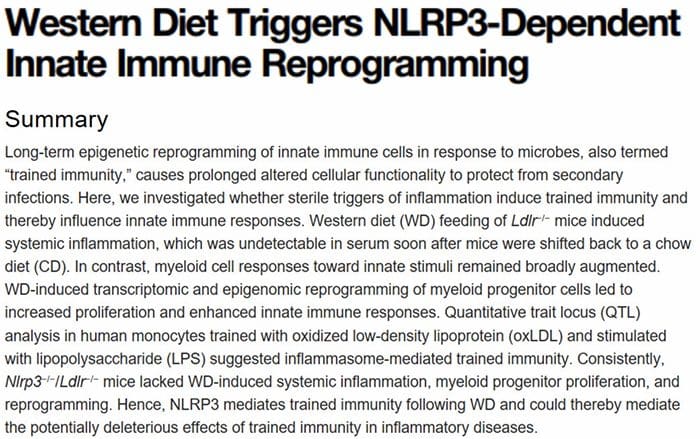

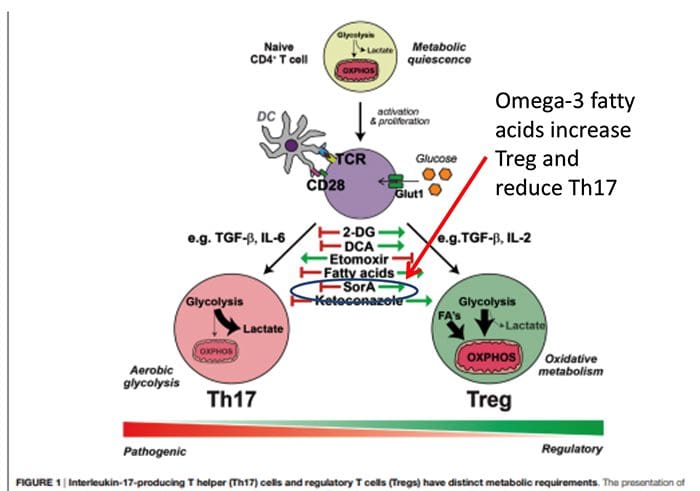

Multi?Organ Network Biology In Autoimmunity, Warburg Metabolism Is Increased Through Increased Activity Of GAPDH

In Autoimmunity, Warburg Metabolism Is Increased Through Increased Activity Of GAPDH

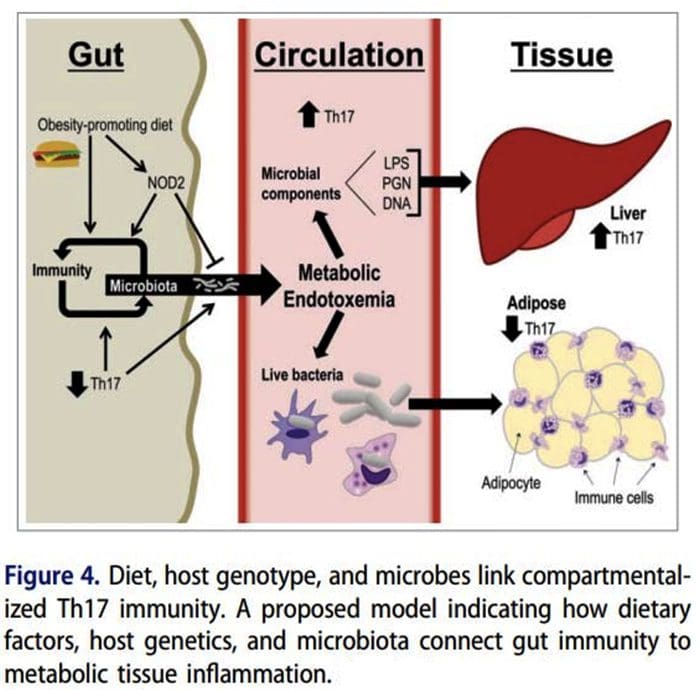

Origin Of IL?17 Producing Th17 Cells

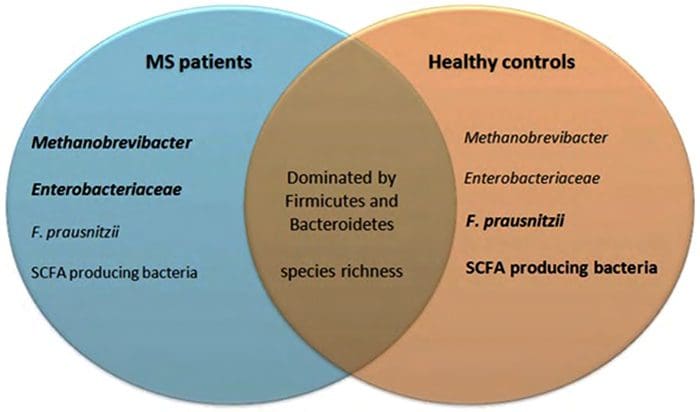

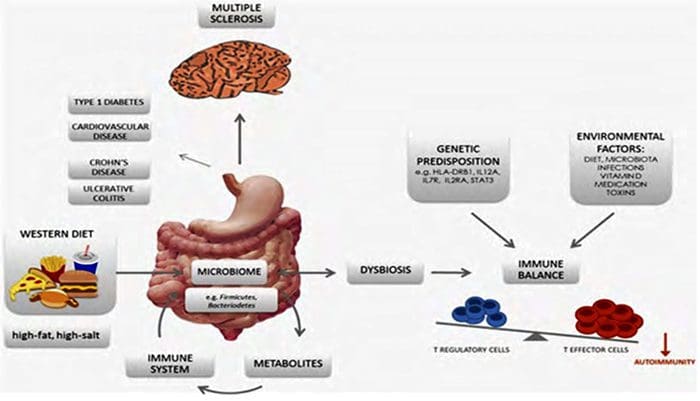

Origin Of IL?17 Producing Th17 Cells What Is The Relationship Of The Gut Microbiome To Autoimmune Disease?

What Is The Relationship Of The Gut Microbiome To Autoimmune Disease?

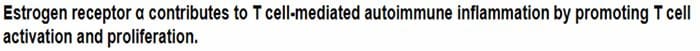

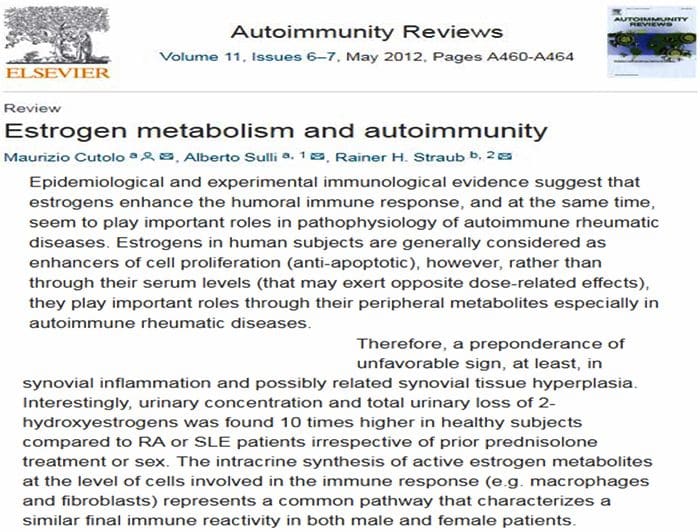

80% Of Patients With Autoimmune Disease Are Female

80% Of Patients With Autoimmune Disease Are Female

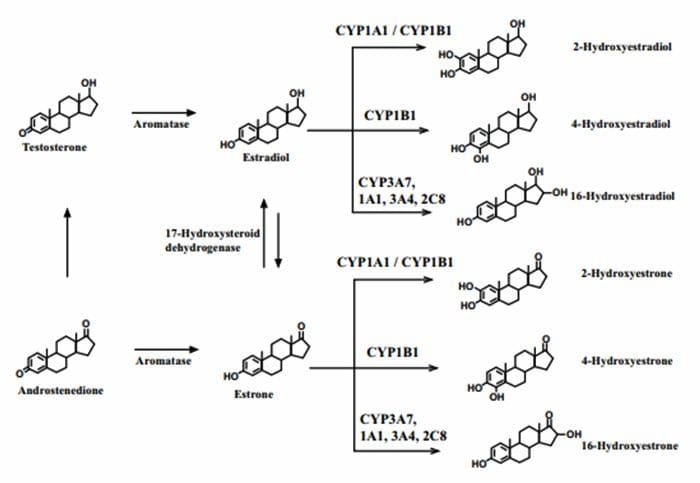

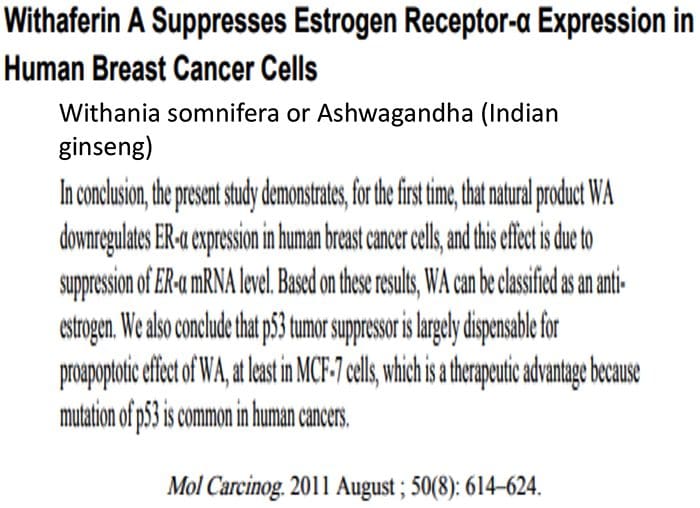

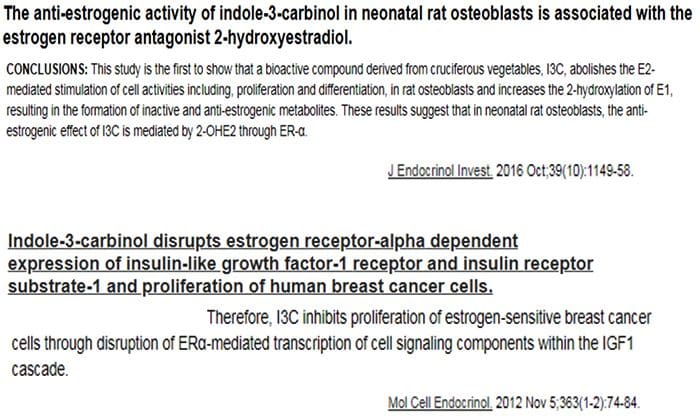

4?Hydroxyestrogens & DNA reactivity

4?Hydroxyestrogens & DNA reactivity

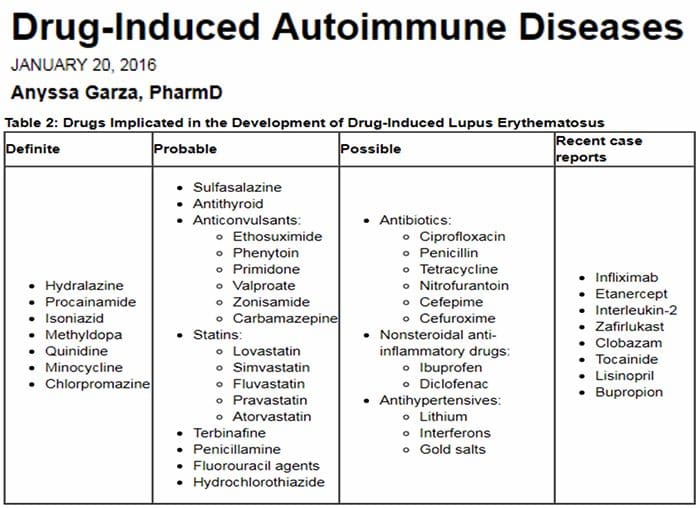

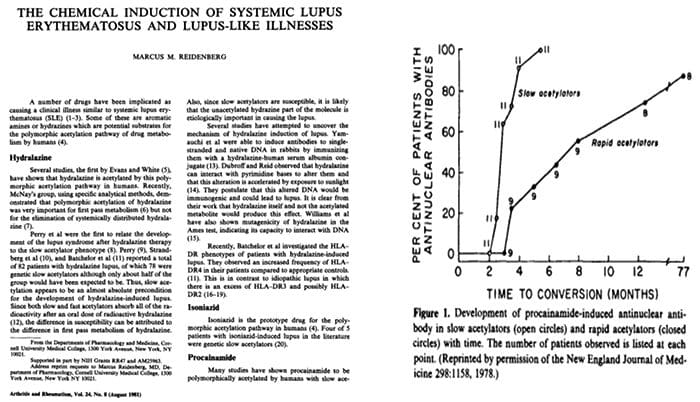

Relationship Of Hepatic Drug Detoxification To Anti?Nuclear Antibody Development

Relationship Of Hepatic Drug Detoxification To Anti?Nuclear Antibody Development

Endocrine Thyroid

Endocrine Thyroid Endocrine?Thyroid

Endocrine?Thyroid Musculoskeletal

Musculoskeletal Musculoskeletal & Kidney

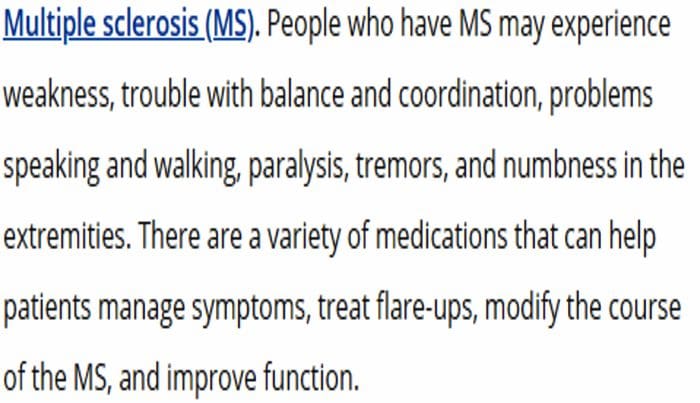

Musculoskeletal & Kidney Neurological

Neurological Autoimmunity

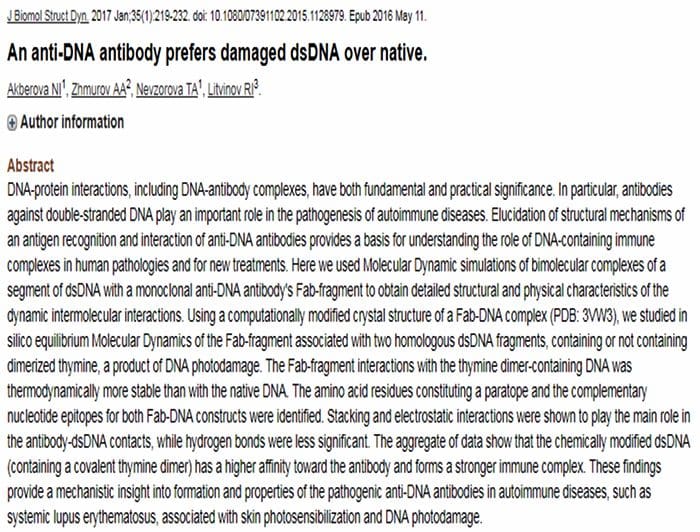

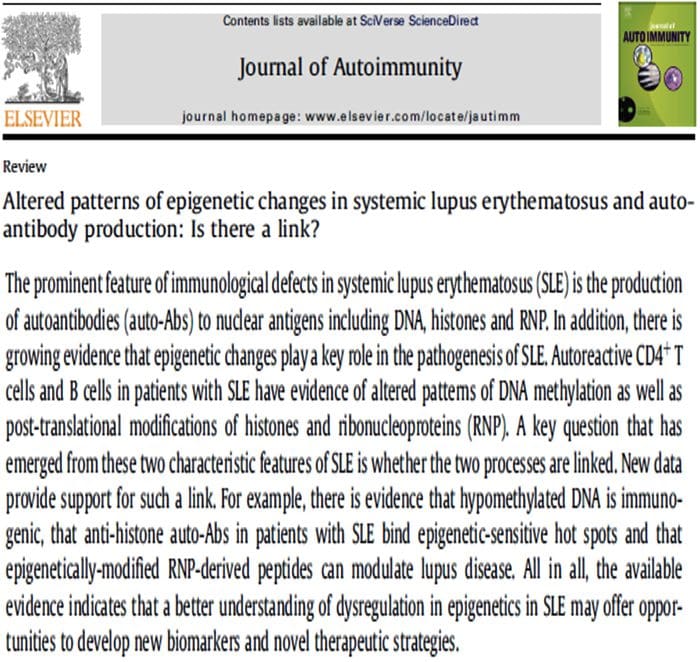

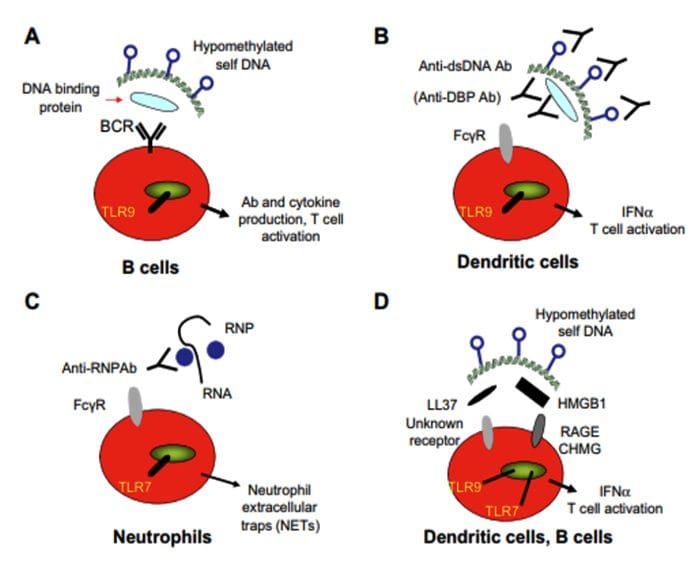

Autoimmunity Presence of Anti?Chromatin, DNA and RNA Antibodies

Presence of Anti?Chromatin, DNA and RNA Antibodies

What Biological Processes May Make Self Into Non?Self?

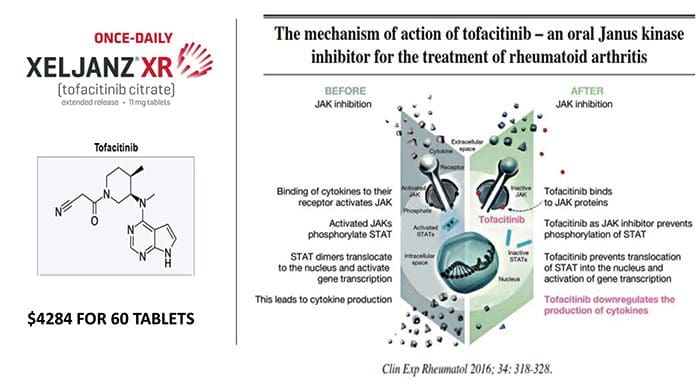

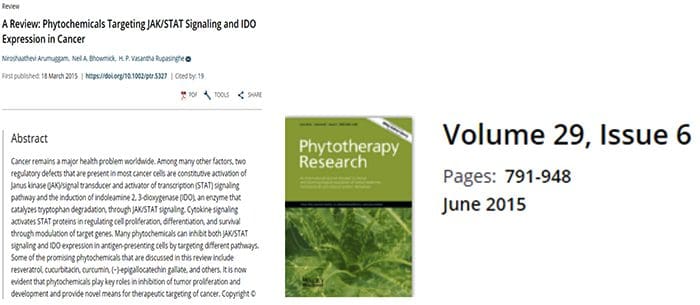

What Biological Processes May Make Self Into Non?Self? The Facts on Methotrexate For Rheumatoid Arthritis Treatment

The Facts on Methotrexate For Rheumatoid Arthritis Treatment

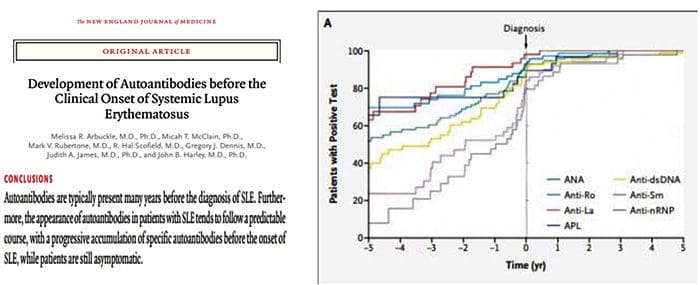

Autoantibodies Are Increasing At Least Five Years Before Diagnosis Of SLE

Autoantibodies Are Increasing At Least Five Years Before Diagnosis Of SLE

The Argument For Preventing Self From Becoming Non?Self

The Argument For Preventing Self From Becoming Non?Self

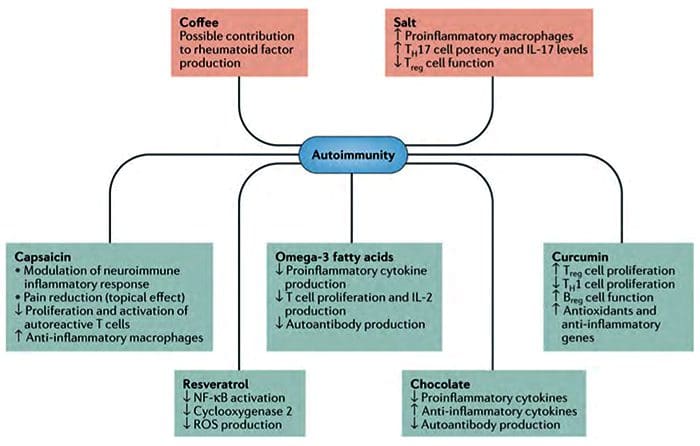

Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2017 Jun;13(6):348-358.

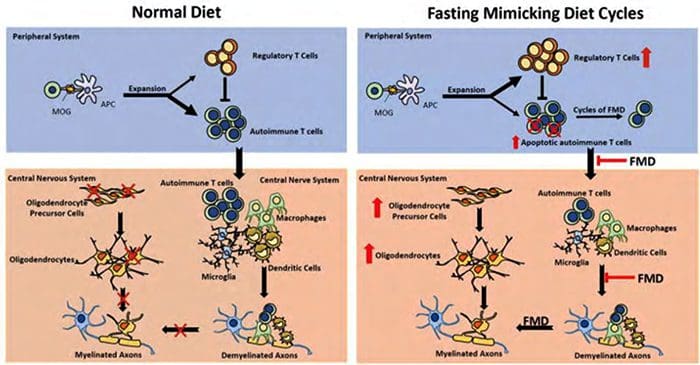

Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2017 Jun;13(6):348-358. Paolo Riccio, and Rocco Rossano ASN Neuro

Paolo Riccio, and Rocco Rossano ASN Neuro

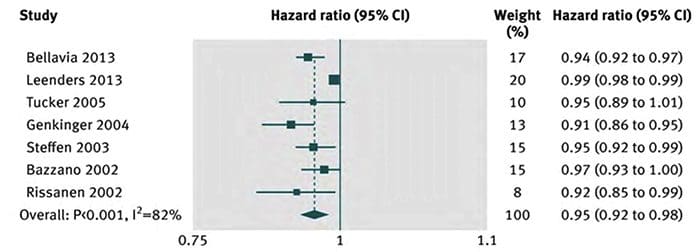

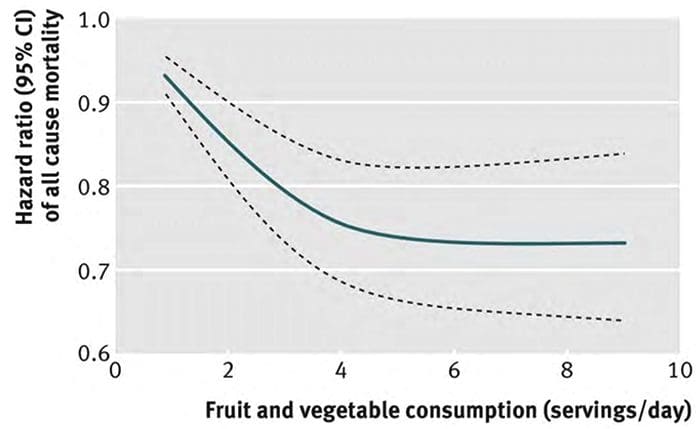

BMJ. 2014; 349: g4490.

BMJ. 2014; 349: g4490.

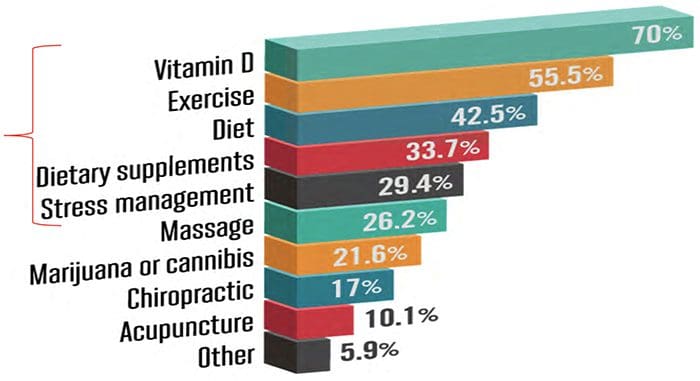

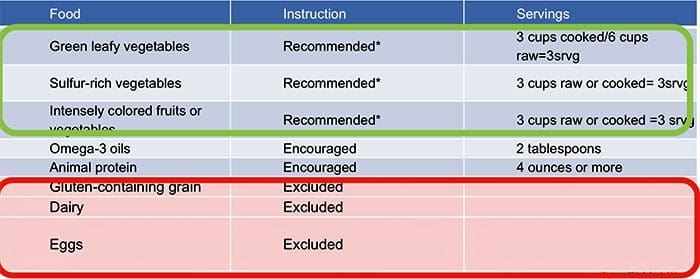

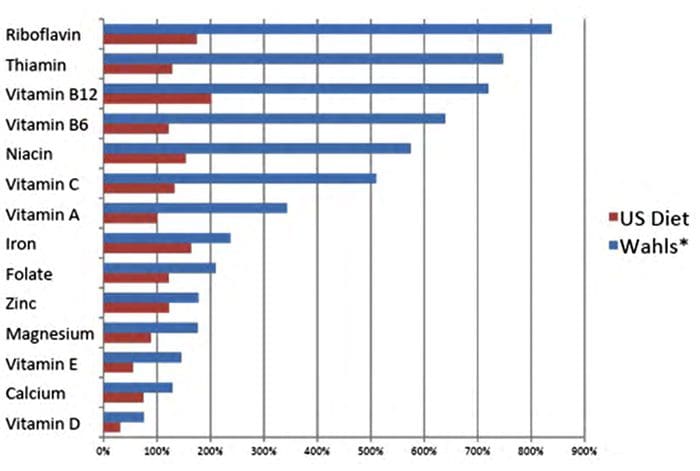

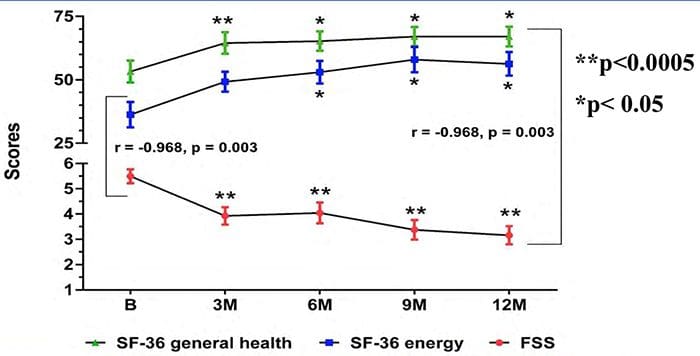

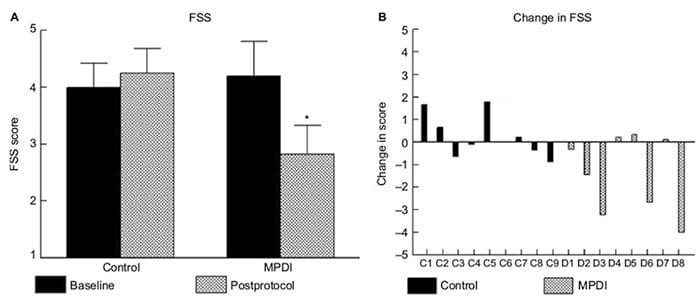

Reduce Fatigue

Reduce Fatigue

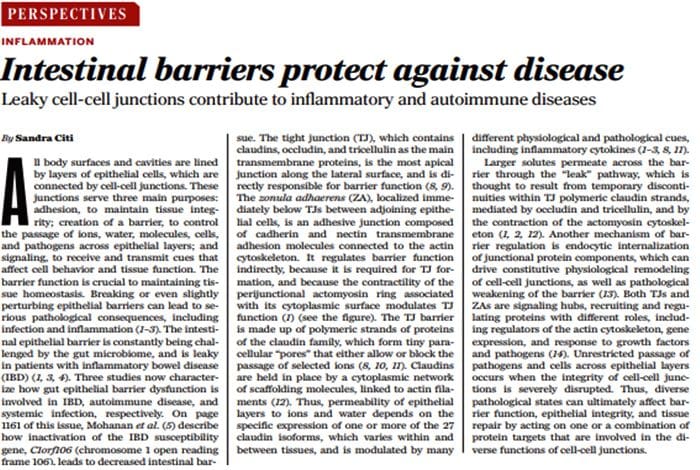

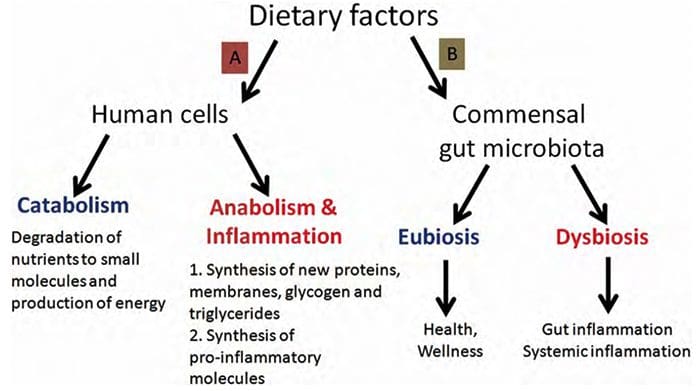

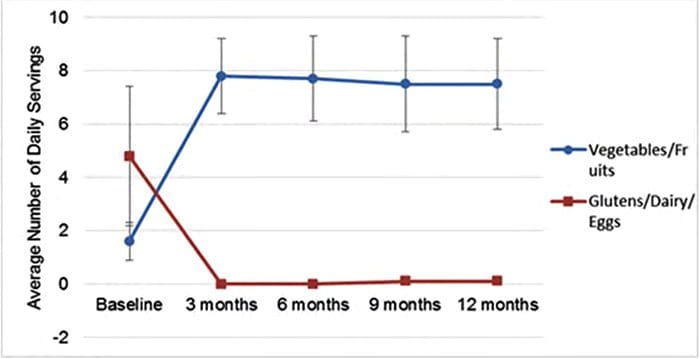

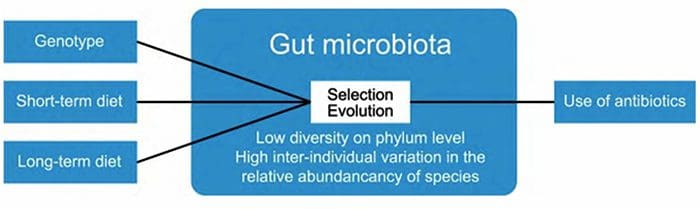

The composition of gut microbiota is influenced by multiple factors, such as diet and host genotype. Within the gut, ecological processes such as selection and evolution take place. The use of antibiotics reduces the numbers and diversity of gut microbiota.

The composition of gut microbiota is influenced by multiple factors, such as diet and host genotype. Within the gut, ecological processes such as selection and evolution take place. The use of antibiotics reduces the numbers and diversity of gut microbiota.