by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Diets, Fitness, Gastro Intestinal Health, Gut and Intestinal Health

When it comes to stomach discomfort during exercise, forget that old adage “no pain, no gain.” New research suggests that excessive strenuous exercise may lead to gut damage.

“The stress response of prolonged vigorous exercise shuts down gut function,” said lead author Ricardo Costa.

“The redistribution of blood flow away from the gut and towards working muscles creates gut cell injury that may lead to cell death, leaky gut, and systemic immune responses due to intestinal bacteria entering general circulation,” Costa added. He’s a senior researcher with the department of nutrition, dietetics and food at Monash University in Australia.

Researchers observed that the risk of gut injury and impaired function seems to increase along with the intensity and duration of exercise.

The problem is dubbed “exercise-induced gastrointestinal syndrome.” The researchers reviewed eight previously done studies that looked at this issue.

Two hours appears to be the threshold, the researchers said. After two hours of continuous endurance exercise when 60 percent of an individual’s maximum intensity level is reached, gut damage may occur. Costa said that examples of such exercise are running and cycling.

He said heat stress appears to be an exacerbating factor. People with a predisposition to gut diseases or disorders may be more susceptible to such exercise-related health problems, he added.

Dr. Elena Ivanina is a senior gastroenterology fellow at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. She wasn’t involved with this research but reviewed the study. She said that normal blood flow to the gut keeps cells oxygenated and healthy to ensure appropriate metabolism and function.

If the gut loses a significant supply of blood during exercise, it can lead to inflammation that damages the protective gut lining. With a weakened gastrointestinal (GI) immune system, toxins in the gut can leak out into the systemic circulation — the so-called “leaky gut” phenomenon, Ivanina said.

But, she underscored that exercise in moderation has been shown to have many protective benefits to the gut.

“Specifically, through exercise, patients can maintain a healthy weight and avoid the consequences of obesity,” she said. Obesity has been associated with many GI diseases, such as gallbladder disease; fatty liver disease; gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD); and cancer of the esophagus, stomach, liver and colon. Regular moderate physical activity also lowers the risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and depression.

To prevent exercise-related gut problems, Costa advised maintaining hydration throughout physical activity, and possibly consuming small amounts of carbohydrates and protein before and during exercise.

Ivanina said preventive measures might help keep abdominal troubles in check. These include resting and drinking enough water. She also suggested discussing any symptoms with a doctor to ensure there is no underlying gastrointestinal disorder.

Costa recommended that people exercise within their comfort zone. If you have stomach or abdominal pain, “this is a sign that something is not right,” he said.

Individuals with symptoms of gut disturbances during exercise should see their doctor.

The study authors advised against taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs — including ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) or naproxen sodium (Aleve) — before working out.

Costa said there’s emerging evidence that a special diet — called a low FODMAP diet — leading up to heavy training and competition may reduce gut symptoms. FODMAP stands for fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols. FODMAPs are specific types of carbohydrates (sugars) that pull water into the intestinal tract.

The International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders suggests consulting a dietitian familiar with FODMAP diets. Such diets can be difficult to initiate properly on your own, the foundation says.

Costa also said there’s no clear evidence that dietary supplements — such as antioxidants, glutamine, bovine colostrum and/or probiotics — prevent or reduce exercise-associated gut disturbances.

The study results were published online recently in the journal Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics.

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Natural Health, Wellness

Wallpaper may contribute to sick building syndrome, a new study suggests.

Toxins from fungus growing on wallpaper can easily become airborne and pose an indoor health risk, the researchers said.

In laboratory tests, “we demonstrated that mycotoxins could be transferred from a moldy material to air, under conditions that may be encountered in buildings,” said study corresponding author Dr. Jean-Denis Bailly.

“Thus, mycotoxins can be inhaled and should be investigated as parameters of indoor air quality, especially in homes with visible fungal contamination,” added Bailly, a professor of food hygiene at the National Veterinary School of Toulouse, France.

Sick building syndrome is the term used when occupants start feeling ill related to time spent in a particular building. Usually, no specific illnessor cause can be identified, according to the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

For the study, the researchers simulated airflow over a piece of wallpaper contaminated with three species of fungus often found indoors.

“Most of the airborne toxins are likely to be located on fungal spores, but we also demonstrated that part of the toxic load was found on very small particles — dust or tiny fragments of wallpaper, that could be easily inhaled,” said Bailly.

Mycotoxins are better known for their occurrence in food. But “the presence of mycotoxins in indoors should be taken into consideration as an important parameter of air quality,” he said.

The study was published in Applied and Environmental Microbiology, a journal of the American Society for Microbiology.

Creating an increasingly energy-efficient home may aggravate the problem, Bailly and his colleagues said.

Such homes “are strongly isolated from the outside to save energy,” but various water-using appliances such as coffee makers “could lead to favorable conditions for fungal growth,” Bailly explained in a society news release.

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Anti Aging, Integrative Functional Wellness, Integrative Medicine

Eating fish at least twice a week may significantly reduce the pain and swelling associated with rheumatoid arthritis, a new study says.

Prior studies have shown a beneficial effect of fish oil supplements on rheumatoid arthritis symptoms, but less is known about the value of eating fish containing omega-3, the researchers said.

“We wanted to investigate whether eating fish as a whole food would have a similar kind of effect as the omega 3 fatty acid supplements,” said the study author, Dr. Sara Tedeschi, an associate physician of rheumatology, immunology and allergy at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Generally, the amount of omega 3 fatty acids in fish is lower than the doses that were given in the trials, she said.

Even so, as the 176 study participants increased the amount of fish they ate weekly, their disease activity score lowered, the observational study found.

In rheumatoid arthritis, the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks the joints, creating swelling and pain. It can also affect body systems, such as the cardiovascular or respiratory systems. The Arthritis Foundation estimates that about 1.5 million people in the United States have the disease, women far more often than men.

The new study, which was heavily female, draws attention to the link between diet and arthritic disease, a New York City specialist said.

“While this is not something that is new, per se, and it was a small trial, it does raise an interesting concept of what you eat is as important as the medications you take,” said Dr. Houman Danesh.

“A patient’s diet is something that should be addressed before medication is given,” added Danesh, director of integrative pain management at Mount Sinai Hospital.

When his patients with rheumatoid arthritis ask about diet, he said he often suggests they eat more fish for a few months to see if it will help.

“I encourage them to try it and decide for themselves,” he said, explaining that study results so far have been mixed.

In this case, the majority of study participants were taking medication to reduce inflammation, improve symptoms and prevent long-term joint damage.

Participants were enrolled in a study investigating risk factors for heart disease in rheumatoid arthritis patients. The researchers conducted a secondary study from that data, analyzing results of a food frequency questionnaire that assessed patients’ diet over the past year.

Consumption of fish was counted if it was cooked — broiled, steamed, or baked — or raw, including sashimi and sushi. Fried fish, shellfish and fish in mixed dishes, such as stir-fries, were not included.

Frequency of consumption was categorized as: never or less than once a month; once a month to less than once a week; once a week; and two or more times a week.

Almost 20 percent of participants ate fish less than once a month or never, while close to 18 percent consumed fish more than twice a week.

The most frequent fish eaters reported less pain and swelling compared to those who ate fish less than once a month, the study found.

Researchers can’t prove that the fish was responsible for the improvements. And they theorized that those who regularly consumed fish could have a healthier lifestyle overall, contributing to their lower disease activity score.

While they were unable to get specific data on information such as patients’ exercise, its benefits are proven, Tedeschi said.

She acknowledged that fish tends to be an expensive food to purchase. For those unable to afford fish several times a week, Danesh cited other options.

“In general, patients should eat whole, unprocessed foods,” he said. “If you can’t for whatever reason, an omega 3 pill is a second option.”

Because the study was not randomized, researchers were unable to make definite conclusions, but they were pleased with what they learned.

One finding that impressed Tedeschi “was that the absolute difference in the disease activity scores between the group that ate fish the most frequently and least frequently was the same percentage as what has been observed in trials of methotrexate, which is the standard of care medication for rheumatoid arthritis,” she said.

The findings were reported June 21 in Arthritis Care & Research.

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | UTEP (Local) RSS

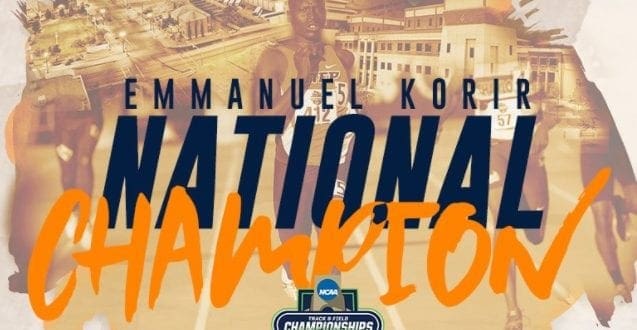

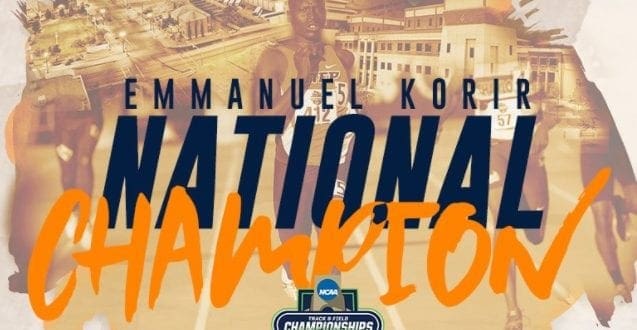

Emmanuel Korir has been named a semifinalist for college track and field’s highest individual honor, The Bowerman Award, the U.S. Track and Field and Cross Country Coaches Association (USTFCCCA) announced Thursday.

Korir wrapped up his freshman season with a sweep of both 800m national titles. The Kenyan is the first Miner to win the 800m NCAA title since Peter Lemashon outdoors in 1978, and the first to achieve the feat at both NCAA Indoors and Outdoors in the same year.

The All-American holds school records in the indoor 800m (1:46.75), the outdoor 800m (1:43.73) and the outdoor 400m (44.53). Korir is one of three athletes in the world to run a sub-45 400m and a sub-1:44 in the 800m.

Three finalists will be announced on Thursday, June 22 from the following list of semifinalists:

KeAndre Bates, junior, jumps, Florida

Edward Cheserek, senior, distance, Oregon

Christian Coleman, junior, sprints/jumps, Tennessee

Grant Holloway, freshman, hurdles/jumps, Florida

Fred Kerley, senior, springs, Texas A&M

Josh Kerr, sophomore, mid-distance, New Mexico

Emmanuel Korir, freshman, mid-distance, UTEP

Ioannis Kyriazis, junior, throws, Texas A&M

Filip Mihaljevic, junior, throws, Virginia

Lindon Victor, senior, combined events, Texas A&M

For more information on UTEP track and field, follow the Miners on Twitter (@UTEPTrack) and Instagram (uteptrack).

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | UTEP (Local) RSS

New UTEP Tennis Head Coach Ivan Fernandez announced his first two signees on Friday. Erandi Martinez Hernandez and Alisa Morozova will join the Miners for the 2017-18 season.

Martinez Hernandez graduated from Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education, a prestigious high school in Mexico City. She has been ranked among the top-five under-18 players in Mexico and has won three Grade 1 tournaments in both singles and doubles.

Hernandez reached the semifinals of the Masters Championship, a qualifier for a Women’s Tennis Association (WTA) Tournament in Mexico, and reached the quarterfinals at the Tampico International Tournament last August, where she faced several players that are now playing Division I tennis.

“I have been recruiting Erandi for a couple of months already,” Fernandez said. “I know that she’s got a lot of wins in Mexico against players that are now in Division I, so I have a really good idea of the level that she’s going to bring to the program. She’s very solid in singles and doubles and I think that she’s going to be a great addition to this team, especially having competed against a lot of collegiate players. She’s going to come in with a lot of international experience and she has been highly ranked in Mexico for her whole career. I definitely expect her to make an immediate impact in the lineup.”

Morozova recently graduated from the Gusev Secondary School in Russia, where she has been ranked among the top under-18 players the last three years. Morozova represented the Yaroslavi Regional Team as the No. 3 singles player and has won more than 10 Russian Federation Tournaments in singles and doubles.

“I spoke with Alisa’s sister a little bit and she told me that if she had been playing here in the U.S. she would have a UTR [Universal Tennis Rating] of 9 or 10, which is a very high level,” Fernandez said. “Her sister, who played for four years at St. John’s and just graduated, told me that she would probably play in the middle of the lineup at St. John’s, who just won their conference and went to the NCAA Tournament. Alisa is a very young player but she is very well-rounded. She’s also going to be capable of playing in the middle of the lineup here. We’re very fortunate that we were able to get her in so quickly and get her signed right away. She’s a very solid player, she’s going to mature and keep developing and both she and Erandi will definitely be in the lineup as true freshmen.”

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | UTEP (Local) RSS

UTEP claimed two superlative Conference USA track and field honors as Emmanuel Korir and Tobi Amusan were named C-USA Male and Female Track Athletes of the Year, announced by the league office on Friday afternoon.

“Both athletes are very special and talented. He [Korir] was the best candidate for our league and would most likely do very well other top conferences as well,” head coach Mika Laaksonen stated. “A lot of work goes into these things and Tobi worked incredibly hard over these past two years and she absolutely deserves this award, they both do.”

Korir ran a world best 1:14.97 in the 600m earlier this year at the New Mexico Cherry & Silver meet, which was his first race on an indoor 200m banked track. The freshman followed that up by capturing the NCAA title in the 800m (1:47.48) at the same track in Albuquerque, N.M., with a time of 1:47.48. The freshman is one of three athletes in the world to run an outdoor sub-45 400m and a sub-1:44 in the 800m.

The Kenyan native won the NCAA outdoor title in the 800m (1:45.03) and is the first Miner to win both titles in the same year.

Amusan was the leading scorer for the Miners with 25 points at the C-USA Indoor Championships and notched a meet record in the 60m hurdles with a time of 8.01. The sophomore helped her team win its third consecutive conference title. Amusan qualified to the NCAA Indoor Championships in the 60m hurdles where she notched a sixth-place showing.

The outdoor season started with a bang, as she set a school record (12.63) in the 100m hurdles at the UTEP Springtime meet. She followed that with a first-place finish at the 2017 Clyde Little Field Texas Relays in the 100m hurdles, setting a meet record time of 12.72. The Nigerian native scored 24.5 points at the C-USA Outdoor Championships leading the women’s team to its first ever outdoor conference title.

Both athletes were named semifinalists for college track and field’s high individual honor, The Bowerman Award. The women’s three finalists will be announced on Wednesday, June 21 and the men’s finalists will be announced Thursday, June 22.

For more information on UTEP track and field, follow the Miners on Twitter (@UTEPTrack) and on Instagram (uteptrack).

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | UTEP (Local) RSS

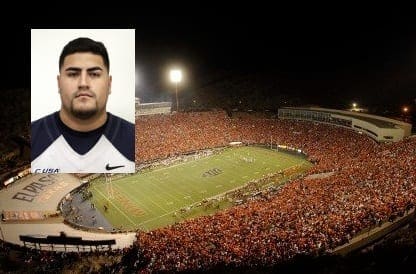

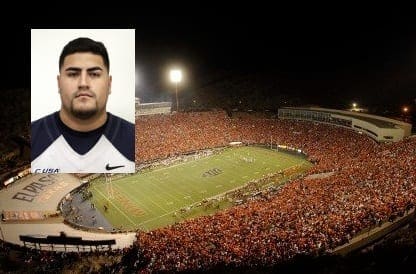

Offensive lineman Will Hernandez was named to the 2017 Athlon Sports Preseason All-American third team on Tuesday.

The senior comes back after a stellar season where he garnered AP All-American second team, FOX Sports’ All-American second team, All-Conference USA first team and Pro Football Focus Best Pass Protector honors. The lineman has started all 37 games in his career for the Miners at the left guard position.

He led the offensive line that paved the way for Aaron Jones to rush for a single-season program-record 1,773 yards, while Jones also became UTEP’s all-time leading rusher last season. The Miners averaged 185.5 rushing yards per game and scored 20 touchdowns on the ground.

Hernandez is one of two student-athletes from C-USA that makes an appearance on the Athlon Sports All-American team. The Las Vegas, Nev., native also was named to the Athlon Sports Preseason All-C-USA first team.

Teammate Alvin Jones also garnered Athlon Sports All-C-USA first team recognition, while Devin Cockrell and Terry Juniel received second team honors. Jones was appointed to the 2016 All-C-USA second team after leading team in tackles 93 (44 solo). He ranked fourth in the league in tackles per game (9.3) and added 6.0 tackles for loss (28 yards), 2.5 sacks (22 yards) and a pass breakup.

Cockrell started all 12 games last season and ranked fourth on defense, while leading all defensive backs with 58 tackles (31 solo). He added 3.0 tackles for loss, a pass breakup, a quarterback hurry and a fumble recovery. The senior led team with 10 special team’s tackles (seven punt return tackles)

Juniel returns to the Miners special teams unit as the starting punt returner. The specialist was the team’s leading punt returner, tallying 203 yards on 22 returns (9.2 avg.), with a pair of long returns of 43 yards. Juniel led C-USA in punt returns and return yards. The junior returned nine kickoffs for 164 yards (18.2 avg.) with a long of 26 yards.

UTEP’s center Derron Gatewood and punter Alan Luna also received recognition on the All-C-USA Preseason fourth team.