by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Functional Medicine, Health, Wellness

The endocrine system is a network of glands and organs surrounding the body. While it is similar to the nervous system, it plays a vital role in controlling and regulating many body functions, as well as using chemical messengers called hormones. Since hormones circulate throughout the entire body, each type of hormone targets specific organs and tissues. The whole system is made up of glands and organs that release hormones into the body. Each has a different function to make sure that the human body is working correctly. If there is a disruption in one of the organs, it can cause problems and possibly lead to chronic illnesses later on.

Functioning The Endocrine System

In the endocrine system, it is responsible for regulating the body through the release of hormones. These hormones are secreted by the glands that travel through the bloodstream to various organs and tissues, telling them what to do or how to function in the body properly. Some of the bodily functions are controlled by the endocrine system. This includes the body�s metabolism, growth and development, heart rate, blood pressure, body temperature, appetite, and sleeping and waking cycles.

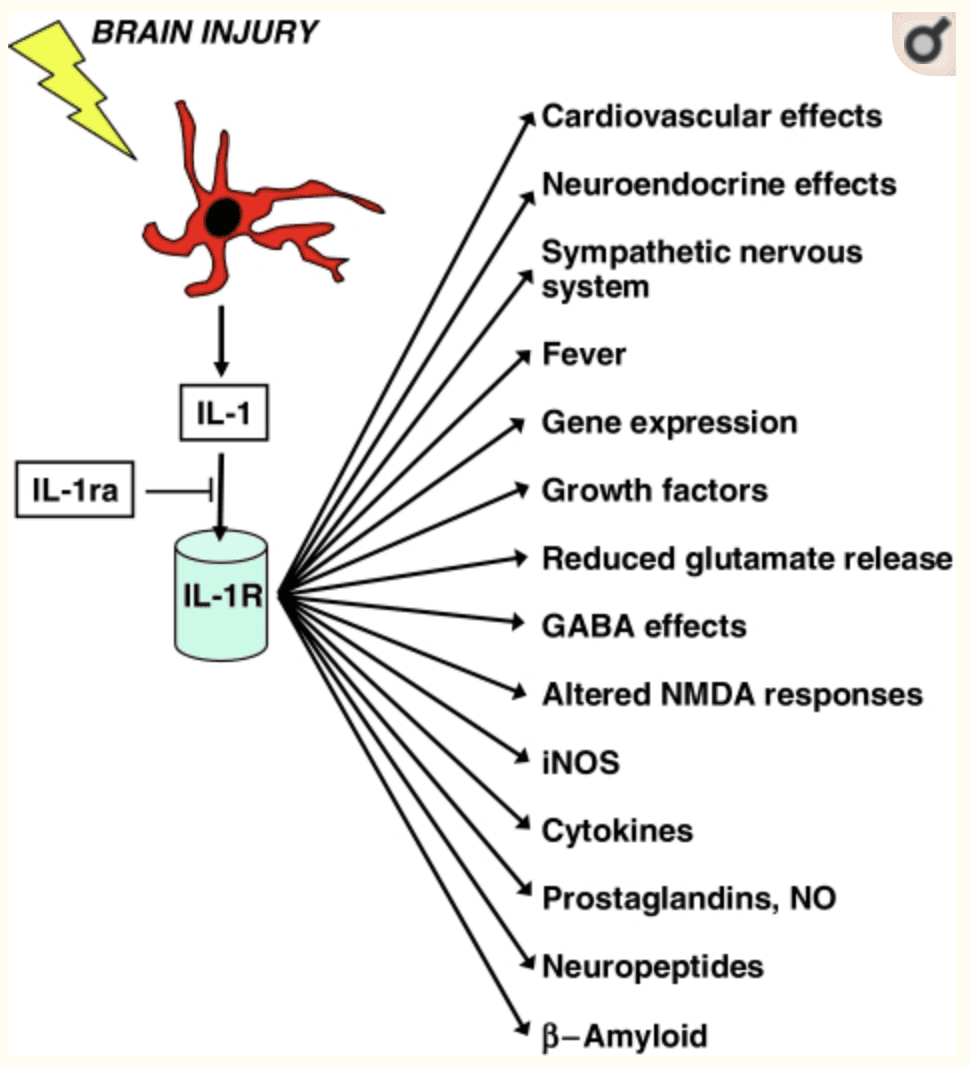

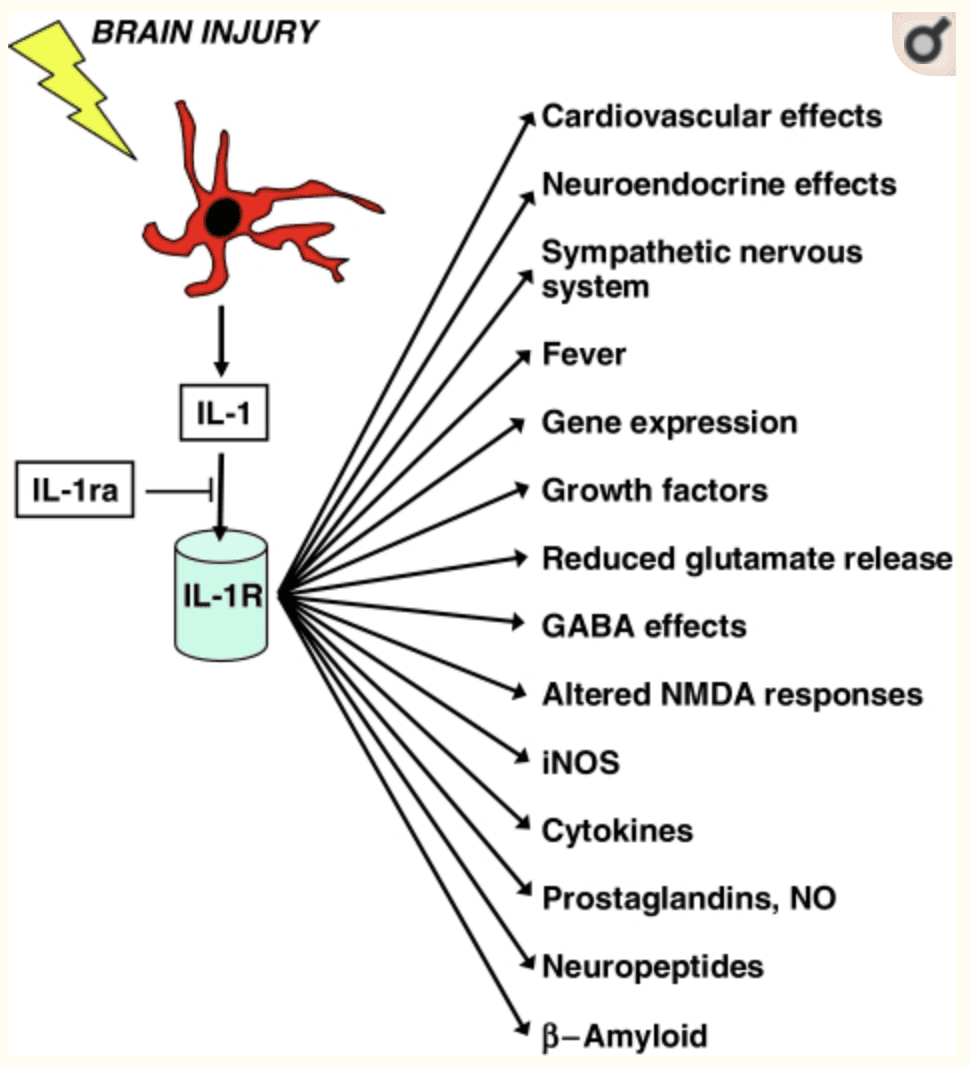

Studies have shown that the endocrine and the nervous system work closely together since the brain continuously sends instructions to the endocrine system while returning the favor, the endocrine glands receive feedback to the brain. With an intimate relationship, both methods are referred to as the neuroendocrine system. The neuroendocrine system is a mechanism where the hypothalamus maintains homeostasis, regulates reproduction, metabolism, and blood pressure. The neuroendocrine system works together with the immune system as they play an essential role in maintaining and restoring homeostasis in the body to function correctly.

The Organs of the Endocrine System

The endocrine system has a complex network of glands that secrete substances. The glands produce, store, and release throughout the body, targeting specific organs and tissues. Here are what each gland does in the endocrine system and what their functions are in the body.

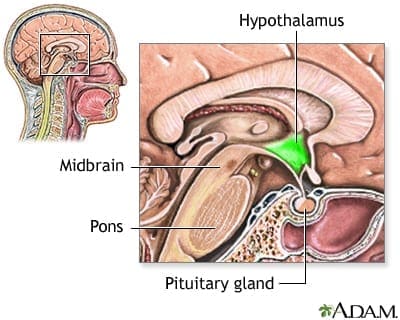

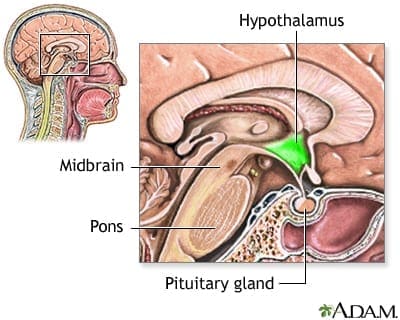

Hypothalamus

The hypothalamus gland is known as the master switchboard located in the center of the brain. Its role is significant because it controls and creates many hormones in the body. It also makes sure that it has to keep the body in a homeostasis state as much as possible. If the hypothalamus is not working correctly, it can cause problems for the body, and it can lead to a wide range of rare disorders.

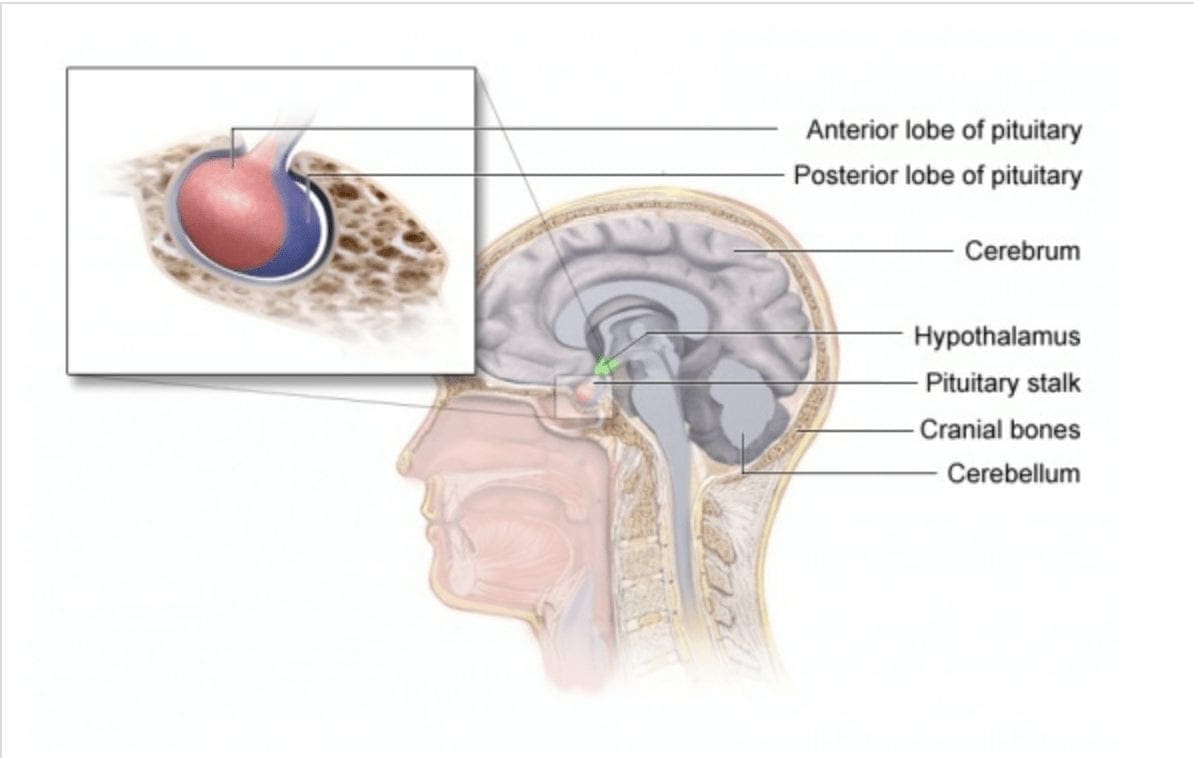

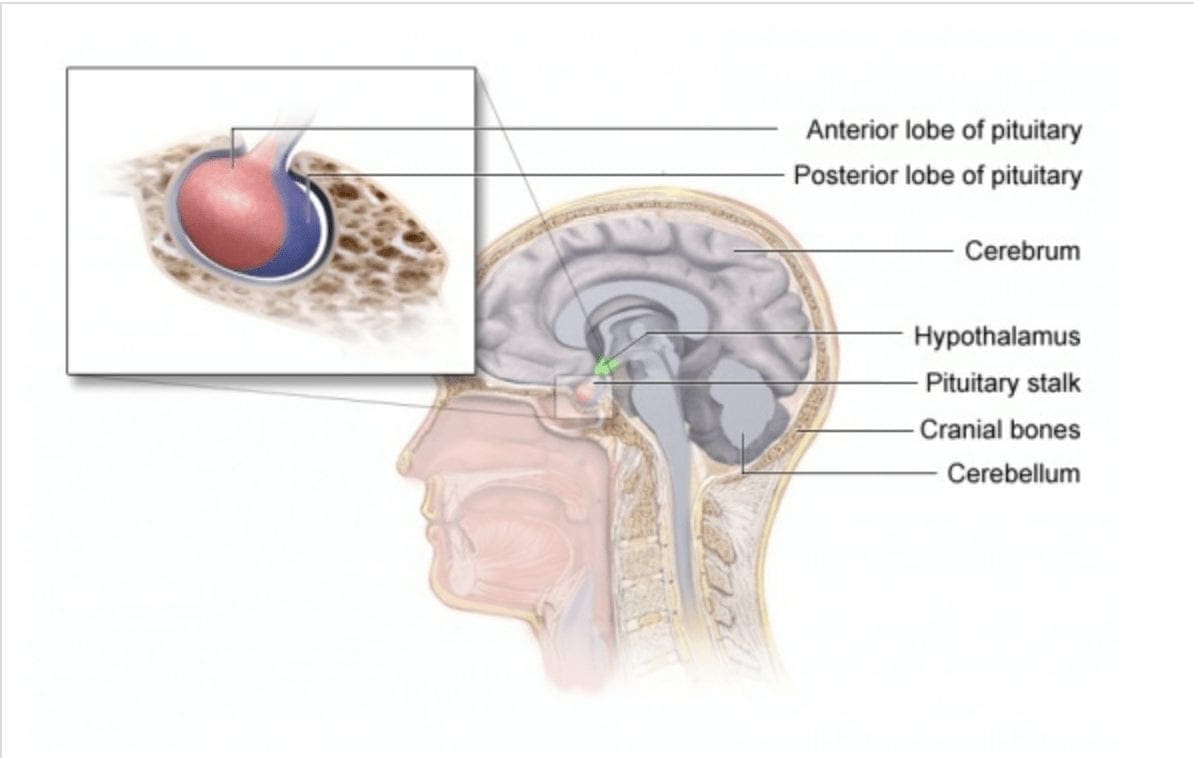

Pituitary

The pituitary gland is known as the master gland due to regulating the other endocrine glands activities. It plays an essential role by balancing hormone levels in the body, and together with the hypothalamus gland, they control the involuntary nervous system. This system helps manage the balance of the energy, heat, and water in the body. The pituitary gland also produces several hormones that can either regulate most of the other hormone glands or a direct effect on specific organs. When the endocrine glands produce too little or an excessive quantity of hormones, it can cause the body to be imbalanced.

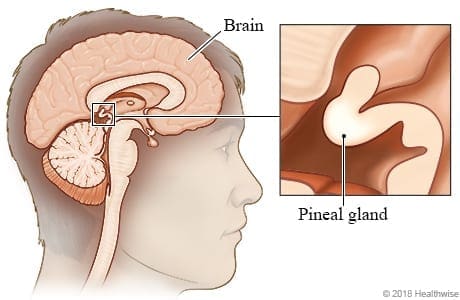

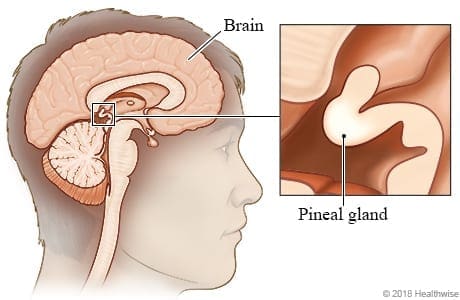

Pineal

The pineal gland is a small, pea-shaped gland that is in the brain and is sometimes called �the third eye.� It plays a role in producing and regulates hormones in females that may affect fertility and the menstrual cycle, including producing and excreting melatonin in the body. A 2016 study suggests that melatonin can help protect against cardiovascular diseases; however, there is still more research being done about the potential function of melatonin in the body.

When the pineal gland is not producing the correct amount of melatonin, it can cause an individual to have sleep disorders and accumulate an excessive quantity of calcium in the body. One of the most prominent symptoms that can cause pineal gland dysfunction is a change in circadian rhythms. A person can disrupt their circadian rhythm either sleeping too much or too little, having restless nights, and feeling sleepy at unusual times.

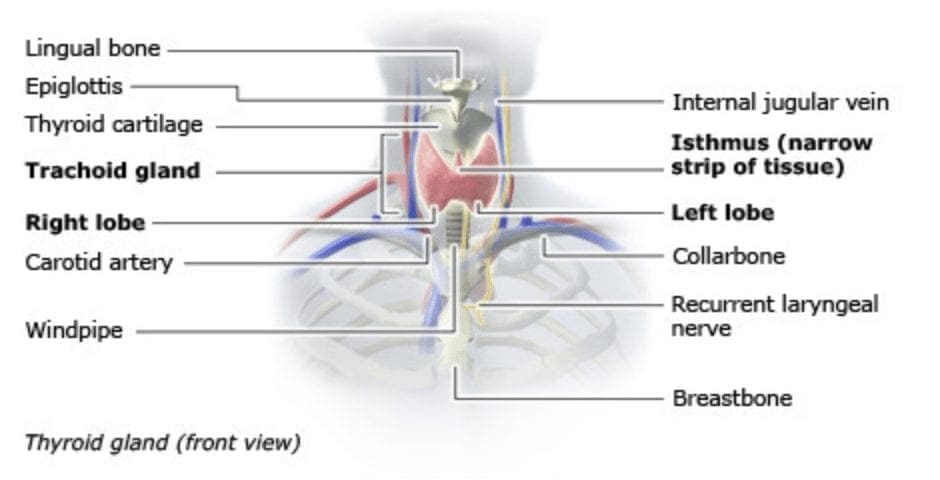

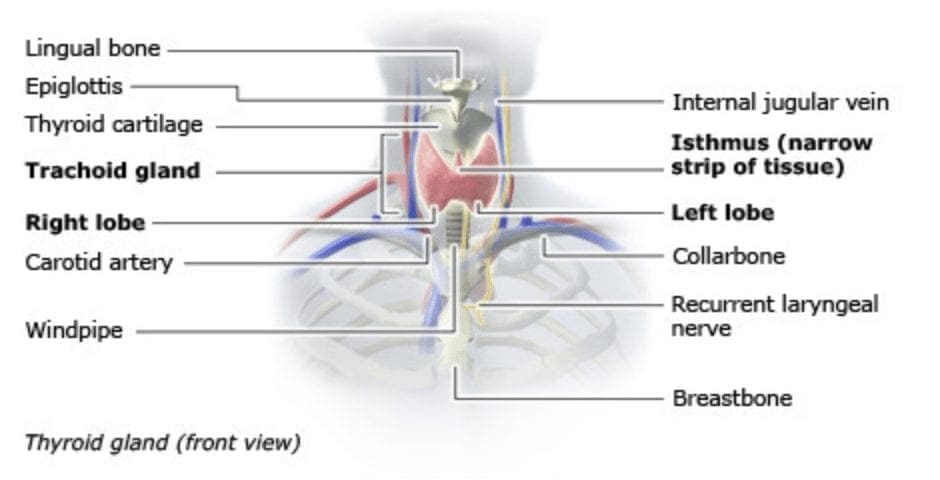

Thyroid

The thyroid gland a butterfly wing-shaped gland that is located in the anterior neck. It plays a huge vital role in the metabolism, growth, and development of the human body. It regulates many body functions by constantly releasing a steady amount of hormones in the bloodstream. When the thyroid produces too much or too little hormones, it can cause hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism in the body, causing many chronic illnesses in the body.

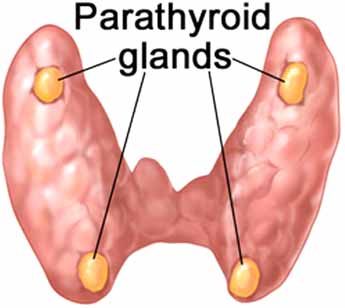

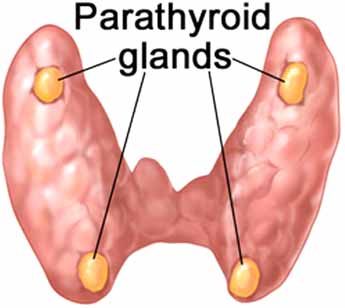

Parathyroid

The parathyroid gland is located behind the thyroid and plays a vital role in maintaining bone health, making sure the nervous system is running smoothly, and that muscles are pumping regularly. Parathyroid glands release PTH (parathyroid hormone), which regulates calcium in the bloodstream. Research shows that calcium is the only mineral in the body that has its very own dedicated regulatory gland. Calcium not only helps with bone strength, but it conducts electrical impulses in the nervous system and its energy in muscle cells. The PTH can also signal the kidneys and small intestines to save calcium from being digested.

When the parathyroid gland produces an excessive amount or a decreased amount of PTH, it can cause hyperparathyroidism and hypoparathyroidism leading the body to have many malfunctions, including weak bones in the body.

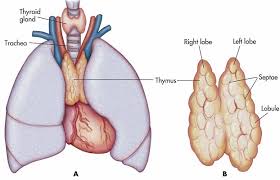

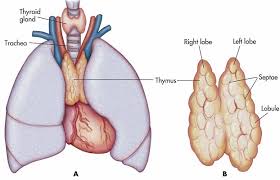

Thymus

The thymus gland is known as �the forgotten, but very important organ.� �It produces progenitor cells, which matures into T-cells and helps the organs in the immune system to grow properly. According to an article published by the NLM (U.S. National Library of Medicine), it stated that the thymus is the primary cell donor for the lymphatic system.

One of the most common diseases that can cause thymus dysfunction is MG (myasthenia gravis), PRCA (pure red cell aplasia), and hypogammaglobulinemia. These diseases can attack the body and cause chronic illnesses in the immune system.

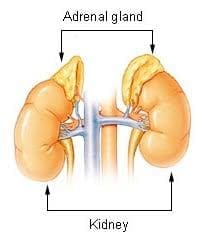

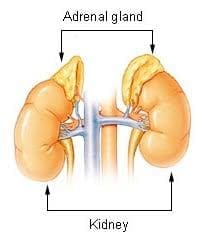

Adrenal

The adrenal glands are located on the top of the kidneys and help produce sex hormones and cortisol, they even work together with the pituitary glands. When cortisol is released from the adrenal glands, it can help with the response to stress and many essential functions in the body. When abnormal signals are disrupting the number of hormones that the pituitary glands telling the adrenal glands to produce. It can cause vitamin D to unbalance and many chronic illnesses.

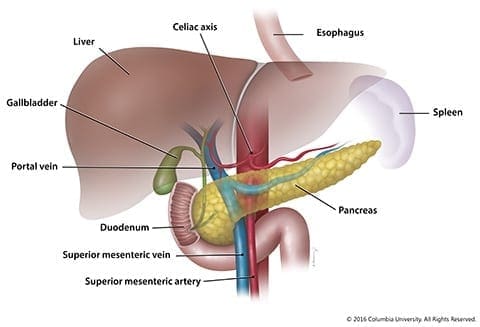

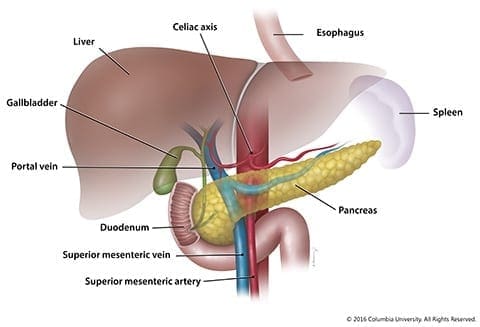

Pancreas

The pancreas is located in the abdomen and is part of the digestive system. It produces insulin, essential enzymes, and hormones that help break down food and sends it to the small intestine. When the pancreas produces the insulin hormone, it secretes it into the bloodstream, regulating the body�s glucose levels. There are many problems if the pancreas is not functioning correctly, causing the entire body to malfunction. If the pancreas is not producing enough insulin in the body, an individual is at risk for diabetes. Another factor is the development of pancreatic cancer caused by smoking or heavy drinking. The best way to keep a healthy pancreas is to maintain a healthy balanced diet.

Conclusion

The endocrine system is a network of glands and organs that surrounds the body. Each gland sends out hormones throughout the body and transfers to the specific organs that need these hormones to function correctly. If there is a disruption in the endocrine system, it can cause the body to malfunction and develop chronic illnesses.

October is Chiropractic Health Month. To learn more about it, check out Governor Abbott�s declaration on our website to get full details on this proclamation.

So the mechanisms of an autoimmune disease can be either by genetics or by environmental factors that can cause an individual to have problems in their body. There are many autoimmune diseases, both common and rare, that can affect the body. The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal and nervous health issues as well as functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions. We use functional health protocols to treat injuries or chronic disorders of the musculoskeletal system. To further discuss the subject matter above, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

References:

Bradford, Alina. �Parathyroid Glands: Facts, Function & Disease.� LiveScience, Purch, 5 May 2017, www.livescience.com/58980-parathyroid-glands.html.

Cherney, Kristeen. �Adrenal Glands.� Healthline, 26 July 2016, www.healthline.com/health/adrenal-glands.

Chu, Linda C, et al. �Diagnosis and Detection of Pancreatic Cancer.� Cancer Journal (Sudbury, Mass.), U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29189329.

Crosta, Peter. �Pancreas: Functions and Disorders.� Medical News Today, MediLexicon International, 26 May 2017, www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/10011.php.

Duggal, Neel. �5 Functions of the Pineal Gland.� Healthline, 7 Apr. 2017, www.healthline.com/health/pineal-gland-function.

Imrich, Richard. �The Role of Neuroendocrine System in the Pathogenesis of Rheumatic Diseases (Minireview).� Endocrine Regulations, U.S. National Library of Medicine, June 2002, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12207559.

Johnson, Jon. �Hypothalamus: Function, Hormones, and Disorders.� Medical News Today, MediLexicon International, 22 Aug. 2018, www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/312628.php.

Mannstadt, Michael, et al. �Hypoparathyroidism.� Nature Reviews. Disease Primers, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 31 Aug. 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28857066.

N/A, Uknown. �Circadian Rhythms.� National Institute of General Medical Sciences, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Aug. 2017, www.nigms.nih.gov/education/pages/factsheet_circadianrhythms.aspx.

Rosenow, E C, and B T Hurley. �Disorders of the Thymus. A Review.� Archives of Internal Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Apr. 1984, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6608930.

Seladi-Schulman, Jill. �Endocrine System Overview.� Healthline, 22 Apr. 2019, www.healthline.com/health/the-endocrine-system.

Sun, Hang, et al. �Effects of Melatonin on Cardiovascular Diseases: Progress in the Past Year.� Current Opinion in Lipidology, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Aug. 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4947538/.

Tirabassi, Giacomo, et al. �Adrenal Disorders: Is There Any Role for Vitamin D?� Reviews in Endocrine & Metabolic Disorders, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Sept. 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27761790.

Unknown, Unknown. �How Does the Pituitary Gland Work?� InformedHealth.org [Internet]., U.S. National Library of Medicine, 19 Apr. 2018, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279389/.

Unknown, Unknown. �How Does the Thyroid Gland Work?� InformedHealth.org [Internet]., U.S. National Library of Medicine, 19 Apr. 2018, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279388/.

Villines, Zawn. �Pineal Gland Function: Definition and Circadian Rhythm.� Medical News Today, MediLexicon International, 1 Nov. 2017, www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/319882.php.

Vorvick, Linda J., et al. �Endocrine Glands – Health Video: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia.� MedlinePlus, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 10 May 2019, medlineplus.gov/ency/anatomyvideos/000048.htm.

Yuen, Noah K, et al. �Hyperparathyroidism of Renal Disease.� The Permanente Journal, The Permanente Journal, 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27479950.

Zdrojewicz, Zygmunt, et al. �The Thymus: A Forgotten, But Very Important Organ.� Advances in Clinical and Experimental Medicine : Official Organ Wroclaw Medical University, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27627572.

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Functional Medicine, Health, Hyper Thyroid, Hypo Thyroid, Wellness

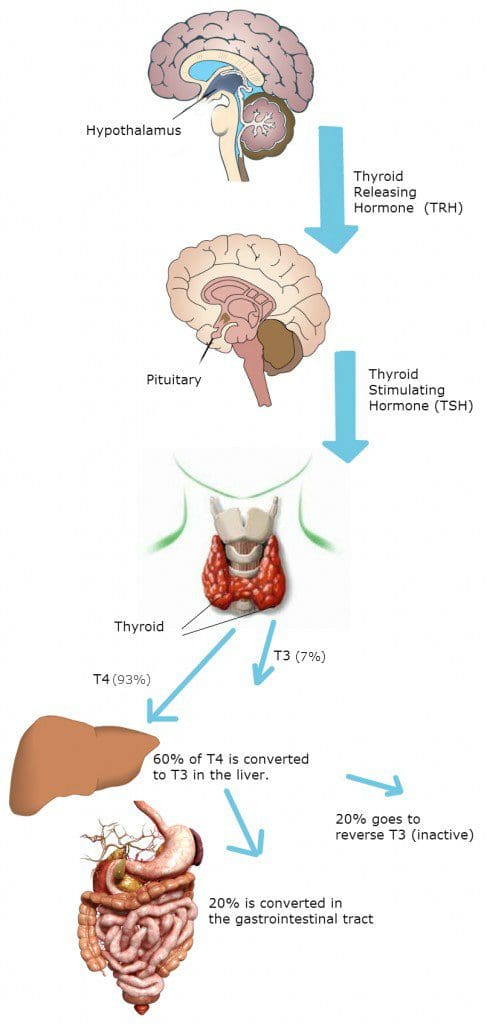

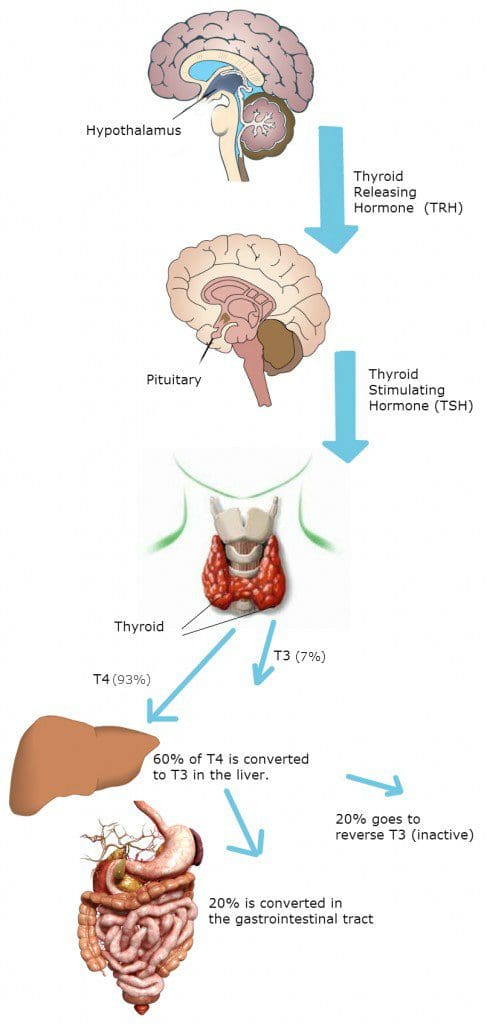

The thyroid is a small, butterfly-shaped gland that is located in the anterior neck producing T3 (triiodothyronine) and T4 (tetraiodothyronine) hormones. These hormones affect every single tissue and regulate the body�s metabolism while being part of an intricate network called the endocrine system. The endocrine system is responsible for coordinating many of the body’s activities. In the human body, the two major endocrine glands are the thyroid glands and the adrenal glands. The thyroid is controlled primarily by TSH (thyroid-stimulating hormone), which is secreted from the anterior pituitary gland in the brain. The anterior pituitary gland can stimulate or halt the secretion to the thyroid, which is a response only gland in the body.

Since the thyroid glands make T3 and T4, iodine can also help with the thyroid hormone production. The thyroid glands are the only ones that can absorb the iodine to help hormone growth. Without it, there can be complications like hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, and Hashimoto�s disease.

Thyroid Influences on The Body Systems

The thyroid can help metabolize the body, such as regulating heart rate, body temperature, blood pressure, and brain function. Many of the body�s cells have thyroid receptors that the thyroid hormones respond to. Here are the body systems that the thyroid helps out.

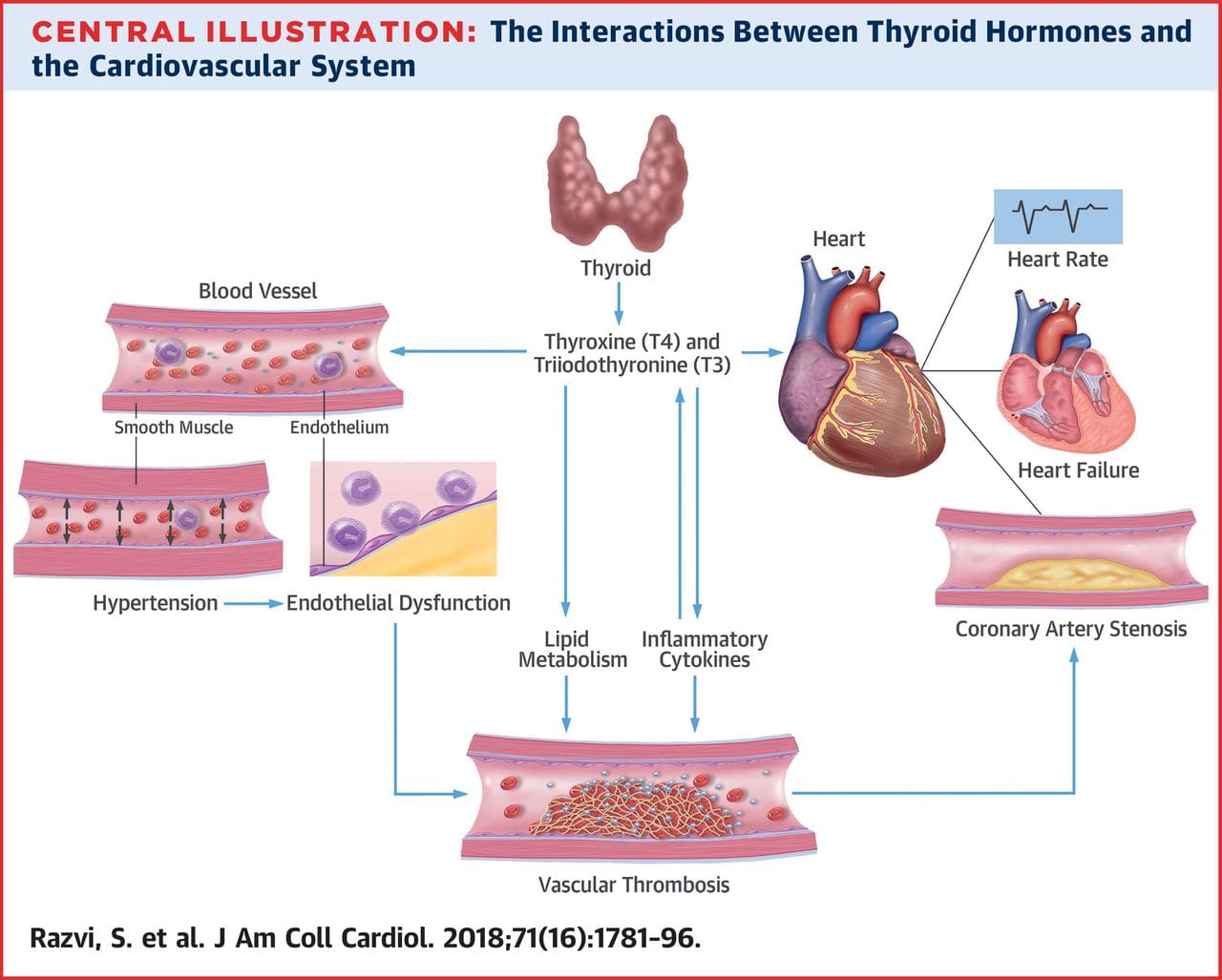

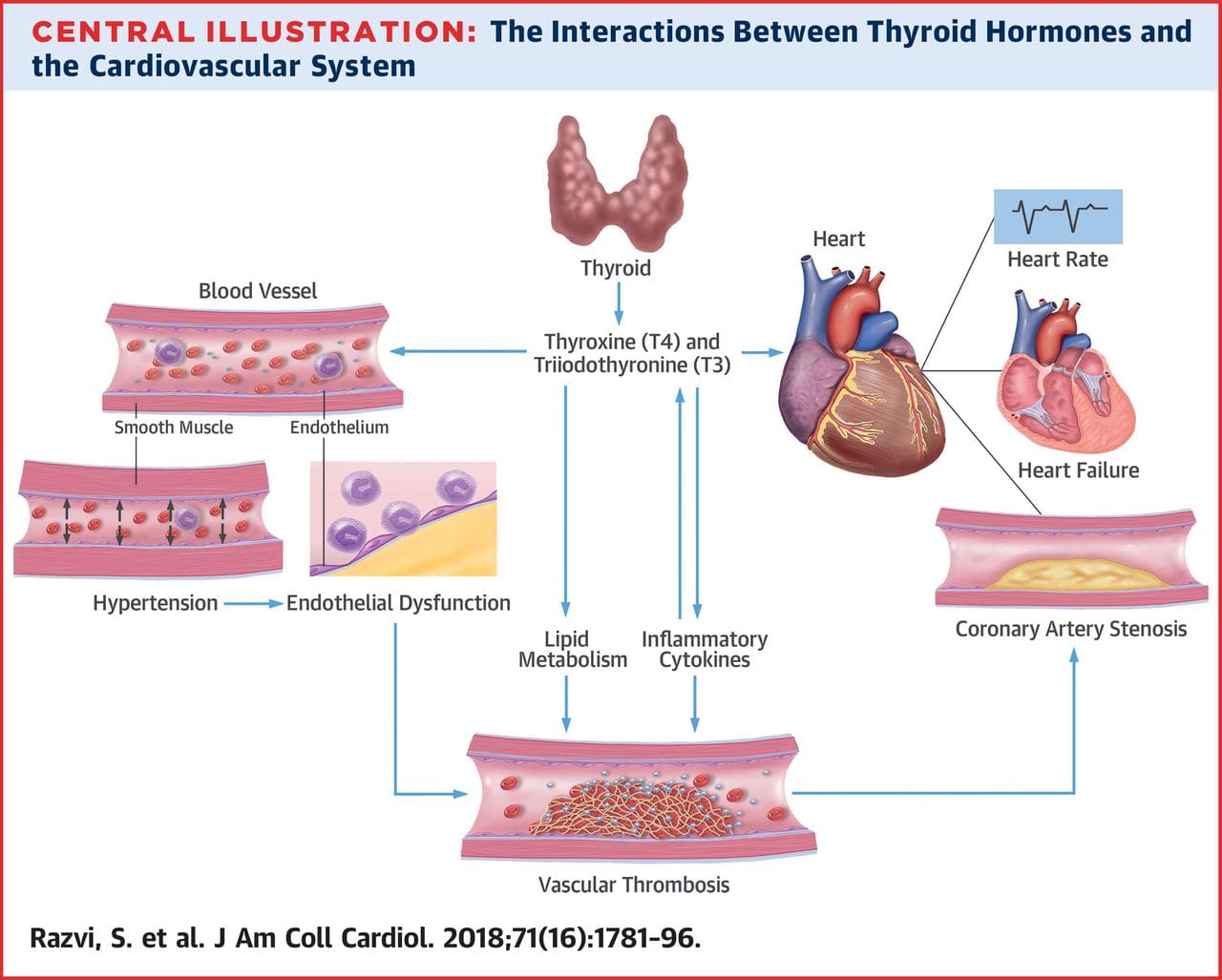

Cardiovascular System and the Thyroid

Under normal circumstances, the thyroid hormones help increase the blood flow, cardiac output, and heart rate in the cardiovascular system. The thyroid can influence the heart�s �excitement,� causing it to have an increasing demand for oxygen, therefore increasing the metabolites. When an individual is exercising; their energy, their metabolism, as well as their overall health, feels good.

The thyroid actually strengthens the heart muscle, while decreasing the external pressure because it relaxes the vascular smooth muscle. This results in a decrease of arterial resistance and diastolic blood pressure in the cardiovascular system.

When there is an excess amount of thyroid hormone, it can increase the heart�s pulse pressure. Not only that, the heart rate is highly sensitive to an increase or decrease in the thyroid hormones. There are a few related cardiovascular conditions listed below that can be the result of an increased or decreased thyroid hormone.

- Metabolic Syndrome

- Hypertension

- Hypotension

- Anemia

- Arteriosclerosis

Interestingly, iron deficiency can slow the thyroid hormones as well as increase the production of the hormones causing problems in the cardiovascular system.

The Gastrointestinal System and the Thyroid

The thyroid helps the GI system by stimulating carbohydrate metabolism and fat metabolism. This means that there will be an increase in glucose, glycolysis, and gluconeogenesis as well as an increased absorption from the GI tract along with an increase in insulin secretion. This is done with an increased enzyme production from the thyroid hormone, acting on the nucleus of our cells.

The thyroid can increase the basal metabolic rate by helping it increase the speed of breaking down, absorbing, and the assimilation of the nutrients we eat and eliminate waste. The thyroid hormone can also increase the need for vitamins for the body. If the thyroid is going to regulate our cell metabolism, there has to be an increased need for vitamin cofactors because the body needs the vitamins to make it function properly.

Some conditions can be impacted by thyroid function, and coincidentally can cause thyroid dysfunction.

- Abnormal cholesterol metabolism

- Overweight/underweight

- Vitamin deficiency

- Constipation/diarrhea

Sex Hormones and the Thyroid

The thyroid hormones have a direct impact on ovaries and an indirect impact on SHBG (sex hormone-binding globulin), prolactin, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion. Women are dramatically more affected by thyroid conditions than men due to hormones and pregnancy. There is also another contributing factor that women share, their iodine vitals and their thyroid hormones through the ovaries and the breast tissue in their bodies. The thyroid can even have either a cause or contribution to pregnancy conditions like:

- Precocious puberty

- Menstrual issues

- Fertility issues

- Abnormal hormone levels

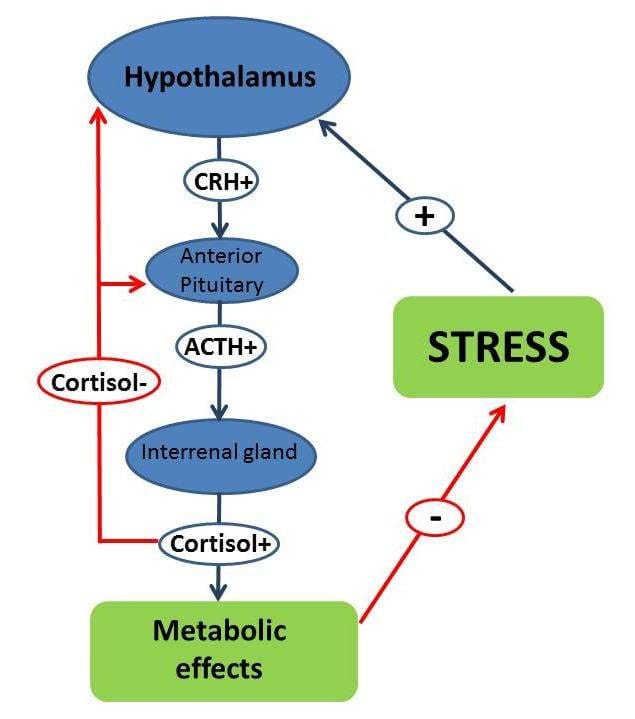

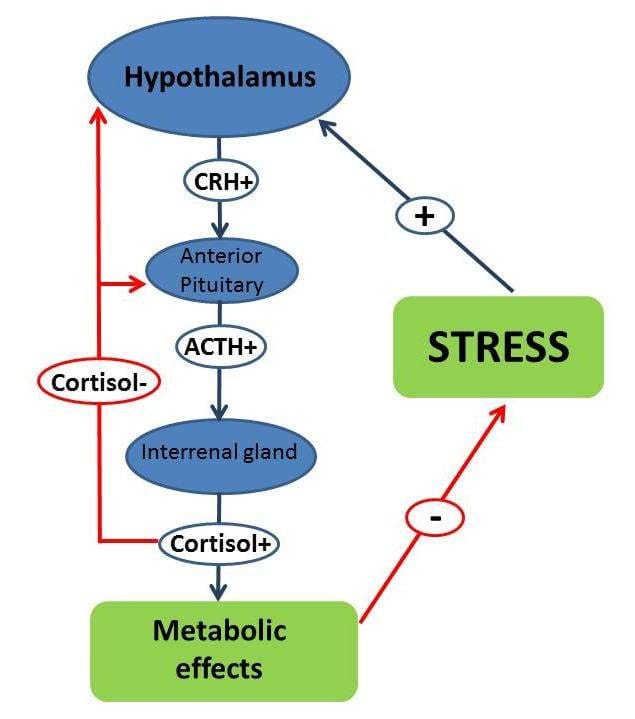

HPA Axis and the Thyroid

The HPA axis�(Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis) modulates the stress response in the body. When that happens, the hypothalamus releases the corticotropin-releasing hormone, it triggers the ACH (acetylcholine hormone) and the ACTH (adrenocorticotropic hormone) to act on the adrenal gland to release cortisol. Cortisol is a stress hormone that can lower inflammation and increase carbohydrate metabolism in the body. It can also trigger a cascade of �alarm chemicals� like epinephrine and norepinephrine (fight or flight response). If there is an absence of lowered cortisol, then the body will desensitize for the cortisol and the stress response, which is a good thing.

When there is a higher level of cortisol in the body, it will decrease the thyroid function by lowering the conversion of the T4 hormone to T3 hormone by impairing the deiodinase enzymes. �When this happens, the body will have a less functional thyroid hormone concentration, since the body can�t tell the difference of a hectic day at work or running away from something scary, it can either be very good or horrible.

Thyroid Problems in the Body

The thyroid can produce either too much or not enough hormones in the body, causing health problems. Down below are the most commonly known thyroid problems that will affect the thyroid in the body.

- Hyperthyroidism: This is when the thyroid is overactive, producing an excessive amount of hormones. It affects about 1% of women, but it�s less common for men to have it. It can lead to symptoms such as restlessness, bulging eyes, muscle weakness, thin skin, and anxiety.

- Hypothyroidism: This is the opposite of hyperthyroidism since it can�t produce enough hormones in the body. It is often caused by Hashimoto�s disease and can lead to dry skin, fatigue, memory problems, weight gain, and a slow heart rate.

- Hashimoto�s disease: This disease is also known as chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis. It affects about 14 million Americans and can occur in middle-aged women. This disease develops when the body�s immune system mistakenly attacks and slowly destroys the thyroid gland and its ability to produce hormones. Some of the symptoms that Hashimoto�s disease causes are a pale, puffy face, fatigue, enlarged thyroid, dry skin, and depression.

Conclusion

The thyroid is a butterfly-shaped gland located in the anterior neck that produces hormones that help function the entire body. When it doesn�t work correctly, it can either create an excessive amount or decrease the number of hormones. This causes the human body to develop diseases that can be long term.

In honor of Governor Abbott’s proclamation, October is Chiropractic Health Month. To learn more about the proposal on our website.

The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal, and nervous health issues as well as functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions. We use functional health protocols to treat injuries or chronic disorders of the musculoskeletal system. To further discuss the subject matter above, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

References:

America, Vibrant. �Thyroid and Autoimmunity.� YouTube, YouTube, 29 June 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?feature=youtu.be&v=9CEqJ2P5H2M.

Clinic Staff, Mayo. �Hyperthyroidism (Overactive Thyroid).� Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 3 Nov. 2018, www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/hyperthyroidism/symptoms-causes/syc-20373659.

Clinic Staff, Mayo. �Hypothyroidism (Underactive Thyroid).� Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 4 Dec. 2018, www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/hypothyroidism/symptoms-causes/syc-20350284.

Danzi, S, and I Klein. �Thyroid Hormone and the Cardiovascular System.� Minerva Endocrinologica, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Sept. 2004, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15282446.

Ebert, Ellen C. �The Thyroid and the Gut.� Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, July 2010, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20351569.

Selby, C. �Sex Hormone Binding Globulin: Origin, Function and Clinical Significance.� Annals of Clinical Biochemistry, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Nov. 1990, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2080856.

Stephens, Mary Ann C, and Gary Wand. �Stress and the HPA Axis: Role of Glucocorticoids in Alcohol Dependence.� Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2012, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3860380/.

Wallace, Ryan, and Tricia Kinman. �6 Common Thyroid Disorders & Problems.� Healthline, 27 July, 2017, www.healthline.com/health/common-thyroid-disorders.

Wint, Carmella, and Elizabeth Boskey. �Hashimoto’s Disease.� Healthline, 20 Sept. 2018, www.healthline.com/health/chronic-thyroiditis-hashimotos-disease.

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Functional Medicine, Gut and Intestinal Health, Health, Wellness

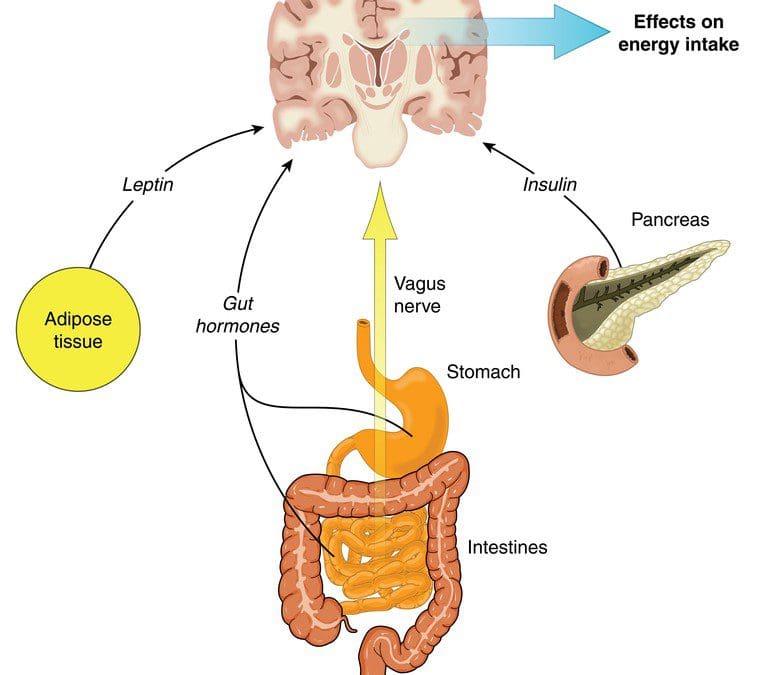

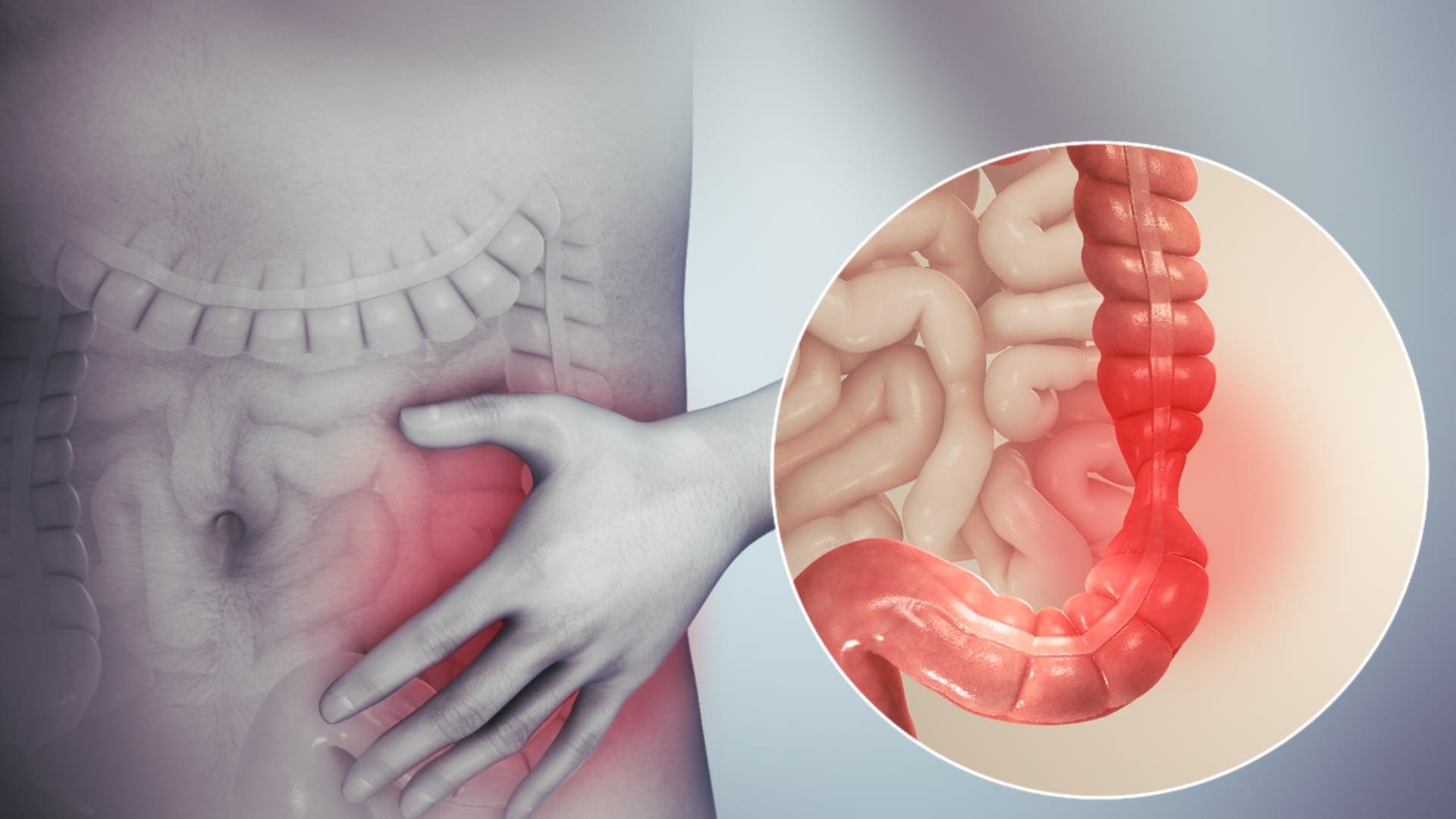

The gut-brain connection is essential in the body. If an individual has a leaky gut that is causing inflammation, it can send the signal to the brain and it can create problems like neurotransmitter dysfunction to systems that just don�t connect. The leaky gut can lead to brain dysfunction or brain dysfunction can lead to leaky gut. Sometimes an autoimmunity disease in the stomach can lead to a disruption in the mind. Then, brain disruption can also lead to inflammation in the gut. It�s a never-ending loop that the brain and gut can go on forever. Studies have stated that gut microbiota appears to influence the development of emotional behaviors like stress, pain modulation systems, and brain neurotransmitter systems.

The Brain System to the Gut System

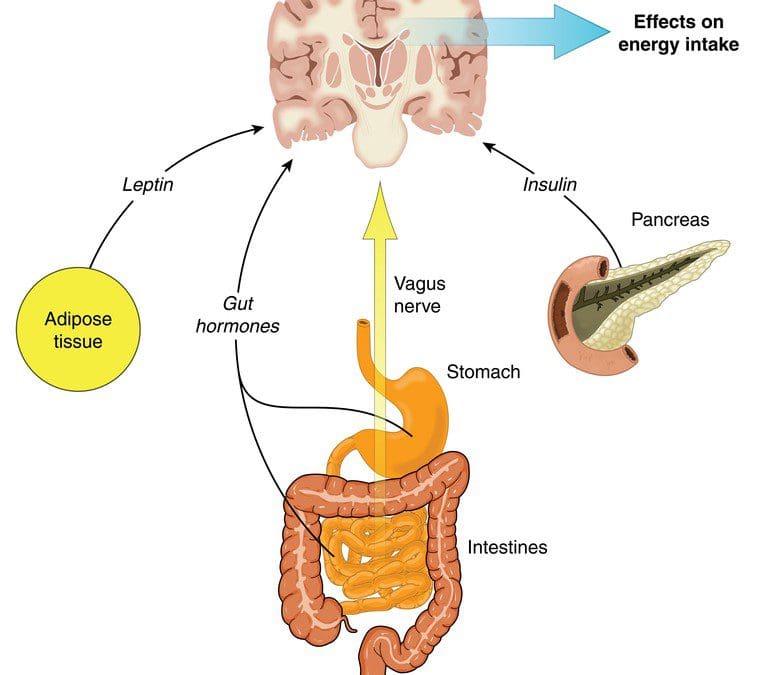

The brain is the main control room that controls the body�s system and how the body should behave. The human brain also contains neuron cells that are found in the central nervous system. With the gut-brain connection, two critical systems help send the signal to the brain and the gut; these are known as the vagus nerve and the neurotransmitters.

The Vagus Nerve

There are approximately 100 billion neurons in the brain, while the gut contains about 500 million neurons, which is connected to the brain through the nerves in the nervous system. The vagus nerve is one of the most significant nerves that send signals back and forth to the brain and the gut. When the body is stressed, the stress signal inhibits the vagus nerve, and it can cause problems to the gut-brain connection. Animal studies have shown that any stress that is in the animal�s body can cause gastrointestinal issues and PTSD. While another study stated that individuals that have IBS (irritable bowel syndrome) have a reduced function of the vagus nerve.

There are ways to reduce the stress hormone so that the vagus nerve can function properly and send the right signals to the gut and the brain. Probiotic foods can help lower the amount of stress hormone in the bloodstream. When that happens, the body can start healing naturally when the stress is reduced; however, if the vagus nerve is damaged, then the probiotic has no effect.

Neurotransmitters

Neurotransmitters are produced chemically in the brain by controlling feelings and emotions in the body. Since the brain and gut are connected to neurotransmitters, the neurotransmitters can create these compounds that help contribute to the body. In the brain, the neurotransmitter can produce serotonin to make the person feel happy and help control their body�s biological clock.

In the gut, there are trillions of microbes that live there, and interestingly researchers stated that serotonin is mainly being produced by the gut system. Another neurotransmitter that is provided in the gut is called GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid), which helps control the feeling of fear and anxiety. When the brain feels overly anxious or has been through a traumatic experience that has caused them to be fearful, it can cause them to be hypersensitive and can cause a chemical imbalance to the gut, causing inflammation or leaky gut if it is severe.

The Gut System to the Brain System

The gut microbes can produce neurotransmitters to send to the brain, protect the intestinal barrier and the tight junction integrity, regulate the mucosal immune system, and modulates the enteric sensory afferents. The gut microbe produces a lot of SCFA (short-chain fatty acids) that form a barrier between the brain and blood flow called the blood-brain barrier. The blood-brain barrier protects the CNS (central nervous system) from toxins, pathogens, inflammation, injury, and disease.

The gut microbes also metabolize bile and amino acids to help produce other chemicals that affect the brain. When the body is stressed, it can reduce the production of bile acid by gut bacteria and alter the genes that are involved. When that stress is still creating problems in mind, the gut can develop gastrointestinal issues that will destroy the permeability barrier that is protecting the intestines.

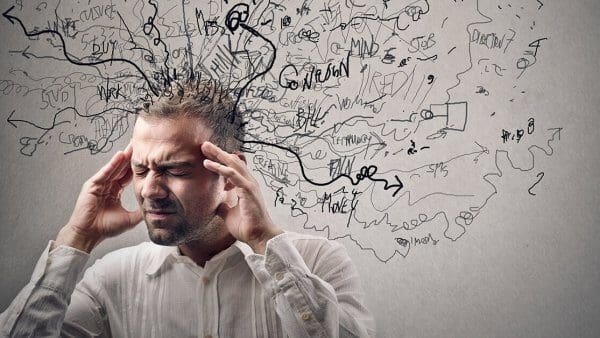

The gut-brain connection plays an essential role in the body�s immune system as it controls inflammation and what passes into the body. Since the immune system controls inflammation, if it is turned on for too long, inflammation can occur as well as several brain disorders like depression and Alzheimer�s disease. Stress can even disrupt the gut by causing contractions to the GI tract, make inflammation worse in the intestinal permeability, and making the body more at risk to infections.

When the body starts to alleviate stress, it can naturally heal itself, and the gut-brain connection can begin functioning normally. With changes in a person�s eating habits and lifestyle, it can drastically change a person�s mood and recover from intestinal ailments they may have. If the brain feels right, then the gut feels good as well. They work together side by side to make sure that the body is functioning correctly. When either one is being disrupted, then the body does not function properly.

Conclusion

Therefore, the gut-brain connection is vital to the body. Neurotransmitters and other components that are in both systems work together to make sure that the body is working correctly. When one of the connections is being disrupted, however, the body can develop many chronic illnesses even if the person seems fine. By altering little things like changing a person�s diet and lifestyle, it can help improve the body and bring the balance back to the gut-brain connection.

In honor of Governor Abbott’s proclamation, October is Chiropractic Health Month. To learn more about the proposal on our website.

The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal, and nervous health issues as well as functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions. We use functional health protocols to treat injuries or chronic disorders of the musculoskeletal system. To further discuss the subject matter above, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

References:

Anguelova, M, et al. �A Systematic Review of Association Studies Investigating Genes Coding for Serotonin Receptors and the Serotonin Transporter: I. Affective Disorders.� Molecular Psychiatry, U.S. National Library of Medicine, June 2003, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12851635.

Bravo, Javier A, et al. �Ingestion of Lactobacillus Strain Regulates Emotional Behavior and Central GABA Receptor Expression in a Mouse via the Vagus Nerve.� Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, National Academy of Sciences, 20 Sept. 2011, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21876150.

Carabotti, Marilia, et al. �The Gut-Brain Axis: Interactions between Enteric Microbiota, Central and Enteric Nervous Systems.� Annals of Gastroenterology, Hellenic Society of Gastroenterology, 2015, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4367209/.

Daneman, Richard, and Alexandre Prat. �The Blood-Brain Barrier.� Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 5 Jan. 2015, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4292164/.

Herculano-Houzel, Suzana. �The Human Brain in Numbers: a Linearly Scaled-up Primate Brain.� Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, Frontiers Research Foundation, 9 Nov. 2009, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2776484/.

Lucas, Sian-Marie, et al. �The Role of Inflammation in CNS Injury and Disease.� British Journal of Pharmacology, Nature Publishing Group, Jan. 2006, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1760754/.

Mayer, Emeran A, et al. �Gut/Brain Axis and the Microbiota.� The Journal of Clinical Investigation, American Society for Clinical Investigation, 2 Mar. 2015, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4362231/.

Mayer, Emeran A. �Gut Feelings: the Emerging Biology of Gut-Brain Communication.� Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 13 July 2011, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3845678/.

Mazzoli, Roberto, and Enrica Pessione. �The Neuro-Endocrinological Role of Microbial Glutamate and GABA Signaling.� Frontiers in Microbiology, Frontiers Media S.A., 30 Nov. 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5127831/.

Pellissier, Sonia, et al. �Relationship between Vagal Tone, Cortisol, TNF-Alpha, Epinephrine and Negative Affects in Crohn’s Disease and Irritable Bowel Syndrome.� PloS One, Public Library of Science, 10 Sept. 2014, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25207649.

Rooks, Michelle G, and Wendy S Garrett. �Gut Microbiota, Metabolites and Host Immunity.� Nature Reviews. Immunology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 27 May 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27231050.

Sahar, T, et al. �Vagal Modulation of Responses to Mental Challenge in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder.� Biological Psychiatry, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 1 Apr. 2001, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11297721.

Yano, Jessica M, et al. �Indigenous Bacteria from the Gut Microbiota Regulate Host Serotonin Biosynthesis.� Cell, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 9 Apr. 2015, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4393509/.

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Functional Medicine, Health, Wellness

Autoimmune disease is the disease of the modern era. It is a condition where the body�s immune system mistakenly attacks the body. Since the body�s immune system usually guards against bacteria and viruses, it can sense the foreign cells and send out fighter cells to attack them. When it�s an autoimmune disease, however, the immune system starts to make mistakes to certain parts of the body. It starts attacking the joints, the skin, or the musculoskeletal system as foreign cells and attacking them. The immune system releases autoantibody proteins to attack the healthy cells, thus causing autoimmune disease in the body.

What Triggers the Activation of the Autoimmune Mechanism?

Surprisingly, the body�s antibodies go through a process by cleaning up the old and damaged cells, so that way, new healthy cells can grow and replace the old cells. Although if the body has an excessive number of antibodies in their system, it can cause the individual to have an autoimmune disease. Research has shown that a part of the autoimmune ecology, the influence of environmental exposure can not only develop autoimmune disorder but shape the function of the immune system.

Another study stated that approximately 30% of all autoimmune diseases come from genetic disposition while 70% is due to environmental factors, including toxic chemicals, dietary components, gut dysbiosis, and infections in the body. So some of the ecological factors that are included are adjuvants (immunostimulant effects). These are typically used in vaccines to produce a more effective immunization reaction.

Researchers stated that molecular mimicry is one of the mechanisms, where a foreign antigen shares a sequence or structural similarities with self-antigens. This means that any infections that can initiate and maintain autoimmune responses can lead to specific tissue damage in the body. It is a phenomenon that molecular mimicry and cross-reactivity are identical. Cross-reactivity is significant when it comes to food allergies and is often responsible for many disorders. It affects the scope of the disease, the reliability of diagnostic testing, and has implications for any current and potential therapies.

Common and Rare Autoimmune Diseases

The primary function of the immune system is to repair the body with new cells. Individuals with an autoimmune disease will have many chronic illnesses that are both common and rare when they are being diagnosed. Below is a list of autoimmune diseases that range from common to some of the rarer autoimmune conditions an individual may experience.

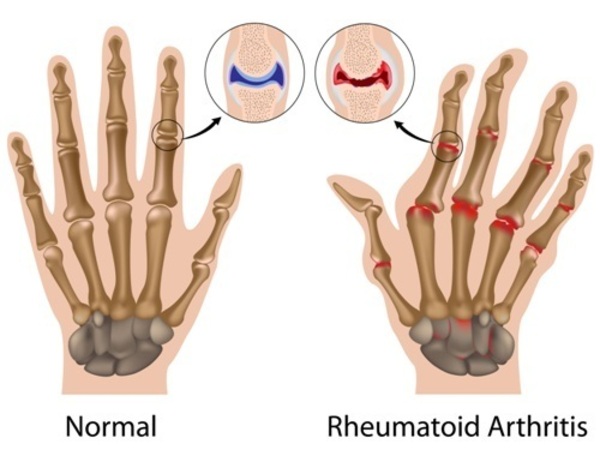

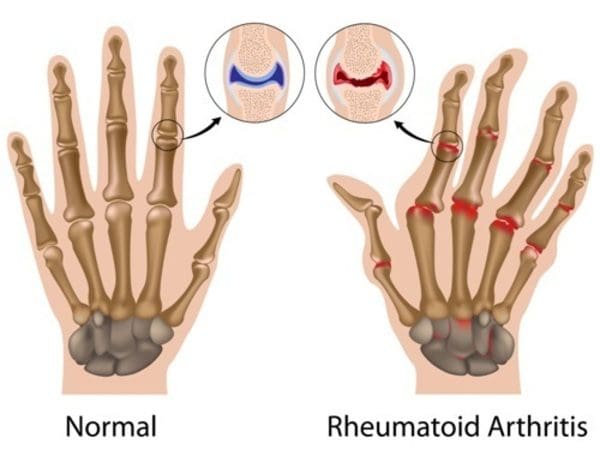

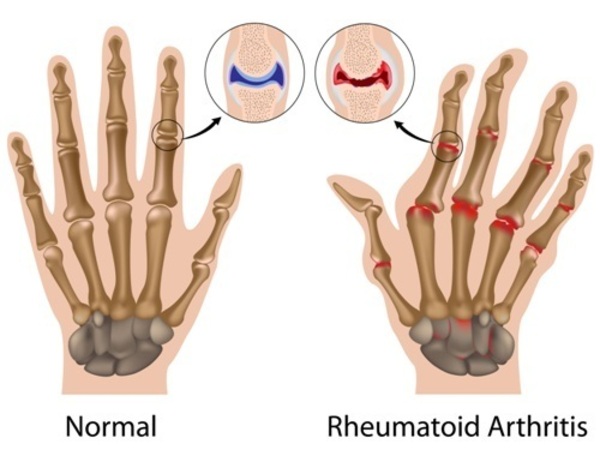

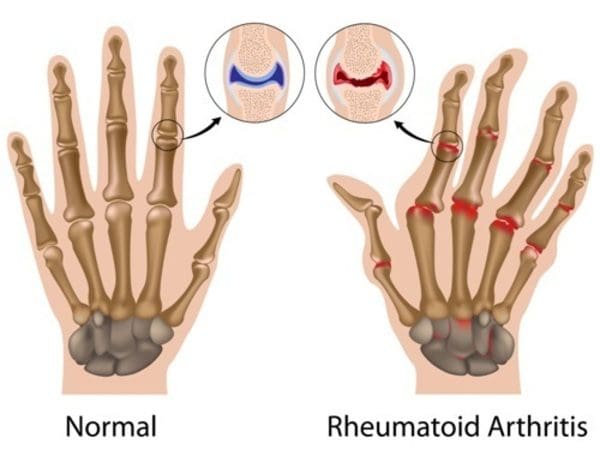

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

Rheumatoid arthritis is when the immune system is attacking the joints. This attack causes redness, warmth, soreness, and stiffness. It�s one of the most common autoimmune diseases that is found in women but can affect men and elderly people as well. Studies have shown that if a family member has rheumatoid arthritis, it is likely that other family members may have an increased chance of developing this autoimmune disease. The signs and symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis can vary depending on the severity of the inflamed joints, potentially causing them to deform and shift out of place.��

Lupus

Lupus is a systemic autoimmune disease that occurs when an individual�s immune system starts attacking their own tissue and organs. Even though lupus is difficult to diagnose because it often mimics other ailments, it can cause inflammation to different body systems. These body systems include the joints, skin, kidneys, blood cells, brain, heart, and lungs. A distinctive sign of lupus is a facial rash that resembles butterfly wings unfolding across booth cheek.

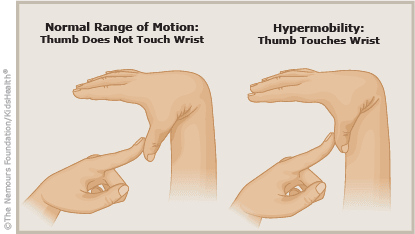

Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS)

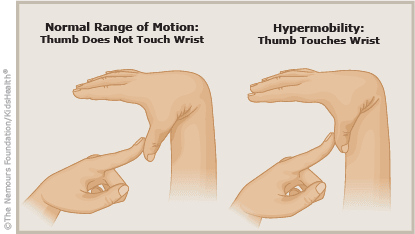

EDS (Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome) is a rare autoimmune disease that causes soft connective tissues to be fragile in the body. This autoimmune disease is still new for doctors; however, there is always more research to be done about this disease. The symptoms can vary from mild skin and joint hyperlaxity to severe physical disability and life-threatening vascular complications. One of the most common symptoms is joint hypermobility. This disease can cause the joints to be unstable or loose, and it can cause the body�s joints to have frequent dislocations and pain.

Polymyalgia Rheumatica

Polymyalgia rheumatica is an inflammatory musculoskeletal disorder that is most common in elderly adults. This disease causes muscle pain and stiffness around the joints, most commonly occurring in the morning.�It also shares similarities with another disease known as giant cell arteritis. If an individual has polymyalgia rheumatica, they can have the symptoms of giant cell arteritis as well. The symptoms are inflammation in the lining of the arteries. The two factors that can cause the development of polymyalgia rheumatica are genetics and environmental exposure that can increase the chances of having the disorder.

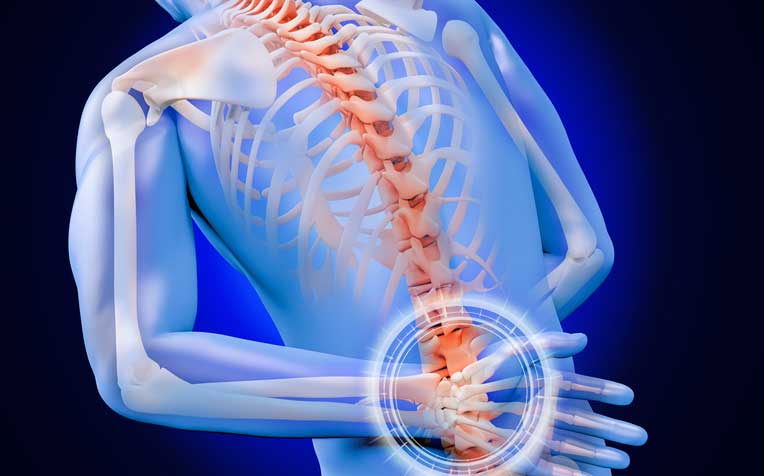

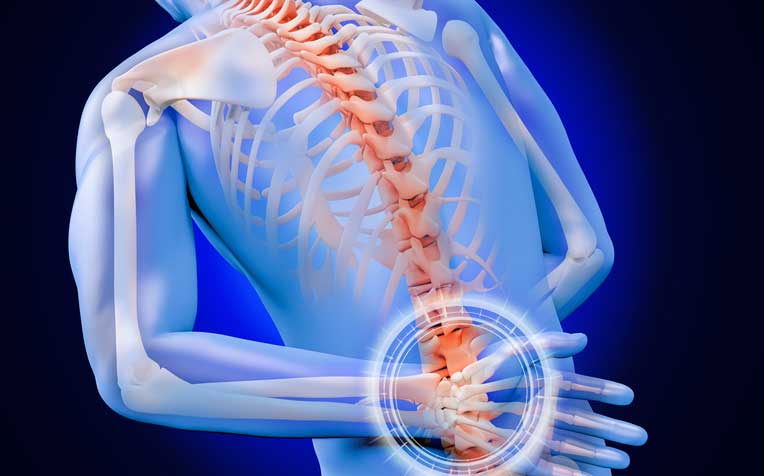

Ankylosing spondylitis

Ankylosing spondylitis is an autoimmune inflammatory disease that can cause some of the vertebrae in the spine to fuse over time. When this happens, the fusing makes the spine less flexible and causes the body to be in a hunched-forward posture. It is most common for men, and there are treatments to lessen the symptoms and possibly slow down the progression of the disease.

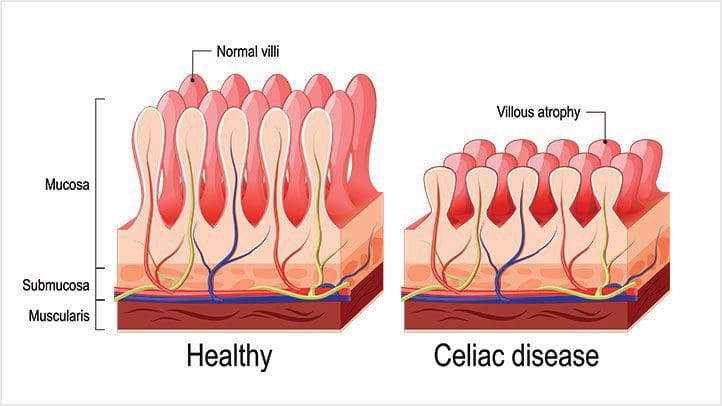

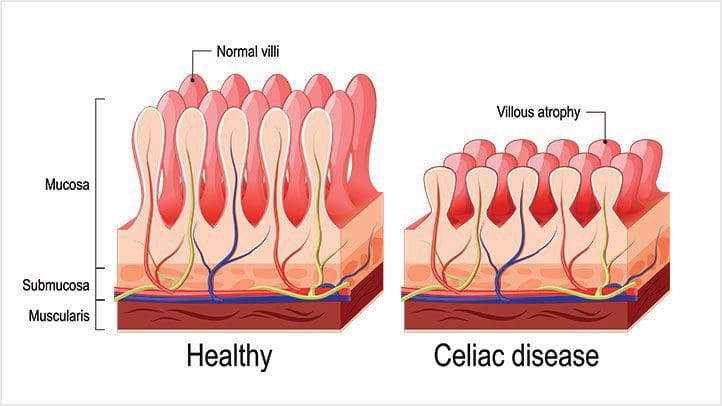

Celiac disease

Celiac disease is an autoimmune disease that occurs in about 1% of individuals. This disease makes the individual have an inflammatory reaction to the intestinal permeability barrier from eating gluten found in wheat, rye, and barley. Studies show that patients with celiac disease and autoimmune disease have to be on a gluten-free diet to heal the gut. Symptoms can include bloating, digestive issues, inflammation, and skin rashes.

Conclusion

Mechanisms of an autoimmune disease can be caused by genetics or induced by environmental factors. This can cause an individual to have problems in their body related to inflammation.�There are many autoimmune diseases�that can affect the body from the most common to some of the rarer kinds and it can have lasting effects.

In honor of Governor Abbott’s declaration, October is Chiropractic Health Month. To learn more about the proposal on our website.

The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal, and nervous health issues as well as functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions. We use functional health protocols to treat injuries or chronic disorders of the musculoskeletal system. To further discuss the subject matter above, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

References:

Anaya, Juan-Manuel, et al. �The Autoimmune Ecology.� Frontiers in Immunology, Frontiers Media S.A., 26 Apr. 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4844615/.

Bonds, Rana S, et al. �A Structural Basis for Food Allergy: the Role of Cross-Reactivity.� Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Feb. 2008, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18188023.

Clinic Staff, Mayo. �Ankylosing Spondylitis.� Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 7 Mar. 2018, www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/ankylosing-spondylitis/symptoms-causes/syc-20354808.

Clinic Staff, Mayo. �Lupus.� Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 25 Oct. 2017, www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/lupus/symptoms-causes/syc-20365789.

Clinic Staff, Mayo. �Polymyalgia Rheumatica.� Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 23 June 2018, www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/polymyalgia-rheumatica/symptoms-causes/syc-20376539.

Cusick, Matthew F, et al. �Molecular Mimicry as a Mechanism of Autoimmune Disease.� Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Feb. 2012, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3266166/.

De Paepe, A, and F Malfait. �The Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, a Disorder with Many Faces.� Clinical Genetics, U.S. National Library of Medicine, July 2012, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22353005.

Schmidt, Zsuzsa, and Gyula Po�r. �Polymyalgia Rheumatica Update, 2015.� Orvosi Hetilap, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 3 Jan. 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26708681.

Scott, David L, et al. �Rheumatoid Arthritis.� Lancet (London, England), U.S. National Library of Medicine, 25 Sept. 2010, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20870100.

Vojdani, Aristo, et al. �Environmental Triggers and Autoimmunity.� Autoimmune Diseases, Hindawi Publishing Corporation, 2014, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4290643/.

Watson, Stephanie. �Autoimmune Diseases: Types, Symptoms, Causes, Diagnosis & More.� Healthline, Healthline Media, 26 Mar. 2019, www.healthline.com/health/autoimmune-disorders.

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Functional Medicine, Gut and Intestinal Health, Health, Wellness

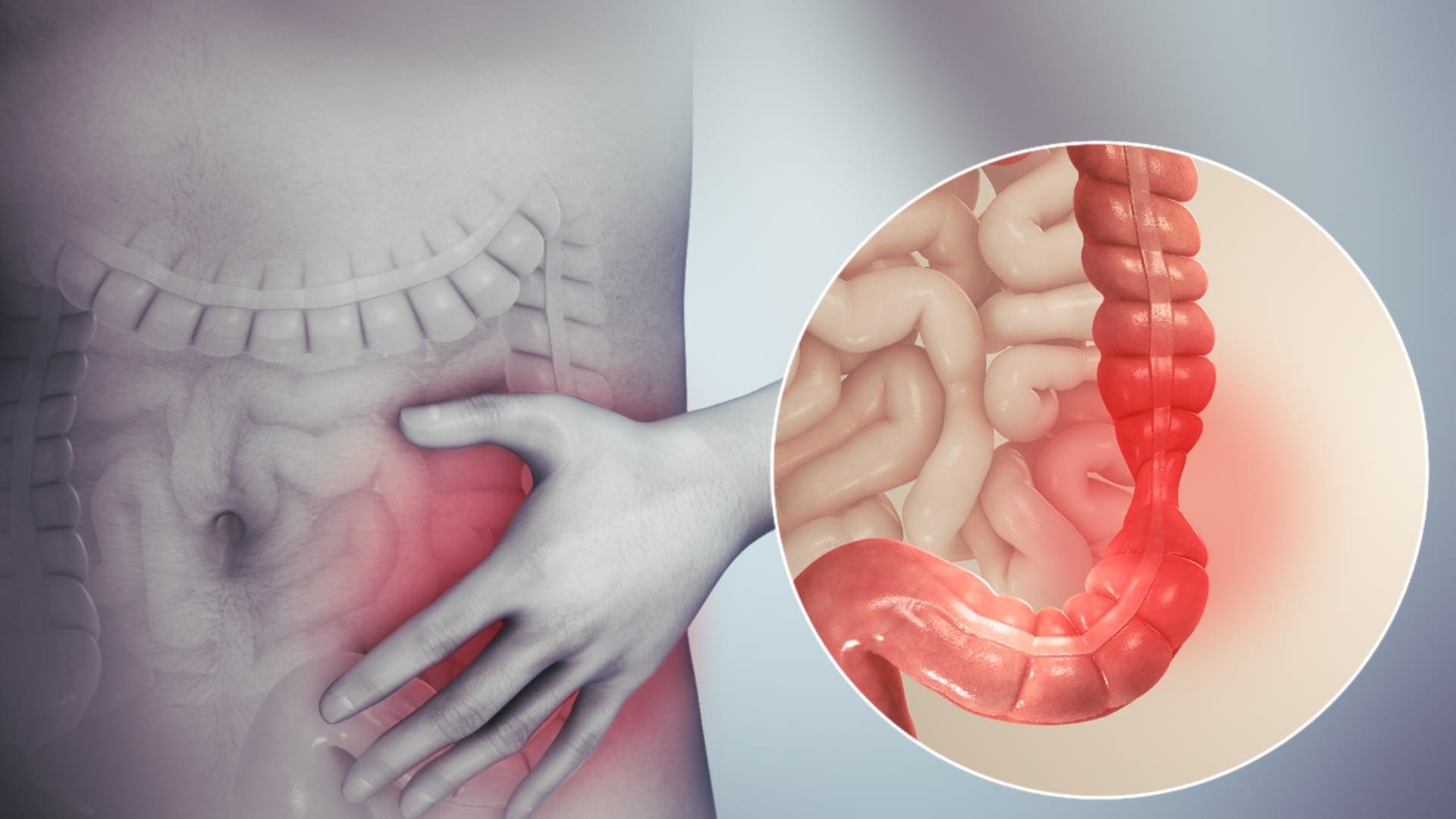

SIBO (small intestinal bacterial overgrowth) is defined as 105 up to 106 organisms of bacteria in the small intestines. It is highly relevant to remember that the abundance of bacteria in the small intestine that has SIBO, are healthy bacteria that live in the gastrointestinal tract. It means that the bacteria in the digestive tract is either missed or dislocated and is in the wrong place in the small intestines. While SIBO still remains a poorly understood disease, it is frequently implicated to be the cause of chronic diarrhea and malabsorption. Individuals who have SIBO can also suffer from many chronic illnesses. This includes unintended weight loss, nutritional deficiencies, and osteoporosis.

SIBO and IBS

Studies have indicated that 84% of individuals that has IBS (irritable bowel syndrome) will have SIBO. SIBO is one of the causes of leaky gut, and leaky gut is one of the triad factors that can lead the body to have an autoimmune disease. Health care professionals that diagnose individuals who have SIBO can link the virus to other health problems that the individual may have. Studies have mentioned that when LPS (lipopolysaccharide) is moving from the large intestines to the small intestines, it can contribute to developing intestinal inflammation. With LPS, it can cause an increase of intestinal tight junction permeability or leaky gut.

So SIBO will release LPS into the gut, causing the leaky gut to the gut system in the body. Another study showed that autoimmune diseases are always a triad of a few different things. To have an autoimmune disease, you have to have the gene to get the disease. Although most people know that if they have a gene, doesn�t mean that they will have an autoimmune disease. Even if they don�t have an autoimmune disease, there�s an environmental trigger that will come on and creates an epigenetic change. This will cause the gene in the human body to be expressed.

So the first two factors of the autoimmune disease, are a genetic factor and an environmental factor, the third and final factor is intestinal permeability. So if the primary two factors that are causing disruption to the intestinal permeability, they will prevent the intestinal permeability to actually heal itself. With all three elements being linked to autoimmune disease and SIBO, it will cause the body to have the leaky gut syndrome and health problems to individuals.

So when doctors are diagnosing the patient that has SIBO, they will do a lactulose breath test. What this test does, is that it will indicate that the patient has IBS bloating, and it is causing them discomfort in their gut. Research stated that the lactulose breath test shows the correlation between the pattern of the bowel movements and the type of excreted gas in the stomach. So for anyone that is positive with IBS and takes the breath test, they will understand the consequences of the factors that are leading to the SIBO disease and causing leaky gut.

How do we get SIBO?

With the understanding of what SIBO is, we can see that SIBO is not the only cause of irritable bowel syndrome, but the big player of the syndrome. So taking a step back, we have to discuss what the MMG (Migrating Motor Complex) is before we go further in explaining the pathogenesis of the SIBO disease. Migrating motor complexes are waves of electrical activity that is sweeping through the intestines in a regular cycle. It often happens when a person is fasting, therefore with MMG, we can look at the acute gastroenteritis in the body.

With acute gastroenteritis, the body has some sort of severe infection like bloating, diarrhea, constipation, or a variety of things that are infectious to the gut; however, they are self-limiting. Healthcare professionals who see patients with these acute infections can see that most of the bacteria can cause gastroenteritis, pile up, and release CTD (cytolethal distending toxin). What CTD does is that it will create a reaction against vinculin; which regulates the ICC (interstitial cells of Cajal) and the ICC then regulates the migrating motor complex.

So when the CTD releases toxins in the gut, it causes a reaction to a molecular mimicry reaction. That reaction causes the body to create antibodies to fight against that toxin but through molecular mimicry. CTD looks exactly like vinculin and cross-reacts with the antibodies, So now those antibodies are attacking vinculin, thus damaging the ICC. Since the MMC clears the intestinal tract, when a person is fasting, and the CTD is damaging the intestines, SIBO is created since the body can not flush out the bacteria.

Studies have shown that there are many ways to get SIBO, it can happen by either food poisoning, abdominal surgery, or low stomach acid. Another thing to mention is that mostly 70% of SIBO is caused by food poisoning. Most people who had to suffer from food poisoning don�t realize that SIBO is already in their gut. So the research states that small bowel motility disorders can be the predispose development of SIBO since the bacteria may not be effectively swept from the bowel into to colon.

Treating SIBO

There are many ways to treat SIBO, healthcare professionals can suggest these treatments to their patients who have SIBO and start restoring their intestinal barrier in the long haul. So here are some of the procedures that can help the body and treat SIBO.

- Pharmaceuticals: If a patient has constipation and is taking rifaximin if the symptoms are not clearing up, adding another medication with rifaximin for 14 days may help in battling SIBO. It will take a bit longer, but it will help clear the SIBO out of the gut.

- Herbal Treatment: With herbal treatments, there are many ways to help treat SIBO naturally. It can be berberine containing herbs, oil of oregano, neem, garlic, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lauricidin, and Antrantil. These herbal treatments can naturally help to fight against SIBO, and studies show that 46% of patients feel a lot better in a short amount of time.

Conclusion

So SIBO is a bacterial disease that can disrupt the gastrointestinal tract and cause the leaky gut to the body. It will cause inflammation and can be in an individual�s body through three factors like genetics, environmental triggers, and food poisoning. It can be treated through pharmaceuticals and herbal treatments prescribed by doctors.� In honor of Governor Abbott’s proclamation, October is Chiropractic Health Month, learn more about this proposal on our website and read what the proposal is all about. The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal, and nervous health issues as well as functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions. We use functional health protocols to treat injuries or chronic disorders of the musculoskeletal system. To further discuss the subject matter above, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

References:

Bezine, Elisabeth, et al. �The Cytolethal Distending Toxin Effects on Mammalian Cells: a DNA Damage Perspective.� Cells, MDPI, 11 June 2014, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4092857/.

Brown, Kenneth, et al. �Response of Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Constipation Patients Administered a Combined Quebracho/Conker Tree/M. Balsamea Willd Extract.� World Journal of Gastrointestinal Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Baishideng Publishing Group Inc, 6 Aug. 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4986399/.

Chedid, Victor, et al. �Herbal Therapy Is Equivalent to Rifaximin for the Treatment of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth.� Global Advances in Health and Medicine, Global Advances in Health and Medicine, May 2014, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4030608/.

Dukowicz, Andrew C, et al. �Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: a Comprehensive Review.� Gastroenterology & Hepatology, Millennium Medical Publishing, Feb. 2007, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3099351/.

Endo, EH, and Dias Filho. �Antibacterial Activity of Berberine against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Planktonic and Biofilm Cells.� Austin Journal of Tropical Medicine & Hygiene, 19 Feb. 2015, austinpublishinggroup.com/tropical-medicine/fulltext/ajtmh-v1-id1005.php.

Fasano, Alessio, and Terez Shea-Donohue. �Mechanisms of Disease: the Role of Intestinal Barrier Function in the Pathogenesis of Gastrointestinal Autoimmune Diseases.� Nature News, Nature Publishing Group, 1 Sept. 2005, www.nature.com/articles/ncpgasthep0259.

Ghonmode, Wasudeo Namdeo, et al. �Comparison of the Antibacterial Efficiency of Neem Leaf Extracts, Grape Seed Extracts and 3% Sodium Hypochlorite against E. Feacalis – An in Vitro Study.� Journal of International Oral Health: JIOH, International Society of Preventive and Community Dentistry, Dec. 2013, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24453446.

Guo, Shuhong, et al. �Lipopolysaccharide Regulation of Intestinal Tight Junction Permeability Is Mediated by TLR4 Signal Transduction Pathway Activation of FAK and MyD88.� Journal of Immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950), U.S. National Library of Medicine, 15 Nov. 2015, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26466961.

Lin, Henry C. �Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: a Framework for Understanding Irritable Bowel Syndrome.� JAMA, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 18 Aug. 2004, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15316000.

Preuss, Harry G, et al. �Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations of Herbal Essential Oils and Monolaurin for Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria.� Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Apr. 2005, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16010969.

Sienkiewicz, Monika, et al. �The Antibacterial Activity of Oregano Essential Oil (Origanum Heracleoticum L.) against Clinical Strains of Escherichia Coli and Pseudomonas Aeruginosa.� Medycyna Doswiadczalna i Mikrobiologia, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2012, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23484421.

Soifer, Luis Oscar, et al. �Comparative Clinical Efficacy of a Probiotic vs. an Antibiotic in the Treatment of Patients with Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth and Chronic Abdominal Functional Distension: a Pilot Study.� Acta Gastroenterologica Latinoamericana, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Dec. 2010, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21381407/.

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Functional Medicine, Health, Integrative Functional Wellness, Wellness

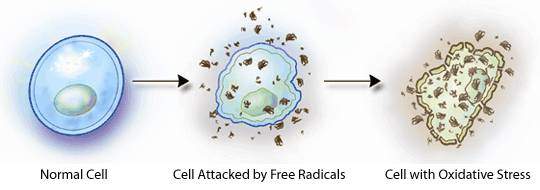

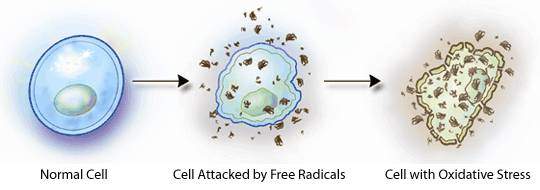

The Nrf2 cell defense creates a pathway that provides protection against oxidative stress and disorders. It plays a vital role in maintaining cellular homeostasis and keeping each cell strand in check. Without the Nrf2 cell defense, oxidative stress can be excessive and directly cause or contribute to many common diseases. This includes cancer, osteoporosis, inflammatory bowel diseases, and neurodegeneration. Studies show that even oxidative stress can contribute to insulin resistance and multiple sclerosis.

Certain foods that are beneficial to the Nrf2 cell structure, due to their antioxidative properties; can enhance the Nrf2 cell gene gradually. Researchers studied that dietary sources that contain antioxidants flavonoids, fermented food and drinks that contain lactobacilli, and sulforaphane from cruciferous vegetables; are the contributors to aid the Nrf2 cell structure. With these certain foods in a person�s diet, it can be beneficial to combating oxidative stress and preventing oxygen toxicity from producing in the bloodstream.

Food That Helps the Nrf2 Cell

Here are some of the foods that contain nutrients to help out the Nrf2 cell:

- Fruits: Red, blue and purple berries, red and purple grapes, apples, citrus fruits and juices (oranges, grapefruits, and lemons)

- Red wine

- Teas: Green, white, black, and oolong

- Chocolate

- Vegetables: Yellow onion, scallions, kale, broccoli, celery, hot peppers, greens beans

- Herbs: Parsley, thyme

- Legumes: Soybeans and other soy products, chickpeas, mung beans

With these types of antioxidant foods, they can help aid the body by lowering the stress compound naturally without the usage of medications. There are ways to get the nutrients of the different food groups to support the body and activate the Nrf2 pathways. Fermented foods that contain lactobacilli can express and activate the gene pathway.

Let�s start with Lactobacillus plantarum and Lactobacillus brevis. These two are the good bacteria that are found in traditional vegetables, fruit, and fermented malt whiskey. They help the body by breaking down the food that is being consumed, absorbing the nutrients, and fighting off the harmful organisms that are causing discomfort to the gut. When these two bacteria are expressing PAD (phenolic acid derivatives) and being introduced to a caffeic acid; the results are astonishing.

Studies indicate that particular strains of lactobacilli can biotransform the caffeic acid to potently activate the Nrf2 pathways from an inactive precursor. �So let�s say that if an individual is stressed and then they eat some food. Suddenly they feel a bit better after eating, that is because of the Nrf2 pathways mixed with the enhanced lactobacilli in their food helped neutralized the stress compound in the body.

With sulforaphane in cruciferous vegetables, it can help with the Nrf2 pathways. Since cruciferous plants have natural fighting properties against cancer, they have a good source of phytonutrients and the sulforaphane combined.

Here are some of the cruciferous vegetables that can help the Nrf2 pathway in the body.

- Arugula

- Bok choy

- Broccoli

- Brussels sprouts

- Cabbage

- Cauliflower

- Kale

- Radish

- Turnips

These vegetables are nutritious when they are eaten raw or cooked. Sulforaphane in the many cruciferous plants has been linked to many health benefits such as improving heart health and digestion. This compound has an inactive form of glucoraphanin, but when it comes in contact with myrosinase, it releases the glucosinolates. This means that when the cruciferous vegetables are either damaged, cut, chopped or chewed on, the myrosinase enzymes are activated and turning into sulforaphane.

Studies have even been shown that sulforaphane can prevent cancer cell growth by releasing antioxidants and detoxifying enzymes that protect carcinogens, which are substances that can cause cancer.

How the Nrf2 Cell Activates

The various molecules in them can exhibit a robust activation in the Nrf2 defense system. Researchers have studied that the Nrf2 defense pathway can provide natural protection against oxidative stress and chemical toxicity through relatively small electrochemical co-factors called Nrf2 activators.

These activators actually amplify the effect of ROS (reactive oxygen species) by cycling through oxidation-reduction reactions and liberating Nrf2 in the human endothelial cells. Since the human body can get sick from stress, it is essential to eat foods that can fight off the harmful organisms. Nrf2 cells do regulate the oxidative stress by releasing itself into the body�s system. It is crucial to make sure that good, nutritious food that is beneficial in helping the Nrf2 cells by doing it naturally.

With a person�s hectic lifestyle gets in the way, they start to feel overly stressed. The body begins to develop chronic ailments that can harm not only the outside of the body but the inside as well. When individuals go to see health care professional for any chronic diseases that they may have, they will be informed of remedies to help aid them the best way they can. Individuals can find ways to deal with the stress hormone and calm it down through functional medicine. So when the body develops oxidative stress, it will affect the organ system, the nerve system, and the neurological system.

With the Nrf2 cells, the cell structure goes towards the oxidative stress compound and put a stop to it. And with the nutritious food that is available to aid the Nrf2 cell more. When we can calm down our anxious mind through the use of functional medicine and by eating healthy, organic, whole foods; we are actually repairing the body from the inside out.

Conclusion

As stated from the beginning, the Nrf2 cell helps the body by protecting it against oxidative stress. When we add nutritious food into the collection, it is aiding the Nrf2 cells a whole lot. Since the entire body needs the nutrients from the different food groups to assist not only the Nrf2 cells but to all crucial organs that need the nutrient sources to function correctly. The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal, and nervous health issues as well as functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions. We use functional health protocols to treat injuries or chronic disorders of the musculoskeletal system. To further discuss the subject matter above, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

References

Bryan, Holly K, et al. �The Nrf2 Cell Defence Pathway: Keap1-Dependent and -Independent Mechanisms of Regulation.� Biochemical Pharmacology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 15 Mar. 2013, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23219527.

Coyle, Daisy. �Sulforaphane: Benefits, Side Effects, and Food Sources.� Healthline, 26 Feb. 2019, www.healthline.com/nutrition/sulforaphane.

Prochaska, H J, et al. �On the Mechanisms of Induction of cancer-protective Enzymes: a Unifying Proposal.� Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Dec. 1985, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3934671.

Senger, Donald R., et al. �Activation of the Nrf2 Cell Defense Pathway by Ancient Foods: Disease Prevention by Important Molecules and Microbes Lost from the Modern Western Diet.� PLOS ONE, Public Library of Science, 17 Feb. 2016, journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0148042.

Shaw, Pamela. �The Nrf2 Diet.� ALS Worldwide, 27 Jan. 2015, alsworldwide.org/care-and-support/article/the-nrf2-diet.

Su, Xuling, et al. �Anticancer Activity of Sulforaphane: The Epigenetic Mechanisms and the Nrf2 Signaling Pathway.� Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, Hindawi, 6 June 2018, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29977456.

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Chiropractic, Functional Medicine, Health, Hormone Balance, Integrative Functional Wellness, Wellness

Hormone testing can now be done by using top of the line integrative methods and techniques. There are multiple reasons and benefits for an individual to complete a hormone test. These tests have the ability to help a patient understand their cycle, testosterone/ estrogen levels, why they are tired upon waking or throughout their day, and more.

Precision Analyical, Inc. has discovered a way to use scientists who have extensive experience and coupled them with the most advanced analytical methods and instruments. This allows them to achieve the best results when it comes to the dutchtest.

What is D.U.T.C.H?

D.U.T.C.H stands for ” Dried Urine for Comprehensive Hormones” and is comprised of multiple tests designed by Precision Analytical Inc. Dried urine samples allow scientists to see an entire day of hormones and measure multiple different aspects. There are different D.U.T.C.H tests that can be completed depending on the patient’s needs.�

- Dutch Complete– This is a comprehensive assessment of sex and adrenal hormones and their metabolites. This test measures progesterone, androgen, estrogen metabolites, cortisol, cortisone, cortisol metabolites, creatine, DHEA-S.�

- Dutch Sex and Hormone Metabolites– This test is focused on testing progesterone, androgen, estrogen metabolites

- Dutch Adrenal– This is important to measure because it controls the stress hormone and the levels in the body to help with energy upon waking. This test specifically measures cortisol, cortisol metabolites, creatinine, DHEA-S

- Dutch OATS “Organic Acid Tests”-� This test will give insights to symptoms such as mood and fatigue. This test measures 9-OHdG, melatonin.

- Dutch Plus– This test uses 5 saliva samples to provide the up and down pattern of cortisol and cortisone throughout the day. This test adds salivary cortisol measurements of the cortisol awakening response (CAR) to the dutch complete to bring another important piece of the HPA axis into focus

- Dutch Test Cycle Mapping– This test maps the progesterone and estrogen pattern throughout the menstrual cycle. It provides the full picture of a woman’s cycle to answer important questions for patients with month-long symptoms, infertility, and PCOS. This test is targeted to measure 9 estrogens and progesterone that are taken throughout the cycle to characterize the follicular, ovulatory, and luteal phases.�

How Does It Work?

One of the reasons that many practicing offices are starting to use the D.U.T.C.H tests is because they have an extremely simple sample collection. Patients will collect just 4-5 dried urine samples over a period of 24 hours. This makes transportation and collection of the sample hassle-free. The dried urine samples provide excellent results due to the fact that the collections offer a span of the entires day hormones. The time of testing looks as follows:

- The patient obtains the first sample at approximately 5pm ( dinnertime)

- The� second sample is to be taken around 10 pm ( bedtime)

- This next sample is dependent upon each individual, but if the patient wakes to urinate during the night, a sample is to be collected at this time.

- The third sample should be collected within 10 minutes of rising. It is very important that the patient does not lay in bed after waking and they collect this sample within those allotted 10 minute time frame.

- Once the patient has collected their third sample upon rising, they should set an alarm for 2 hours, as this is when the fourth and final sample is to be collected.

As one can see above, these urine samples will be dry when sent off to the lab. Studies show that dried urine samples are stable for weeks and will give an accurate representation of the hormone levels that are being assessed. From here, the results are gone over with a team of clinicians from Precision Analytical with the doctor who ordered the test. This ensures that the best treatment protocol is created for the patient.��

What Is The Purpose?�

With the turn around time being just 7-10 business days, individuals can gain control fairly quickly. As mentioned, Precision Analytical uses the most advanced instruments to achieve the best results for patients. The main purpose is to create an understanding of what is going on inside the patient’s body and allows the treatment to be more specific and targeted to the individual’s needs. As Chiropractic Health Month approaches, there is no better time than now to get started!�

�I highly recommend the D.U.T.C.H test. Knowing and understanding your hormones and the times that they are rising and falling throughout the day opens so many doors. It allows an individual to have an understanding of why they are so tired or why they can not fall asleep and take distinctive steps towards correcting that issue, rather than shooting in the dark. In addition, it allows patients to have knowledge of what is occurring when it comes to their sex hormone metabolites. This test gives the ordering doctor a complete look at the patient’s hormones and ensures they can be confident in creating a treatment protocol. – Kenna Vaughn, Senior Health Coach

The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal and nervous health issues as well as functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions. We use functional health protocols to treat injuries or chronic disorders of the musculoskeletal system. To further discuss the subject matter above, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .