by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Basal Metabolic Index (BMI), Fitness, Metabolic Syndrome, Power & Strength, PUSH-as-Rx

Personal Training 101

How You Get Energy & How You Use It

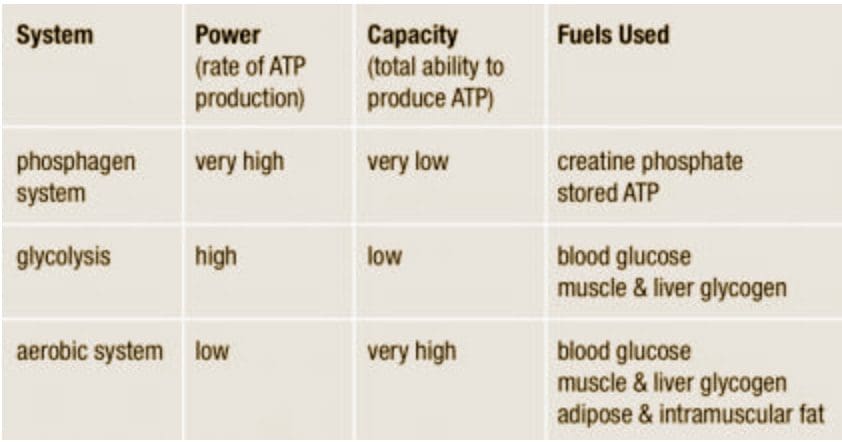

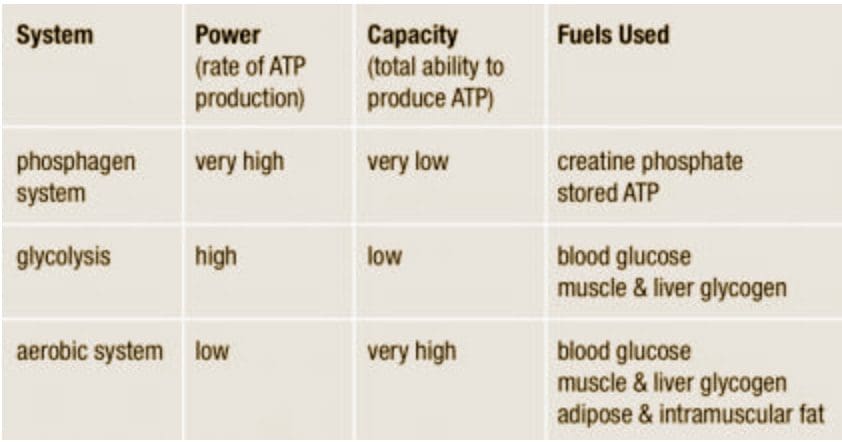

We usually talk of energy in general terms, as in �I don�t have a lot of energy today� or �You can feel the energy in the room.� But what really is energy? Where do we get the energy to move? How do we use it? How do we get more of it? Ultimately, what controls our movements? The three metabolic energy pathways are the�phosphagen system, glycolysis�and the�aerobic system.�How do they work, and what is their effect?

We usually talk of energy in general terms, as in �I don�t have a lot of energy today� or �You can feel the energy in the room.� But what really is energy? Where do we get the energy to move? How do we use it? How do we get more of it? Ultimately, what controls our movements? The three metabolic energy pathways are the�phosphagen system, glycolysis�and the�aerobic system.�How do they work, and what is their effect?

Albert Einstein, in his infinite wisdom, discovered that the total energy of an object is equal to the mass of the object multiplied by the square of the speed of light. His formula for atomic energy, E = mc2, has become the most recognized mathematical formula in the world. According to his equation, any change in the energy of an object causes a change in the mass of that object. The change in energy can come in many forms, including mechanical, thermal, electromagnetic, chemical, electrical or nuclear. Energy is all around us. The lights in your home, a microwave, a telephone, the sun; all transmit energy. Even though the solar energy that heats the earth is quite different from the energy used to run up a hill, energy, as the first law of thermodynamics tells us, can be neither created nor destroyed. It is simply changed from one form to another.

ATP Re-Synthesis

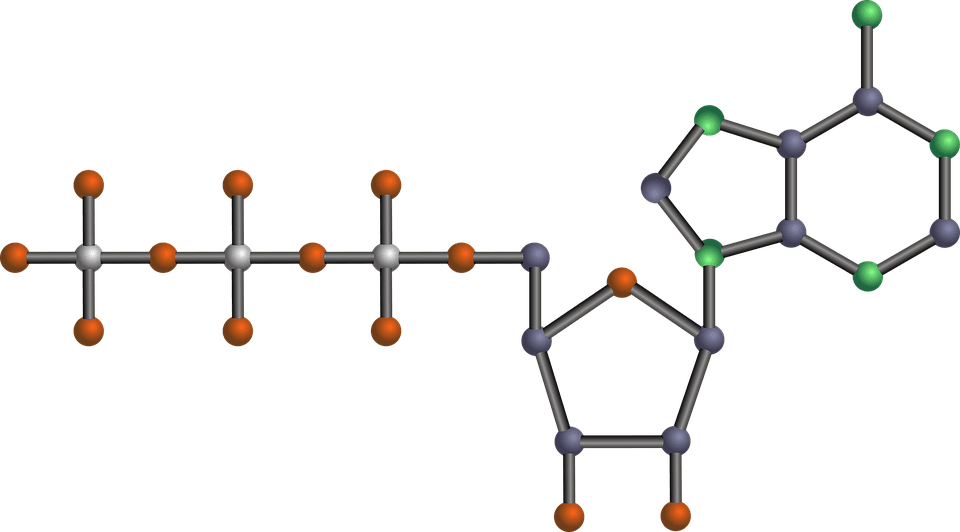

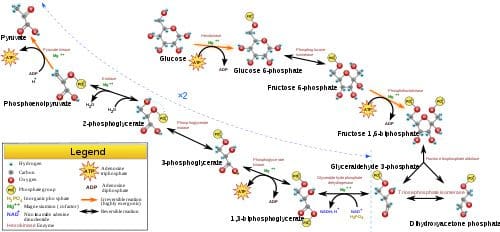

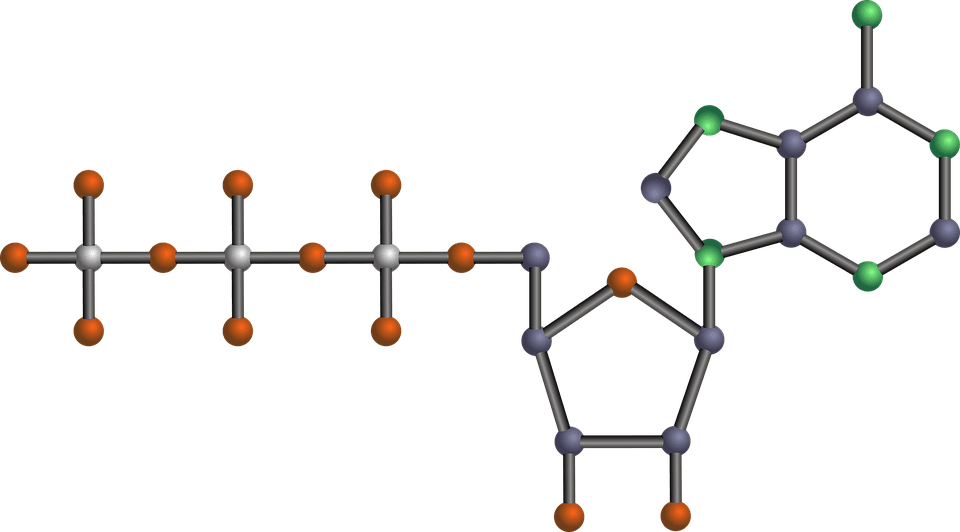

The energy for all physical activity comes from the conversion of high-energy phosphates (adenosine�triphosphate�ATP) to lower-energy phosphates (adenosine�diphosphate�ADP; adenosine�monophosphate�AMP; and inorganic phosphate, Pi). During this breakdown (hydrolysis) of ATP, which is a water-requiring process, a proton, energy and heat are produced: ATP + H2O ���ADP + Pi�+ H+�+ energy + heat. Since our muscles don�t store much ATP, we must constantly resynthesize it. The hydrolysis and resynthesis of ATP is thus a circular process�ATP is hydrolyzed into ADP and Pi, and then ADP and Pi�combine to resynthesize ATP. Alternatively, two ADP molecules can combine to produce ATP and AMP: ADP + ADP ���ATP + AMP.

The energy for all physical activity comes from the conversion of high-energy phosphates (adenosine�triphosphate�ATP) to lower-energy phosphates (adenosine�diphosphate�ADP; adenosine�monophosphate�AMP; and inorganic phosphate, Pi). During this breakdown (hydrolysis) of ATP, which is a water-requiring process, a proton, energy and heat are produced: ATP + H2O ���ADP + Pi�+ H+�+ energy + heat. Since our muscles don�t store much ATP, we must constantly resynthesize it. The hydrolysis and resynthesis of ATP is thus a circular process�ATP is hydrolyzed into ADP and Pi, and then ADP and Pi�combine to resynthesize ATP. Alternatively, two ADP molecules can combine to produce ATP and AMP: ADP + ADP ���ATP + AMP.

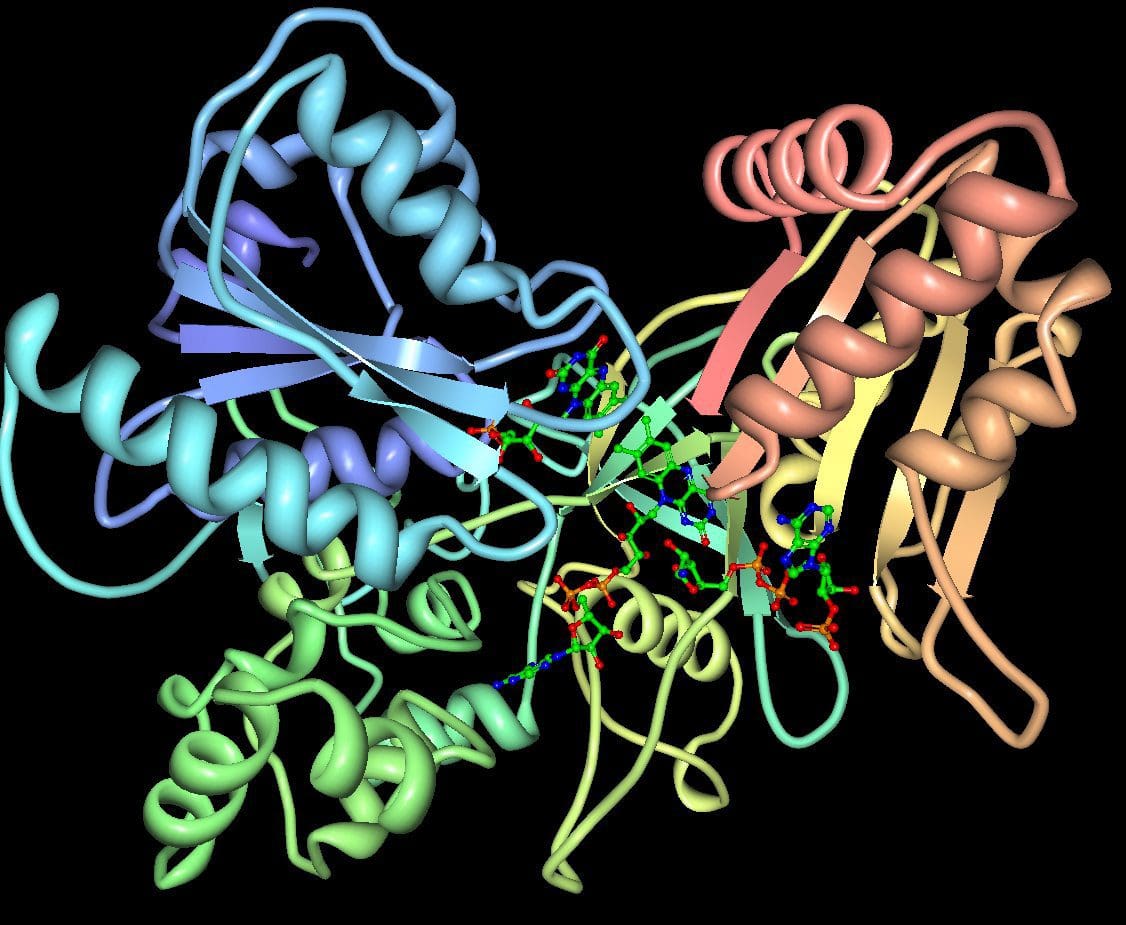

Like many other animals, humans produce ATP through three metabolic pathways that consist of many enzyme-catalyzed chemical reactions: the phosphagen system, glycolysis and the aerobic system. Which pathway your clients use for the primary production of ATP depends on how quickly they need it and how much of it they need. Lifting heavy weights, for instance, requires energy much more quickly than jogging on the treadmill, necessitating the reliance on different energy systems. However, the production of ATP is never achieved by the exclusive use of one energy system, but rather by the coordinated response of all energy systems contributing to different degrees.

1. Phosphagen System

During short-term, intense activities, a large amount of power needs to be produced by the muscles, creating a high demand for ATP. The phosphagen system (also called the ATP-CP system) is the quickest way to resynthesize ATP (Robergs & Roberts 1997). Creatine phosphate (CP), which is stored in skeletal muscles, donates a phosphate to ADP to produce ATP: ADP + CP ���ATP + C. No carbohydrate or fat is used in this process; the regeneration of ATP comes solely from stored CP. Since this process does not need oxygen to resynthesize ATP, it is anaerobic, or oxygen-independent. As the fastest way to resynthesize ATP, the phosphagen system is the predominant energy system used for all-out exercise lasting up to about 10 seconds. However, since there is a limited amount of stored CP and ATP in skeletal muscles, fatigue occurs rapidly.

During short-term, intense activities, a large amount of power needs to be produced by the muscles, creating a high demand for ATP. The phosphagen system (also called the ATP-CP system) is the quickest way to resynthesize ATP (Robergs & Roberts 1997). Creatine phosphate (CP), which is stored in skeletal muscles, donates a phosphate to ADP to produce ATP: ADP + CP ���ATP + C. No carbohydrate or fat is used in this process; the regeneration of ATP comes solely from stored CP. Since this process does not need oxygen to resynthesize ATP, it is anaerobic, or oxygen-independent. As the fastest way to resynthesize ATP, the phosphagen system is the predominant energy system used for all-out exercise lasting up to about 10 seconds. However, since there is a limited amount of stored CP and ATP in skeletal muscles, fatigue occurs rapidly.

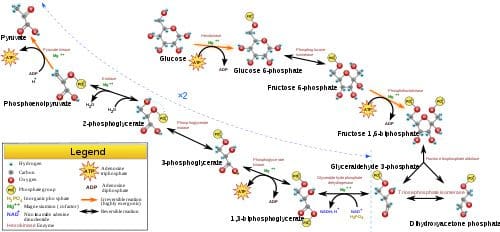

2. Glycolysis

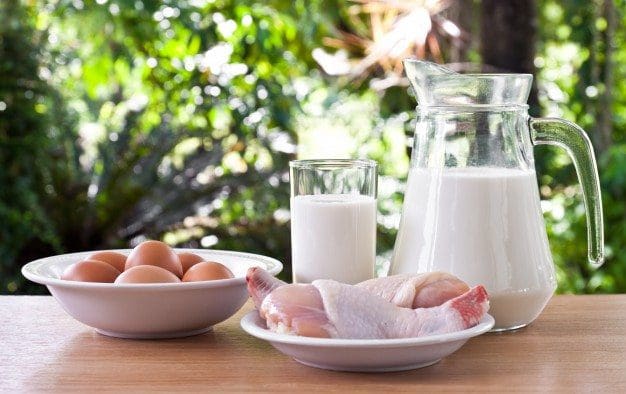

Glycolysis is the predominant energy system used for all-out exercise lasting from 30 seconds to about 2 minutes and is the second-fastest way to resynthesize ATP. During glycolysis, carbohydrate�in the form of either blood glucose (sugar) or muscle glycogen (the stored form of glucose)�is broken down through a series of chemical reactions to form pyruvate (glycogen is first broken down into glucose through a process called�glycogenolysis). For every molecule of glucose broken down to pyruvate through glycolysis, two molecules of usable ATP are produced (Brooks et al. 2000). Thus, very little energy is produced through this pathway, but the trade-off is that you get the energy quickly. Once pyruvate is formed, it has two fates: conversion to lactate or conversion to a metabolic intermediary molecule called acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA), which enters the mitochondria for oxidation and the production of more ATP (Robergs & Roberts 1997). Conversion to lactate occurs when the demand for oxygen is greater than the supply (i.e., during anaerobic exercise). Conversely, when there is enough oxygen available to meet the muscles� needs (i.e., during aerobic exercise), pyruvate (via acetyl-CoA) enters the mitochondria and goes through aerobic metabolism.

Glycolysis is the predominant energy system used for all-out exercise lasting from 30 seconds to about 2 minutes and is the second-fastest way to resynthesize ATP. During glycolysis, carbohydrate�in the form of either blood glucose (sugar) or muscle glycogen (the stored form of glucose)�is broken down through a series of chemical reactions to form pyruvate (glycogen is first broken down into glucose through a process called�glycogenolysis). For every molecule of glucose broken down to pyruvate through glycolysis, two molecules of usable ATP are produced (Brooks et al. 2000). Thus, very little energy is produced through this pathway, but the trade-off is that you get the energy quickly. Once pyruvate is formed, it has two fates: conversion to lactate or conversion to a metabolic intermediary molecule called acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA), which enters the mitochondria for oxidation and the production of more ATP (Robergs & Roberts 1997). Conversion to lactate occurs when the demand for oxygen is greater than the supply (i.e., during anaerobic exercise). Conversely, when there is enough oxygen available to meet the muscles� needs (i.e., during aerobic exercise), pyruvate (via acetyl-CoA) enters the mitochondria and goes through aerobic metabolism.

When oxygen is not supplied fast enough to meet the muscles� needs (anaerobic glycolysis), there is an increase in hydrogen ions (which causes the muscle pH to decrease; a condition called acidosis) and other metabolites (ADP, Pi�and potassium ions). Acidosis and the accumulation of these other metabolites cause a number of problems inside the muscles, including inhibition of specific enzymes involved in metabolism and muscle contraction, inhibition of the release of calcium (the trigger for muscle contraction) from its storage site in muscles, and interference with the muscles� electrical charges (Enoka & Stuart 1992; Glaister 2005; McLester 1997). As a result of these changes, muscles lose their ability to contract effectively, and muscle force production and exercise intensity ultimately decrease.

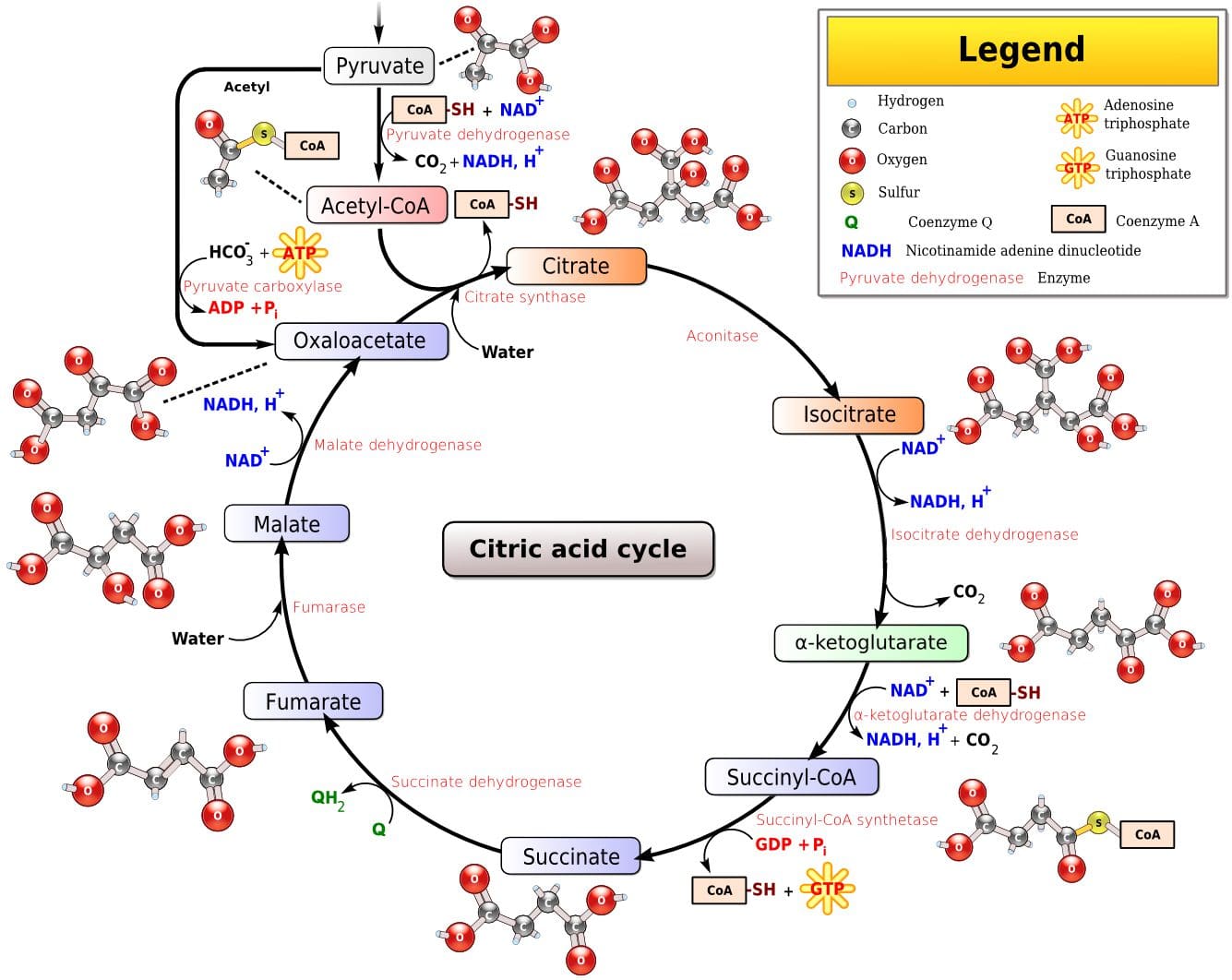

3. Aerobic System

Since humans evolved for aerobic activities (Hochachka, Gunga & Kirsch 1998; Hochachka & Monge 2000), it�s not surprising that the aerobic system, which is dependent on oxygen, is the most complex of the three energy systems. The metabolic reactions that take place in the presence of oxygen are responsible for most of the cellular energy produced by the body. However, aerobic metabolism is the slowest way to resynthesize ATP. Oxygen, as the patriarch of metabolism, knows that it is worth the wait, as it controls the fate of endurance and is the sustenance of life. �I�m oxygen,� it says to the muscle, with more than a hint of superiority. �I can give you a lot of ATP, but you will have to wait for it.�

Since humans evolved for aerobic activities (Hochachka, Gunga & Kirsch 1998; Hochachka & Monge 2000), it�s not surprising that the aerobic system, which is dependent on oxygen, is the most complex of the three energy systems. The metabolic reactions that take place in the presence of oxygen are responsible for most of the cellular energy produced by the body. However, aerobic metabolism is the slowest way to resynthesize ATP. Oxygen, as the patriarch of metabolism, knows that it is worth the wait, as it controls the fate of endurance and is the sustenance of life. �I�m oxygen,� it says to the muscle, with more than a hint of superiority. �I can give you a lot of ATP, but you will have to wait for it.�

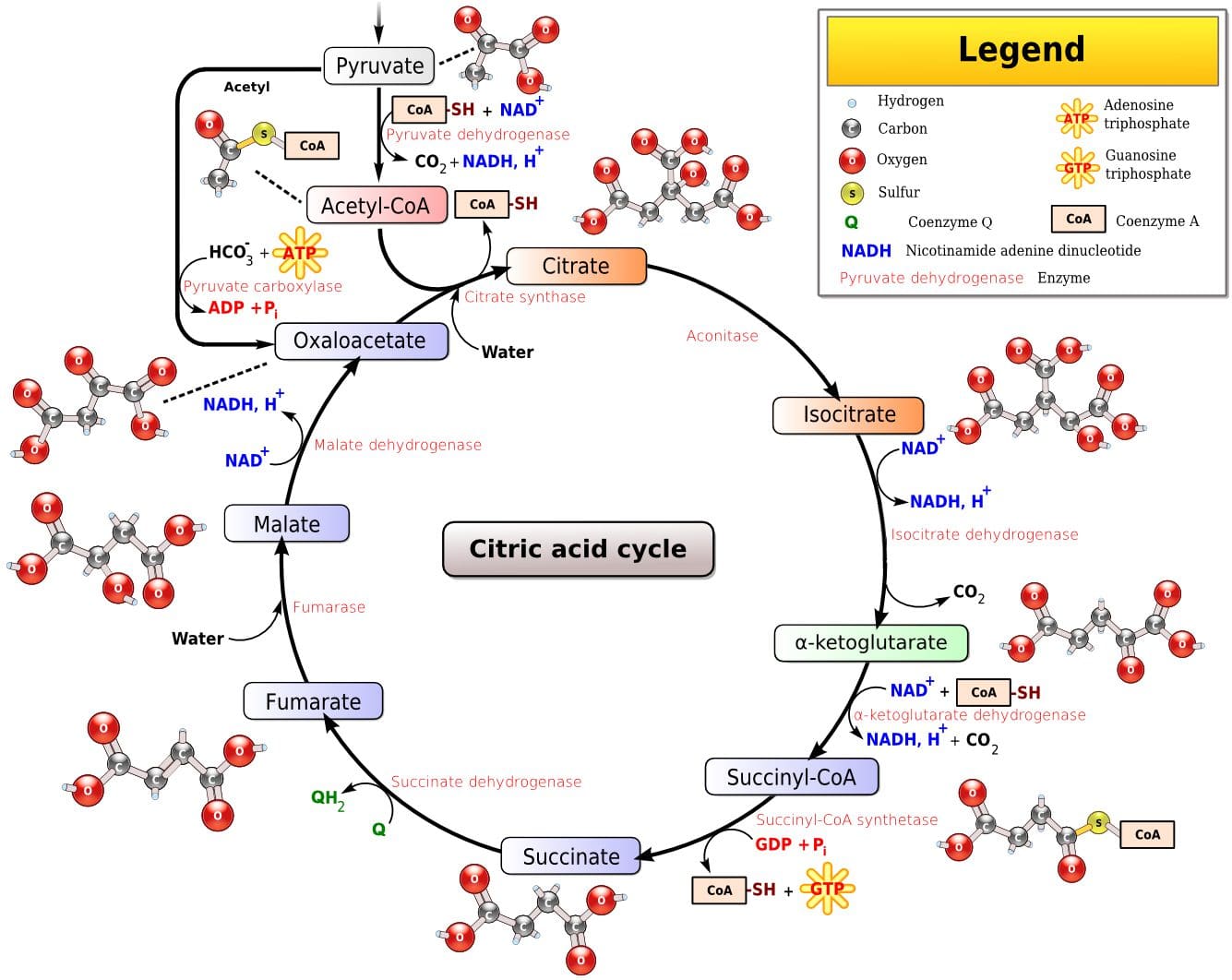

The aerobic system�which includes the�Krebs cycle�(also called the�citric acid cycle or TCA cycle) and the�electron transport chain�uses blood glucose, glycogen and fat as fuels to resynthesize ATP in the mitochondria of muscle cells (see the sidebar �Energy System Characteristics�). Given its location, the aerobic system is also called�mitochondrial respiration.�When using carbohydrate, glucose and glycogen are first metabolized through glycolysis, with the resulting pyruvate used to form acetyl-CoA, which enters the Krebs cycle. The electrons produced in the Krebs cycle are then transported through the electron transport chain, where ATP and water are produced (a process called�oxidative phosphorylation) (Robergs & Roberts 1997). Complete oxidation of glucose via glycolysis, the Krebs cycle and the electron transport chain produces 36 molecules of ATP for every molecule of glucose broken down (Robergs & Roberts 1997). Thus, the aerobic system produces 18 times more ATP than does anaerobic glycolysis from each glucose molecule.

Fat, which is stored as triglyceride in adipose tissue underneath the skin and within skeletal muscles (called�intramuscular triglyceride), is the other major fuel for the aerobic system, and is the largest store of energy in the body. When using fat, triglycerides are first broken down into free fatty acids and glycerol (a process called�lipolysis). The free fatty acids, which are composed of a long chain of carbon atoms, are transported to the muscle mitochondria, where the carbon atoms are used to produce acetyl-CoA (a process called�beta-oxidation).

Fat, which is stored as triglyceride in adipose tissue underneath the skin and within skeletal muscles (called�intramuscular triglyceride), is the other major fuel for the aerobic system, and is the largest store of energy in the body. When using fat, triglycerides are first broken down into free fatty acids and glycerol (a process called�lipolysis). The free fatty acids, which are composed of a long chain of carbon atoms, are transported to the muscle mitochondria, where the carbon atoms are used to produce acetyl-CoA (a process called�beta-oxidation).

Following acetyl-CoA formation, fat metabolism is identical to carbohydrate metabolism, with acetyl-CoA entering the Krebs cycle and the electrons being transported to the electron transport chain to form ATP and water. The oxidation of free fatty acids yields many more ATP molecules than the oxidation of glucose or glycogen. For example, the oxidation of the fatty acid palmitate produces 129 molecules of ATP (Brooks et al. 2000). No wonder clients can sustain an aerobic activity longer than an anaerobic one!

Understanding how energy is produced for physical activity is important when it comes to programming exercise at the proper intensity and duration for your clients. So the next time your clients get done with a workout and think, �I have a lot of energy,� you�ll know exactly where they got it.

Energy System Characteristics

Have clients warm up and cool down before and after each workout.

Phosphagen System

An effective workout for this system is short, very fast sprints on the treadmill or bike lasting 5�15 seconds with 3�5 minutes of rest between each. The long rest periods allow for complete replenishment of creatine phosphate in the muscles so it can be reused for the next interval.

- 2 sets of 8 x 5 seconds at close to top speed with 3:00 passive rest and 5:00 rest between sets

- 5 x 10 seconds at close to top speed with 3:00�4:00 passive rest

Glycolysis

This system can be trained using fast intervals lasting 30 seconds to 2 minutes with an active-recovery period twice as long as the work period (1:2 work-to-rest ratio).

- 8�10 x 30 seconds fast with 1:00 active recovery

- 4 x 1:30 fast with 3:00 active recovery

Aerobic System

While the phosphagen system and glycolysis are best trained with intervals, because those metabolic systems are emphasized only during high-intensity activities, the aerobic system can be trained with both continuous exercise and intervals.

- 60 minutes at 70%�75% maximum heart rate

- 15- to 20-minute tempo workout at lactate threshold intensity (about 80%�85% maximum heart rate)

- 5 x 3:00 at 95%�100% maximum heart rate with 3:00 active recovery

by�Jason Karp, PhD

References:

Brooks, G.A., et al. 2000.�Exercise Physiology: Human Bioenergetics and Its Applications.Mountain View, CA: Mayfield.

Enoka, R.M., & Stuart, D.G. 1992. Neurobiology of muscle fatigue.�Journal of Applied Physiology, 72�(5), 1631�48.

Glaister, M. 2005. Multiple sprint work: Physiological responses, mechanisms of fatigue and the influence of aerobic fitness.�Sports Medicine, 35�(9), 757�77.

Hochachka, P.W., Gunga, H.C., & Kirsch, K. 1998. Our ancestral physiological phenotype: An adaptation for hypoxia tolerance and for endurance performance?�Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 95,�1915�20.

Hochachka, P.W., & Monge, C. 2000. Evolution of human hypoxia tolerance physiology.�Advances in Experimental and Medical Biology, 475,�25�43.

McLester, J.R. 1997. Muscle contraction and fatigue: The role of adenosine 5′-diphosphate and inorganic phosphate.�Sports Medicine, 23�(5), 287�305.

Robergs, R.A. & Roberts, S.O. 1997.�Exercise Physiology: Exercise, Performance, and Clinical Applications.�Boston: William C. Brown.

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Functional Medicine, PUSH-as-Rx, Wellness

Functional Medicine: Glossary

Allostasis: The process of achieving stability, or homeostasis, through physiological or behavioral change. This can be carried out by means of alteration in HPATG axis hormones, the autonomic nervous system, cytokines, or a number of other systems, and is generally adaptive in the short term. It is essential in order to maintain internal viability amid changing conditions.

Allostasis: The process of achieving stability, or homeostasis, through physiological or behavioral change. This can be carried out by means of alteration in HPATG axis hormones, the autonomic nervous system, cytokines, or a number of other systems, and is generally adaptive in the short term. It is essential in order to maintain internal viability amid changing conditions.

Antecedents: Factors that predispose to acute or chronic illness. For a person who is ill, antecedents form the illness diathesis. From the perspective of prevention, they are risk factors. Examples of genetic antecedents include the breast cancer risk genes BRCA1 and BRCA2.

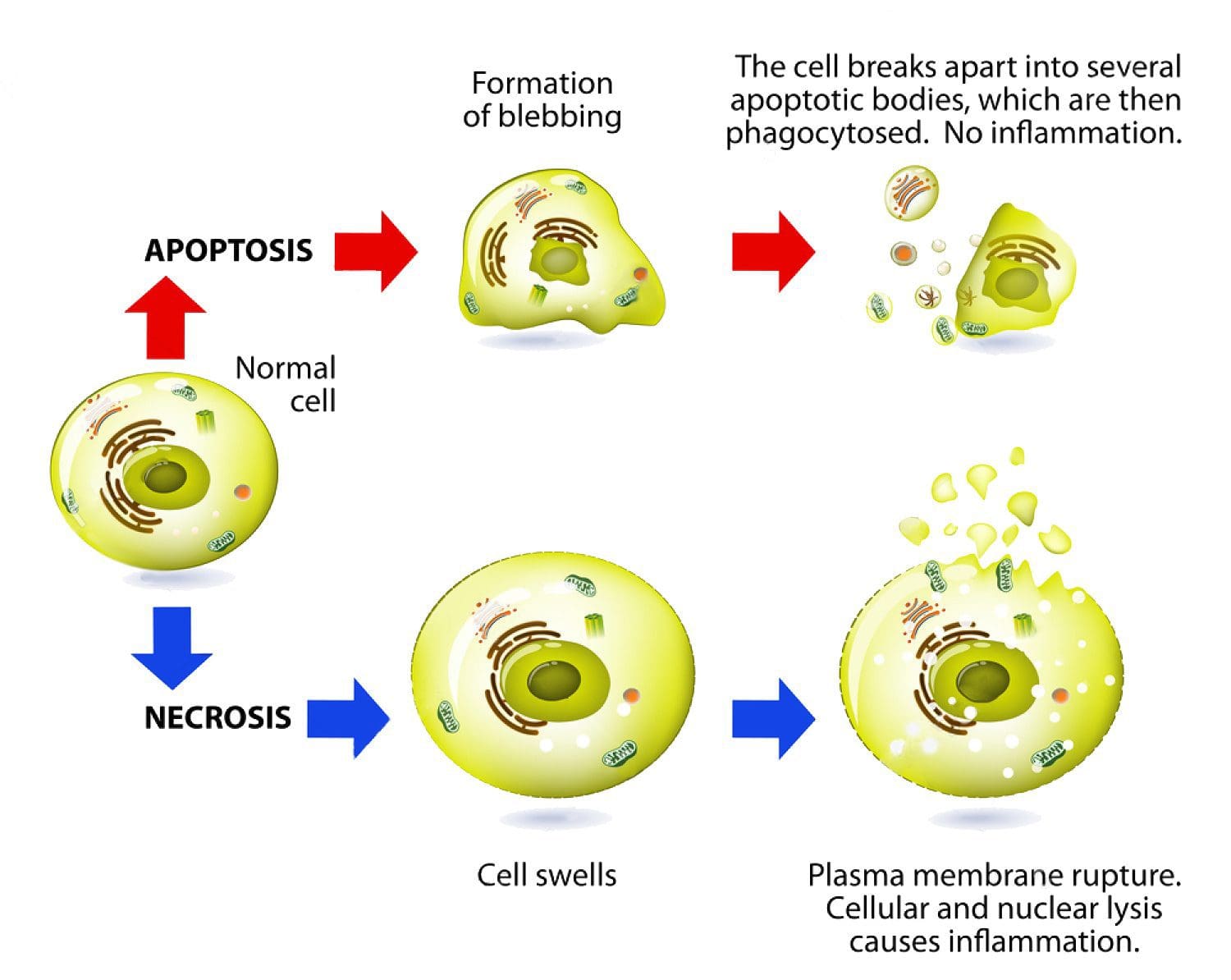

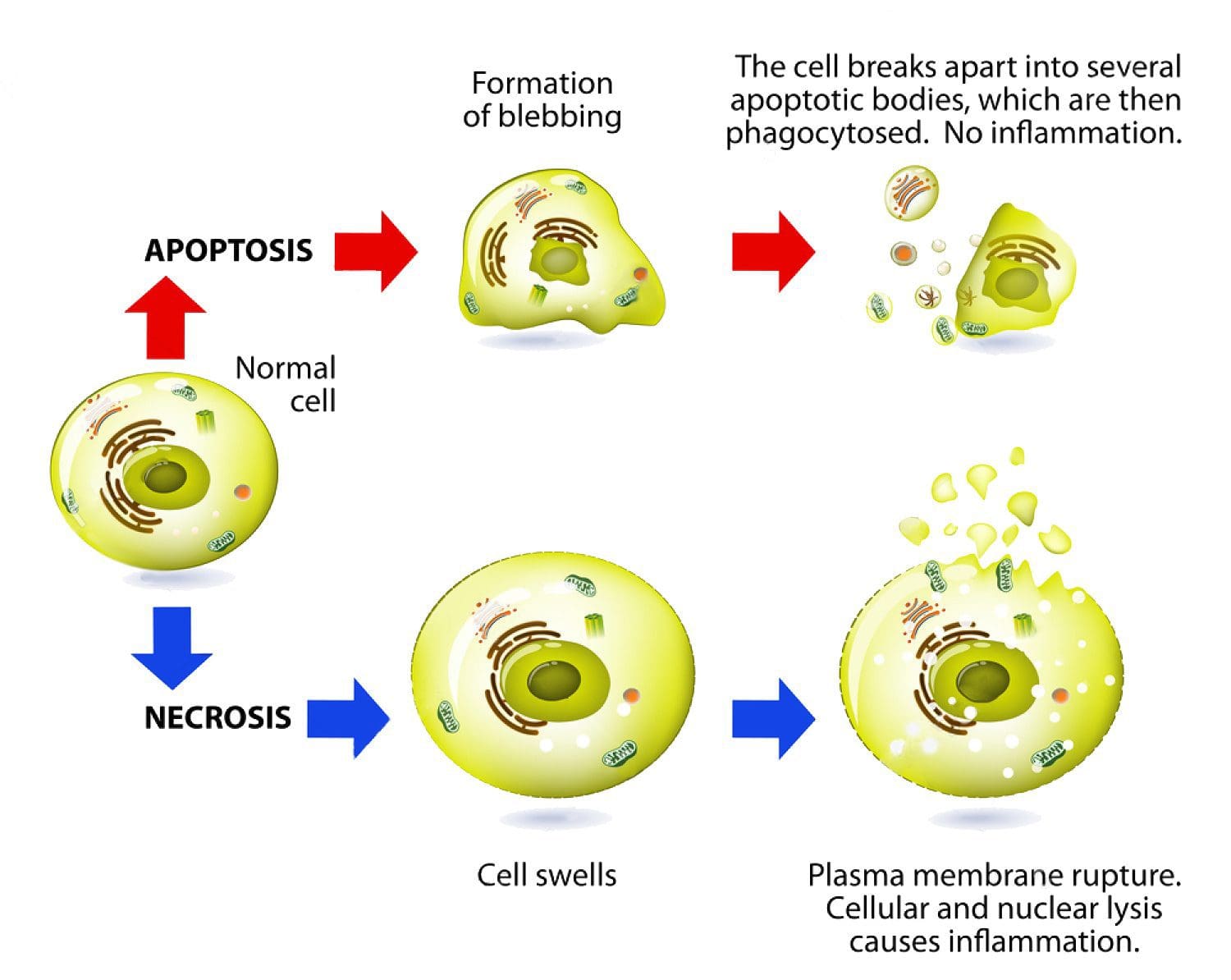

Apoptosis: Programmed cell death. As a normal part of growth and development, cells that are superfluous or that become damaged activate a cascade of intracellular processes leading to their own demise. In cancer cells, DNA damage may inactivate the apoptosis cascade, allowing mutated cells to survive and proliferate.

Biochemical individuality: Each individual has a unique physiological and biochemical composition, based upon the interactions of his or her individual genetic make-up with lifestyle and environment�i.e., the continuous exposure to inputs (diet, experiences, nutrients, beliefs, activity, toxins, medications, etc.) that influence our genes. It is this combination of factors that accounts for the endless variety of phenotypic responses seen every day by clinicians. The unique makeup of each individual requires personalized levels of nutrition and a lifestyle adapted to that individual�s needs in order to achieve optimal health. The consequences of not meeting the specific needs of the individual are expressed, over time, as degenerative disease.�

Bioidentical Hormone Therapy: Giving exogenous hormones that are identical in structure to the endogenous hormones.�

Biomarker: A substance used as an indicator of a biological state. Such characteristics are objectively measured and evaluated as indicators of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or pharmacologic responses to a therapeutic intervention. Cancer biomarkers include prostate specific antigen (PSA) and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA).

Biotransformation: The chemical modification(s) of a compound made by an organism. Compounds modified in the body include, but are not limited to, nutrients, amino acids, toxins, heavy metals, and drugs. Biotransformation also renders nonpolar compounds polar so that they are excreted, not reabsorbed in renal tubules.

Cancer: A group of diseases characterized by uncontrolled growth and spread of abnormal cells, which, if not controlled, can result in death. Cancer is caused by both external factors (tobacco, infectious organisms, chemicals, and radiation) and internal factors (inherited mutations, hormones, immune conditions, and mutations that occur from metabolism), two or more of which may act together or in sequence to initiate or promote carcinogenesis. Ten or more years often pass between exposure to external factors and detectable cancer.

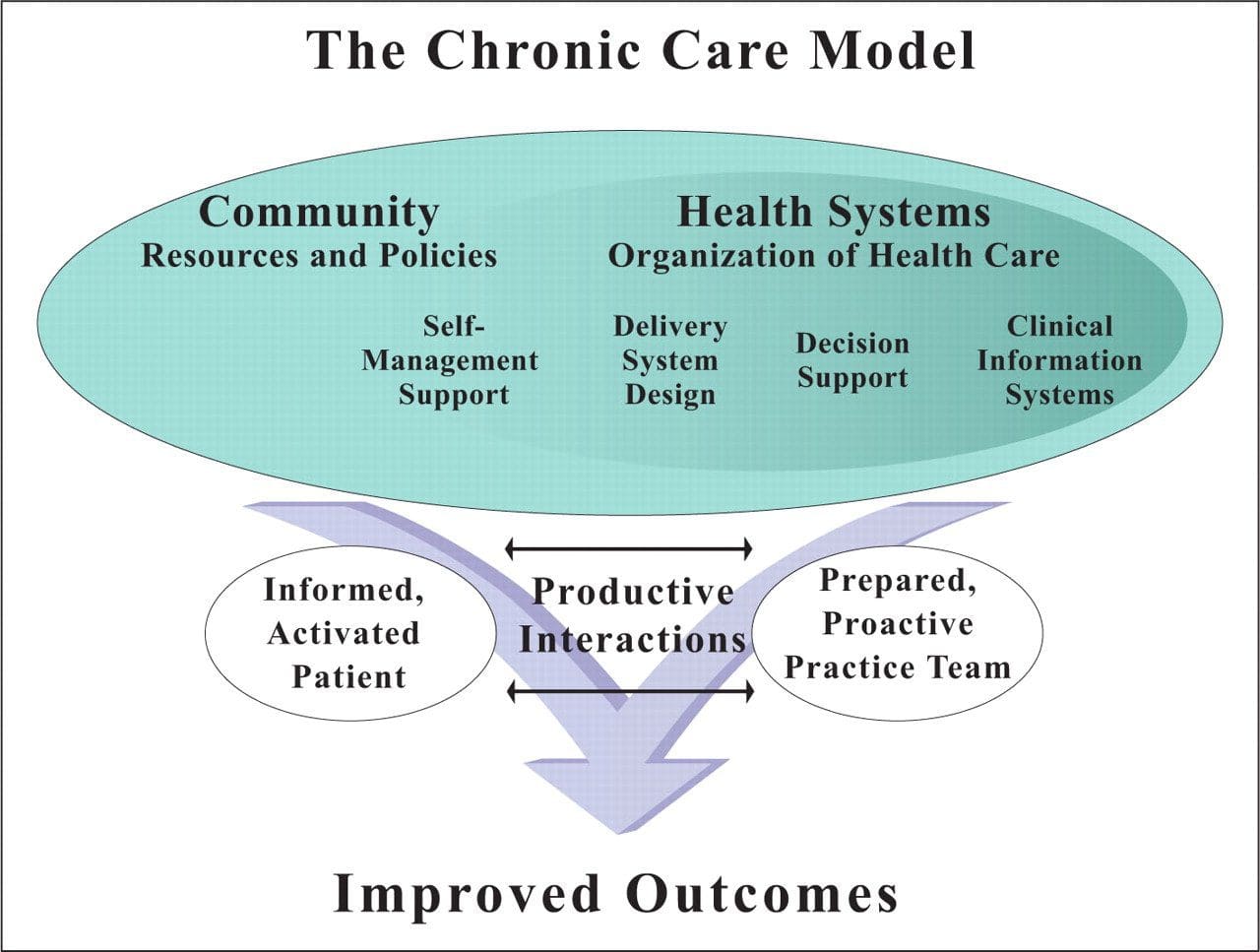

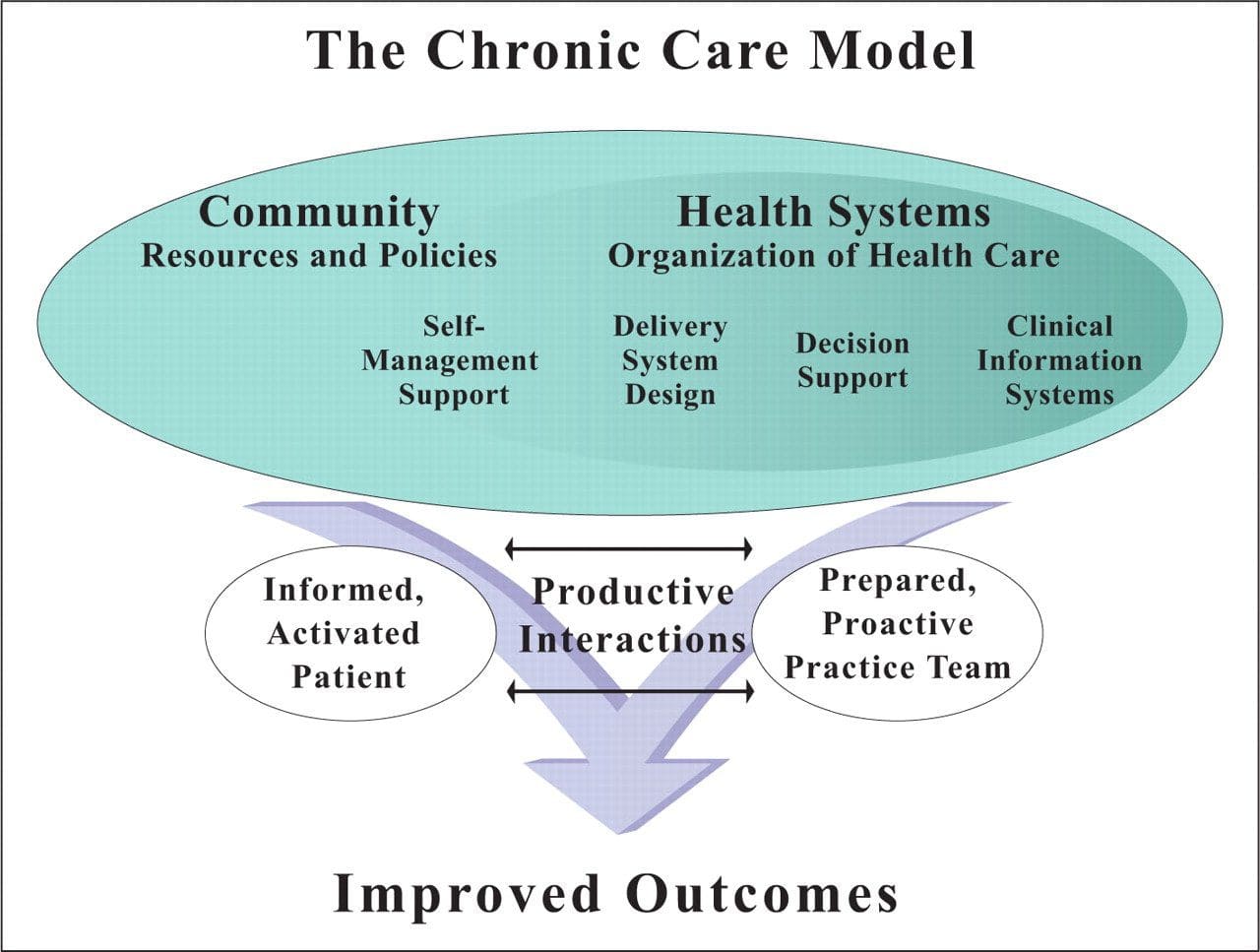

Chronic Care Model: Developed by Wagner and colleagues, the primary focus of this model is to include the essential elements of a healthcare system that encourage high-quality chronic disease care. Such elements include the community, the health system, self-management support, delivery system design, decision support and clinical information systems. It is a response to powerful evidence that patients with chronic conditions often do not obtain the care they need, and that the healthcare system is not currently structured to facilitate such care.�

Chronic Care Model: Developed by Wagner and colleagues, the primary focus of this model is to include the essential elements of a healthcare system that encourage high-quality chronic disease care. Such elements include the community, the health system, self-management support, delivery system design, decision support and clinical information systems. It is a response to powerful evidence that patients with chronic conditions often do not obtain the care they need, and that the healthcare system is not currently structured to facilitate such care.�

Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM): A group of diverse medical and healthcare systems, practices, and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional, mainstream medicine. The list of what is considered to be CAM changes frequently, as therapies demonstrated to be safe and effective are adopted by conventional practitioners, and as new approaches to health care emerge. Complementary medicine is used with conventional medicine, not as a substitute for it. Alternative medicine is used in place of conventional medicine. Functional medicine is neither complementary nor alternative medicine; it is an approach to medicine that focuses on identifying and ameliorating the underlying causes of disease; it can be used by all practitioners with a Western medical science background and is compatible with both conventional and CAM methods.�

Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM): A group of diverse medical and healthcare systems, practices, and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional, mainstream medicine. The list of what is considered to be CAM changes frequently, as therapies demonstrated to be safe and effective are adopted by conventional practitioners, and as new approaches to health care emerge. Complementary medicine is used with conventional medicine, not as a substitute for it. Alternative medicine is used in place of conventional medicine. Functional medicine is neither complementary nor alternative medicine; it is an approach to medicine that focuses on identifying and ameliorating the underlying causes of disease; it can be used by all practitioners with a Western medical science background and is compatible with both conventional and CAM methods.�

Cytochromes P450 (CYP 450): A large and diverse group of enzymes, most of which function to catalyze the oxidation of organic substances. They are located either in the inner membrane of mitochondria or in the endoplasmic reticulum of cells ans play a critical role in the detoxification of endogenous and exogenous toxins. The substrates of CYP enzymes include metabolic intermediates such as lipids, steroidal hormones, and xenobiotic substances such as drugs.

Cytochromes P450 (CYP 450): A large and diverse group of enzymes, most of which function to catalyze the oxidation of organic substances. They are located either in the inner membrane of mitochondria or in the endoplasmic reticulum of cells ans play a critical role in the detoxification of endogenous and exogenous toxins. The substrates of CYP enzymes include metabolic intermediates such as lipids, steroidal hormones, and xenobiotic substances such as drugs.

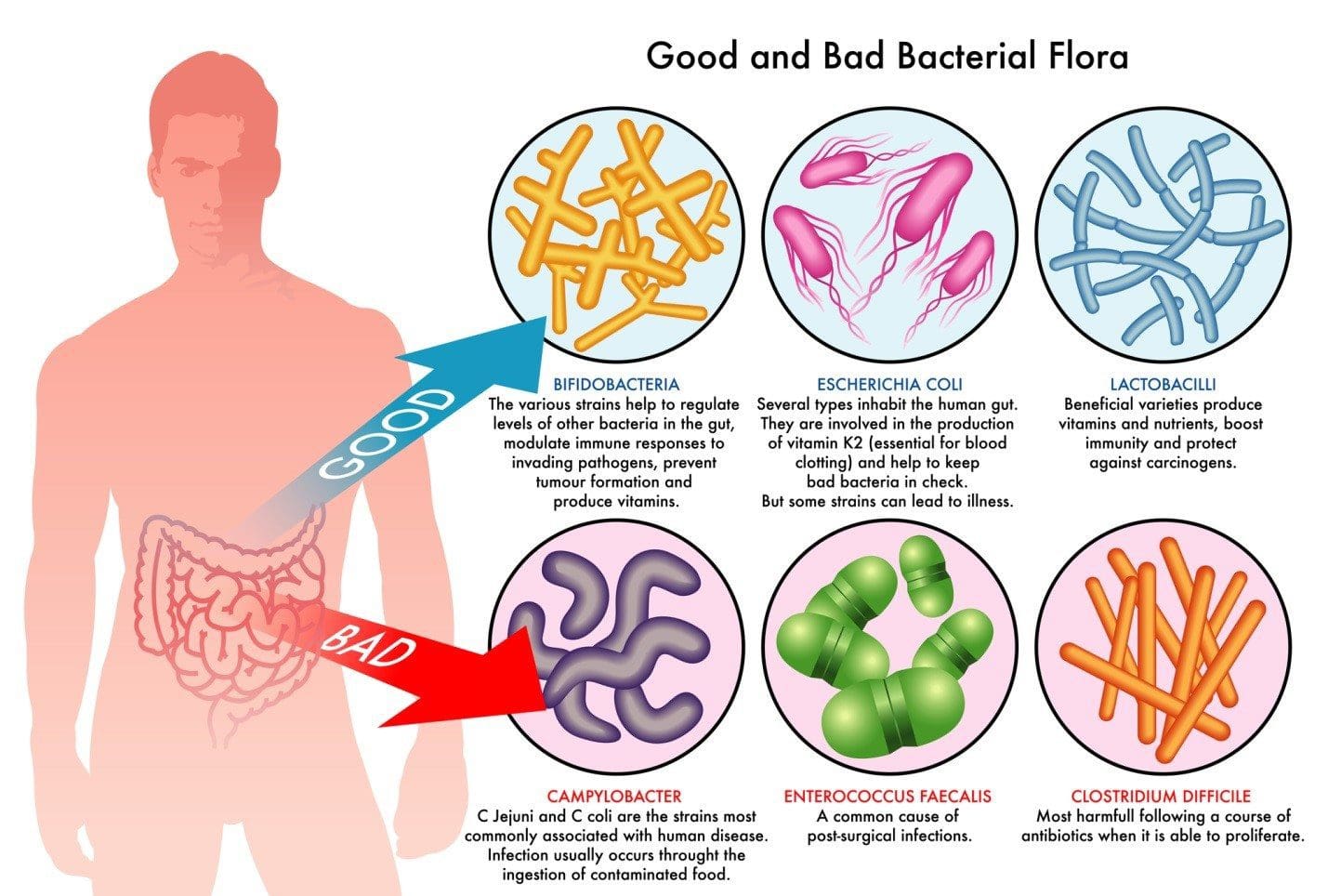

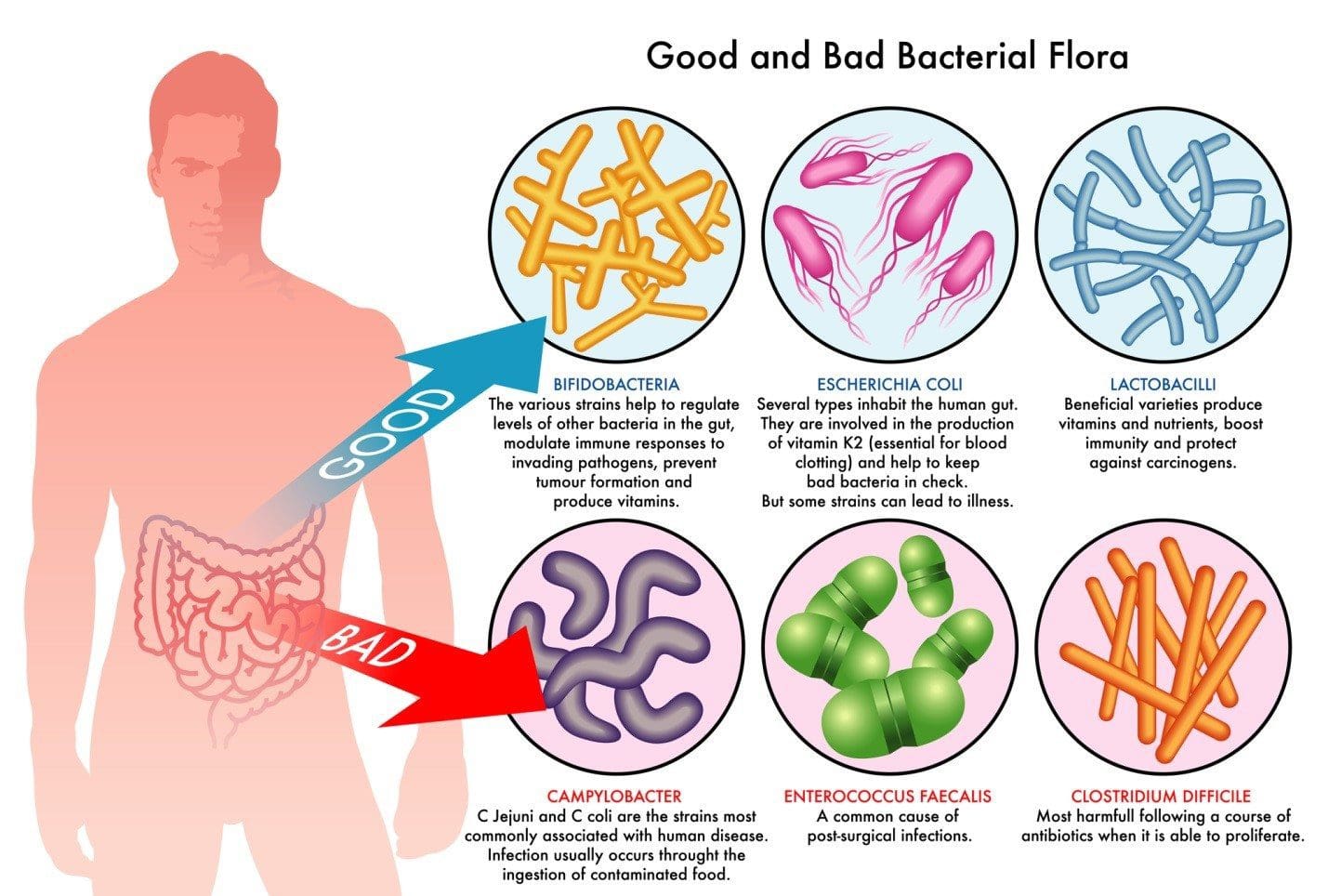

DIGIN: A heuristic mnemonic for assessment of gastrointestinal dysfunction. Thorough assessment of the GI tract should include investigation of the following:

- Digestion/Absorption � Problems with the digestive process including ingestion, chemical digestion, mechanical digestion, absorption, and/or assimilation

- Intestinal Permeability � Permeability of the intestinal barrier: is the epithelium allowing in larger particles in a paracellular manner, making the gut barrier �leaky�?

- Gut Microbiota/Dysbiosis � Changes in composition of the gut flora including balance and interaction of commensal species (See: Dysbiosis)

- Inflammation/Immune � Inflammation and immune activity in the GI tract

- Nervous System � Enteric nervous system function, which controls motility, blood flow, uptake of nutrients, secretion, and immunological and inflammatory processes in the gut.

Dysbiosis: A condition that occurs when the normal symbiosis between gut flora and the host is disturbed and organisms of low intrinsic virulence, which normally coexist peacefully with the host, may promote illness. It is distinct from gastrointestinal infection, in which a highly virulent organism gains access to the gastrointestinal tract and infects the host.�

Dysbiosis: A condition that occurs when the normal symbiosis between gut flora and the host is disturbed and organisms of low intrinsic virulence, which normally coexist peacefully with the host, may promote illness. It is distinct from gastrointestinal infection, in which a highly virulent organism gains access to the gastrointestinal tract and infects the host.�

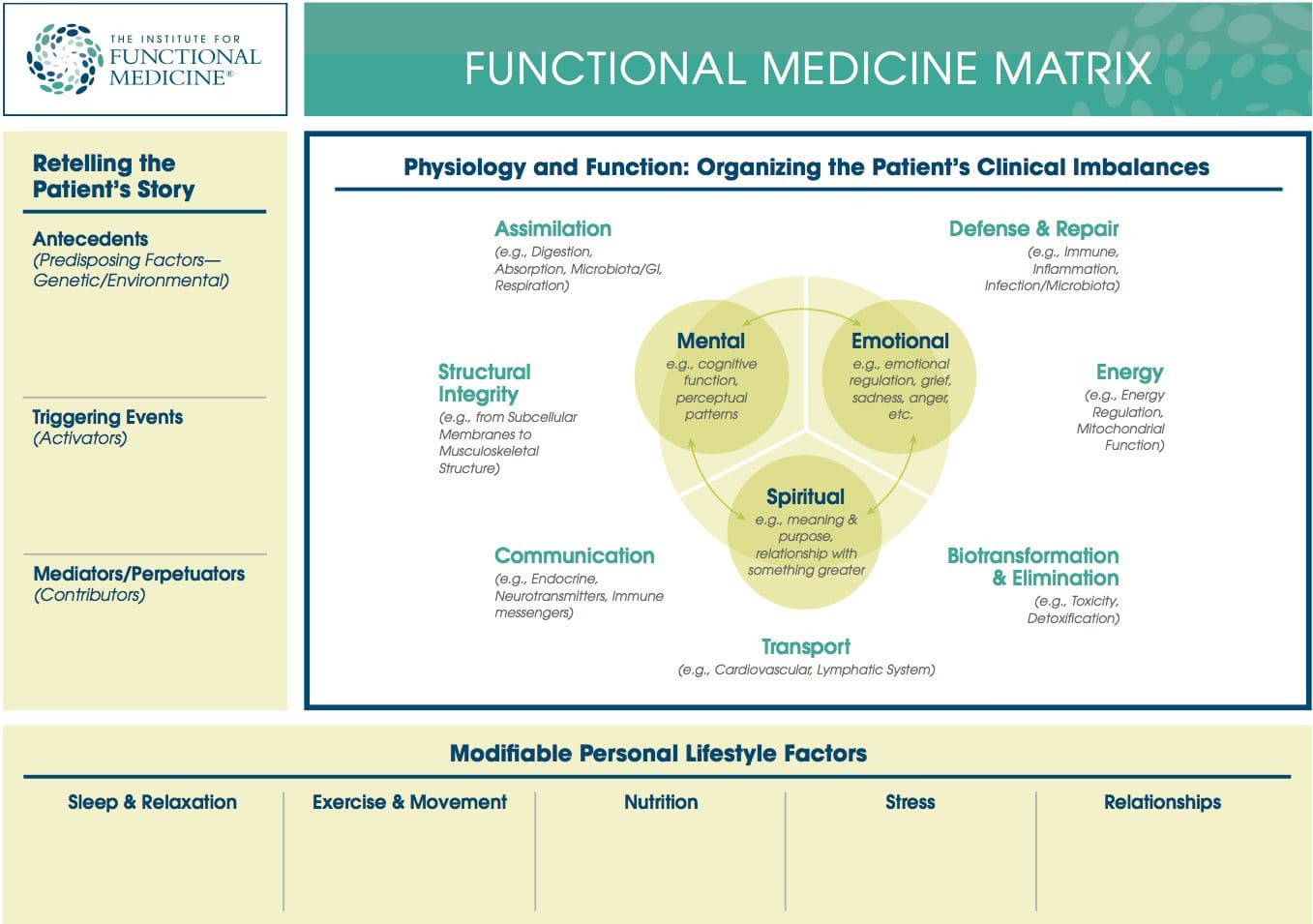

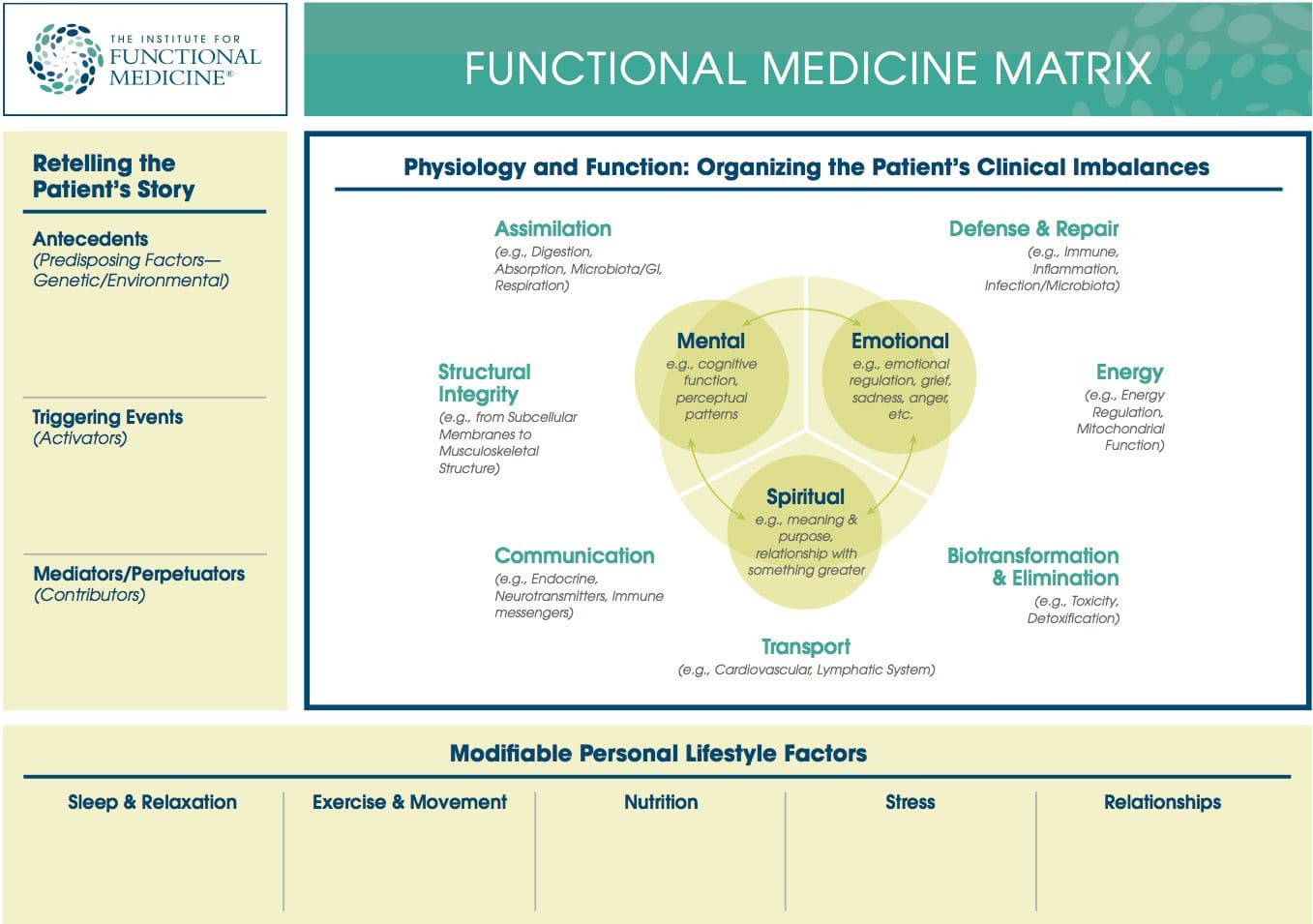

Functional Medicine: A systems-based, science-driven approach to individualized medicine that addresses the underlying causes of disease, using a systems-oriented approach and engaging both patient and practitioner in a therapeutic partnership. It reflects a personalized lifestyle medicine approach and utilizes the Functional Medicine Matrix to organize the patient�s story and determine appropriate interventions for the prevention and treatment of chronic diseases.

Functional Medicine Matrix: The graphic representation of the functional medicine approach, displaying the seven organizing physiological systems, the patient�s known antecedents, triggers, and mediators, and the personalized lifestyle factors that promote health. Practitioners can use the matrix to help organize their thoughts and observations about the patient�s health and decide how to focus therapeutic and preventive strategies.

Functional Medicine Matrix: The graphic representation of the functional medicine approach, displaying the seven organizing physiological systems, the patient�s known antecedents, triggers, and mediators, and the personalized lifestyle factors that promote health. Practitioners can use the matrix to help organize their thoughts and observations about the patient�s health and decide how to focus therapeutic and preventive strategies.

Cytokines: Immunoregulatory proteins (such as interleukin, tumor necrosis factor, and interferon). They may act locally or systemically and tend to have both immunomodulatory and other effects on cellular processes in the body. Cytokines have been used in the treatment of certain cancers.�

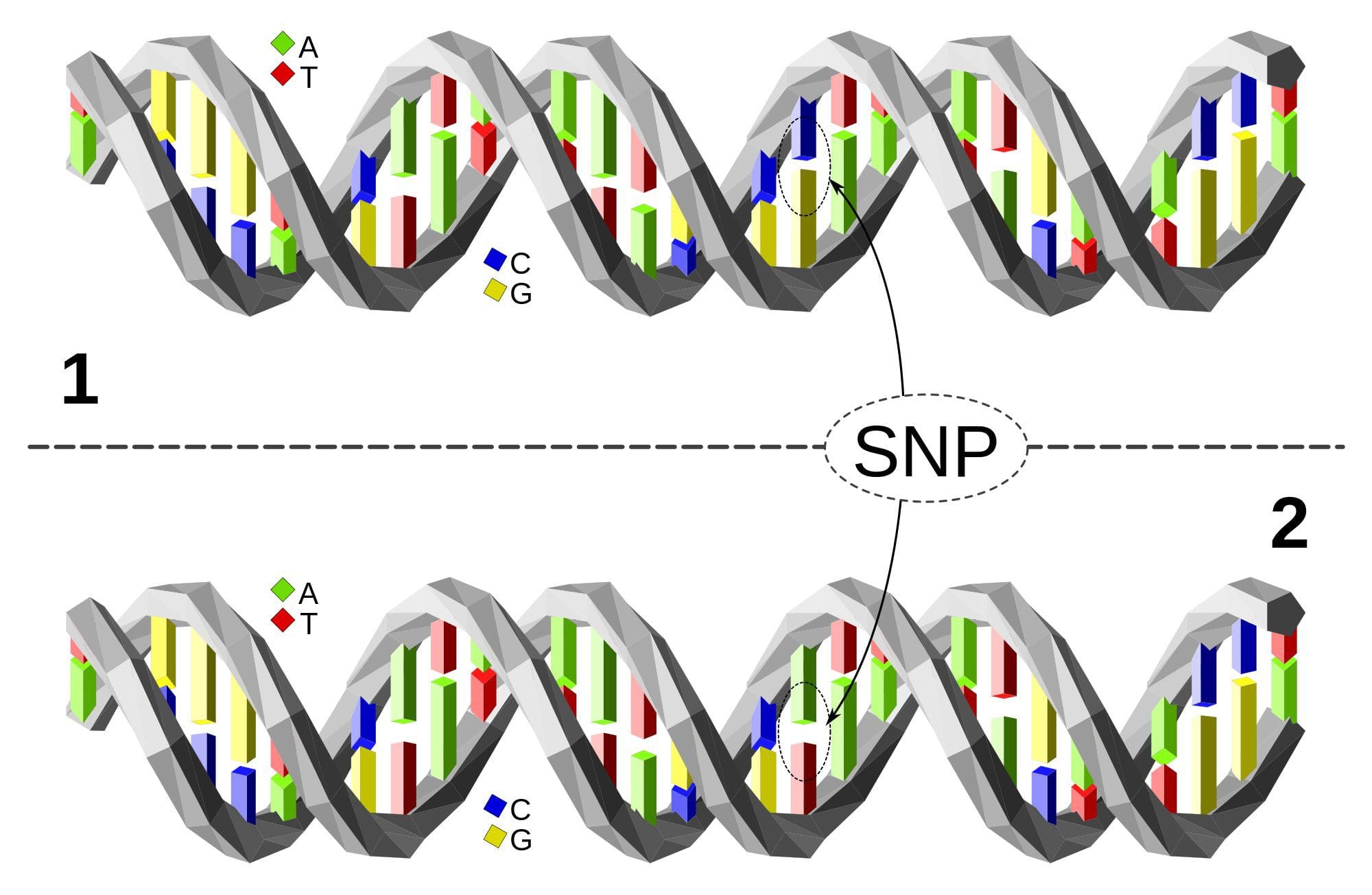

Genomics: The study of the whole genome of organisms, including interactions between loci and alleles within the genome. Research on single genes does not fall into the definition of genomics unless the aim of this functional information analysis is to elucidate the gene�s effect on the entire genome network. Genomics may also be defined as the study of all the genes of a cell, or tissue, at the DNA (genotype), mRNA (transcriptome), or protein (proteome) levels.�

GO-TO-IT: A heuristic mnemonic for the processes involved in the clinical practice of functional medicine:

- Gather oneself and be mindful in preparing to see each patient; gather information through intake forms, questionnaires, the initial consultation, physical exam, and objective data. A detailed functional medicine history that is appropriate to age, gender, and nature of presenting problems is taken.

- Organize the subjective and objective details from the patient�s story within the functional medicine paradigm. Position the patient�s presenting signs and symptoms, along with the details of the case history, on the timeline and Functional Medicine Matrix.

- Tell the story back to the patient in your own words to ensure accuracy and understanding. The re-telling of the patient�s story is a dialogue about the case highlights�including the antecedents, triggers, and mediators identified in the history and correlating them to the timeline and matrix. The patient is asked to correct and amplify the story, engendering a context of true partnership.

- Order and then prioritize the patient�s information:

- Acknowledge patient�s goals

- Address modifiable lifestyle factors

- Sidney Baker�s too much/not enough model: what are the insufficiencies/excesses?

- Identify clinical imbalances or disruptions in the organizing physiological systems of the matrix

- Initiate further functional assessment and intervention based upon the above work:

- Perform further assessment

- Referral to adjunctive care:

- Nutritional professionals

- Lifestyle educators

- Other healthcare providers

- Specialists

- Initiate therapy

- Track assessments, note the effectiveness of the therapeutic approach, and identify clinical outcomes at each visit�in partnership with the patient.

Heuristic: A strategy used for problem solving, learning, and discovery that is experience-based, not algorithmic. When an exhaustive search is impractical, heuristic methods may be used to speed up the process of finding a satisfactory solution. A heuristic is sometimes referred to as a rule of thumb.

Homeostasis and Homeodynamics: The former term describes the tendency of living things to maintain physiological parameters within a narrow range usually considered normal in order to maintain optimal function. Under this definition, disease can be defined as a departure from the homeostatic state. The latter term describes the tendency of homeostatic set points to change throughout an organism�s lifespan, and thus describes how departures from a homeostatic norm can be adaptive (e.g., fever) or pathological, depending on the context.

Integrative Medicine: Medicine that combines treatments from conventional medicine and those from Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) for which there is some high-quality evidence of safety and effectiveness. In a broader sense, it is healing-oriented medicine that takes into account the whole person (body, mind, and spirit), including all aspects of lifestyle, and makes use of all appropriate therapies, both conventional and alternative. The field is more than 10 years old and it is the only one of the emerging models to explicitly encompass the integration of therapeutics that, until recently, were the sole purview of complementary and alternative medicine. Note: functional medicine is different from integrative medicine because functional medicine emphasizes the evaluation of underlying causes of health and dysfunction and organizes assessment and treatment using the Functional Medicine Matrix, the timeline, and GOTOIT.

Lifestyle Medicine: The use of lifestyle interventions such as nutrition, physical activity, stress reduction, and rest to lower the risk for the approximately 70% of modern health problems that are lifestyle-related chronic diseases (such as obesity and type 2 diabetes), or for the treatment and management of disease if such conditions are already present. It is an essential component of the treatment of most chronic diseases and has been incorporated in many national disease management guidelines.

Lifestyle Medicine: The use of lifestyle interventions such as nutrition, physical activity, stress reduction, and rest to lower the risk for the approximately 70% of modern health problems that are lifestyle-related chronic diseases (such as obesity and type 2 diabetes), or for the treatment and management of disease if such conditions are already present. It is an essential component of the treatment of most chronic diseases and has been incorporated in many national disease management guidelines.

Long Latency Disease: Disease that becomes manifest at a time remote from the initial exposure to disease triggers, or that requires continued exposure to triggers and mediators over an extended period of time to manifest frank pathology. Examples include heart disease, cancer, and osteoporosis.�

Mediators: Intermediaries that contribute to the continued manifestations of disease. Mediators do not cause disease; instead, they underlie the host response to triggers. Examples include biochemical factors (e.g., cytokines and leukotrienes) as well as psychosocial ones (e.g., reinforcement for staying ill).�

Metabolomics (or metabonomics): �The study of metabolic responses to drugs, environmental changes and diseases. Metabonomics is an extension of genomics (concerned with DNA) and proteomics (concerned with proteins). Following on the heels of genomics and proteomics, metabonomics may lead to more efficient drug discovery and individualized patient treatment with drugs, among other things.� (From MedicineNet.com)�

Nutrigenomics (or nutritional genomics): The study of how different foods may interact with specific genes to increase the risk of common chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes, obesity, heart disease, stroke, and certain cancers. It can also be described as the study of the influence of genetic variation on nutrition by correlating gene expression or single-nucleotide polymorphisms with a nutrient’s absorption, metabolism, elimination, or biological effects. Nutrigenomics also seeks to provide a molecular understanding of how common chemicals in the diet affect health by altering the expression of genes and the structure of an individual’s genome. The ultimate aim of nutrigenomics is to develop rational means to optimize nutrition for the patient�s genotype.�

Organ Reserve: The difference between the maximal function of a vital organ and the level of function required to maintain an individual�s daily life. In other words, it is the �reserve power� of a particular organ, above and beyond what is required in a healthy individual. It can also be thought of as the degrees of freedom available in the body organs to perform their functions and maintain health. Decline in the organ reserve occurs under stress, during sickness, and as we age.�

Organ System Diagnosis: In the allopathic medical model, it is common to give a collection of symptoms a name based on dysfunction in an organ system, then to cite the named disease as the cause of the symptoms the patient is experiencing. This bit of circular logic avoids any discussion of the systemic or underlying causes of dysfunction and also treats all people with �disease X� the same, despite the fact that two people with the same collection of symptoms may have completely different underlying physiological causes for the symptoms they display.�

Organizing Physiological Systems: To assist clinicians in understanding and applying the complexity of functional medicine, IFM has organized and adapted a set of seven interrelated biological systems that underlie all physiology. Imbalances in these systems or core clinical imbalances are the underlying cause of disease and dysfunction.

- Assimilation (e.g., Digestion, Absorption, Microbiota/GI, Respiration)

- Defense and Repair (e.g., Immune, Inflammation, Infection/Microbiota)

- Energy (e.g., Energy Regulation, Mitochondrial Function)

- Biotransformation and Elimination (e.g., Toxicity, Detoxification)

- Transport (e.g., Circulation, Lymphatic Flow)

- Communication (e.g., Endocrine, Neurotransmitters, Immune messengers)

- Structural Integrity (e.g., from Subcellular Membranes to Musculoskeletal Structure)�

Using this construct, it becomes much clearer that one disease/condition may have multiple causes (i.e., multiple clinical imbalances), just as one fundamental imbalance may be at the root of many seemingly disparate conditions.�

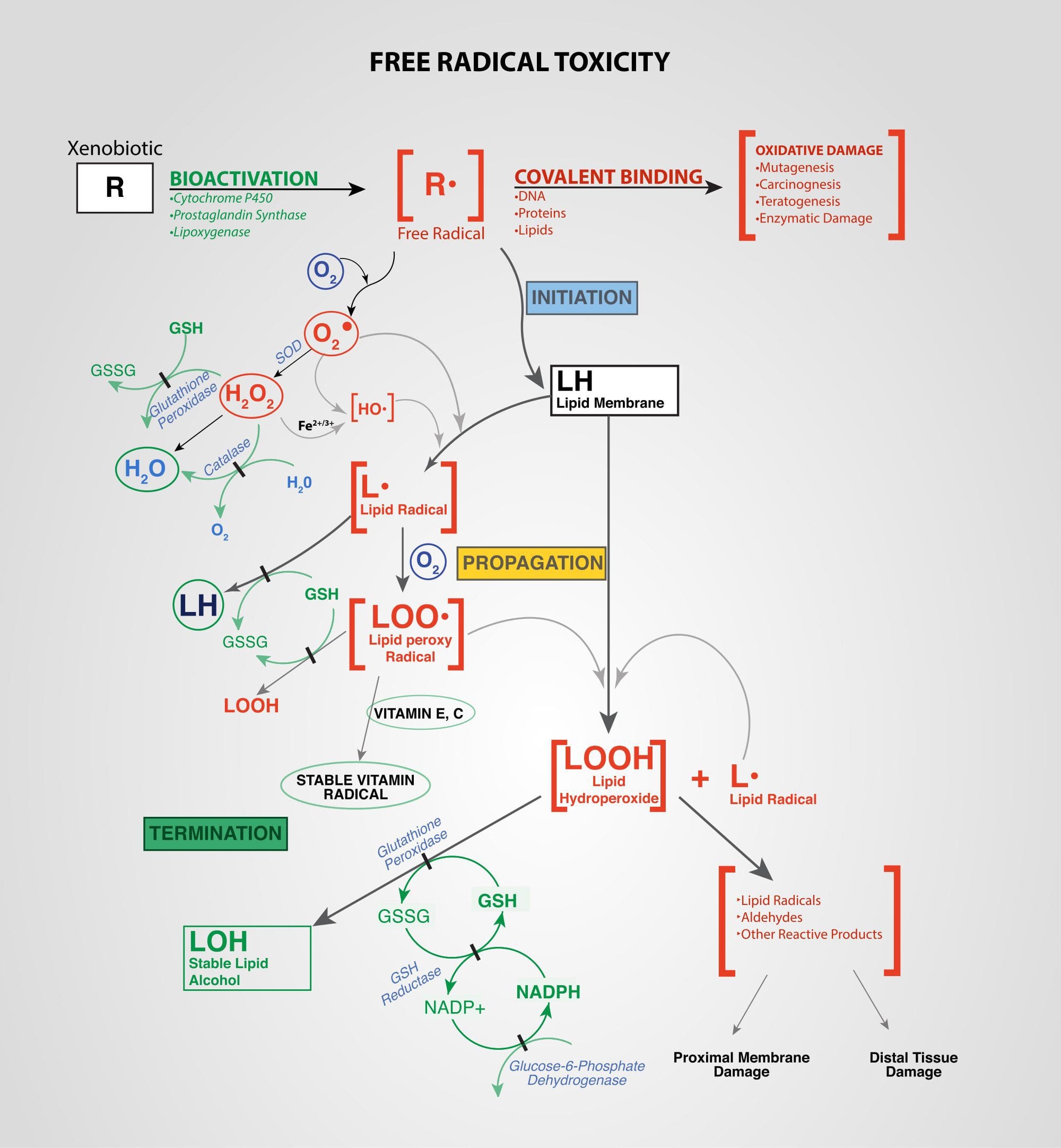

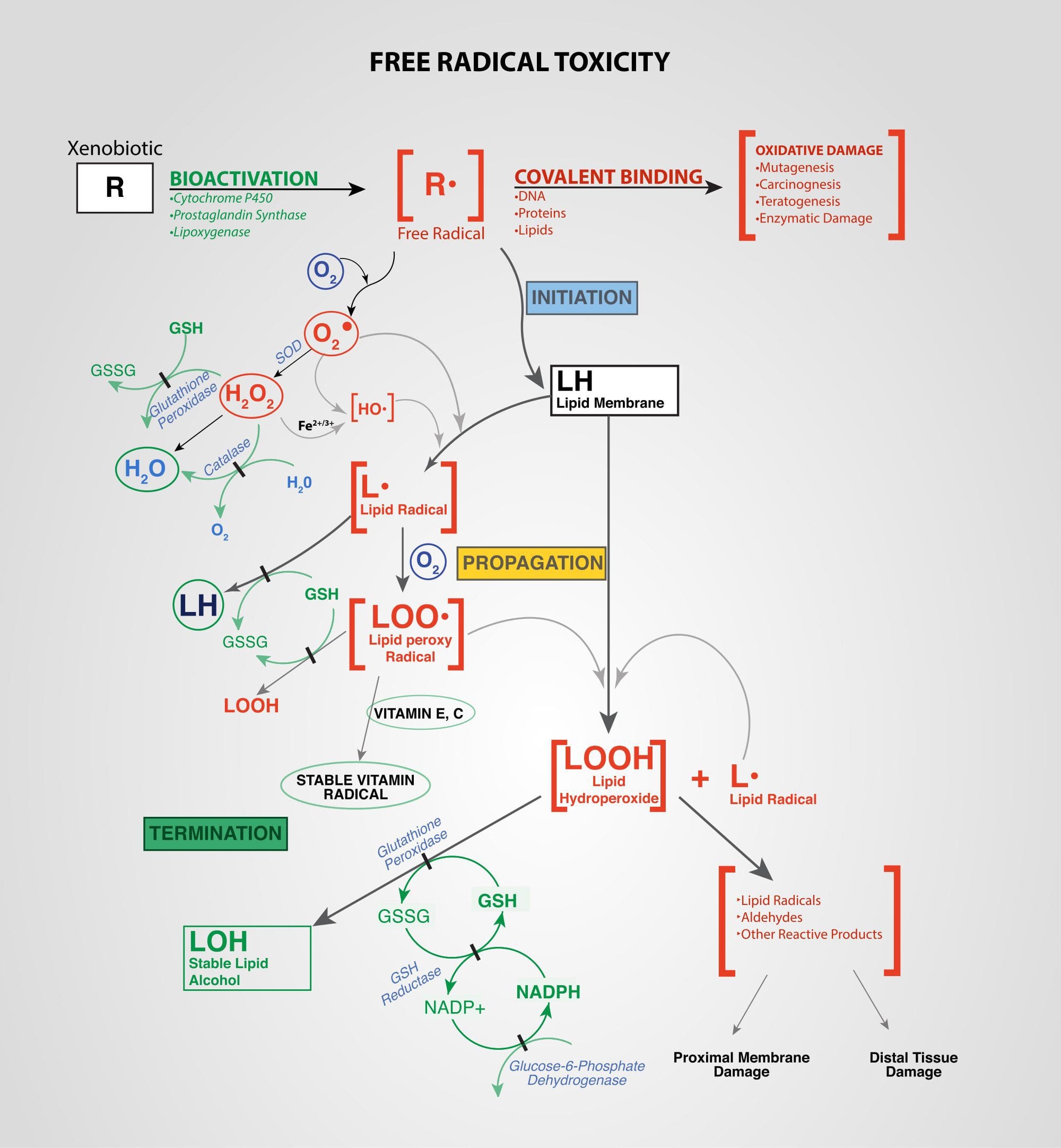

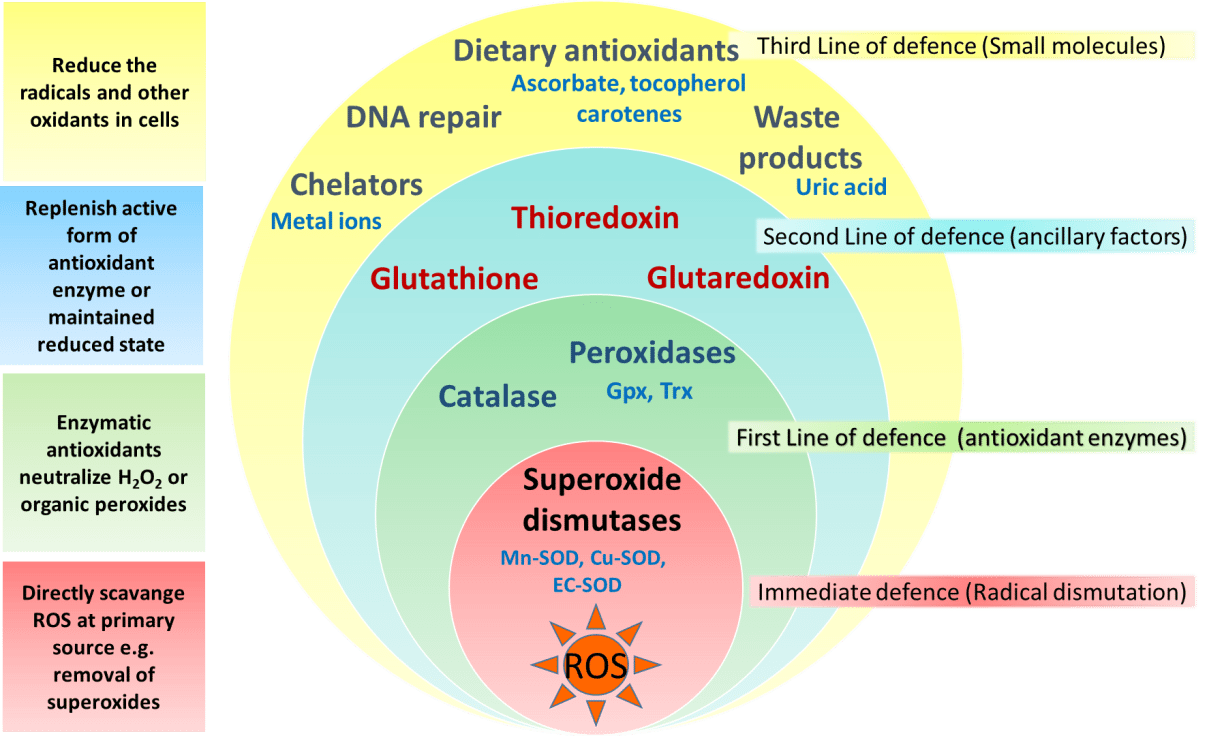

Oxidation-Reduction (also called Redox): Paired chemical reactions that occur in balance with each other within the body of a healthy individual. These reactions involve the transfer of electrons (or the distribution of electron sharing) and thus require both a donor and acceptor. When this physiological parameter is out of balance, a net accumulation of donors or acceptors can lead to deleterious cellular oxidation phenomena (lipid peroxidation, free radical formation).�

Oxidative Stress: Oxidative stress occurs when there is an imbalance between the production of damaging reactive oxygen species and an individual�s antioxidant capacity to detoxify the reactive intermediates or to repair the resulting damage. Disturbances in the normal redox state of tissues can cause toxic effects through the production of peroxides and free radicals that damage all components of the cell, including proteins, lipids, and DNA. Oxidative stress is implicated in the etiology of several chronic diseases including atherosclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and chronic fatigue syndrome.�

Personalized Lifestyle Factors: The modifiable lifestyle factors that appear along the bottom of the Functional Medicine Matrix. Clinicians and their patients can partner to develop an individualized plan for addressing these issues. Health-promoting lifestyle factors include:

- Sleep and Relaxation � Getting adequate sleep and meaningful relaxation time in one�s life

- Exercise and Movement � Participating in physical activity that is appropriate for age and health

- Nutrition and Hydration � Eating a diet that is appropriate for age, genetic background, and environment, as well as maintaining adequate hydration

- Stress and Resilience � Reducing stress levels and managing existing stress

- Relationships and Networks � Developing and maintaining healthy relationships and social networks while reducing the impact of noxious relationships

Personalized (Individualized) Medicine: Personalized medicine can be described as the effort to define and strengthen the art of individualizing health care by integrating the interpretation of patient data (medical history, family history, signs, and symptoms) with emerging ��omic� technologies�nutritional genomics, pharmacogenomics, proteomics, and metabolomics. It is also defined as medicine that treats each patient as a unique individual and takes into account the totality of personal history, family history, environment and lifestyle, physical presentation, genetic background, and mind/body/spirit. Interventions are tailored to each patient and adjusted based on the patient�s individualized response.�

Precipitating Event: Similar to a trigger�a trigger, however, only provokes illness as long as the person is exposed to it (or for a short while afterward), while a precipitating event initiates a change in health status that persists long after the exposure ends

Prospective Medicine (aka: 4-P Medicine): A relatively new concept introduced in 2003, prospective medicine is a descriptive rather than a prescriptive term, encompassing �personalized, predictive, preventive, and participatory medicine.� Snyderman argues persuasively that a comprehensive system of care would address not only new technologies (e.g., identification of biomarkers, use of electronic and personalized health records), but also delivery systems, reimbursement mechanisms, and the needs of a variety of stakeholders (government, consumers, employers, insurers, and academic medicine). Prospective medicine does not claim to stake out new scientific or clinical territory; instead, it focuses on creating an innovative synthesis of technologies and models�particularly personalized medicine (the �-omics�) and systems biology�in order to �determine the risk for individuals to develop specific diseases, detect the disease�s earliest onset, and prevent or intervene early enough to provide maximum benefit.�

Proteomics: The large-scale study of proteins, particularly their structures and functions, how they’re modified, when and where they’re expressed, how they’re involved in metabolic pathways, and how they interact with one another. The proteome is the entire complement of proteins, including the modifications made to a particular set of proteins, produced by an organism or system. This will vary with time and distinct requirements, or stresses, that a cell or organism undergoes. As a result, proteomics is much more complicated than genomics: an organism’s genome is more or less constant, while the proteome differs from cell to cell and from time to time.�

PURE: A heuristic mnemonic for assessment and treatment of toxicity-related disorders. Steps to consider when assessing and treating patients with toxic exposures include:

- Pattern Recognition � Recognize common patterns of toxicity signs and symptoms, including those associated with neurodevelopmental toxicity, immunotoxicity, mitochondrial toxicity, and endocrine toxicity

- Undersupported/Overexposed � Examine the patient�s environment and lifestyle to determine what might be lacking and what there might be too much of

- Reduce Toxin Exposure � Design a strategy for the patient to avoid continued toxin exposure

- Ensure a Safe Detox � Support the patient during detoxification by ensuring adequate nutrients to aid in the detoxification and biotransformation process and by recommending lifestyle changes that increase the safety and efficacy of detox programs.�

PTSD: A heuristic for general treatment of hormone-related disorders. Factors to be considered include:

- Production � Production/synthesis and secretion of the hormone

- What are the building blocks of thyroid hormone and cortisol?

- What affects the secretion of insulin?

- What are the building blocks of serotonin?

- What affects synthesis-inflammation of the gland (as in autoimmune thyroiditis)?

- Transport � Transport/conversion/distribution/ interaction with other hormones

- Do the levels of insulin impact the levels of E or T?

- Does a hormone�s transport from its gland of origin to the target gland impact its effectiveness or toxicity?

- Can we influence the level of free hormone?

- Is the hormone transformed (T4 to T3 or RT3) and can we modulate that?

- Sensitivity � Cellular sensitivity to the hormone signal

- Are there nutritional or dietary factors that influence the cellular response to insulin, thyroid hormones, estrogens, etc.?

- Detoxification � Detoxification/excretion of the hormone. For example:

- How is estradiol metabolized in the process of biotransformation?

- Can we alter it?

- What can we do to affect the binding to and excretion of estrogens?

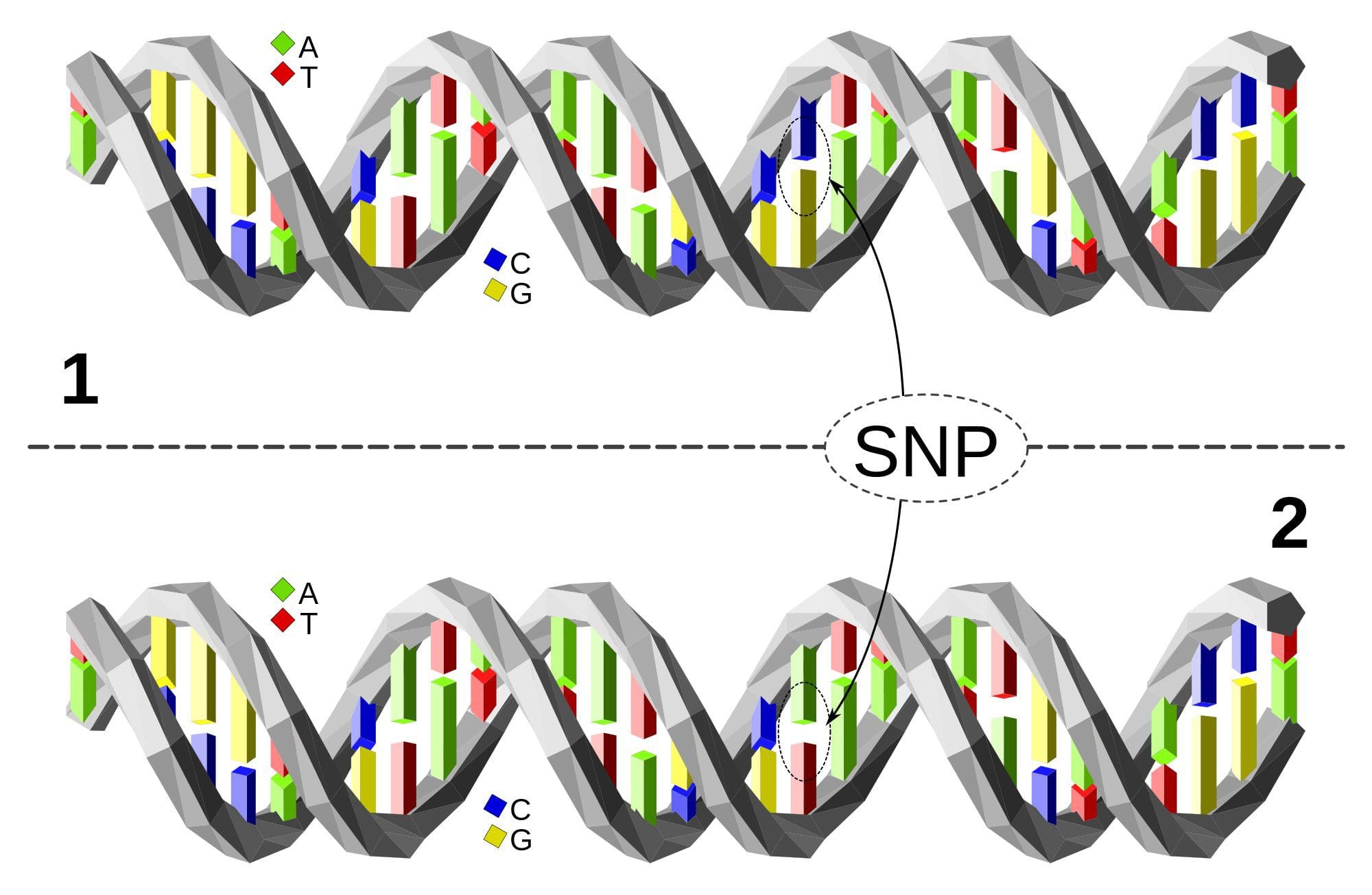

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism or SNP (pronounced �snip�) is a DNA sequence variation occurring when a single nucleotide�A, T, C, or G�in the genome differs between members of a species or between paired chromosomes in an individual. Almost all common SNPs have only two alleles. These genetic variations underlie differences in our susceptibility to, or protection from, several diseases. Variations in the DNA sequences of humans can affect how humans develop diseases. For example, a single base difference in the genes coding for apolipoprotein E is associated with a higher risk for Alzheimer’s disease. SNPs are also manifestations of genetic variations in the severity of illness, the way our body responds to treatments, and the individual response to pathogens, chemicals, drugs, vaccines, and other agents. They are thought to be key factors in applying the concept of personalized medicine.

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism or SNP (pronounced �snip�) is a DNA sequence variation occurring when a single nucleotide�A, T, C, or G�in the genome differs between members of a species or between paired chromosomes in an individual. Almost all common SNPs have only two alleles. These genetic variations underlie differences in our susceptibility to, or protection from, several diseases. Variations in the DNA sequences of humans can affect how humans develop diseases. For example, a single base difference in the genes coding for apolipoprotein E is associated with a higher risk for Alzheimer’s disease. SNPs are also manifestations of genetic variations in the severity of illness, the way our body responds to treatments, and the individual response to pathogens, chemicals, drugs, vaccines, and other agents. They are thought to be key factors in applying the concept of personalized medicine.

Relative Risk: A measure of the strength of the relationship between risk factors and a condition. For example, one could compare the risk of developing cancer in persons with a certain exposure or trait to the risk in persons who do not have this characteristic. Male smokers are about 23 times more likely to develop lung cancer than nonsmokers, so their relative risk is 23. Most relative risks are not this large. For example, women who have a first-degree relative (mother, sister, or daughter) with a history of breast cancer have about twice the risk of developing breast cancer compared to women who do not have this family history.�

Systems Biology: Although there is not yet a universally recognized definition of systems biology, the National Institute of General Medical Services (NIGMS) at NIH provides the following explanation: �A field that seeks to study the relationships and interactions between various parts of a biological system (metabolic pathways, organelles, cells, and organisms) and to integrate this information to understand how biological systems function.�

The 5Rs: A heuristic mnemonic for the five-step process used to normalize gastrointestinal function that is a core element of functional medicine:

- Remove � Removing the source of the imbalance (e.g., pathogens, allergic foods) is the critical first step.

- Replace � Next replace any factors that are missing (e.g., HCL, digestive enzymes)

- Reinoculate � Repopulate the gut with symbiotic bacteria (e.g., lactobacilli, bifidobacteria)

- Repair � Heal damaged gut membranes using, for example, glutamine, fiber, and butyrate

- Rebalance � Modify attitude, diet, and lifestyle of the patient to promote a healthier way of living

Three Legs of the Stool: A framework for practicing functional medicine that includes three parts:

- Retelling the patient�s story with ATMs (antecedents, triggers, and mediators): The clinician collects information from the patient through extensive interaction, then reflects the problem back to the patient in terms of antecedents, triggers, and mediators

- Organizing the clinical imbalances: The clinician organizes the clinical imbalances in the organizing physiological systems and lists them on the Functional Medicine Matrix.

- Personalized lifestyle factors: The clinician assesses each patient�s environment and lifestyle, and partners with patients to help them develop, adopt, and maintain appropriate personalized health-promoting behaviors.�

Timeline: A tool that allows clinicians to visualize a patient�s story chronologically by organizing important life events and health issues from pre-conception to the present.

Triage Theory: Linus Pauling Award winner Bruce Ames� theory that DNA damage and late onset disease are consequences of a �triage allocation mechanism� developed during evolution to cope with periods of micronutrient shortage. When micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) are scarce, they are consumed for short-term survival at the expense of long-term survival. In 2009, Children�s Hospital and Research Center Oakland concluded that triage theory explains how diseases associated with aging like cancer, heart disease, and dementia (and the pace of aging itself) may be unintended consequences of mechanisms developed during evolution to protect against episodic vitamin/mineral shortages.

Triage Theory: Linus Pauling Award winner Bruce Ames� theory that DNA damage and late onset disease are consequences of a �triage allocation mechanism� developed during evolution to cope with periods of micronutrient shortage. When micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) are scarce, they are consumed for short-term survival at the expense of long-term survival. In 2009, Children�s Hospital and Research Center Oakland concluded that triage theory explains how diseases associated with aging like cancer, heart disease, and dementia (and the pace of aging itself) may be unintended consequences of mechanisms developed during evolution to protect against episodic vitamin/mineral shortages.

Triggers: Triggers are discrete entities or events that provoke disease or its symptoms (e.g., microbes). Triggers are usually insufficient in and of themselves for disease formation, however, because the health of the host and the vigor of its response to a trigger are essential elements.

Xenobiotics: Chemicals found in an organism that are not normally produced by or expected to be present in that organism. This may also include substances present in much higher concentrations than usual. The term xenobiotics is often applied to pollutants such as dioxins and polychlorinated biphenyls, because xenobiotics are understood as substances foreign to an entire biological system, i.e. artificial substances that did not exist in nature before their synthesis by humans. Exposure to several types of xenobiotics has been implicated in cancer risk.

Xenobiotics: Chemicals found in an organism that are not normally produced by or expected to be present in that organism. This may also include substances present in much higher concentrations than usual. The term xenobiotics is often applied to pollutants such as dioxins and polychlorinated biphenyls, because xenobiotics are understood as substances foreign to an entire biological system, i.e. artificial substances that did not exist in nature before their synthesis by humans. Exposure to several types of xenobiotics has been implicated in cancer risk.

A Healthier You

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Chiropractic, Physical Rehabilitation, PUSH-as-Rx, Spine Care

El Paso, TX. Chiropractor, Dr. Alex Jimenez welcomes all to the new clinic location grand opening!

Grand Opening: Injury Medical Chiropractic Clinic

El Paso, TX, INJURY MEDICAL & CHIROPRACTIC CLINIC announces its newest east side location at 11860 Vista Del Sol, Suite 128 will officially open. The clinic is located in The Mission Business Center near Walgreens.

El Paso, TX, INJURY MEDICAL & CHIROPRACTIC CLINIC announces its newest east side location at 11860 Vista Del Sol, Suite 128 will officially open. The clinic is located in The Mission Business Center near Walgreens.

Injury Medical & Chiropractic Clinic offers an innovative, patient-friendly experience that allows patients access to affordable, quality chiropractic care. Appointments are not necessary, however in order to avoid waiting time appointments are recommended.

11860 Vista Del Sol Dr.�Suite 128

El Paso, Texas 79936

United States (US)

Phone: 1-915-850-0900

Secondary phone: 1-915-412-6677

Fax: 1-866-574-1352

Email: [email protected]

URL:�www.dralexjimenez.com

Monday 9:00 AM – 7:00 PM

Tuesday 9:00 AM – 7:00 PM

Wednesday 9:00 AM – 7:00 PM

Thursday 9:00 AM – 7:00 PM

Friday 9:00 AM – 12:00 PM

Saturday – Sunday Closed

About: Injury Medical & Chiropractic Clinic

Based in El Paso, TX Injury Medical & Chiropractic Clinic is reinventing chiropractic by making quality care convenient and affordable for patients seeking pain relief and ongoing wellness. Extended hours and three convenient locations make care more accessible. Injury Medical & Chiropractic Clinic is an emerging company and key leader in the chiropractic profession. For more information, visit www.dralexjimenez.com, follow us on�Twitter @dralexjimenez�and find us on�Facebook, and�LinkedIn.

Based in El Paso, TX Injury Medical & Chiropractic Clinic is reinventing chiropractic by making quality care convenient and affordable for patients seeking pain relief and ongoing wellness. Extended hours and three convenient locations make care more accessible. Injury Medical & Chiropractic Clinic is an emerging company and key leader in the chiropractic profession. For more information, visit www.dralexjimenez.com, follow us on�Twitter @dralexjimenez�and find us on�Facebook, and�LinkedIn.

I thank you and have a special and respectful message�

God loves motion.�God has created a fantastic design in all of us. His love of joints and articulations is obvious. Simply put, as an observer, our creator would have not given us so many joints with so many functions. So again, I repeat, God loves motion. Therefore, it is not just a choice to take care of them,�it is our obligation. I will help everybody I meet and treat to move better while�freeing themselves of any joint limitation preventing the full expression of life.

With a bit of work, we can achieve optimal health together. I look forward in doing my absolute best and helping those in need. It is what my mentors taught me, it is what I teach and it is what I will do passionately until�my last breath.

God Bless

Dr. Alex Jimenez D.C.,C.C.S.T

Fitness Facility & Chiropractic Clinic: PUSH-as-Rx

Our top rated�PUSH as Rx chiropractic clinic/fitness center will be open, but will be for physical rehabilitation and supplements.

Central Location:

Next to Guitar Center

6440 Gateway East Bldg. B

El Paso, TX 79905

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Athletes, PUSH-as-Rx, Sports Injuries

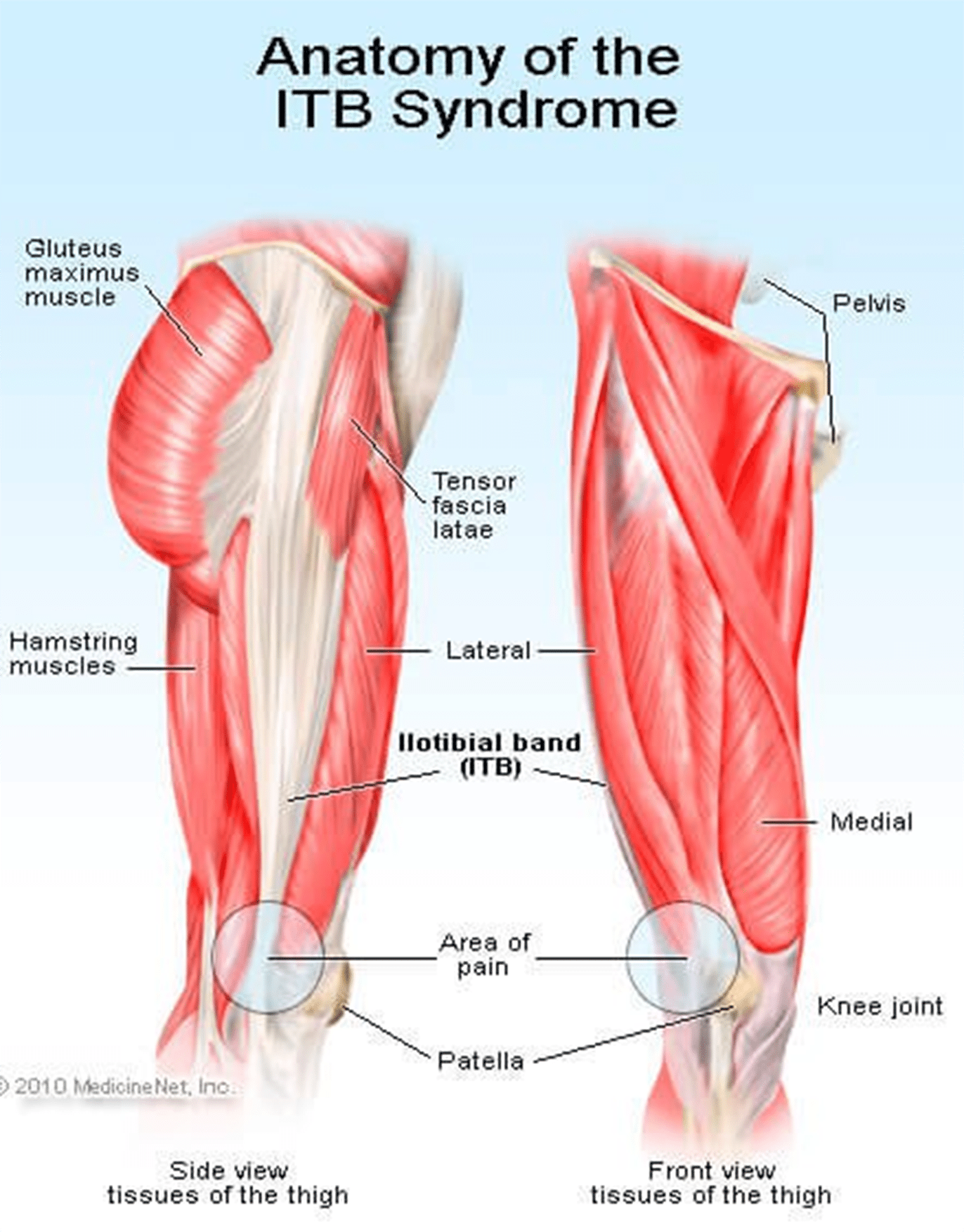

El Paso, TX. Chiropractor, Dr. Jimenez takes a look at top running shoes that are great for knee pain and Iliotibial (IT) Band Syndrome.

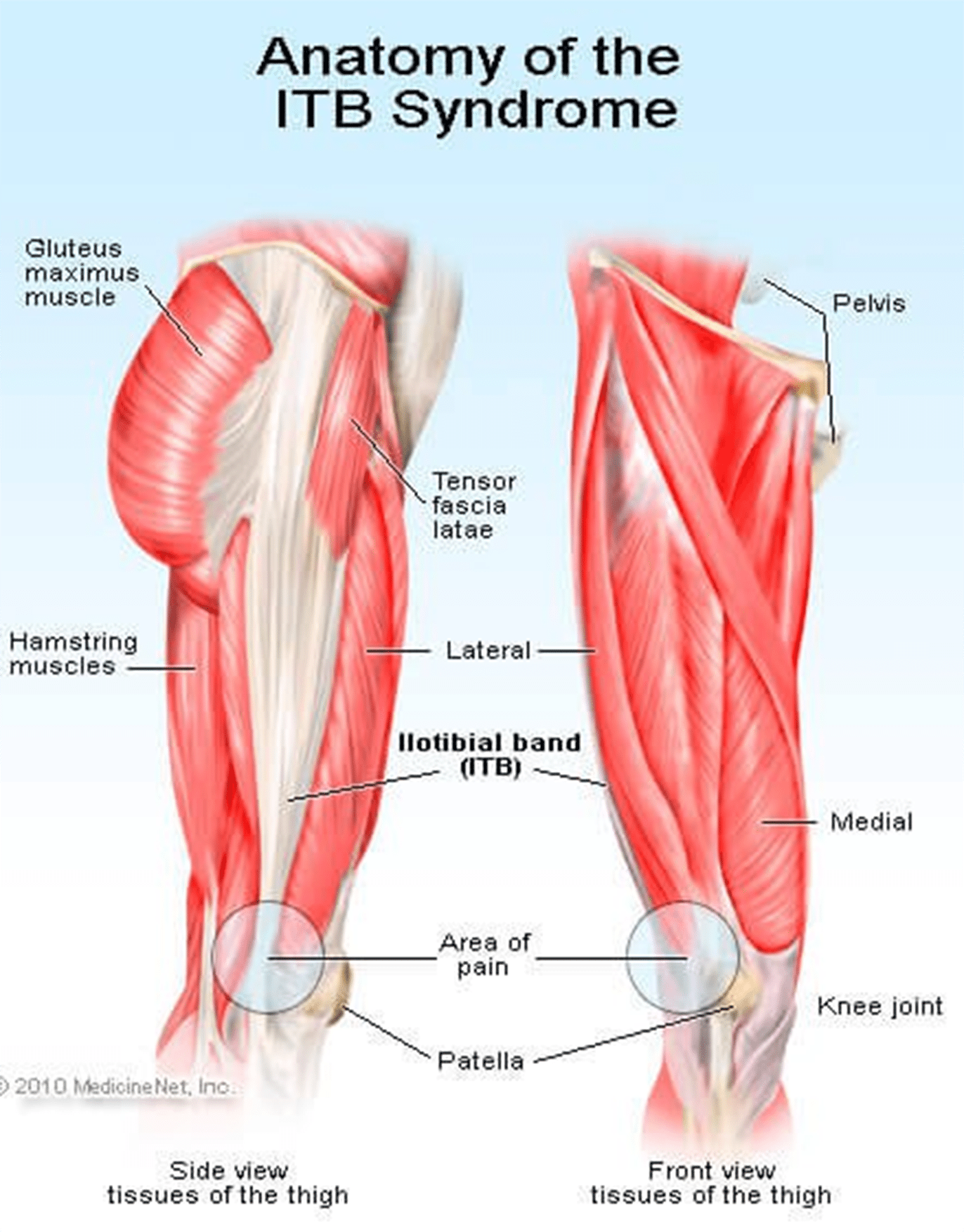

Running Shoes: Knee pain is one of the common problems with most active people. It could get worse for those who love running, especially the athletes. A majority of them suffer from knee pains each year. This pain hinders you from enjoying your daily sports activities and might even become worse with time if not treated correctly. There are causes and cures for such pains that this article is going to look at, but the main focus is on the best shoes for knee pain, also referred to as Iliotibial (IT) Band Syndrome.

This can happen due to various causes like overtraining, running many hills, and wrong running form, among others. These injuries are very frustrating as they can take up to months to go away. This is the reason different companies have designed shoes that will offer you support for any knee problem.

What Goes Wrong

The iliotibial band (ITB) is usually a structure whose job is to provide leg stability whenever you take a step. It works with the hip muscles in a thigh’s outward movement and also helps counter the movements within the knee joint. This band starts in the hip and ends just under the knee joint.

Repeated use of the ITB leads to stress, causing knee pain. You will also notice clicking sensations from the joint as ITB snaps across it. This pain is always experienced when the heel comes into contact with the ground; running slowly or downhill tends to make the symptoms worse.

ITBS will usually start as tightness while running but continues to a point where the pain is severe and unbearable. Although ITB continues to tighten when overstressed or injured from training, this is not the main problem. What causes the injury is how the ITB functions and the weakness around it.

The ITB is generally a weak structure and any weakness around it will lead to injury. Most runners have weak core muscles due to the fact that they don’t do strength training or have never been in any sports with side-to-side movement.

Signs Of IT Band Syndrome

Signs Of IT Band Syndrome

If you are a runner, you will be able to distinguish ITBS by:

If you are a runner, you will be able to distinguish ITBS by:

- A swelling

- A cracking feeling when stretching the knee

- A feeling of burning, stinging and aching on the outer side of the knee that might migrate to the thigh. You will notice these discomforts especially, on your second half of the run.

- Bending the knee at 45 degrees causes severe external knee pain

Criteria You Should Follow When Selecting The Best Running Shoes for ITBS

?There are various things that you should always consider when buying running shoes. Since most runners experience knee pain, it is wise to look for shoes that will help alleviate this pain without slowing them down. Below are some of the features to look out for in running shoes:

Stability/ Support

Since it is common to have knee pains due to lack of motion control and lack of stability, it is good to choose shoes that will offer you the support you need while running. If your running shoes don’t have any stability, you will end up stressing out your knee, which will result in pain and discomfort while running.

Fit

If you want to do away with pain, you might consider looking for a fit pair of shoes as they will reduce any pain, causing issues in the long run. Pay attention to small specifics like shoes that offer enough heel space, sufficient toe box room, and enough space for wide feet. Your toes should be able to move freely without being constricted.

If you want to do away with pain, you might consider looking for a fit pair of shoes as they will reduce any pain, causing issues in the long run. Pay attention to small specifics like shoes that offer enough heel space, sufficient toe box room, and enough space for wide feet. Your toes should be able to move freely without being constricted.

If your foot cannot move freely and the toes are restricted from spreading, it could lead to painful issues in your feet, legs, and knees.

Motion control footwear is not the whole solution; you need to ensure your feet can still function naturally as they are supposed to.

Comfort

No one wants to wear uncomfortable shoes! Each of these selected best shoes come with upper and underfoot comforts to ensure you get to enjoy your run.

Most of these shoes are made with DNA technology, Gel cushioning, and REVlite midsole for ultimate comfort.

Durability

Your running shoes should run their course without falling apart as this will cause you pain in the long-run. If they promise to offer you support, they should do just that and not start peeling off and tearing when you are on the run.

The ??below 5 shoes have passed the durability test to ensure they give you maximum performance.

Breathability

Although this has nothing to do with knees, it is paramount that your running shoes have enough breathing space to avoid accumulating excess moisture, which might bring discomfort and other feet related problems.

There is no magical cure for knee pain and you should always know the root cause. This way, you will be able to come up with the best solution of minimizing or even eliminating the pain entirely. Although there are various causes of knee pain, this article is focusing on ITB syndrome which happens to be one of the causes.

Reviews Of The Top 5 Shoes

These shoes have been selected with the runner’s welfare in mind. They will help deal with the ITBS, which is a problem for most of them. Since one way of dealing with this condition is getting good running shoes, here is a review of such products.

Asics Gel Kayano 23

This upgraded version is lightweight to help with any knee problems. It offers you comfort through cushioning that help absorb shock as you run as well as other features like grip, fit, and durability. The shoe has an added outer sole to ensure it lasts you as long as possible.

This upgraded version is lightweight to help with any knee problems. It offers you comfort through cushioning that help absorb shock as you run as well as other features like grip, fit, and durability. The shoe has an added outer sole to ensure it lasts you as long as possible.

PROS

- ?Gel cushioning will act as a shock absorber for more comfort

- ?Has superb breathability feature

- ?Is ideal for overpronation and knee pain

- ?The outsole’s traction will offer the intended support on various surfaces

CONS

New Balance 890v5

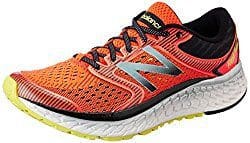

It tops the list of 5 best running shoes. Also, it has remained the first choice for most runners with knee pain issues. This pair offers all the above functionalities too, making it your best choice.

It tops the list of 5 best running shoes. Also, it has remained the first choice for most runners with knee pain issues. This pair offers all the above functionalities too, making it your best choice.

PROS

- ?It comes with one of a kind breathability and fit due to its great FantomFit design

- ?Its smooth upper construction will ensure no irritation occurs

- ?The REVlite midsole will give you much needed cushioning

CONS

- ?It has a narrow toe box and might not fit a person with a wide foot

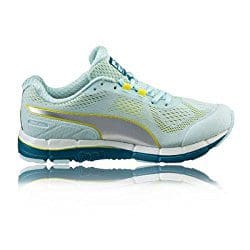

?Puma Faas 600 V3

Puma models have never disappointed, and this one is no exception. Puma Faas 600 is the solution to your knee pain. It is also an affordable option for the short-handed.

Puma models have never disappointed, and this one is no exception. Puma Faas 600 is the solution to your knee pain. It is also an affordable option for the short-handed.

PROS

- ?Great breathability

- ?Comes at a reasonable price

- ?It’s lacing system and fit offers you a secure and comfortable run

- ?It is designed to fit perfectly

CONS

- ?There have been reported concerns about the outsole’s durability

New Balance 1080v7

This is another great choice on the list. It is one of the New Balance Fresh Foam Series. Its midsole offers you the required support coupled with comfort to eliminate knee pains.

This is another great choice on the list. It is one of the New Balance Fresh Foam Series. Its midsole offers you the required support coupled with comfort to eliminate knee pains.

PROS

- ?Very durable

- ?Enough breathability for long runs

- ?Good amount of cushioning and support from the Fresh Foam midsole

- ?It fits like a sock giving you a confident use

CONS

- ?The upper design is not seamless

- ?Can be stiff

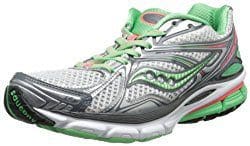

Saucony Hurricane 16

This is the 16th edition of the Saucony Hurricane, which offers a combination of steadiness and protection. Those with knee pain have agreed with the stability offered by this shoe. It is also cushioned to help you go for long runs without any pain or injury. It is perfect for heavy runners and those who are out of shape due to inactivity.

This is the 16th edition of the Saucony Hurricane, which offers a combination of steadiness and protection. Those with knee pain have agreed with the stability offered by this shoe. It is also cushioned to help you go for long runs without any pain or injury. It is perfect for heavy runners and those who are out of shape due to inactivity.

PROS

- ?Superb stability

- ?Lightweight rubber offers protection and cushioning

- ?Great ground contact

- ?Reflective parts allow you to have a safe run

- ?Comes with Sauc-Fit Technology that enhances its comfortability

CONS

- ?It is a bit narrow

- ?Limited colors to choose from

- ?Might be heavy for fast runners

If you are a long-distance runner, it is good to know that your shoes cushioning will wear out quite easily and you might be tempted to continue using them since they look good on the outside. This is a big mistake. The following will help you prevent any more ITBS recurrences:

- Replace running shoes frequently to avoid wearing those with worn out inner cushioning

- Always give your shoes time to rest so that the cushioning can get restored; it would be wise to have two pairs of running shoes.

Although shoes can offer you relief from ITBS, it is better to look out for other ways of helping you cope with or eliminate the pain entirely. Also, know what triggers the problem and avoid it at all costs.

These shoes have been tried and tested and found to offer support and help in managing the iliotibial band syndrome. Asics takes the lead on these best shoes. It comes with gel cushioning that will offer you the best shock absorption and maximum comfort as seen above. Its sole is also made to help you tackle any terrain and you can be assured that your knees will thank you later. The only drawback is the price, which is on the upper-side. However, always remember that cheap is expensive.

If you are an active person or an athlete suffering from ITBS, go ahead and get yourself a pair of these shoes as per your preference and choice.

in running

Zoey Miller

Hey there, I’m Zoey, founder and the main editor of The Babble Out. I know nobody’s life is smooth as they wish, and it�s the same with mine. I had some terrible news a few years ago and running was the way I got through these issues. This has given me enough motivation to create this blog, so that I can give you a helping hand for as many daily problems as I can. If you are curious why “babble out” is the? name of the blog, then check the “About” page and find out more about me.

We usually talk of energy in general terms, as in �I don�t have a lot of energy today� or �You can feel the energy in the room.� But what really is energy? Where do we get the energy to move? How do we use it? How do we get more of it? Ultimately, what controls our movements? The three metabolic energy pathways are the�phosphagen system, glycolysis�and the�aerobic system.�How do they work, and what is their effect?

We usually talk of energy in general terms, as in �I don�t have a lot of energy today� or �You can feel the energy in the room.� But what really is energy? Where do we get the energy to move? How do we use it? How do we get more of it? Ultimately, what controls our movements? The three metabolic energy pathways are the�phosphagen system, glycolysis�and the�aerobic system.�How do they work, and what is their effect? The energy for all physical activity comes from the conversion of high-energy phosphates (adenosine�triphosphate�ATP) to lower-energy phosphates (adenosine�diphosphate�ADP; adenosine�monophosphate�AMP; and inorganic phosphate, Pi). During this breakdown (hydrolysis) of ATP, which is a water-requiring process, a proton, energy and heat are produced: ATP + H2O ���ADP + Pi�+ H+�+ energy + heat. Since our muscles don�t store much ATP, we must constantly resynthesize it. The hydrolysis and resynthesis of ATP is thus a circular process�ATP is hydrolyzed into ADP and Pi, and then ADP and Pi�combine to resynthesize ATP. Alternatively, two ADP molecules can combine to produce ATP and AMP: ADP + ADP ���ATP + AMP.

The energy for all physical activity comes from the conversion of high-energy phosphates (adenosine�triphosphate�ATP) to lower-energy phosphates (adenosine�diphosphate�ADP; adenosine�monophosphate�AMP; and inorganic phosphate, Pi). During this breakdown (hydrolysis) of ATP, which is a water-requiring process, a proton, energy and heat are produced: ATP + H2O ���ADP + Pi�+ H+�+ energy + heat. Since our muscles don�t store much ATP, we must constantly resynthesize it. The hydrolysis and resynthesis of ATP is thus a circular process�ATP is hydrolyzed into ADP and Pi, and then ADP and Pi�combine to resynthesize ATP. Alternatively, two ADP molecules can combine to produce ATP and AMP: ADP + ADP ���ATP + AMP. During short-term, intense activities, a large amount of power needs to be produced by the muscles, creating a high demand for ATP. The phosphagen system (also called the ATP-CP system) is the quickest way to resynthesize ATP (Robergs & Roberts 1997). Creatine phosphate (CP), which is stored in skeletal muscles, donates a phosphate to ADP to produce ATP: ADP + CP ���ATP + C. No carbohydrate or fat is used in this process; the regeneration of ATP comes solely from stored CP. Since this process does not need oxygen to resynthesize ATP, it is anaerobic, or oxygen-independent. As the fastest way to resynthesize ATP, the phosphagen system is the predominant energy system used for all-out exercise lasting up to about 10 seconds. However, since there is a limited amount of stored CP and ATP in skeletal muscles, fatigue occurs rapidly.

During short-term, intense activities, a large amount of power needs to be produced by the muscles, creating a high demand for ATP. The phosphagen system (also called the ATP-CP system) is the quickest way to resynthesize ATP (Robergs & Roberts 1997). Creatine phosphate (CP), which is stored in skeletal muscles, donates a phosphate to ADP to produce ATP: ADP + CP ���ATP + C. No carbohydrate or fat is used in this process; the regeneration of ATP comes solely from stored CP. Since this process does not need oxygen to resynthesize ATP, it is anaerobic, or oxygen-independent. As the fastest way to resynthesize ATP, the phosphagen system is the predominant energy system used for all-out exercise lasting up to about 10 seconds. However, since there is a limited amount of stored CP and ATP in skeletal muscles, fatigue occurs rapidly. Glycolysis is the predominant energy system used for all-out exercise lasting from 30 seconds to about 2 minutes and is the second-fastest way to resynthesize ATP. During glycolysis, carbohydrate�in the form of either blood glucose (sugar) or muscle glycogen (the stored form of glucose)�is broken down through a series of chemical reactions to form pyruvate (glycogen is first broken down into glucose through a process called�glycogenolysis). For every molecule of glucose broken down to pyruvate through glycolysis, two molecules of usable ATP are produced (Brooks et al. 2000). Thus, very little energy is produced through this pathway, but the trade-off is that you get the energy quickly. Once pyruvate is formed, it has two fates: conversion to lactate or conversion to a metabolic intermediary molecule called acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA), which enters the mitochondria for oxidation and the production of more ATP (Robergs & Roberts 1997). Conversion to lactate occurs when the demand for oxygen is greater than the supply (i.e., during anaerobic exercise). Conversely, when there is enough oxygen available to meet the muscles� needs (i.e., during aerobic exercise), pyruvate (via acetyl-CoA) enters the mitochondria and goes through aerobic metabolism.

Glycolysis is the predominant energy system used for all-out exercise lasting from 30 seconds to about 2 minutes and is the second-fastest way to resynthesize ATP. During glycolysis, carbohydrate�in the form of either blood glucose (sugar) or muscle glycogen (the stored form of glucose)�is broken down through a series of chemical reactions to form pyruvate (glycogen is first broken down into glucose through a process called�glycogenolysis). For every molecule of glucose broken down to pyruvate through glycolysis, two molecules of usable ATP are produced (Brooks et al. 2000). Thus, very little energy is produced through this pathway, but the trade-off is that you get the energy quickly. Once pyruvate is formed, it has two fates: conversion to lactate or conversion to a metabolic intermediary molecule called acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA), which enters the mitochondria for oxidation and the production of more ATP (Robergs & Roberts 1997). Conversion to lactate occurs when the demand for oxygen is greater than the supply (i.e., during anaerobic exercise). Conversely, when there is enough oxygen available to meet the muscles� needs (i.e., during aerobic exercise), pyruvate (via acetyl-CoA) enters the mitochondria and goes through aerobic metabolism. Since humans evolved for aerobic activities (Hochachka, Gunga & Kirsch 1998; Hochachka & Monge 2000), it�s not surprising that the aerobic system, which is dependent on oxygen, is the most complex of the three energy systems. The metabolic reactions that take place in the presence of oxygen are responsible for most of the cellular energy produced by the body. However, aerobic metabolism is the slowest way to resynthesize ATP. Oxygen, as the patriarch of metabolism, knows that it is worth the wait, as it controls the fate of endurance and is the sustenance of life. �I�m oxygen,� it says to the muscle, with more than a hint of superiority. �I can give you a lot of ATP, but you will have to wait for it.�

Since humans evolved for aerobic activities (Hochachka, Gunga & Kirsch 1998; Hochachka & Monge 2000), it�s not surprising that the aerobic system, which is dependent on oxygen, is the most complex of the three energy systems. The metabolic reactions that take place in the presence of oxygen are responsible for most of the cellular energy produced by the body. However, aerobic metabolism is the slowest way to resynthesize ATP. Oxygen, as the patriarch of metabolism, knows that it is worth the wait, as it controls the fate of endurance and is the sustenance of life. �I�m oxygen,� it says to the muscle, with more than a hint of superiority. �I can give you a lot of ATP, but you will have to wait for it.� Fat, which is stored as triglyceride in adipose tissue underneath the skin and within skeletal muscles (called�intramuscular triglyceride), is the other major fuel for the aerobic system, and is the largest store of energy in the body. When using fat, triglycerides are first broken down into free fatty acids and glycerol (a process called�lipolysis). The free fatty acids, which are composed of a long chain of carbon atoms, are transported to the muscle mitochondria, where the carbon atoms are used to produce acetyl-CoA (a process called�beta-oxidation).

Fat, which is stored as triglyceride in adipose tissue underneath the skin and within skeletal muscles (called�intramuscular triglyceride), is the other major fuel for the aerobic system, and is the largest store of energy in the body. When using fat, triglycerides are first broken down into free fatty acids and glycerol (a process called�lipolysis). The free fatty acids, which are composed of a long chain of carbon atoms, are transported to the muscle mitochondria, where the carbon atoms are used to produce acetyl-CoA (a process called�beta-oxidation).

Nutrition is increasingly recognized as a key component of optimal sporting performance, with both the science and practice of sports nutrition developing rapidly.1 Recent studies have found that a planned scientific nutritional strategy (consisting of fluid, carbohydrate, sodium, and caffeine) compared with a self-chosen nutritional strategy helped non-elite runners complete a marathon run faster2 and trained cyclists complete a time trial faster.3 Whereas training has the greatest potential to increase performance, it has been estimated that consumption of a carbohydrate�electrolyte drink or relatively low doses of caffeine may improve a 40 km cycling time trial performance by 32�42 and 55�84 seconds, respectively.4

Nutrition is increasingly recognized as a key component of optimal sporting performance, with both the science and practice of sports nutrition developing rapidly.1 Recent studies have found that a planned scientific nutritional strategy (consisting of fluid, carbohydrate, sodium, and caffeine) compared with a self-chosen nutritional strategy helped non-elite runners complete a marathon run faster2 and trained cyclists complete a time trial faster.3 Whereas training has the greatest potential to increase performance, it has been estimated that consumption of a carbohydrate�electrolyte drink or relatively low doses of caffeine may improve a 40 km cycling time trial performance by 32�42 and 55�84 seconds, respectively.4

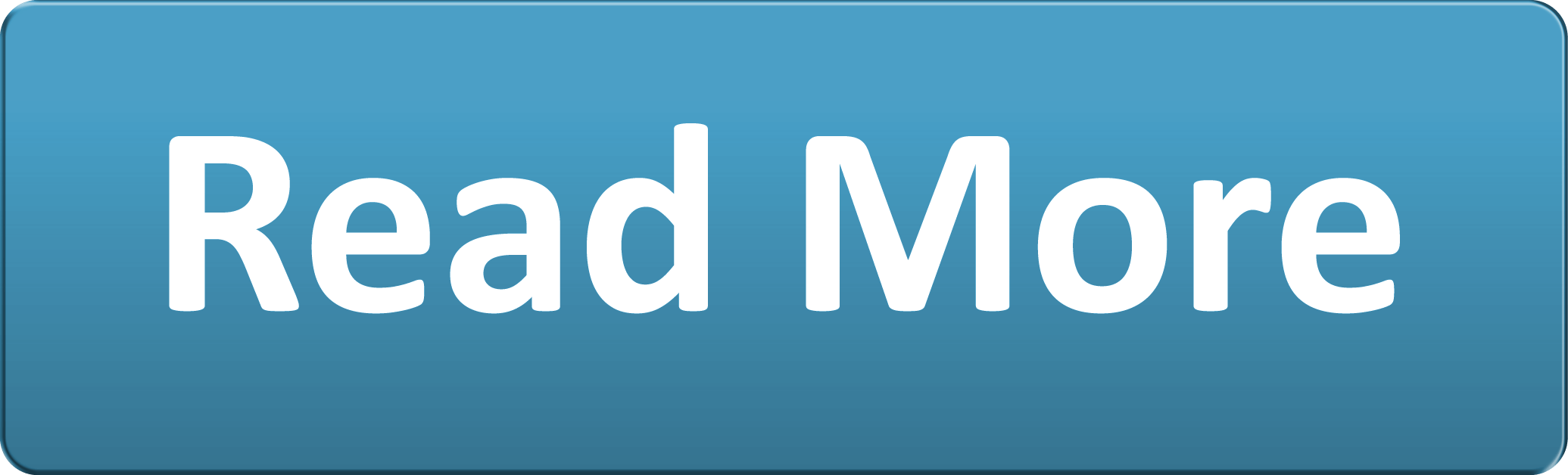

Carbohydrate ingestion has been shown to improve performance in events lasting approximately 1 hour.6 A growing body of evidence also demonstrates beneficial effects of a carbohydrate mouth rinse on performance.22 It is thought that receptors in the oral cavity signal to the central nervous system to positively modify motor output.23

Carbohydrate ingestion has been shown to improve performance in events lasting approximately 1 hour.6 A growing body of evidence also demonstrates beneficial effects of a carbohydrate mouth rinse on performance.22 It is thought that receptors in the oral cavity signal to the central nervous system to positively modify motor output.23

The �train-low, compete-high� concept is training with low carbohydrate availability to promote adaptations such as�enhanced activation of cell-signaling pathways, increased mitochondrial enzyme content and activity, enhanced lipid oxidation rates, and hence improved exercise capacity.26 However, there is no clear evidence that performance is improved with this approach.27 For example, when highly trained cyclists were separated into once-daily (train-high) or twice-daily (train-low) training sessions, increases in resting muscle glycogen content were seen in the low-carbohydrate- availability group, along with other selected training adaptations.28 However, performance in a 1-hour time trial after 3 weeks of training was no different between groups. Other research has produced similar results.29 Different strategies have been suggested (eg, training after an overnight fast, training twice per day, restricting carbohydrate during recovery),26 but further research is needed to establish optimal dietary periodization plans.27

The �train-low, compete-high� concept is training with low carbohydrate availability to promote adaptations such as�enhanced activation of cell-signaling pathways, increased mitochondrial enzyme content and activity, enhanced lipid oxidation rates, and hence improved exercise capacity.26 However, there is no clear evidence that performance is improved with this approach.27 For example, when highly trained cyclists were separated into once-daily (train-high) or twice-daily (train-low) training sessions, increases in resting muscle glycogen content were seen in the low-carbohydrate- availability group, along with other selected training adaptations.28 However, performance in a 1-hour time trial after 3 weeks of training was no different between groups. Other research has produced similar results.29 Different strategies have been suggested (eg, training after an overnight fast, training twice per day, restricting carbohydrate during recovery),26 but further research is needed to establish optimal dietary periodization plans.27 There has been a recent resurgence of interest in fat as a fuel, particularly for ultra endurance exercise. A high-carbohydrate strategy inhibits fat utilization during exercise,30 which may not be beneficial due to the abundance of energy stored in the body as fat. Creating an environment that optimizes fat oxidation potentially occurs when dietary carbohydrate is reduced to a level that promotes ketosis.31 However, this strategy may impair performance of high-intensity activity, by contributing to a reduction in pyruvate dehydrogenase activity and glycogenolysis. 32 The lack of performance benefits seen in studies investigating �high-fat� diets may be attributed to inadequate carbohydrate restriction and time for adaptation.31 Research into the performance effects of high fat diets continues.