by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Functional Medicine, Gastro Intestinal Health, Gut and Intestinal Health, Health, Nutrition, Wellness

Do you feel:

- A sense of fullness during and after meals?

- Do digestive problems subside with rest and relaxation?

- Diarrhea?

- Unpredictable abdominal swelling?

- Frequent bloating and distention after eating?

If you are experiencing any of these situations, then you might be experiencing problems with your digestive tract. Here are some ways to improve your digestion problems naturally.

Different factors can impact a person’s digestion and overall gut health. There are things that people have control like how much sleep they are getting while the other things that are not in a person’s control like genetics and family history. If a person is experiencing stomach problems, then it might be the poor lifestyle choices that may be hurting their gut. Having a well-balanced diet and regularly exercising is good, but those are just two of the many ways to regulate digestive health.

Here are some of the lifestyles that may negatively impact the body�s gut health:

- What a person is eating

- Mindful of mindless eating

- Exercise routine

- Daily hydration

- Sleep schedule

- Stress and anxiety levels

- Prescription and over the counter medications a person takes

- Bad habits like late-night eating or excessive alcohol or tobacco use

These factors can do bodily harm and can cause the development of chronic illnesses.

11 Ways To Improve Digestive Health

Even though these factors can negatively affect a person�s digestion tract and overall gut health, there are 11 ways to help improve the digestive tract naturally and be beneficial to not only the gut but to the body.

Eating More Colorful, Plant-based and Fiber-Rich Foods

Even though digestive issues can be challenging, avoiding certain foods and eating more plant-based and fiber-rich foods can help ease those uncomfortable symptoms. Quality nut and seeds, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes can protect against a lot of digestive disorders and promote a regular bowel movement. To avoid discomfort on the digestive tract, try avoiding certain foods that are tough on the stomach like fried, artificially processed, or acidic foods.

If a person is suffering from an upset stomach or been diagnosed with IBS (irritable bowel syndrome), they might want to consider adopting an anti-inflammatory rich diet to prevent inflammation in the gut.

Consider Meal Frequency and Sizing

When a person continually snacking or tend to have three big meals a day is known as a grazer. Grazing food may not be suitable for people due to being prone to constipation. These habits can impact the person’s digestive health, and recent clinical studies have been shown that intermittent fasting can be beneficial to gut health and the whole body.

Practicing Mindful Eating

Sometimes overeating and eating too quickly can often lead to unpleasant indigestion symptoms such as gas and bloating. Thankfully there is an inclusive practice known as mindful eating, and it has been studied to a practical approach to reducing indigestion in the gut. Research has shown that mindful eating can reduce symptoms of IBS and ulcerative colitis.

To practice eating mindfully, keep in mind the following:

- Turning off the tv and putting away the phones at mealtimes.

- Taking a moment and inhale after sitting down with the plate in front of the individual. Take notice of how it smells.

- You are taking in on how the food looks on the plate.

- Select each bite of consciously.

- Chew the bites of food slowly.

- Eat slowly.

- Take breaks, sip water, or have a quick chat in between each bite.

- Take in the taste, texture, and temperature of every bite.

- Take time to relax after finishing a meal.

Following these tricks and taking the time to relax and paying attention to the body before a meal may improve digestive symptoms such as indigestion and bloating.

Exercise Regularly

Exercise can help digestion. When people move their bodies on a day to day basis can affect their digestion. Since it is mostly due to its anti-inflammatory effects, exercise can have a very positive impact on the digestive system. Studies have shown that living a sedentary lifestyle can be damaging to the gut. Working out can help a person relieve their stress, enable them to maintain a healthy weight, strengthen abdominal muscles, and stimulate food to move through the large intestines.

According to research, aerobic exercises, like dancing or high interval workout classes, are particularly great by increasing the blood flow to the GI tract. Keep in mind that it is best to avoid this type of high impact exercise right after eating. If an individual has a sensitive stomach, resting for 30 minutes in between workouts and meals is the best option.

Staying Hydrated

Not drinking enough water is a common cause of constipation among adults and children, since lots of people often replace water with sugary alternatives. Studies have shown that people should aim to drink at least 1.5 to 2 liters of non-caffeinated beverages daily to prevent constipation, and if they exercise, they should be drinking more water.

They can also increase their water intake by eating fruits that have high water content, drinking herbal teas, and non-caffeinated beverages like flavored seltzer waters.

Trying to Get A Good Night Sleep

Not getting enough hours to sleep and poor quality sleep has been associated with several gastrointestinal diseases. Studies show that people who are sleep deprived are most likely to suffer from stomach pains, diarrhea, upset stomach, or even suffer from inflammatory bowel disease. So people need to get quality sleep as the main priority.

Practice Ways to Manage Stress

Stress can affect a person�s digestion and the gastrointestinal tract big time. When an individual is chronically stressed out, their body is continuously in a flight or fight mode. Being chronically stressed out can lead to several unpleasant digestive symptoms such as constipation, diarrhea, bloating, IBS, and stomach ulcers.

There are ways to relieve stress through stress management techniques like yoga, acupuncture, cognitive behavioral therapy, and meditation. Research shows that these techniques have been shown to improve symptoms in people with IBS drastically. Even taking the time to sit quietly and practicing breathing exercises for five minutes can help alleviate stress levels.

Cutting Back on Drinking Alcohol

Many individuals experience diarrhea and several other unpleasant symptoms after consuming alcohol. This is because alcohol can trigger some severe changes in the digestive system. Studies have mentioned that when the gastrointestinal tract comes in contact with alcohol, it becomes inflamed. This is because the intestines do not absorb water as efficiently, causing the overall digestion to speed up, and the good/harmful bacteria balance is thrown off.

Stop Smoking

Smoking can impact the entire body, including the gut. Studies have shown that smoking, chewing, and vaping tobacco has been linked to several common disorders in the digestive system, such as heartburn, peptic ulcers, and GERD (gastroesophageal reflux disease). Smoking can also worsen gastrointestinal symptoms in other conditions like Crohn’s disease. When a person quits smoking, it can quickly reverse some of the effects of smoking on the digestive system and can keep the symptom of some gastrointestinal diseases from becoming worse.

Consider Taking Supplements

Taking dietary supplements is a great way to make sure that the body is getting the nutrients it needs for proper digestion.

- Probiotics are excellent digestive supplements to alleviate and improve symptoms of gas, to bloat, and stomach pains for people with IBS.

- Glutamine is an amino acid that supports gut health. Studies show that glutamine can reduce leaky gut in people who are sick.

- Zinc is a mineral that is essential for a healthy gut. When a person has a deficiency in zinc, it can lead to a variety of unpleasant digestive disorders. So taking zinc supplements can be beneficial to reducing digestive problems.

Be Aware of Medication Interactions and Their Side Effects

The medication that a person is taking can cause stomach discomfort and make them prone to diarrhea or constipation. Conventional medication such as aspirin and other pain medicine have been studied to upset the lining of the stomach, causing damage to the intestinal permeability.

Conclusion

Practicing these 11 ways can be beneficial and provide improvement to a person’s digestive tract. When disruptive factors disrupt the digestive tract, it can lead the body to have inflammation, leaky gut, and digestive problems. Some products are specialized to support the gastrointestinal tract and provide support to the body’s metabolism to make sure the body is functioning correctly.

The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal, and nervous health issues or functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions. We use functional health protocols to treat injuries or disorders of the musculoskeletal system. Our office has made a reasonable attempt to provide supportive citations and has identified the relevant research study or studies supporting our posts. We also make copies of supporting research studies available to the board and or the public upon request. To further discuss the subject matter above, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900.

References:

Ali, Tauseef, et al. �Sleep, Immunity and Inflammation in Gastrointestinal Disorders.� World Journal of Gastroenterology, Baishideng Publishing Group Co., Limited, 28 Dec. 2013, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3882397/.

Bilski, Jan, et al. �Can Exercise Affect the Course of Inflammatory Bowel Disease? Experimental and Clinical Evidence.� Pharmacological Reports: PR, US National Library of Medicine, Aug. 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27255494.

Bischoff, Stephan C. �’Gut Health’: a New Objective in Medicine?� BMC Medicine, BioMed Central, 14 Mar. 2011, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3065426/.

Catterson, James H, et al. �Short-Term, Intermittent Fasting Induces Long-Lasting Gut Health and TOR-Independent Lifespan Extension.� Current Biology: CB, Cell Press, 4 June, 2018, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5988561/.

Chiba, Mitsuro, et al. �Recommendation of Plant-Based Diets for Inflammatory Bowel Disease.� Translational Pediatrics, AME Publishing Company, Jan. 2019, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6382506/.

Didari, Tina, et al. �Effectiveness of Probiotics in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Updated Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis.� World Journal of Gastroenterology, Baishideng Publishing Group Inc, 14 Mar. 2015, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25780308.

Konturek, Peter C, et al. “Stress and the Gut: Pathophysiology, Clinical Consequences, Diagnostic Approach, and Treatment Options.” Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology: an Official Journal of the Polish Physiological Society, US National Library of Medicine, Dec. 2011, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22314561.

Kristeller, Jean L, and Kevin D Jordan. �Mindful Eating: Connecting With the Wise Self, the Spiritual Self.� Frontiers in Psychology, Frontiers Media SA, 14 Aug. 2018, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6102380/.

Lakatos, Peter Laszlo. �Environmental Factors Affecting Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Have We Made Progress?� Digestive Diseases (Basel, Switzerland), US National Library of Medicine, 2009, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19786744.

Miller, Carla K, et al. �Comparative Effectiveness of a Mindful Eating Intervention to a Diabetes Self-Management Intervention among Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: a Pilot Study.� Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, US National Library of Medicine, Nov. 2012, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3485681/.

Mottaghi, Azadeh, et al. �Efficacy of Glutamine-Enriched Enteral Feeding Formulae in Critically Ill Patients: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials.� Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition, US National Library of Medicine, 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27440684.

Oettl�, G J. �Effect of Moderate Exercise on Bowel Habit.� Gut, US National Library of Medicine, Aug. 1991, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1885077.

Philpott, HL, et al. “Drug-Induced Gastrointestinal Disorders.” Frontline Gastroenterology, BMJ Publishing Group, Jan. 2014, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5369702/.

Popkin, Barry M, et al. �Water, Hydration, and Health.� Nutrition Reviews, US National Library of Medicine, Aug. 2010, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2908954/.

Qin, Hong-Yan, et al. �Impact of Psychological Stress on Irritable Bowel Syndrome.� World Journal of Gastroenterology, Baishideng Publishing Group Inc, 21 Oct. 2014, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4202343/.

Skrovanek, Sonja, et al. �Zinc and Gastrointestinal Disease.� World Journal of Gastrointestinal Pathophysiology, Baishideng Publishing Group Inc, 15 Nov. 2014, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25400994.

Unknown, Unknown. �11 Ways To Improve Digestion Problems Naturally.� Fullscript, 9 Sept. 2019, fullscript.com/blog/lifestyle-tips-for-digestive-health.

Unknown, Unknown. �Smoking and the Digestive System.� National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1 Sept. 2013, www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/smoking-digestive-system.

Wong, Ming-Wun, et al. �Impact of Vegan Diets on Gut Microbiota: An Update on the Clinical Implications.� Ci Ji Yi Xue Za Zhi = Tzu-Chi Medical Journal, Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd, 2018, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6172896/.

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Functional Medicine, Gastro Intestinal Health, Gut and Intestinal Health, Health, Wellness

Do you feel:

- That eating relieves fatigue?

- Hormone imbalances?

- Aches, pains, and swelling throughout the body?

- Bodily swelling for no reason?

- Inflammation on your body?

If you are experiencing any of these situations, you might be experiencing inflammation, and it might affect your endocrine system.

Inflammation and the Endocrine System

Inflammation is a defense mechanism in the body. The immune system can recognize the damaged cells, irritants, and pathogens that cause harm to the body and began the healing process. When the inflammation turns into chronic inflammation, it can cause several diseases and conditions in the body and can cause harm to an individual.

Inflammation can cause dysfunction when it is in the endocrine system. The endocrine system is a series of glands that produce and secretes hormones that the body needs and uses for a wide range of functions. When the endocrine glands produce hormones, they are sent into the bloodstream to the various tissues in the body. Once they are in the various tissues, the hormone signals the tissues to tell them what they are supposed to do. When the glands do not produce the right amount of hormones, various diseases like inflammation can affect the body.

Inflammation Symptoms and Causes

Two questions are asked concerning the interaction of the endocrine system with inflammation: How does inflammation influences the endocrine system, and does it influences disease? How do hormones influence inflammation and immune cells? A theory had integrated both questions and has recently been demonstrated in the context of chronic inflammation considering a rheumatic disease.

So how does inflammation influence the endocrine system? Inflammation symptoms can vary depending on if it is acute or chronic. The effects of acute inflammation are summed up by the acronym PRISH. They include:

- Pain: The inflamed area is most likely to be painful, especially during and after touching. The chemicals that stimulate the nerve endings are released, making the area more sensitive.

- Redness: This occurs due to the capillaries in the area that is filled with more blood than usual.

- Immobility: There may be some loss of function in the region of the inflammation where the injury has occurred.

- Swelling: A buildup of fluid causes this.

- Heat: Heat is caused by having more blood flow to the affected area and making it warm to the touch.

These acute inflammation signs only apply to an inflammation on the skin. If the inflammation occurs deep inside the body, like the endocrine system and the internal organs, some of the signs may be noticeable. Some internal organs may not have sensory nerve endings nearby; for example, they will not have pain.

With the effects of chronic inflammation, it is long term and can last for several months or even years. The results from chronic inflammation can be from:

- An autoimmune disorder that attacks normal healthy tissue and mistaking it for a pathogen that causes diseases like fibromyalgia.

- An industrial chemical that is exposed to a low level of a particular irritant over a long period.

- Failure to eliminate whatever was causing acute inflammation.

Some of the symptoms of chronic inflammation can be present in different ways. These can include:

- Fatigue

- Mouth sores

- Chest pains

- Abdominal pain

- Fever

- Rash

- Joint pain

When inflammation affects the endocrine system, it can cause the body’s system to be unbalanced, and it can lead to chronic long term illnesses.

With the second question, it is asking how do hormones influence inflammation and the immune system? When the hormone levels are either too high or too low, it can have several effects on a person’s health. The signs and symptoms can depend on hormones that are out of balance.

Inflammation and Hormones

Research has shown that some of the conditions that are affecting the endocrine system can lead to autoimmune disorders. High levels of hormones can lead to hyperthyroidism, Cushing syndrome, and Graves disease. While low levels of hormones can lead to hypothyroidism and Addison disease. When the levels of the hormones are either too high or too low, the body fluctuates from either weight gain or weight loss and disrupting the glucose levels. This can cause a person to get diabetes and obesity.

Obesity is the main risk factor for type 2 diabetes. During the development of obesity, subclinical inflammatory activity in the tissues are activated and involves the metabolism and energy homeostasis. In the body, intracellular serine/threonine kinases are activated in response to those inflammatory factors. They can catalyze the inhibitory phosphorylation of the key proteins of the insulin-signaling pathway, leading to insulin resistance in the body.

Studies have shown that inflammation is a general tissue response to a wide variety of stimuli. When inflammation is not adequately regulated, inflammatory responses may be exaggerated or ineffective, which can lead to immune dysfunction, recurring infections, and tissue damage, both locally and systemically. With various hormones, cytokines, vitamins, metabolites, and neurotransmitters being key meditators of the immune and inflammatory responses to the endocrine system.

Another study shows that aging, chronic psychological stress, and mental illnesses are also accompanied by chronic smoldering inflammation. Chronic smoldering inflammation in humans is already established with elevations of serum levels, leading to an increase in resting metabolic rate.

Conclusion

So inflammation is a double edge sword where it can heal the body but also cause the body harm if it is deep into the internal organs and body systems. With the endocrine system, the levels of the hormones can fluctuate from going too high or too low and affecting the tissues in the body, causing inflammation. �When an individual is suffering from chronic inflammation, it can change their lifestyle drastically. Some products are here to help counter the metabolic effects of temporary stress and make sure that the endocrine system is supported as well.

The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal, and nervous health issues or functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions. We use functional health protocols to treat injuries or disorders of the musculoskeletal system. Our office has made a reasonable attempt to provide supportive citations and has identified the relevant research study or studies supporting our posts. We also make copies of supporting research studies available to the board and or the public upon request. To further discuss the subject matter above, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900.

References:

Coope, Andressa, et al. �MECHANISMS IN ENDOCRINOLOGY: Metabolic and Inflammatory Pathways on the Pathogenesis of Type 2 Diabetes.� European Journal of Endocrinology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, May 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26646937.

Felman, Adam. �Inflammation: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment.� Medical News Today, MediLexicon International, 24 Nov. 2017, www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/248423.php.

Salazar, Luis A., et al. �The Role of Endocrine System in the Inflammatory Process.� Mediators of Inflammation, Hindawi, 29 Sept. 2016, www.hindawi.com/journals/mi/2016/6081752/.

Seladi-Schulman, Jill. �Endocrine System Overview.� Healthline, 22 Apr. 2019, www.healthline.com/health/the-endocrine-system.

Straub, Rainer H. �Interaction of the Endocrine System with Inflammation: a Function of Energy and Volume Regulation.� Arthritis Research & Therapy, BioMed Central, 13 Feb. 2014, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3978663/.

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Functional Medicine, Gastro Intestinal Health, Gut and Intestinal Health, Health, Nutrition, Wellness

Do you feel:

- Inflammation on your joints or all over the body?

- Stomach pain, burning, or aching 1-4 hours after eating?

- Unpredictable abdominal pain?

- Gas immediately following after a meal?

- Excessive belching, burping, or bloating?

If you are experiencing any of these situations, then try these top ten superfoods to prevent inflammation in your body.

Superfoods lack any formal criteria, and people wonder what makes a food a superfood. Medical experts agreed that foods with the title “superfood” have health benefits that go far beyond what is listed on their nutrition labels. There is a wide range of health-promoting superfoods that can be incorporated into a person’s diet in several different ways. Eating superfood alone will not make anyone healthier overnight, but adding them to an already balanced diet can give anyone a mega-dose of added health benefits to their body.

Getting to Know Superfoods

According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, a superfood is defined as “a food that rich in compounds and considered beneficial to a person’s health. It can be any foods that have antioxidants, fatty acids, or fibers in their nutrient compounds. While the Oxford Dictionary defines a superfood as �a nutrient-rich food that is considered to be especially beneficial for health and well-being.�

Here are the top ten superfoods that have been scientifically proven to help optimize the body’s ability to function correctly. These superfoods are not only super healthy, but they are affordable and readily available in the grocery stores, online, and at farmer’s markets.

A�ai Berries

A�ai berries are high in antioxidants. They also contain B vitamins, magnesium, potassium, healthy fats, and phosphorus. The a�ai berry is one of the most well-known superfoods that is beneficial for the body’s microbiome. Studies have shown that a�ai berries have anti-inflammatory properties, help improve the cognitive function, maintaining healthy blood sugar levels, and protect against heart diseases. The berries themselves have also been suggested to help slow down age-related memory loss in individuals.

Studies have shown that the health benefits of the a�ai berries are that the berries contain a range of polyphenols that protects cellular oxidative damage in vitro and can provide ant-inflammatory signaling in the body by reducing the production of free radicals by inflammatory cells. Chronic inflammation in the body can lead to diseases like fibromyalgia. So consuming this berry can help lower the risk of inflammation in the body.

Plant-based protein

Plant proteins are abundant, branched-chain containing essential amino acids, and are exceptionally high in lysine. Research has been shown that lysine can help balance blood glucose in the body. Lysine even can increase muscle strength and combat anxiety in the body.

Plant-based proteins that contain carotenoids and flavonoids can modulate inflammatory responses in the body as well as the immunological process as well. Plant foods have anti-inflammatory potential that everyone needs in their diet to reduce inflammatory responses that is in the body.

Salmon

Salmon is a superfood that has one of the highest sources for omega-3 fatty acids. Omega-3 fatty acids have been shown to lower the risk of developing coronary heart diseases, lowers metabolic syndrome, and diabetes. Studies have been shown that fish oil has also been known to help combat late-onset Alzheimer�s disease.

Consuming salmon or any foods that contain omega-3s may help alleviate oxidative stress that the body may have picked up. Omega-3s even play a role in lowering the risk of inflammation on individuals who have to develop fibromyalgia. Since it associates with pro-inflammatory cytokines, eating omega-3 fatty foods can help lower the inflammation and alleviate it as well.

Avocados

Avocados are a nutrient-rich superfood, high fiber fruits that play a significant role in combating chronic diseases in the body. Eating avocados regularly have been known to lower the risk of heart disease, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and certain cancers.

Since avocados are a nutrient-dense source of MUFA (monounsaturated fatty acids), the fruit can be used to replace SFA (saturated fatty acids) in a diet to lower LDL-C (low-density lipoprotein cholesterol) in the body.

Kale

Kale has an excellent source of nutrients like zinc, folate, magnesium, calcium, vitamin C, fiber, and iron. Research has shown that dark leafy greens can reduce the risk of chronic illnesses like type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

Olive oil

Olive oil is a superfood that has been shown to provide a range of various health benefits. Extra virgin olive oil is associated with reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality on individuals that have a high cardiovascular risk.

Olive oil has a monounsaturated fat called oleic acid, which helps reduce inflammation in the body.

Sweet potato

Sweet potato is the superfood root vegetable that is full of nutrients that are beneficial to the body. They are an excellent source of carotenoids, fiber, potassium, vitamin C, and vitamin A.

Consuming sweet potato is beneficial for the body due to reducing the risk of inflammation and DNA damage. Since it contains high levels of antioxidants, it may also prevent cell damage as well in the body.

Fermented Foods

Fermented foods like yogurt, kefir sauerkraut, and many others are heavily sought after superfoods by consumers. This is because fermented foods have a range of fantastic health benefits like antioxidants, anti-microbial, anti-fungal, anti-inflammatory, andante-diabetic properties.

Green tea

Green tea is a lightly caffeinated beverage that has a broad spectrum of health benefits for the body. It is rich with antioxidants and polyphenolic compounds that can protect the body against chronic diseases and be a useful tool for bodyweight management.

Seaweed

Seaweed is packed with several nutrients like folate, vitamin K iodine, and fiber that is beneficial for the body. It plays an essential role by helping lowering blood pressure and to treat several chronic illnesses. Studies have shown that due to their potential beneficial activities such as anti-inflammatory and anti-diabetic effects that are beneficial to prevent flare-ups in the white adipose tissue and systemic IR.

Conclusion

Superfoods are an essential additive boost to any healthy diet. These ten superfoods contain anti-inflammatory properties that are beneficial to the body to prevent the risk of inflammation in the body. Eating these foods combine with these products will provide relief from oxidative stress and inflammation that the body may encounter, as well as providing support to the endocrine system.

The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal, and nervous health issues as well as functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions. We use functional health protocols to treat injuries or chronic disorders of the musculoskeletal system. To further discuss the subject matter above, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez or contact us at�915-850-0900�.

References:

Basu, Arpita, et al. �Dietary Factors That Promote or Retard Inflammation.� Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, May 2006, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16484595.

Dellwo, Adrienne. �The Potential Benefits of Omega-3 for Fibromyalgia & CFS.� Verywell Health, Verywell Health, 7 July 2019, www.verywellhealth.com/omega-3-for-fibromyalgia-and-chronic-fatigue-syndrome-715987.

Felman, Adam. �Fibromyalgia: Symptoms, Causes, and Treatment.� Medical News Today, MediLexicon International, 5 Jan. 2018, www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/147083.php.

Jensen, Gitte S, et al. �Pain Reduction and Improvement in Range of Motion after Daily Consumption of an A�ai (Euterpe Oleracea Mart.) Pulp-Fortified Polyphenolic-Rich Fruit and Berry Juice Blend.� Journal of Medicinal Food, Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., 2011, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3133683/.

Oh, Ji-Hyun, et al. �Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Diabetic Effects of Brown Seaweeds in High-Fat Diet-Induced Obese Mice.� Nutrition Research and Practice, The Korean Nutrition Society and the Korean Society of Community Nutrition, Feb. 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4742310/.

Smriga, Miro, et al. �Lysine Fortification Reduces Anxiety and Lessens Stress in Family Members in Economically Weak Communities in Northwest Syria.� Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, National Academy of Sciences, 1 June 2004, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15159538.

Tanaka, Takuji, et al. �Cancer Chemoprevention by Carotenoids.� Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), MDPI, 14 Mar. 2012, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22418926.

Unknown, Unknown. �What Are Superfoods? Top 10 Superfoods.� Fullscript, 4 Mar. 2019, fullscript.com/blog/superfoods.

Unni, Uma S, et al. �The Effect of a Controlled 8-Week Metabolic Ward Based Lysine Supplementation on Muscle Function, Insulin Sensitivity and Leucine Kinetics in Young Men.� Clinical Nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland), U.S. National Library of Medicine, Dec. 2012, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22524975.

Wang, Li, et al. �Effect of a Moderate Fat Diet with and without Avocados on Lipoprotein Particle Number, Size and Subclasses in Overweight and Obese Adults: a Randomized, Controlled Trial.� Journal of the American Heart Association, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 7 Jan. 2015, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25567051.

Wang, Ping-Yu, et al. �Higher Intake of Fruits, Vegetables or Their Fiber Reduces the Risk of Type�2 Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis.� Journal of Diabetes Investigation, John Wiley and Sons Inc., Jan. 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26816602.

Watzl, Bernhard. �Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Plant-Based Foods and of Their Constituents.� International Journal for Vitamin and Nutrition Research. Internationale Zeitschrift Fur Vitamin- Und Ernahrungsforschung. Journal International De Vitaminologie Et De Nutrition, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Dec. 2008, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19685439.

?anlier, Nevin, et al. �Health Benefits of Fermented Foods.� Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2019, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28945458.

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Anti Aging, Gastro Intestinal Health, Gut and Intestinal Health, Health, Nutrition, Wellness

Do you feel:

- Like you have been diagnosed with Celiac Disease, Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Diverticulosis/Diverticulitis, or Leaky Gut Syndrome?

- Excessive belching, burping, or bloating?

- Abnormal distention after certain probiotics or natural supplements?

- Suspicion of nutritional malabsorption?

- Do digestive problems subside with relaxation?

If you are experiencing any of these situations, then you might be experiencing gut problems and might have to try the 4R Program.

Food sensitivities, rheumatoid arthritis, and anxiety have been associated with impaired gastrointestinal permeability. These various conditions can happen from many factors that can impact the digestive tract. If left untreated it can potentially be the result of dysfunction of the intestinal permeability barrier, causing inflammation, and severe health conditions that the gut can develop. The 4R program is used to restore a healthy gut in the body and involves four steps. They are: remove, replace, reinoculated, and repair.

Intestinal Permeability

The intestinal permeability helps protects the body and makes sure that harmful bacteria do not enter the gut. It protects the body from potential environmental factors that can be harmful and are entering through the digestive tract. It can be either toxin, pathogenic microorganisms, and other antigens that can harm the digestive tract causing problems. The intestinal lining is consisting of a layer of epithelial cells that are separated by tight junctions. In a healthy gut, the tight junction regulates the intestinal permeability by selectively allowing substances to enter and travel across the intestinal barrier and preventing harmful factors from being absorbed.

Certain environmental factors can damage the tight junction, and the result is that it can increase the intestinal permeability, which causes intestinal hyperpermeability or leaky gut in the body. Contributing factors can increase intestinal permeability like an excessive amount of saturated fats and alcohol, deficiencies in nutrients, chronic stress, and infectious diseases.

With an increased intestinal permeability in the gut, it can enable antigens to cross the gut mucosa and enter the bloodstream causing an immune response and inflammation to the body. There are certain gastrointestinal conditions that are associated with intestinal hyperpermeability and if left untreated it can trigger certain autoimmune conditions that can cause harm to the body.

4Rs Program

The 4Rs is a program that healthcare professionals advise their patients to use when they are addressing disruptive digestive issues and help support gut healing.

Removing the Problem

The first step in the 4Rs program is to remove harmful pathogens and inflammation triggers that are associated with increased intestinal permeability. Triggers like stress and chronic alcohol consumption can do much harm to an individual’s body. So targeting these harmful factors from the body is to treat it with medication, antibiotics, supplements, and the removal of inflammatory foods from the diet is advised, including:

- – Alcohol

- – Gluten

- – Food additives

- – Starches

- – Certain fatty acids

- – Certain foods that a person is sensitive to

Replacing the Nutrients

The second step of the 4Rs program is to replace the nutrients that are causing the gut problems through inflammation. Certain nutrients can help reducing inflammation in the gut while making sure that the digestive tract is being supported. There are some anti-inflammatory foods that are nutritious. These include:

- – High-fiber foods

- – Omega-3s

- – Olive oil

- – Mushrooms

- – Anti-inflammatory herbs

There are certain supplements can be used to support digestive function by assisting and absorbing the nutrients to promote a healthy gut. What the digestive enzymes do is that they assist in helping to break down fats, proteins, and carbohydrates in the gut. This will help benefit individuals that have an impaired digestive tract, food intolerances, or having celiac disease. Supplements like bile acid supplements can help assist in nutrient absorption by merging lipids together. Studies have stated that bile acids have been used to treat the liver, gallbladder, and bile duct while preventing gallstone formation after bariatric surgery.

Reinoculated The Gut

The third step is of the 4rs program to reinoculated the gut microbe with beneficial bacteria to promote a healthy gut function. Studies have been shown that probiotic supplements have been used to improve the gut by restoring beneficial bacteria. With these supplements, they provide the gut an enhancement by secreting anti-inflammatory substances into the body, help support the immune system, altering the body’s microbial composition, and reducing the intestinal permeability in the gut system.

Since probiotics are found in fermented foods and are considered as a transient since they are not persistent in the gastrointestinal tract and are beneficial. Surprisingly, they still have an impact on human health due to influencing the gut by producing vitamins and anti-microbial compounds, thus providing diversity and gut function.

Repairing the Gut

The last step of the 4Rs program is to repair the gut. This step involves repairing the intestinal lining of the gut with specific nutrients and herbs. These herbs and supplements can help decrease intestinal permeability and inflammation in the body. Some of these herbs and supplements include:

- – Aloe vera

- – Chios mastic gum

- – DGL (Deglycyrrhizinated licorice)

- – Marshmallow root

- – L-glutamine

- – Omega-3s

- � Polyphenols

- – Vitamin D

- – Zinc

Conclusion

Since many factors can adversely affect the digestive system in a harmful way and can be the contributor to several health conditions. The main goal of the 4Rs program is to minimize these factors that are harming the gut and reducing inflammation and increased intestinal permeability. When the patient is being introduced to the beneficial factors that the 4Rs provide, it can lead to a healthy, healed gut. Some products are here to help support the gastrointestinal system by supporting the intestines, improving the sugar metabolism, and targeting the amino acids that are intended to support the intestines.

The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal, and nervous health issues or functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions. We use functional health protocols to treat injuries or disorders of the musculoskeletal system. Our office has made a reasonable attempt to provide supportive citations and has identified the relevant research study or studies supporting our posts. We also make copies of supporting research studies available to the board and or the public upon request. To further discuss the subject matter above, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900.

References:

De Santis, Stefania, et al. �Nutritional Keys for Intestinal Barrier Modulation.� Frontiers in Immunology, Frontiers Media S.A., 7 Dec. 2015, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4670985/.

Ianiro, Gianluca, et al. �Digestive Enzyme Supplementation in Gastrointestinal Diseases.� Current Drug Metabolism, Bentham Science Publishers, 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4923703/.

Mu, Qinghui, et al. �Leaky Gut As a Danger Signal for Autoimmune Diseases.� Frontiers, Frontiers, 5 May 2017, www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2017.00598/full.

Rezac, Shannon, et al. �Fermented Foods as a Dietary Source of Live Organisms.� Frontiers in Microbiology, Frontiers Media S.A., 24 Aug. 2018, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6117398/.

Sander, Guy R., et al. �Rapid Disruption of Intestinal Barrier Function by Gliadin Involves Altered Expression of Apical Junctional Proteins.� FEBS Press, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 8 Aug. 2005, febs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1016/j.febslet.2005.07.066.

Sartor, R Balfour. �Therapeutic Manipulation of the Enteric Microflora in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Antibiotics, Probiotics, and Prebiotics.� Gastroenterology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, May 2004, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15168372.

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Functional Medicine, Gastro Intestinal Health, Gut and Intestinal Health, Health, Wellness

Do you have:

- Itchy watery eyes?

- Unexplained itchy skin?

- Aches, pains, and swelling throughout the body?

- Unpredictable food reaction?

- Redden skin, especially in the palms?

If you are suffering from any of these symptoms, then you might be experiencing an allergy attack in your body.

The Rise of Allergies

The rise of allergies has not gone unnoticed amongst the young and the old. The allergy disease has affected over 30% of individuals in many communities, particularly young children, have underscored the need for effective prevention strategies in their early lives. Some individuals will blame the increase in toxin exposure while others blame the food, but mostly everyone will admit that the answers to how the allergy disease comes from are still unclear. Whether it be food, environmental factors, or skin allergies, the common denominator that causes the allergies to develop is in the immune system, especially in its inflammatory department.

The body�s immune system is linked to the entire body microbiome, and it also resides in the gastrointestinal tract. It has been said that the health and function of the immune system are directly associated with the diversity as well as the health of the microbiome. So it is reasonable to consider the microbiome when healthcare professionals are seeking to solve the allergy enigma.

Types of Allergic Reactions

With most allergy reactions, they are manifested in either the gastrointestinal tract, respiratory tract, or the skin. It is not a surprise that these organ systems are also where the body’s microbiome is the most heavily concentrated. A variety of bacterial species make their homes in these organ systems since these three organ systems represent the primary portals of entry for these pathogens.

It is logically that the microbiome of the body is so heavily concentrated as it functions as the first line of defense against invading pathogens and antigens. When there is a weak microbiome, or it lacks biodiversity, it will become a weak defense system, and the immune system is required to “pick up the slack” by identifying and protecting the body against these foreign invaders, which includes the common allergens that a person can get.

Skin Allergies

Skin allergies are where the skin becomes red, bumpy, and itchy rashes to become irritating, painful, and embarrassing for some people. Rashes can be caused by many factors, including exposure to certain plants, an allergic reaction to specific medication or food, or by illnesses like measles or chickenpox. Eczema, hives, and contact dermatitis are the three types of skin rashes. Eczema and hives are the two most common types of skin rashes and are related to allergies.

- Eczema: Also known as atopic dermatitis, can affect between 10 to 20 percent of children and 1 to 3 percent of adults. People with eczema will experience dry, red, irritated, and itchy skin. When it is infected, the skin may have small fluid-filled bumps that can ooze clear or yellowish liquid. Anyone with eczema can often have a family history of allergies.

- Hives: Also known as urticaria, this skin rash is raised, red bumps or welts that appear on the body. Hives can cause two conditions, and they are acute urticaria and chronic urticaria. Acute urticaria is most commonly caused by exposure to an allergen or by an infection, while the causes of chronic urticaria are still mostly unknown.

- Contact dermatitis: This skin rash is a reaction that appears when the skin comes in contact with an irritant or an allergen. Soaps, laundry products, shampoos, Excessive exposure to water, or the sun are some of the factors that can cause contact dermatitis. The symptoms can include rashes, blisters, itching, and burning.

Food Allergies

Anyone with a food allergy has an immune system that reacts to specific proteins found in food. Their immune system starts attacking these compounds as if they were harmful pathogens like a bacterium or a virus. Food allergies can affect 250 million to 550 million people in developed and developing countries.

The symptoms can range from mild to severe and can affect individuals differently. The most common signs and symptoms of an individual’s experience include:

- The skin may become itchy or blotchy

- Lips and face might swell

- Tingling in the mouth

- Burning sensation on the lips and mouth

- Wheezing

- Runny nose

Studies have found out that many people who think they have a food allergy may have a food intolerance. These two are entirely different because food intolerances do not involve the IgE antibodies, and the symptoms may be immediate, delayed, or similar to food allergies. Food intolerances occur due to proteins, chemicals, and other factors that can compromise the intestinal permeability. While food allergies mean that even a small amount of food is going to trigger the immune system, causing an allergic reaction.

Seasonal Allergies

Seasonal allergies are one of the most common allergic reactions that people get. About 8 percent of Americans experience it, according to the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, and it is commonly known as hay fever. Hay fever occurs when the immune system overreacts to outdoor allergens like pollen, weeds, cut grasses, and wind-pollinated plants.� Seasonal allergies are less common in the winter; however, it is possible to experience allergic rhinitis year-round, depending on where the individual lives and on the allergy triggers they may have.

Symptoms of seasonal allergies can range from mild to severe, including:

- Sneezing

- Runny or stuffy nose

- Water and itchy eyes

- Itchy throat

- Ear congestion

- Postnasal drainage

Conclusion

Allergies are a disease that attacks the immune system and can be triggered by many factors, whether it be from food, environmental factors, or the toxins that a person is exposed to. There are ways to lower the allergy symptoms through medicine or foods that have prebiotics and probiotic nutrients that can reduce the reactions. Some products can help support the immune system and can offer nutrients to the gastrointestinal tract and metabolic support.

The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal, and nervous health issues as well as functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions. We use functional health protocols to treat injuries or chronic disorders of the musculoskeletal system. To further discuss the subject matter above, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

References:

Brosseau, Carole, et al. �Prebiotics: Mechanisms and Preventive Effects in Allergy.� Nutrients, MDPI, 8 Aug. 2019, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31398959.

Kerr, Michael. �Seasonal Allergies: Symptoms, Causes, and Treatment.� Healthline, 7 May, 2018, www.healthline.com/health/allergies/seasonal-allergies.

Molinari, Giuliano, et al. �Respiratory Allergies: a General Overview of Remedies, Delivery Systems, and the Need to Progress.� ISRN Allergy, Hindawi Publishing Corporation, 12 Mar. 2014, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3972928/.

Newman, Tim. �Food Allergies: Symptoms, Treatments, and Causes.� Medical News Today, MediLexicon International, 17 July 2017, www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/14384.php.

Team, DFH. �Attack Allergies with Prebiotics.� Designs for health, 24 Oct. 2019, blog.designsforhealth.com/node/1133.

Unknown, Unknown. �Skin Allergies: Causes, Symptoms & Treatment.� ACAAI Public Website, 2019, acaai.org/allergies/types/skin-allergies.

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Functional Medicine, Gastro Intestinal Health, Gut and Intestinal Health, Health, Wellness

Do you feel:

- Edema and swelling in the ankles and the wrist?

- Muscle cramping?

- Frequent urination?

- Poor muscle endurance?

- Alternation in bowel regularity?

If you are experiencing any of these situations, then you might be experiencing chronic kidney disease.

About over 10% of the adult population suffers from CKD (chronic kidney disease), and the two leading underlying causes of the end-stage of chronic kidney disease are type 2 diabetes and hypertension. Other chronic ailments like dysbiosis of the gut microbiome, inflammation, oxidative stress, as well as environmental toxins and PPI (proton pump inhibitor). All these chronic ailments have been linked to chronic kidney disease in the body.

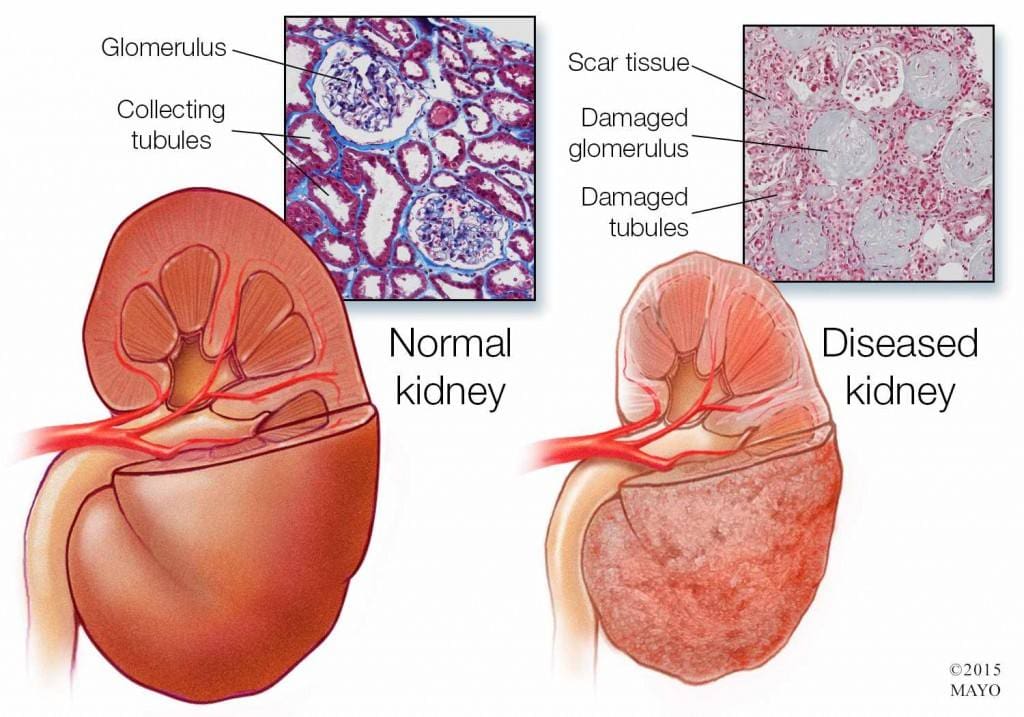

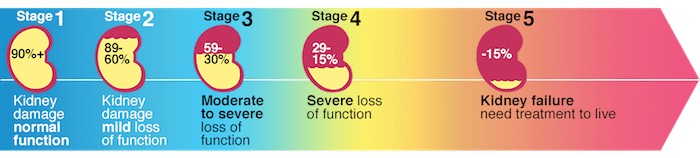

Chronic Kidney Disease

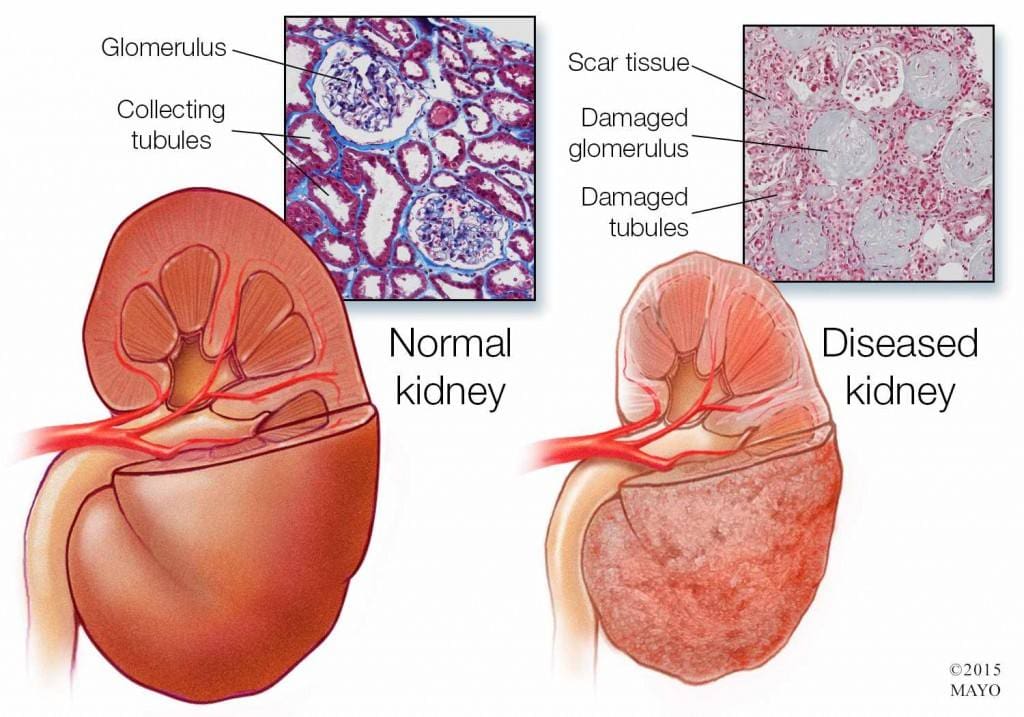

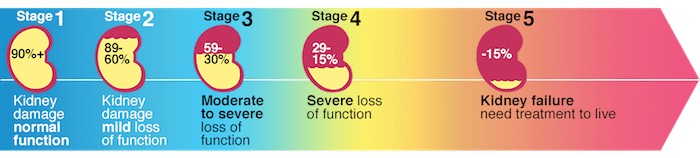

Chronic kidney disease is a slow and progressive loss of kidney function over several years. Also known as chronic renal failure, it much more widespread, and it often goes undetected and undiagnosed until the disease is well advanced. It is not unusual for anyone to realize they have chronic kidney failure when their kidneys are functioning only at 25% than average. As it advances and the kidney’s function is severely impaired, dangerous levels of waste and fluid can rapidly build up in the body.

Chronic kidney failure is different from acute kidney failure due to being a slow and gradually progressive disease. When the disease is fairly well advanced, the conditions are more severe than the signs and symptoms are noticeable, making most of the damage irreversible. Here are some of the most common signs and symptoms of chronic kidney disease include:

- Anemia

- Blood in urine

- Dark urine

- Edema- swollen feet, hands, ankles, and face

- Fatigue

- Hypertension

- More frequent urination, especially at night

- Muscle cramps and twitches

- Pain on the side or mid to lower back

Dietary Fibers for CKD

Researchers have investigated that the role of dietary fibers and the gut microbiome is in renal diets. When there is a dysbiosis in the gut microbiome, it can be a risk factor for the development of chronic kidney disease, thus reducing the renal function. That function will significantly contribute to dysbiosis. The current renal dietary recommendations include a reduction of protein intake with an increase in complex carbohydrates and fiber.

A systemic review did a test that included 14 controlled trials and 143 participants that had chronic kidney disease. The test demonstrated that all 143 participants had a reduction in serum creatinine and urea that is associated with dietary fiber intake, which occurs in a dose-dependent matter. These participants had an average intake of 27 grams of fiber per day in their diet. It is also an essential note that creatinine is metabolized in the intestinal bacteria in the body.

A high fiber diet can lead to the production of SCFAs (short-chain fatty acids) in the gastrointestinal tract. They play an essential role in T regulatory cell activation, which regulates the intestinal immune system. When there is dysregulation in the immune system, it can cause an increase of inflammation that may occur in chronic kidney disease. With a high fiber diet, the intake is associated with lowering the risk of inflammation and the mortality in kidney disease.

Increasing fiber intake is relatively easy with some of these high fiber foods that are both healthy and nutritious and can help individual’s that have kidney disease. These include:

- Pears

- Strawberries

- Avocados

- Apples

- Carrots

- Beets

- Broccoli

- Lentils

Research has previously demonstrated that a high fiber diet for CDK patients is characterized by the control increase of plant-origin protein and animal-origin foods. This is useful for individuals to limit the consumption of processed food products because of modern conservation processes, which has the purpose of eliminating pathogenic bacteria. People who have chronic kidney disease that go on a high fiber diet have been linked to better kidney function and lowering the risk of inflammation and mortality.

Some individuals may experience some gastrointestinal side effects when they are trying to increase their fiber intake.�Research has been stated that patients should consider resistant starches since it has shown no side effects with the recommended doses.

Conclusion

Chronic kidney disease is a slow and progressive loss of kidney function. The signs and symptoms are noticeable as the disease progress in the later stages. With a high fiber diet, individuals can lower the risk of inflammation and mortality of CDK. When this disease causes inflammation and chronic illness in the kidneys, complications can travel through the entire body. The high fiber diet can also be beneficial for the gut microbiome to function correctly, and some products can help lower the stress hormones and make sure that the body’s hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is functioning correctly.

October is Chiropractic Health Month. To learn more about it, check out Governor Abbott�s bill on our website to get full details on this historic moment.

The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal and nervous health issues as well as functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions. We use functional health protocols to treat injuries or chronic disorders of the musculoskeletal system. To further discuss the subject matter above, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

References:

D�Alessandro, Claudia. �Dietary Fiber and Gut Microbiota in Renal Diets.� MDPI, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 9 Sept. 2019, www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/11/9/2149/htm.

Gunnars, Kris. �22 High-Fiber Foods You Should Eat.� Healthline, 10 Aug. 2018, www.healthline.com/nutrition/22-high-fiber-foods.

Jurgelewicz, Michael. �New Article Investigates the Role of Dietary Fiber and the Gut Microbiome in Chronic Kidney Disease.� Designs for Health, 13 Sept. 2019, blog.designsforhealth.com/node/1105.

Khosroshahi, H T, et al. �Effects of Fermentable High Fiber Diet Supplementation on Gut Derived and Conventional Nitrogenous Product in Patients on Maintenance Hemodialysis: a Randomized Controlled Trial.� Nutrition & Metabolism., U.S. National Library of Medicine, 12 Mar. 2019, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=30911321.

Krishnamurthy, Vidya M Raj, et al. �High Dietary Fiber Intake Is Associated with Decreased Inflammation and All-Cause Mortality in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease.� Kidney International, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Feb. 2012, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4704855/.

Newman, Tim. �Chronic Kidney Disease: Symptoms, Causes, and Treatment.� Medical News Today, MediLexicon International, 13 Dec. 2017, www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/172179.php.

Staff, Mayo Clinic. �Chronic Kidney Disease.� Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 15 Aug. 2019, www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/chronic-kidney-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20354521.

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Functional Medicine, Gastro Intestinal Health, Gut and Intestinal Health, Health, Nutrition, Wellness

Do you feel:

- Inflammation in your joints?

- Unpredictable abdominal swelling?

- Frequent bloating and distention after eating?

- Unpredictable food reactions?

- Aches, pains, and swelling throughout the body?

If you are experiencing any of these situations, then you might be experiencing a low intake of fiber in your diet, causing inflammation.

Throughout several decades, Americans have lost much diversity in their diets, impacting their gut microbiome, and the contribution to the autoimmune disorder epidemic. The vast majority of people have a less than perfect diet that is consists of high in calories, short on nutrients, and low on fiber intake. Research has stated that about only 10 percent of Americans have met their daily fiber requirements.

The diet is a significant environmental trigger in autoimmune diseases. Dietary approaches can provide the most effective means of an individual to returning balance and the dysfunction with the gastrointestinal system. Researchers have found out that the role of dietary fibers can help with rheumatoid arthritis as there is new and developing research on this discovery.

What is Rheumatoid Arthritis?

Rheumatoid arthritis is a long term, progressive, and disabling autoimmune disease. It causes inflammation, swelling, and pain in and around the joints and organs of the body. It affects up to 1 percent of the world’s population and over 1.3 million people in America, according to the Rheumatoid Arthritis Support Network.

Rheumatoid arthritis is also a systemic disease, which means that it affects the whole body, not just the joints. It occurs when an individual’s immune system mistakes their body’s healthy tissues for foreign invaders. As the immune system responds to this, inflammation occurs in the target tissue or organ. Symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis can include:

- Pain, swelling, and stiffness in more than one joint

- Symmetrical joint involvement

- Joint deformity

- Unsteadiness when walking

- Fever

- A general feeling of being unwell

- Loss of function and mobility

- Weight loss

- Weakness

Fiber and Inflammation

Individuals who eat healthily knows that eating fibers in their diet can help reduce the risk of developing various conditions. The AHAEP (American Heart Association Eating Plan) has stated that people should be eating a variety of food fiber sources in their diet. The total dietary fiber intake that a person should be eating is 25 to 30 grams a day from foods, not supplements. Currently, adults in the United States eat about 15 grams a day on their fiber, which is half of the recommended amount.

Eating a high fiber diet can provide many rewards to the body. Eating fruits, vegetables, beans, nuts, and whole grains can provide a boost of vitamins, minerals, protein, and healthy nutrients in the body. Studies have been shown that eating a high fiber diet can help lower the markers of inflammation, which is a critical factor in many forms of arthritis.

The body needs two types of fibers, which are soluble and insoluble. Soluble fibers are mixed with water to form a gel-like consistency, which slows digestion and helps the body absorb nutrients better and helps lower total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol. Insoluble fibers help the digestive system run more efficiently as it adds bulk to stool, which can help prevent constipation.

There have been a few studies that found that people who eat high fiber diets have lower CRP (C-reactive protein) levels in their blood. CRP is a marker for inflammation and is linked to rheumatoid arthritis. When a person eats a high fiber diet, it not only reduces inflammation to their bodies, but it helps lower the body weight as well. High fiber-rich foods feed the beneficial bacteria living in the gut, and then it is releasing substances to the body, promoting lower levels of inflammation.

A study has been shown that patients with rheumatoid arthritis that they consumed either a high fiber bar or cereal for 28 days while continuing with their current medication had decreased levels of inflammation. Researchers noticed that they had an increase of T regulatory cell numbers, a positive Th1/Th17 ratio, a decrease in bone erosion, and a healthy gut microbiome.

Gut Health and Inflammation

The gut plays a crucial role in the immune function as well as digesting and absorbing food in the body. The intestinal barrier provides an effective protective barrier from pathogenic bacteria but also being a healthy environment for beneficial bacteria. With a high fiber diet, it can lead to the production of SCFAs (short-chain fatty acids) in the gastrointestinal tract, thus playing an essential role in T regulatory cell activation, which regulates the intestinal immune system. When inflammation comes to play in the gut, it can disrupt the intestinal permeability barrier and cause a disruption, leading to leaky gut. Probiotics and a high fiber diet can help prevent inflammation and provide a healthy gut function.

Conclusion

Eating a high fiber diet is essential to prevent inflammation, not on the joints, but everywhere in the body. Even though individuals eat half of the recommended amount of fiber in their diets, due to their hectic lifestyle, eating a high fiber diet is beneficial. Incorporating fiber in their diet gradually is ideal as well as drinking water with the fibers to make the process work more effectively in the body. Some products can help aid the body by supporting not only the gastrointestinal function and muscular system but making sure that the skin, hair, nail, and joints are healthy as well.

October is Chiropractic Health Month. To learn more about it, check out Governor Abbott�s declaration on our website to get full details on this historic moment.

The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal and nervous health issues as well as functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions. We use functional health protocols to treat injuries or chronic disorders of the musculoskeletal system. To further discuss the subject matter above, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

References:

at UCSF Medical Center, Healthcare Specialist. �Increasing Fiber Intake.� UCSF Medical Center, 2018, www.ucsfhealth.org/education/increasing_fiber_intake/.

Brazier, Yvette. �Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA): Symptoms, Causes, and Complications.� Medical News Today, MediLexicon International, 16 Oct. 2018, www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/323361.php.

Hakansson, Asa, and Goran Molin. �Gut Microbiota and Inflammation.� Nutrients, MDPI, June 2011, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3257638/.

Jurgelewicz, Michael. �New Study Demonstrates the Role of Fiber in Rheumatoid Arthritis.� Designs for Health, 11 Oct. 2019, blog.designsforhealth.com/node/1125.

Unknown, Unknown. �More Fiber, Less Inflammation?� Www.arthritis.org, 25 June, 2015, www.arthritis.org/living-with-arthritis/arthritis-diet/anti-inflammatory/fiber-inflammation.php.