Podcast: BIA and Basal Metabolic Rate Explained

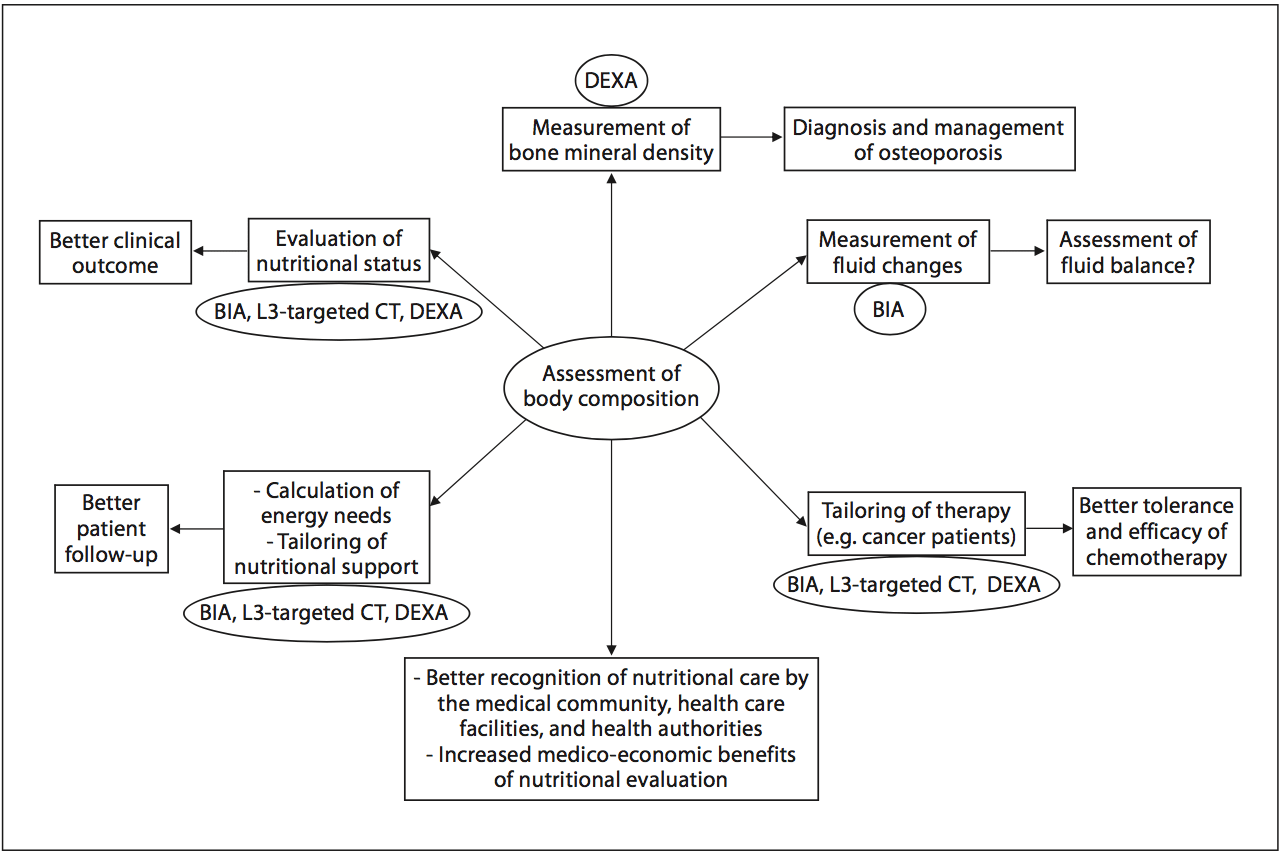

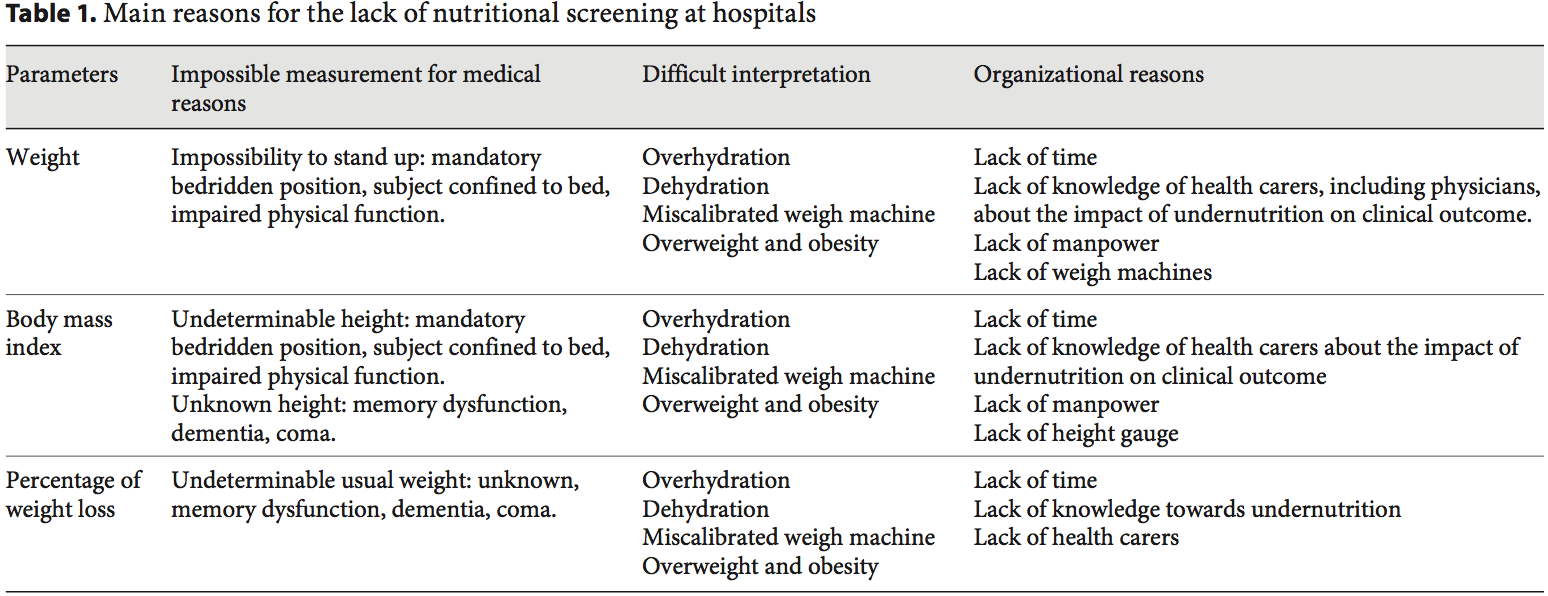

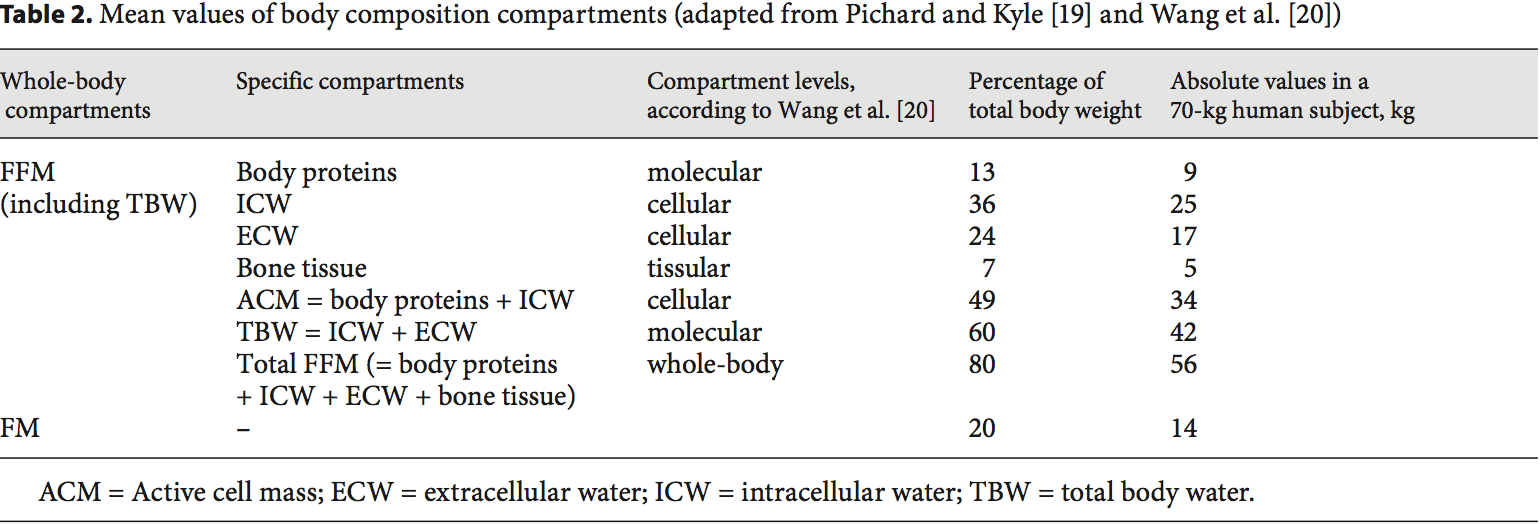

Dr. Alex Jimenez and Dr. Mario Ruja discuss basal metabolic rate, BMI, and BIA. Body mass and body fat can be measured in a variety of ways, however, several measurement tools may ultimately be inaccurate for many athletes. According to Dr. Alex Jimenez and Dr. Mario Ruja, calculating an individual’s body mass and body fat utilizing various tools is essential to determine overall health and wellness. BMI uses a person’s height divided by twice their weight. The results may be inaccurate for athletes because their body mass and body fat is different, in terms of weight, compared to the average person. Dr. Alex Jimenez and Dr. Mario Ruja demonstrate that BIA, or bioelectrical impedance analysis, and various other tools, such as the DEXA test, the Tanita scale, and the InBody, among others, can help more accurately determine an athlete’s body mass and body fat. Basal metabolic rate, BMI, and BIA is essential for parents that have young athletes as well as for the general population. Healthcare professionals that have these tools available can ultimately help provide individuals with the results they may need to maintain overall health and wellness.

Podcast Insight

[00:00:08] All right. It’s Mario and Alex time. The two favorite chiropractors from El Paso, TX. Ok. We’re going to be… Functional medicine, Alex. That’s what we’re gonna do. It’s about functional medicine in 2020, baby.

[00:00:21] This 2020, we’re gonna be focusing on BMI and we’re gonna be focusing on everything. Mario, my awesome co-host here we’re tearing it up. We’re gonna give some points of view. We’re gonna be discussing certain things. Today our focus is going to be on anthropometric measurements and measuring the body composition rationale and its interpretation.

[00:00:46] Now I’m afraid of that. All right.

[00:00:49] I’m afraid of measurements, Alex, I’m telling you right now, I don’t want measurements around my body.

[00:00:55] Okay. Thank you. All right Mario. Yeah.

[00:01:00] Mario, we’ve got to get a little bit of knowledge here. Okay. Well, what we’re not going to do is we’re not going to try to make this boring. No. If you really want to see boring. I think we have plenty of examples of what boring looks like. Yeah. Have you seen those boring guys, Mario? You know, it’s like the measurement of what’s going on. Yeah. Here you go.

[00:01:20] Video plays in the background.

[00:01:31] You know what? I can go to sleep with that one, Alex. Now, that’s what I’m talking about Mario. I can go to sleep and just shut it off.

[00:01:40] But, you know, learning has to be fun. It has to be interactive and it has to be functional.

[00:01:47] So that’s what we’re… Absolutely I totally agree. So what we’re gonna do is we’re gonna try to bring the facts as it can be and we’re gonna try to bring it with a little bit of slapstick fun.

[00:01:56] So it’s gonna be fun. Mario, tell me a little bit about your interpretation of BMI as how people understand basal metabolic rate.

[00:02:05] Well, this is what I understand and what I hear about basal metabolic rate.

[00:02:13] Bottom line is, can you put your belt around your pants and can you tuck your shirt in? How about that?

[00:02:25] You know, that’s pretty scientific. Right. That is scientific. Yes, that is scientific. Yes. We could talk pear, we could talk apple, sizes, apple-shaped bodies types.

[00:02:33] But we’re going to get specific here because people want to know, Ok, what’s going on. Let’s start. One of the things that we can do is we can start discussing calculating energy requirements, because one of the things that we want to see, as you can see, I put up here a little bit of facts so that it can help us out a little bit in terms of figuring out what’s the best approach in terms of what we do. Now, you can tell here that sedentary, no exercise, what we want to do is talk about basal metabolic rate. Ok. So this is a measurement that has occurred by height as well as weight index. So it comes out to that number and we can start looking at calorie, caloric intake burn. But when we do a BMR and we calculate this number, we typically want to get about a 1.2. And that’s what would be normal in most situations if you’re sedentary, light activity, we start noticing that there’s an increased activity expenditure and BMR should be one point 1.375. If you are moderately active, you should start doing that. So in its interpretation…

[00:03:33] Mario, when you see these kind of things and these kind of figures, what does it bring to mind for you in terms of these numbers? As we keep on going back to this, we’ll be able to see exactly what’s going on. What’s your incentive sense of the rates and the metabolic processes?

[00:03:52] Well, again, very simple, when you look at it as the more active you are, the higher your metabolic rate is. That’s it. So at the end of the day, we want to put it in very simplistic terms to the public. We want to be more active about that. So science is supporting that, you know, park the car as far away as possible from the Wal-Mart entrance and your work. So by doing that every day, you are creating a higher function. Ok, metabolic, that’s the burn. That’s your whole system burning fuel within yourself. So it’s simple. And the studies are showing that the more active you are, the higher your metabolic rate is. It can go up to a 1.9 from a 1.2. Correct.

[00:04:50] Exactly. So what we’re looking at here is that the requirements are going to be pretty high. If you are one of those people that are very active. So ultimately, our goal is to get you as active or what you’re your lifestyle could require. So, you know, if you’re a mechanic, you say moderately active. If you’re someone who works in, let’s say, an office, your BMR is going to be calculable. Using these numbers for the body mass index, the whole idea is to try to figure out the body mass index using the BMR. So the BMR allows us to kind of give an estimate, the best estimate as to where you’re BMR should be at and then we can use the same number, this BMR to assess your body mass index. So our goal is to continue with kind of learning about this thing. And as we kind of go through that, we look at body measurement types. Now, in the past, what we’ve looked at in terms of this, we assess the body in a bunch of different ways. Historically, we’ve been able to do a weight, underwater weight assessment. Remember, Mario, we used to have like a tank and put someone in water, have them float, actually measure the oxygen consumption. Those were the old methods, the true standard way of doing our fat analysis.

[00:05:57] Pretty expensive. Sometimes, though, we use the DEXA test. The DEXA test is a similar test that is used for bone density. We can actually do that. We also have, historically the body pod test. Now, I know that you have noticed different types of tests and we’re going to put up here.

[00:06:13] What are the other tests that you’ve seen? Alex, on that one. When you’re talking about the underwater weighing and DEXA and even the body pod, those are again, more research-based, more scientific.

[00:06:30] Exactly. In that. So when you’re looking at that, I look at it from my perspective.

[00:06:38] You know what’s functional? What’s can everyone do? Exactly. Skinfold is easy. Yeah. You know, skinfold and the BIA and the Tanita scale. Yeah. I mean that one, electrical impulses going through and you’re looking at resistance and impedance. Those are simple. You can’t just buy them from Wal-Mart or anywhere and step on it. Make sure you don’t eat and make sure you don’t drink before you do your test. So do it early morning. Let’s say six, seven o’clock. Right. On an empty stomach so you can get some good readings with the scan. And also, you know, skin fold is easy.

[00:07:21] And again, with the BMI, you’re looking at weight divided by twice your height, your height squared. Exactly.

[00:07:31] So that’s kind of like a simplistic view in terms of BMI. Anyone can do this. Yes. So those are right now. Those are the standards. Those are things, most of the time, when you go to your trainer. Most of the time when you go workout in your CrossFit gym or your, you know, what I call functional gym. Now people are going into more a functional aspect of fitness.

[00:07:55] So they incorporate less wear-and-tear and trauma. Now they’re looking at skin fold and InBody. They even have the new InBody systems that are very popular that give you a nice ratio even of your hydration, which is really nice.

[00:08:13] You know, when you actually say that, when we look at this thing like the Tanita, these scales, like you said, that you can get them at home. The BIA is where it’s at. What we’re finding is that a lot of the studies are reflecting that the BIA actually shows quite a correlation with accuracy with these more complex underwater weighing as well as the DEXA test. So these standards research-based, you’d always want to maintain some sort of research-based, at least collaborative information that makes sense. Right. So now the BIA assessment machines, they can actually determine through OHMS, through impedance to fat analysis to actually measuring the electrical current of the body, a very accurate approach to weight assessment. And by, you know, basal metabolic rates. So now the studies are actually better and they’re easier for people to do. And we don’t have to do some real complex things.

[00:09:09] Yeah. And, you know, if you can show everyone the body part, I think that’s really cool. That’s like a cool thing. You know, I mean, look at that. Can you. Yeah.

[00:09:21] Yeah. That’s really cool. So when you look at a body pod. Right.

[00:09:24] This is an incredible thing. But this is not something you would want to have in your office. Right? Thirty, Forty-thousand dollars. Right. Jesus, man.

[00:09:31] Yeah, you know, it’s crazy, I mean, they’re probably looking at you like they should have you on an alien channel or something. But the simple one, if you can scroll up on the BIA, it’s a simple machine and the readings are awesome. You know, the readings are very good. They’re portable. And you can see the resistance level and you can see the phase angle, which is really nice because then you’re looking at very specific patterns and turns your metabolism.

[00:10:06] Absolutely. These tests now are available in most clinics, or at least the clinics that focus on functional fitness. We have them at the fitness centers and many fitness centers have them. And you and I are used to using these things in our offices. So as we do these things, as we assess these things, we really can give kind of the patients a quantitative point of view that really helps them figure out exactly how everything is.

[00:10:38] You’re exactly right, Alex. You know, in my work, you know, working with athletes and also what I call performance professions, where we’re talking about military S.F., Special Forces, Rangers, things like that. It’s all about performance. So in that, we use calipers. You know, those are very, very useful, easy to use. And the one that I particularly like, which.

[00:11:08] Again, with BMI, there are a lot of discrepancies, Alex, and you know, this being, you know, in the world of bodybuilding and athletics and all of our kids are athletes. I mean, they’re, that’s just part of the family structure. That’s who we are. So now you got to run, jump, catch a ball or kick a ball or do something. Right. So the point is in that what I have found out is that the BMI is not very accurate. Not very accurate at all Alex, when it comes down to athletes. Right. So this is where the discrepancy comes in, where it gets crazy because now you go to a regular assessment, a regular assessment or a regular, I don’t want to say regular doctor, but, you know, your doctor and then he’ll test your BMI and you’re gonna be off, you’re going to be high and you’re going to say, you know, you need to get your BMI lower. Yeah, the point is that the BMI is the mass, right? So again, muscle is heavier than fat. So in your environment of bodybuilding, what do you think about that?

[00:12:22] I mean because I’m sure it was crazy. Well, one of the things that I’ve been able to see over the years is that when you have someone, as we understand this, that the BMR is obviously the thing that we’re using to assess height and weight. But those numbers get skewed when you have an athlete and they don’t work well for the muscular individual, someone that’s I mean, my son, for example, he was 195 pounds, 5′ 8″. In all reality, he’s clinically obese. Right. Yet he’s shredded and ripped. And he was a national champion in wrestling. Literally had no body fat. So the caliper method, the BMR, the BMI based on height and weight has deficiencies. And that’s where the BIA came in and the body impedance assessment. That’s where the studies became very popular. And as what we see, Mario is that in essence, when we look at these situations, we find out that there are great assessment tools out there. These tools are the ones that are actually going to give us the ability to kind of come up with an accurate for a large range of individuals, whether they’re bodybuilders, whether they’re women. There’s a standard between, you know, a good 13 percent body fat and 29 percent body fat for females. Women typically have a larger number of between 18 and 29 percent body fat. At times, that’s a range that is kind of in there. Hopefully, they can stick around 22 to 24, boys in the 13 range just because the body density is different in a female. Right. So what we look at is what’s the norm? One of the things that we can do is try to calibrate people for their numbers so that they make sense for that individual and be able to work them towards it because a true athlete will be able to almost blow the BMR, BMI into the wrong number skew. And if we can get it to a nice number, we’re gonna have to use a lot of different tools. Now, what we’re going to present today are our ideas and fundamental philosophies and knowledge points that we use to determine actual true health. Right. So we’re going to be discussing those particular issues and we’re going to go over those particular areas here. Now, the BIA is the body impedance. Okay. So when we look at the bioimpedance areas, we can see that these kinds of tests are not only just affordable, but they actually determine the electrical current. And because of the body amount of muscle fat and the fat that occurs, we are using the fat as kind of like the thing that allows us to assess body dynamics as well as body density. Right. So as the more, there’s more impedance or more ohms or more resistance in the body, the greater the body fat. So it’s very important that these tests be done properly. Many of the times before you do a BIA, you’ve got to kind of, you know, you’ve got to not take, first of all, you’ve got to be dry. Ok. Because if you’re sweaty, it throws it off. Right. If you eat too much or too many fluids. So typically you try to keep away from foods, eating food prior to this and you try to get this thing to work. So resistance, as we look at it, are the things that we’re trying to measure. So one of the things that, when you look at these particular graphs, you see low resistance associated with large amounts of body fat mass, which is where the body is stored. Right. So when we look at this, this is one of the areas we can kind of put together when we look at the resistance numbers. Now, as we look at different angles, let’s say we got the phase angles. We also look at the ability. This is the new number that is assessing actually the intracellular and extracellular activity as well as the permeability of the cells. Ok. Now, as we range this. They’re looking at ranges between 0 and 20 percent. But the higher the phase angle, Ok, the higher the number where it pops, the better it is for the individual, the lower it is. It’s not as good. So what we want to do is we want to see where your phase angle is and we want to be able to assess it as it gets calculated. So one of the things that we look at, we assess this and our tools that we use, such as the BIA assessments, such as the InBody testing systems, we can actually determine the ranges that are for the individuals. But here’s where things make sense. But what we’re in general, when you look at this, Mario, what is your take from when we assess this particular type of under fundamental research technology as we can apply to athletes? Your daughters are athletes, right? And do you? What have you used in the past for this?

[00:17:07] Usually, when they go on to programs, I mean, they’re super fit, first of all. So they’re looking more at anywhere between like performance in terms of speed, agility, and sustainability. Right. Like, you know, vertical in terms of explosiveness, those types of things. In the area of recovery and energy. This is where I can tell you with the girls and even the boys, they really focused on the energy consistency. Ok. And I can see even with this, which is critical that the phase angle, again, the lower the phase angle, it shows the inability of the cell to store, you know, energy.

[00:18:09] So that’s why that storage of energy, Alex, is real critical because why that is where we get the maximum output and everyone is talking about performance and performance is about what, output. So if that cell can not store the energy, it cannot release the energy and perform. So that’s how nice these are nice markers. I would say that with the latest technology, we need to use them. We need to use them and we need to have benchmarks where it’s not just generalities. A lot of times we talk about generalities. How do you doing? I’m doing good. You know, I had a good workout. Well, what does it mean to you to have a good workout? And what does it mean to have a great workout? The difference is, show me proof. Show me results. It’s all about results. So the better, I guess a good takeaway. A good, good. Kind of, you know, assessment for people. Look at number one. Go to a professional and get your BMR and BMI done. That’s number one. And use the equipment.

[00:19:26] And the specifics so you can mark and you can assess them afterward.

[00:19:34] If you don’t have a straight baseline of pre, you will not have a post. And this is the same thing in performance. If you don’t have your electronic time and track your pre, then your post is meaningless. You really don’t know where you’re going. So for a lot of the performance, you know, to me, life is performance. You’re going to have to perform either at work or at home or you’re going to perform on the field, whatever that may be. On a mat. On a field, you know, in your sports. It’s about keeping track of markers, your pre and post. That way, you know where you’re going and you know your performance in our world. We love scores. Just imagine, go into a game and you never have a score. We don’t keep score. We just want to have fun. It doesn’t. It’s not fun anymore. Right. So.

[00:20:34] So for the things that we’re covering today in terms of the instruments, the methods of measuring body composition all the way from professional, DEXA and water displacement and body pods to skin folds, you know, everyday use, that you can just buy it at your local Wal-Mart anywhere and do the count protest.

[00:21:02] That’s a great baseline.

[00:21:06] And with a lot of the trainers, make sure that when you are training with someone, make sure that they do a baseline so you know and they know where you’re at and the performance and the programming.

[00:21:23] It’s really important to understand programming. There has to be a scaling. There has to be a periodicity in that development. And I know when little Alex was training for state, you know, in the wrestling, there has to be a periodicity. You can’t just go hard and go home like everybody says. No. You have to have your point of performance and you’ve got to have your track, your flow to that. Just like when Mia is training for nationals or international competition in tennis, there has to be a plan where she is developing to peak at that time. Is that correct? Yes, yes, yes, yes. That’s so critical. And we, you, cannot create that plan to peak at that specific if you’re in the dark in terms of having a knowledge of where you’re at. And I think for our listeners and our viewers, it’s critical and it’s very, very easy to get. I think sometimes people get lost, like all, you know, BMI. I would venture to say 80 percent of the people that are listening today. Right. That are watching this video. Have no clue what BMI means. They’ve heard about it, but they have no clue what it is. Yeah, they think it’s some scientific something. No, it’s not. All right. We want to bring it down to earth, down into your living room, where you can actually do a BMI for your kids, right? Yeah. Why don’t we do that? Why don’t we do a BMI for your kids? Do it for your husband, your wife. Make sure you know where you’re at again, with a BMI. And this, you know, refresh my memory. The target is from 19 to 20. Ok, 19 to 20. Anything beyond that is obesity. If you’re talking about 25 BMI, you’re in the obesity range. Right. If you’re talking about 30, you are morbidly obese. And the word morbidly obese means death. That should get everyone’s attention. Oh, yes. Yes, it does. It kinda like wakes you up. So what we’re looking at is, number one, understand where you are. Then measurements and then also understand that these measurements fit the profile of a person. So if you’re a bodybuilder, if you are very heavy muscle-bound. Ok. Then you already know you need to go into impedance. Not measurements. But what I have found out. A very reliable measurement is. The measurement for your waist and that’s where, Alex, I want to kind of share this with our listeners and viewers. Just a simple waist measurement is so powerful because it is actually…

[00:24:24] Some people say it’s better than BMI. It sure is. Right. I mean, actually, yes, it’s yes, it’s very much. That waist measurement gets down and makes it so simple because that abdominal mass, that abdominal fat is the one that’s gonna kill you.

[00:24:41] That’s the one that has the highest risk. Is that correct?

[00:24:44] That’s correct. And if your belly is wide. If it sticks over your belt, we got issues. Ok. So we’re noticing that if there is a certain distance between the chest and the waist, those are better measurements in general. Yeah. So as those numbers are calculated, you don’t need a high-level test. To do this. Ok. I like that. So it’s a very important component to look at. But as we advance and we’re dealing with high-performance athletes, people want to know and you can take a sport like, let’s say, just wrestling, for example, you got these individuals. Or soccer. Huge. We’re dealing with to assess a tight BMI or in a tight body mass index. You got to have body fat. You got to have body fat to be able to sustain the loads of an exercise routine. You’re going to see that during season you got some guys that got some good body fat density. Right. And let’s say their weight class is 198, for example. And the guy is about 215 pounds. Well, if he drops from 215 to 198 overnight, he’s going to be exorbitantly exhausted. And this is something that we’re going to see now if he slowly works towards the goal towards the arena of 198 over a period of two weeks. Or he is better off. But let’s assume he gets there to the exact bodyweight 198 and its 3 days before competition, right? It’s going to be exhausting. He’s gonna be tired. However, if he can get there two weeks earlier and adapt his body as his body starts getting better, it will be able to respond better during the loads that it needs.

[00:26:31] And this is what we are talking about, that it needs to be sports specific. You follow me Alex? Exactly. So that same conversation cannot be held with a soccer player. Exactly. A football player and a tennis player or anything in that what I call long aerobics exertion of over, you know, over, let’s say 10, 15 minutes. And this is what’s happening is and I love it when you said that example with wrestlers, you know, I would say the same goes towards MMA fighters, which I take care of. Yes. MMA fighters in Phoenix and in different areas that then you’re talking about also boxers. Again, they have to make weight. Yes. Ok. Though the world of making weight is a beast, that is a world where you have to be on or you’re going to die. Exactly. You either go into that fight feeling like a beast or you’re praying that it ends quickly. And so. Yeah. Yeah. You gotta pin him in the first 10 seconds. Yes. So. So this is where it’s so important that the training, the measurements, the analytics, and metrics. We’re in a world of analytics and metrics, Alex. We’re not in a world of. Oh, he looks good.

[00:28:09] No, no, we’re past that. We’re way past. No, Mario, we’re in the world of making sure that when we wait, when we compare the athlete, we can measure their changes. And every stage down the road as they compete, as they become more and more in tune to that moment of competition, their body changes, their bodies adapt, their bodies become more refined. And as the season gets better or further along in the season, towards the competitions, towards the season, towards the heavy loads. Yeah. That’s when we can kind of see how the body’s changing. So these tests can actually help us determine how the body reacts. And once these competitors have years of competing and during those years they have offseason and on the season and we need to be able to measure those things in an easy way. That’s what these tests do in terms of tennis, for example, when you’ve done these kind of things. What have you noticed in terms of, let’s say, just the athlete of tennis or even the boxers that you deal with? What have you noticed in terms of the, specifically the…

[00:29:15] Progression through the season. It’s critical, it’s critical and Alex, I can tell you this, that it’s not just performance. The other conversation that I think really needs to be. Dialed in is recovery, recovery, Alex. Ok. And the other one that fits together with recovery is the phase angle. Yes. And decreasing injuries. Exactly. That’s where it kind of gets real, real crazy because you can not have this sustainable pattern. Without recovery and without that specificity and knowing when to push it, one to max out, as they say, and when to shut it down or when to go half-speed, and these are conversations that are really, really critical for young athletes. Alex. Yeah, I see a lot of them, you know, and they’re starting nowadays. They’re starting earlier. They’re starting at six and seven years old. Six and seven. I mean, tell your body hasn’t even woke up to the conversation of sports yet. And they are practicing three times a week, having games every weekend, or some of them practice three times a week with one team and then go with another team and practice the other two days just so they can be at their best peak.

[00:30:48] What sports are you dealing with that kids are doing at six or seven?

[00:30:53] They’re running like right now. I have patients that are doing basketball and track at the same time.

[00:31:01] Yeah. And during middle school.

[00:31:05] That’s amazing. This is crazy. Yeah. So this is my question. Our question. We’re here to help the community. We’re here to help the parents because their vision is my little kid’s gonna be a superstar, right. He’s going to sign a D1 contract. UT Austin, Texas tag, guns up, baby. Yeah, guns up or U of A. You have Wildcats wildcat.

[00:31:34] No, you know walk-ins.

[00:31:35] Yes. And I’m thinking you’re not gonna make it past high school. I mean, you’re not gonna make it past Montwood or past Franklin. I mean, you are going to hit the wall so hard, so hard with repetitive traumas. Ok. And so those are the components that to me as a health care provider, as a, you know, a sports functional medicine…

[00:32:05] Cognitive.

[00:32:08] Coach, I mean, I need to teach people this, forget taking care of injuries. I want to teach you so you don’t get injured. It’s critical. And then they go into middle school and high school and there’s no season off. There is no season off.

[00:32:24] So in your opinion, what have you seen these tests do in order to help the parent or the athlete or the individual or the coach, for that matter? Understand, as a form of betterment for them? What do we get out of these tests in terms of the athlete?

[00:32:46] Very simple. There is a time to turn it on and a time to turn it off. Ok. So, you reach your goal, rest. Ok. You’ve done the tournament, recover, get the recovery, get the mind and body to recover, Alex. A lot of times we don’t even think about the mind. Yeah, the mind gets beat up in the war, in the battlefield of performance, the mind gets beat up. Yes. Ok. It affects your sleep pattern. It affects your focus. Emotions, anger management, all of those things. So what I would say is we’re here to share knowledge and tools or health. But most of all, for performance. Yes. So that way. Each child and each person, let’s say you’re not in middle school, high school. Let’s say you’re in your 20s and 30s and 40s. Well, you’re performing for life. And so let’s really invite everyone to learn more to look up BMI, BMR, all of these and incorporate them into their plan of workouts and challenge them and ask them, when’s the last time you got measured? How about that? Yeah.

[00:34:13] When’s the last time? We have to kind of teach people that these tests are not, you know, at any point. Just one test. You have to follow through these tests for a lifetime to see what’s actually going on. If you really have a center where you can go and the BIA tests are so simple now that we and the correlation between the highest level of research show that we’re very, very tight. Less than 1 percent variation from clinical research methods. So we know that the BIA works in terms of extremity inflammation, in terms of joint swelling, in terms of the metabolic processes for the mass density in the…

[00:34:56] In each extremity. So if you have one muscle that is larger on one side as a result of an injury from the other extremity, we’ll be able to see the changes.

[00:35:05] So the studies are very clear now. We use phase angles to determine health. We use fat analysis. We use the changes and the progression during a very athletic era or a very athletic season is very important to be able to determine. So that today we’re starting the children a lot younger. We’re starting them at four, five, six years old as the child has to around 4 years old, as long as he can focus is in long as he can pay attention. That’s when we start him active. So it is wise to start the process of understanding the metabolism methods that we use to calculate body mass index through their ages so that we have a measurement of what’s normal for that particular child. Because what we really have to see is what’s good for that individual. Specific gravity is another method to determine if you’re cutting down too much. But that’s another topic running. This particular issue is, particularly on the body mass index. And what we want to do is we want to bring that to the towns and to El Paso, particularly because we have those research capacities here, specifically the ones that we have liked is, you know, body mass index so InBody is one of the most top used. They use it at UTEP. They use it at the top research centers. And it’s pretty much the standard now. And, you know, and since we use it, it offers us an ability to quickly assess an individual. I’ve been at UTEP. I’ve seen the types that they use and it’s very accurate. And since we’ve seen the research said that it follows now we know that this stuff is very accurate. And specifically, now you can actually assess your own and have it online and the determinant through methods where you can keep up with your child, see what’s going on. Any other ideas, any other comments that you have, Mario, in terms of bringing this logic or this kind of approach to understanding basal metabolic indexes to the public?

[00:37:10] I would say, Alex. Number one, let’s make it very simple. You know, let’s make it very simple. So with that, this is as simple as getting on a scale to see how much you weigh. That’s it. So let’s bring that conversation to everyone so everyone gets a scan. Minimal. Minimal. I would say seasonal every season. You should get a scan. You should get a BMI. You should have you should log it in just like your weight. You know, let’s be functional. Let’s think of ourselves as important as our cars. Right. So. So I look at it as you have a little tag up on your windshield that says oil change, you know. So why don’t we do this? Why don’t we have? And I really challenge everyone listening. And, you know, we’re here because we need to take care of our community. You know, our community is probably one of the highest rates of diabetes in the nation. Ok. And all of that starts… Mario. Mario. Yeah. Yeah.

[00:38:20] I’m sorry. I don’t want to say it, but you have to. There’s a big elephant in the room. But El Paso, our town was considered the fattest, sweatiest town in the whole United States at one point. That sickened me when I heard it. It was a different town. We are much more advanced. There were very few gyms. Now we’re all about fitness. So if we’re gonna be the leaders out there and man, I gotta tell you, we got some beautiful athletes coming out of El Paso now. Absolutely. We are one of the tops. We can put our athletes against the best, even the most. Well-bred. Top schools. So as we compete in those areas, we really want to use the tools that all the other places use in order to assess our athletes, our children, and our high-performance individuals. So it’s very important we do that kind of stuff now because we have the technology. And no longer is El Paso going to be the fattest, sweetest town of the United States. That’s unforgivable. You definitely agree with that.

[00:39:23] So just bring in that and the division that I would like to share. Is that the measurement, the simplicity of just getting your weight and your height is now complemented with a BMI that you understand. You have some goals. It’s 2020. Yeah, yeah. It’s 2020, baby. You know what, 2020 means that let’s do better than last year. Let’s be healthier than last year and let us integrate and have a better understanding and better objective plan for our own health. And with this, I would say this test and the body measurement index is a word and an understanding that needs to be spread throughout families. So the family can talk about that, like, hey, what are we doing? How are we doing? Ok. And then with that, use it accordingly. Ok. Accordingly. To create positive outcomes where there is just to be able to play with your child if you have children. That’s your sport. Your sport is not to sit and watch. Your sport is to participate. Throw the ball. Kick the ball. Run with your child. Or if your child is really into sports. Give him the tools. Give her the best tools. They’re not that expensive. Now they’re available. So that way they can get training that is on point and results that are extraordinary.

[00:41:04] Exactly. I couldn’t have said it better myself. We have the technology. It’s here. This is not the six million dollar man, kind of world or this is not outside of our realm. We can give it to our kids. We can show them, parents become the educators.

[00:41:22] They are the ones that seek out the coaches. They are the ones that are the nutritionist for the children. They are the ones that are the psychologists that every aspect of developing a child requires a lot of different aspects. So those parents that have athletes, athletes that want to learn more about their bodies and the world of heavy tech research methods are over. Now, it’s simple. You get on scale really accurate methods and you can monitor your body a few times a year, two, three, four times a year, depending on your type of sport and your level of performance. These are the things we can do. And we need to provide that information so that you have tools in order to gage.

[00:42:11] You can’t get in a car without looking at a speedometer. So if don’t know how fast you’re going. You don’t know if you’ve gone too far. You don’t know if you’re having protein metabolic catabolism, which is breakdown or if you’re anabolic. So these are the tools that help us figure things out. You don’t know if certain joints or certain extremities are swollen because of just water or if it’s this protein breakdown. These tools we can actually see inside the body and monitor the improvement or changes. So the world changed. So now El Paso, we have the ability to change the way we understand our own physiology as well as the patient’s physiology and our client’s physiology. So I welcome this technology. And by no means is it limited to anything that we do. This is many providers in the town who can do this. Many hospitals have it. But for a facility, it’s within our practices as well. So we use those things. So I look forward to being able to share this with the patients as well as the town.

[00:43:15] Absolutely.

[00:43:16] I second emotion on that, Alex, and the challenge and the motivation and passion that we’re going to have this year in 2020. Absolutely.

[00:43:26] As to not only motivate and be cheerleaders for functional health and fitness, but also to educate and empower the community with the latest technology and knowledge so they can do their best.

[00:43:43] Amen, brother. This is awesome. And I look forward to being able to continue. We’re going to be coming at you often because we’re motivated.

[00:43:53] We’re parents and we want to be able to touch our El Paso and make it a better place because, you know, without getting too crazy, we’re pretty badass, as they say.

[00:44:04] Right. Yeah. We’re pretty intense in our town, right? Yeah.

[00:44:07] Mario. Don’t get me started.

[00:44:11] They’re gonna shut me down. No, no, no, no.

[00:44:16] We won’t do that later, guys. We’ll go ahead and see the show. And it’s been a blessing. So from all of us here, we can actually see how you guys are doing. So. Blessings to you guys. Thank you, guys. Bye-bye.

Additional Topic Discussion: Chronic Pain

Sudden pain is a natural response of the nervous system which helps to demonstrate possible injury. By way of instance, pain signals travel from an injured region through the nerves and spinal cord to the brain. Pain is generally less severe as the injury heals, however, chronic pain is different than the average type of pain. With chronic pain, the human body will continue sending pain signals to the brain, regardless if the injury has healed. Chronic pain can last for several weeks to even several years. Chronic pain can tremendously affect a patient’s mobility and it can reduce flexibility, strength, and endurance.

Neural Zoomer Plus for Neurological Disease

Dr. Alex Jimenez utilizes a series of tests to help evaluate neurological diseases. The Neural ZoomerTM Plus is an array of neurological autoantibodies which offers specific antibody-to-antigen recognition. The Vibrant Neural ZoomerTM Plus is designed to assess an individual�s reactivity to 48 neurological antigens with connections to a variety of neurologically related diseases. The Vibrant Neural ZoomerTM Plus aims to reduce neurological conditions by empowering patients and physicians with a vital resource for early risk detection and an enhanced focus on personalized primary prevention.

Food Sensitivity for the IgG & IgA Immune Response

Dr. Alex Jimenez utilizes a series of tests to help evaluate health issues associated with a variety of food sensitivities and intolerances. The Food Sensitivity ZoomerTM is an array of 180 commonly consumed food antigens that offers very specific antibody-to-antigen recognition. This panel measures an individual�s IgG and IgA sensitivity to food antigens. Being able to test IgA antibodies provides additional information to foods that may be causing mucosal damage. Additionally, this test is ideal for patients who might be suffering from delayed reactions to certain foods. Utilizing an antibody-based food sensitivity test can help prioritize the necessary foods to eliminate and create a customized diet plan around the patient�s specific needs.

Gut Zoomer for Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO)

Dr. Alex Jimenez utilizes a series of tests to help evaluate gut health associated with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO). The Vibrant Gut ZoomerTM offers a report that includes dietary recommendations and other natural supplementation like prebiotics, probiotics, and polyphenols. The gut microbiome is mainly found in the large intestine and it has more than 1000 species of bacteria that play a fundamental role in the human body, from shaping the immune system and affecting the metabolism of nutrients to strengthening the intestinal mucosal barrier (gut-barrier). It is essential to understand how the number of bacteria that symbiotically live in the human gastrointestinal (GI) tract influences gut health because imbalances in the gut microbiome may ultimately lead to gastrointestinal (GI) tract symptoms, skin conditions, autoimmune disorders, immune system imbalances, and multiple inflammatory disorders.

Formulas for Methylation Support

XYMOGEN�s Exclusive Professional Formulas are available through select licensed health care professionals. The internet sale and discounting of XYMOGEN formulas are strictly prohibited.

Proudly,�Dr. Alexander Jimenez makes XYMOGEN formulas available only to patients under our care.

Please call our office in order for us to assign a doctor consultation for immediate access.

If you are a patient of Injury Medical & Chiropractic�Clinic, you may inquire about XYMOGEN by calling 915-850-0900.

For your convenience and review of the XYMOGEN products please review the following link. *XYMOGEN-Catalog-Download

* All of the above XYMOGEN policies remain strictly in force.

Modern Integrated Medicine

The National University of Health Sciences is an institution that offers a variety of rewarding professions to attendees. Students can practice their passion for helping other people achieve overall health and wellness through the institution’s mission. The National University of Health Sciences prepares students to become leaders in the forefront of modern integrated medicine, including chiropractic care. Students have an opportunity to gain unparalleled experience at the National University of Health Sciences to help restore the natural integrity of the patient and define the future of modern integrated medicine.

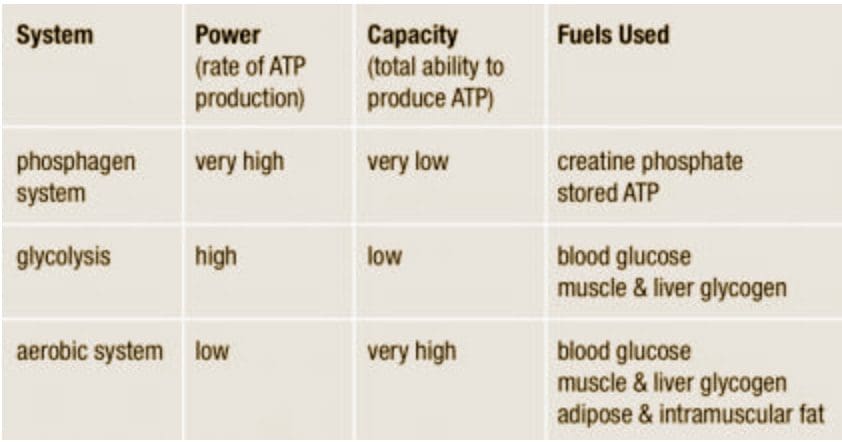

We usually talk of energy in general terms, as in �I don�t have a lot of energy today� or �You can feel the energy in the room.� But what really is energy? Where do we get the energy to move? How do we use it? How do we get more of it? Ultimately, what controls our movements? The three metabolic energy pathways are the�phosphagen system, glycolysis�and the�aerobic system.�How do they work, and what is their effect?

We usually talk of energy in general terms, as in �I don�t have a lot of energy today� or �You can feel the energy in the room.� But what really is energy? Where do we get the energy to move? How do we use it? How do we get more of it? Ultimately, what controls our movements? The three metabolic energy pathways are the�phosphagen system, glycolysis�and the�aerobic system.�How do they work, and what is their effect? The energy for all physical activity comes from the conversion of high-energy phosphates (adenosine�triphosphate�ATP) to lower-energy phosphates (adenosine�diphosphate�ADP; adenosine�monophosphate�AMP; and inorganic phosphate, Pi). During this breakdown (hydrolysis) of ATP, which is a water-requiring process, a proton, energy and heat are produced: ATP + H2O ���ADP + Pi�+ H+�+ energy + heat. Since our muscles don�t store much ATP, we must constantly resynthesize it. The hydrolysis and resynthesis of ATP is thus a circular process�ATP is hydrolyzed into ADP and Pi, and then ADP and Pi�combine to resynthesize ATP. Alternatively, two ADP molecules can combine to produce ATP and AMP: ADP + ADP ���ATP + AMP.

The energy for all physical activity comes from the conversion of high-energy phosphates (adenosine�triphosphate�ATP) to lower-energy phosphates (adenosine�diphosphate�ADP; adenosine�monophosphate�AMP; and inorganic phosphate, Pi). During this breakdown (hydrolysis) of ATP, which is a water-requiring process, a proton, energy and heat are produced: ATP + H2O ���ADP + Pi�+ H+�+ energy + heat. Since our muscles don�t store much ATP, we must constantly resynthesize it. The hydrolysis and resynthesis of ATP is thus a circular process�ATP is hydrolyzed into ADP and Pi, and then ADP and Pi�combine to resynthesize ATP. Alternatively, two ADP molecules can combine to produce ATP and AMP: ADP + ADP ���ATP + AMP. During short-term, intense activities, a large amount of power needs to be produced by the muscles, creating a high demand for ATP. The phosphagen system (also called the ATP-CP system) is the quickest way to resynthesize ATP (Robergs & Roberts 1997). Creatine phosphate (CP), which is stored in skeletal muscles, donates a phosphate to ADP to produce ATP: ADP + CP ���ATP + C. No carbohydrate or fat is used in this process; the regeneration of ATP comes solely from stored CP. Since this process does not need oxygen to resynthesize ATP, it is anaerobic, or oxygen-independent. As the fastest way to resynthesize ATP, the phosphagen system is the predominant energy system used for all-out exercise lasting up to about 10 seconds. However, since there is a limited amount of stored CP and ATP in skeletal muscles, fatigue occurs rapidly.

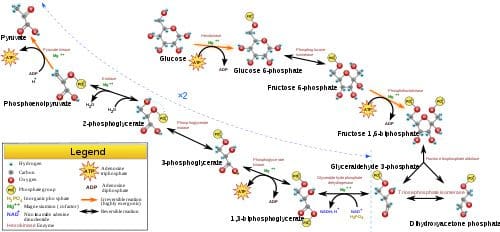

During short-term, intense activities, a large amount of power needs to be produced by the muscles, creating a high demand for ATP. The phosphagen system (also called the ATP-CP system) is the quickest way to resynthesize ATP (Robergs & Roberts 1997). Creatine phosphate (CP), which is stored in skeletal muscles, donates a phosphate to ADP to produce ATP: ADP + CP ���ATP + C. No carbohydrate or fat is used in this process; the regeneration of ATP comes solely from stored CP. Since this process does not need oxygen to resynthesize ATP, it is anaerobic, or oxygen-independent. As the fastest way to resynthesize ATP, the phosphagen system is the predominant energy system used for all-out exercise lasting up to about 10 seconds. However, since there is a limited amount of stored CP and ATP in skeletal muscles, fatigue occurs rapidly. Glycolysis is the predominant energy system used for all-out

Glycolysis is the predominant energy system used for all-out  Since humans evolved for aerobic activities (Hochachka, Gunga & Kirsch 1998; Hochachka & Monge 2000), it�s not surprising that the aerobic system, which is dependent on oxygen, is the most complex of the three energy systems. The metabolic reactions that take place in the presence of oxygen are responsible for most of the cellular energy produced by the body. However, aerobic metabolism is the slowest way to resynthesize ATP. Oxygen, as the patriarch of metabolism, knows that it is worth the wait, as it controls the fate of endurance and is the sustenance of life. �I�m oxygen,� it says to the muscle, with more than a hint of superiority. �I can give you a lot of ATP, but you will have to wait for it.�

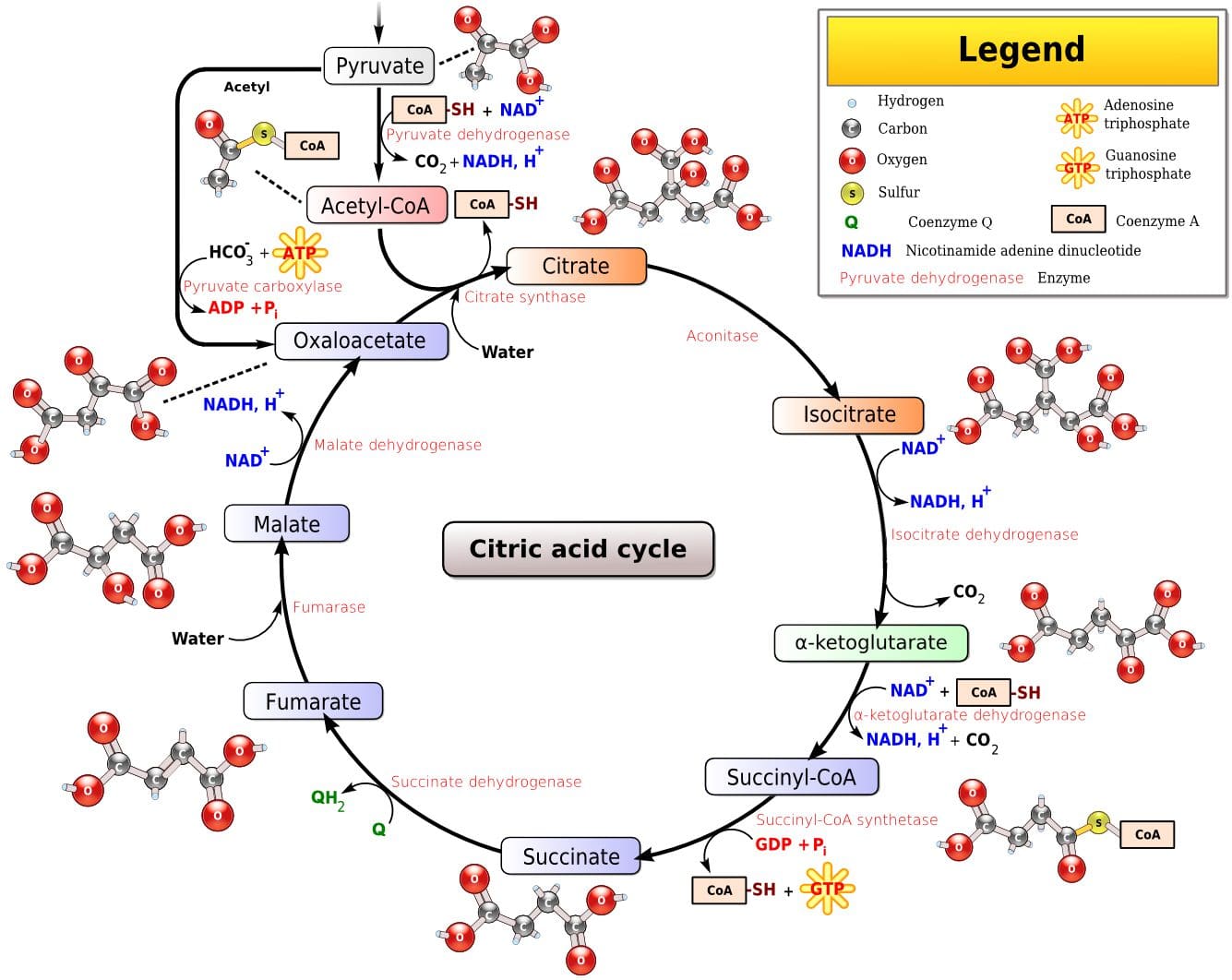

Since humans evolved for aerobic activities (Hochachka, Gunga & Kirsch 1998; Hochachka & Monge 2000), it�s not surprising that the aerobic system, which is dependent on oxygen, is the most complex of the three energy systems. The metabolic reactions that take place in the presence of oxygen are responsible for most of the cellular energy produced by the body. However, aerobic metabolism is the slowest way to resynthesize ATP. Oxygen, as the patriarch of metabolism, knows that it is worth the wait, as it controls the fate of endurance and is the sustenance of life. �I�m oxygen,� it says to the muscle, with more than a hint of superiority. �I can give you a lot of ATP, but you will have to wait for it.� Fat, which is stored as triglyceride in adipose tissue underneath the skin and within skeletal muscles (called�intramuscular triglyceride), is the other major fuel for the aerobic system, and is the largest store of energy in the body. When using fat, triglycerides are first broken down into free fatty acids and glycerol (a process called�lipolysis). The free fatty acids, which are composed of a long chain of carbon atoms, are transported to the muscle mitochondria, where the carbon atoms are used to produce acetyl-CoA (a process called�beta-oxidation).

Fat, which is stored as triglyceride in adipose tissue underneath the skin and within skeletal muscles (called�intramuscular triglyceride), is the other major fuel for the aerobic system, and is the largest store of energy in the body. When using fat, triglycerides are first broken down into free fatty acids and glycerol (a process called�lipolysis). The free fatty acids, which are composed of a long chain of carbon atoms, are transported to the muscle mitochondria, where the carbon atoms are used to produce acetyl-CoA (a process called�beta-oxidation).

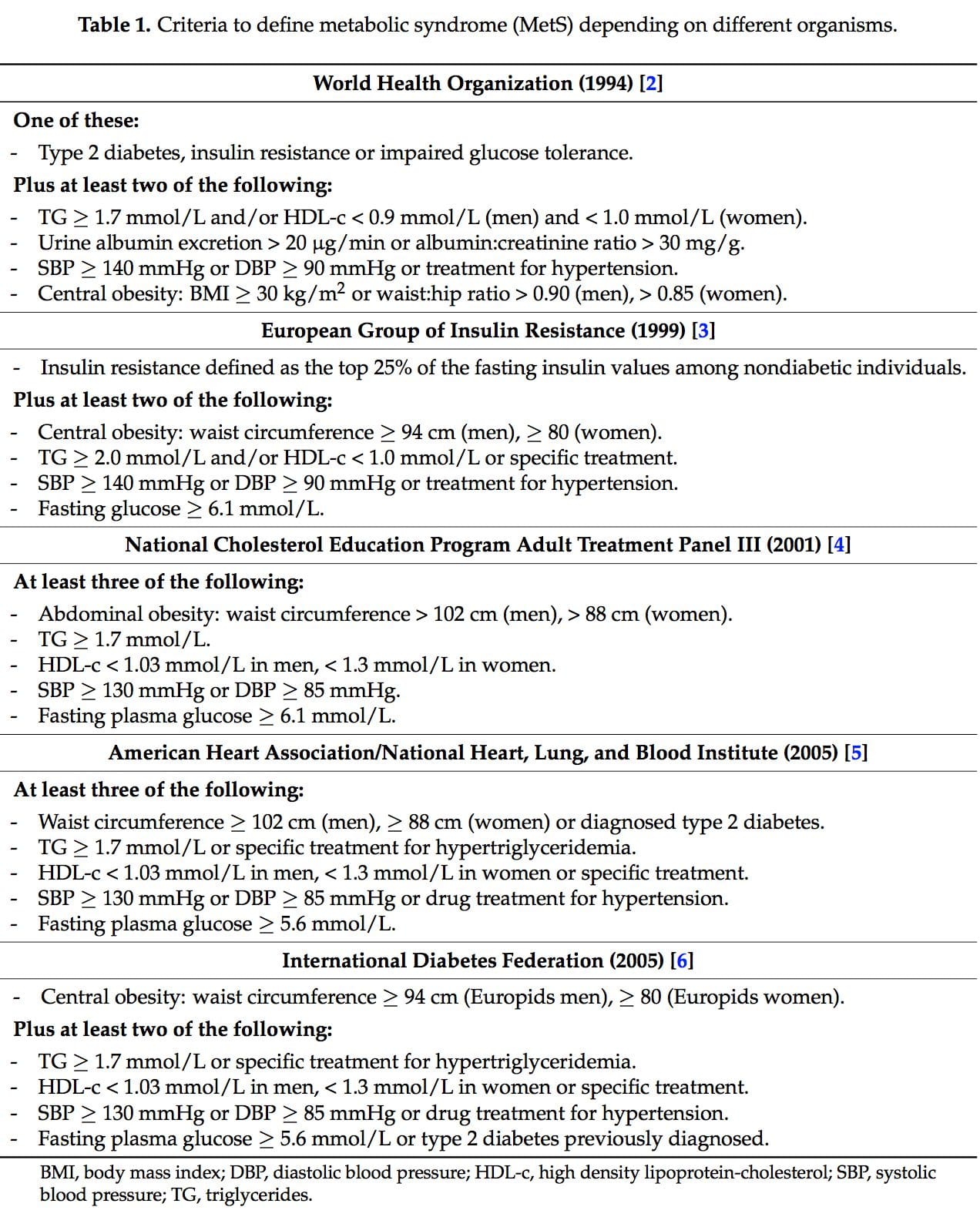

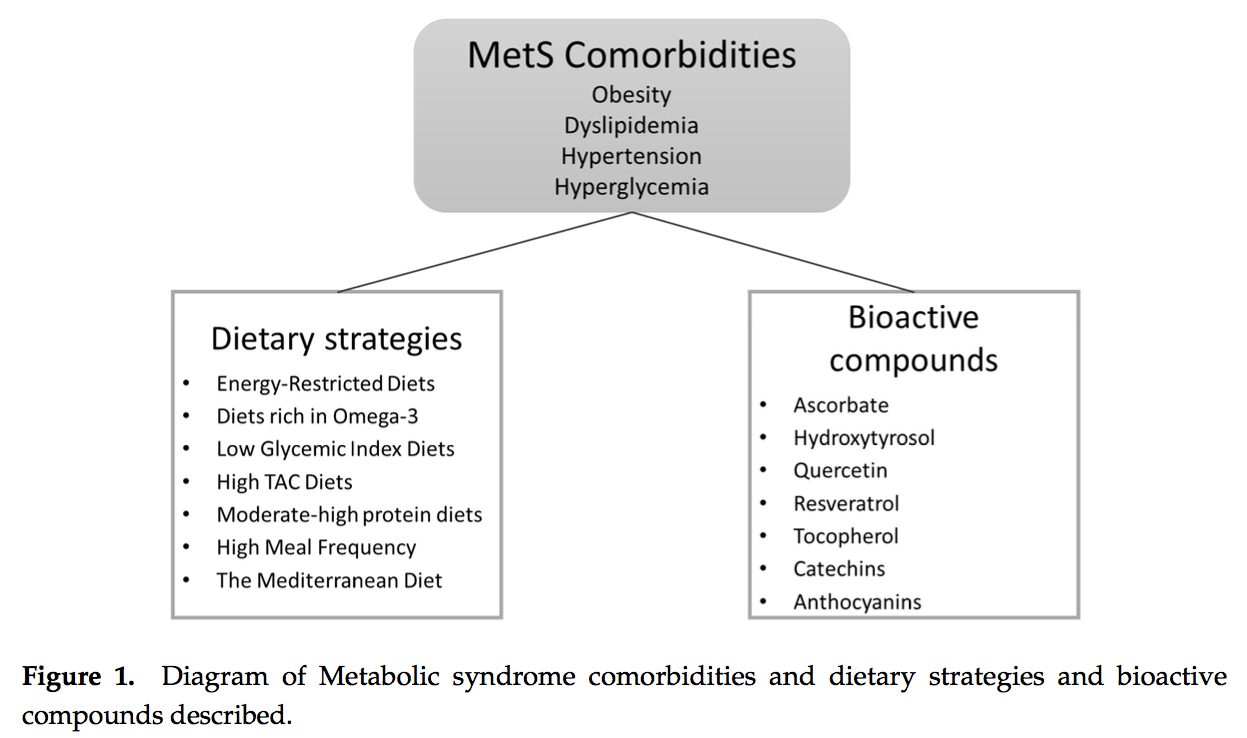

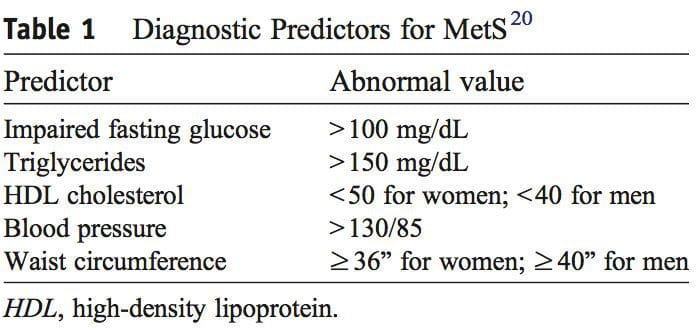

It was during the period between 1910 and 1920 when it was suggested for the first time that a cluster of associated metabolic disturbances tended to coexist together [1]. Since then, different health organisms have suggested diverse definitions for metabolic syndrome (MetS) but there has not yet been a well-established consensus. The most common definitions are summarized in Table 1. What is clear for all of these is that the MetS is a clinical entity of substantial heterogeneity, commonly represented by the combination of obesity (especially abdominal obesity), hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia and/or hypertension [2�6].

It was during the period between 1910 and 1920 when it was suggested for the first time that a cluster of associated metabolic disturbances tended to coexist together [1]. Since then, different health organisms have suggested diverse definitions for metabolic syndrome (MetS) but there has not yet been a well-established consensus. The most common definitions are summarized in Table 1. What is clear for all of these is that the MetS is a clinical entity of substantial heterogeneity, commonly represented by the combination of obesity (especially abdominal obesity), hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia and/or hypertension [2�6].

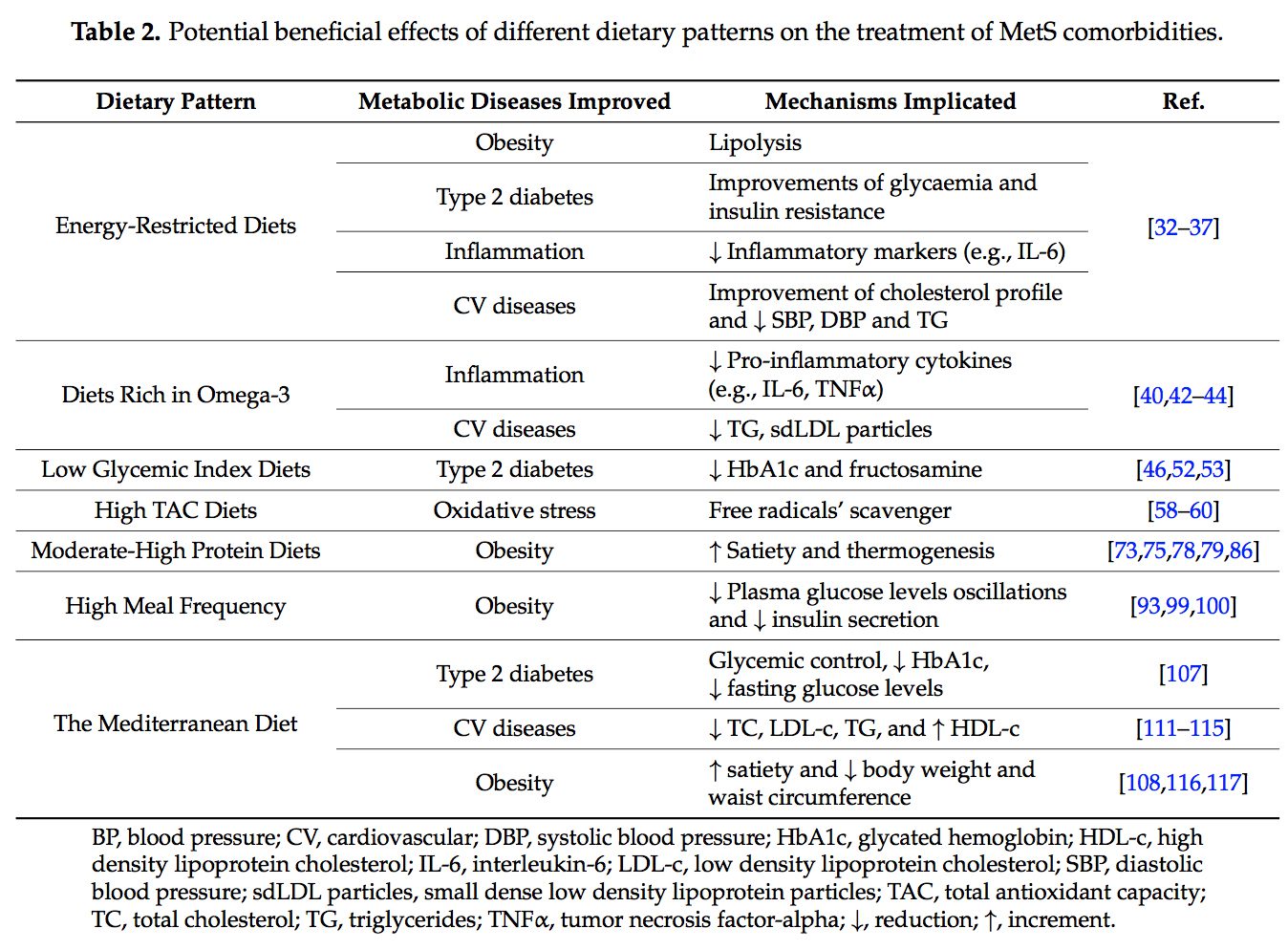

Several dietary strategies and their potential positive effects on the prevention and treatment of the different metabolic complications associated to the MetS, are described below and summarized in Table 2.

Several dietary strategies and their potential positive effects on the prevention and treatment of the different metabolic complications associated to the MetS, are described below and summarized in Table 2. 2.1. Energy-Restricted Diet Strategies

2.1. Energy-Restricted Diet Strategies

The very long-chain eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) are essential omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFAs) for human physiology. Their main dietary sources are fish and algal oils and fatty fish, but they can also be synthesized by humans from ?-linolenic acid [40].

The very long-chain eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) are essential omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFAs) for human physiology. Their main dietary sources are fish and algal oils and fatty fish, but they can also be synthesized by humans from ?-linolenic acid [40]. Over the last ten years, the concern about the quality of the carbohydrates (CHO) consumed has risen [46]. In this context, the glycemic index (GI) is used as a CHO quality measure. It consists in a ranking on a scale from 0 to 100 that classifies carbohydrate-containing foods according to the postprandial glucose response [47]. The higher the index, the more promptly the postprandial serum glucose rises and the more rapid the insulin response. A quick insulin response leads to rapid hypoglycemia, which is suggested to be associated with an increment of the feeling of hunger and to a subsequent higher caloric intake [47]. The glycemic load (GL) is equal to the GI multiplied by the number of grams of CHO in a serving [48].

Over the last ten years, the concern about the quality of the carbohydrates (CHO) consumed has risen [46]. In this context, the glycemic index (GI) is used as a CHO quality measure. It consists in a ranking on a scale from 0 to 100 that classifies carbohydrate-containing foods according to the postprandial glucose response [47]. The higher the index, the more promptly the postprandial serum glucose rises and the more rapid the insulin response. A quick insulin response leads to rapid hypoglycemia, which is suggested to be associated with an increment of the feeling of hunger and to a subsequent higher caloric intake [47]. The glycemic load (GL) is equal to the GI multiplied by the number of grams of CHO in a serving [48]. Dietary total antioxidant capacity (TAC) is an indicator of diet quality defined as the sum of antioxidant activities of the pool of antioxidants present in a food [55]. These antioxidants have the capacity to act as scavengers of free radicals and other reactive species produced in the organisms [56]. Taking into account that oxidative stress is one of the remarkable unfortunate physiological states of MetS, dietary antioxidants are of main interest in the prevention and treatment of this multifactorial disorder [57]. Accordingly, it is well-accepted that diets with a high content of spices, herbs, fruits, vegetables, nuts and chocolate, are associated with a decreased risk of oxidative stress-related diseases development [58�60]. Moreover, several studies have analyzed the effects of dietary TAC in individuals suffering from MetS or related diseases [61,62]. In the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study it was demonstrated that a high TAC has beneficial effects on metabolic disorders and especially prevents weight and abdominal fat gain [61]. In the same line, research conducted in our institutions also evidenced that beneficial effects on body weight, oxidative stress biomarkers and other MetS features were positively related with higher TAC consumption in patients suffering from MetS [63�65].

Dietary total antioxidant capacity (TAC) is an indicator of diet quality defined as the sum of antioxidant activities of the pool of antioxidants present in a food [55]. These antioxidants have the capacity to act as scavengers of free radicals and other reactive species produced in the organisms [56]. Taking into account that oxidative stress is one of the remarkable unfortunate physiological states of MetS, dietary antioxidants are of main interest in the prevention and treatment of this multifactorial disorder [57]. Accordingly, it is well-accepted that diets with a high content of spices, herbs, fruits, vegetables, nuts and chocolate, are associated with a decreased risk of oxidative stress-related diseases development [58�60]. Moreover, several studies have analyzed the effects of dietary TAC in individuals suffering from MetS or related diseases [61,62]. In the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study it was demonstrated that a high TAC has beneficial effects on metabolic disorders and especially prevents weight and abdominal fat gain [61]. In the same line, research conducted in our institutions also evidenced that beneficial effects on body weight, oxidative stress biomarkers and other MetS features were positively related with higher TAC consumption in patients suffering from MetS [63�65]. The macronutrient distribution set in a weight loss dietary plan has commonly been 50%�55% total caloric value from CHO, 15% from proteins and 30% from lipids [57,68]. However, as most people have difficulty in maintaining weight loss achievements over time [69,70], research on increment of protein intake (>20%) at the expense of CHO was carried out [71�77].

The macronutrient distribution set in a weight loss dietary plan has commonly been 50%�55% total caloric value from CHO, 15% from proteins and 30% from lipids [57,68]. However, as most people have difficulty in maintaining weight loss achievements over time [69,70], research on increment of protein intake (>20%) at the expense of CHO was carried out [71�77].

The concept of the

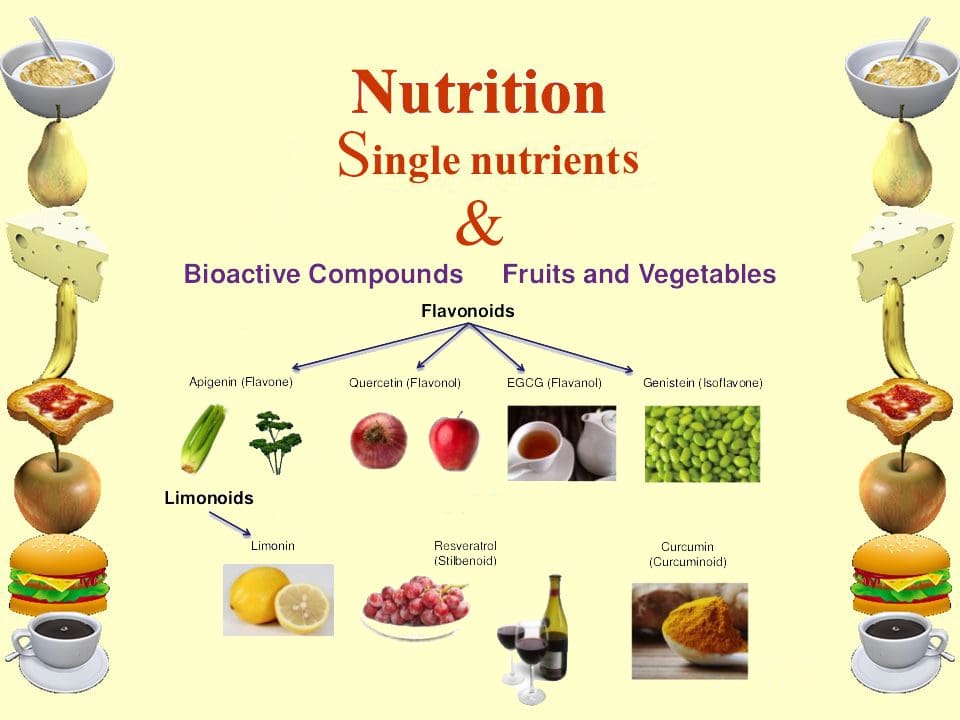

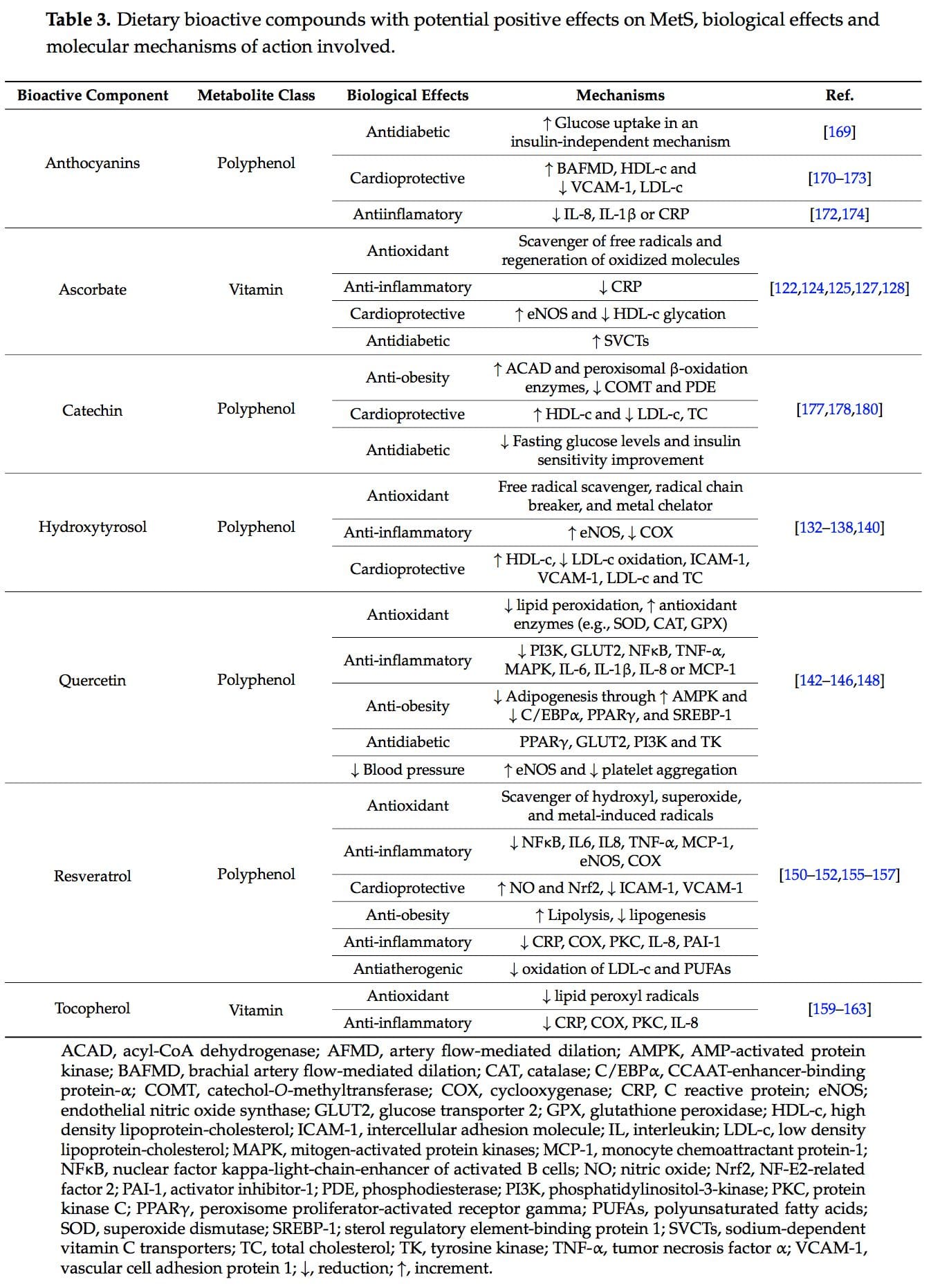

The concept of the  New studies focused on the molecular action of nutritional bioactive compounds with positive effects on MetS are currently an objective of scientific research worldwide with the aim of designing more personalized strategies in the framework of molecular nutrition. Among them, flavonoids and antioxidant vitamins are some of the most studied compounds with different potential benefits such as antioxidant, vasodilatory, anti-atherogenic, antithrombotic, and anti-inflammatory effects [119]. Table 3 summarizes different nutritional bioactive compounds with potential positive effects on MetS, including the possible molecular mechanism of action involved.

New studies focused on the molecular action of nutritional bioactive compounds with positive effects on MetS are currently an objective of scientific research worldwide with the aim of designing more personalized strategies in the framework of molecular nutrition. Among them, flavonoids and antioxidant vitamins are some of the most studied compounds with different potential benefits such as antioxidant, vasodilatory, anti-atherogenic, antithrombotic, and anti-inflammatory effects [119]. Table 3 summarizes different nutritional bioactive compounds with potential positive effects on MetS, including the possible molecular mechanism of action involved.

Vitamin C, ascorbic acid or ascorbate is an essential nutrient as human beings cannot synthesize it. It is a water-soluble antioxidant mainly found in fruits, especially citrus (lemon, orange), and vegetables (pepper, kale) [120]. Several beneficial effects have been associated to this vitamin such as antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties and prevention or treatment of CVD and type 2 diabetes [121�123].

Vitamin C, ascorbic acid or ascorbate is an essential nutrient as human beings cannot synthesize it. It is a water-soluble antioxidant mainly found in fruits, especially citrus (lemon, orange), and vegetables (pepper, kale) [120]. Several beneficial effects have been associated to this vitamin such as antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties and prevention or treatment of CVD and type 2 diabetes [121�123]. Hydroxytyrosol (3,4-dihydroxyphenylethanol) is a phenolic compound mainly found in olives [132].

Hydroxytyrosol (3,4-dihydroxyphenylethanol) is a phenolic compound mainly found in olives [132]. Quercetin is a predominant flavanol naturally present in vegetables, fruits, green tea or red wine. It is commonly found as glycoside forms, where rutin is the most common and important structure found in nature [141].

Quercetin is a predominant flavanol naturally present in vegetables, fruits, green tea or red wine. It is commonly found as glycoside forms, where rutin is the most common and important structure found in nature [141].

Tocopherols, also known as vitamin E, are a family of eight fat-soluble phenolic compounds whose main dietary sources are vegetable oils, nuts and seeds [130,158].

Tocopherols, also known as vitamin E, are a family of eight fat-soluble phenolic compounds whose main dietary sources are vegetable oils, nuts and seeds [130,158].

Catechins are polyphenols that can be found in a variety of foods including fruits, vegetables, chocolate, wine, and tea [175]. The epigallocatechin 3-gallate present in tea leaves is the catechin class most studied [176].

Catechins are polyphenols that can be found in a variety of foods including fruits, vegetables, chocolate, wine, and tea [175]. The epigallocatechin 3-gallate present in tea leaves is the catechin class most studied [176].

PubMed was searched from the earliest possible date to May 2014 to identify review articles that outlined the pathophysiology of MetS and T2DM. This led to further search refinements to identify inflammatory mechanisms that occur in the pancreas, adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, and hypothalamus. Searches were also refined to identify relationships among diet, supplements, and glycemic regulation. Both animal and human studies were reviewed. The selection of specific supplements was based on those that were most commonly used in the clinical setting, namely, gymnema sylvestre, vanadium, chromium and ?-lipoic acid.

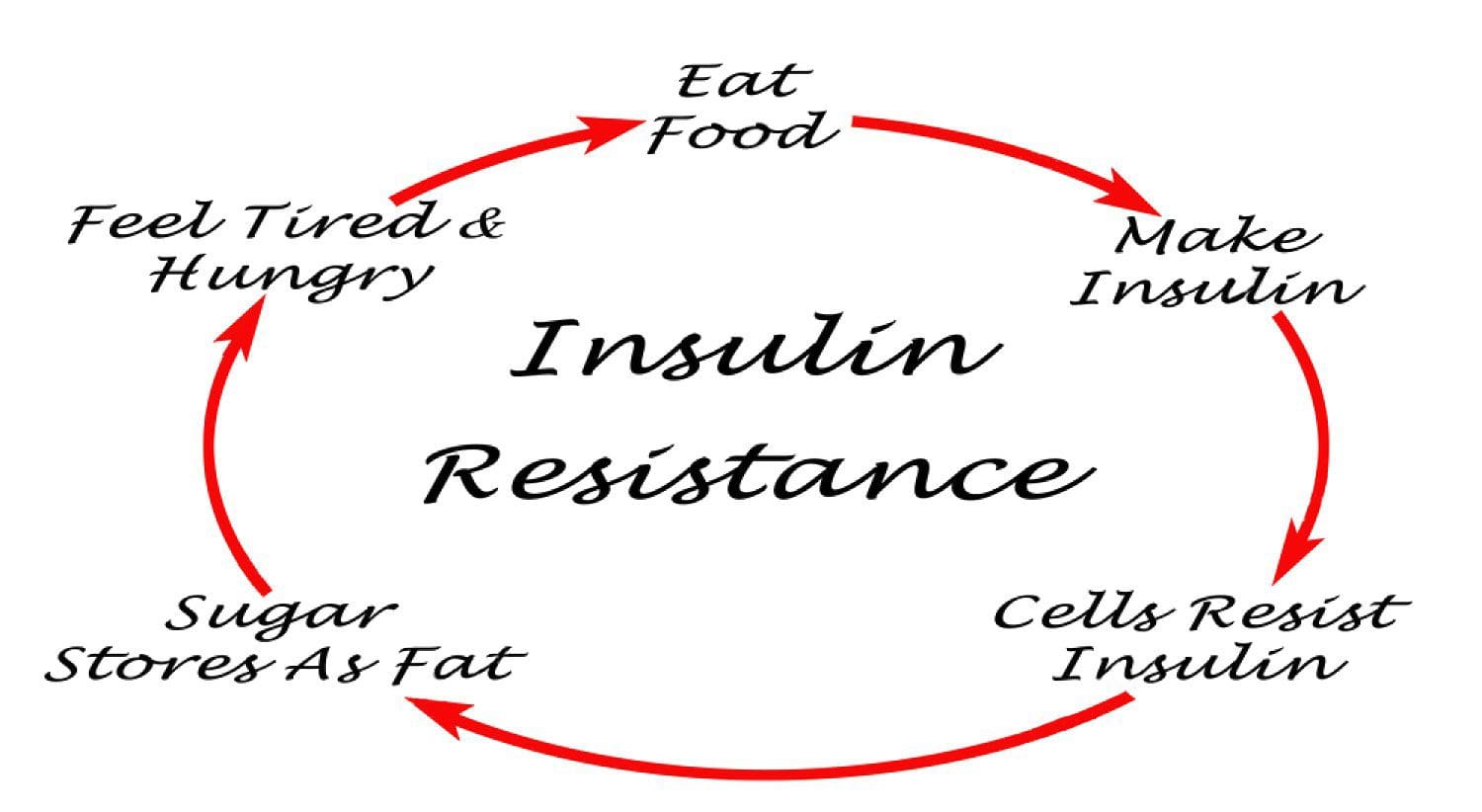

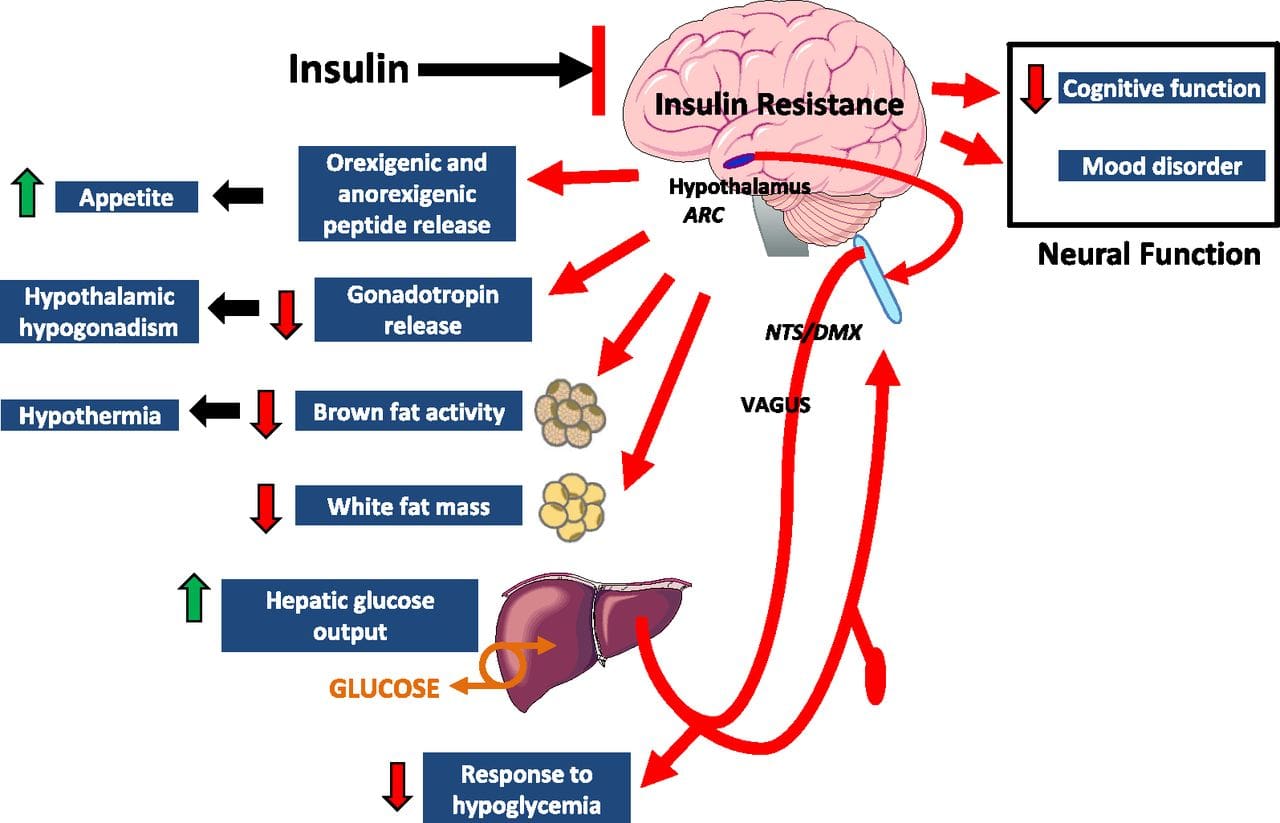

PubMed was searched from the earliest possible date to May 2014 to identify review articles that outlined the pathophysiology of MetS and T2DM. This led to further search refinements to identify inflammatory mechanisms that occur in the pancreas, adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, and hypothalamus. Searches were also refined to identify relationships among diet, supplements, and glycemic regulation. Both animal and human studies were reviewed. The selection of specific supplements was based on those that were most commonly used in the clinical setting, namely, gymnema sylvestre, vanadium, chromium and ?-lipoic acid. Under normal conditions, skeletal muscle, hepatic, and adipose tissues require the action of insulin for cellular glucose entry. Insulin resistance represents an inability of insulin to signal glucose passage into insulin-dependent cells. Although a genetic predisposition can exist, the�etiology of insulin resistance has been linked to chronic low-grade inflammation.1 Combined with insulin resistance-induced hyperglycemia, chronic low-grade inflammation also sustains MetS pathophysiology.1

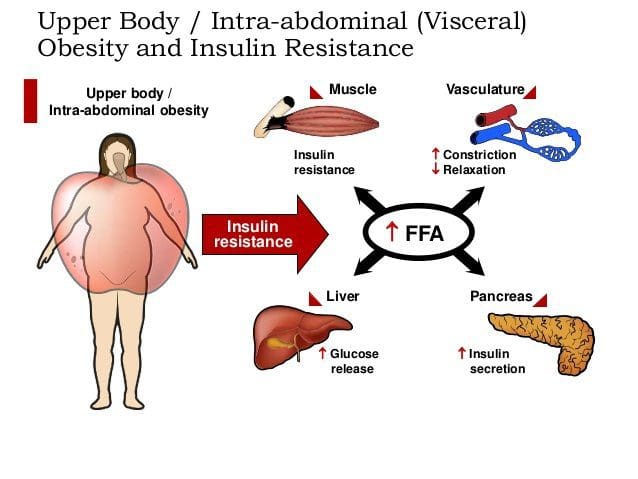

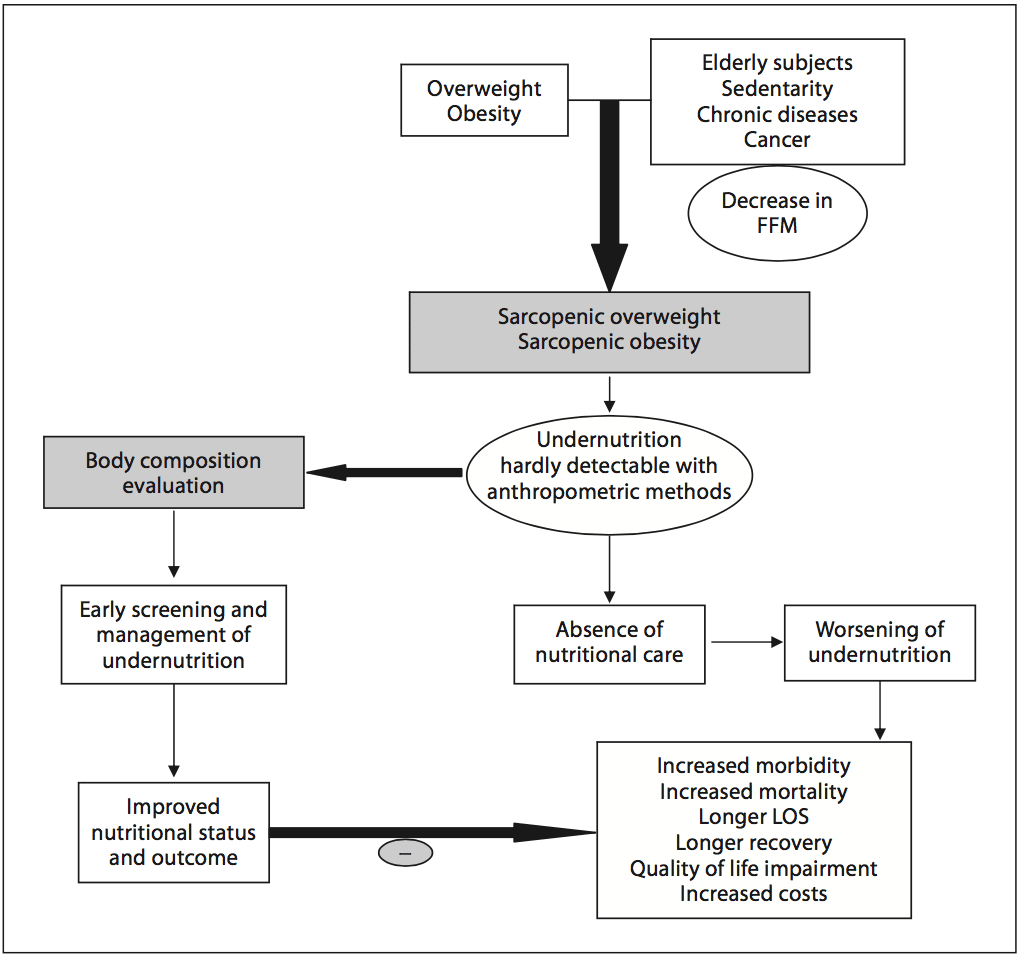

Under normal conditions, skeletal muscle, hepatic, and adipose tissues require the action of insulin for cellular glucose entry. Insulin resistance represents an inability of insulin to signal glucose passage into insulin-dependent cells. Although a genetic predisposition can exist, the�etiology of insulin resistance has been linked to chronic low-grade inflammation.1 Combined with insulin resistance-induced hyperglycemia, chronic low-grade inflammation also sustains MetS pathophysiology.1 Caloric excess and a sedentary lifestyle contribute to the accumulation of subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue. Adipose tissue was once thought of as a metabolically inert passive energy depot. A large body of evidence now demonstrates that excess visceral adipose tissue acts as a driver of chronic low-grade inflammation and insulin resistance.27,34

Caloric excess and a sedentary lifestyle contribute to the accumulation of subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue. Adipose tissue was once thought of as a metabolically inert passive energy depot. A large body of evidence now demonstrates that excess visceral adipose tissue acts as a driver of chronic low-grade inflammation and insulin resistance.27,34 Eating behavior in the obese and overweight has been popularly attributed to a lack of will power or genetics. However, recent research has demonstrated a link between hypothalamic inflammation and increased body weight.41,41

Eating behavior in the obese and overweight has been popularly attributed to a lack of will power or genetics. However, recent research has demonstrated a link between hypothalamic inflammation and increased body weight.41,41 Feeding generally leads to a short-term increase in both oxidative stress and inflammation. 41 Total�calories consumed, glycemic index, and fatty acid profile of a meal all influence the degree of postprandial inflammation. It is estimated that the average American consumes approximately 20% of calories from refined sugar, 20% from refined grains and flour, 15% to 20% from excessively fatty meat products, and 20% from refined seed/legume oils.45 This pattern of eating contains a macronutrient composition and glycemic index that promote hyperglycemia, hyperlipemia, and an acute postprandial inflammatory response. 46 Collectively referred to as postprandial dysmetabolism, this pro-inflammatory response can sustain levels of chronic low-grade inflammation that leads to excess body fat, coronary heart disease (CHD), insulin resistance, and T2DM.28,29,47

Feeding generally leads to a short-term increase in both oxidative stress and inflammation. 41 Total�calories consumed, glycemic index, and fatty acid profile of a meal all influence the degree of postprandial inflammation. It is estimated that the average American consumes approximately 20% of calories from refined sugar, 20% from refined grains and flour, 15% to 20% from excessively fatty meat products, and 20% from refined seed/legume oils.45 This pattern of eating contains a macronutrient composition and glycemic index that promote hyperglycemia, hyperlipemia, and an acute postprandial inflammatory response. 46 Collectively referred to as postprandial dysmetabolism, this pro-inflammatory response can sustain levels of chronic low-grade inflammation that leads to excess body fat, coronary heart disease (CHD), insulin resistance, and T2DM.28,29,47 Diagnosis of MetS has been linked to an increased risk of developing T2DM and cardiovascular disease over the following 5 to 10 years. 1 It further increases a patient’s risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, and death from any of the aforementioned conditions.1

Diagnosis of MetS has been linked to an increased risk of developing T2DM and cardiovascular disease over the following 5 to 10 years. 1 It further increases a patient’s risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, and death from any of the aforementioned conditions.1 Research has identified nutrients that play key roles in promoting proper insulin sensitivity, including vitamin D, magnesium, omega-3 (n-3) fatty acids, curcumin, gymnema, vanadium, chromium, and ?-lipoic acid. It is possible to get adequate vitamin D from sun exposure and adequate amounts of magnesium and omega-3 fatty acids from food. Contrastingly, the therapeutic levels of chromium and ?-lipoic acid that affect insulin sensitivity and reduce�insulin resistance cannot be obtained in food and must be supplemented.

Research has identified nutrients that play key roles in promoting proper insulin sensitivity, including vitamin D, magnesium, omega-3 (n-3) fatty acids, curcumin, gymnema, vanadium, chromium, and ?-lipoic acid. It is possible to get adequate vitamin D from sun exposure and adequate amounts of magnesium and omega-3 fatty acids from food. Contrastingly, the therapeutic levels of chromium and ?-lipoic acid that affect insulin sensitivity and reduce�insulin resistance cannot be obtained in food and must be supplemented. Vitamin D, magnesium, and n-3 fatty acids have multiple functions, and generalized inflammation reduction is a common mechanism of action.74�80 Their supplemental use should be considered in the context of low-grade inflammation reduction and health promotion, rather than as a specific treatment for MetS or T2DM.

Vitamin D, magnesium, and n-3 fatty acids have multiple functions, and generalized inflammation reduction is a common mechanism of action.74�80 Their supplemental use should be considered in the context of low-grade inflammation reduction and health promotion, rather than as a specific treatment for MetS or T2DM. Gymnemic acids are the active component of the G sylvestre plant leaves. Gymnemic acids are the active component of the G sylvestre plant leaves. Studies evaluating G sylvestre’s effects on diabetes in humans have generally been of poor methodological quality. Experimental animal studies have found that gymnemic acids may decrease glucose uptake in the small intestine, inhibit gluconeogenesis, and reduce hepatic and skeletal muscle insulin resistance.99 Other animal studies suggest that gymnemic acids may have comparable efficacy in reducing blood sugar levels to the first-generation sulfonylurea, tolbutamide.100

Gymnemic acids are the active component of the G sylvestre plant leaves. Gymnemic acids are the active component of the G sylvestre plant leaves. Studies evaluating G sylvestre’s effects on diabetes in humans have generally been of poor methodological quality. Experimental animal studies have found that gymnemic acids may decrease glucose uptake in the small intestine, inhibit gluconeogenesis, and reduce hepatic and skeletal muscle insulin resistance.99 Other animal studies suggest that gymnemic acids may have comparable efficacy in reducing blood sugar levels to the first-generation sulfonylurea, tolbutamide.100 Vanadyl sulfate has been reported to prolong the events of insulin signaling and may actually improve insulin sensitivity.101 Limited data suggest that it inhibits gluconeogenesis, possibly ameliorating hepatic insulin resistance. 100,101 Uncontrolled clinical trials have reported improvements in insulin sensitivity using 50 to 300 mg daily for periods ranging from 3 to 6 weeks. 101�103 Contrastingly, a recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial found that 50 mg of vanadyl sulfate twice daily for 4 weeks had no effect in individuals with impaired glucose tolerance. 104 Limited clinical and experimental data exist supporting the use of vanadyl sulfate to improve insulin resistance,�and further research is warranted regarding its safety and efficacy.

Vanadyl sulfate has been reported to prolong the events of insulin signaling and may actually improve insulin sensitivity.101 Limited data suggest that it inhibits gluconeogenesis, possibly ameliorating hepatic insulin resistance. 100,101 Uncontrolled clinical trials have reported improvements in insulin sensitivity using 50 to 300 mg daily for periods ranging from 3 to 6 weeks. 101�103 Contrastingly, a recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial found that 50 mg of vanadyl sulfate twice daily for 4 weeks had no effect in individuals with impaired glucose tolerance. 104 Limited clinical and experimental data exist supporting the use of vanadyl sulfate to improve insulin resistance,�and further research is warranted regarding its safety and efficacy. Diets high in refined sugar and flour are deficient in chromium (Cr) and lead to an increased urinary excretion of chromium. 105,106 The progression of MetS is not likely caused by a chromium deficiency, 107 and dosages that benefit glycemic regulation are not achievable through food. 106,108,109

Diets high in refined sugar and flour are deficient in chromium (Cr) and lead to an increased urinary excretion of chromium. 105,106 The progression of MetS is not likely caused by a chromium deficiency, 107 and dosages that benefit glycemic regulation are not achievable through food. 106,108,109 Humans derive ?-lipoic acid through dietary means and from endogenous synthesis. 111 The foods richest in ?-lipoic acid are animal tissues with extensive metabolic activity such as animal heart, liver, and kidney, which are not consumed in large amounts in the typical American diet. 111 Supplemental amounts of ?-lipoic acid used in the treatment of T2DM (300-600 mg) are likely to be as much as 1000 times greater than the amounts that could be obtained from the diet.112

Humans derive ?-lipoic acid through dietary means and from endogenous synthesis. 111 The foods richest in ?-lipoic acid are animal tissues with extensive metabolic activity such as animal heart, liver, and kidney, which are not consumed in large amounts in the typical American diet. 111 Supplemental amounts of ?-lipoic acid used in the treatment of T2DM (300-600 mg) are likely to be as much as 1000 times greater than the amounts that could be obtained from the diet.112 This is a narrative overview of the topic of MetS. A systematic review was not performed; therefore, there may be relevant information missing from this review. The contents of this overview focuses on the opinions of the authors, and therefore, others may disagree with our opinions or approaches to management. This overview is limited by the studies that have been published. To date, no studies have been published that identify the effectiveness of a combination of a dietary intervention, such as the Spanish

This is a narrative overview of the topic of MetS. A systematic review was not performed; therefore, there may be relevant information missing from this review. The contents of this overview focuses on the opinions of the authors, and therefore, others may disagree with our opinions or approaches to management. This overview is limited by the studies that have been published. To date, no studies have been published that identify the effectiveness of a combination of a dietary intervention, such as the Spanish

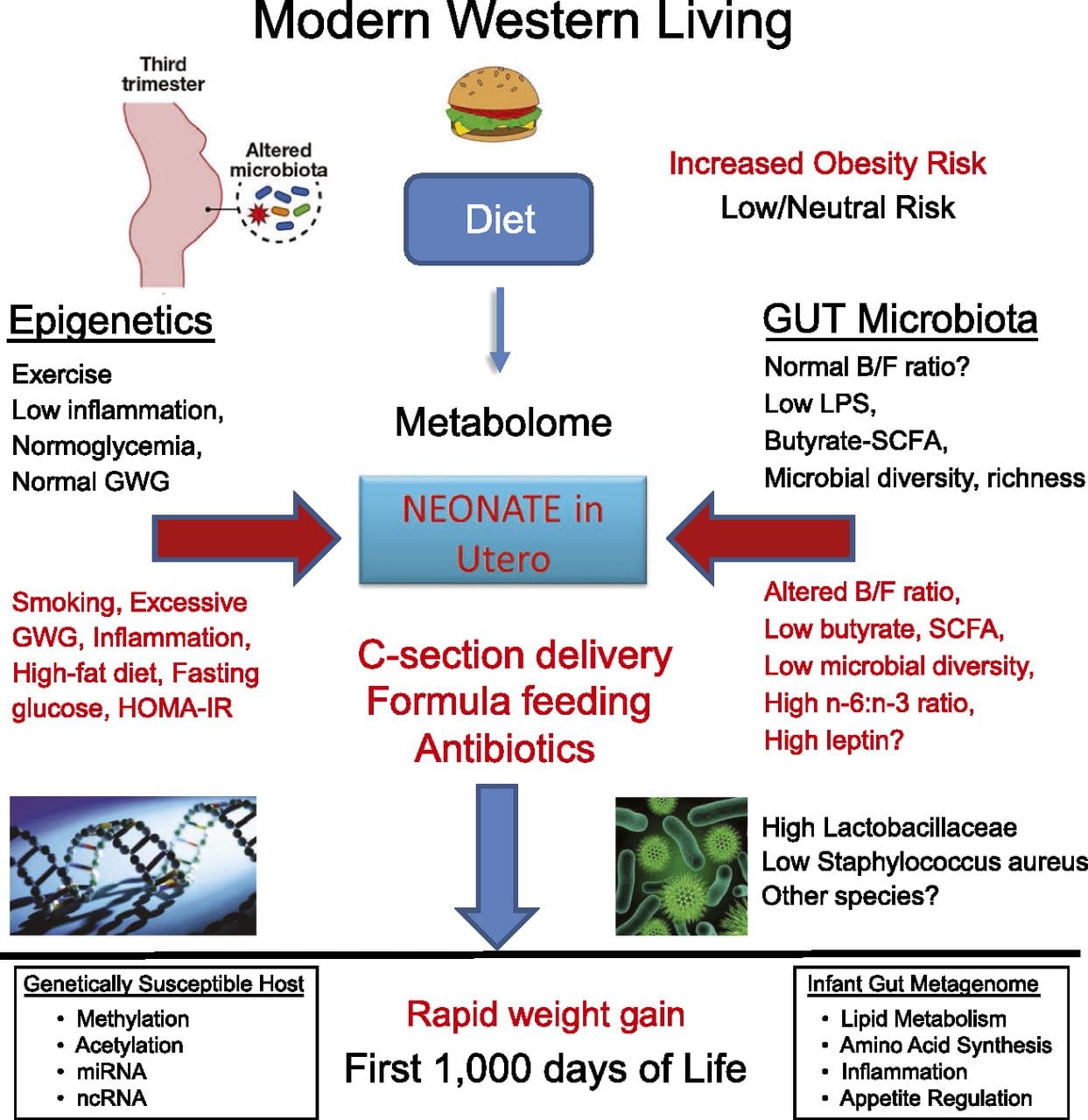

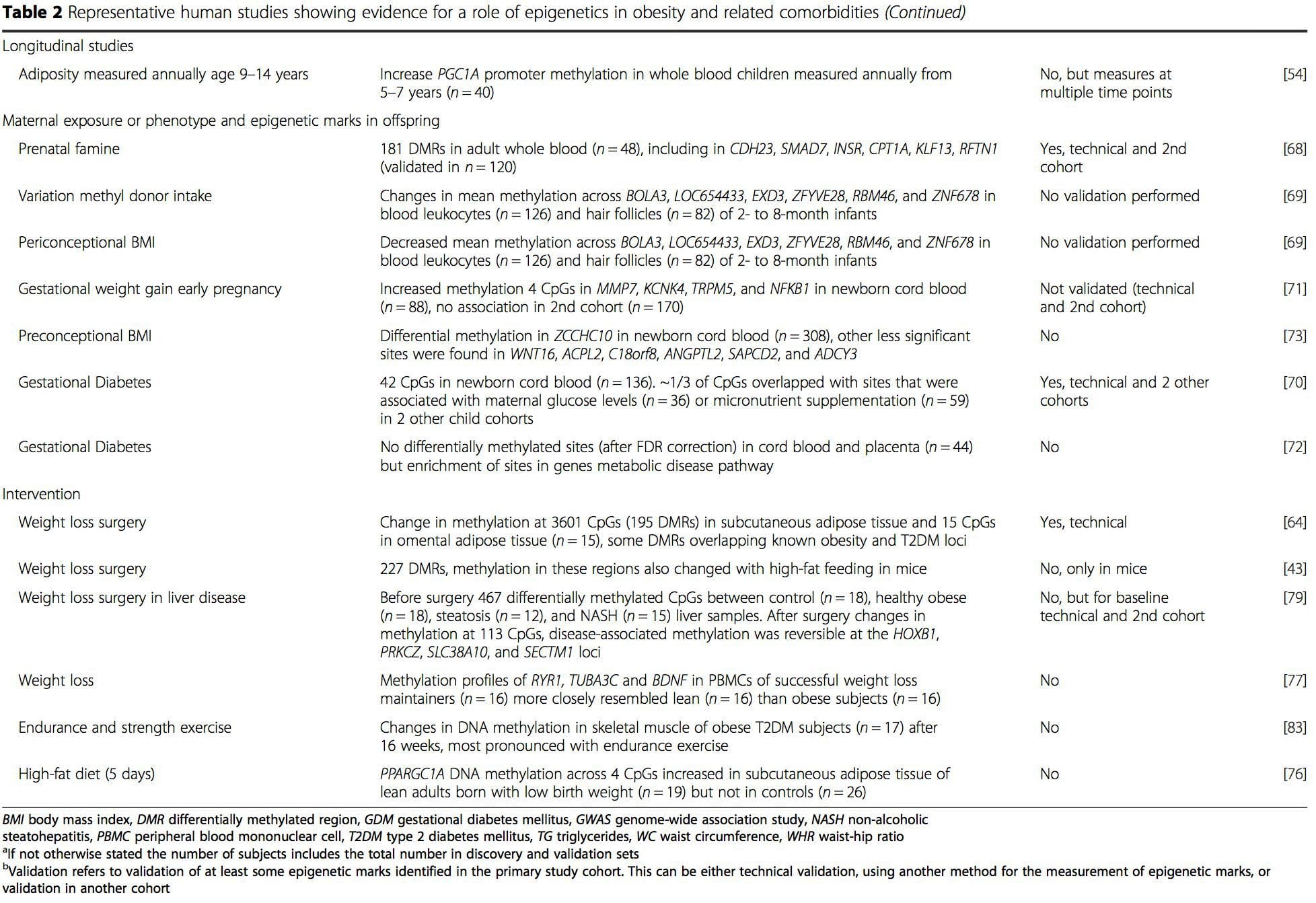

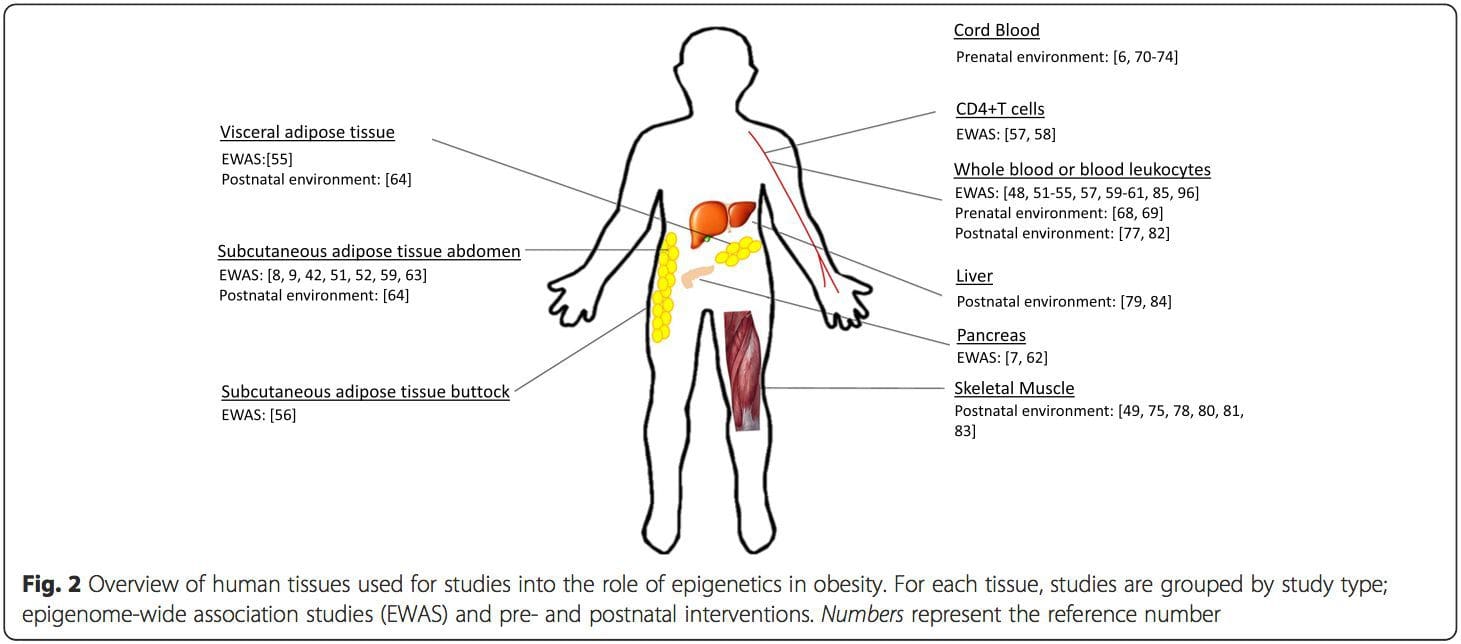

Obesity is a complex, multifactorial disease, and better understanding of the mechanisms underlying the interactions between lifestyle, environment, and genetics is critical for developing effective strategies for prevention and treatment [1].

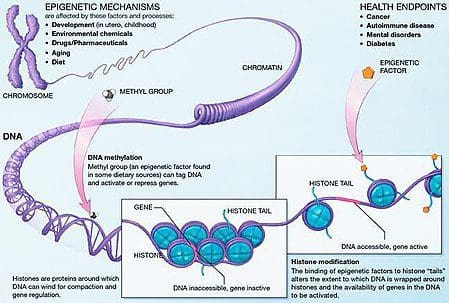

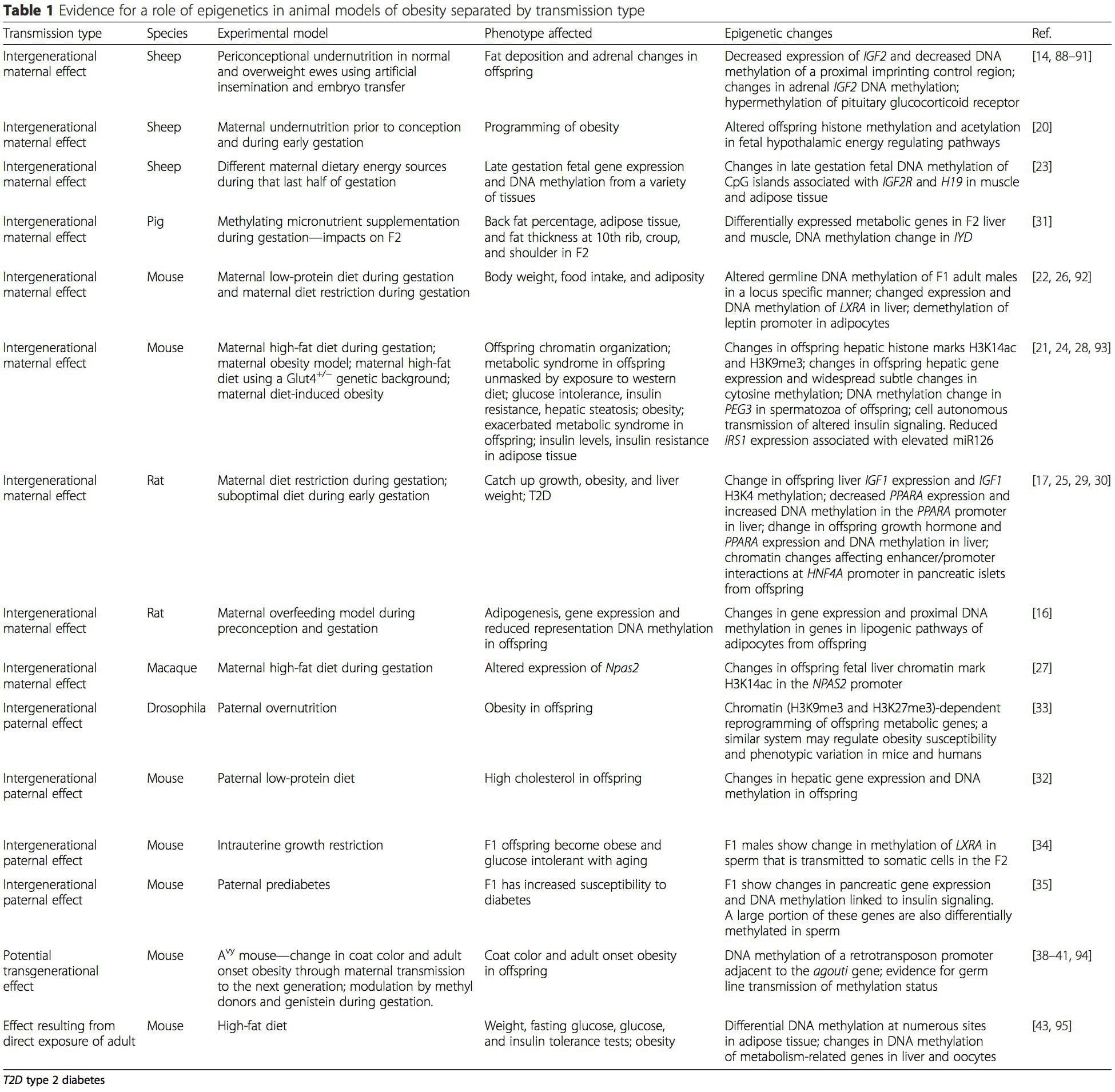

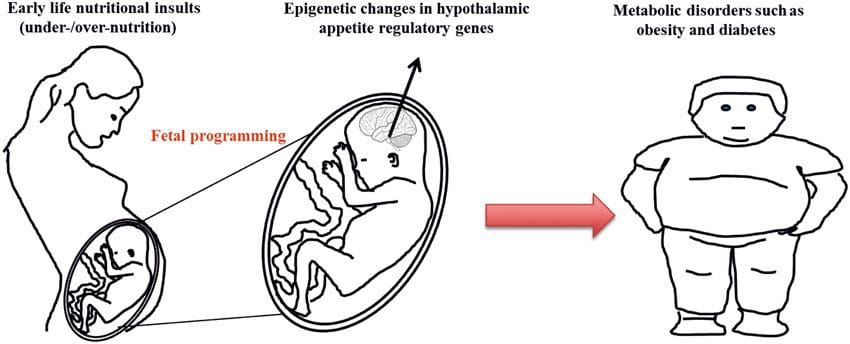

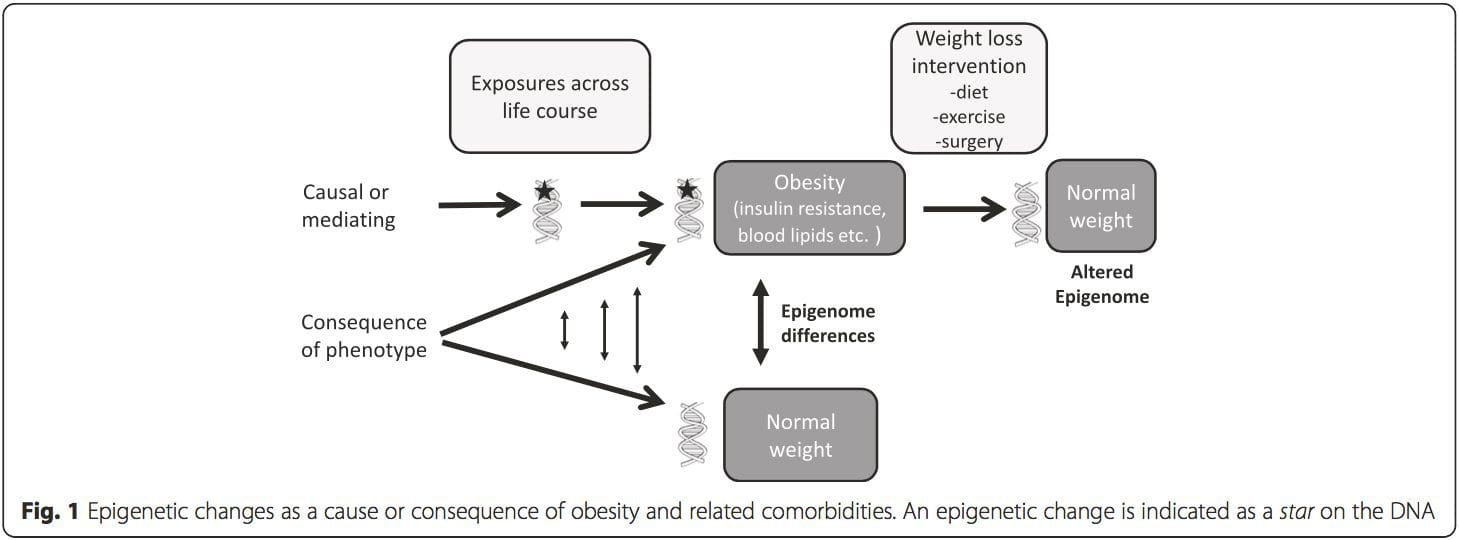

Obesity is a complex, multifactorial disease, and better understanding of the mechanisms underlying the interactions between lifestyle, environment, and genetics is critical for developing effective strategies for prevention and treatment [1]. Animal models provide unique opportunities for highly controlled studies that provide mechanistic insight into�the role of specific epigenetic marks, both as indicators of current metabolic status and as predictors of the future risk of obesity and metabolic disease. A particularly important aspect of animal studies is that they allow for the assessment of epigenetic changes within target tissues, including the liver and hypothalamus, which is much more difficult in humans. Moreover, the ability to harvest large quantities of fresh tissue makes it possible to assess multiple chromatin marks as well as DNA methylation. Some of these epigenetic modifications either alone or in combination may be responsive to environmental programming. In animal models, it is also possible to study multiple generations of offspring and thus enable differentiation between trans-generational and intergenerational transmission of obesity risk mediated by epigenetic memory of parental nutritional status, which cannot be easily distinguished in human studies. We use the former term for meiotic transmission of risk in the absence of continued exposure while the latter primarily entails direct transmission of risk through metabolic reprogramming of the fetus or gametes.

Animal models provide unique opportunities for highly controlled studies that provide mechanistic insight into�the role of specific epigenetic marks, both as indicators of current metabolic status and as predictors of the future risk of obesity and metabolic disease. A particularly important aspect of animal studies is that they allow for the assessment of epigenetic changes within target tissues, including the liver and hypothalamus, which is much more difficult in humans. Moreover, the ability to harvest large quantities of fresh tissue makes it possible to assess multiple chromatin marks as well as DNA methylation. Some of these epigenetic modifications either alone or in combination may be responsive to environmental programming. In animal models, it is also possible to study multiple generations of offspring and thus enable differentiation between trans-generational and intergenerational transmission of obesity risk mediated by epigenetic memory of parental nutritional status, which cannot be easily distinguished in human studies. We use the former term for meiotic transmission of risk in the absence of continued exposure while the latter primarily entails direct transmission of risk through metabolic reprogramming of the fetus or gametes. (i) Epigenetic Changes In Offspring Associated With Maternal Nutrition During Gestation

(i) Epigenetic Changes In Offspring Associated With Maternal Nutrition During Gestation Maternal nutritional supplementation, undernutrition, and over nutrition during pregnancy can alter fat deposition and energy homeostasis in offspring [11, 13�15, 19]. Associated with these effects in the offspring are changes in DNA methylation, histone post-translational modifications, and gene expression for several target genes,�especially genes regulating fatty acid metabolism and insulin signaling [16, 17, 20�30]. The diversity of animal models used in these studies and the common metabolic pathways impacted suggest an evolutionarily conserved adaptive response mediated by epigenetic modification. However, few of the specific identified genes and epigenetic changes have been cross-validated in related studies, and large-scale genome-wide investigations have typically not been applied. A major hindrance to comparison of these studies is the different develop mental windows subjected to nutritional challenge, which may cause considerably different outcomes. Proof that the epigenetic changes are causal rather than being associated with offspring phenotypic changes is also required. This will necessitate the identification of a parental nutritionally induced epigenetic �memory� response that precedes development of the altered phenotype in offspring.