Mindfulness Interventions in Chronic Pain Treatment in El Paso, TX

Stress has become a new standard in today’s society, however, a huge proportion of the United States population has experienced a significant impact on their health due to the stress in their lives. Approximately 77 percent of Americans claim they suffer stress related physical ailments on a regular basis. Also, 73 percent report experiencing stress related emotional symptoms, such as anxiety and depression. Stress management methods and techniques, including chiropractic and mindfulness interventions, are a valuable treatment option for a variety of diseases. Before addressing the symptoms associated with stress, its essential to first understand what stress is, what are the signs and symptoms of stress, and how can stress impact health.

What is Stress?

Stress is a condition of emotional or mental pressure which result from issues, adverse scenarios, or exceptionally demanding circumstances. However, the nature of stress by definition makes it rather subjective. A stressful situation to one person may not be considered stressful to another. This makes it challenging to come up with a universal definition. Stress is much more often used to refer to its symptoms and those symptoms can be as varied as the men and women who experience them.

What are the Signs and Symptoms of Stress?

The signs and symptoms of stress can impact the whole body, both physically and emotionally. Common signs and symptoms of stress include:

- Sleep problems

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Muscle tension

- Lower back pain

- Gastrointestinal problems

- Fatigue

- Lack of motivation

- Irritability

- Headache

- Restlessness

- Chest pain

- Feelings of being overwhelmed

- Decrease or increase in sex drive

- Inability to focus

- Undereating or overeating

How can Stress Impact Health?

People can experience different signs and symptoms of stress. Stress itself doesn’t directly impact an individual’s health. Instead, it is a combination of the signs and symptoms of stress as well how the person handles those that adversely impact health.

Ultimately, stress may result in some very serious ailments including: heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and even certain cancers. Psychologically, stress can lead to social withdrawal and social phobias. It is also often directly linked to alcohol and drug abuse.

Chiropractic for Stress Management

Mindfulness interventions are common stress management methods and techniques which can help reduce the signs and symptoms of stress. According to several research studies, however, chiropractic care is an effective stress management treatment option, which together with mindfulness interventions, could help improve as well as manage stress.�Because the spine is the root of the nervous system, the health of your spine can determine how you will feel each day, both physically and emotionally. Chiropractic can help restore the balance of the body, aligning the spine, and decreasing pain.

A subluxation, or misalignment of the spine, can interfere with the way the nervous system communicates with the different parts of the body. This can lead to increased signs and symptoms of stress. A subluxation may also result in chronic pain, such as headaches, neck pain or back pain. The stress of a misalignment of the spine can aggravate the signs and symptoms of stress and make a person more susceptible to stress.�Correcting the alignment of the spine can help ease stress.

Regular chiropractic care can help effectively manage stress. Through the use of spinal adjustments and manual manipulations, a chiropractor can gently realign the spine, releasing the pressure being placed on the spinal vertebrae as well as reducing the muscle tension surrounding the spine. Furthermore, a balanced spine also helps boost the immune system, promotes better sleeping habits and helps to improve circulation, all of which are essential towards reducing stress. Finally, chiropractic care can “turn off” the flight or fight response which is commonly associated with stress, allowing the entire body to rest and heal.

Stress should not be ignored. The signs and symptoms of stress aren’t very likely to go away on their own. The purpose of the following article is to demonstrate an evidence-based review on the use of stress management methods and techniques along with mindfulness interventions in chronic pain treatment as well as to discuss the effects of these treatment options towards improving overall health and wellness. Chiropractic, physical rehabilitation and mindfulness interventions are fundamental stress management methods and/or techniques recommended for the improvement and management of stress.

Mindfulness Interventions in Physical Rehabilitation: A Scoping Review

Abstract

A scoping review was conducted to describe how mindfulness is used in physical rehabilitation, identify implications for occupational therapy practice, and guide future research on clinical mindfulness interventions. A systematic search of four literature databases produced 1,524 original abstracts, of which 16 articles were included. Although only 3 Level I or II studies were identified, the literature included suggests that mindfulness interventions are helpful for patients with musculoskeletal and chronic pain disorders and demonstrate trends toward outcome improvements for patients with neurocognitive and neuromotor disorders. Only 2 studies included an occupational therapist as the primary mindfulness provider, but all mindfulness interventions in the selected studies fit within the occupational therapy scope of practice according to the American Occupational Therapy Association�s Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process. Higher-level research is needed to evaluate the effects of mindfulness interventions in physical rehabilitation and to determine best practices for the use of mindfulness by occupational therapy practitioners.

MeSH TERMS: complementary therapies, mindfulness, occupational therapy, rehabilitation, therapeutics

Mindfulness interventions are frequently used in health care to assist patients in managing pain, stress, and anxiety and in targeting additional health, wellness, and quality-of-life outcomes. Although mindfulness practices originate from Buddhism, mindfulness interventions have become largely secular and are based on the philosophy that full and nonjudgmental experience of the present moment creates positive outcomes for mental and physical health (Williams & Kabat-Zinn, 2011). This paradigm assumes that many people experience a high volume of future- or past-focused thoughts that produce anxiety. Hence, mindfulness is the practice of refocusing away from these distractions and toward lived experiences.

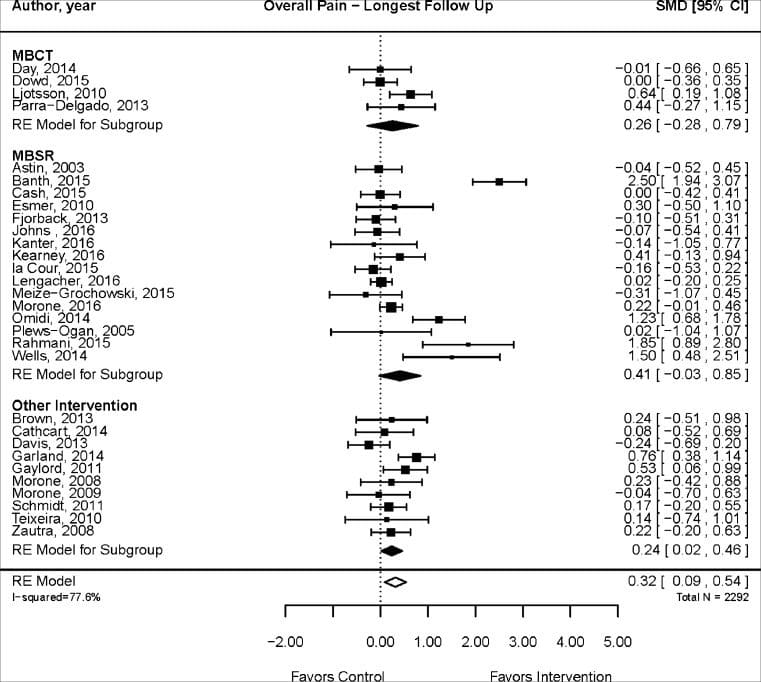

The prevalence of mindfulness interventions in health care has grown substantially in recent decades, and several types of mindfulness interventions have emerged. The first and most widely recognized mindfulness intervention is mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR; Kabat-Zinn, 1982). Initially called the stress reduction and relaxation program, MBSR was developed more than 30 years ago for patients with chronic pain and involves guided sitting meditation, mindful movement, and education on the effect of stress and anxiety on health and wellness. The evidence supporting mindfulness interventions in health care has grown since the inception of MBSR, and modern mindfulness interventions are shown to be effective at reducing pain severity (Reiner, Tibi, & Lipsitz, 2013), reducing anxiety (Shennan, Payne, & Fenlon, 2011), and enhancing well-being (Chiesa & Serretti, 2009).

Mindfulness-based interventions fit well with the strong emphasis on holism within occupational therapy practice (Dale et al., 2002). Specifically, valuing the mind�body whole is a core tenet that distinguishes occupational therapy practitioners from other health care providers (Bing, 1981; Kielhofner, 1995; Wood, 1998). Emerging literature suggests that mindfulness may enhance occupational engagement and be related to flow state (i.e., a state of timelessness within optimal experiences of activity engagement; Elliot, 2011; Reid, 2011). Mindfulness is both the meditative practice, which is an occupation itself, and a means to enhance the experience of occupations (Elliot, 2011). Moreover, a parallel exists between mindfulness practices and the occupational process of doing, being, and becoming (Stroh-Gingrich, 2012; Wilcock, 1999).

Mindfulness-based interventions in health care continue to grow in scope with the description of novel protocols, application of mindfulness to new populations, and targeting of diverse symptoms. The majority of current mindfulness literature focuses on helping people with mental health conditions and improving wellness in people, providing a wealth of evidence for occupational therapy practitioners who work in mental health or health promotion. However, the applicability and effect of mindfulness interventions for clients in rehabilitation for physical dysfunction are not as well established. Current literature that links mindfulness and occupational therapy is largely theoretical, and a translation to practice-based settings has yet to be fully explored. Therefore, the purpose of this review was to describe how mindfulness is currently used in physical rehabilitation, identify the potential applications of mindfulness interventions to occupational therapy practice, and illuminate gaps in knowledge to be explored in future research.

Method

Scoping reviews are rigorous review processes used to present the landscape of the literature on a broad topic, identify gaps in knowledge, and draw implications for further research and clinical application (Arksey & O�Malley, 2005). This type of review differs from a systematic review because it is not intended to answer questions about the efficacy of an intervention or provide specific recommendations for best practice. A scoping review is typically done in place of a systematic review when high-quality literature for a given topic is limited. Although the purpose and outcome of a scoping review differ from those of a systematic review, a systematic process is involved to ensure rigor and minimize bias (Arksey & O�Malley, 2005). A description of the methods used in this study for each of the systematic steps follows.

The question that guided this scoping review was, How is mindfulness being used in physical rehabilitation, and what are the implications for occupational therapy practice and research? Because the purpose of this review was to provide an overview of available literature, an exhaustive search using terms for all potential interventions or diagnoses was not used. Instead, we elected to combine the general key word mindfulness with each of the following major medical subheadings: therapeutics, rehabilitation, and alternative medicine. Searches were conducted in PubMed, CINAHL, SPORTDiscus, and PsycINFO and were limited to articles published in English before October 10, 2014 (i.e., the date the search was conducted). No additional limits were set, and no restrictions were placed on minimum level of evidence or study design.

Abstracts from the searches were compiled, duplicates were eliminated, and two reviewers independently screened all original abstracts. Initial inclusion criteria for abstract screening were a description of a mindfulness intervention, relevance to occupational therapy, and targeting of a disorder addressed in physical rehabilitation. A broad definition of mindfulness intervention was adopted to include any meditative practice, psychological or psychosocial intervention, or other mind�body therapeutic practice that directly mentioned or addressed mindfulness. Abstracts were considered relevant to occupational therapy if the diagnosis being evaluated was within the occupational therapy scope of practice. Disorder addressed in physical rehabilitation was defined as any illness, injury, or disability of the neurological, musculoskeletal, or other body system that could be treated within a medical or rehabilitation setting.

Any abstract identified as relevant by either author was brought to the full-text stage. In large part, these studies were conducted by scientists, psychologists, psychiatrists, or other medical doctors. Additionally, the interventions were often not implemented in settings where physical rehabilitation providers work. Therefore, to most appropriately answer the research question, final inclusion required that the study focus on an applied use of mindfulness in a rehabilitation context. This additional criterion was satisfied if the mindfulness intervention was provided by a rehabilitation professional (e.g., occupational therapist, physical therapist, speech therapist), was an addition or alternative to traditional rehabilitation, or was provided after traditional rehabilitation had failed. The two authors independently reviewed the full texts, and final study inclusion required agreement by both authors. Any disagreement on study selection was settled by deliberation ending in consensus.

For reporting, studies were primarily organized by type of physical disorder being targeted and secondarily sorted and described by type of mindfulness intervention and level of evidence. These data were summarized and are provided in the Results section to answer the first portion of the research question, that is, to describe how mindfulness is being used in physical rehabilitation. The interventions were compared with the �Types of Occupational Therapy Interventions� categories within the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process (American Occupational Therapy Association [AOTA], 2014) to determine how occupational therapy practitioners might use the interventions in clinical practice. Multiple conversations and coediting of this article between the two authors resulted in the final description of implications for occupational therapy practice and research.

Results

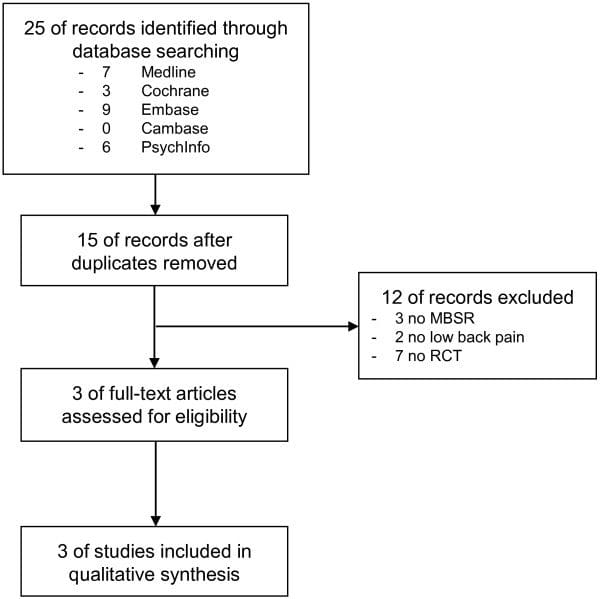

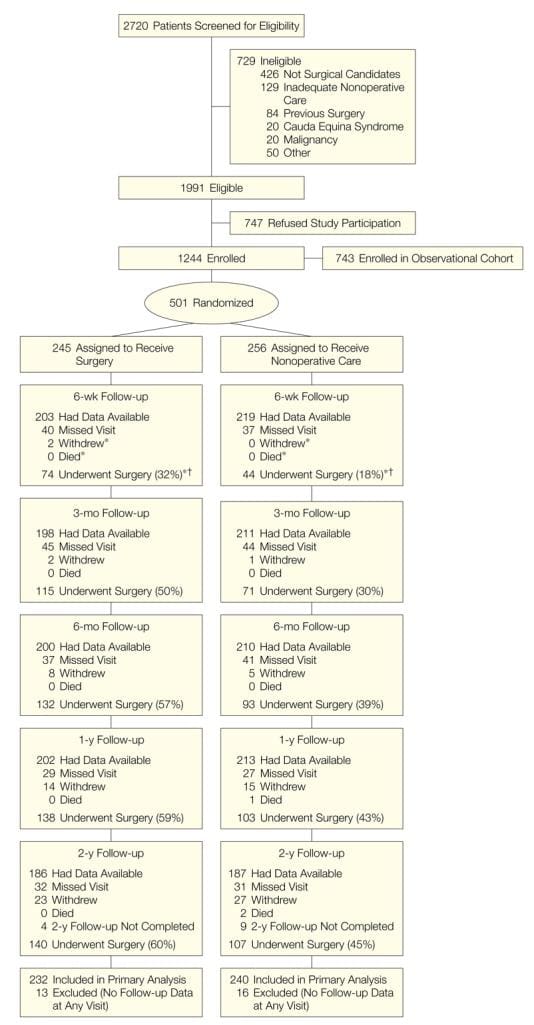

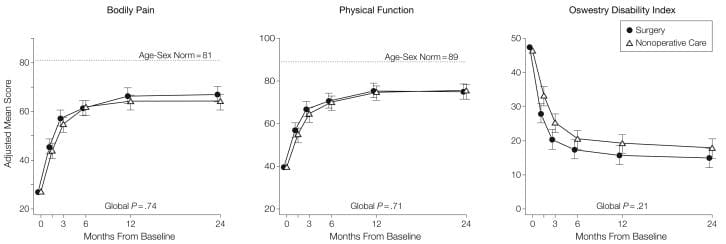

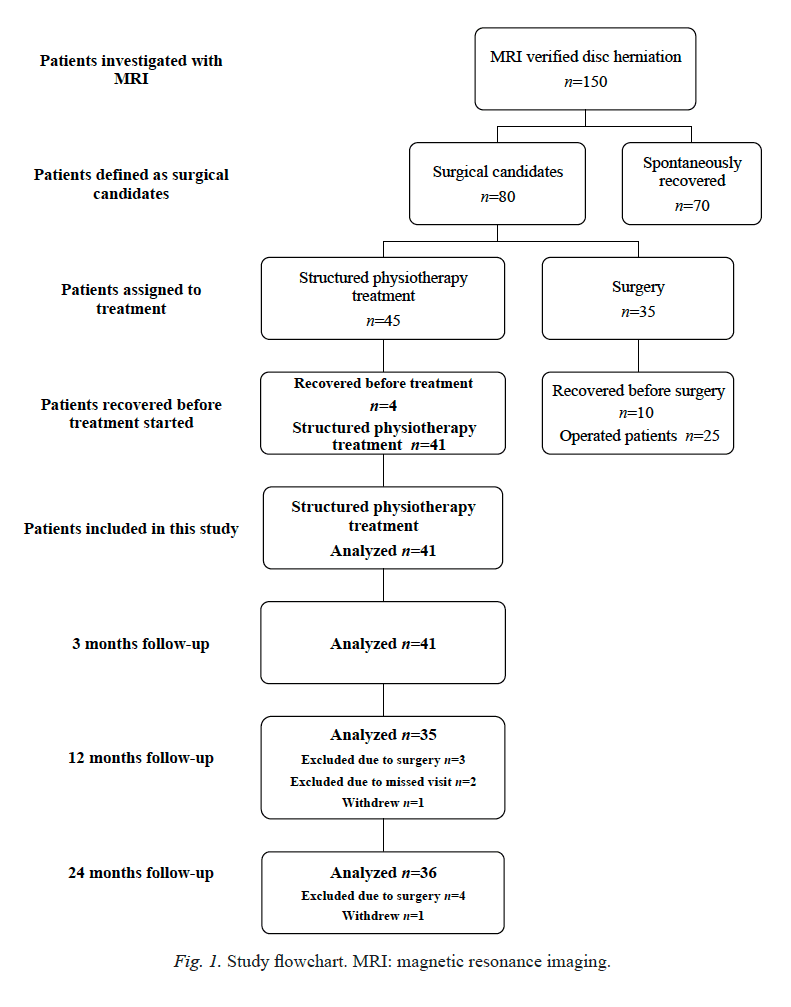

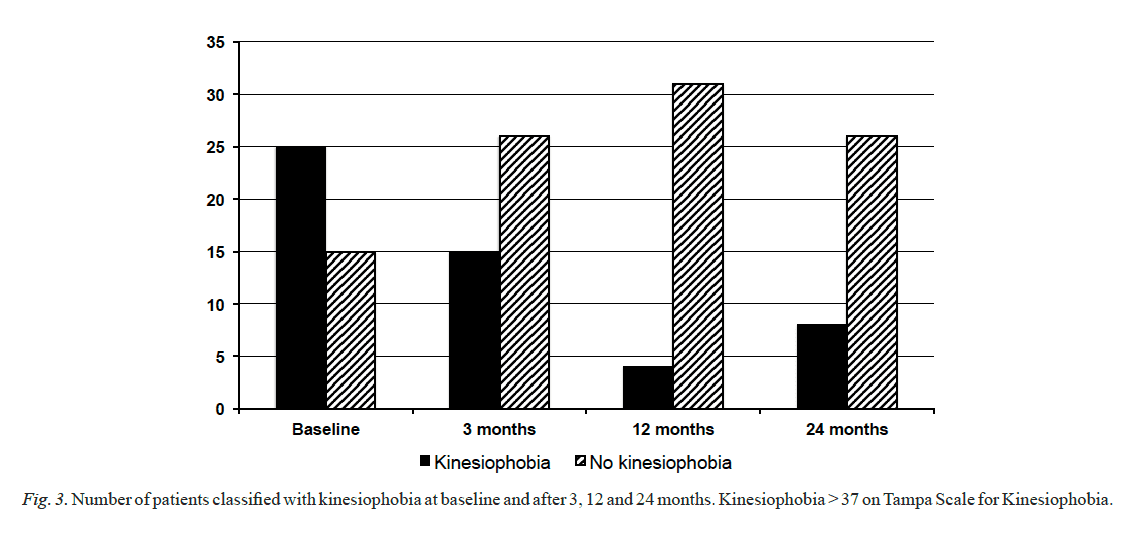

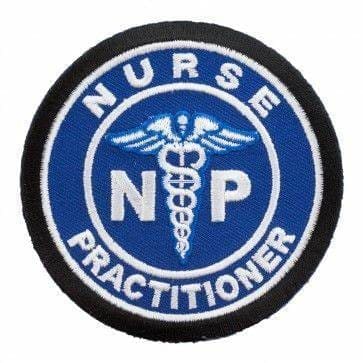

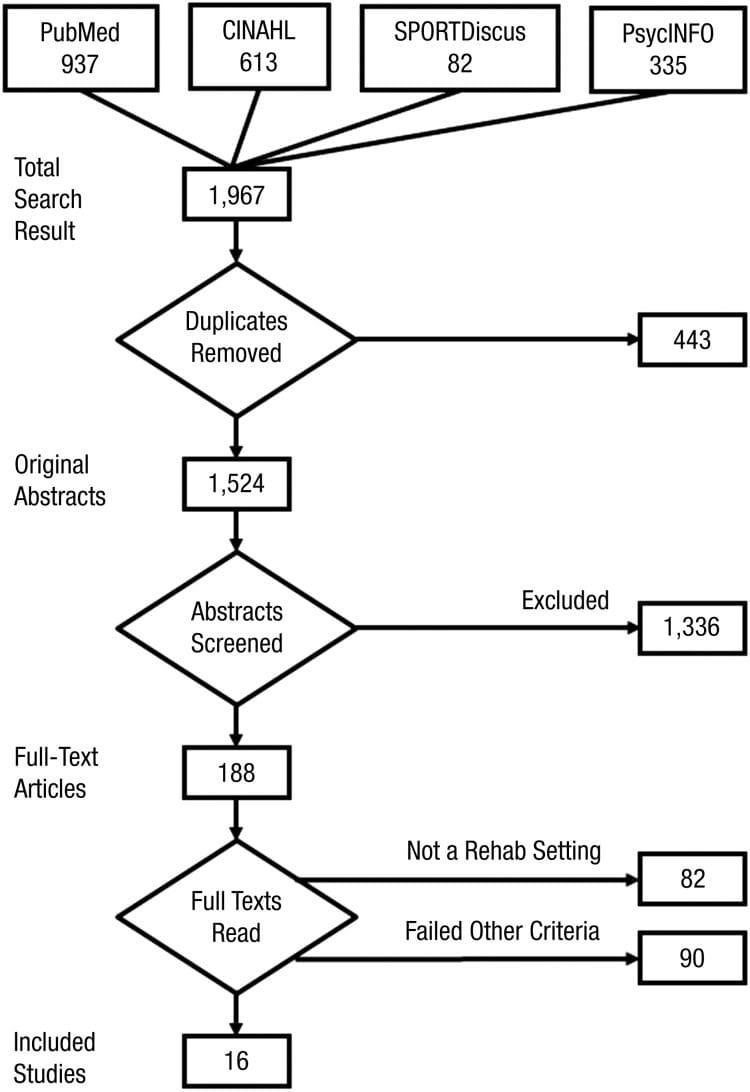

Results of the systematic search and review process are shown in Figure 1. The searches produced a total of 1,967 abstracts across the four databases. After 443 duplicates were removed, 1,524 original abstracts were screened, and 188 full texts were evaluated for inclusion. Exclusion at the abstract review phase was largely the result of diagnoses or interventions outside the occupational therapy scope (e.g., therapy for tinnitus) or interventions not targeting a physical disorder (e.g., anxiety disorder). At the study selection stage, full-text articles were excluded if they failed to describe an applied use of mindfulness within a rehabilitation context (n = 82) or failed to meet other initial inclusion criteria (n = 90). Sixteen studies met all criteria and were included in the data extraction and synthesis.

Figure 1: Search and inclusion flow diagram.

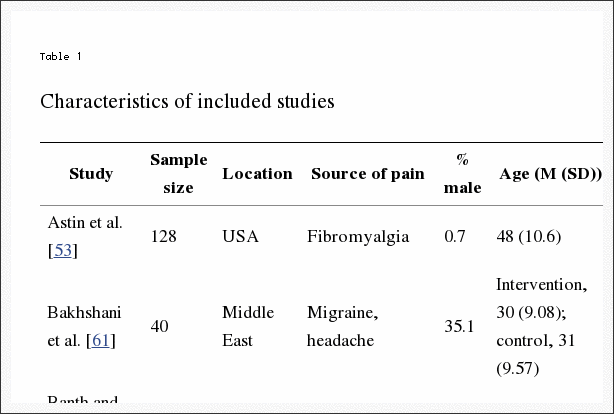

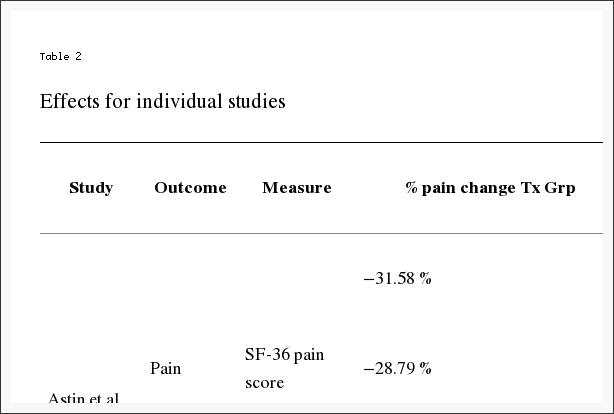

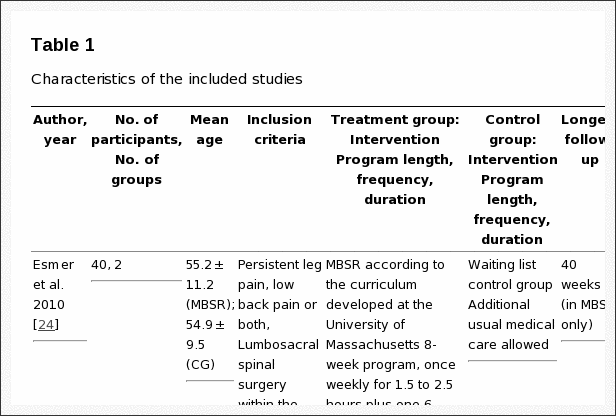

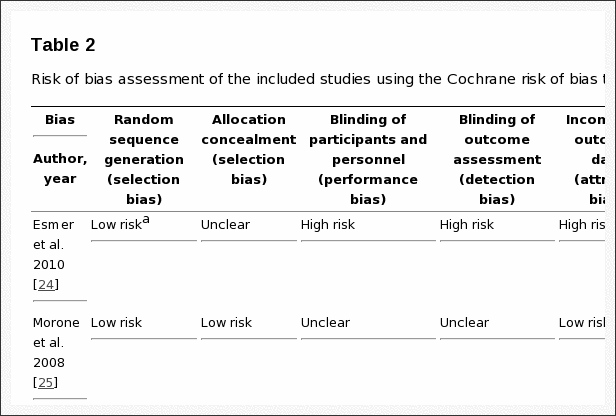

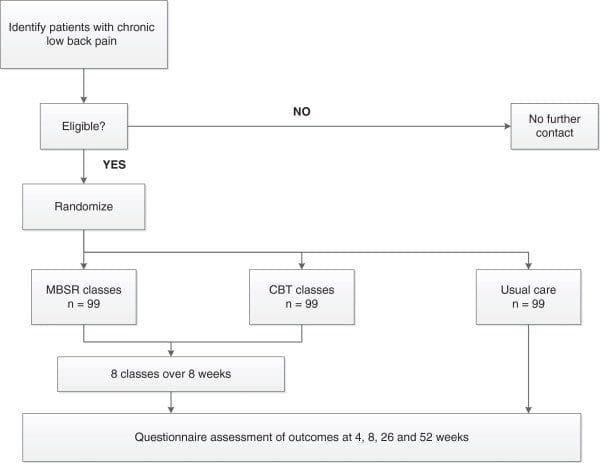

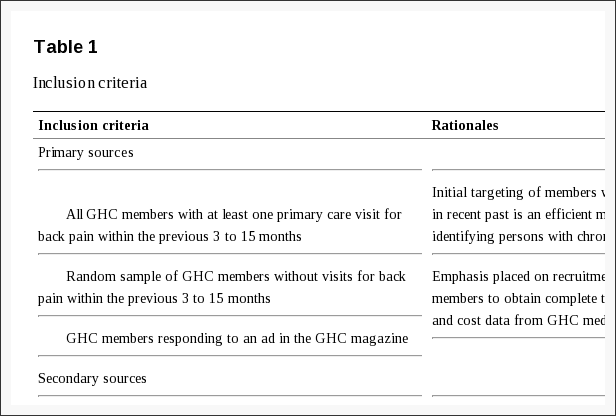

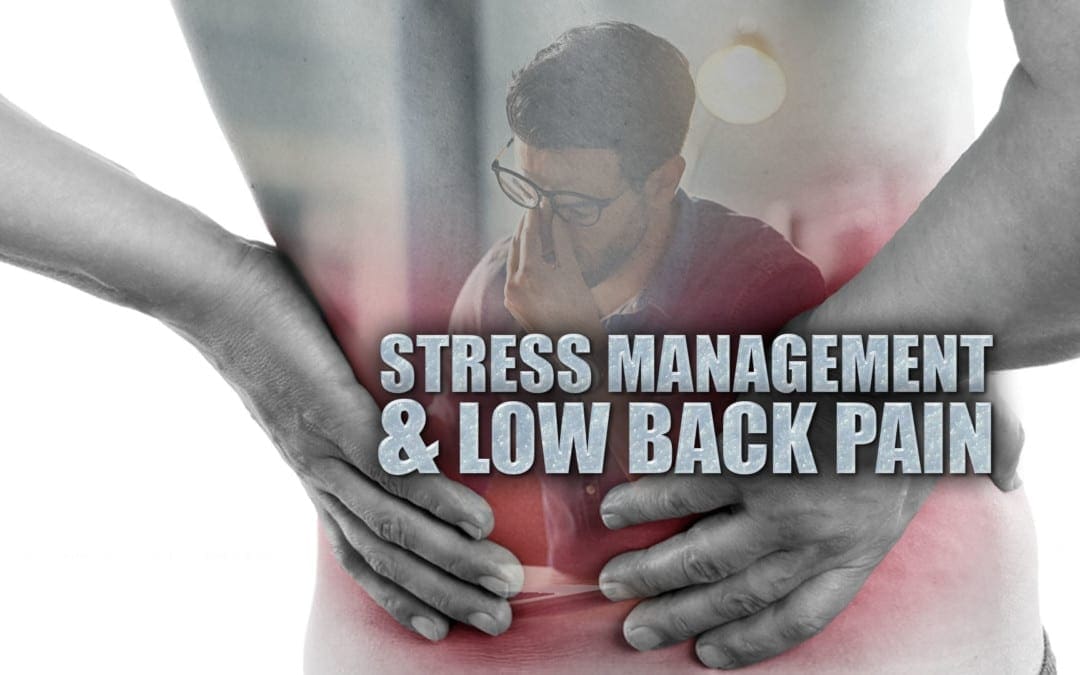

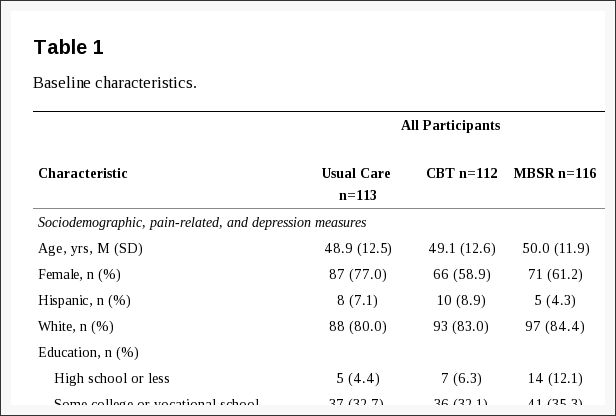

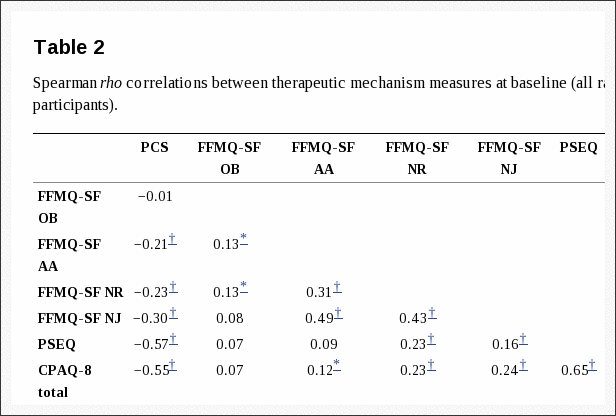

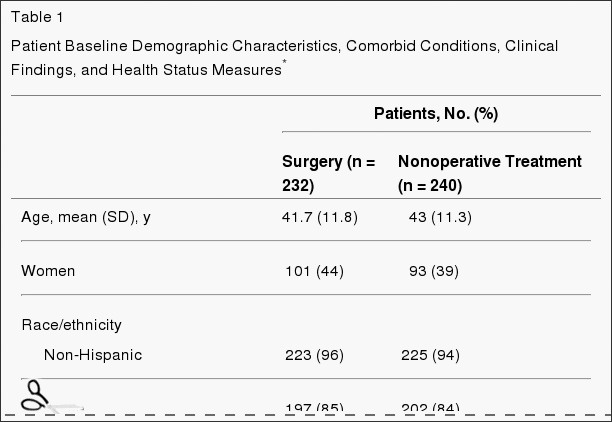

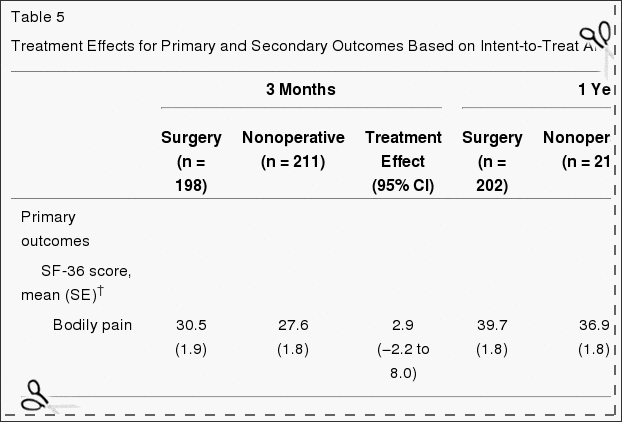

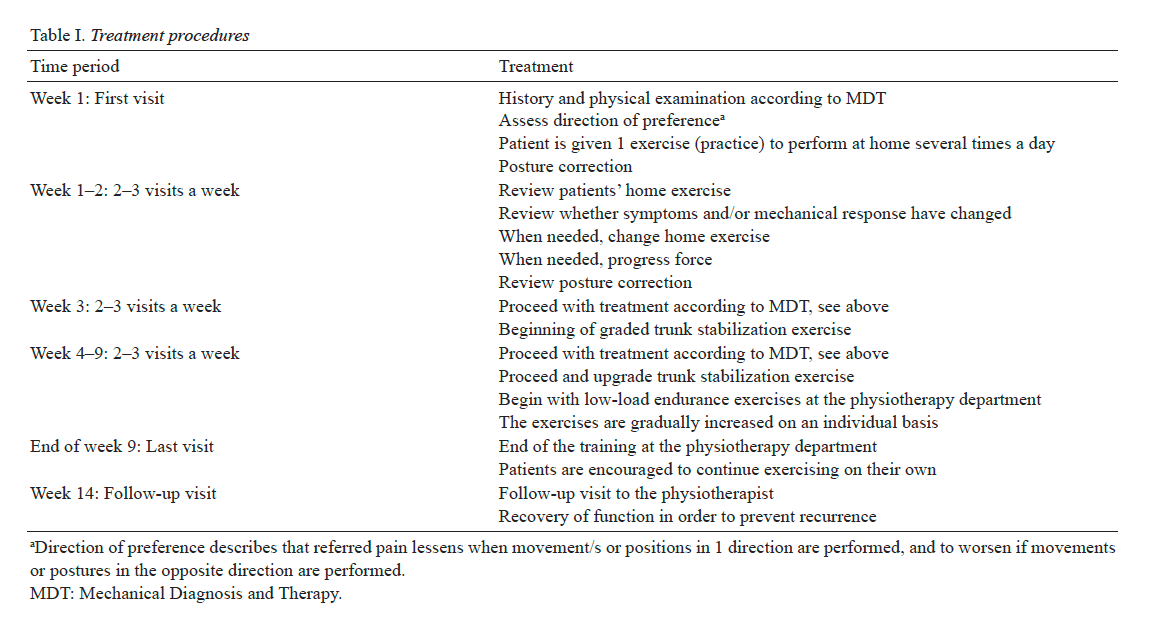

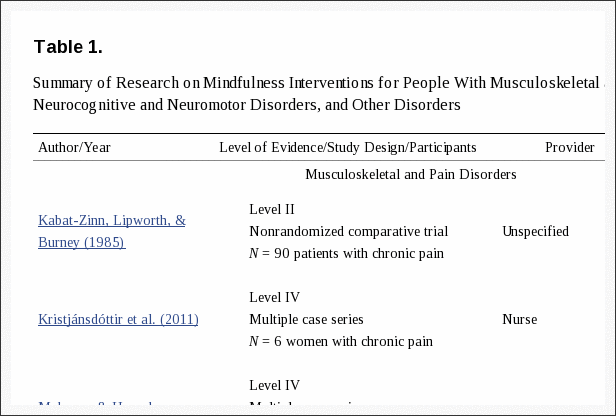

As shown in Table 1, 14 studies used experimental or quasi-experimental designs, including pretest�posttest (n = 6), multiple case series (n = 4), randomized trials (n = 2), retrospective cohort (n = 1), and a nonrandomized comparative trial (n = 1). Two expert opinion articles were also included because both added anecdotal evidence for the applied use of mindfulness in physical rehabilitation practice settings. Five of the 16 studies reported the involvement of occupational therapists on the study team, but only 2 of these studies specified that an occupational therapist provided the mindfulness intervention. The remaining 11 studies provided mindfulness interventions to participants either in conjunction with rehabilitation interventions not described as part of the study or after rehabilitation had failed. Mindfulness interventions included MBSR (n = 6), general mindfulness and meditation (n = 5), acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT; n = 2), and other study-specific techniques (n = 3). Physical disorders targeted by mindfulness interventions in the included studies were primarily categorized as musculoskeletal and pain disorders (n = 8), neurocognitive and neuromotor disorders (n = 6), or disorders of other body systems (n = 2).

Table 1: Summary of research on mindfulness interventions for people with musculoskeletal and pain disorders, neurocognitive and neuromotor disorders, and other disorders.

Common Mindfulness Interventions

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction. As referenced in Table 1, 3 studies used MBSR, each with an emphasis on meditation provided in a 2-hr group session, once a week for 8 wk. Three additional studies used an adapted MBSR protocol to meet the needs of the target population. Common adaptations of the MBSR protocol were to change the number of weeks the MBSR group met (Azulay, Smart, Mott, & Cicerone, 2013; B�dard et al., 2003, 2005) as well as to reduce the group size and session length (Azulay et al., 2013). The primary goal of MBSR and MBSR-based programs was to enhance trait-level mindfulness within the participants. Sessions included body scans (i.e., bringing attention to various parts of the body and the sensations felt), mindful yoga, guided mindful meditation, or education about stress and health. One or two people with intensive training in MBSR and who were practitioners of mindfulness themselves always facilitated MSBR sessions. Participants were expected to use recordings to meditate at home on a daily basis. Studies that implemented MBSR used it as a primary intervention to enhance mindfulness through mindfulness practices that patients were expected to integrate into their daily lives. This approach cast mindfulness as a new meaningful occupation for participants facilitated by the intervention. Therefore, the description and use of MBSR in these studies match with occupations and activities, education and training, and group interventions within occupational therapy practice (AOTA, 2014).

General Mindfulness. Five studies applied mindfulness principles generally, failed to fully describe the mindfulness portion of their intervention, or used mindfulness components (e.g., body scan only or guided meditation only) within a comprehensive rehabilitation intervention (see Table 1). Interventions varied widely between group or individual formats, in duration and frequency of sessions, and in duration of the full course of treatment. General mindfulness techniques were used as an opening to, as a closing to, or in parallel with traditional rehabilitation treatments. Therefore, the application of mindfulness was individually targeted to meet the specific needs and goals of clients. Examples of these goals included occupational engagement, engagement in therapy, reduced anxiety, awareness of bodily sensations, and nonjudgmental attitude. Given the holistic targets, general mindfulness interventions as used in these studies would be described as activities, education, or preparatory methods and tasks (AOTA, 2014).

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. ACT is a psychological intervention stemming from clinical behavioral analysis and mindfulness principles. Two studies implemented ACT with different strategies. In 1 study (McCracken & Guti�rrez-Mart�nez, 2011), an intensive intervention was provided to participants in a group setting, 5 days per week, 6 hr per day, over a 4-wk interval. The other study (Mahoney & Hanrahan, 2011) integrated ACT as part of individual routine physical therapy interventions. In both studies, the primary goals of ACT were to improve psychological flexibility and engagement in therapy through pain acceptance and buffering of other psychological experiences. Similar to the integrative use previously described for general mindfulness, ACT was also used in these studies as activities, education, or preparatory methods and tasks (AOTA, 2014).

Targets of Mindfulness Interventions

Musculoskeletal and Pain Disorders. Musculoskeletal and pain disorders targeted by mindfulness interventions included chronic musculoskeletal pain (n = 6), work-related musculoskeletal injury (n = 1), and knee surgery (n = 1). Five of the 6 studies using mindfulness for chronic pain were experimental. In 3 of these studies, a significant reduction in pain severity was found after participation in mindfulness interventions (Kabat-Zinn, Lipworth, & Burney, 1985; McCracken & Guti�rrez-Mart�nez, 2011; Zangi et al., 2012). One randomized trial contrasted with the other studies; Wong et al. (2011) found that pain was reduced over time, but the amount of pain reduction was not significantly different between clients receiving the mindfulness intervention and a control group. The fifth experimental study (Kristj�nsd�ttir et al., 2011) piloted a mindfulness intervention by using a mobile phone application. This study�s sample size was not large enough to evaluate a significant change in the outcome measures; however, the participants reported that the mobile mindfulness intervention was helpful and appropriate for treating their symptoms. Although these studies demonstrated varied results in reducing pain severity, secondary outcomes such as increased acceptance of pain, improved functioning with pain, and decreased distress produced larger effect sizes and were consistently significant.

A retrospective study (Vindholmen, H�igaard, Espnes, & Seiler, 2014) sought to predict treatment outcomes based on the trait-level mindfulness of patients at a vocational rehabilitation center receiving therapeutic interventions for work-related musculoskeletal disorders. The observational facet of trait-level mindfulness was found to significantly predict time until return to work, but only for highly educated patients. The authors noted that mindfulness interventions may moderate quality of life, which was a significant predictor of time until return to work for all participants.

Two studies, 1 with Level IV (i.e., case series; Mahoney & Hanrahan, 2012) and 1 with Level V (i.e., expert opinion; Pike, 2008) evidence, suggested that combining traditional therapeutic rehabilitation interventions with mindfulness for patients with musculoskeletal and pain disorders has benefits. Clients receiving ACT integrated into their physical therapy sessions after knee surgery reported that the mindfulness intervention was helpful to their rehabilitation process and increased their engagement in therapy (Mahoney & Hanrahan, 2012). In his commentary, Pike (2008) argued for implementing mindfulness interventions in combination with physical therapy for patients who suffer from chronic pain, noting that mindfulness is similar to more widely used awareness-based interventions (e.g., Pilates). Similar to the positive reception noted by Mahoney and Hanrahan (2012), Pike noted that integrating mindfulness into his physical therapy practice had proven to be clinically useful and well tolerated by patients. He hypothesized that the mechanism of mindfulness interventions may either directly reduce pain or improve functional outcomes despite pain, concepts validated by the experimental studies previously discussed in this section.

Neurocognitive and Neuromotor Disorders. Studies using mindfulness interventions for people with neurocognitive and neuromotor disorders included participants with diagnoses of aphasia (n = 1), traumatic brain injury (TBI; n = 4), and developmental coordination disorder (n = 1). Orenstein, Basilakos, and Marshall (2012) found no change attributed to a mindfulness intervention on divided attention tasks or symptoms of aphasia when used with 3 clients. However, 3 pretest�posttest studies using mindfulness interventions for patients with TBI showed more promising results. Azulay et al. (2013) reported a trend (p = .07) toward improved cognitive functioning, with moderate effect sizes (d = 0.31 and 0.32). B�dard et al. (2003) found trends toward reduced symptom distress and improved physical health, with small to moderate effect sizes (0.296 < d < 0.32). They also demonstrated significant improvements in secondary measures such as self-efficacy, quality of life, and mental health. Moreover, a 12-mo postintervention follow-up of their 2003 study showed significant maintenance or improvement in patients with TBI across time in vitality, emotional role, and mental health, but fluctuating pain (B�dard et al., 2005). Of note is that although participants reported that they valued the mindfulness intervention, gender played a role in recruitment and retention because most young men either chose to not participate in or dropped out of the study (B�dard et al., 2005).

In Meili and Kabat-Zinn (2004), Meili, a woman who sustained a TBI, recounted that mindfulness was central to her journey of healing. Using Meili�s experience as an example, Kabat-Zinn asserted that helping patients understand, accept, and adjust to their illness or disability through both inner adjustment to new bodily experiences, or mindfulness, and external restoration of physical functioning, or physical rehabilitation, are essential to the healing process. Moreover, Kabat-Zinn stated that occupational therapy practitioners and other rehabilitation professionals are well equipped to implement mindfulness interventions because these interventions complement their existing practice of facilitating the outer work of healing the body. Adding mindfulness interventions would be clinically appropriate to foster the inner work necessary for patients to heal. Jackman (2014) also suggested that mindfulness is appropriate as part of the rehabilitative process. Jackman discussed the use of mindfulness in occupational therapy for children with developmental coordination disorder. Children who participated in mindfulness-enhanced therapy improved on at least one component of motor coordination. This therapy also helped parent�child dyads meet their self-directed goals.

Other Conditions. Two additional studies targeted physical diagnoses that were not explicitly musculoskeletal or neuromotor. In the first, MBSR was provided to women with urge-predominant urinary incontinence by an occupational therapist who had received intensive training in mindfulness (Baker, Costa, & Nygaard, 2012). Seven women who had an average of 4.14 episodes of urinary incontinence per day participated in an 8-wk MBSR group. In contrast to other studies that combined mindfulness with traditional rehabilitation, participants in this study received no other treatment or traditional interventions for urinary incontinence (e.g., pelvic floor muscle exercises, bladder education). At posttest, participants had significantly fewer episodes (p = .005), averaging 1.23 per day. Although limited by a small sample size and lack of a control group, this study demonstrated preliminary support for stand-alone mindfulness interventions provided by occupational therapists for a physical condition.

The second study used mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in the rehabilitation of vestibular dysfunction and dizziness (Naber et al., 2011). In this study, group-based mindfulness components were nested within standard vestibular rehabilitation practices, dialectical behavioral therapy, and cognitive�behavioral therapy over five biweekly sessions. In addition, participants met individually with a physical therapist who provided personalized exercises. Significant improvement in vestibular symptoms, including functional level, impairment, coping, and skill use (p < .0001), was noted.

Dr. Alex Jimenez’s Insight

Mindfulness interventions, such as mindfulness-based stress reduction, general mindfulness and acceptance and commitment therapy, are prevalent stress management methods and techniques frequently used in health care to help�relieve symptoms of stress, mental health issues and physical pain as well as to address and treat a variety of symptoms and diseases. Mindfulness interventions are believed to increase the outcome measures of alternative and complementary treatment options. Chiropractic care is another popular stress management option which can help improve as well as manage stress. The use of mindfulness interventions and chiropractic care with other treatments, such as physical rehabilitation, has been determined to increase their results. The article above demonstrated evidence-based results on the effectiveness of mindfulness interventions for symptoms of stress, including chronic pain.

Discussion

This scoping review describes how mindfulness is used in physical rehabilitation, identifies implications for occupational therapy, and illuminates gaps in current research. The studies included in the review provide preliminary support that mindfulness interventions can improve urinary incontinence, chronic pain, and vestibular functioning. These studies also show a promising trend toward improved outcomes for cognitive and behavior targets for patients with TBI. Across the studies, the strongest findings were for improvements in adaptation to illness or disability such as self-efficacy for disease management, increased quality of life, and acceptance of pain symptoms. In addition, mindfulness interventions for these outcomes not only were immediately effective but also maintained effectiveness at follow-up at a clinically significant level. This result suggests that adaptation-based outcomes are an important complement to function- and symptom-based outcomes in clinical mindfulness research. Moreover, patient appraisals of mindfulness interventions were positive, and no studies reported adverse or negative effects.

Occupational therapists were the primary providers of mindfulness interventions in 2 studies (Baker et al., 2012; Jackman, 2014). Although these studies showed promising results, both were limited by small sample size and lack of control conditions. In addition, Jackman (2014) failed to report numeric values for the findings, limiting interpretation. In 3 additional studies, occupational therapists had an ancillary role in providing mindfulness interventions (McCracken & Guti�rrez-Mart�nez, 2011; Vindholmen et al., 2014; Zangi et al., 2012). However, because of the complementary nature of the interventions with the occupational therapy scope of practice (AOTA, 2014) and the manner in which they were implemented, occupational therapy practitioners could have been active providers of the mindfulness interventions in these studies, highlighting the feasibility of integrating mindfulness into occupational therapy practice in future research. Moreover, although MBSR was the primary intervention that promoted engagement in mindfulness as an occupation, general mindfulness interventions and ACT also served as appropriate activity-based, preparatory, and educational interventions in these studies. Given the results of these studies and support from additional literature describing the use of mindfulness by occupational therapists (Moll, Tryssenaar, Good, & Detwiler, 2013; Stroh-Gingrich, 2012), further investigation of best practices for integrating mindfulness techniques into physical rehabilitation is warranted.

Although the literature suggests that mindfulness interventions can have positive effects in physical rehabilitation, substantial limitations exist in the current evidence. First, the majority of the positive studies are limited by their study design, being, at best, Level III evidence (i.e., cohort design). In contrast, an appropriately powered randomized controlled trial found a significant pretest�posttest effect of mindfulness interventions on pain reduction but also noted a similar reduction in pain for control group participants (Wong et al., 2011). Second, the wide variability in mindfulness intervention protocols makes it challenging to reach any general conclusions about intervention effectiveness. Finally, many studies overrepresented middle-aged White women, limiting interpretation of the acceptability of mindfulness interventions by or their effects in other demographics. Specifically, B�dard et al. (2005) noted decreased interest and adherence to their mindfulness intervention by male participants.

More information is needed to understand best practices for integration of mindfulness into occupational therapy practice. Specifically, the mindfulness interventions included in this review were generally complex, used a standardized protocol, were not fully integrated with standard rehabilitation interventions, and required intensive training for providers. Thus, further investigation is needed to:

- Establish the effectiveness of mindfulness interventions in various settings and patient populations with physical diagnoses in high-level, randomized trials;

- Examine the utility of training methods for occupational therapy practitioners in the delivery of mindfulness interventions for physical disorders as part of professional curricula, through continuing education programs or other postprofessional training;

- Describe best practices for clinical integration of mindfulness into occupational therapy practice; and

- Explore the implications related to reimbursement for and cost-effectiveness of the delivery of mindfulness interventions in occupational therapy practice.

Implications for Occupational Therapy Practice

The results of this study have the following implications for occupational therapy practice:

- Mindfulness in physical rehabilitation is primarily used to help clients with chronic pain and TBI adapt to illness and disability, which promotes functional recovery as complementary to symptom remediation.

- Mindfulness for physical disorders has yet to be substantiated as an evidence-based intervention within occupational therapy; however, promising preliminary evidence exists, and current mindfulness protocols fit within the occupational therapy scope of practice as preparatory, activity, or occupation-based interventions.

- Higher level research is needed to address the substantial limitations in current efficacy studies on mindfulness for physical conditions and to determine best practices for the use of mindfulness in physical rehabilitation by occupational therapy practitioners.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks for the support and guidance received from Dr. Gelya Frank. Work on this review was partially supported by Grant No. K12�HD055929, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Rehabilitation Research Career Development Program. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health. Portions of this work were presented at the 2015 Occupational Therapy Summit of Scholars in Los Angeles, CA.

Footnotes

Indicates studies that were included in the scoping review for this article.

Contributor Information

Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4834757/

In conclusion,�although stress is common in today’s society, stress can lead to a variety of physical and emotional diseases. Stress management methods and techniques are growing as popular treatment options to treat stress and its associated ailments, including chronic pain. Chiropractic care helps reduce stress by correcting subluxations, or spinal misalignments, to release pressure on the vertebrae and reduce muscle tension. The article above also demonstrates the effectiveness of mindfulness interventions in physical rehabilitation, although further research studies are needed. Information referenced from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic as well as to spinal injuries and conditions. To discuss the subject matter, please feel free to ask Dr. Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

Curated by Dr. Alex Jimenez

Additional Topics: Back Pain

According to statistics, approximately 80% of people will experience symptoms of back pain at least once throughout their lifetimes. Back pain is a common complaint which can result due to a variety of injuries and/or conditions. Often times, the natural degeneration of the spine with age can cause back pain. Herniated discs occur when the soft, gel-like center of an intervertebral disc pushes through a tear in its surrounding, outer ring of cartilage, compressing and irritating the nerve roots. Disc herniations most commonly occur along the lower back, or lumbar spine, but they may also occur along the cervical spine, or neck. The impingement of the nerves found in the low back due to injury and/or an aggravated condition can lead to symptoms of sciatica.

EXTRA IMPORTANT TOPIC: Managing Workplace Stress

MORE IMPORTANT TOPICS: EXTRA EXTRA: Choosing Chiropractic? | Familia Dominguez | Patients | El Paso, TX Chiropractor