Gut and Intestinal Health

Back Clinic Gut and Intestinal Health. The health of an individual’s gut determines what nutrients are absorbed along with what toxins, allergens, and microbes are kept out. It is directly linked to the health of the whole body. Intestinal health could be defined as optimal digestion, absorption, and assimilation of food. But this is a job that depends on many other factors. More than 100 million Americans have digestive problems. Two of the top-selling drugs in America are for digestive problems, and they run in the billions. There are more than 200 over-the-counter (OTC) remedies for digestive disorders. And these can and do create additional digestive problems.

If an individual’s digestion is not working properly, the first thing is to understand what is sending the gut out-of-balance in the first place.

- A low-fiber, high-sugar, processed, nutrient-poor, high-calorie diet causes all the wrong bacteria and yeast to grow in the gut and damages the delicate ecosystem in your intestines.

- Overuse of medications that damage the gut or block normal digestive function, i.e., acid blockers (Prilosec, Nexium, etc.), anti-inflammatory medication (aspirin, Advil, and Aleve), antibiotics, steroids, and hormones.

- Undetected gluten intolerance, celiac disease, or low-grade food allergies to foods such as dairy, eggs, or corn.

- Chronic low-grade infections or gut imbalances with overgrowth of bacteria in the small intestine, yeast overgrowth, parasites.

- Toxins like mercury and mold toxins damage the gut.

- Lack of adequate digestive enzyme function from acid-blocking medications or zinc deficiency.

- Stress can alter the gut’s nervous system, cause a leaky gut, and change the normal bacteria.

Visits for intestinal disorders are among the most common trips to primary care doctors. Unfortunately, most, which also includes most doctors, do not recognize or know that digestive problems wreak havoc in the entire body. This leads to allergies, arthritis, autoimmune disease, rashes, acne, chronic fatigue, mood disorders, autism, dementia, cancer, and more. Having proper gut and intestinal health is absolutely central to your health. It is connected to everything that happens in the body.

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Functional Medicine, Gastro Intestinal Health, Gut and Intestinal Health, Health, Wellness

Do you feel the following:

- Feeling those bowels do not empty completely

- Lower abdominal pain relieved by passing stool or gas

- Alternating constipation and diarrhea

- A hard, dry, or small stool

- Use laxatives frequently

If you are experiencing any of these situations, then you must be experiencing gastrointestinal impairments in your body.

Gastrointestinal Impairments

The digestive system is consisting of the gastrointestinal tract, which is home to the intestines, the liver, the colon, the gallbladder, the pancreas, and the stomach. When there is a disruption in the gastrointestinal tract, it can cause inflammation and chronic illnesses that can harm the body. Functional disorders in the digestive tract (GI tract) can look normal in the body, but it doesn’t work correctly.

Many factors can upset the GI tract and its motility, including:

- Eating a diet low in fiber

- Not getting enough exercise

- Traveling or changes in a routine

- Eating large amounts of dairy blankets

- Stress

- Resisting the urge to have a bowel movement

- Overusing laxatives

- Taking certain medicines

Some of the most common problems that can affect the GI tract are constipation, IBS, and colon cancer.

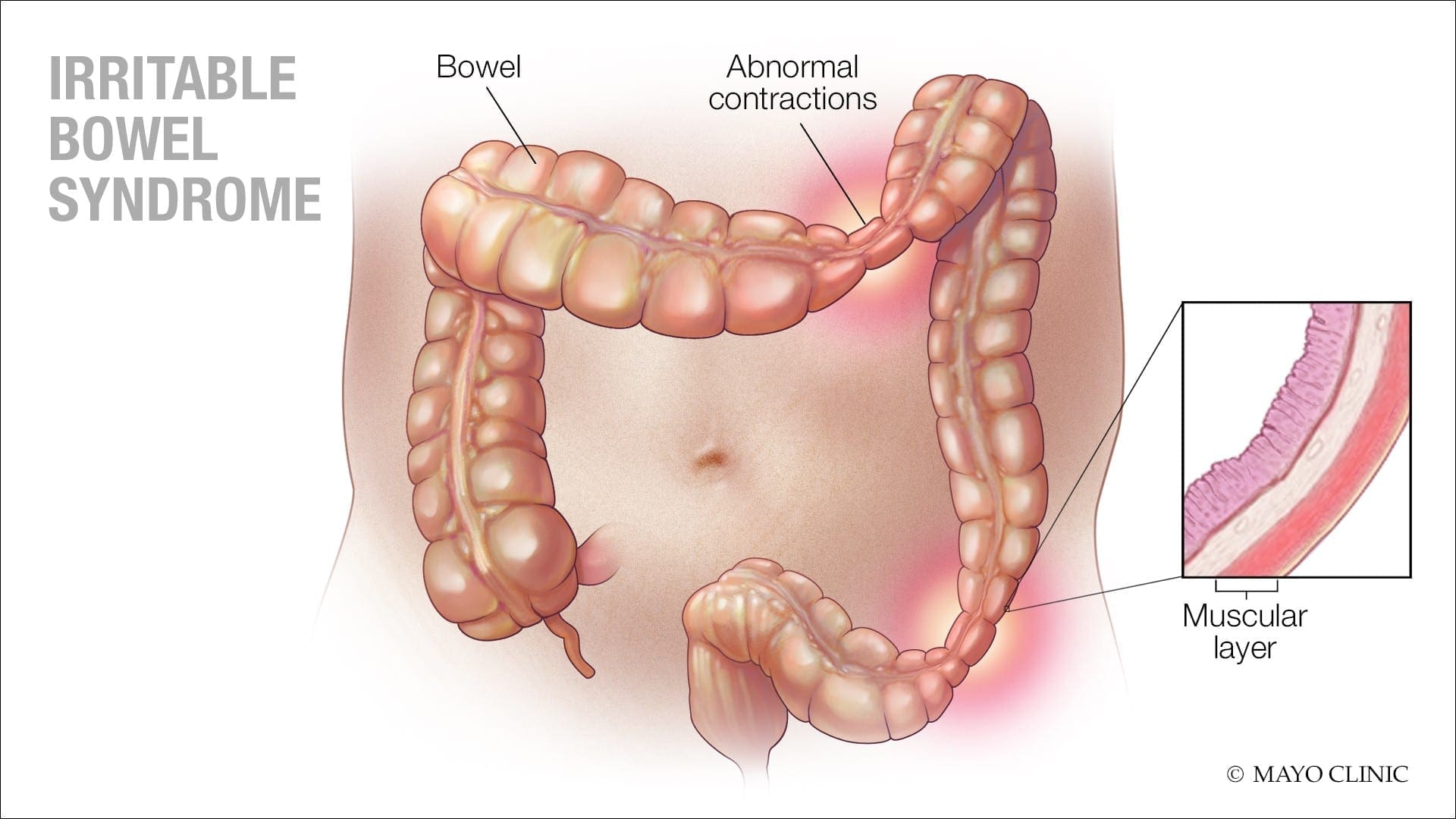

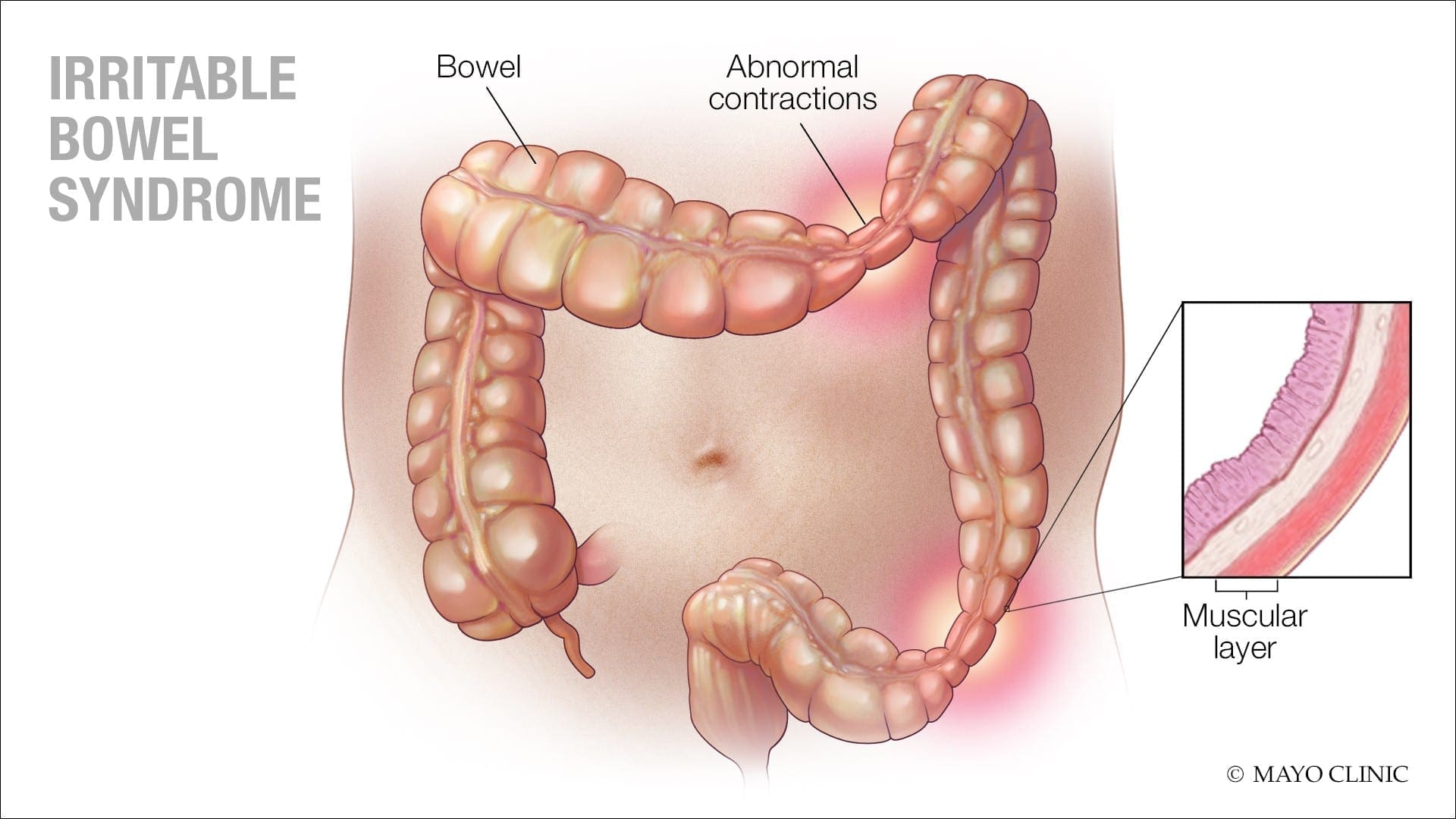

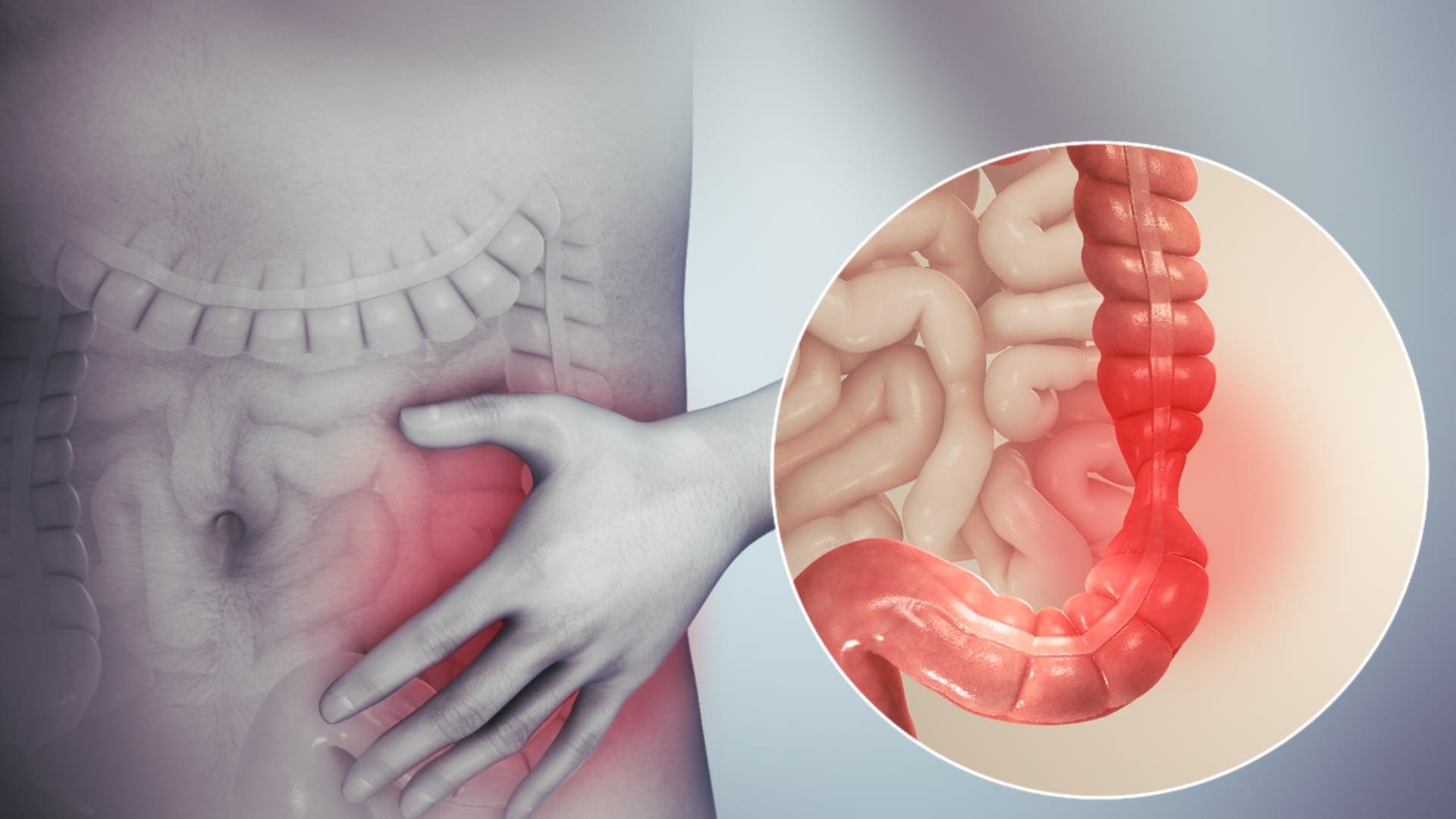

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

IBS (irritable bowel syndrome) is a long term gastrointestinal disorder. It can cause abdominal pain, bloating, mucus in the stool, irregular bowel habits, and can alternate diarrhea and constipation. IBS can cause persistent discomfort to individuals, but they can improve the symptoms over time as they learn to manage the condition.

Some of the symptoms caused by IBS are:

- Changes in bowel habits

- Abdominal pain and cramping that lessens after using the bathroom

- A feeling that the bowels not fully emptied after using the bathroom

- Excess gas

- The passing of mucus from the rectum

- The sudden urgent need to use the bathroom

- Swelling or bloating from the abdomen.

Signs and symptoms of IBS can vary between individuals and can often resemble other diseases and conditions. IBS symptoms can often get worst after earing, and a flare-up may last about 2 to 4 days, then the symptoms may either improve or go away entirely, but IBS symptoms can affect different body parts.

These can include:

- Frequent urination

- Bad breath

- Headaches

- Joint or muscle pain

- Persistent fatigue

- Anxiety

- Depression

Constipation

Constipation is one of the most common digestive problems that affects around 2.5 million individuals. It is a syndrome that is defined by bowel symptoms (painful or infrequent passage of stool, the hardness of stool, or a feeling of incomplete evacuation) that may occur either in isolation or secondary to another underlying disease like for example, Parkinson’s disease.

The cause of constipation is through the colon. The colon’s main job is to absorb water from leftover food as it passes through the digestive system and creates waste. When the waste is ready to be excreted out, the colon’s muscles propel the waste out through the rectum to eliminate from the body. If the debris remains in the colon for too long, though, it can be tough and challenging to excrete it out of the body.

Some factors can cause constipation; this can include:

- Stress

- Low-fiber diet

- Lack of exercise

- Certain medications

- Particular diseases like a stroke, Parkinson’s disease, and diabetes

- Problems with the colon or rectum

- Hormonal issues

Everyone’s definition of a regular bowel movement may be different. Some people can go about three times a day, while others can go to relieve themselves about three times a week. Some of the symptoms of constipation included are:

- Fewer than three bowel movements a week

- Passing hard, dry stools

- Straining or pain during bowel movements

- Still feeling full after a bowel movement

- Experiencing a rectal blockage

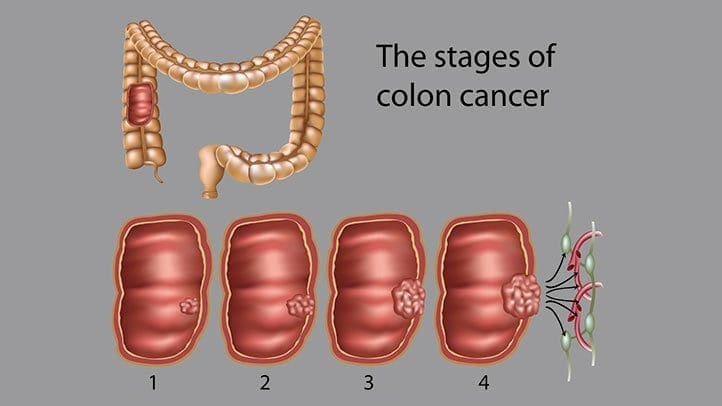

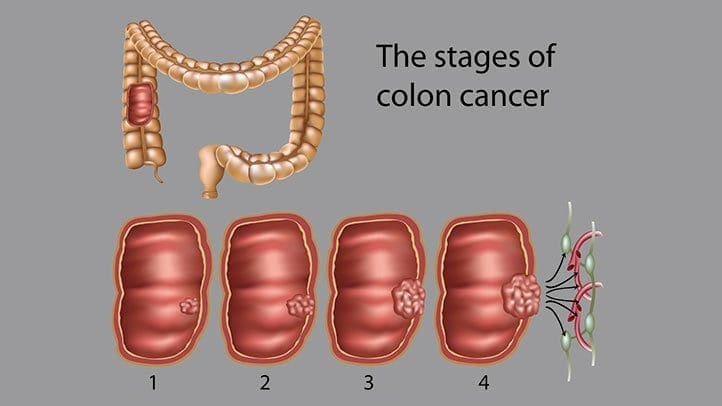

Colon Cancer

Colon cancer is the third most common type of cancer. When tumorous growths develop in the large intestine or the colon, it develops colon cancer in the GI tract. The colon, the one organ where the body draws out water and salt from solid wastes. The waste then moves through the rectum and excretes out of the body through the anus.

Even though colon cancer doesn’t cause any symptoms in the earliest stages, but it can become more noticeable as the disease progresses. Some of the sign and symptoms of colon cancer include:

- Diarrhea or constipation

- Changes in stool consistency

- Loose, narrow stools

- Blood in the stool

- Abdominal pain

- Weakness and fatigue

- Iron deficiency

If colon cancer spreads to a new location the gastrointestinal system, it can cause additional problems in the new area.

Conclusion

Having gastrointestinal impairments can cause the body to develop chronic illnesses. There are ways to make sure that the digestive tract is functioning correctly. An individual can change their diets and lifestyle and can make sure that their gut is working properly. When there is a disruption in the GI tract like IBS, constipation, and colon cancer, it can lead to many health problems if the individual is not careful. If an individual prolongs the symptoms, then they will develop life-long issues for their body. Some products help support the intestinal tract and help strengthens the natural defenses and support the intestinal immune function.

October is Chiropractic Health Month. To learn more about it, check out Governor Abbott�s declaration on our website to get full details on this historic moment.

The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal and nervous health issues as well as functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions. We use functional health protocols to treat injuries or chronic disorders of the musculoskeletal system. To further discuss the subject matter above, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

References:

Bharucha, Adil E, et al. �American Gastroenterological Association Technical Review on Constipation.� Gastroenterology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Jan. 2013, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3531555/.

Brazier, Yvette. �Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): Symptoms, Diet, Causes, and Treatment.� Medical News Today, MediLexicon International, 18 Dec. 2017, www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/37063.php.

Crosta, Peter. �Colon Cancer: Symptoms, Treatment, and Causes.� Medical News Today, MediLexicon International, 28 Aug. 2019, www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/150496.php.

Sethi, Saurabh. �What You Should Know About Constipation.� Healthline, 23 Aug. 2019, www.healthline.com/health/constipation.

Unknown, Unknown. �Digestive Disorders & Gastrointestinal Diseases.� Cleveland Clinic, 2017, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/7040-gastrointestinal-disorders.

Whitfield, K Lynette, and Robert J Shulman. �Treatment Options for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: from Empiric to Complementary Approaches.� Pediatric Annals, U.S. National Library of Medicine, May 2009, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2830707/.

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Functional Medicine, Gut and Intestinal Health, Hormone Balance, Wellness

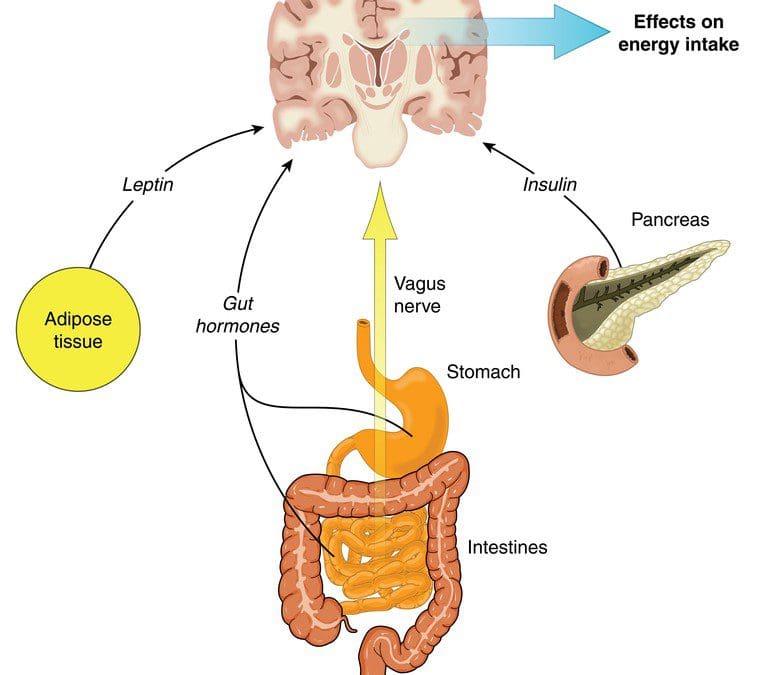

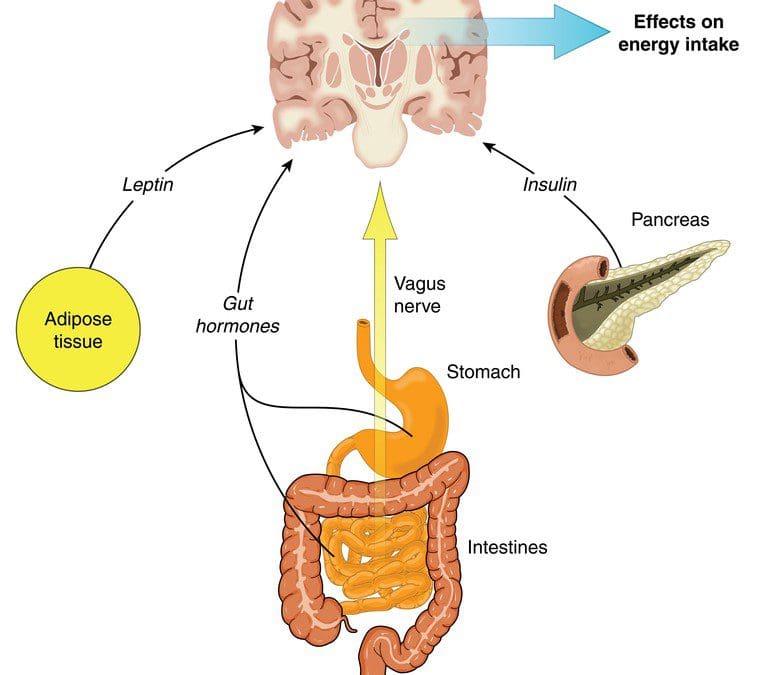

Microbes have multicellular hosts and can have many effects on the host�s health and well-being. Researchers have stated that microbes influence metabolism, immunity, and behavior on the human body. One of the most important but understudied mechanisms that microbes have is that they can involve hormones. In the presence of gut microbiota, specific changes in hormone levels can correlate in the gut. The gut microbiota can produce and secrete hormones, respond to the host hormones, and regulate their expression levels. There is also a link between the endocrine system and the gut microbiota as more information is still being researched.

The Gut to Hormone Connection

Since the human microbiome contains a vast array of microbes and genes that shows a higher complexity. Unlike other organs in the body, the gut microbiota’s function is not fully understood yet but can be disrupted easily by antibiotics, diet, or surgery. The best-characterized function is how the gut microbiota interacts with the endocrine system in the body.

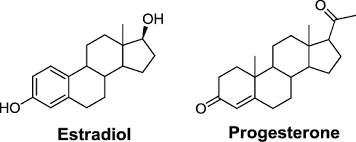

Emerging research has indicated that the gut microbiome plays a central role in regulating estrogen levels within the body. When the estrogen hormone levels are too high or too low, it can lead to the risk of developing estrogen-related diseases like endometriosis, polycystic ovary syndrome, breast cancer, and prostate cancer to males and females.

The gut to hormone connection is essential since the gut is one of the producers to create hormones that travel through the entire body system. With the endocrine system is being involved, it is the first network to produce and transport hormones to the organs that need the hormones to function. When there is an imbalance of hormones in the human body, it can disrupt all the other hormones.

The gut microbiota influences nearly every hormone that the endocrine system creates, including:

- The thyroid hormones

- Estrogen hormones

- Stress hormones

Thyroid Hormones

If the gut has inflammation, then the hormones in the body will create an excessive or low quantity in the body. If the endocrine glands like thyroid, are producing a low quantity of hormones and the gut can be imbalanced and lead to hypothyroidism. When there is low microbial diversity in the gut, studies have shown that the low microbial diversity is linked to high TSH (thyroid-stimulating hormone) levels. The excessive quantity of thyroid hormones can lead to hyperthyroidism. Both hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism can cause symptoms like irritability, anxiety, poor memory, and many symptoms that can affect the body.

“If you are experiencing excessive belching, burping, bloating, difficult bowel movements difficulty digesting proteins and meats; undigested food found in stools, digestive problems subside with rest and relaxation or any symptoms. Then this article will give you a better understand what is happening with the gut and how hormones can affect the gut system.”

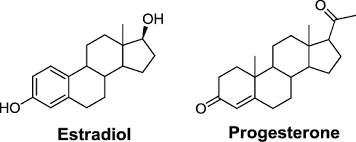

Estrogen Hormones

The gut and an individual’s hormones are meant to be in communication with each other. They not only support each other, but they also work together to make sure the body is running smoothly. Studies have found out that the gut’s intestinal cells have special receptors for hormones that allow them to detect any hormonal shifts that affect the body.

Since estrogen is typically associated with women, it is common that men need the right amount of estrogen levels to function. The gut microbiota is the key regulator of leveling and circulating estrogen in the body. The microbes produce an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase, which then converts the estrogen hormone to its active form.

The gut microbiome can regulate estrogen levels by functioning a specific bacteria in the microbiome called estrobolome. Estrobolome is the aggregates of enteric bacterial genes that are capable of metabolizing estrogen. It might affect women’s risk of developing postmenopausal estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. The estrobolome is highly essential to keep estrogen levels in the body at a stable state.

In the gut microbiota, both the estrogen and progesterone hormones can impact the guts’ motility and peristalsis ( The rhythmic movement of the intestines that move food through the stomach and out of the body) by playing opposing roles in the guts� motility. Progesterone helps slow down the gut�s motility by relaxing the smooth and slowing transit the time the food is moving out of the body. Estrogen helps increase the contraction of the smooth muscles in the intestines. When the estrogen hormones are leveled right, it can help keep the gut moving smoothly and help increase the diversity of the body�s microbiomes, which is a good thing for the immune system.

Stress Hormones

Stress hormones or cortisol plays a massive part in the gut microbiota. Since cortisol hormones connect to the brain, it sends the signals to the gut and vice versa. If it is a short stressor like getting ready for a presentation or a job interview, the person will feel “butterflies” in their gut. The longer stressors, for example, like having a highly stressful job or feeling anxious consistently, can lead to chronic illnesses in the gut like inflammation or leaky gut. Since the hormone and gut connection is in sync with the gut and brain connection, it is crucial to lowering the cortisol levels to a stable state for a healthy functional body.

Conclusion

The gut and hormone connections are profoundly meaningful since they are linked closely together. When there is a disruption on the gut, it can cause hormones to be imbalanced, causing many disruptions like inflammation and leaky gut. When there is a disruption in the hormones, it can disrupt the gut as well by negatively shifting the gut’s microbiome. So to ensure that the gut is functioning correctly, it is crucial to eat food that contains probiotics and is fermented to keep the gut flora healthy. Some products can help counter the metabolic effects of temporary stress and supporting estrogen metabolism by incorporating other essential nutrients and cofactors to support the endocrine system.

October is Chiropractic Health Month. To learn more about it, check out Governor Abbott�s declaration on our website to get full details on this historic moment.

The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal and nervous health issues as well as functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions. We use functional health protocols to treat injuries or chronic disorders of the musculoskeletal system. To further discuss the subject matter above, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

References:

Author, Guest. �How Your Gut Microbiome Influences Your Hormones.� Bulletproof, 21 Aug. 2019, www.bulletproof.com/gut-health/gut-microbiome-hormones/.

Evans, James M, et al. �The Gut Microbiome: the Role of a Virtual Organ in the Endocrinology of the Host.� The Journal of Endocrinology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 28 Aug. 2013, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23833275.

Kresser, Chris. �The Gut�Hormone Connection: How Gut Microbes Influence Estrogen Levels.� Kresser Institute, Kresserinstitute.com, 10 Oct. 2019, kresserinstitute.com/gut-hormone-connection-gut-microbes-influence-estrogen-levels/.

Kwa, Maryann, et al. �The Intestinal Microbiome and Estrogen Receptor-Positive Female Breast Cancer.� Journal of the National Cancer Institute, Oxford University Press, 22 Apr. 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5017946/.

Neuman, Hadar, et al. �Microbial Endocrinology: the Interplay between the Microbiota and the Endocrine System.� OUP Academic, Oxford University Press, 20 Feb. 2015, academic.oup.com/femsre/article/39/4/509/2467625.

Publishing, Harvard Health. �The Gut-Brain Connection.� Harvard Health, 2018, www.health.harvard.edu/diseases-and-conditions/the-gut-brain-connection.

Szkudlinski, Mariusz W, et al. �Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone and Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone Receptor Structure-Function Relationships.� Physiological Reviews, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Apr. 2002, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11917095.

Wieselman, Brie. �Why Your Gut Health and Microbiome Make-or-Break Your Hormone Balance.� Brie Wieselman, 28 Sept. 2018, briewieselman.com/why-your-gut-health-and-microbiome-make-or-break-your-hormone-balance/.

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Functional Medicine, Gut and Intestinal Health, Health, Hormone Balance, Wellness

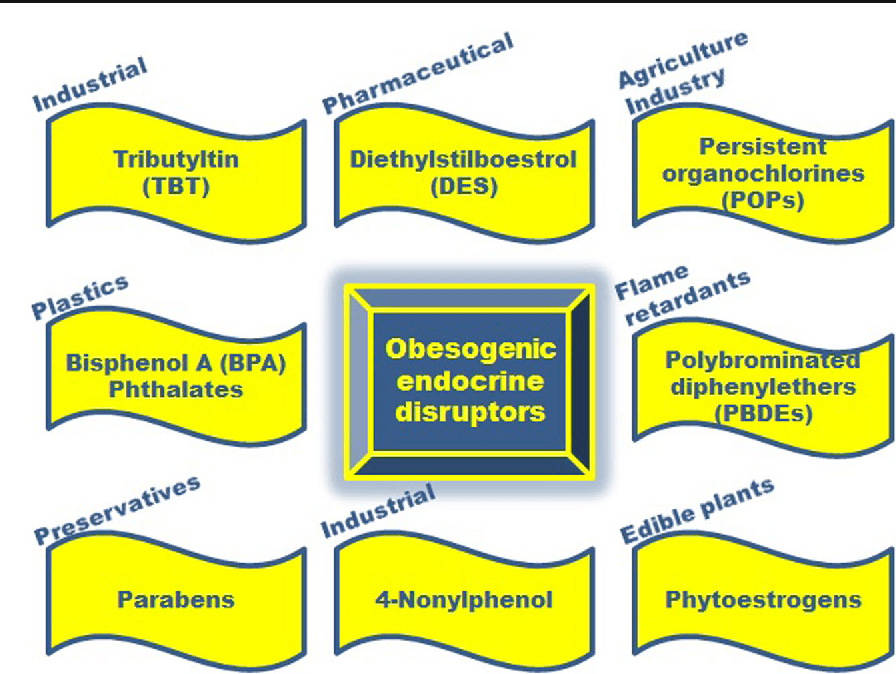

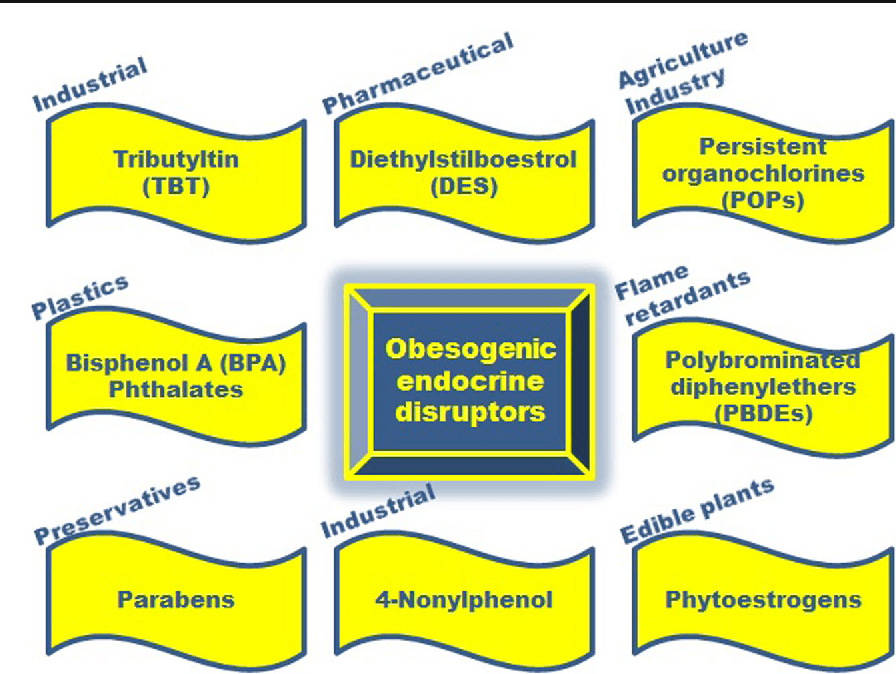

Endocrine disruptors are chemicals that may interfere with the body’s endocrine system and produce adverse developmental, reproductive, neurological, and immune effects in humans. It can be pesticides, plasticizers, antimicrobials, and flame retardants that can be EDCs. EDCs (endocrine-disrupting chemicals) can disrupt the hormonal balance and can result in developmental and reproductive abnormalities in the body.

There are four points about endocrine disruption:

- Low dose matters

- Wide range of health benefits

- Persistence of biological effects

- Ubiquitous exposure

EDC can cause significant risks to humans by targeting different organs and systems in the body. The interactions and the mechanisms of toxicity created by EDC and environmental factors can be concerning a person’s general health problems. Including endocrine disturbances in the body since many factors can cause endocrine disruptors, one of the disruptors in the food contaminated with PBDEs (polybrominated diphenyl esters) in fish meat and dairy.

Researchers also pointed out that once the contaminated foods eliminated from a person’s diet, then the endocrine disruptors decline, and the body began to heal properly. When a person eliminates the food that is causing discomfort to their bodies, they are more aware of reading the food labels to prevent discomfort anymore to the body systems.

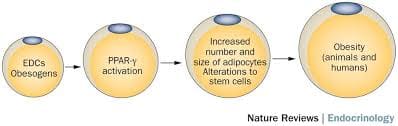

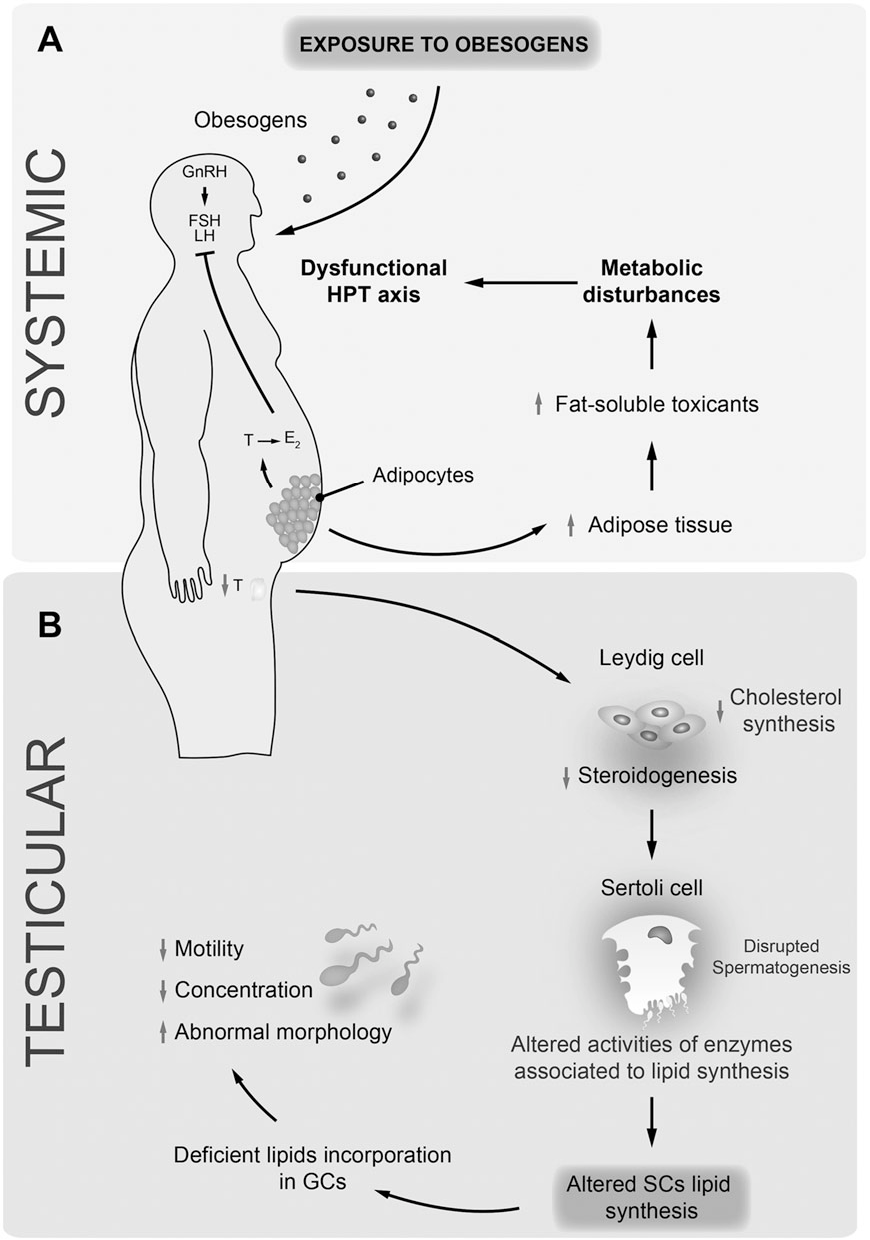

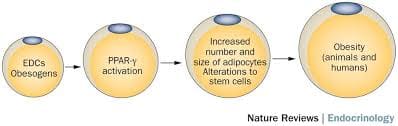

Obesogen

Obesogen is a subclass of endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDC) that might predispose individuals to the development of obesity. Their structure is mainly lipophilic, and they can increase fat deposition. Since the fat cell’s primary role is to store and release energy, researchers have found that different obesogenic compounds may have different mechanisms of action.

Some of these actions can affect the number of fat cells that are producing, while others affect the size of the fat cells, and some obesogenic compounds can affect the hormones. These compounds will affect the appetite, satiety, food preferences, and energy metabolism when the endocrine system plays a fundamental role in the body to regulate the metabolism of fats, carbohydrates, and proteins. Any alternations in the body can result in an imbalance in the metabolism and causing endocrine disorders.

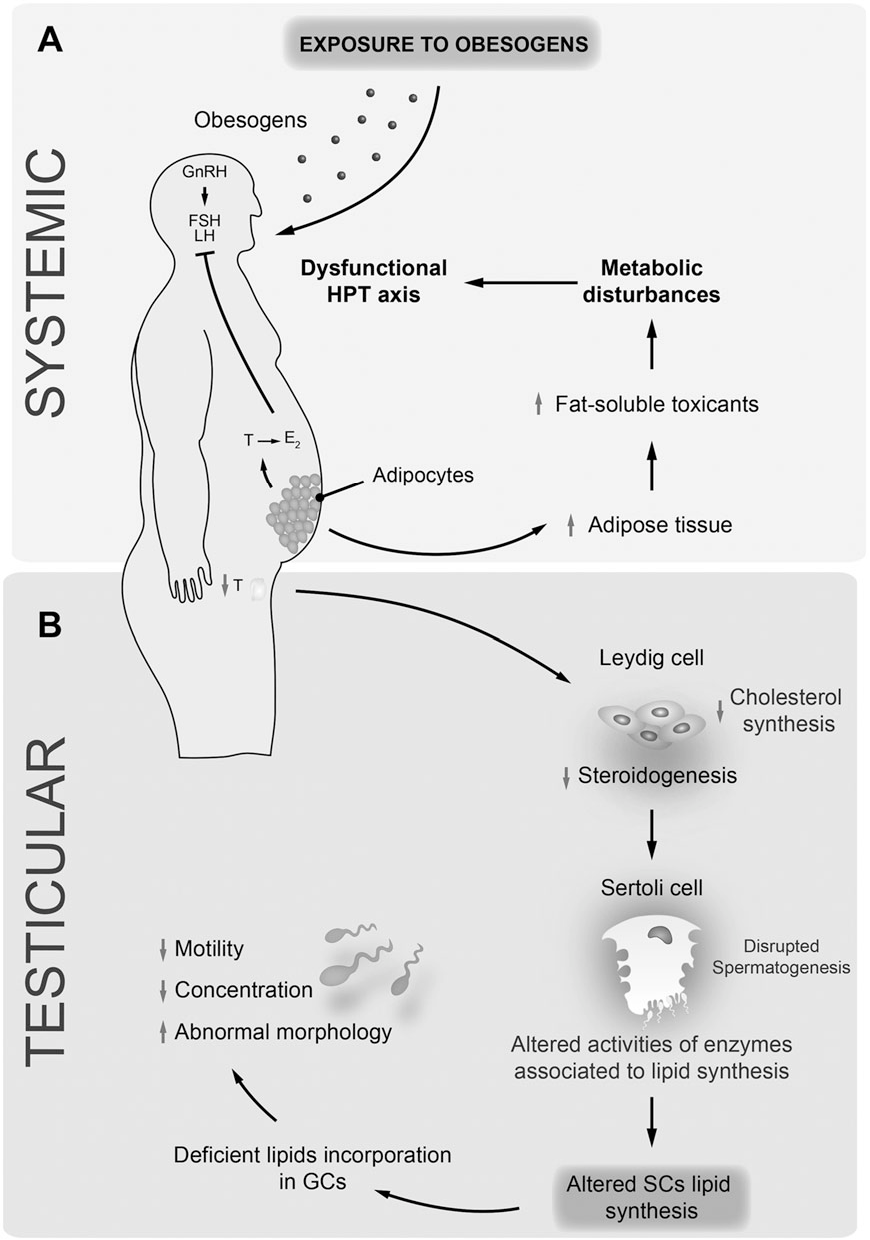

Studies even stated that exposure to obesogens could be found either before birth on utero or in the neonatal period. Obesogens can even cause a decrease in male fertility. When this disruption happens to the male body, environmental compounds can cause a predispose to weight gain, and obesogens can appoint as one of the contributors because of their actions as endocrine disruptors. Obesogens can even change the functioning of the male reproductive axis and testicular physiology. The metabolism in the male human body can be pivotal for spermatogenesis due to these changes.

Endocrine Disruptors and Obesity

Some endocrine disruptors that can affect the body can be through pharmaceutical drugs that can cause weight gain. A variety of prescription drugs can have an adverse effect that can result in weight gain since the chemicals found in prescription drugs have similar structures, and modes of action might have a role in obesity. Prescription medicine can stimulate the gut to consume more food, thus involving the body to gain weight.

Another endocrine disruptor is PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons). These are a family of environmental chemicals that occur in oil, coal, and tar deposits. They produce as by-products of fuel-burning like fossil fuel, biomass, cigarette smoke, and diesel exhaust. PAHs can either be manufactured to be used as medicines and pesticides or be released naturally from forest fires and volcanoes.

There are standard ways a person can be exposed to PAHs. One is through eating grilled, charred, or charcoal-broiled meats that a person eats. The other is through inhalation of smoke from cigarettes, vehicle exhaust, or emissions from fossil fuels that can irritate the eyes and breathing passageways in the body.

Coping with EDC Exposure

Even though obesity can adversely affect the body in a variety of health outcomes, there are ways to cope and minimize the exposure of EDC. Research shows that a person can minimize EDC exposure by consuming organic fruits, vegetables, and grain products insofar as possible. This includes an increasing number of fungicides routinely applied to fruits and vegetables that are being identified as obesogens and metabolic disruptors in the body.

Xenoestrogen vs. Phytoestrogen

When a person has an endocrine disorder, it might be due to the food they are consuming. Phytoestrogens are plant-derived compounds that are in a wide variety of food, mostly in soy. They are presented in numerous dietary supplements and widely marketed as a natural alternative to estrogen replacement therapy.

There is a health impact on phytoestrogen, and the plant-derived compound can either mimic, modulate, or disrupt the actions of endogenous estrogen. Xenoestrogen�are synthetically derived chemical agents from certain drugs, pesticides, and industrial by-products that mimic endogenous hormones or can interfere with endocrine disruptors. These chemical compounds can cause an effect on several developmental anomalies to humans. It can also interfere with the production and metabolism of ovarian estrogen in females.

Conclusion

Endocrine disruptors can interfere with the body’s endocrine system causing a health risk to an individual. EDC (endocrine-disrupting chemicals) can target many different organs and systems of the body by various factors that the human body is being exposed to. One of the EDC factors is obesogen, and it can cause a person to gain weight and be obese. Another factor is the exposure of PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) through environmental factors like smoke inhalation or consuming charcoal-broiled meats. There are ways to cope with EDC exposure, and one is eating organic foods, especially fresh fruits and vegetables. Another is products that target the endocrine system and helps support the liver, intestines, body metabolism, and estrogen metabolism to ensure not only a healthy endocrine system but also a healthy body to function correctly.

October is Chiropractic Health Month. To learn more about it, check out Governor Abbott’s proclamation on our website to get full details on this historic event.

The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal and nervous health issues as well as functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions. We use functional health protocols to treat injuries or chronic disorders of the musculoskeletal system. To further discuss the subject matter above, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

References:

Cardoso, A M, et al. �Obesogens and Male Fertility.� Obesity Reviews : an Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Jan. 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27776203.

Darbre, Philippa D. �Endocrine Disruptors and Obesity.� Current Obesity Reports, Springer US, Mar. 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5359373/.

Holtcamp, Wendee. �Obesogens: an Environmental Link to Obesity.� Environmental Health Perspectives, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Feb. 2012, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3279464/.

Janesick, Amanda S, and Bruce Blumberg. �Obesogens: an Emerging Threat to Public Health.� American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, May 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4851574/.

Janesick, Amanda S, and Bruce Blumberg. �Obesogens: an Emerging Threat to Public Health.� American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, May 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26829510.

Kyle, Ted, and Bonnie Kuehl. �Prescription Medications & Weight Gain.� Obesity Action Coalition, 2013, www.obesityaction.org/community/article-library/prescription-medications-weight-gain/.

L�r�nd, T, et al. �Hormonal Action of Plant Derived and Anthropogenic Non-Steroidal Estrogenic Compounds: Phytoestrogens and Xenoestrogens.� Current Medicinal Chemistry, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2010, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20738246.

Patisaul, Heather B, and Wendy Jefferson. �The Pros and Cons of Phytoestrogens.� Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Oct. 2010, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3074428/.

Singleton, David W, and Sohaib A Khan. �Xenoestrogen Exposure and Mechanisms of Endocrine Disruption.� Frontiers in Bioscience : a Journal and Virtual Library, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 1 Jan. 2003, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12456297.

Unknown, Unknown. �Endocrine Disruptors.� National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2015, www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/agents/endocrine/index.cfm.

Unknown, Unknown. �Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs): Your Environment, Your Health | National Library of Medicine.� U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, 31 Apr. 2017, toxtown.nlm.nih.gov/chemicals-and-contaminants/polycyclic-aromatic-hydrocarbons-pahs.

Yang, Oneyeol, et al. �Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: Review of Toxicological Mechanisms Using Molecular Pathway Analysis.� Journal of Cancer Prevention, Korean Society of Cancer Prevention, 30 Mar. 2015, www.jcpjournal.org/journal/view.html?doi=10.15430%2FJCP.2015.20.1.12.

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Detoxification, Functional Medicine, Gut and Intestinal Health, Hormone Balance, Wellness

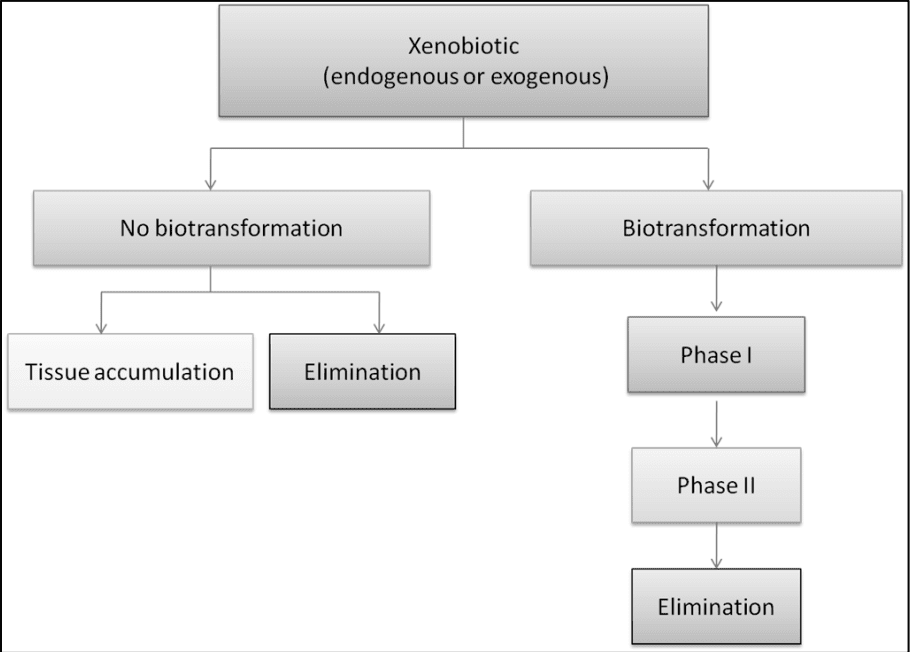

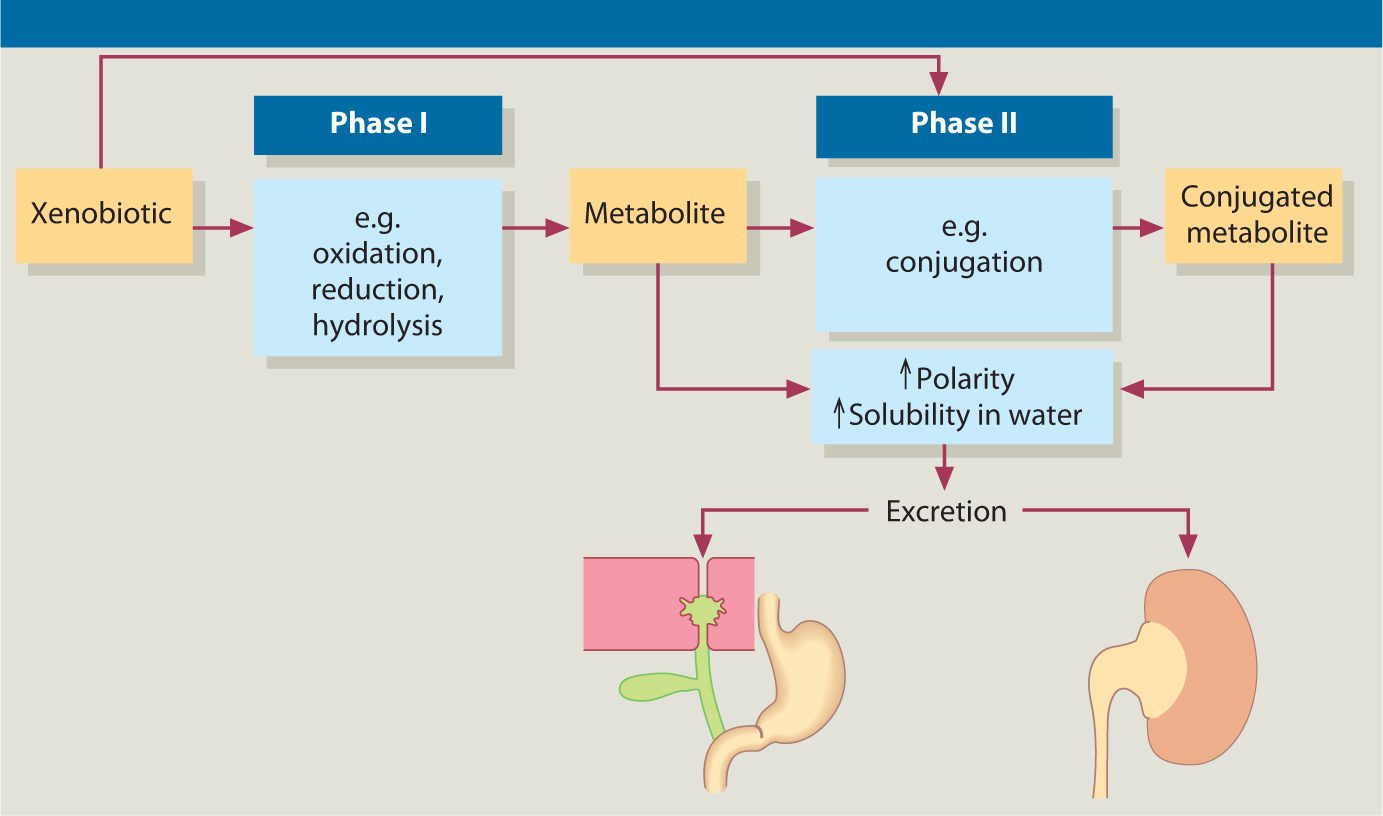

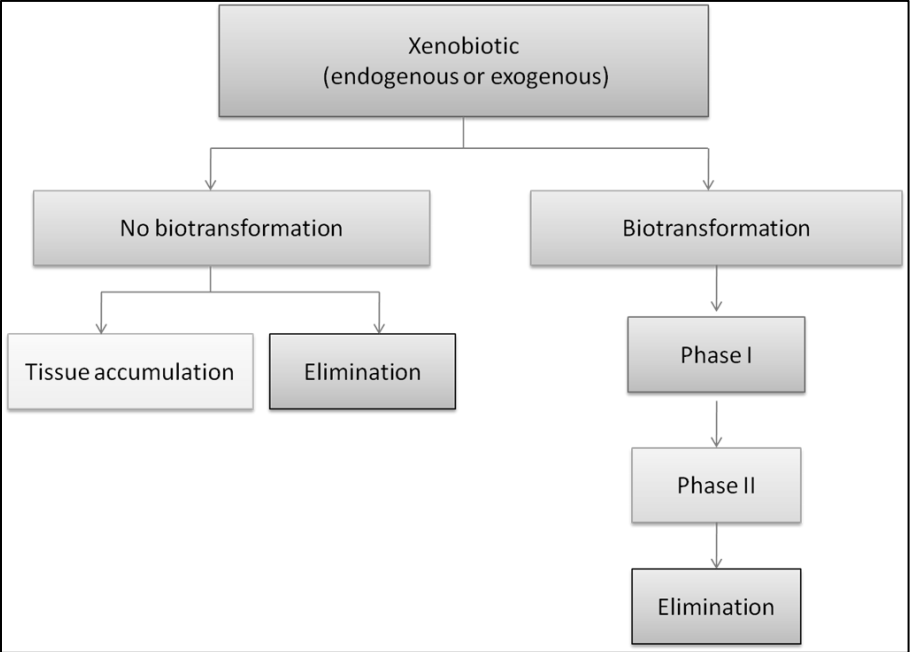

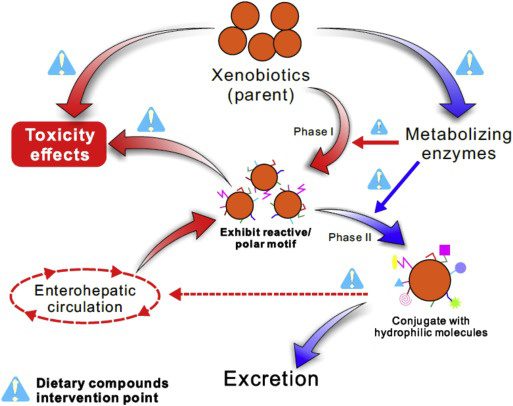

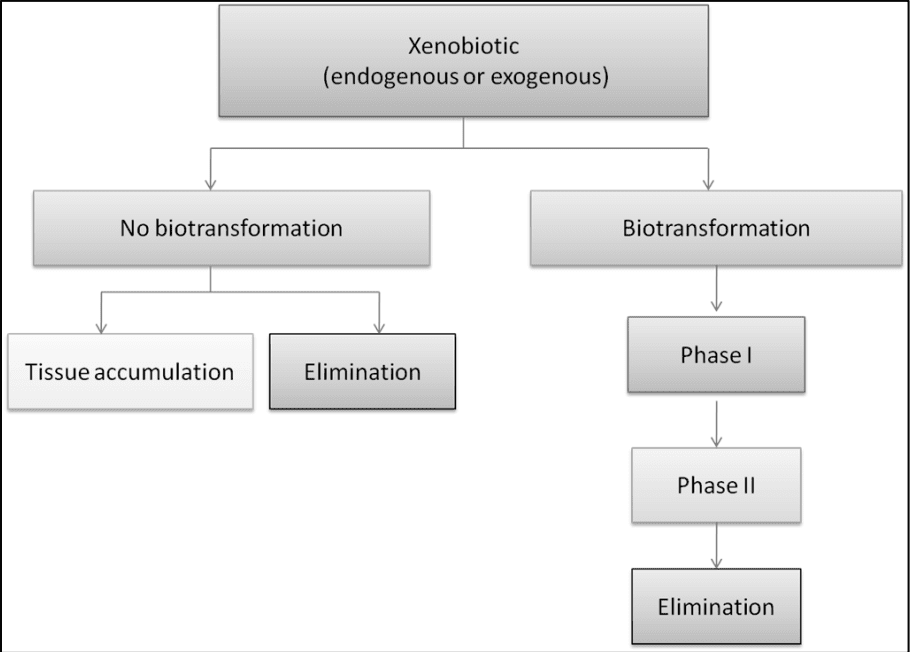

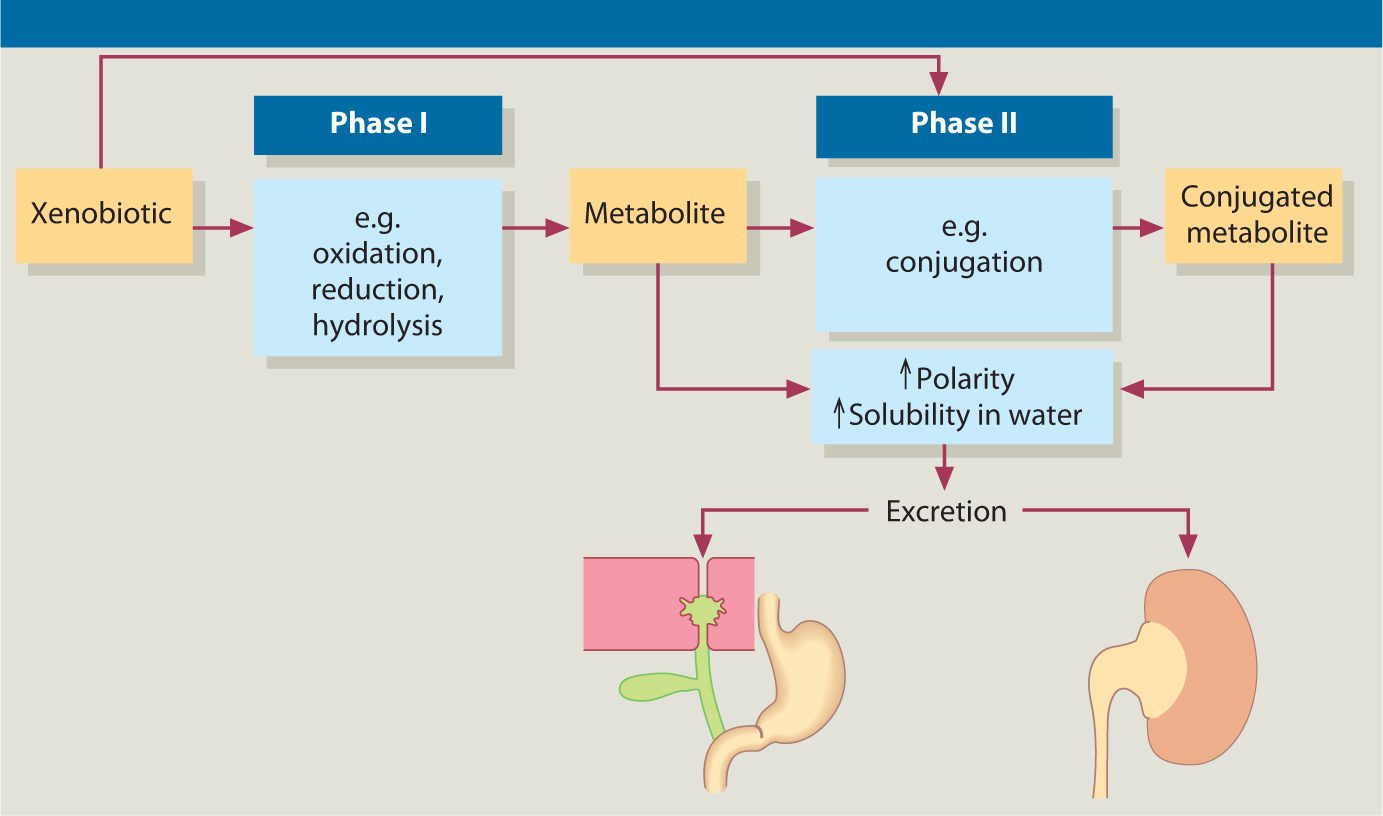

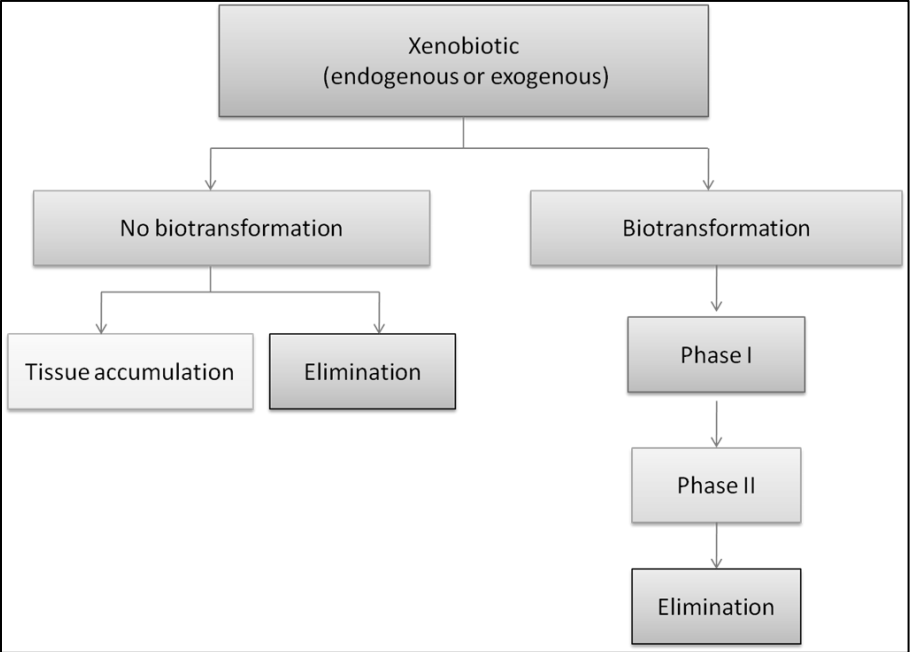

Biotransformation is the process of a substance changes from one chemical to another being transformed by a chemical reaction within the body. In the human body though, biotransformation is the process of rendering nonpolar (fat-soluble) compounds to polar (water-soluble) substances so they can be excreted in urine, feces, and sweat. It also serves as an important defense mechanism in the body to eliminate toxic xenobiotics out of the body through the liver. The liver is the one that takes these toxins and transformed them into suitable compounds to excrete out of the body as biotransformation.

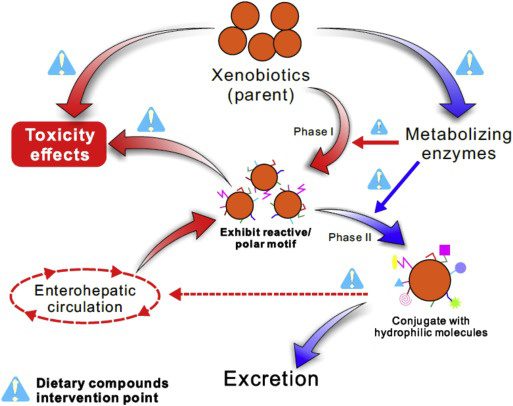

Detoxification is also known as �detoxication� in literature. It is also a type of alternative medicine treatment that aims the body to get rid of unspecified �toxins.� It is highly important for a person to detox their body and with biotransformation, it can be classified into two categories, under normal sequences, which tends to react with a xenobiotic. They are called Phase 1 and Phase 2 reactions that help the body with detoxification.

Phase 1 Reactions

Phase 1 reaction is consisting of oxidation-reduction and hydrolysis. Research shows that Phase 1 is generally the first defense employed by the body to biotransform xenobiotics, steroid hormones, and pharmaceuticals. They create CYP450 (cytochrome P450) enzymes and are described as functionalization microsomal membrane-bound that are located in the liver but can also be in enterocytes, kidney, lungs and the brain in the body. The CYP450 enzymes can be beneficial or have consequences for an individual�s response to the effect of a toxin they are exposed to.

Studies have been shown that phase 1 reactions have been affecting the elderly population. It states that hepatic phase 1 reaction involving oxidation, hydrolysis, and reduction appears to be more altered by age since the elderly population comprises the fastest-growing segment of the world�s population. It also states that there is a predictable, age-related decline in cytochrome P-540 function and combined with the polypharmacy that much of the elderly population experiences, this may lead to a toxic reaction of medication.

Phase 2 Reaction

Phase 2 reaction is part of the cellular biotransformation machinery and is a conjugation reaction in the body. They can involve the transfer of a number of hydrophilic compounds to enhanced the metabolites, and the excretion in the bile or urine in the body. The enzymes in Phase 2 reaction can also comprise multiple proteins and subfamilies to play an essential role in eliminating the biotransformed toxins and metabolizing steroid hormones and bilirubin in the body.

Phase 2 enzymes can function not only in the liver but also in other tissues like the small intestines. When it combined with Phase 1, they can help the body naturally detox the toxins that the body may encounter. Hormones, toxins, and drugs undergo a hepatic transformation by Phase 1 and Phase 2 pathways in the liver, then are eliminated by phase 3 pathways.

Xenobiotics

Xenobiotics has been defined as chemicals that undergo metabolism and detoxication to produce numerous metabolites, some of which have the potential to cause unintended effects such as toxicity. They can also block the action of enzymes or receptors used for endogenous metabolism and produce liver damage to a person. Xenobiotics like drugs, chemotherapy, food additives, and environmental pollutants can generate serval free radicals that lead to an increase of oxidative stress in the cells. Accumulation of oxidative stress in the body can lead to an increase in potential cellular reduction in the body.

Research shows that the body has a major challenge when it is detoxifying xenobiotics out of the body system and the body must be able to remove the almost-limitless number of the xenobiotic compounds from the complex mixture of chemicals that are involved in normal metabolism.

Studies even show that if the body doesn�t have a normal metabolism, many xenobiotics would reach toxic concentrations. It can even reach the respiratory tract either through airborne toxins or the bloodstream. It is important to make sure that the body and especially the liver to be healthy. Since the liver is the largest internal organ, it is responsible for detoxifying the toxins out of the body as urine, bile, and sweat.

Conclusion

Biotransformation is the process of substance changes from one chemical to another. In the body, it is a process of rendering fat-soluble compounds to water-soluble compounds, so it can be excreted out of the body as either urine, feces, or sweat. The liver is the one that causes toxic xenobiotics to transform into biotransformation and going through phase 1 and 2 to excrete the toxins out of the body for a healthy function.

Phase 1 reactions in the body are the first line of defense of the body detoxifying itself. Phase 2 creates CYP450 (cytochrome P450) that helps the body take the xenobiotic toxins and oxidates to reduce and hydrolysis the toxins to metabolites. Those metabolites then transform into Phase 2 reactions, which conjugates the metabolites in the body to be excreted out of the body. There are many factors that can make the body have xenobiotics, but the liver is the main organ to detoxify the xenobiotics out of the system. If there is an abundance of xenobiotics in the body, it can cause toxicity reaction causing the body to develop chronic illnesses. These products are known to help support the intestines and liver detoxication as well as, to help support hepatic detoxication for optimal healthy body function.

October is Chiropractic Health Month. To learn more about it, check out Governor Abbott�s bill on our website to get full details.

The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal and nervous health issues as well as functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions. We use functional health protocols to treat injuries or chronic disorders of the musculoskeletal system. To further discuss the subject matter above, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

References:

Chang, Jyh-Lurn, et al. �UGT1A1 Polymorphism Is Associated with Serum Bilirubin Concentrations in a Randomized, Controlled, Fruit and Vegetable Feeding Trial.� The Journal of Nutrition, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Apr. 2007, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17374650/.

Croom, Edward. �Metabolism of Xenobiotics of Human Environments.� Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2012, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22974737.

Hindawi, Unknown. �Xenobiotics, Oxidative Stress, and Antioxidants.� Xenobiotics, Oxidative Stress, and Antioxidants, 17 Nov. 2017, www.hindawi.com/journals/omcl/si/346976/cfp/.

Hodges, Romilly E, and Deanna M Minich. �Modulation of Metabolic Detoxification Pathways Using Foods and Food-Derived Components: A Scientific Review with Clinical Application.� Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism, Hindawi Publishing Corporation, 2015, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4488002/.

Kaye, Alan D, et al. �Pain Management in the Elderly Population: a Review.� The Ochsner Journal, The Academic Division of Ochsner Clinic Foundation, 2010, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3096211/.

M.Haschek, Wanda, et al. �Respiratory System.� ScienceDirect, Academic Press, 17 Dec. 2009, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780123704696000064.

panelEdwardCroom, Author links open overlay, et al. �Metabolism of Xenobiotics of Human Environments.� ScienceDirect, Academic Press, 11 Sept. 2012, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780124158139000039.

Sodano, Wayne, and Ron Grisanti. �The Physiology and Biochemistry of Biotransformation/Detoxification.� Functional Medicine University, 2010.

Unknown, Unknown. �ToxTutor – Introduction to Biotransformation.� U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, 2017, toxtutor.nlm.nih.gov/12-001.html.

Zhang, Yuesheng. �Phase II Enzymes.� SpringerLink, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 1 Jan. 1970, link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007%2F978-3-642-16483-5_4510.

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Functional Medicine, Gut and Intestinal Health, Health, Wellness

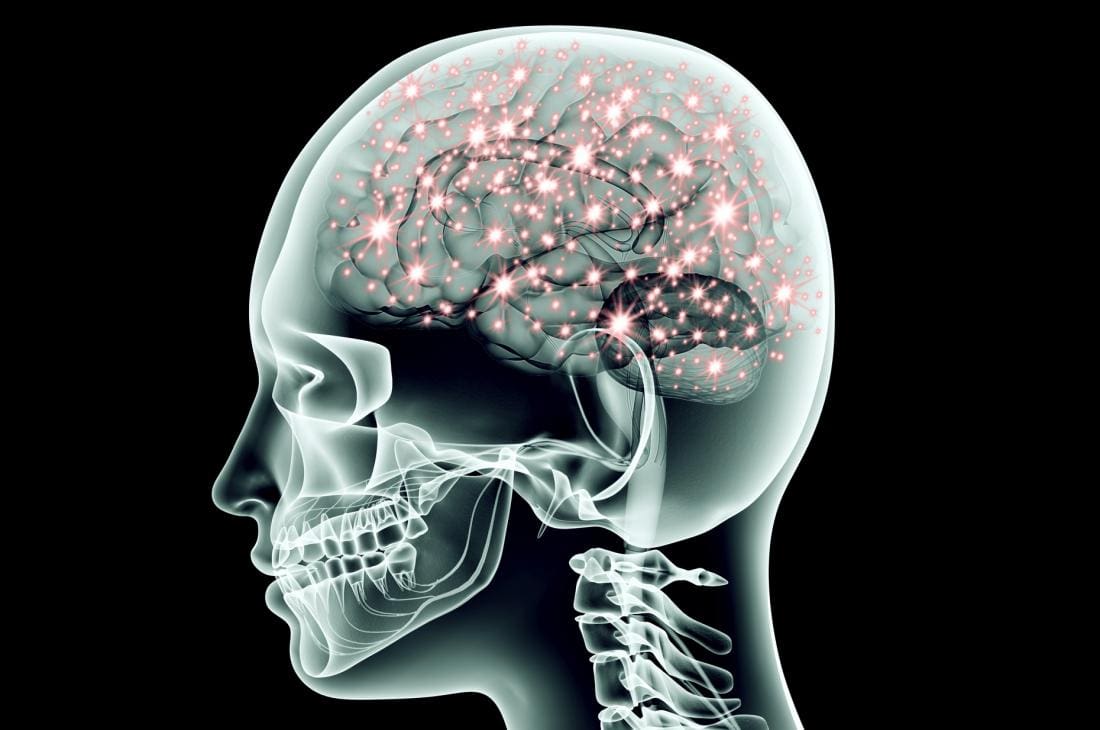

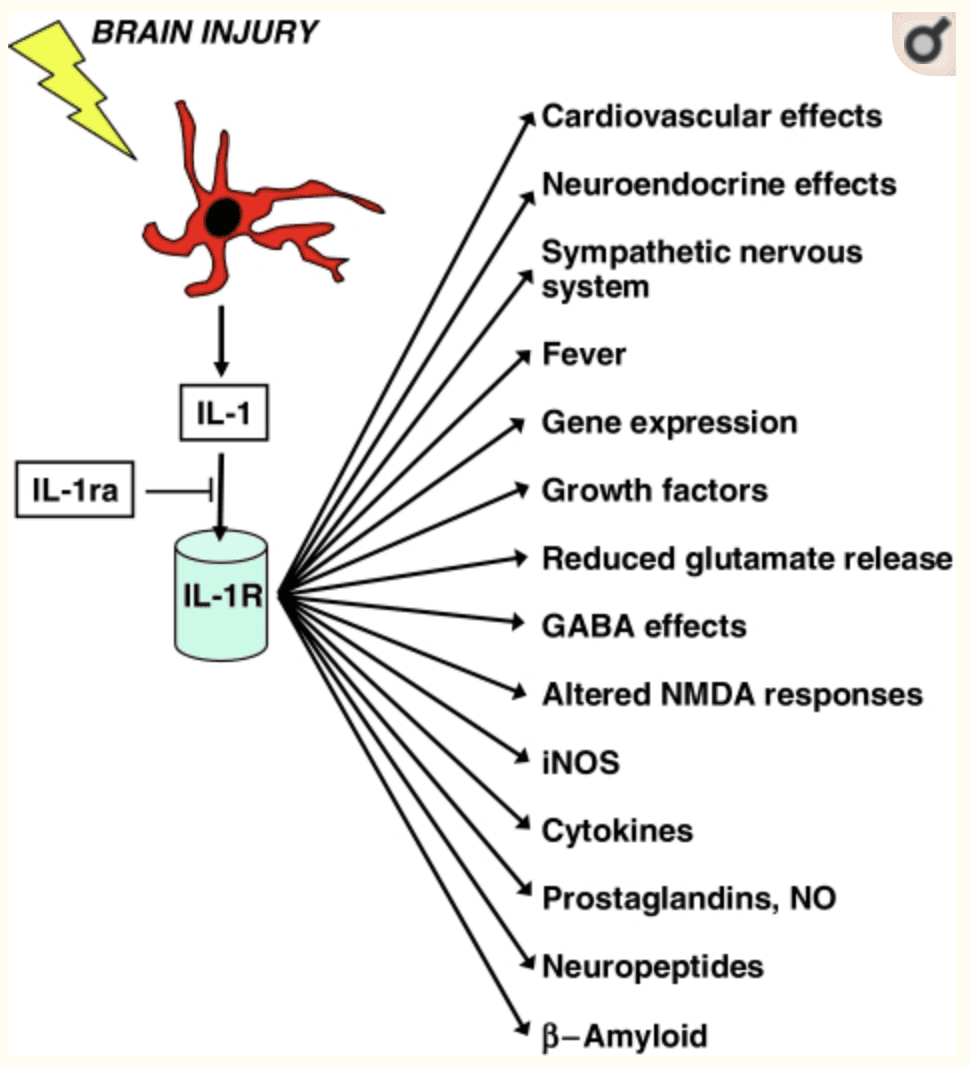

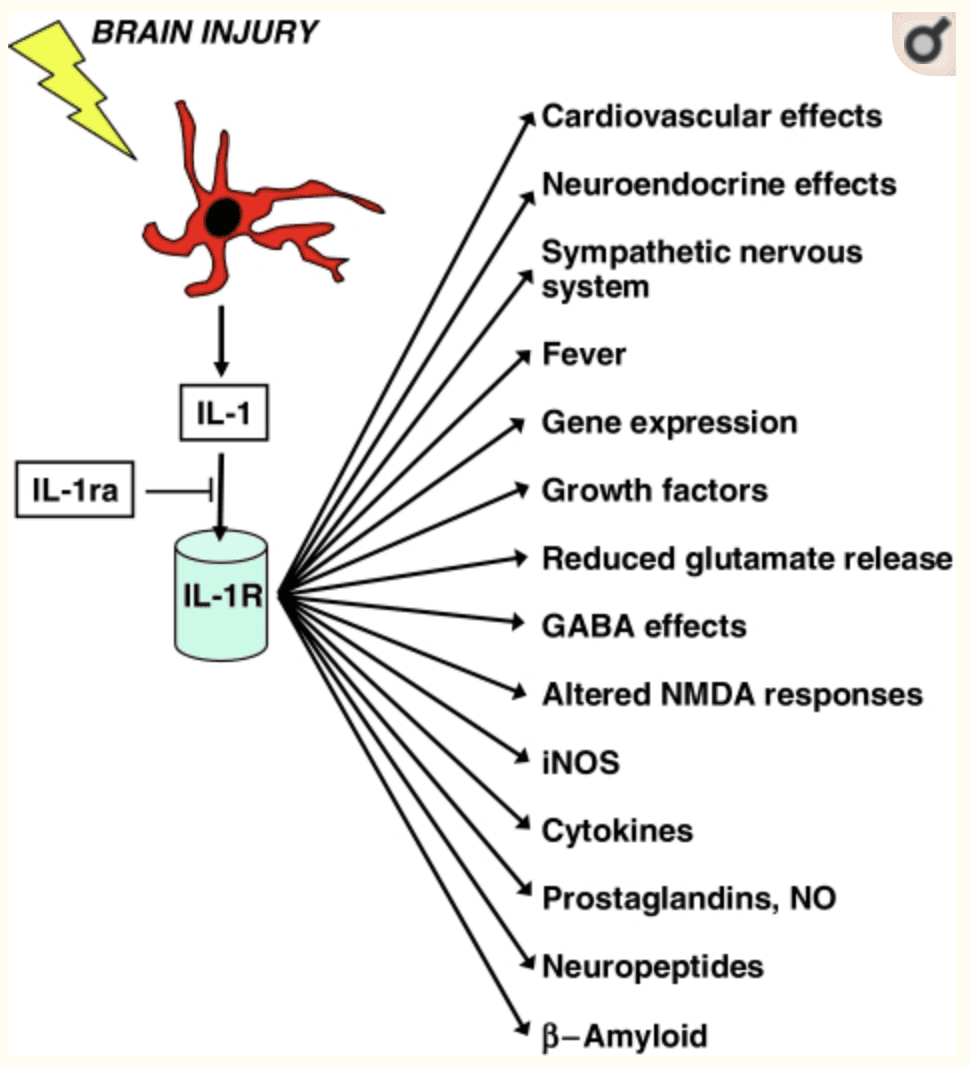

The gut-brain connection is essential in the body. If an individual has a leaky gut that is causing inflammation, it can send the signal to the brain and it can create problems like neurotransmitter dysfunction to systems that just don�t connect. The leaky gut can lead to brain dysfunction or brain dysfunction can lead to leaky gut. Sometimes an autoimmunity disease in the stomach can lead to a disruption in the mind. Then, brain disruption can also lead to inflammation in the gut. It�s a never-ending loop that the brain and gut can go on forever. Studies have stated that gut microbiota appears to influence the development of emotional behaviors like stress, pain modulation systems, and brain neurotransmitter systems.

The Brain System to the Gut System

The brain is the main control room that controls the body�s system and how the body should behave. The human brain also contains neuron cells that are found in the central nervous system. With the gut-brain connection, two critical systems help send the signal to the brain and the gut; these are known as the vagus nerve and the neurotransmitters.

The Vagus Nerve

There are approximately 100 billion neurons in the brain, while the gut contains about 500 million neurons, which is connected to the brain through the nerves in the nervous system. The vagus nerve is one of the most significant nerves that send signals back and forth to the brain and the gut. When the body is stressed, the stress signal inhibits the vagus nerve, and it can cause problems to the gut-brain connection. Animal studies have shown that any stress that is in the animal�s body can cause gastrointestinal issues and PTSD. While another study stated that individuals that have IBS (irritable bowel syndrome) have a reduced function of the vagus nerve.

There are ways to reduce the stress hormone so that the vagus nerve can function properly and send the right signals to the gut and the brain. Probiotic foods can help lower the amount of stress hormone in the bloodstream. When that happens, the body can start healing naturally when the stress is reduced; however, if the vagus nerve is damaged, then the probiotic has no effect.

Neurotransmitters

Neurotransmitters are produced chemically in the brain by controlling feelings and emotions in the body. Since the brain and gut are connected to neurotransmitters, the neurotransmitters can create these compounds that help contribute to the body. In the brain, the neurotransmitter can produce serotonin to make the person feel happy and help control their body�s biological clock.

In the gut, there are trillions of microbes that live there, and interestingly researchers stated that serotonin is mainly being produced by the gut system. Another neurotransmitter that is provided in the gut is called GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid), which helps control the feeling of fear and anxiety. When the brain feels overly anxious or has been through a traumatic experience that has caused them to be fearful, it can cause them to be hypersensitive and can cause a chemical imbalance to the gut, causing inflammation or leaky gut if it is severe.

The Gut System to the Brain System

The gut microbes can produce neurotransmitters to send to the brain, protect the intestinal barrier and the tight junction integrity, regulate the mucosal immune system, and modulates the enteric sensory afferents. The gut microbe produces a lot of SCFA (short-chain fatty acids) that form a barrier between the brain and blood flow called the blood-brain barrier. The blood-brain barrier protects the CNS (central nervous system) from toxins, pathogens, inflammation, injury, and disease.

The gut microbes also metabolize bile and amino acids to help produce other chemicals that affect the brain. When the body is stressed, it can reduce the production of bile acid by gut bacteria and alter the genes that are involved. When that stress is still creating problems in mind, the gut can develop gastrointestinal issues that will destroy the permeability barrier that is protecting the intestines.

The gut-brain connection plays an essential role in the body�s immune system as it controls inflammation and what passes into the body. Since the immune system controls inflammation, if it is turned on for too long, inflammation can occur as well as several brain disorders like depression and Alzheimer�s disease. Stress can even disrupt the gut by causing contractions to the GI tract, make inflammation worse in the intestinal permeability, and making the body more at risk to infections.

When the body starts to alleviate stress, it can naturally heal itself, and the gut-brain connection can begin functioning normally. With changes in a person�s eating habits and lifestyle, it can drastically change a person�s mood and recover from intestinal ailments they may have. If the brain feels right, then the gut feels good as well. They work together side by side to make sure that the body is functioning correctly. When either one is being disrupted, then the body does not function properly.

Conclusion

Therefore, the gut-brain connection is vital to the body. Neurotransmitters and other components that are in both systems work together to make sure that the body is working correctly. When one of the connections is being disrupted, however, the body can develop many chronic illnesses even if the person seems fine. By altering little things like changing a person�s diet and lifestyle, it can help improve the body and bring the balance back to the gut-brain connection.

In honor of Governor Abbott’s proclamation, October is Chiropractic Health Month. To learn more about the proposal on our website.

The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal, and nervous health issues as well as functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions. We use functional health protocols to treat injuries or chronic disorders of the musculoskeletal system. To further discuss the subject matter above, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

References:

Anguelova, M, et al. �A Systematic Review of Association Studies Investigating Genes Coding for Serotonin Receptors and the Serotonin Transporter: I. Affective Disorders.� Molecular Psychiatry, U.S. National Library of Medicine, June 2003, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12851635.

Bravo, Javier A, et al. �Ingestion of Lactobacillus Strain Regulates Emotional Behavior and Central GABA Receptor Expression in a Mouse via the Vagus Nerve.� Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, National Academy of Sciences, 20 Sept. 2011, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21876150.

Carabotti, Marilia, et al. �The Gut-Brain Axis: Interactions between Enteric Microbiota, Central and Enteric Nervous Systems.� Annals of Gastroenterology, Hellenic Society of Gastroenterology, 2015, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4367209/.

Daneman, Richard, and Alexandre Prat. �The Blood-Brain Barrier.� Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 5 Jan. 2015, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4292164/.

Herculano-Houzel, Suzana. �The Human Brain in Numbers: a Linearly Scaled-up Primate Brain.� Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, Frontiers Research Foundation, 9 Nov. 2009, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2776484/.

Lucas, Sian-Marie, et al. �The Role of Inflammation in CNS Injury and Disease.� British Journal of Pharmacology, Nature Publishing Group, Jan. 2006, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1760754/.

Mayer, Emeran A, et al. �Gut/Brain Axis and the Microbiota.� The Journal of Clinical Investigation, American Society for Clinical Investigation, 2 Mar. 2015, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4362231/.

Mayer, Emeran A. �Gut Feelings: the Emerging Biology of Gut-Brain Communication.� Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 13 July 2011, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3845678/.

Mazzoli, Roberto, and Enrica Pessione. �The Neuro-Endocrinological Role of Microbial Glutamate and GABA Signaling.� Frontiers in Microbiology, Frontiers Media S.A., 30 Nov. 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5127831/.

Pellissier, Sonia, et al. �Relationship between Vagal Tone, Cortisol, TNF-Alpha, Epinephrine and Negative Affects in Crohn’s Disease and Irritable Bowel Syndrome.� PloS One, Public Library of Science, 10 Sept. 2014, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25207649.

Rooks, Michelle G, and Wendy S Garrett. �Gut Microbiota, Metabolites and Host Immunity.� Nature Reviews. Immunology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 27 May 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27231050.

Sahar, T, et al. �Vagal Modulation of Responses to Mental Challenge in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder.� Biological Psychiatry, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 1 Apr. 2001, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11297721.

Yano, Jessica M, et al. �Indigenous Bacteria from the Gut Microbiota Regulate Host Serotonin Biosynthesis.� Cell, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 9 Apr. 2015, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4393509/.

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Functional Medicine, Gut and Intestinal Health, Health, Wellness

SIBO (small intestinal bacterial overgrowth) is defined as 105 up to 106 organisms of bacteria in the small intestines. It is highly relevant to remember that the abundance of bacteria in the small intestine that has SIBO, are healthy bacteria that live in the gastrointestinal tract. It means that the bacteria in the digestive tract is either missed or dislocated and is in the wrong place in the small intestines. While SIBO still remains a poorly understood disease, it is frequently implicated to be the cause of chronic diarrhea and malabsorption. Individuals who have SIBO can also suffer from many chronic illnesses. This includes unintended weight loss, nutritional deficiencies, and osteoporosis.

SIBO and IBS

Studies have indicated that 84% of individuals that has IBS (irritable bowel syndrome) will have SIBO. SIBO is one of the causes of leaky gut, and leaky gut is one of the triad factors that can lead the body to have an autoimmune disease. Health care professionals that diagnose individuals who have SIBO can link the virus to other health problems that the individual may have. Studies have mentioned that when LPS (lipopolysaccharide) is moving from the large intestines to the small intestines, it can contribute to developing intestinal inflammation. With LPS, it can cause an increase of intestinal tight junction permeability or leaky gut.

So SIBO will release LPS into the gut, causing the leaky gut to the gut system in the body. Another study showed that autoimmune diseases are always a triad of a few different things. To have an autoimmune disease, you have to have the gene to get the disease. Although most people know that if they have a gene, doesn�t mean that they will have an autoimmune disease. Even if they don�t have an autoimmune disease, there�s an environmental trigger that will come on and creates an epigenetic change. This will cause the gene in the human body to be expressed.

So the first two factors of the autoimmune disease, are a genetic factor and an environmental factor, the third and final factor is intestinal permeability. So if the primary two factors that are causing disruption to the intestinal permeability, they will prevent the intestinal permeability to actually heal itself. With all three elements being linked to autoimmune disease and SIBO, it will cause the body to have the leaky gut syndrome and health problems to individuals.

So when doctors are diagnosing the patient that has SIBO, they will do a lactulose breath test. What this test does, is that it will indicate that the patient has IBS bloating, and it is causing them discomfort in their gut. Research stated that the lactulose breath test shows the correlation between the pattern of the bowel movements and the type of excreted gas in the stomach. So for anyone that is positive with IBS and takes the breath test, they will understand the consequences of the factors that are leading to the SIBO disease and causing leaky gut.

How do we get SIBO?

With the understanding of what SIBO is, we can see that SIBO is not the only cause of irritable bowel syndrome, but the big player of the syndrome. So taking a step back, we have to discuss what the MMG (Migrating Motor Complex) is before we go further in explaining the pathogenesis of the SIBO disease. Migrating motor complexes are waves of electrical activity that is sweeping through the intestines in a regular cycle. It often happens when a person is fasting, therefore with MMG, we can look at the acute gastroenteritis in the body.

With acute gastroenteritis, the body has some sort of severe infection like bloating, diarrhea, constipation, or a variety of things that are infectious to the gut; however, they are self-limiting. Healthcare professionals who see patients with these acute infections can see that most of the bacteria can cause gastroenteritis, pile up, and release CTD (cytolethal distending toxin). What CTD does is that it will create a reaction against vinculin; which regulates the ICC (interstitial cells of Cajal) and the ICC then regulates the migrating motor complex.

So when the CTD releases toxins in the gut, it causes a reaction to a molecular mimicry reaction. That reaction causes the body to create antibodies to fight against that toxin but through molecular mimicry. CTD looks exactly like vinculin and cross-reacts with the antibodies, So now those antibodies are attacking vinculin, thus damaging the ICC. Since the MMC clears the intestinal tract, when a person is fasting, and the CTD is damaging the intestines, SIBO is created since the body can not flush out the bacteria.

Studies have shown that there are many ways to get SIBO, it can happen by either food poisoning, abdominal surgery, or low stomach acid. Another thing to mention is that mostly 70% of SIBO is caused by food poisoning. Most people who had to suffer from food poisoning don�t realize that SIBO is already in their gut. So the research states that small bowel motility disorders can be the predispose development of SIBO since the bacteria may not be effectively swept from the bowel into to colon.

Treating SIBO

There are many ways to treat SIBO, healthcare professionals can suggest these treatments to their patients who have SIBO and start restoring their intestinal barrier in the long haul. So here are some of the procedures that can help the body and treat SIBO.

- Pharmaceuticals: If a patient has constipation and is taking rifaximin if the symptoms are not clearing up, adding another medication with rifaximin for 14 days may help in battling SIBO. It will take a bit longer, but it will help clear the SIBO out of the gut.

- Herbal Treatment: With herbal treatments, there are many ways to help treat SIBO naturally. It can be berberine containing herbs, oil of oregano, neem, garlic, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lauricidin, and Antrantil. These herbal treatments can naturally help to fight against SIBO, and studies show that 46% of patients feel a lot better in a short amount of time.

Conclusion

So SIBO is a bacterial disease that can disrupt the gastrointestinal tract and cause the leaky gut to the body. It will cause inflammation and can be in an individual�s body through three factors like genetics, environmental triggers, and food poisoning. It can be treated through pharmaceuticals and herbal treatments prescribed by doctors.� In honor of Governor Abbott’s proclamation, October is Chiropractic Health Month, learn more about this proposal on our website and read what the proposal is all about. The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal, and nervous health issues as well as functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions. We use functional health protocols to treat injuries or chronic disorders of the musculoskeletal system. To further discuss the subject matter above, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

References:

Bezine, Elisabeth, et al. �The Cytolethal Distending Toxin Effects on Mammalian Cells: a DNA Damage Perspective.� Cells, MDPI, 11 June 2014, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4092857/.

Brown, Kenneth, et al. �Response of Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Constipation Patients Administered a Combined Quebracho/Conker Tree/M. Balsamea Willd Extract.� World Journal of Gastrointestinal Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Baishideng Publishing Group Inc, 6 Aug. 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4986399/.

Chedid, Victor, et al. �Herbal Therapy Is Equivalent to Rifaximin for the Treatment of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth.� Global Advances in Health and Medicine, Global Advances in Health and Medicine, May 2014, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4030608/.

Dukowicz, Andrew C, et al. �Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: a Comprehensive Review.� Gastroenterology & Hepatology, Millennium Medical Publishing, Feb. 2007, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3099351/.

Endo, EH, and Dias Filho. �Antibacterial Activity of Berberine against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Planktonic and Biofilm Cells.� Austin Journal of Tropical Medicine & Hygiene, 19 Feb. 2015, austinpublishinggroup.com/tropical-medicine/fulltext/ajtmh-v1-id1005.php.

Fasano, Alessio, and Terez Shea-Donohue. �Mechanisms of Disease: the Role of Intestinal Barrier Function in the Pathogenesis of Gastrointestinal Autoimmune Diseases.� Nature News, Nature Publishing Group, 1 Sept. 2005, www.nature.com/articles/ncpgasthep0259.

Ghonmode, Wasudeo Namdeo, et al. �Comparison of the Antibacterial Efficiency of Neem Leaf Extracts, Grape Seed Extracts and 3% Sodium Hypochlorite against E. Feacalis – An in Vitro Study.� Journal of International Oral Health: JIOH, International Society of Preventive and Community Dentistry, Dec. 2013, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24453446.

Guo, Shuhong, et al. �Lipopolysaccharide Regulation of Intestinal Tight Junction Permeability Is Mediated by TLR4 Signal Transduction Pathway Activation of FAK and MyD88.� Journal of Immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950), U.S. National Library of Medicine, 15 Nov. 2015, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26466961.

Lin, Henry C. �Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: a Framework for Understanding Irritable Bowel Syndrome.� JAMA, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 18 Aug. 2004, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15316000.

Preuss, Harry G, et al. �Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations of Herbal Essential Oils and Monolaurin for Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria.� Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Apr. 2005, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16010969.

Sienkiewicz, Monika, et al. �The Antibacterial Activity of Oregano Essential Oil (Origanum Heracleoticum L.) against Clinical Strains of Escherichia Coli and Pseudomonas Aeruginosa.� Medycyna Doswiadczalna i Mikrobiologia, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2012, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23484421.

Soifer, Luis Oscar, et al. �Comparative Clinical Efficacy of a Probiotic vs. an Antibiotic in the Treatment of Patients with Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth and Chronic Abdominal Functional Distension: a Pilot Study.� Acta Gastroenterologica Latinoamericana, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Dec. 2010, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21381407/.

by Dr Alex Jimenez DC, APRN, FNP-BC, CFMP, IFMCP | Functional Medicine, Gastro Intestinal Health, Gut and Intestinal Health, Health

For anyone that has dealt with mold knows that it is mostly found in fresh produce when it hasn’t been eaten. It is even there is a new damp spot in the house, and it�s left untreated. Mold is a type of fungus that is presented everywhere, including the air. It can actually cause someone highly sensitive to mold exposure to have chronic raspatory illnesses like asthma and bronchitis.

Studies show that the most common species of mold is Stachybotrys chartarum or black mold. This type of fungus thrives in warm, moist environments, including the basement, the bathroom, and the kitchen. It releases toxins in the air that is irritating or harmful to individuals with existing health conditions and becoming mycotoxin.

What is Mycotoxin?

A mycotoxin is a secondary metabolite being produced by organisms of the fungal kingdom. It can move in and out of cells in the body, causing inflammation when it is indigested. Researchers suggest that mycotoxin can link to serious health problems to people who live in contaminated buildings, and it can have long-term results. In most cases, mycotoxin can cause problems in the gut by consuming moldy food; causing leaky gut and destroying the gut microflora.

Here are some of the symptoms of mycotoxin:

- Aches and pains

- Mood changes

- Headaches

- Brain fog

- Asthma

- Watery, red eyes

- Runny or blocked nose

- Gut inflammation

- Sore throat

They are teratogenic, mutagenic, nephrotoxic, immunosuppressive, and carcinogenic. They can cause DNA damage, cancer, immune suppression, neurological issues, and a variety of adverse health effects on the human body. With mycotoxins, they have spores and pieces of hyphae that releases toxins into the air. They are tiny, but they are not easily detectable in the bloodstream since they can attach themselves to enzymes that are involved in insulin receptors. This results in dysfunction the in cells ability to intake and process glucose in the gut.

When mycotoxin is in the gut, it damages the intestinal barrier. It can cause malabsorption of food and disrupts the protein synthesis. When that happens, the individual�s autoimmunity will rise up, causing their bodies to go into overdrive to fight the problem.

Mycotoxin can actually grow in grains such as rice. The fungal mycotoxin has been known to cause liver damage since the contaminated food is being consumed by people, and it creates a rise in inflammation. When this happens, individuals start being sensitive to the contaminated foods that they are consuming. There is still more research to mycotoxin that is being produced to create a resistance to mycotoxin exposure.

Diagnosing Mycotoxin

Mycotoxin can�t be diagnosed by the symptoms themselves, doctors can perform one of these tests to determine the severity of mycotoxins in individuals.

- Blood test: Physicians can take a patient�s blood sample and send it to a testing lab to test. This is to see if there is a reaction of specific antibodies in the patient�s immune system. A blood test can even check the individual�s biotoxins in their blood to see if mycotoxin present.

- Skin prick test: Healthcare professionals can take tiny amounts of mold and use a small needle to apply it onto the patient�s skin. This is to determine if the individual is breaking out in bumps, a rash or hives, then they are allergic to any mold species.

Diagnosing mycotoxin is known by many names, but it is mostly called mast cell disorder. Even though they are different and have different manifestations, diagnosing them in the body is essential to help individuals to heal their ailments. With technology getting better, healthcare physicians can detect mycotoxins in the body much faster.

Treating Mycotoxin

There are many ways to treat mycotoxin. Options include:

- Avoiding the mold whenever possible.

- A nasal rinse to flush out the mold spores that are in the nose.

- Antihistamines to stop the itchiness, runny noses, and sneezing due to mold exposure.

- A short term remedy for congestion is using decongestant nasal spray.

- Montelukast is an oral medication to reduce the mucus in a patent�s airways to lower the symptoms for both mold allergies and asthma.

- Doctors can recommend patients an allergy shot to build up the patient�s immunity to mycotoxin if the exposure is long term.

How to check for mycotoxin?

When individuals are checking for mycotoxins in their environment, it is best to hire professionals to help identify and remove it. A lot of individuals can look for black clusters growing in warm, moist rooms and can search for the causes of mold growth like any leaks, old food, papers, or wood. People can throw away the items that are affected by mold or that are contributing to mold growth. They can also remove the things that are not affected by mold exposure.

Wearing a mold-resistant suit, mask, gloves, and boots can protect individuals as they are getting rid of mildew and mold from their environment. Even purchasing a HEPA air purifier can help get rid of the spores to ensure that no allergens will affect the body�s immune system. When individuals are removing the mold exposure out of the affected area, they can cover the non-affected surfaces with bleach or a fungicidal agent. Then let it dry to prevent the mold from reproducing on the same area it has infected.

Conclusion

Since researchers are still doing a test on mycotoxin, mold exposure is still all around the world and in many forms. It can even contaminate food and places where it can thrive and grow. Individuals can prevent it from locating the source and can take precautions when they are exposed to the spores. If the individual is exposed to mycotoxin, going to the doctors to get tested is the best route to go. The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal, and nervous health issues as well as functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions. We use functional health protocols to treat injuries or chronic disorders of the musculoskeletal system. To further discuss the subject matter above, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

References

Borchers, Andrea T, et al. �Mold and Human Health: a Reality Check.� Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, June 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28299723.

Do�en, Ina, et al. �Stachybotrys Mycotoxins: from Culture Extracts to Dust Samples.� Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Aug. 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4939167/.

Gautier, C, et al. �Non-Allergenic Impact of Indoor Mold Exposure.� Revue Des Maladies Respiratoires, U.S. National Library of Medicine, June 2018, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29983225.

Hurra�, Julia, et al. �Medical Diagnostics for Indoor Mold Exposure.� International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Apr. 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27986496.

Jewell, Tim. �Black Mold Spores and More.� Black Mold Exposure, 1 June, 2018, www.healthline.com/health/black-mold-exposure.

Leonard, Jayne. �Black Mold Exposure: Symptoms, Treatment, and Prevention.� Medical News Today, MediLexicon International, 17 Sept. 2019, www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/323419.php.

Pitt, John I, and J David Miller. �A Concise History of Mycotoxin Research.� Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 23 Aug. 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27960261.

Sun, Xiang Dong, et al. �Mycotoxin Contamination of Rice in China.� Journal of Food Science, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Mar. 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28135406.