1. Sarafidis, P.A.; Nilsson, P.M. The metabolic syndrome: A glance at its history. J. Hypertens. 2006, 24, 621�626.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

2. Alberti, K.G.; Zimmet, P.Z. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications.

Part 1: Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation.

Diabet. Med. 1998, 15, 539�553. [CrossRef]

3. Balkau, B.; Charles, M.A. Comment on the provisional report from the WHO consultation. European Group

for the Study of Insulin Resistance (EGIR). Diabet. Med. 1999, 16, 442�423. [PubMed]

4. Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive

Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on

Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA

2001, 285, 2486�2497.

5. Grundy, S.M.; Cleeman, J.I.; Daniels, S.R.; Donato, K.A.; Eckel, R.H.; Franklin, B.A.; Gordon, D.J.;

Krauss, R.M.; Savage, P.J.; Smith, S.C., Jr.; et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome:

An American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation

2005, 112, 2735�2752. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

6. Alberti, K.G.; Zimmet, P.; Shaw, J. The metabolic syndrome�A new worldwide definition. Lancet 2005, 366,

1059�1062. [CrossRef]

7. Selassie, M.; Sinha, A.C. The epidemiology and aetiology of obesity: A global challenge. Best Pract. Res.

Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2011, 25, 1�9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

8. WHO, W.H.O. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/es/ (accessed on

4 June 2016).

9. Shimano, H. Novel qualitative aspects of tissue fatty acids related to metabolic regulation: Lessons from

Elovl6 knockout. Prog. Lipid Res. 2012, 51, 267�271. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

10. Bosomworth, N.J. Approach to identifying and managing atherogenic dyslipidemia: A metabolic

consequence of obesity and diabetes. Can. Fam. Phys. 2013, 59, 1169�1180.

11. Vidal-Puig, A. The Metabolic Syndrome and its Complex Pathophysiology. In A Systems Biology Approach to

Study Metabolic Syndrome; Oresic, M., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 3�16.

12. Poitout, V.; Robertson, R.P. Glucolipotoxicity: Fuel excess and beta-cell dysfunction. Endocr. Rev. 2008, 29,

351�366. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

13. Rizza, W.; Veronese, N.; Fontana, L. What are the roles of calorie restriction and diet quality in promoting

healthy longevity? Ageing Res. Rev. 2014, 13, 38�45. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

14. Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; Levy, D. Epidemiology of Hypertension. In Hypertension: A Companion to Braunwald�s

Heart Disease; Black, H.R., Elliott, W.J., Eds.; Elsevier: Philadephia, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 1�11.

15. Zanchetti, A. Challenges in hypertension: Prevalence, definition, mechanisms and management. J. Hypertens.

2014, 32, 451�453. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

16. Thomas, G.; Shishehbor, M.; Brill, D.; Nally, J.V., Jr. New hypertension guidelines: One size fits most?

Clevel. Clin. J. Med. 2014, 81, 178�188. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

17. James, P.A.; Oparil, S.; Carter, B.L.; Cushman, W.C.; Dennison-Himmelfarb, C.; Handler, J.; Lackland, D.T.;

LeFevre, M.L.; MacKenzie, T.D.; Ogedegbe, O.; et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management

of high blood pressure in adults: Report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National

Committee (JNC 8). JAMA 2014, 311, 507�520. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

18. Klandorf, H.; Chirra, A.R.; DeGruccio, A.; Girman, D.J. Dimethyl sulfoxide modulation of diabetes onset in

NOD mice. Diabetes 1989, 38, 194�197. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

19. Ballard, K.D.; Mah, E.; Guo, Y.; Pei, R.; Volek, J.S.; Bruno, R.S. Low-fat milk ingestion prevents postprandial

hyperglycemia-mediated impairments in vascular endothelial function in obese individuals with metabolic

syndrome. J. Nutr. 2013, 143, 1602�1610. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

20. Pugliese, G.; Solini, A.; Bonora, E.; Orsi, E.; Zerbini, G.; Fondelli, C.; Gruden, G.; Cavalot, F.; Lamacchia, O.;

Trevisan, R.; et al. Distribution of cardiovascular disease and retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes

according to different classification systems for chronic kidney disease: A cross-sectional analysis of the

renal insufficiency and cardiovascular events (RIACE) Italian multicenter study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2014,

13, 59. [PubMed]

21. Asif, M. The prevention and control the type-2 diabetes by changing lifestyle and dietary pattern. J. Educ.

Health Promot. 2014, 3, 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

22. Russell, W.R.; Baka, A.; Bjorck, I.; Delzenne, N.; Gao, D.; Griffiths, H.R.; Hadjilucas, E.; Juvonen, K.;

Lahtinen, S.; Lansink, M.; et al. Impact of Diet Composition on Blood Glucose Regulation. Crit. Rev. Food

Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 541�590. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

23. Soares, R.; Costa, C. Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Angiogenesis in the Metabolic Syndrome; Springer:

Heidelberg, Germany, 2009.

24. Rahal, A.; Kumar, A.; Singh, V.; Yadav, B.; Tiwari, R.; Chakraborty, S.; Dhama, K. Oxidative Stress,

Prooxidants, and Antioxidants: The Interplay. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 761264. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

25. Parthasarathy, S.; Litvinov, D.; Selvarajan, K.; Garelnabi, M. Lipid peroxidation and decomposition�Conflicting

roles in plaque vulnerability and stability. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1781, 221�231. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

26. McGrowder, D.; Riley, C.; Morrison, E.Y.; Gordon, L. The role of high-density lipoproteins in reducing the

risk of vascular diseases, neurogenerative disorders, and cancer. Cholesterol 2011, 2011, 496925. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

27. Ferri, N.; Ruscica, M. Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) and metabolic syndrome:

Insights on insulin resistance, inflammation, and atherogenic dyslipidemia. Endocrine 2016. [CrossRef]

28. Oresic, M.; Vidal-Puig, A. A Systems Biology Approach to Study Metabolic Syndrome; Springer: Heidelberg,

Germany, 2014.

29. Lee, E.G.; Choi, J.H.; Kim, K.E.; Kim, J.H. Effects of a Walking Program on Self-management and Risk Factors

of Metabolic Syndrome in Older Korean Adults. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2014, 26, 105�109. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

30. Bernabe, G.J.; Zafrilla, R.P.; Mulero, C.J.; Gomez, J.P.; Leal, H.M.; Abellan, A.J. Biochemical and nutritional

markers and antioxidant activity in metabolic syndrome. Endocrinol. Nutr. 2013, 61, 302�308.

31. Bales, C.W.; Kraus, W.E. Caloric restriction: Implications for human cardiometabolic health. J. Cardiopulm.

Rehabil. Prev. 2013, 33, 201�208. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

32. Grams, J.; Garvey, W.T. Weight Loss and the Prevention and Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Using Lifestyle

Therapy, Pharmacotherapy, and Bariatric Surgery: Mechanisms of Action. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2015, 4, 287�302.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

33. Lazo, M.; Solga, S.F.; Horska, A.; Bonekamp, S.; Diehl, A.M.; Brancati, F.L.; Wagenknecht, L.E.; Pi-Sunyer, F.X.;

Kahn, S.E.; Clark, J.M. Effect of a 12-month intensive lifestyle intervention on hepatic steatosis in adults with

type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 2156�2163. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

34. Rossmeislova, L.; Malisova, L.; Kracmerova, J.; Stich, V. Adaptation of human adipose tissue to hypocaloric

diet. Int. J. Obes. 2013, 37, 640�650. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

35. Wing, R.R.; Lang, W.; Wadden, T.A.; Safford, M.; Knowler, W.C.; Bertoni, A.G.; Hill, J.O.; Brancati, F.L.;

Peters, A.; Wagenknecht, L. Benefits of modest weight loss in improving cardiovascular risk factors in

overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 1481�1486. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

36. Golay, A.; Brock, E.; Gabriel, R.; Konrad, T.; Lalic, N.; Laville, M.; Mingrone, G.; Petrie, J.; Phan, T.M.;

Pietilainen, K.H.; et al. Taking small steps towards targets�Perspectives for clinical practice in diabetes,

cardiometabolic disorders and beyond. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2013, 67, 322�332. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

37. Fock, K.M.; Khoo, J. Diet and exercise in management of obesity and overweight. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.

2013, 28, 59�63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

38. Abete, I.; Parra, D.; Martinez, J.A. Energy-restricted diets based on a distinct food selection affecting the

glycemic index induce different weight loss and oxidative response. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 27, 545�551. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

39. Alberti, K.G.; Eckel, R.H.; Grundy, S.M.; Zimmet, P.Z.; Cleeman, J.I.; Donato, K.A.; Fruchart, J.C.; James, W.P.;

Loria, C.M.; Smith, S.C., Jr. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: A joint interim statement of the

International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung,

and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis

Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 2009, 120, 1640�1645. [PubMed]

40. Fleming, J.A.; Kris-Etherton, P.M. The evidence for alpha-linolenic acid and cardiovascular disease benefits:

Comparisons with eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid. Adv. Nutr. 2014, 5, 863S�876S. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

41. Gray, B.; Steyn, F.; Davies, P.S.; Vitetta, L. Omega-3 fatty acids: A review of the effects on adiponectin and

leptin and potential implications for obesity management. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 67, 1234�1242. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

42. Wen, Y.T.; Dai, J.H.; Gao, Q. Effects of Omega-3 fatty acid on major cardiovascular events and mortality

in patients with coronary heart disease: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr. Metab.

Cardiovasc. Dis. 2014, 24, 470�475. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

43. Lopez-Huertas, E. The effect of EPA and DHA on metabolic syndrome patients: A systematic review of

randomised controlled trials. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 107, 185�194. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

44. Maiorino, M.I.; Chiodini, P.; Bellastella, G.; Giugliano, D.; Esposito, K. Sexual dysfunction in women with

cancer: A systematic review with meta-analysis of studies using the Female Sexual Function Index. Endocrine

2016, 54, 329�341. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

45. EFSA NDA Panel (EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies). Scientific Opinion on Dietary

Reference Values for fats, including saturated fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, monounsaturated

fatty acids, trans fatty acids, and cholesterol1. EFSA J. 2010, 8, 1461�1566.

46. Bellastella, G.; Bizzarro, A.; Aitella, E.; Barrasso, M.; Cozzolino, D.; di Martino, S.; Esposito, K.; de Bellis, A.

Pregnancy may favour the development of severe autoimmune central diabetes insipidus in women with

vasopressin cell antibodies: Description of two cases. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 172, K11�K17. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

47. Sun, F.H.; Li, C.; Zhang, Y.J.; Wong, S.H.; Wang, L. Effect of Glycemic Index of Breakfast on Energy Intake at

Subsequent Meal among Healthy People: A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2016, 8, 37. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

48. Barclay, A.W.; Brand-Miller, J.C.; Wolever, T.M. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and glycemic response are

not the same. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 1839�1840. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

49. Nakagawa, T.; Hu, H.; Zharikov, S.; Tuttle, K.R.; Short, R.A.; Glushakova, O.; Ouyang, X.; Feig, D.I.;

Block, E.R.; Herrera-Acosta, J.; et al. A causal role for uric acid in fructose-induced metabolic syndrome.

Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2006, 290, F625�F631. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

50. Symons Downs, D.; Hausenblas, H.A. Women�s exercise beliefs and behaviors during their pregnancy and

postpartum. J. Midwifery Women Health 2004, 49, 138�144.

51. Brand-Miller, J.; McMillan-Price, J.; Steinbeck, K.; Caterson, I. Dietary glycemic index: Health implications.

J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2009, 28, 446S�449S. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

52. Thomas, D.; Elliott, E.J. Low glycaemic index, or low glycaemic load, diets for diabetes mellitus.

Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009. [CrossRef]

53. Barrea, L.; Balato, N.; di Somma, C.; Macchia, P.E.; Napolitano, M.; Savanelli, M.C.; Esposito, K.; Colao, A.;

Savastano, S. Nutrition and psoriasis: Is there any association between the severity of the disease and

adherence to the Mediterranean diet? J. Transl. Med. 2015, 13, 18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

54. Mathias, K.C.; Ng, S.W.; Popkin, B. Monitoring changes in the nutritional content of ready-to-eat grain-based

dessert products manufactured and purchased between 2005 and 2012. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 360�368.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

55. Serafini, M.; del Rio, D. Understanding the association between dietary antioxidants, redox status and

disease: Is the Total Antioxidant Capacity the right tool? Redox Rep. 2004, 9, 145�152. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

56. Bellastella, G.; Maiorino, M.I.; Olita, L.; della Volpe, E.; Giugliano, D.; Esposito, K. Premature ejaculation is

associated with glycemic control in Type 1 diabetes. J. Sex. Med. 2015, 12, 93�99. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

57. Zulet, M.A.; Moreno-Aliaga, M.J.; Martinez, J.A. Dietary Determinants of Fat Mass and Body Composition.

In Adipose Tissue Biology; Symonds, M.E., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 271�315.

58. Carlsen, M.H.; Halvorsen, B.L.; Holte, K.; Bohn, S.K.; Dragland, S.; Sampson, L.; Willey, C.; Senoo, H.;

Umezono, Y.; Sanada, C.; et al. The total antioxidant content of more than 3100 foods, beverages, spices,

herbs and supplements used worldwide. Nutr. J. 2010, 9, 3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

59. Harasym, J.; Oledzki, R. Effect of fruit and vegetable antioxidants on total antioxidant capacity of blood

plasma. Nutrition 2014, 30, 511�517. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

60. Maiorino, M.I.; Bellastella, G.; Petrizzo, M.; della Volpe, E.; Orlando, R.; Giugliano, D.; Esposito, K. Circulating

endothelial progenitor cells in type 1 diabetic patients with erectile dysfunction. Endocrine 2015, 49, 415�421.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

61. Bahadoran, Z.; Golzarand, M.; Mirmiran, P.; Shiva, N.; Azizi, F. Dietary total antioxidant capacity and the

occurrence of metabolic syndrome and its components after a 3-year follow-up in adults: Tehran Lipid and

Glucose Study. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 9, 70. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

62. Chrysohoou, C.; Esposito, K.; Giugliano, D.; Panagiotakos, D.B. Peripheral Arterial Disease and

Cardiovascular Risk: The Role of Mediterranean Diet. Angiology 2015, 66, 708�710. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

63. De la Iglesia, R.; Lopez-Legarrea, P.; Celada, P.; Sanchez-Muniz, F.J.; Martinez, J.A.; Zulet, M.A. Beneficial

effects of the RESMENA dietary pattern on oxidative stress in patients suffering from metabolic syndrome

with hyperglycemia are associated to dietary TAC and fruit consumption. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 6903�6919.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

64. Lopez-Legarrea, P.; de la Iglesia, R.; Abete, I.; Bondia-Pons, I.; Navas-Carretero, S.; Forga, L.; Martinez, J.A.;

Zulet, M.A. Short-term role of the dietary total antioxidant capacity in two hypocaloric regimes on obese

with metabolic syndrome symptoms: The RESMENA randomized controlled trial. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 10, 22.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

65. Puchau, B.; Zulet, M.A.; de Echavarri, A.G.; Hermsdorff, H.H.; Martinez, J.A. Dietary total antioxidant

capacity is negatively associated with some metabolic syndrome features in healthy young adults. Nutrition

2010, 26, 534�541. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

66. World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic; Report of a WHO

Consultation; World Health Organization Technical Report Series; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000.

67. Tapsell, L.C.; Hemphill, I.; Cobiac, L.; Patch, C.S.; Sullivan, D.R.; Fenech, M.; Roodenrys, S.; Keogh, J.B.;

Clifton, P.M.; Williams, P.G.; et al. Health benefits of herbs and spices: The past, the present, the future.

Med. J. Aust. 2006, 185, S4�S24. [PubMed]

68. Abete, I.; Astrup, A.; Martinez, J.A.; Thorsdottir, I.; Zulet, M.A. Obesity and the metabolic syndrome: Role of

different dietary macronutrient distribution patterns and specific nutritional components on weight loss and

maintenance. Nutr. Rev. 2010, 68, 214�231. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

69. Ebbeling, C.B.; Swain, J.F.; Feldman, H.A.; Wong, W.W.; Hachey, D.L.; Garcia-Lago, E.; Ludwig, D.S. Effects

of dietary composition on energy expenditure during weight-loss maintenance. JAMA 2012, 307, 2627�2634.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

70. Abete, I.; Goyenechea, E.; Zulet, M.A.; Martinez, J.A. Obesity and metabolic syndrome: Potential benefit

from specific nutritional components. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2011, 21, B1�B15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

71. Arciero, P.J.; Ormsbee, M.J.; Gentile, C.L.; Nindl, B.C.; Brestoff, J.R.; Ruby, M. Increased protein intake and

meal frequency reduces abdominal fat during energy balance and energy deficit. Obesity 2013, 21, 1357�1366.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

72. Wikarek, T.; Chudek, J.; Owczarek, A.; Olszanecka-Glinianowicz, M. Effect of dietary macronutrients on

postprandial incretin hormone release and satiety in obese and normal-weight women. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 111,

236�246. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

73. Bray, G.A.; Smith, S.R.; de Jonge, L.; Xie, H.; Rood, J.; Martin, C.K.; Most, M.; Brock, C.; Mancuso, S.;

Redman, L.M. Effect of dietary protein content on weight gain, energy expenditure, and body composition

during overeating: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2012, 307, 47�55. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

74. Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S.; Nieuwenhuizen, A.; Tome, D.; Soenen, S.; Westerterp, K.R. Dietary protein,

weight loss, and weight maintenance. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2009, 29, 21�41. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

75. Koppes, L.L.; Boon, N.; Nooyens, A.C.; van Mechelen, W.; Saris, W.H. Macronutrient distribution over

a period of 23 years in relation to energy intake and body fatness. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 101, 108�115. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

76. De Jonge, L.; Bray, G.A.; Smith, S.R.; Ryan, D.H.; de Souza, R.J.; Loria, C.M.; Champagne, C.M.;

Williamson, D.A.; Sacks, F.M. Effect of diet composition and weight loss on resting energy expenditure in

the POUNDS LOST study. Obesity 2012, 20, 2384�2389. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

77. Stocks, T.; Angquist, L.; Hager, J.; Charon, C.; Holst, C.; Martinez, J.A.; Saris, W.H.; Astrup, A.; Sorensen, T.I.;

Larsen, L.H. TFAP2B-dietary protein and glycemic index interactions and weight maintenance after weight

loss in the DiOGenes trial. Hum. Hered. 2013, 75, 213�219. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

78. Giugliano, D.; Maiorino, M.I.; Esposito, K. Linking prediabetes and cancer: A complex issue. Diabetologia

2015, 58, 201�202. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

79. Bendtsen, L.Q.; Lorenzen, J.K.; Bendsen, N.T.; Rasmussen, C.; Astrup, A. Effect of dairy proteins on appetite,

energy expenditure, body weight, and composition: A review of the evidence from controlled clinical trials.

Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 418�438. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

80. Heer, M.; Egert, S. Nutrients other than carbohydrates: Their effects on glucose homeostasis in humans.

Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2015, 31, 14�35. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

81. Layman, D.K.; Evans, E.M.; Erickson, D.; Seyler, J.; Weber, J.; Bagshaw, D.; Griel, A.; Psota, T.; Kris-Etherton, P.

A moderate-protein diet produces sustained weight loss and long-term changes in body composition and

blood lipids in obese adults. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 514�521. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

82. Pedersen, A.N.; Kondrup, J.; Borsheim, E. Health effects of protein intake in healthy adults: A systematic

literature review. Food Nutr. Res. 2013, 57, 21245. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

83. Daly, R.M.; O�Connell, S.L.; Mundell, N.L.; Grimes, C.A.; Dunstan, D.W.; Nowson, C.A. Protein-enriched

diet, with the use of lean red meat, combined with progressive resistance training enhances lean tissue mass

and muscle strength and reduces circulating IL-6 concentrations in elderly women: A cluster randomized

controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 99, 899�910. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

84. Arciero, P.J.; Gentile, C.L.; Pressman, R.; Everett, M.; Ormsbee, M.J.; Martin, J.; Santamore, J.; Gorman, L.;

Fehling, P.C.; Vukovich, M.D.; et al. Moderate protein intake improves total and regional body composition

and insulin sensitivity in overweight adults. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2008, 57, 757�765. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

85. Gregory, S.M.; Headley, S.A.; Wood, R.J. Effects of dietary macronutrient distribution on vascular integrity in

obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nutr. Rev. 2011, 69, 509�519. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

86. Consenso FESNAD-SEEDO. Recomendaciones nutricionales basadas en la evidencia para la prevenci�n y el

tratamiento del sobrepeso y la obesidad en adultos (Consenso FESNAD-SEEDO). Rev. Esp. Obes. 2011, 10, 36.

87. Jakubowicz, D.; Froy, O.; Wainstein, J.; Boaz, M. Meal timing and composition influence ghrelin levels,

appetite scores and weight loss maintenance in overweight and obese adults. Steroids 2012, 77, 323�331.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

88. Schwarz, N.A.; Rigby, B.R.; La Bounty, P.; Shelmadine, B.; Bowden, R.G. A review of weight control strategies

and their effects on the regulation of hormonal balance. J. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 2011, 237932. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

89. Ohkawara, K.; Cornier, M.A.; Kohrt, W.M.; Melanson, E.L. Effects of increased meal frequency on fat

oxidation and perceived hunger. Obesity 2013, 21, 336�343. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

90. Ekmekcioglu, C.; Touitou, Y. Chronobiological aspects of food intake and metabolism and their relevance on

energy balance and weight regulation. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, 14�25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

91. Lioret, S.; Touvier, M.; Lafay, L.; Volatier, J.L.; Maire, B. Are eating occasions and their energy content related

to child overweight and socioeconomic status? Obesity 2008, 16, 2518�2523. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

92. Bhutani, S.; Varady, K.A. Nibbling versus feasting: Which meal pattern is better for heart disease prevention?

Nutr. Rev. 2009, 67, 591�598. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

93. Leidy, H.J.; Tang, M.; Armstrong, C.L.; Martin, C.B.; Campbell, W.W. The effects of consuming frequent,

higher protein meals on appetite and satiety during weight loss in overweight/obese men. Obesity 2011, 19,

818�824. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

94. Mills, J.P.; Perry, C.D.; Reicks, M. Eating frequency is associated with energy intake but not obesity in midlife

women. Obesity 2011, 19, 552�559. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

95. Cameron, J.D.; Cyr, M.J.; Doucet, E. Increased meal frequency does not promote greater weight loss in subjects

who were prescribed an 8-week equi-energetic energy-restricted diet. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 103, 1098�1101.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

96. Smeets, A.J.; Lejeune, M.P.; Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S. Effects of oral fat perception by modified sham

feeding on energy expenditure, hormones and appetite profile in the postprandial state. Br. J. Nutr. 2009,

101, 1360�1368. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

97. Taylor, M.A.; Garrow, J.S. Compared with nibbling, neither gorging nor a morning fast affect short-term

energy balance in obese patients in a chamber calorimeter. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 2001, 25, 519�528.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

98. Smeets, A.J.; Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S. Acute effects on metabolism and appetite profile of one meal

difference in the lower range of meal frequency. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 99, 1316�1321. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

99. Heden, T.D.; LeCheminant, J.D.; Smith, J.D. Influence of weight classification on walking and jogging energy

expenditure prediction in women. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2012, 83, 391�399. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

100. Bachman, J.L.; Raynor, H.A. Effects of manipulating eating frequency during a behavioral weight loss

intervention: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Obesity 2012, 20, 985�992. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

101. Perrigue, M.M.; Drewnowski, A.; Wang, C.Y.; Neuhouser, M.L. Higher Eating Frequency Does Not Decrease

Appetite in Healthy Adults. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 59�64. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

102. Keys, A. Coronary heart disease in seven countries. 1970. Nutrition 1997, 13, 249�253. [CrossRef]

103. Keys, A.; Menotti, A.; Aravanis, C.; Blackburn, H.; Djordevic, B.S.; Buzina, R.; Dontas, A.S.; Fidanza, F.;

Karvonen, M.J.; Kimura, N.; et al. The seven countries study: 2289 deaths in 15 years. Prev. Med. 1984, 13,

141�154. [CrossRef]

104. Davis, C.; Bryan, J.; Hodgson, J.; Murphy, K. Definition of the Mediterranean Diet; a Literature Review.

Nutrients 2015, 7, 9139�9153. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

105. Sofi, F.; Macchi, C.; Abbate, R.; Gensini, G.F.; Casini, A. Mediterranean diet and health status: An updated

meta-analysis and a proposal for a literature-based adherence score. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 2769�2782.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

106. Mayneris-Perxachs, J.; Sala-Vila, A.; Chisaguano, M.; Castellote, A.I.; Estruch, R.; Covas, M.I.; Fito, M.;

Salas-Salvado, J.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.; et al. Effects of 1-year intervention with

a Mediterranean diet on plasma fatty acid composition and metabolic syndrome in a population at high

cardiovascular risk. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85202. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

107. Esposito, K.; Maiorino, M.I.; Bellastella, G.; Chiodini, P.; Panagiotakos, D.; Giugliano, D. A journey

into a Mediterranean diet and type 2 diabetes: A systematic review with meta-analyses. BMJ Open

2015, 5, e008222. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

108. Kastorini, C.M.; Milionis, H.J.; Esposito, K.; Giugliano, D.; Goudevenos, J.A.; Panagiotakos, D.B. The effect of

Mediterranean diet on metabolic syndrome and its components: A meta-analysis of 50 studies and 534,906

individuals. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 57, 1299�1313. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

109. Schwingshackl, L.; Missbach, B.; Konig, J.; Hoffmann, G. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and risk of

diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 1292�1299. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

110. Koloverou, E.; Esposito, K.; Giugliano, D.; Panagiotakos, D. The effect of Mediterranean diet on the

development of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis of 10 prospective studies and 136,846 participants.

Metab. Clin. Exp. 2014, 63, 903�911. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

111. Salas-Salvado, J.; Garcia-Arellano, A.; Estruch, R.; Marquez-Sandoval, F.; Corella, D.; Fiol, M.;

Gomez-Gracia, E.; Vinoles, E.; Aros, F.; Herrera, C.; et al. Components of the Mediterranean-type food

pattern and serum inflammatory markers among patients at high risk for cardiovascular disease. Eur. J.

Clin. Nutr. 2008, 62, 651�659. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

112. Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Garcia-Lopez, M.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Toledo, E.; Martinez-Lapiscina, E.H.;

Delgado-Rodriguez, M.; Vazquez, Z.; Benito, S.; Beunza, J.J. Mediterranean diet and the incidence of

cardiovascular disease: A Spanish cohort. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2011, 21, 237�244. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

113. Fito, M.; Estruch, R.; Salas-Salvado, J.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Aros, F.; Vila, J.; Corella, D.; Diaz, O.;

Saez, G.; de la Torre, R.; et al. Effect of the Mediterranean diet on heart failure biomarkers: A randomized

sample from the PREDIMED trial. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2014, 16, 543�550. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

114. Estruch, R.; Ros, E.; Salas-Salvado, J.; Covas, M.I.; Corella, D.; Aros, F.; Gomez-Gracia, E.; Ruiz-Gutierrez, V.;

Fiol, M.; Lapetra, J.; et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. N. Engl.

J. Med. 2013, 368, 1279�1290. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

115. Serra-Majem, L.; Roman, B.; Estruch, R. Scientific evidence of interventions using the Mediterranean diet:

A systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 2006, 64, S27�S47. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

116. Esposito, K.; Kastorini, C.M.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Giugliano, D. Mediterranean diet and weight loss:

Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2011, 9, 1�12. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

117. Razquin, C.; Martinez, J.A.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Mitjavila, M.T.; Estruch, R.; Marti, A. A 3 years

follow-up of a Mediterranean diet rich in virgin olive oil is associated with high plasma antioxidant capacity

and reduced body weight gain. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 63, 1387�1393. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

118. Bertoli, S.; Spadafranca, A.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Ponissi, V.; Beggio, V.; Leone, A.;

Battezzati, A. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet is inversely related to binge eating disorder in patients

seeking a weight loss program. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 34, 107�114. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

119. Rios-Hoyo, A.; Cortes, M.J.; Rios-Ontiveros, H.; Meaney, E.; Ceballos, G.; Gutierrez-Salmean, G. Obesity,

Metabolic Syndrome, and Dietary Therapeutical Approaches with a Special Focus on Nutraceuticals

(Polyphenols): A Mini-Review. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2014, 84, 113�123. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

120. Juraschek, S.P.; Guallar, E.; Appel, L.J.; Miller, E.R., 3rd. Effects of vitamin C supplementation on blood

pressure: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 1079�1088. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

121. Michels, A.J.; Frei, B. Myths, artifacts, and fatal flaws: Identifying limitations and opportunities in vitamin C

research. Nutrients 2013, 5, 5161�5192. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

122. Frei, B.; Birlouez-Aragon, I.; Lykkesfeldt, J. Authors� perspective: What is the optimum intake of vitamin C

in humans? Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2012, 52, 815�829. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

123. Mason, S.A.; della Gatta, P.A.; Snow, R.J.; Russell, A.P.; Wadley, G.D. Ascorbic acid supplementation

improves skeletal muscle oxidative stress and insulin sensitivity in people with type 2 diabetes: Findings of

a randomized controlled study. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 93, 227�238. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

124. Chambial, S.; Dwivedi, S.; Shukla, K.K.; John, P.J.; Sharma, P. Vitamin C in Disease Prevention and Cure:

An Overview. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2013, 28, 314�328. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

125. Block, G.; Jensen, C.D.; Dalvi, T.B.; Norkus, E.P.; Hudes, M.; Crawford, P.B.; Holland, N.; Fung, E.B.;

Schumacher, L.; Harmatz, P. Vitamin C treatment reduces elevated C-reactive protein. Free Radic. Biol. Med.

2009, 46, 70�77. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

126. Ashor, A.W.; Siervo, M.; Lara, J.; Oggioni, C.; Afshar, S.; Mathers, J.C. Effect of vitamin C and vitamin E

supplementation on endothelial function: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled

trials. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 1182�1194. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

127. Kim, S.M.; Lim, S.M.; Yoo, J.A.; Woo, M.J.; Cho, K.H. Consumption of high-dose vitamin C (1250 mg

per day) enhances functional and structural properties of serum lipoprotein to improve anti-oxidant,

anti-atherosclerotic, and anti-aging effects via regulation of anti-inflammatory microRNA. Food Funct.

2015, 6, 3604�3612. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

128. Monfared, S.; Larijani, B.; Abdollahi, M. Islet transplantation and antioxidant management: A comprehensive

review. World J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 15, 1153�1161. [CrossRef]

129. German Nutrition Society (DGE). New Reference Values for Vitamin C Intake. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2015,

67, 13�20.

130. Mamede, A.C.; Tavares, S.D.; Abrantes, A.M.; Trindade, J.; Maia, J.M.; Botelho, M.F. The role of vitamins in

cancer: A review. Nutr. Cancer 2011, 63, 479�494. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

131. Moser, M.A.; Chun, O.K. Vitamin C and Heart Health: A Review Based on Findings from Epidemiologic

Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1328. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

132. Vilaplana-Perez, C.; Aunon, D.; Garcia-Flores, L.A.; Gil-Izquierdo, A. Hydroxytyrosol and potential uses in

cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and AIDS. Front. Nutr. 2014, 1, 18. [PubMed]

133. Achmon, Y.; Fishman, A. The antioxidant hydroxytyrosol: Biotechnological production challenges and

opportunities. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 1119�1130. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

134. Bulotta, S.; Celano, M.; Lepore, S.M.; Montalcini, T.; Pujia, A.; Russo, D. Beneficial effects of the olive

oil phenolic components oleuropein and hydroxytyrosol: Focus on protection against cardiovascular and

metabolic diseases. J. Transl. Med. 2014, 12, 219. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

135. EFSA NDA Panel (EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies). Scientific Opinion on the

substantiation of health claims related to polyphenols in olive and protection of LDL particles from oxidative

damage (ID 1333, 1638, 1639, 1696, 2865), maintenance of normal blood HDL cholesterol concentrations

(ID 1639). EFSA J. 2011, 9, 2033�2058.

136. Scoditti, E.; Nestola, A.; Massaro, M.; Calabriso, N.; Storelli, C.; De Caterina, R.; Carluccio, M.A.

Hydroxytyrosol suppresses MMP-9 and COX-2 activity and expression in activated human monocytes

via PKCalpha and PKCbeta1 inhibition. Atherosclerosis 2014, 232, 17�24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

137. Giordano, E.; Dangles, O.; Rakotomanomana, N.; Baracchini, S.; Visioli, F. 3-O-Hydroxytyrosol glucuronide

and 4-O-hydroxytyrosol glucuronide reduce endoplasmic reticulum stress in vitro. Food Funct. 2015, 6,

3275�3281. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

138. Granados-Principal, S.; Quiles, J.L.; Ramirez-Tortosa, C.L.; Sanchez-Rovira, P.; Ramirez-Tortosa, M.C.

Hydroxytyrosol: From laboratory investigations to future clinical trials. Nutr. Rev. 2010, 68, 191�206.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

139. Carluccio, M.A.; Siculella, L.; Ancora, M.A.; Massaro, M.; Scoditti, E.; Storelli, C.; Visioli, F.;

Distante, A.; De Caterina, R. Olive oil and red wine antioxidant polyphenols inhibit endothelial activation:

Antiatherogenic properties of Mediterranean diet phytochemicals. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2003, 23,

622�629. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

140. Visioli, F.; Bernardini, E. Extra virgin olive oil�s polyphenols: Biological activities. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2011, 17,

786�804. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

141. Nabavi, S.F.; Russo, G.L.; Daglia, M.; Nabavi, S.M. Role of quercetin as an alternative for obesity treatment:

You are what you eat! Food Chem. 2015, 179, 305�310. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

142. Vinayagam, R.; Xu, B. Antidiabetic properties of dietary flavonoids: A cellular mechanism review.

Nutr. Metab. 2015, 12, 60. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

143. Shibata, T.; Nakashima, F.; Honda, K.; Lu, Y.J.; Kondo, T.; Ushida, Y.; Aizawa, K.; Suganuma, H.; Oe, S.;

Tanaka, H.; et al. Toll-like receptors as a target of food-derived anti-inflammatory compounds. J. Biol. Chem.

2014, 289, 32757�32772. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

144. Ahn, J.; Lee, H.; Kim, S.; Park, J.; Ha, T. The anti-obesity effect of quercetin is mediated by the AMPK and

MAPK signaling pathways. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 373, 545�549. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

145. Fang, X.K.; Gao, J.; Zhu, D.N. Kaempferol and quercetin isolated from Euonymus alatus improve glucose

uptake of 3T3-L1 cells without adipogenesis activity. Life Sci. 2008, 82, 615�622. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

146. Clark, J.L.; Zahradka, P.; Taylor, C.G. Efficacy of flavonoids in the management of high blood pressure.

Nutr. Rev. 2015, 73, 799�822. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

147. D�Andrea, G. Quercetin: A flavonol with multifaceted therapeutic applications? Fitoterapia 2015, 106, 256�271.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

148. Larson, A.; Witman, M.A.; Guo, Y.; Ives, S.; Richardson, R.S.; Bruno, R.S.; Jalili, T.; Symons, J.D. Acute,

quercetin-induced reductions in blood pressure in hypertensive individuals are not secondary to lower

plasma angiotensin-converting enzyme activity or endothelin-1: Nitric oxide. Nutr. Res. 2012, 32, 557�564.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

149. Tome-Carneiro, J.; Gonzalvez, M.; Larrosa, M.; Yanez-Gascon, M.J.; Garcia-Almagro, F.J.; Ruiz-Ros, J.A.;

Tomas-Barberan, F.A.; Garcia-Conesa, M.T.; Espin, J.C. Resveratrol in primary and secondary prevention of

cardiovascular disease: A dietary and clinical perspective. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2013, 1290, 37�51. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

150. Leonard, S.S.; Xia, C.; Jiang, B.H.; Stinefelt, B.; Klandorf, H.; Harris, G.K.; Shi, X. Resveratrol scavenges

reactive oxygen species and effects radical-induced cellular responses. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003,

309, 1017�1026. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

151. Ren, Z.; Wang, L.; Cui, J.; Huoc, Z.; Xue, J.; Cui, H.; Mao, Q.; Yang, R. Resveratrol inhibits NF-?B signaling

through suppression of p65 and I?B kinase activities. Die Pharm. 2013, 68, 689�694.

152. Latruffe, N.; Lancon, A.; Frazzi, R.; Aires, V.; Delmas, D.; Michaille, J.J.; Djouadi, F.; Bastin, J.;

Cherkaoui-Malki, M. Exploring new ways of regulation by resveratrol involving miRNAs, with emphasis on

inflammation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015, 1348, 97�106. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

153. Hausenblas, H.A.; Schoulda, J.A.; Smoliga, J.M. Resveratrol treatment as an adjunct to pharmacological

management in type 2 diabetes mellitus�Systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2015,

59, 147�159. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

154. Liu, K.; Zhou, R.; Wang, B.; Mi, M.T. Effect of resveratrol on glucose control and insulin sensitivity:

A meta-analysis of 11 randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 99, 1510�1519. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

155. Bitterman, J.L.; Chung, J.H. Metabolic effects of resveratrol: Addressing the controversies. Cell. Mol. Life Sci.

2015, 72, 1473�1488. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

156. Han, S.; Park, J.S.; Lee, S.; Jeong, A.L.; Oh, K.S.; Ka, H.I.; Choi, H.J.; Son, W.C.; Lee, W.Y.; Oh, S.J.; et al.

CTRP1 protects against diet-induced hyperglycemia by enhancing glycolysis and fatty acid oxidation.

J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 27, 43�52. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

157. Gambini, J.; Ingles, M.; Olaso, G.; Lopez-Grueso, R.; Bonet-Costa, V.; Gimeno-Mallench, L.; Mas-Bargues, C.;

Abdelaziz, K.M.; Gomez-Cabrera, M.C.; Vina, J.; et al. Properties of Resveratrol: In Vitro and In Vivo

Studies about Metabolism, Bioavailability, and Biological Effects in Animal Models and Humans. Oxid. Med.

Cell. Longev. 2015, 2015, 837042. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

158. Yang, C.S.; Suh, N. Cancer prevention by different forms of tocopherols. Top. Curr. Chem. 2013, 329, 21�33.

[PubMed]

159. Jiang, Q. Natural forms of vitamin E: Metabolism, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities and their

role in disease prevention and therapy. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 72, 76�90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

160. Witting, P.K.; Upston, J.M.; Stocker, R. The molecular action of alpha-tocopherol in lipoprotein lipid

peroxidation. Pro- and antioxidant activity of vitamin E in complex heterogeneous lipid emulsions.

In Fat-Soluble Vitamins; Quinn, P.J., Kagan, V.E., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA; pp. 345�390.

161. Saboori, S.; Shab-Bidar, S.; Speakman, J.R.; Yousefi Rad, E.; Djafarian, K. Effect of vitamin E supplementation

on serum C-reactive protein level: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015,

69, 867�873. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

162. Azzi, A.; Meydani, S.N.; Meydani, M.; Zingg, J.M. The rise, the fall and the renaissance of vitamin E.

Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2016, 595, 100�108. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

163. Raederstorff, D.; Wyss, A.; Calder, P.C.; Weber, P.; Eggersdorfer, M. Vitamin E function and requirements in

relation to PUFA. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 114, 1113�1122. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

164. Loffredo, L.; Perri, L.; Di Castelnuovo, A.; Iacoviello, L.; De Gaetano, G.; Violi, F. Supplementation

with vitamin E alone is associated with reduced myocardial infarction: A meta-analysis. Nutr. Metab.

Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 25, 354�363. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

165. Giampieri, F.; Tulipani, S.; Alvarez-Suarez, J.M.; Quiles, J.L.; Mezzetti, B.; Battino, M. The strawberry:

Composition, nutritional quality, and impact on human health. Nutrition 2012, 28, 9�19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

166. Amiot, M.J.; Riva, C.; Vinet, A. Effects of dietary polyphenols on metabolic syndrome features in humans:

A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2016, 17, 573�586. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

167. Smeriglio, A.; Barreca, D.; Bellocco, E.; Trombetta, D. Chemistry, Pharmacology and Health Benefits of

Anthocyanins. Phytother. Res. 2016, 30, 1265�1286. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

168. Lila, M.A. Anthocyanins and Human Health: An In Vitro Investigative Approach. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2004,

2004, 306�313. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

169. Stull, A.J.; Cash, K.C.; Johnson, W.D.; Champagne, C.M.; Cefalu, W.T. Bioactives in blueberries improve

insulin sensitivity in obese, insulin-resistant men and women. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 1764�1768. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

170. Zhu, Y.; Xia, M.; Yang, Y.; Liu, F.; Li, Z.; Hao, Y.; Mi, M.; Jin, T.; Ling, W. Purified anthocyanin supplementation

improves endothelial function via NO-cGMP activation in hypercholesterolemic individuals. Clin. Chem.

2011, 57, 1524�1533. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

171. Qin, Y.; Xia, M.; Ma, J.; Hao, Y.; Liu, J.; Mou, H.; Cao, L.; Ling, W. Anthocyanin supplementation improves

serum LDL- and HDL-cholesterol concentrations associated with the inhibition of cholesteryl ester transfer

protein in dyslipidemic subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 485�492. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

172. Zhu, Y.; Ling, W.; Guo, H.; Song, F.; Ye, Q.; Zou, T.; Li, D.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G.; Xiao, Y.; et al. Anti-inflammatory

effect of purified dietary anthocyanin in adults with hypercholesterolemia: A randomized controlled trial.

Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2013, 23, 843�849. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

173. Zhu, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Sun, R.; Xia, M. Anthocyanin supplementation

improves HDL-associated paraoxonase 1 activity and enhances cholesterol efflux capacity in subjects

with hypercholesterolemia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, 561�569. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

174. Karlsen, A.; Retterstol, L.; Laake, P.; Paur, I.; Bohn, S.K.; Sandvik, L.; Blomhoff, R. Anthocyanins inhibit

nuclear factor-kappaB activation in monocytes and reduce plasma concentrations of pro-inflammatory

mediators in healthy adults. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 1951�1954. [PubMed]

175. Keske, M.A.; Ng, H.L.; Premilovac, D.; Rattigan, S.; Kim, J.A.; Munir, K.; Yang, P.; Quon, M.J. Vascular and

metabolic actions of the green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin gallate. Curr. Med. Chem. 2015, 22, 59�69.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

176. Johnson, R.; Bryant, S.; Huntley, A.L. Green tea and green tea catechin extracts: An overview of the clinical

evidence. Maturitas 2012, 73, 280�287. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

177. Huang, J.; Wang, Y.; Xie, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wan, X. The anti-obesity effects of green tea in human

intervention and basic molecular studies. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 68, 1075�1087. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

178. Hursel, R.; Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S. Catechin- and caffeine-rich teas for control of body weight in humans.

Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 1682S�1693S. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

179. Gutierrez-Salmean, G.; Ortiz-Vilchis, P.; Vacaseydel, C.M.; Rubio-Gayosso, I.; Meaney, E.; Villarreal, F.;

Ramirez-Sanchez, I.; Ceballos, G. Acute effects of an oral supplement of (?)-epicatechin on postprandial fat

and carbohydrate metabolism in normal and overweight subjects. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 521�527. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

180. Khalesi, S.; Sun, J.; Buys, N.; Jamshidi, A.; Nikbakht-Nasrabadi, E.; Khosravi-Boroujeni, H. Green tea

catechins and blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.

Eur. J. Nutr. 2014, 53, 1299�1311. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

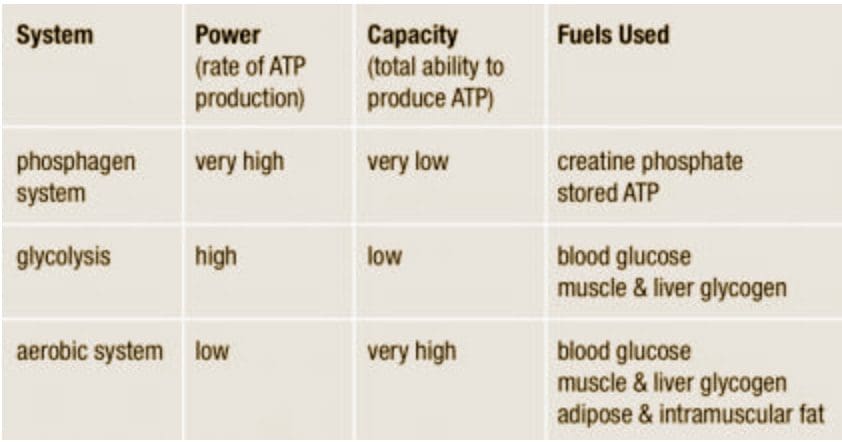

We usually talk of energy in general terms, as in �I don�t have a lot of energy today� or �You can feel the energy in the room.� But what really is energy? Where do we get the energy to move? How do we use it? How do we get more of it? Ultimately, what controls our movements? The three metabolic energy pathways are the�phosphagen system, glycolysis�and the�aerobic system.�How do they work, and what is their effect?

We usually talk of energy in general terms, as in �I don�t have a lot of energy today� or �You can feel the energy in the room.� But what really is energy? Where do we get the energy to move? How do we use it? How do we get more of it? Ultimately, what controls our movements? The three metabolic energy pathways are the�phosphagen system, glycolysis�and the�aerobic system.�How do they work, and what is their effect? The energy for all physical activity comes from the conversion of high-energy phosphates (adenosine�triphosphate�ATP) to lower-energy phosphates (adenosine�diphosphate�ADP; adenosine�monophosphate�AMP; and inorganic phosphate, Pi). During this breakdown (hydrolysis) of ATP, which is a water-requiring process, a proton, energy and heat are produced: ATP + H2O ���ADP + Pi�+ H+�+ energy + heat. Since our muscles don�t store much ATP, we must constantly resynthesize it. The hydrolysis and resynthesis of ATP is thus a circular process�ATP is hydrolyzed into ADP and Pi, and then ADP and Pi�combine to resynthesize ATP. Alternatively, two ADP molecules can combine to produce ATP and AMP: ADP + ADP ���ATP + AMP.

The energy for all physical activity comes from the conversion of high-energy phosphates (adenosine�triphosphate�ATP) to lower-energy phosphates (adenosine�diphosphate�ADP; adenosine�monophosphate�AMP; and inorganic phosphate, Pi). During this breakdown (hydrolysis) of ATP, which is a water-requiring process, a proton, energy and heat are produced: ATP + H2O ���ADP + Pi�+ H+�+ energy + heat. Since our muscles don�t store much ATP, we must constantly resynthesize it. The hydrolysis and resynthesis of ATP is thus a circular process�ATP is hydrolyzed into ADP and Pi, and then ADP and Pi�combine to resynthesize ATP. Alternatively, two ADP molecules can combine to produce ATP and AMP: ADP + ADP ���ATP + AMP. During short-term, intense activities, a large amount of power needs to be produced by the muscles, creating a high demand for ATP. The phosphagen system (also called the ATP-CP system) is the quickest way to resynthesize ATP (Robergs & Roberts 1997). Creatine phosphate (CP), which is stored in skeletal muscles, donates a phosphate to ADP to produce ATP: ADP + CP ���ATP + C. No carbohydrate or fat is used in this process; the regeneration of ATP comes solely from stored CP. Since this process does not need oxygen to resynthesize ATP, it is anaerobic, or oxygen-independent. As the fastest way to resynthesize ATP, the phosphagen system is the predominant energy system used for all-out exercise lasting up to about 10 seconds. However, since there is a limited amount of stored CP and ATP in skeletal muscles, fatigue occurs rapidly.

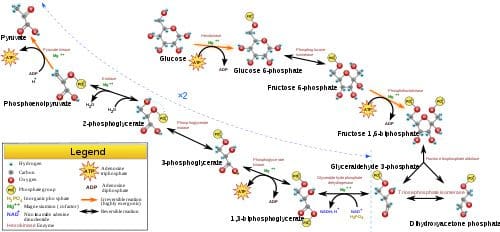

During short-term, intense activities, a large amount of power needs to be produced by the muscles, creating a high demand for ATP. The phosphagen system (also called the ATP-CP system) is the quickest way to resynthesize ATP (Robergs & Roberts 1997). Creatine phosphate (CP), which is stored in skeletal muscles, donates a phosphate to ADP to produce ATP: ADP + CP ���ATP + C. No carbohydrate or fat is used in this process; the regeneration of ATP comes solely from stored CP. Since this process does not need oxygen to resynthesize ATP, it is anaerobic, or oxygen-independent. As the fastest way to resynthesize ATP, the phosphagen system is the predominant energy system used for all-out exercise lasting up to about 10 seconds. However, since there is a limited amount of stored CP and ATP in skeletal muscles, fatigue occurs rapidly. Glycolysis is the predominant energy system used for all-out

Glycolysis is the predominant energy system used for all-out  Since humans evolved for aerobic activities (Hochachka, Gunga & Kirsch 1998; Hochachka & Monge 2000), it�s not surprising that the aerobic system, which is dependent on oxygen, is the most complex of the three energy systems. The metabolic reactions that take place in the presence of oxygen are responsible for most of the cellular energy produced by the body. However, aerobic metabolism is the slowest way to resynthesize ATP. Oxygen, as the patriarch of metabolism, knows that it is worth the wait, as it controls the fate of endurance and is the sustenance of life. �I�m oxygen,� it says to the muscle, with more than a hint of superiority. �I can give you a lot of ATP, but you will have to wait for it.�

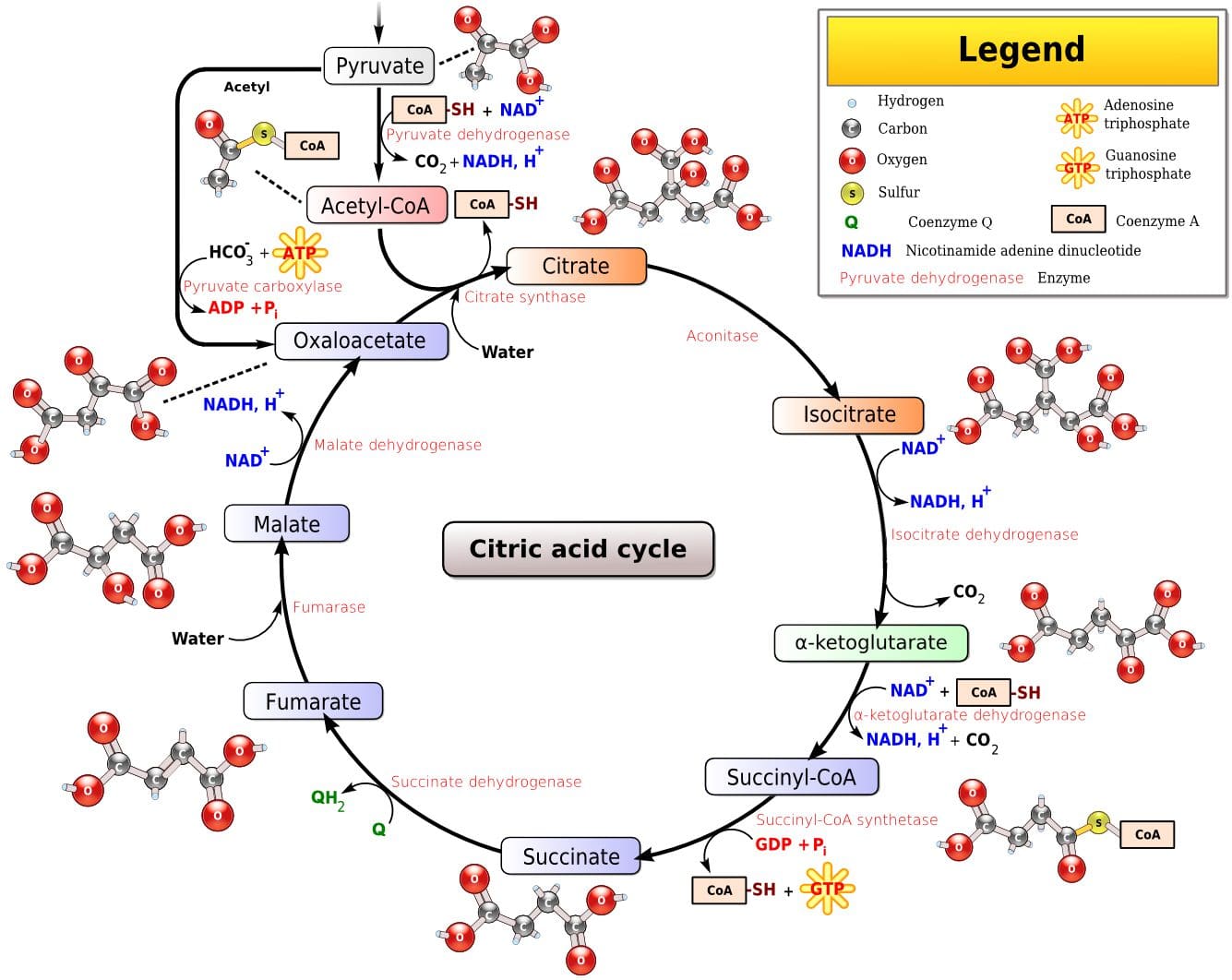

Since humans evolved for aerobic activities (Hochachka, Gunga & Kirsch 1998; Hochachka & Monge 2000), it�s not surprising that the aerobic system, which is dependent on oxygen, is the most complex of the three energy systems. The metabolic reactions that take place in the presence of oxygen are responsible for most of the cellular energy produced by the body. However, aerobic metabolism is the slowest way to resynthesize ATP. Oxygen, as the patriarch of metabolism, knows that it is worth the wait, as it controls the fate of endurance and is the sustenance of life. �I�m oxygen,� it says to the muscle, with more than a hint of superiority. �I can give you a lot of ATP, but you will have to wait for it.� Fat, which is stored as triglyceride in adipose tissue underneath the skin and within skeletal muscles (called�intramuscular triglyceride), is the other major fuel for the aerobic system, and is the largest store of energy in the body. When using fat, triglycerides are first broken down into free fatty acids and glycerol (a process called�lipolysis). The free fatty acids, which are composed of a long chain of carbon atoms, are transported to the muscle mitochondria, where the carbon atoms are used to produce acetyl-CoA (a process called�beta-oxidation).

Fat, which is stored as triglyceride in adipose tissue underneath the skin and within skeletal muscles (called�intramuscular triglyceride), is the other major fuel for the aerobic system, and is the largest store of energy in the body. When using fat, triglycerides are first broken down into free fatty acids and glycerol (a process called�lipolysis). The free fatty acids, which are composed of a long chain of carbon atoms, are transported to the muscle mitochondria, where the carbon atoms are used to produce acetyl-CoA (a process called�beta-oxidation).

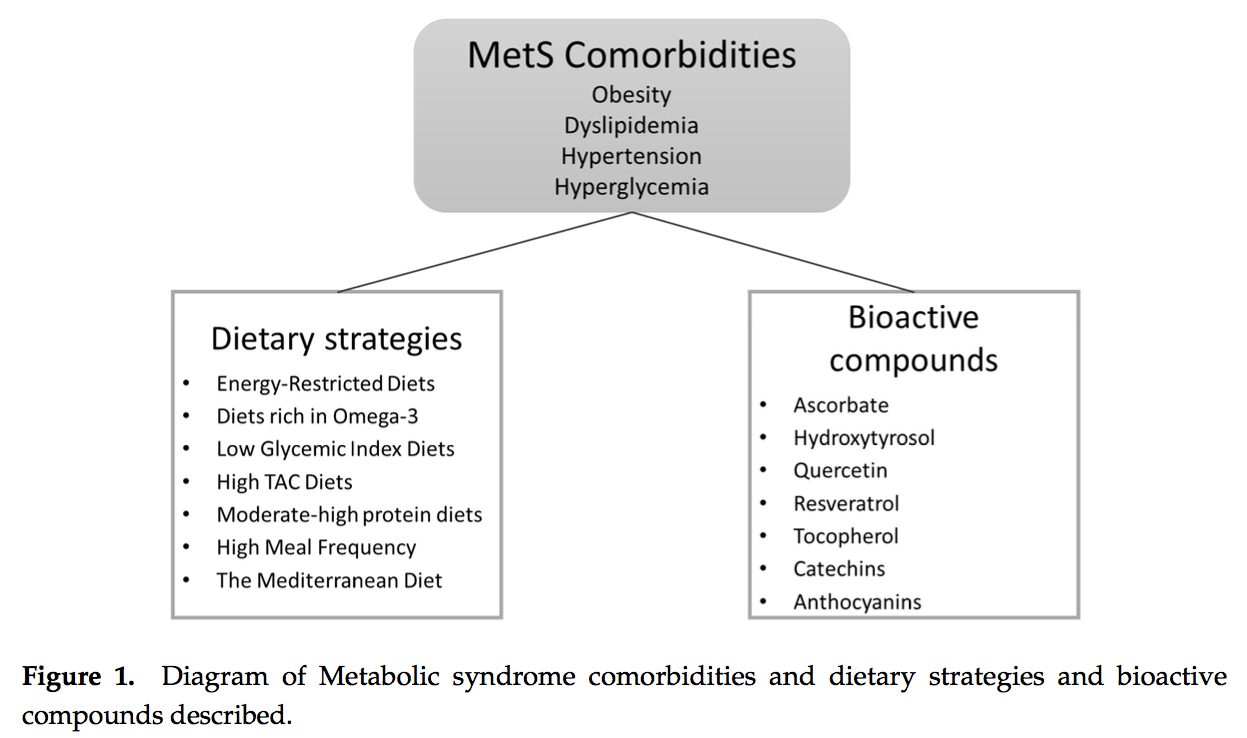

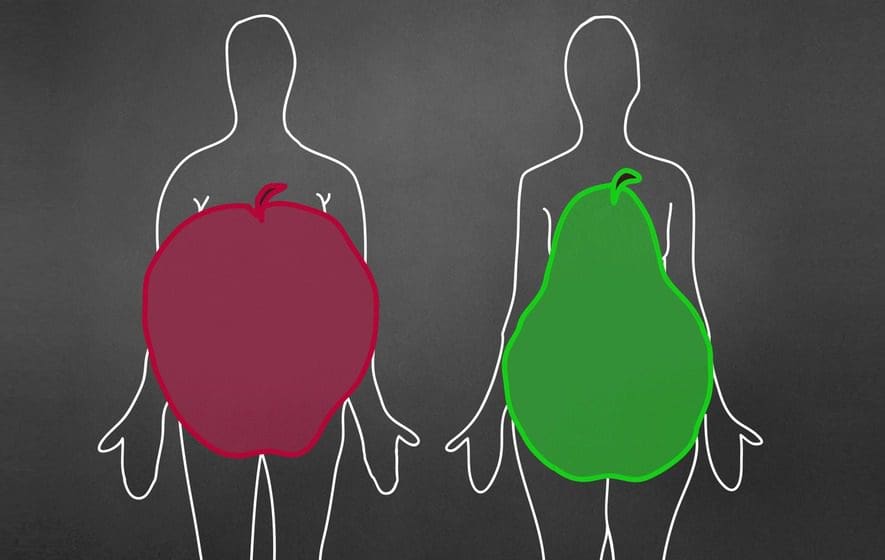

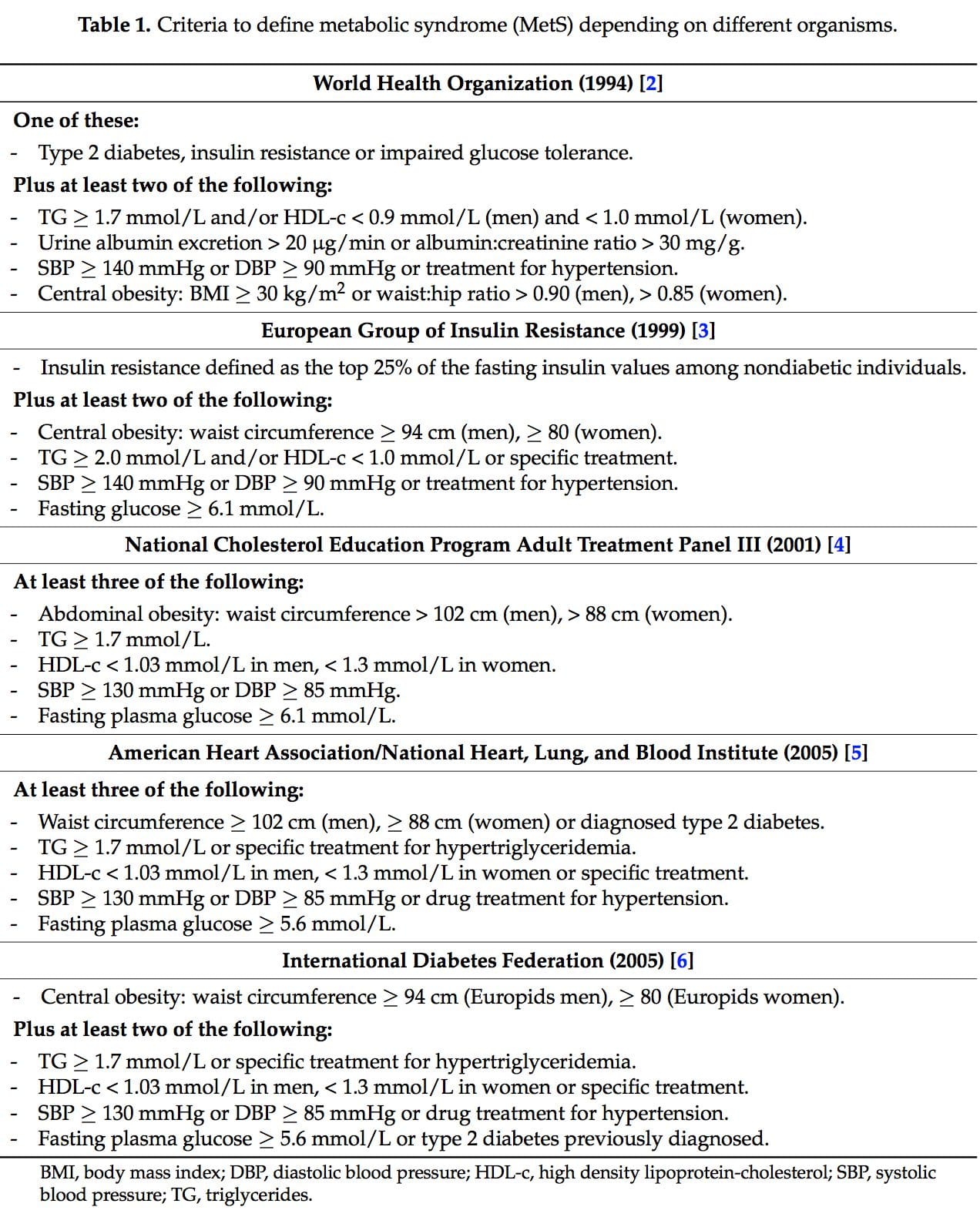

It was during the period between 1910 and 1920 when it was suggested for the first time that a cluster of associated metabolic disturbances tended to coexist together [1]. Since then, different health organisms have suggested diverse definitions for metabolic syndrome (MetS) but there has not yet been a well-established consensus. The most common definitions are summarized in Table 1. What is clear for all of these is that the MetS is a clinical entity of substantial heterogeneity, commonly represented by the combination of obesity (especially abdominal obesity), hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia and/or hypertension [2�6].

It was during the period between 1910 and 1920 when it was suggested for the first time that a cluster of associated metabolic disturbances tended to coexist together [1]. Since then, different health organisms have suggested diverse definitions for metabolic syndrome (MetS) but there has not yet been a well-established consensus. The most common definitions are summarized in Table 1. What is clear for all of these is that the MetS is a clinical entity of substantial heterogeneity, commonly represented by the combination of obesity (especially abdominal obesity), hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia and/or hypertension [2�6].

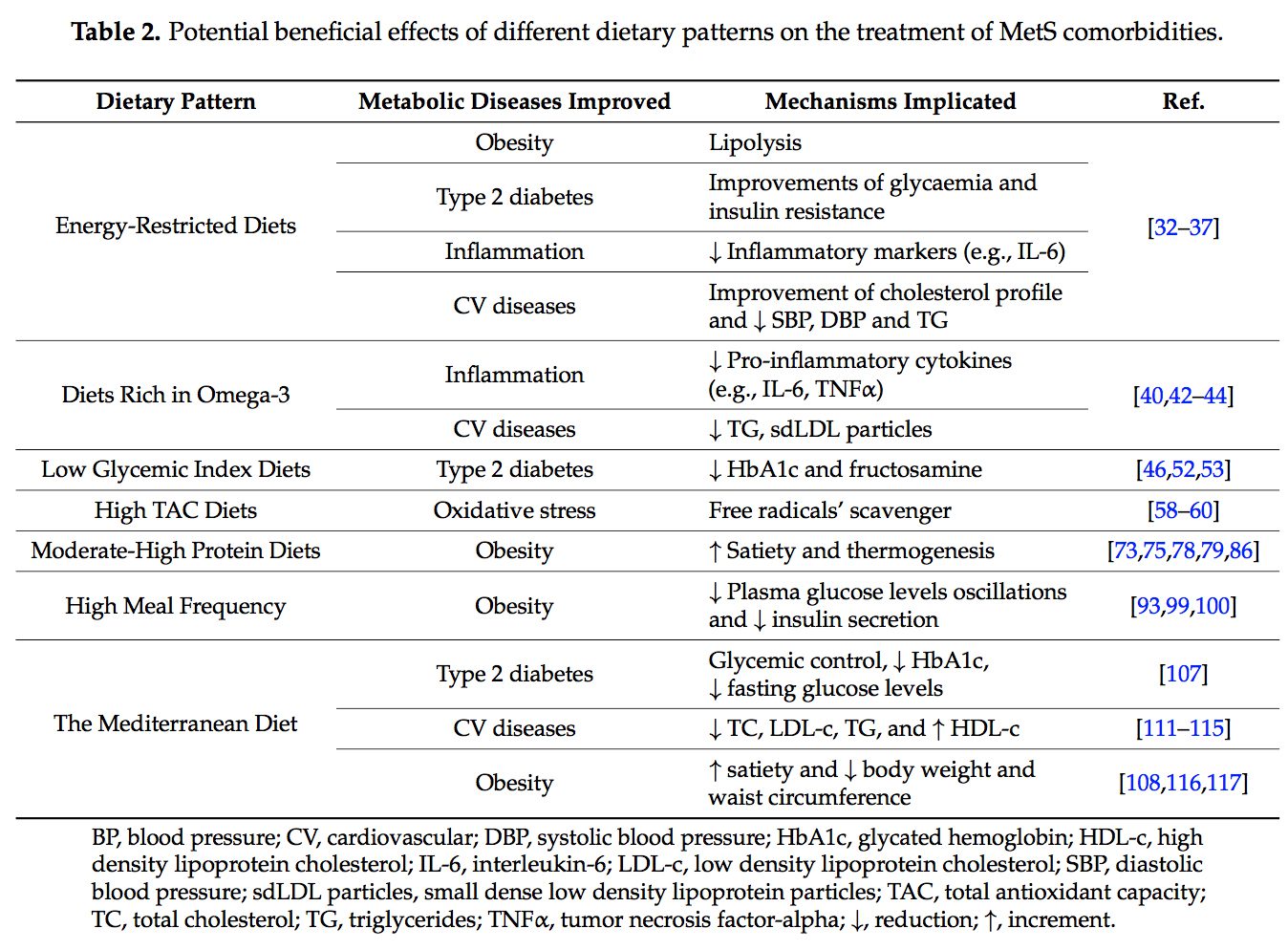

Several dietary strategies and their potential positive effects on the prevention and treatment of the different metabolic complications associated to the MetS, are described below and summarized in Table 2.

Several dietary strategies and their potential positive effects on the prevention and treatment of the different metabolic complications associated to the MetS, are described below and summarized in Table 2. 2.1. Energy-Restricted Diet Strategies

2.1. Energy-Restricted Diet Strategies

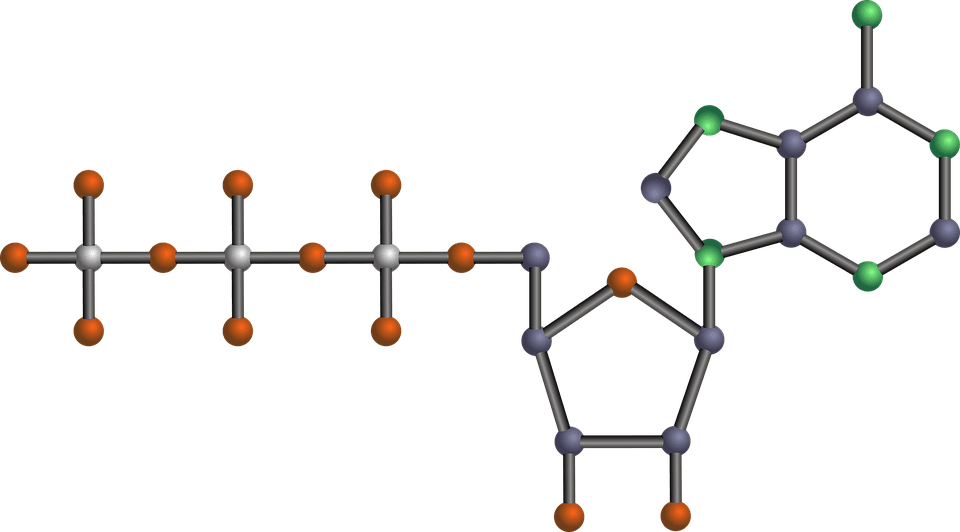

The very long-chain eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) are essential omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFAs) for human physiology. Their main dietary sources are fish and algal oils and fatty fish, but they can also be synthesized by humans from ?-linolenic acid [40].

The very long-chain eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) are essential omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFAs) for human physiology. Their main dietary sources are fish and algal oils and fatty fish, but they can also be synthesized by humans from ?-linolenic acid [40]. Over the last ten years, the concern about the quality of the carbohydrates (CHO) consumed has risen [46]. In this context, the glycemic index (GI) is used as a CHO quality measure. It consists in a ranking on a scale from 0 to 100 that classifies carbohydrate-containing foods according to the postprandial glucose response [47]. The higher the index, the more promptly the postprandial serum glucose rises and the more rapid the insulin response. A quick insulin response leads to rapid hypoglycemia, which is suggested to be associated with an increment of the feeling of hunger and to a subsequent higher caloric intake [47]. The glycemic load (GL) is equal to the GI multiplied by the number of grams of CHO in a serving [48].

Over the last ten years, the concern about the quality of the carbohydrates (CHO) consumed has risen [46]. In this context, the glycemic index (GI) is used as a CHO quality measure. It consists in a ranking on a scale from 0 to 100 that classifies carbohydrate-containing foods according to the postprandial glucose response [47]. The higher the index, the more promptly the postprandial serum glucose rises and the more rapid the insulin response. A quick insulin response leads to rapid hypoglycemia, which is suggested to be associated with an increment of the feeling of hunger and to a subsequent higher caloric intake [47]. The glycemic load (GL) is equal to the GI multiplied by the number of grams of CHO in a serving [48]. Dietary total antioxidant capacity (TAC) is an indicator of diet quality defined as the sum of antioxidant activities of the pool of antioxidants present in a food [55]. These antioxidants have the capacity to act as scavengers of free radicals and other reactive species produced in the organisms [56]. Taking into account that oxidative stress is one of the remarkable unfortunate physiological states of MetS, dietary antioxidants are of main interest in the prevention and treatment of this multifactorial disorder [57]. Accordingly, it is well-accepted that diets with a high content of spices, herbs, fruits, vegetables, nuts and chocolate, are associated with a decreased risk of oxidative stress-related diseases development [58�60]. Moreover, several studies have analyzed the effects of dietary TAC in individuals suffering from MetS or related diseases [61,62]. In the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study it was demonstrated that a high TAC has beneficial effects on metabolic disorders and especially prevents weight and abdominal fat gain [61]. In the same line, research conducted in our institutions also evidenced that beneficial effects on body weight, oxidative stress biomarkers and other MetS features were positively related with higher TAC consumption in patients suffering from MetS [63�65].

Dietary total antioxidant capacity (TAC) is an indicator of diet quality defined as the sum of antioxidant activities of the pool of antioxidants present in a food [55]. These antioxidants have the capacity to act as scavengers of free radicals and other reactive species produced in the organisms [56]. Taking into account that oxidative stress is one of the remarkable unfortunate physiological states of MetS, dietary antioxidants are of main interest in the prevention and treatment of this multifactorial disorder [57]. Accordingly, it is well-accepted that diets with a high content of spices, herbs, fruits, vegetables, nuts and chocolate, are associated with a decreased risk of oxidative stress-related diseases development [58�60]. Moreover, several studies have analyzed the effects of dietary TAC in individuals suffering from MetS or related diseases [61,62]. In the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study it was demonstrated that a high TAC has beneficial effects on metabolic disorders and especially prevents weight and abdominal fat gain [61]. In the same line, research conducted in our institutions also evidenced that beneficial effects on body weight, oxidative stress biomarkers and other MetS features were positively related with higher TAC consumption in patients suffering from MetS [63�65]. The macronutrient distribution set in a weight loss dietary plan has commonly been 50%�55% total caloric value from CHO, 15% from proteins and 30% from lipids [57,68]. However, as most people have difficulty in maintaining weight loss achievements over time [69,70], research on increment of protein intake (>20%) at the expense of CHO was carried out [71�77].

The macronutrient distribution set in a weight loss dietary plan has commonly been 50%�55% total caloric value from CHO, 15% from proteins and 30% from lipids [57,68]. However, as most people have difficulty in maintaining weight loss achievements over time [69,70], research on increment of protein intake (>20%) at the expense of CHO was carried out [71�77].

The concept of the

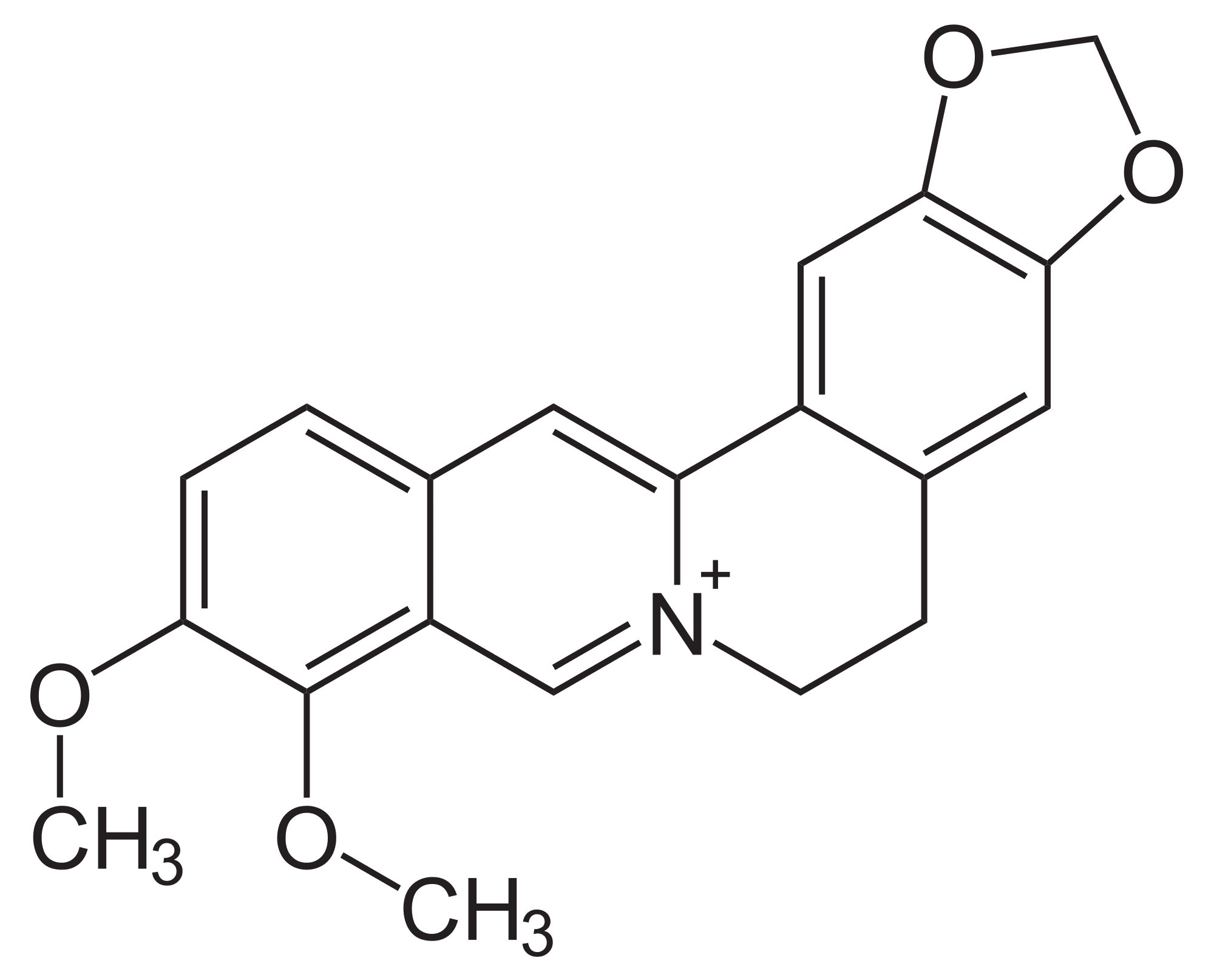

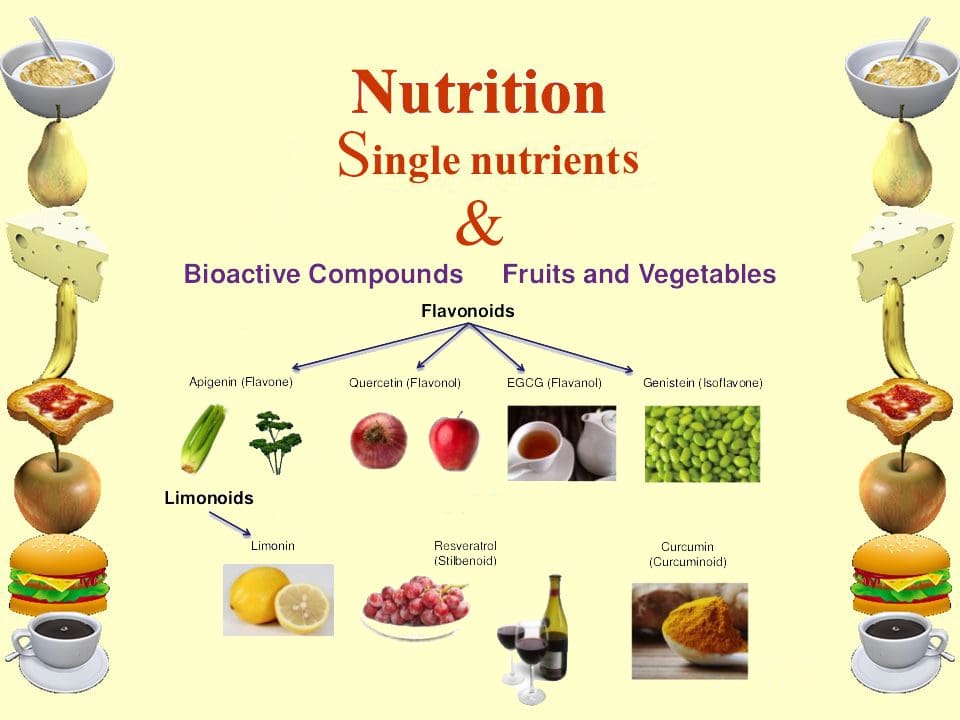

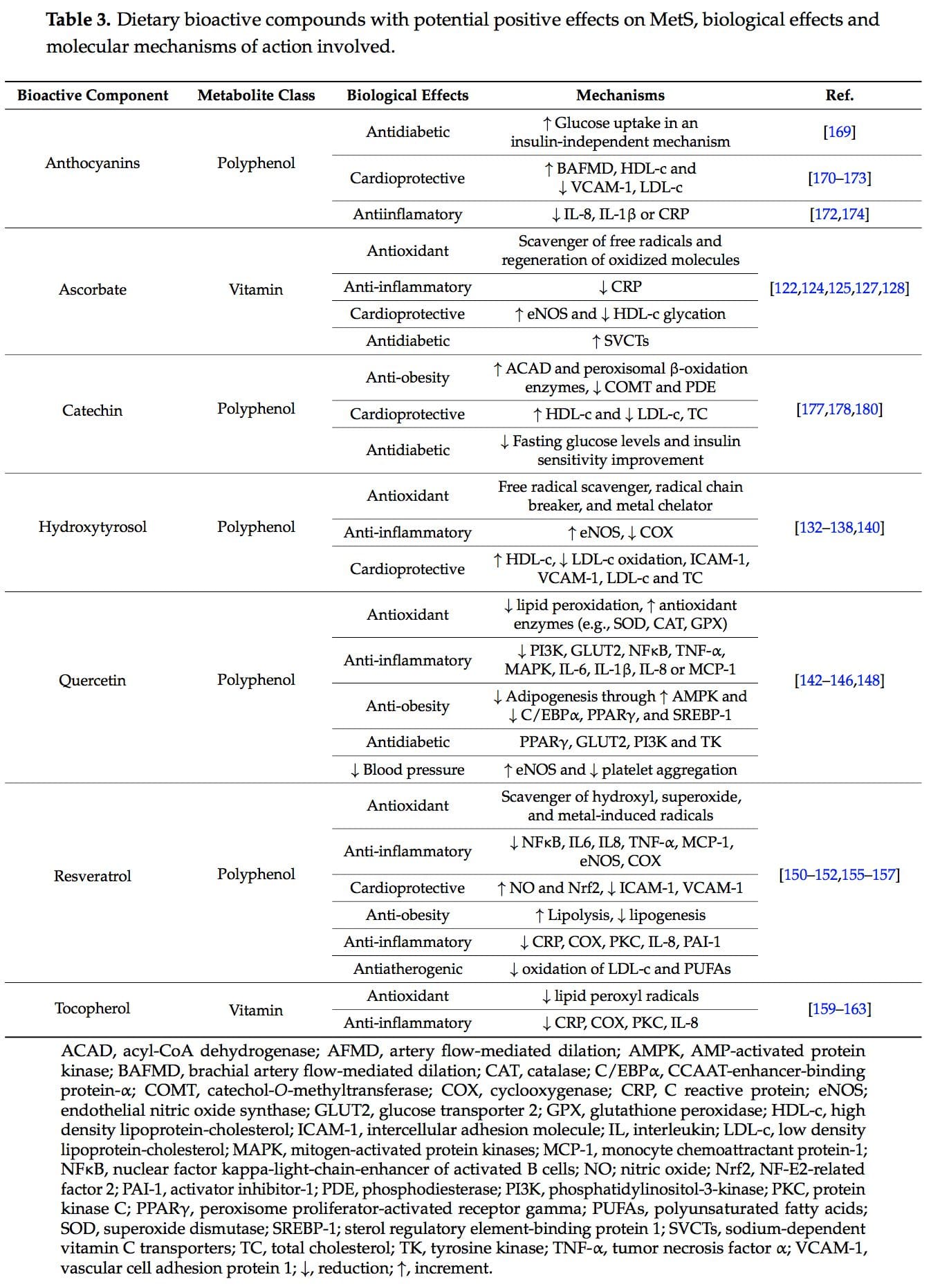

The concept of the  New studies focused on the molecular action of nutritional bioactive compounds with positive effects on MetS are currently an objective of scientific research worldwide with the aim of designing more personalized strategies in the framework of molecular nutrition. Among them, flavonoids and antioxidant vitamins are some of the most studied compounds with different potential benefits such as antioxidant, vasodilatory, anti-atherogenic, antithrombotic, and anti-inflammatory effects [119]. Table 3 summarizes different nutritional bioactive compounds with potential positive effects on MetS, including the possible molecular mechanism of action involved.

New studies focused on the molecular action of nutritional bioactive compounds with positive effects on MetS are currently an objective of scientific research worldwide with the aim of designing more personalized strategies in the framework of molecular nutrition. Among them, flavonoids and antioxidant vitamins are some of the most studied compounds with different potential benefits such as antioxidant, vasodilatory, anti-atherogenic, antithrombotic, and anti-inflammatory effects [119]. Table 3 summarizes different nutritional bioactive compounds with potential positive effects on MetS, including the possible molecular mechanism of action involved.

Vitamin C, ascorbic acid or ascorbate is an essential nutrient as human beings cannot synthesize it. It is a water-soluble antioxidant mainly found in fruits, especially citrus (lemon, orange), and vegetables (pepper, kale) [120]. Several beneficial effects have been associated to this vitamin such as antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties and prevention or treatment of CVD and type 2 diabetes [121�123].

Vitamin C, ascorbic acid or ascorbate is an essential nutrient as human beings cannot synthesize it. It is a water-soluble antioxidant mainly found in fruits, especially citrus (lemon, orange), and vegetables (pepper, kale) [120]. Several beneficial effects have been associated to this vitamin such as antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties and prevention or treatment of CVD and type 2 diabetes [121�123]. Hydroxytyrosol (3,4-dihydroxyphenylethanol) is a phenolic compound mainly found in olives [132].

Hydroxytyrosol (3,4-dihydroxyphenylethanol) is a phenolic compound mainly found in olives [132]. Quercetin is a predominant flavanol naturally present in vegetables, fruits, green tea or red wine. It is commonly found as glycoside forms, where rutin is the most common and important structure found in nature [141].

Quercetin is a predominant flavanol naturally present in vegetables, fruits, green tea or red wine. It is commonly found as glycoside forms, where rutin is the most common and important structure found in nature [141].

Tocopherols, also known as vitamin E, are a family of eight fat-soluble phenolic compounds whose main dietary sources are vegetable oils, nuts and seeds [130,158].

Tocopherols, also known as vitamin E, are a family of eight fat-soluble phenolic compounds whose main dietary sources are vegetable oils, nuts and seeds [130,158].

Catechins are polyphenols that can be found in a variety of foods including fruits, vegetables, chocolate, wine, and tea [175]. The epigallocatechin 3-gallate present in tea leaves is the catechin class most studied [176].

Catechins are polyphenols that can be found in a variety of foods including fruits, vegetables, chocolate, wine, and tea [175]. The epigallocatechin 3-gallate present in tea leaves is the catechin class most studied [176].