by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Functional Medicine, Gut and Intestinal Health, Health, Wellness

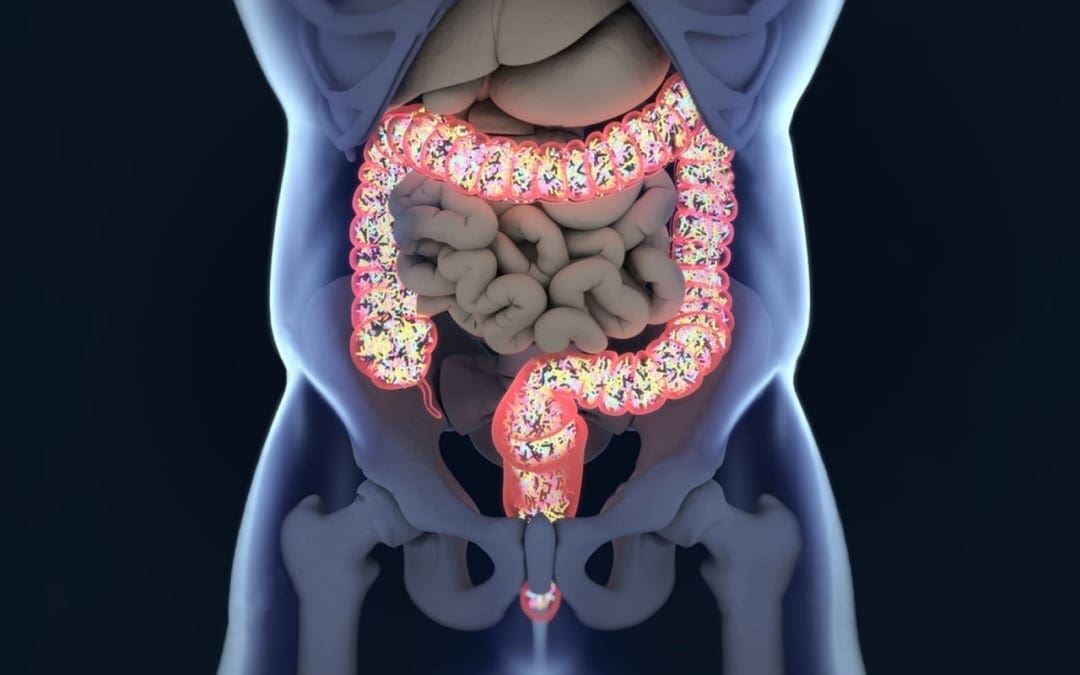

In the last article, we talked about how the microbiomes in our body worked and functioned. As well as learning what each microbe does in our bodies but mostly in our gut. When we are learning more and more about the microbiome, we discover many exciting things that our bodies are capable of as well as being the workers in our intricate immune system. In today�s article, we will be taking a look at what polyphenols does to our microbiomes as well as specific vitamins that are very helpful to our gut and going in-depth more with SCFAs (Short Chain Fatty Acids) and the Tight Junction.

The Role of Polyphenols in Microbiome Balance

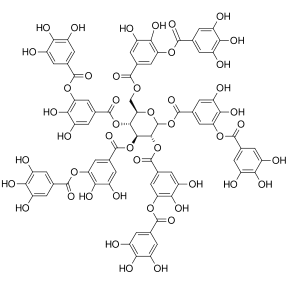

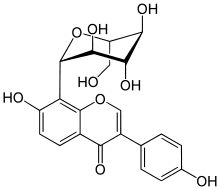

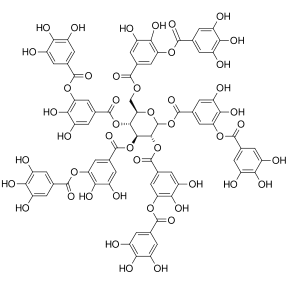

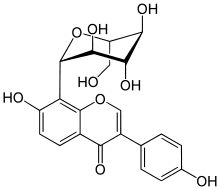

Polyphenols, or phenolic compounds, are considered a type of micronutrients, and they are plentiful in plants. They have been well-studied for their role in the prevention of chronic diseases such as CVD, cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases. They also have antioxidant properties, and there are several hundreds of polyphenols that are found in edible plants that serve a giant purpose of defending our bodies against ultraviolet radiation or aggression by pathogens.

To figure this out, think of it like this: The bacteria in our large intestine releases polyphenols from the plants we eat in our diets. It is then transformed into a diet composition that alters the bacterial ecosystem (through the prebiotic effects and antimicrobial properties) to make our gut happy.

Here are some of the microbes that are in polyphenols:

- Phenolic acids: These are derivatives of benzoic acid and derivatives of cinnamic acid.

- Flavonoids: These microbes contain flavonols (e.g., quercetin), flavones, isoflavones (e.g., phytoestrogens), flavanones, anthocyanidins, and flavanols (e.g., catechins and proanthocyanidins)

- Stilbenes: These microbes are resveratrol

- Lignans: these are minor in the human diet and are linseed oil

Surprisingly some factors affect the polyphenol content of plants, and these include:

- The ripeness at the time of harvest

- The environmental factors (exposure to light, soil nutrients, pesticides)

- processing and storage

When we eat organic fruits and vegetables, they have more polyphenol content that is usually, due to growing under slightly more stressed conditions. Which requires the plant to generate a stronger �defense and healing� response to the environment, and only 5�10% of the total polyphenol intake is absorbed in the small intestine. And 90-95% polyphenols that are linked to fibrous components must be liberated through hydrolysis by bacteria in the large intestine.

Surprisingly some polyphenols do not show up in plasma in humans after ingestion, and a large quantity is metabolized by intestinal bacteria or used to neutralize various pro-oxidizing agents in the intestinal lumen.

Clostridium and Eubacterium (which are both Firmicutes), are the primary metabolizers of polyphenols. Studies theorized that higher polyphenol intake may play a role in shaping the Bacteroidetes to Firmicutes ratio (e.g., inflammatory response potential, obesity, etc.) and can be harmful to our bodies.

However, more recent studies have shown effects of inhibition on Clostridium and Staphylococcus of polyphenols such as grape seed extract, in favor of Lactobacillus and other studies have demonstrated potent inhibition of phenolic compounds thymol (thyme) and carvacrol (oregano) on Escherichia, Clostridia and other pathogens, while simultaneously leaving Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria have been unaffected.

Here are some other examples of some polyphenols:

- Resveratrol increases Clostridia, Lactobacillus, and Bifidobacteria

- Blueberry phenolics increase Bifidobacteria

- Phenolic compounds in tea suppress C difficile and C perfringens

- Catechins (found in high doses in teas and chocolate) act on different bacterial species (E. coli, Bordetella bronchiseptica, Serratia marcescens, Klebsiella pneumonia, Salmonella cholestasis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and Bacillus subtilis) by generating hydrogen peroxide and by altering the permeability of the microbial membrane

- Some studies have shown that polyphenols can interfere with bacterial cell signaling and quorum sensing (environmental sampling)

- Polyphenols can also cause bacterial populations to stop expansion through signaling interference

- Some research indicates certain polyphenols may be able to block the production of bacterial toxins (H. pylori and tea/wine polyphenols)

The Applications for A Diet

When it comes to eating a healthy diet, variety does matter. The colors, the types of fibers each organic food has, and whether you are going to do it daily or weekly. When you are trying to be in a healthy lifestyle, it always starts with the food. When you are looking for fresh produce, try to emphasize fresh, organic, and minimally processed versions of polyphenol-rich foods. However, don�t boil produce. Instead, try steaming then, and it is the best, but roasting or light frying is not only better, but it tastes so good.

Vitamins that help our Microbiome

When we are older, we tend to lose specific vitamins that actually helps us and our bodies to be healthier. Here are some of the vitamins that are really good for our gut and can help us prevent leaky gut.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D controls the development of gut-associated lymphoid tissue in our bodies. It is trafficking between gut dendritic cells, and they can differentiation of T-regs and T-reg function in our gut. But the expression of VDR, which influences IL (interleukin) production and tight junction integrity to help our gut.

When it comes to our gut, here are some of the effects of Vitamin D on the gut microbiome. The higher the Vitamin D levels are, they will allow commensal bacteria to secrete more AMPs (antimicrobial peptides). When patients take a high dose of Vitamin D, over 5 weeks can lead to a significant reduction in Pseudomonas spp and Shigella/Escherichia spp in upper gut intestines.

Another thing that Vitamin D does is that it can increase T cell differentiation in the colon. A lack of T-regs increased the incidence of asthma, allergies, autoimmune, and autism. But T-regs can prevent the development of aberrant immune responses such as autoimmune and food sensitivities. We here at Injury Medical Clinic, talk about functional medicine to our patients and try to help them recover from their ailments.

Because Vitamin D exposure fluctuates seasonally for many individuals, it has been observed that lower Vitamin D levels in the winter tend to lead to changes in the intestinal microbial balance. This will make our bodies have a decreased level of Bacteroidetes and an increased level of Firmicutes. This is the reason for �winter weight gain� in many individuals as F: B ratio changes.

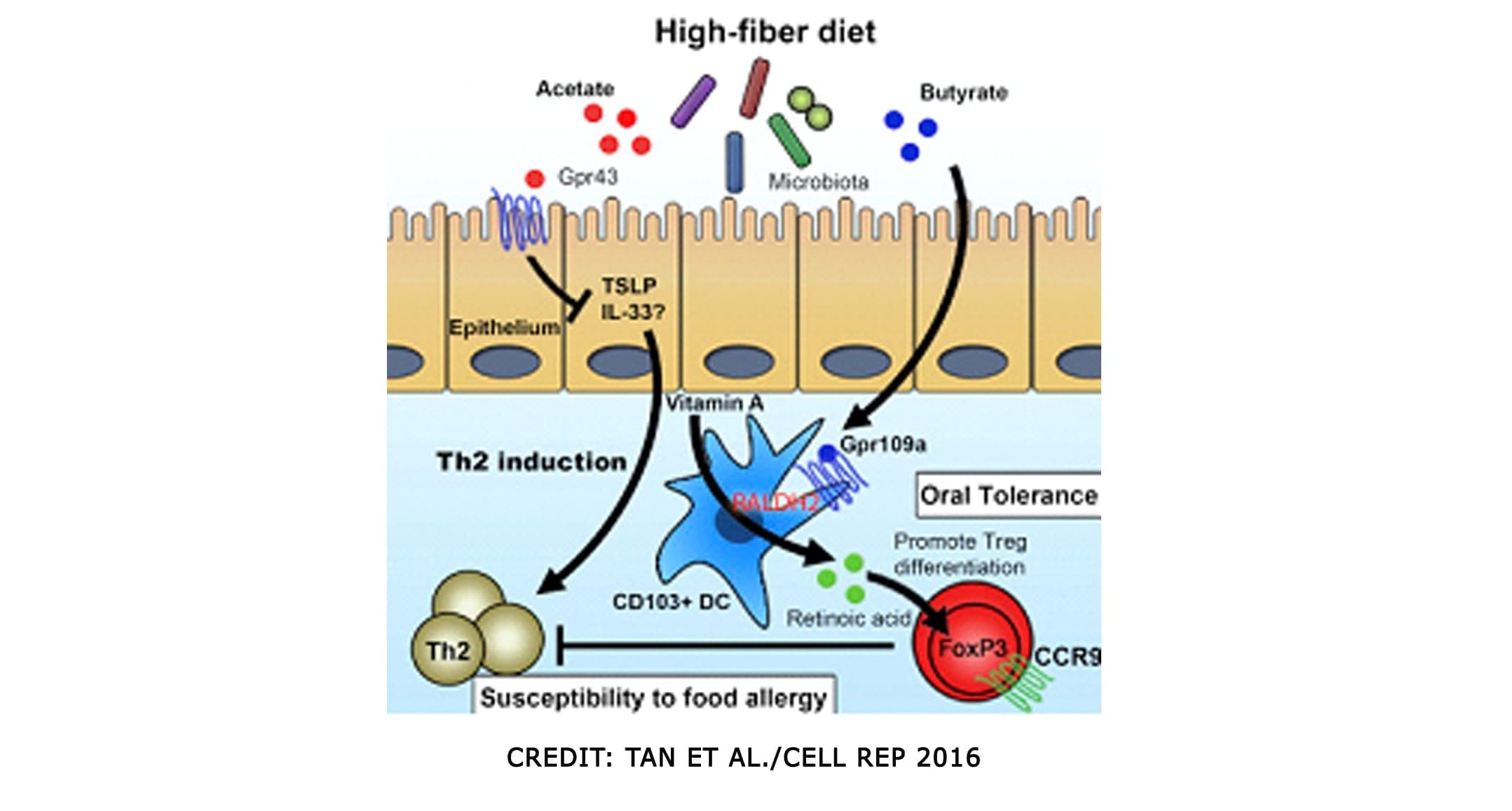

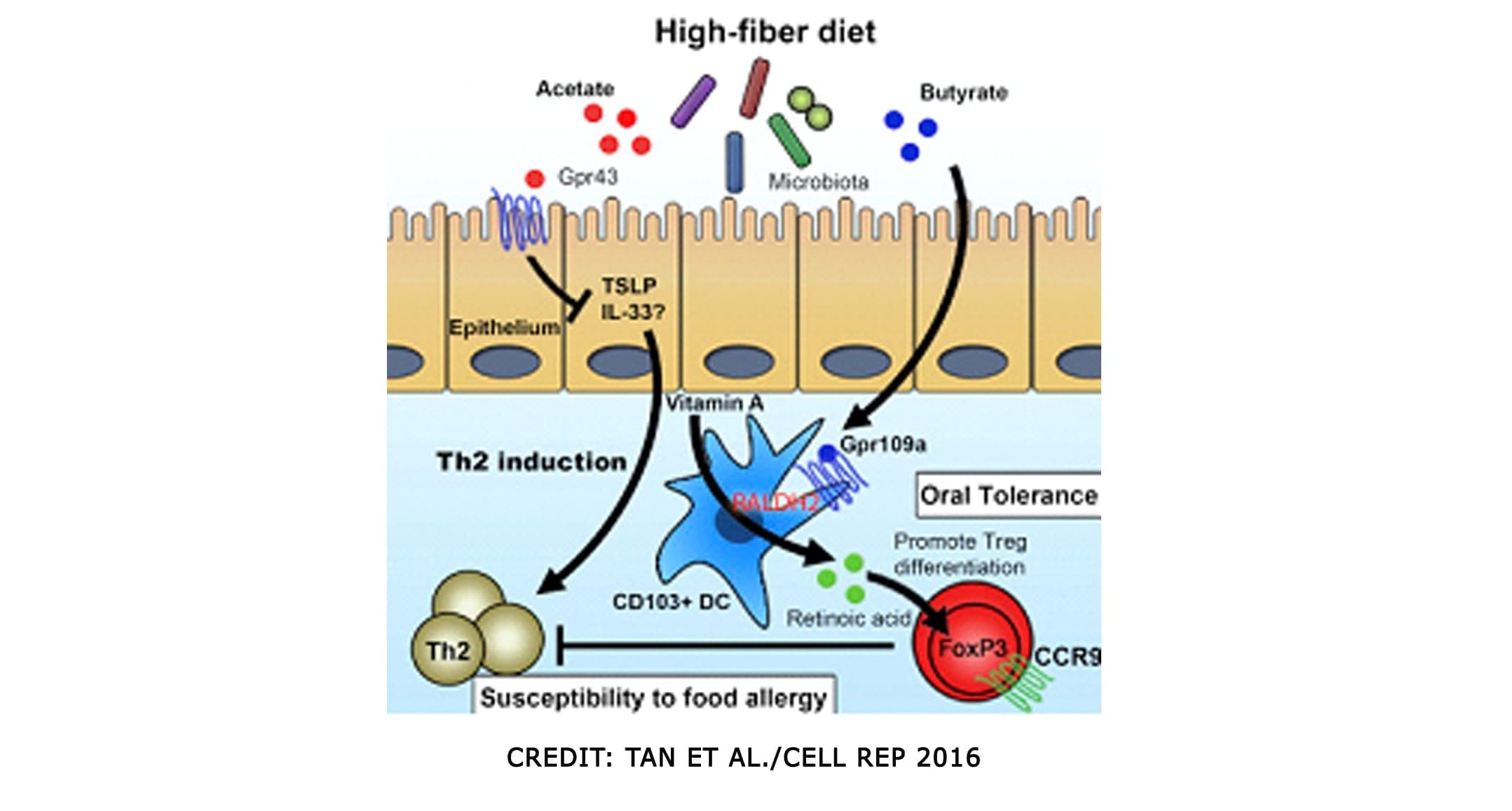

Vitamin A

This is a retinoic acid that is required by dendritic cells (DCs) to induce T-cells (and B cells) which are the �tracking and regulation system� of the mucosal immune response. Because of this, T-cells must differentiate into T-regs to maintain a �calm and cool� system or immune tolerance to both our environment, symbiotic organisms, and food.

Omega-3 Fatty Acids

We talked about Omega-3s in a previous article as they are one of the many supplements that we can�t produce in our bodies. It can be mostly found in fish, and some plants can contain omega-3s. But it is a vital team player when we are trying to be healthy and can prevent a leaky gut. Not only that but omega-3s are crucial importance to more youthful skin.

SCFAs (Short Chained Fatty Acids)

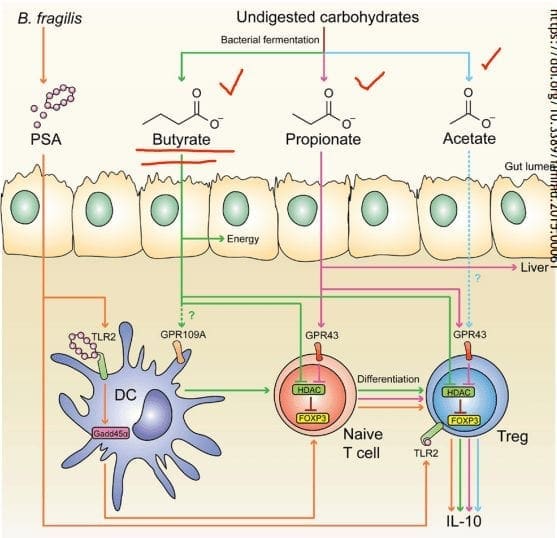

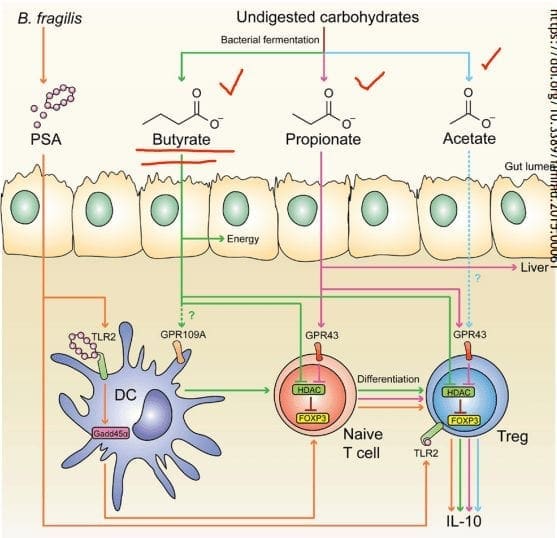

SCFAs (Short Chained Fatty Acids)�are well-studied to demonstrate anti-inflammatory properties in the large intestine. They are the primary source of fuel for cells lining the intestinal epithelium of the large intestine. They contained: �Butyrate, Proprionate, Acetate. In a previous article, we discussed what SCFAs do when we eat fatty food. It can be both good or bad, depending on what kinds of food you consume. SCFAs act on G-protein coupled receptors to induce differentiation of T-cells, but also on those GPRs in DCs. They can both be direct and indirect influences on our gut.

SCFAs can produce bacteria and can directly impact T-reg production. And that SCFAs inhibit the mucosa and competitively inhibit opportunists. Some foods that provide higher resistant starch will typically yield the most short-chain fatty acids upon microbial fermentation

Tight Junction Modulations

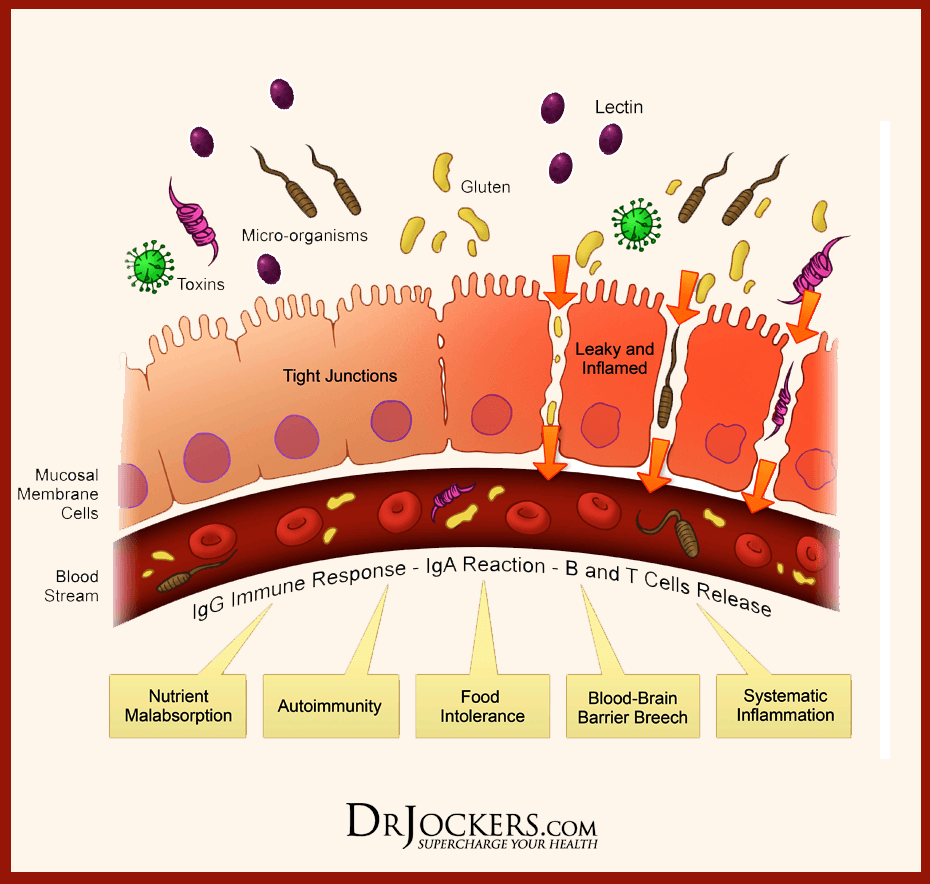

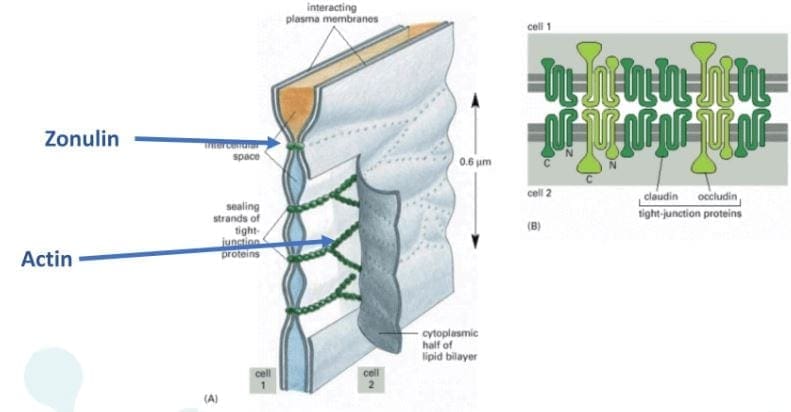

The tight junctions are the gateways between the epithelial cells. In a previous article, we took a look at what the tight junction is. They control the flow of nutrients, macromolecules, and other substances that are usually allowed to pass through without cellular diffusion or absorption.

Conclusion

All in all, we covered a lot of information about what polyphenols does as well as specific vitamins and supplements that can help our bodies prevent a leaky gut. The microbiomes in our collection and the use of functional medicine can be beneficial in helping us not only to a better, healthier life but, a working, functional body for us when we are older. Tomorrow we will end this three-part series with foods and tips to have a healthy microbiome in our gut and our bodies.

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Functional Medicine, Gut and Intestinal Health, Wellness

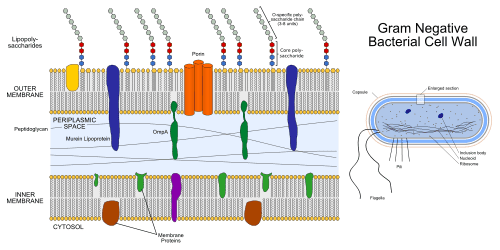

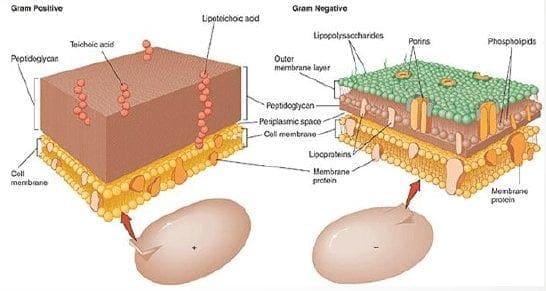

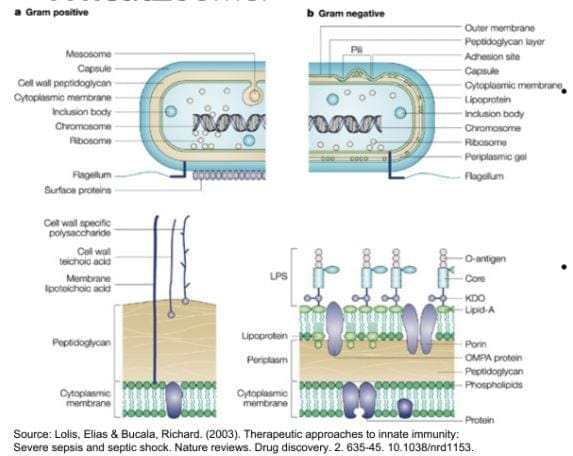

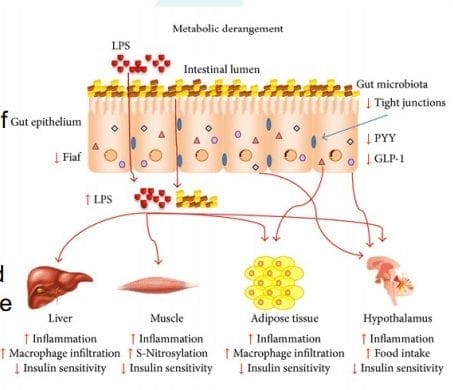

To understand exactly how lipopolysaccharides and gram-negative bugs affect the immune system we must first investigate what lipopolysaccharides are and their role in gram-negative bacteria and the human body as a whole.

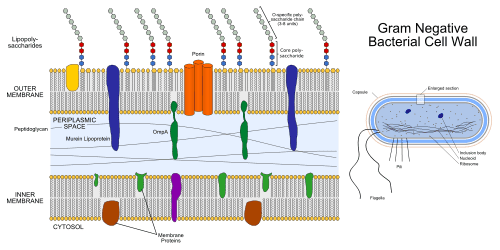

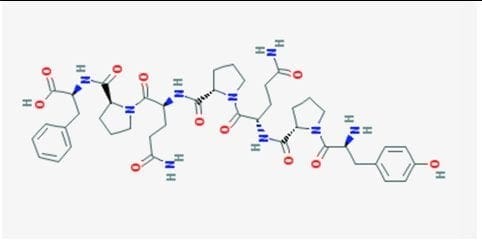

LPS (Lipopolysaccharides)

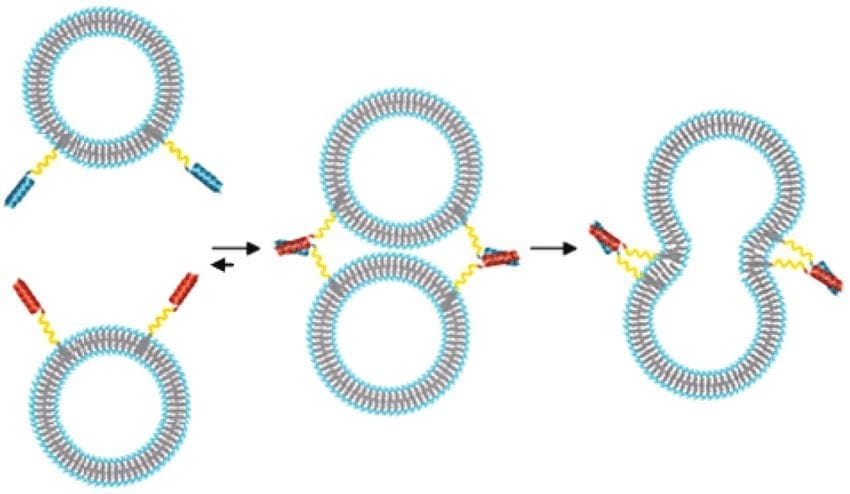

Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) are large molecules consisting of a lipid (fatty acid) and a polysaccharide composed of the O-antigen, outer core, and the inner core all joined by covalent bonds. �Lipid A in LPS is the hydrophobic component responsible for the major bioactivity of LPS. Hydrophilic polysaccharides consist of long chains of monosaccharides (simple sugars) linked together by glycosidic linkages. LPS play their role in the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria by supporting the structure of the bacteria and shielding the membrane from chemical attack. Gram-negative bacteria are related to foodborne diseases, respiratory infections, plagues, and some sexually transmitted diseases. Some gram-negative bacteria have become so resistant to antibiotic drugs that they are often very difficult to treat and unfortunately vaccines are not available for these types of bacterial infections. Additional enzymes can sometimes alter the structure of the LPS, and though the structure is not required for the bacteria�s survival it is closely related to the virulence of bacteria. For example, the lipid A component of LPS can cause toxic reactions when lysed by immune cells. LPS in humans trigger the immune system to produce cytokines (hormone regulators). Production of cytokines is a common cause of inflammation.

Now that we are able to recognize the relationship between LPS, gram-negative bacteria, and inflammation/infections in the human body, we must understand how to prevent and treat infections related to gram-negative bacteria. Gram-negative bacterial infections are caused by contact between infected and non-infected peoples. They are very common in healthcare settings, but by taking simple measures such as hand washing and keeping a strong immune system will help prevent them. How do we keep a strong immune system? Choosing a healthy lifestyle is the first most basic step in this process. Because the immune system is a system, we must understand that there is no direct way to improve its strength. It is strengthened through what we put into our body and how we treat our body. However, it is important to distinguish between building a strong immune system and boosting the number of immune cells in our body. It is potentially harmful to boost the number of immune cells because there are so many different kinds of cells in the immune system that respond to so many different microbes in so many ways. Diet, exercise, reducing stress levels, and some herbs and supplements all contribute to building and supporting a strong immune system.

Conclusion

Throughout this article, we have learned about lipopolysaccharides and the role they play in gram-negative bacteria. Gram-negative bacteria are known to be harmful to the human body so we have found ways to prevent the harmful infections it causes. The immune system plays an obviously important role in fighting infections, but it needs to be strong to support our body and fight infections efficiently. This basic knowledge is provided to set the basis for further research on how to support the immune system.

Resources:

https://www.niaid.nih.gov/research/gram-negative-bacteria

https://www.scbi.nih.gov/pubmed/20593260

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/gram-negative_bacteria

https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/how-to-boost-your-immune-system

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Functional Medicine, Gut and Intestinal Health, Wellness

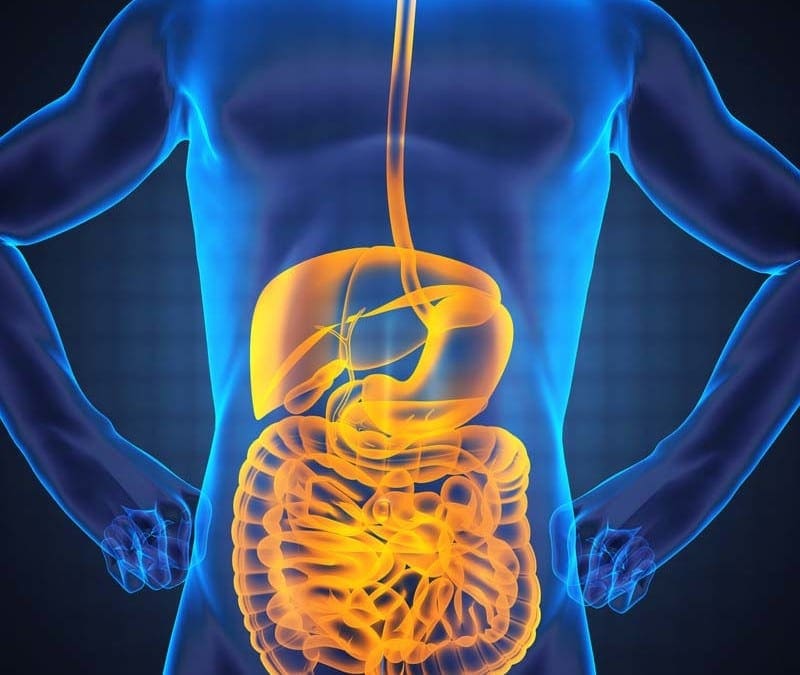

The microbiomes in our bodies are fascinating. They help our various organs function correctly, helping out our immune systems battle terrible stuff. They can tell us what we are doing to our bodies when we consume food. However, the microbiomes in our gut tell us a different story as we are going to discuss what does microbiomes do as it functions in our body as well as our gut.

The relationship between the gut microbiota and its host plays a crucial role in:

- immune system maturation

- food digestion

- drug metabolism

- detoxification

- vitamin production

- prevention of pathogenic bacterial adhesion

Also, the composition of the microbiota is influenced by environmental factors such as diet, antibiotic therapy, and environmental exposure to microorganisms.

Why Don�t We All Have the Same Microbiome?

Whenever we are trying to live a healthy lifestyle, our bodies will go through so many changes. When we get rid of the bad stuff that is causing us problems and the beautiful thing start taking effect in what we put in our bodies. We, as humans, have different body structures and body types that are way different. Some people lose or gain weight differently. When other people exercises, they go at their own pace, and several factors influence the bacterial composition in taxa type and abundance. These factors include:

- host phenotype, such as age, gender, body mass index (BMI)

- lifestyle

- immune function

- geographical belonging and environmental factors

- use of antibiotics, drugs, and probiotics

- DIET

Moreover, long-term dietary habits have been shown to play a crucial role in creating an inter-individual variation in microbiota composition.

Manipulating the Microbiome: Key Terms

Here are some key terms to remember when we are talking about the microbiome.

- Stability: resistance to change and the ability to maintain homeostasis.

- Resilience: capacity to return to homeostasis after disturbance.

- Diversity: DIVERSE microbiomes are more stable and more resilient (to antibiotics); more resistant to foreign invasion (pathogens).

- Relative Abundance: Even �good� bacteria can be too abundant without balance from symbiotic species; the presence of �bad� bacteria is not necessarily always harmful if enough �good� are there to balance.

- Colonization Resistance: The capacity of the microbiome communities to resist new colonization by pathogens and other transients.

- This is a KEY factor for preventing GI infections; but also explains why probiotics are not always practical.

- Our COMMENSAL microbiome is our first line and of defense

- Microbial depletion: Infection; Antibiotics; Toxins/Chemicals; Stress

- Restore balance/� reseeding�: (the term �reinoculate� is not really correct) Probiotics; Fermented foods; Prebiotics/Polyphenols.

Advantages to DNA Testing

For many practitioners, measuring microorganism DNA allows for:

- Detection of a more diverse collection of microorganisms, (more genus and species, particularly anaerobic species)

- They can measure at the species and subspecies level

- They have a much better snapshot of dysbiosis and diversity

- Have better accuracy of results

- Much faster turnaround time and much less expensive

- Concept of �epigenetics.�

However, DNA is DNA-dead or alive whenever practitioners are looking at a patient�s DNA structure. Culture Technology is still considered �gold standard� but has several limitations. They are trying to culture anaerobic bacteria, but some of the most important bacteria are anaerobic commensals. There is a limited detection of several microorganisms, but it�s usually genus level only. Microorganisms can grow and/or die in transit and what�s measured in the culture dish is not always 100% indicative of the sample at the time of collection; the environment can morph while in transit to the lab and changes in pH etc.

Important Groups

These are some of the microbiomes that are very functional to our bodies and what parts do they play.

Commensals

This microbiome provides the host with essential nutrients and contains Aerobic and Anaerobic microbiomes.

- Aerobic (survives better in oxygenated environments; less prevalent in the colon, however, some are considered �obligate anaerobes�). They are:

- Lactobacillus

- Bifidobacterium

- Bacillus

- Anaerobic (more likely to be found colonizing the distal colon due to limited oxygen). They are:

Lactobacillus and Bifidobacteria

These two are the most well-researched genus of bacteria. They are widely available in commercially available probiotic products.

- Lactobacillus are:

- lactic-acid forming bacteria

- Form biofilms which allow surviving harsh/low pH conditions (stomach acid)

- Helps maintain the integrity of the intestinal barrier

- Abundant in probiotics/fermented foods

- Bifidobacteria are:

- One of the first bacteria to colonize the gut after birth

- Aids in digestion, reducing inflammation, and stimulation of immune cells

Bacillus

These are spore-forming bacteria. They form spores in harsh environments which makes them more resilient, heat-stable, and have better viability in the gastric environment. But they may have better efficacy as probiotic therapy in SIBO population. These are in another category of commercially-produced probiotics beyond the standard Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium.

In the health world, known as �Soil Based Probiotics.� They are very prominent in the environment and their primary role in immunomodulation; stimulation of the immune system. They are a production of GALT-Gut Associated Lymphoid Tissue and are known to be significant players in the production of B Vitamins and Vitamin K2 in the gut known as Bacillus subtilis

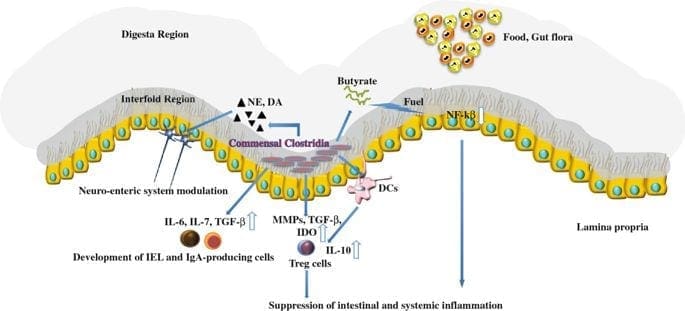

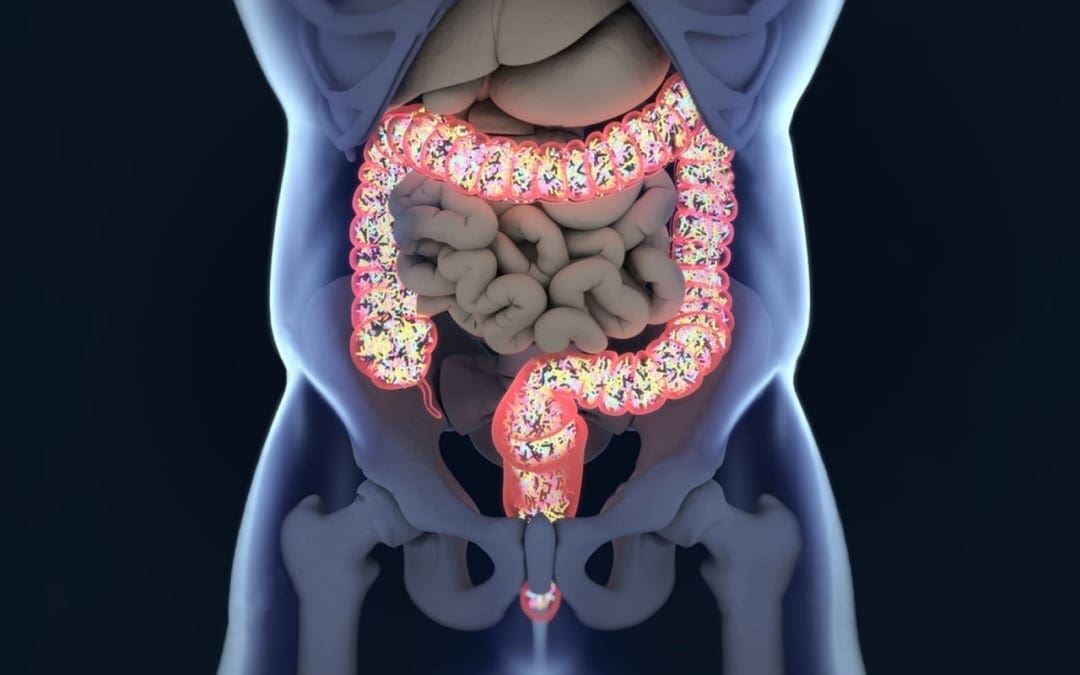

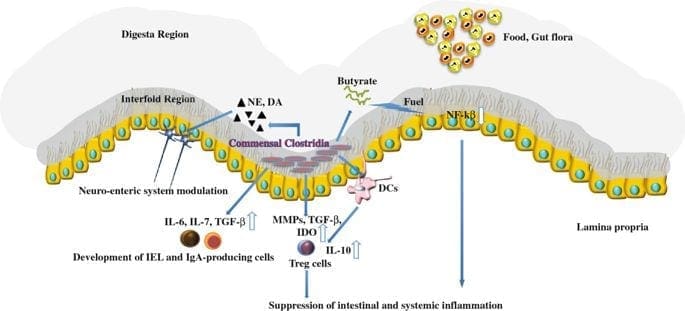

Clostridia

These are a major anaerobic group of commensals. They comprise 10% to >50% of the microbiome and are critical for the health of the gut barrier and intestinal lining, and barrier integrity. These are essential producers of butyrate (SCFA) and secondary bile acids. They also thrive on a high and diverse fiber diet, grape, and red wine polyphenols such as Blautia, Butyrivibrio, Eubacterium, Faecalibacterium prausnitizi, Roseburia, Ruminococcus, etc. However, there are usually no probiotic supplements to directly increase the abundance of clostridia.

Akkermansia

These microbiomes make up 1-3% of a healthy microbiome, and they help maintain the health and integrity of the mucosal barrier.

- Akkermansia muciniphila = mucin lover

They also help with reducing inflammation and may impart protection of inflammatory bowel diseases. These microbiomes are keystone species that are highly correlated with higher microbiome diversity.

Proteobacteria

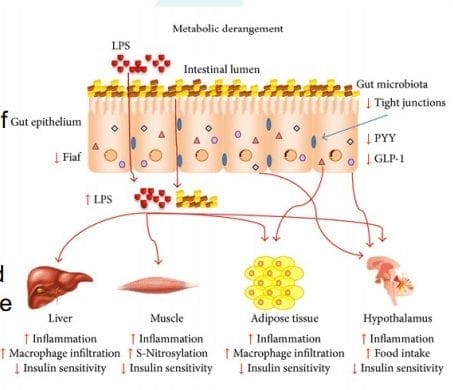

This is a PHYLUM category of bacteria. This microbiome contains gram-negative and all bacteria that carries an LPS. This group includes plenty of beneficial bacteria but also contains several pathogens that tend to thrive in pro-inflammatory condition.

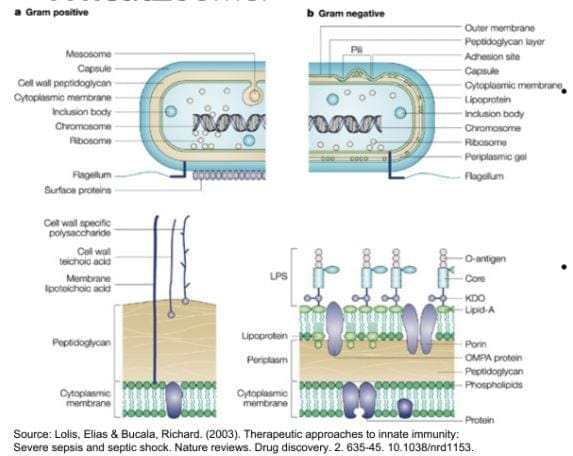

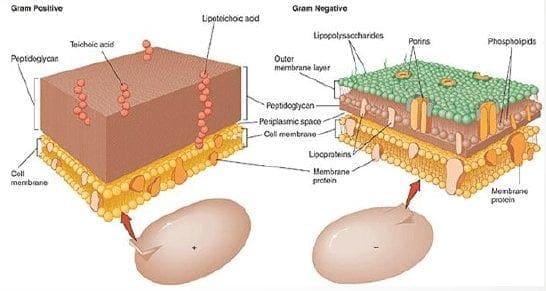

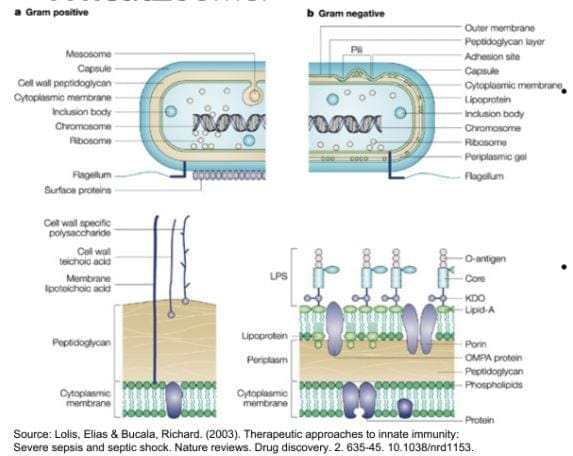

Gram (+) vs Gram (-) Bacteria

These two types of bacteria are in our bodies as they have very different functions that can either protect or disrupt our gut.

- Gram-Positive (+) contains:

- Peptidoglycan

- Lipoteichoic acid

- Gram-Negative (-) contains:

- LPS as a component of their cell wall

- LPS is a very powerful ENDOTOXIN- a known contributor to induce significant inflammation and potent immune response

- LPS antibodies are measured on Vibrant Wellness Wheat Zoomer/Intestinal Permeability Panel

However we can�t generalize Gram (-) as �bad� or Gram (+) as �good� or vice-versa, but we can control it with the Zoomers test.

LPS(Lipopolysaccharide)

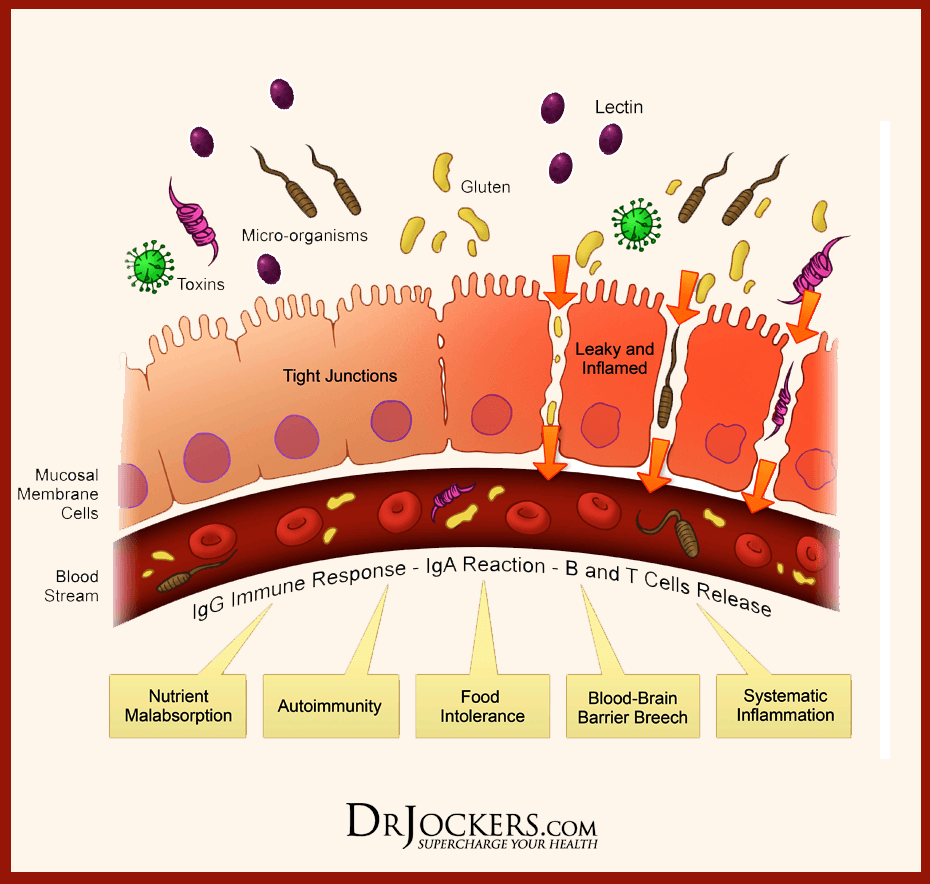

In the last article, we mentioned them briefly, but here is a refresher on what theses microbes do. They are a fat/sugar molecule that lines the gram-negative bacteria inside the gut, and they protect those bacteria from bile salts. They are present inside the gut lumen under normal physiological conditions, and they usually should not enter the bloodstream. But if it does open in the blood then�

- 1) LPS antibodies are created-tagged as �non-self.�

- 2) Indication of intestinal permeability.

- 3) triggers multiple inflammatory cascades = ENDOTOXEMIA

- 4) Can help differentiate if leaky gut is happening between cells or through cells (or both), which are Transcellular vs. Paracellular pathways

Conclusion

These are the microbiomes that are in our body and how each of them plays a role to make our bodies healthy. We here at Injury Medical Clinic, do talk with our patients about what goes on in their bodies. We inform them on how to take care of themselves through the means of functional medicine. This is part one of a three-part series since tomorrow we will be discussing the roles of polyphenols in the Microbiome balance.

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Functional Medicine, Gut and Intestinal Health, Health, Wellness

In the last three articles, we introduced the wheat zoomer, went in-depth about the intestinal permeability, and the microbes in our gut. We also talked about the hidden problem with gluten as well. Today we will be discussing what to do after your patient comes in for a check-up after completing their gut healing process. For this to work, patients have to be gluten-free for the results to work. After the healing phase, local chiropractors, health coaches, and physicians can introduce gluten back slowly into the patient’s diet.

Checkups

When the patient comes in for a check-up, here are some of the things doctors look for:

- If everything is green, re-introducing gluten may be possible for patients.

- If anything is still yellow or red, patients must continue to avoid gluten and keep the gut healing process until the test results are all green.

After the appointment, patients can retest the wheat zoomer in about 3-9 months. However, there are about 50% of individuals with celiac disease that may also have antibodies to casein and may have to go dairy-free to heal their gut. Although some individuals are gluten sensitive may not be lactose intolerant but can go dairy free if they want to.

Lectins

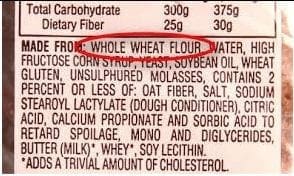

Surprisingly all plants have lectin, but some of them are not problematic to humans thankfully. Legumes and grains play a role in increasing the diversity of microbes that may be beneficial or harmful to our bodies. Wheat Germ Agglutinin is the only specific lectin to the Wheat Zoomer, but it doesn�t reflect the overall lectin sensitivity but, consider the lectin zoomer to determine any particular lectins that your patient is sensitive to without eliminating unnecessary foods that are beneficial to the gut healing process.

Soy

Many studies show that soy may be a problem due to the saponin since it does have higher lectin count. Here at Injury Medical clinic, we suggest that running the Lectin Zoomer on our patients with intestinal permeability makes sense for them to heal correctly. But animal studies stated that soybean agglutinin has the effect of the increasing release of zonulin away from the TJ (tight junction). And a human study reported that if the soy saponin is poorly absorbed or utilized by the human intestinal epithelial cell will end up metabolizing the intestinal bacteria and cause more harm to human.

Surfactants

Known as sucrose monoester fatty acids is mostly used in cosmetics, food preservatives, food additives. Sucrose esters are used as a surface treatment on some fruits like peaches, pears, cherries, apples, and bananas. It keeps the moisture on the peel or rind controlled. Sucrose mono ester used in cosmetics as an emulsifier.

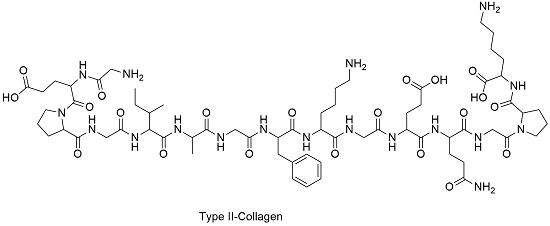

Bone broth/Collagen

Up to this date, there are minimal studies that have examined the role of bone broth or collagen that it repairs the intestinal barrier. It all depends on the animal and the bone it comes from and the contents that people have put in a bone broth soup.

However, there is a small body of evidence for the use of collagen peptides seem to support the usage in their autoimmune disease treatment protocol. But the results cant be extrapolated whether bone broth would have similar effects. So more studying about bone broth is needed.

Organic Produce

When people say that they are going organic, it is beneficial for people that are willing to change to a healthy lifestyle. Granted that organically produces are locally grown, but still, organic produce or non-organic produce will not have less or safer pesticides. They are different, but all of the crops like fruits and vegetables are grown with pesticides.

Just like all fruits and vegetables, still, wash them thoroughly to reduce the number of pesticides and surfactants exposure and enjoy them to your heart’s content.

Resistant Starches

Resistant starch foods are a form of carbohydrates that can be converted to short fatty acids by SCFA-producing bacteria. With higher SCFA levels, these starches aid immune tolerance, T-cell differentiation, and intestinal barrier homeostasis. Other types of fibers are high value, and variety is essential. Like for example, cooked/cooled rice and potatoes are excellent resistance starch foods.

“Eat like a vegetarian who eats meat.”- Dr. Alex Jimenez�D.C., C.C.S.T.

Polyphenol Foods

Polyphenols, flavonoids and other phenolic compounds will aid to maintained TJ stability through inhibiting phosphorylation of TJ complexes.

Fermented Foods

Fermented food or drinks that contain live probiotic cultures are excellent in promoting a healthy gut. However, it is challenging to study fermented food and beverages due to highly variable stains, composition, nutrient content. But studies found that participants who drink a fermented plant extract drink saw improvements in their body and increased total antioxidants and total phenolic in plasma as well as with reducing total C and LDL-C.

Beneficial bacteria like Bifido and Lactobacillus were increased while E Coli and C perfringens were decreased in the gut. So drinking or eating fermented food can help our gut and help our bile growth to be flushed out.

Granted, we all know that trying to be healthy is very hard. It is true that even though exercising is easy because we can do it over and over again until we are masters at it but, when we overdo the exercises it will cause harm to our bodies and hurting it in the process. �Eating healthy is hard as well because our bodies may have a food allergen or a food sensitivity that will make us disappointed that we can�t enjoy the foods we want to eat. Yes, eliminating diets are very hard and challenging to follow in the long term and have poor compliances when we don�t put in the work. So start by exploring other tests to tailor patients diets to meet their health needs and prolong their recovery period.

Supplements

Supplements are fantastic to aid the valuable nutrients and minerals our bodies can�t produce. Common supplements prescribed include:

- L-glutamine

- Vitamin D3

- Collagen

- Colostrum

- Zinc carnosine

- Ox bile

- Omega-3s

- Turmeric/Quercetin

- Magnesium

Stress Management

Granted that stress is part of our lives and we can manage small amounts of it, and it is beneficial to us, but some people have chronic stress and have to go to a doctor to get it treated. But there is hope as there are ways to manage stress and doing it functionally and naturally.

Conclusion

So all in all, just to recap, if your patient is good to go and their test results are all green, you can introduce gluten back to their diets again in small increments and can be rested in about 3 to 9 months. But if your patient does have a gluten allergen then just let them know that they must continue to be gluten-free. We here at Injury Medical Clinic, always put our patient�s needs first for them to live their best lives with functional natural medicine.

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Functional Medicine, Gut and Intestinal Health, Health, Wellness

With the last article, we talk about how our gut system actually works. With the many microbes that inhabit our intestines, we do try to our best to lead a healthier lifestyle. Here at Injury Medical, local chiropractors and health coaches inform our patients about functional medicine as well as helping them to prevent a leaky gut. Here we will talk more about what the microbiomes in our intestines do when we are exposed to harsh environments.

The Microbiome

The significant role of the microbiome in the epithelial barrier integrity and breakdown. However, we can�t have a conversation with patients about intestinal permeability and food sensitivities without telling them about the role the microbiome plays.

The Wheat zoomer is rich with data but adds the Gut zoomer with the patients; the results are more accurate.

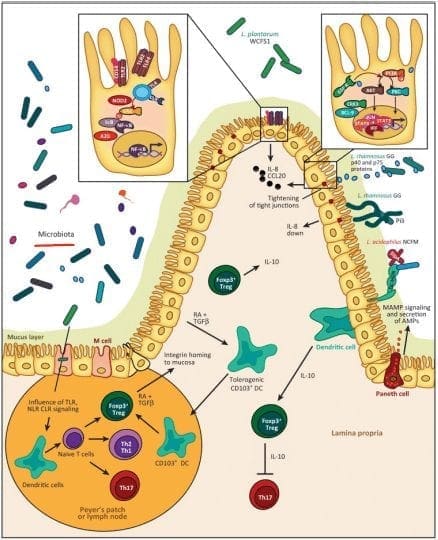

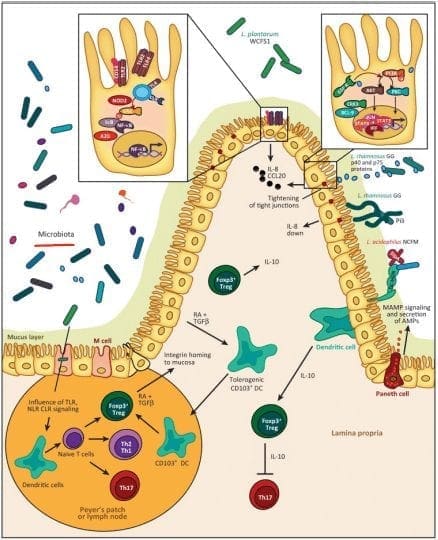

Microbial Influence on our Intestines

- Immune influence: One of the leading roles that microbiomes play in the immune system is that it generates byproducts of carbohydrates/fiber fermentation that will influence T-cell differentiation. Without the distinction, we will see an increase of being at high risk of autoimmune diseases, allergies, autism, and asthma.

- SCFAs (Short Chain Fatty Acids): The food we consume gets fermented for good bacteria to feed on. SCFAs creates fermented fibers by commensal microbes into Butyrate, Propionate, Acetate. These three are essential to the intestinal immune system. These SCFAs can influence T-cells differentiation differently, but it still gets the same results.

- T-cell Differentiation: na�ve T-cells that activate the immune response to T-regs (police cells) to signal B-cells, and it can be a good thing. But if the T-cells activate and differentiate the wrong cells, it will cause inflammation.

When T-cells differentiation is less abundant, there will be a higher incidence of food sensitivities, autoimmune disease, asthma, and allergies. But when there is an abundance of butyrate, the patients have lower rates of colon cancer and colitis.

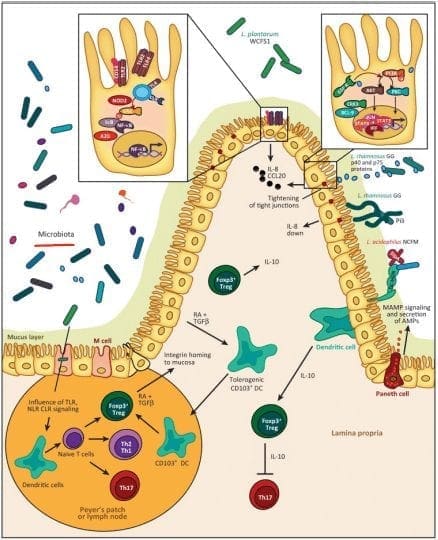

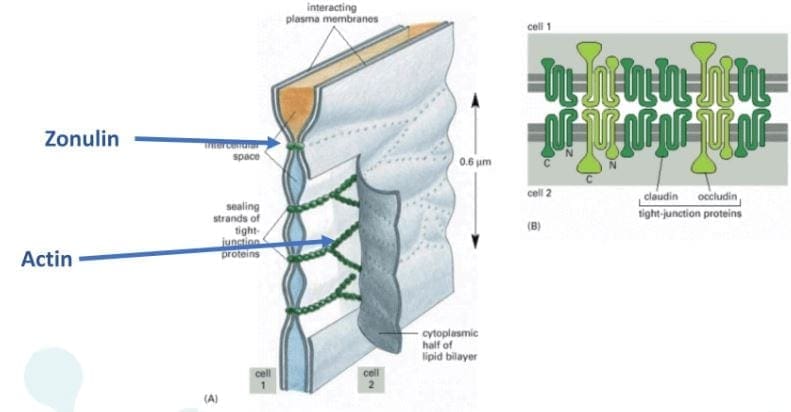

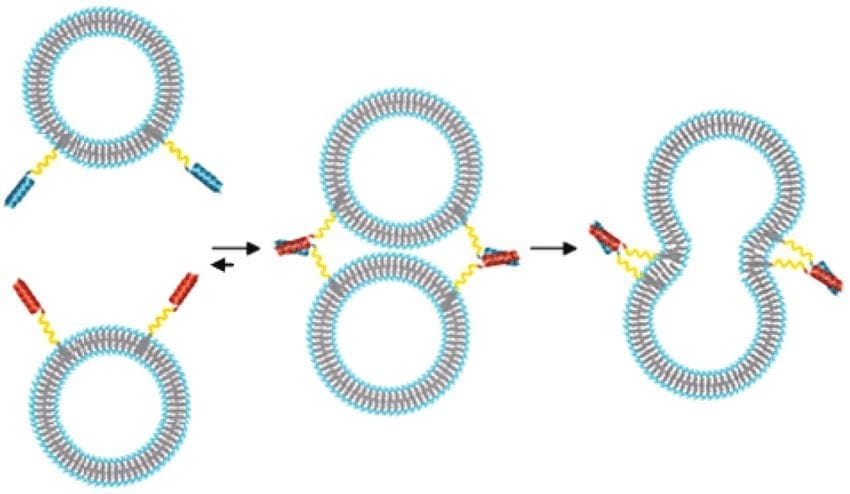

- Tight Junction: Lactobacillus plantarum and Lactobacillus rhamnosus are the reinforcers for the tight junction while inducing TLR (toll-like receptors) outside the intestinal epithelial walls, as well as increasing the abundance of zonulin-occludin into the tight junction.

SCFAs also play a vital role in the tight junction by lessening the extent propionate, inducing LOX (lipoxygenase) activity and increasing tight junction�s stability while reducing permeability.

Pathogens/Pathobionts: Can be an influence in the epithelial barriers as they can be opportunistic or conditionally pathogenic. Various pathogens like enteropathogenic E.coli can alternate the tight junction�s system. However, if there is a low abundance of L. plantarum, then it will lead to infections and disruption as well as disorganization of the actin cytoskeletons. This can be reversed by incubating the epithelial cells with L. plantarum to create a high density of actin filaments to the tight junction and repair itself.

- Zonulin, actin, and LPS: In the previous article, zonulin is the �gatekeeper� proteins that are responsible for opening and closing the tight junction. We talked about how if there is a low count of zonulin, it can cause inflammation, but if the zonulins are high, they can increase the IP and may facilitate enteric translocation by disassembling the tight junction. With less zonulin, it can be an overgrowth of b bacteria cells, thus causing more inflammation.

Actins are the structural and functional cells in the tight junction. However, if bacteria enter the actin cell walls, the bacteria will release toxins to the cell walls, it not only damages it but causes it to leak as well. This will make the damage actin cells not only paracellular but also intracellular to the damage actin cell walls.

Actin walls can also be affected when surfactants are involved. Surfactants are food agents and are known to affect the absorption of food substances in the gastrointestinal tract. They are not problematic, but when there is a low count on TEER, it can increase permeability and disband the tight junction.

LPS (Lipopolysaccharide) acts as a barrier and is recognized by the immune system as a marker for detecting bacterial pathogen invasion. It�s responsible for the development of inflammatory response in our gut.

Diet and Lifestyle

Diet and lifestyle contributions to the epithelial barrier integrity and breakdown. With the Wheat and Gut Zoomer helping out our intestinal barriers. Specific diets and lifestyles can also play effect to what is causing discomfort to our gut. These factors can cause our gut to be an imbalance, gastro discomfort, inflammation on our intestinal epithelial barriers.

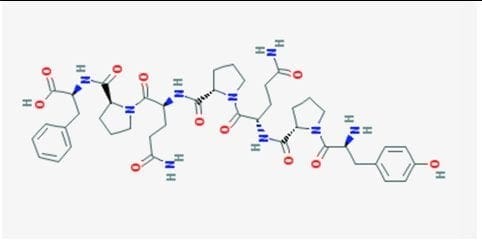

- Gluten: Gliadin is the main peptide that can cause gluten sensitivity. The gliadin protein can bind with many microbes, causing discomfort to our intestines and gut. Plus giving us an autoimmune disease, skin allergens, and chronic illnesses.

- Keto/High Fat Intake: Increase fat meals cause an increase of permeability, and if a patient has a high gram-negative, it will cause problems. But it can be beneficial, to those who don�t have the gram-negative bacteria in their system but, certain microbes like SCFAs do cling onto these fatty substances. In order to give patients an accurate result use both the Gut Zoomer and Wheat Zoomer to better the chances. Higher fat meals suppress beneficial bacteria. Causing a double risk of toxins in the bloodstream as well as inflammation.

- Alcohol: Patients are more willing to give up alcohol than gluten. Alcohol can be a stress reliever but can lead to addiction. It can be one of the causes of redistribution of the junctional proteins. One glass of wine a day is ok, but some patients don�t see alcohol as a mediator for reducing problems.

- Lectins: Lectins are contributors to permeability and impair the integrity of the intestinal epithelial layer, allowing passage through. Antibiotics for WGA can help lower the permeability of the intestinal wall barriers.

- Stress: Stress can cause discomfort and permeability in the intestinal epithelial barrier from high levels of cortisol.

Conclusion

Yes, gluten can cause inflammation in the intestinal epithelial barriers, but many factors that we discussed are also factors that can cause physiological assaults on the barrier�s integrity and stability of the intestinal ecosystem. Dr. Alexander Jimenez informs our patients about the importance of how functional medicine works with the combination of the Gut Zoomer and the Wheat Zoomer. This is not only protecting our gut but by giving us the information on what we can do to prevent a leaky gut.

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Gut and Intestinal Health, Health, Wellness

Today local chiropractors will be giving a description of the wheat zoomer. We will be giving a brief description of each panel, its markers, and the basic interpretations of the test. We will also be discussing the considerations for the patients and providers before we take The Wheat Zoomer test.

What is a Wheat Zoomer test?

The Vibrant wheat zoomer has 6 test in one to identify if the patient has wheat and gluten sensitivity. The Vibrant wheat zoomer does give our patients a thorough evaluation and we ask our patients if they started to be gluten-free or was gluten-free, either from birth or not and how much gluten-contained food did they eat. One of the best ways to ensure that our patients may have a gluten sensitivity is that if they have a food diary for us to look over and that way we can determine how severe of the wheat zoomer.

IgA vs IgG

In order for us to know about the wheat zoomer in our patient�s body, we must know about the immunoglobulins. The first one is IgA. IgA immunoglobulins are mucosal and are found primarily in the epithelial lining of the body: intestinal tract, lungs esophagus, blood-brain barrier and around internal organs. They are:

- The first line of defense.

- More accurate to our gut.

IgG immunoglobulins found in the blood system and are numerous in the body They are considered �systemic� and are non-specific to any one location. Not all IgG antibodies are sensitive though, some of them can indicate that an antigen has �leaked� into the blood and the immune system tagged that antigen as a �non-self�. And they are not diagnostic as IgG+IgA, but if IgA is absent, the antibodies are more relevant.

- If the patient is recently gluten-free, the antibodies will tell us that the antigen hasn�t cleared out in the patient�s system from past weeks of eating gluten.

Celiac

Celiac is a growing autoimmune disease, about 1% of the population is affective and 1 in 7 Americans have a reaction to wheat or wheat gluten disorder. The Vibrant test can determine a 99% sensitivity and 100% specify on the celiac antibodies.

- Total IgA and Total IgG measure both the IgA and IgG to determine the patient�s reactivity to gluten

- Cut off for IgA is 160 as well as a bottom 1/3rd

- Not all traditional markers for celiac disease doesn�t need to be elevated if tTg2 is elevated.

Intestinal Permeability

Zonulin is the gatekeeper for the intestines and controls nutrient flows and molecules across the membrane. It is a protein complex inside the intestinal tight junctions and can be increased by either gluten and high-fat meals.

Anti-Actin, especially f-Actin is in the smooth muscle of the intestines. Actin is part of the actomyosin complex. Vibrant can isolate f-Actin to get a more accurate picture of the patient�s immune response to the intestines. While antibodies in actin can identify intestinal destruction and indicate autoimmune diseases like connective tissue disease and autoimmune hepatitis.

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is produced by gram-negative enterobacteria. It is very potent and can cause inflammation. Plus it�s one of the indications of a leaky gut. Practitioners can draw additional lab test for cardiovascular, inflammatory markers, and diabetes/insulin resistance.

Here at Injury Medical Clinic, we suggest to our patients to try a Vibrant GutZoomer to identify the source of their ailments before we add the Vibrant WheatZoomer.

Gluten-mediated Autoimmunity

Fusion Peptide is the new addition to Wheat Zoomer in 2017. It is cross-linked to tTg and can identified celiac progression from 14 months to 4 years.

Differential Transglutaminases can detect autoimmune reactions to gluten that are not celiac or are becoming celiac. However, gluten is still a trigger but react differently in the celiac autoimmune disease such as:

- Transglutaminase 3= skin manifestations of autoimmunity like dermatitis herpetiformis, eczema, and psoriasis.

- Transglutaminases 6= neurological manifestations of autoimmunity in the cerebellum like gluten ataxia, gate abnormalities, balance and coordination issues.

Wheat Germ Agglutinin

Wheat Germ Agglutinin is the lectin component of wheat but, it is not a component to gluten. Dr. Jimenez can detect a patient’s low level of Vitamin D absorption from the patient�s results. And Wheat Germ Agglutinin is commonly used as an additive in supplements and the supplement can still be called gluten-free due to the different protein structure.

Gliadin, Glutenin, and Prodynorphin

Gliadin and glutenin are what makes up the super protein in gluten. Most people are reacting to the Gliadin portion of gluten and gliadin binds with tTg2 in celiac and binds zonulin to a leaky gut in patients. Gliadin reacts to any antigens can indicate a sensitivity to gluten in patients and gluteomorphin are peptides in wheat and react as a euphoria receptor to the brain. Prodynorphins antibodies can indicate that gluten reacts to signaling hormones and affect the patient’s mood.

Sadly though, patients do have a hard time withdrawing gluten in their diet since their antibodies are used to the compound and it up to us, here at Injury Medical Clinic to gently push our patients to have the will power to fix what is causing them to have ailments.

Wheat Allergin

Wheat Allergen is the true allergen body. Some patients that already know that they are allergic to wheat from a young age but it doesn�t decrease when wheat is eliminated and can remain long term after the allergic response happens.

Glutenin

Glutenin is the other part of the gluten compound. However it is less common to some people, but some individuals do show reactivity to glutenin, thus still have a gluten sensitivity. But there is no clinical difference to the reactivity to glutenin from high to low molecular weight.

Non-Gluten Wheat Proteins

Surprisingly Vibrant has an advantage to their test as they have a panel for patients that don�t have a gluten sensitivity but a wheat sensitivity. The Vibrant advantage to the unique non-gluten wheat panel shows us that:

- Proteins in wheat unrelated to gluten but relevant to immune reactions.

- It is 30% of the protein molecular weight of wheat.

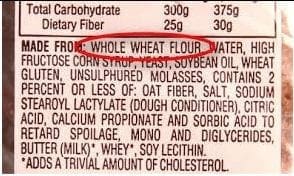

- Some individuals are more reactive to wheat proteins than gluten itself.

If they are trying to be gluten-free, patients still have to read the labels to see if any hidden wheat starches are in the ingredients. But not all food products are gluten-free if they have the wheat protein in them.

Conclusion

If the patient is trying to be gluten-free but previously ate gluten compound food. They can still feel the reaction if they discovered that they have a sensitivity to gluten by their practitioner. And must take precautions when they are reading the labels of the products they are going to buy and consume. In the next four articles, we will discuss what the Wheat Zoomer can provide as well as, discussing about what causes leaky gut, what actually goes on in our patient�s intestines, and wrapping up on what to do after the Wheat Zoomer heals and restores the gut barrier.

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Functional Medicine, Health, Nutrition

Mostly everyone in the world has a gluten allergy or gluten sensitivity when they consume food. When it comes to food that has the gluten compound, most people read the labels on the products that contain it and have cut the compound out of their diets completely. However, did you know that different foods and products have hidden gluten in them? Even though now and days we read labels from products, as well as, cutting off the source of the problem that is making us ill. Hidden additives like gluten, even in small amounts, can cause problems to those that are allergic or sensitive to the compound. Especially when it comes to the product itself, some regulations may or may not be required to label products that contain gluten.

What is Gluten?

Gluten is the main protein that is found in many grains such as wheat, rye, and barley. It is formed by two proteins which are glutenin and gliadin. And the word �gluten� is Latin for �glue� and when mixed with water, it rises and stretches. Most gluten can be found in some bread, pasta, cereal, and beer.

But in this article, we are going to inform you 8 products that have hidden gluten. Because here at Injury Medical Clinic, we take the time to talk with our patients on what ails their bodies and work on discovering what kind of food allergen or food sensitivity they may have. As well as, finding alternatives to prevent inflammation in their bodies.

8 Products with Hidden Gluten

Medications: Yes, you�ve read that correctly, there is gluten in medication. Surprisingly though, a lot of prescription medicine contains excipients (containing gluten) that actually binds the pills together. This is mostly found in generic over the counter medications but the labeling for the ingredients are not always there.

However, labeling standards are changing due to the Gluten in Medicine Disclosure Act of 2019. This was proposed on April 3, 2019, and introduced by Representatives Tim Ryan (D-OH) and Tom Cole (R-OK). The bill�s intent was to make it easier to identify gluten in prescription medicine and it is telling drug manufacturers that it is required to label medications with the list of their ingredients, their sources and whether the gluten compound is present.

Hopefully with enough signatures and votes that the bill will be passed, however, if you are taking medication and the labels look different; always verify with a pharmacist to see if it is correct. Plus, you can always talk with your pharmacist to confirm that your medicine is gluten-free, so that way you won�t get a bad reaction from it.

Sauces and gravy: Everybody loves any sauces and gravies in the meals they prepared and are excellent in mash potatoes and Thanksgiving dinners. But sauces like soy or teriyaki do contain wheat protein, hydrolyzed wheat starch or wheat flour. While others sometimes contain soy sauce or malt vinegar.

In any recipe that contains a type of sauce for the food you are preparing, especially in creamy sauces and gravies, mostly requires a roux; which is wheat flour mixed with butter. So, whenever you are at your favorite restaurant or have a favorite meal to prepare, get familiar with the sauces, so that way you can know that if they are gluten-free or not.

Starches: When we think of starches, our minds go to the potatoes. However, wheat can also be found in starches and starch derivatives. So, whenever you are looking at products that are starchy, look at the ingredient labels and for terms like �wheat starch�, �hydrolyzed wheat starch�, or �contains wheat.�

In order for starches that contain wheat starch to be gluten-free, the wheat compound must remove to less than 20 ppm. And especially in FDA regulated food labels, if the product says �contain wheat�, it is not safe. But food labels don�t apply to barley, rye, or oats, still continue to read the ingredient labels in the case for the wheat compound and if it is not there then the product is safe. For gluten-free starches for those who don�t want to miss out, tapioca starch, rice starch, and potato starch are perfect for frying.

Brown Rice Syrup: This type of sweetener is made from fermented brown rice with enzymes or from barley, which breaks down the starch and transforms it into sugar. Sadly though, this sweetener is not gluten-free and it can be used on its own or be used as an ingredient in a multi-ingredient product. Some companies use brown rice syrup in their products by listing it as �barley� or �barley malt.� And it is a bit problematic for those who have a gluten allergen to this sweetener.

Soups: Who doesn�t love soups. Soup is there for us when we are sick and for comfort when it gets really cold in the fall and winter seasons. But companies use wheat flour or wheat starch as a thickener for those creamier soups that we love in a can and those thickeners can be hidden in the ingredients label. So, if you want pre-packaged soup bases and canned soups for those colder seasons, be sure to read the labels carefully, especially for those creamed-based soup bases and bouillons because they might contain gluten.

Salad dressings: Did you know that many standard salad dressings can wheat flour, soy, or malt vinegar? Not only that but it can contain wheat or gluten-containing additives as a thickener. Plus salad dressings often have artificial colors, flavorings and many other additives that can contain gluten as a sub ingredient. However, if you want to be safe and not have gluten in your salad dressings, simply put in olive oil, lemon, salt, and pepper, and you got yourself a gluten-free salad dressing.

Chips and fries: Chips and fries are the staples for a good burger or hot dog on every barbeque events and parties. Yes, the potato that makes the chips and fries are gluten-free; but the seasonings like malt vinegar and wheat starch do contain gluten. And when we are frying cut potatoes into French fries and chips; the oil that is used to make them can be cross-contaminated with gluten-containing fried foods.

Processed meats: Meat is most likely to be the last place you think that has gluten. However, processed hamburger patties, meatballs, meatloaf, sausages, and deli meats contain gluten. Wheat-based fillers are used to either improve the texture of the meat or bind the meat together. Plus, seasoned or marinated eats can sometimes contain hydrolyzed wheat protein or soy sauce with breadcrumbs are added to bulk up the product.

Conclusion

So if you are at the grocery store getting some food for dinner or meal prepping, it is important to actually read the labeling of the products that you are buying. Whether you have a food allergy or food sensitivity to gluten or any food products, we here at Injury Medical Clinic, listen to what is causing our patients pain to their bodies and offer solutions to fix whatever ailments that the problem is causing.